Miller's Marine War Risks Textbook

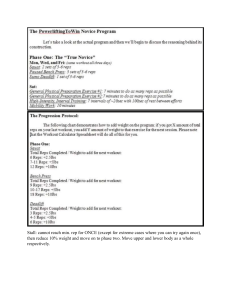

advertisement