Critical Thinking & Problem-Solving: Educator's Voice Journal

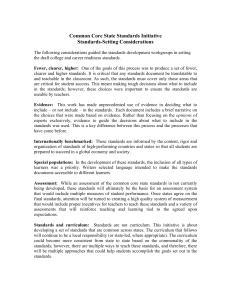

advertisement