Export/Import Procedures & Documentation: 4th Edition

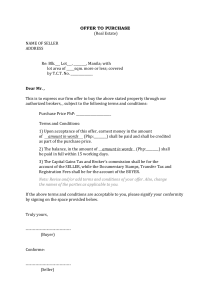

advertisement