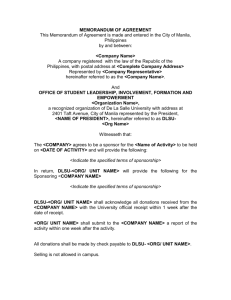

College |KelMion

HISTORY OF THE

REPUBLIC OF THE

PHILIPPINES

—

~ HISTORY OF THE

REPUBLIC OF THE

PHILIPPINES

Revised Edition

Gregorio F. Zaide

Sonia M. Zaide

|

BOOK STORE, IRC.

PUBLISHERS e METRO MANILA

PHILIPPINES

Published by National Book Store, Inc.

COPYRIGHT, 1983, 1987 by

GregorioF. Zaide & —

Sonia M. Zaide

Revised Edition

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be

reproduced in any form or by

any means, except brief quotations

for a review, without permission

in writing from the Authors.

PCPM

Certificate of

Registration No. SP 594

Cover Design by

Ed Abad

Printed by

Cacho Hermanos,

Inc.

Corner Pines & Union Sts.

Mandaluyong, Metro Manila

ISBN 971-08-3995-0

—

“In order to read the destiny of a people, it is necessary

to open the book of its past.”

—

Dr. Jose Rizal

CONTENTS

DR

Bei

1

2

as

es ey

ade es

soi

ene sus oe

a

ee

Geographical Foundations of

PUD

PAIBIOI eon

he a

wes

de

at

: The Philippines as a Unique

INOUE AN Ue WOM 9S, on ie csicacasse

Say iy end.

3

The Dawn of Philippine History

.-:.................

4

Asian Heritage of the Filipinos.

....................

5

The Rediscovery of the Philippines

...... bw es

6

The Conquest by Cross and Sword

...............

: 7

8

The Spanish Colonial Seetem

sme

oiey ides

Spain’s Dream in Asia of Empire

.................

|

9

be,

Relations with the Chinese and

?

PADAIIOSC Sie alc Se wh Sh GSMs vg

7 10

Philippine-Mexican Relations

RA

12

13

14

Vii

.......................

~ 108

ihe Moto Wats

‘British Invasion of the PRUIDDINES

oo

Filipino Revolts Against Spanish Rule

epee

131

...........

140

Economic Development Under SPAIN | 5c ces.s25

15 Hispanic Heritage of the Filipinos ................

16 = The Twilight of Spain’s Rule ........ccccescseee.

17. The Birth of Philippine Nationalism ...........:..

Propaganda Movement and the

Katipunan .......... gOS ae

Coes

_ The Philippine Revolution

eae

166

178

196

- 207

ee ecereseseesecorersesens

215

eoresbosecvsseserssorsos

229

The Coming of the United States and

the End of Spanish Rule

eo

ee

iy

252

“h

21

Rise and Fall of the First

|

Phitippine: Reoubhit (coon

is cee

22

America’s Rule and Democratization

of the: Filipino People

oo... ocajsennssc: ane eaeses

23 > Economic Progress Under the

* United States « ...2.<.... Se

ee

24

...............

.........................

340

ae seraracee

........... sSiee

25

The Commonwealth of the Philippines

26

The Philippines and World War II

ZY

apanese Occupation and the

Second Philippine Republic

..........

Independence and the Third

Philippine Republic

........... Ngo

Martial Law and the New

30

Birthof the New Philippine

Republics re crsc cicty a toeensk ace icone aren eee

NOTES

360

378

aap RSS era as eR

29

31

Society.

................

caaee

Downfall of Marcos Dictatorship and

Restoration of Democracy Under

PresidéntsA@uine un. eer

ee ie

..... Renee eee ct

271

291

302

314

326

eee

= American Heritage of the Filipinos

28

261

Bee

a

401

408

OAs a

eee

ad

aa

461

PREFACE

This book is especially written to fill the need for a textbook

on Philippine history in our universities and colleges, particularly

for the mandated three-unit course which is rorutred of all

college students.

It is our sincere belief that a Philippine history textbook

for college must be comprehensive, well-balanced, written in a

humanized style, and, above all, richly documented.

Comprehensive, in the sense that it must give a full account

of the nation from the barangay era to the present period. Ours

indeed is an epic of a spirited, intelligent, friendly and resilient

people who have endured centuries of different cultural experiences, and yet prevailed to achieve a unique identity as a nation.

Well-balanced, in the sense that a history survey must narrate

the people’s political, economic,

socio-cultural,

religious, and

scientific development. History is like a glistening prism of many

facets, a picturesque tapestry of many threads and colors, a

chronology of dates, events and personalities over a period of

time. This process can be subject to different interpretations,

but overall such developments must yield to the facts on the

struggles, ideals, and achievements of people.

Humanized style, in the sense that history must be portrayed

in a fascinating manner and in a language that makes it interesting

to read.

Richly documented, in the sense that history is best written

based on reliable primary and secondary sources. Documentation

is the life-blood of reliable historiography. As Dr. Jose Rizal

noted in a letter to Professor Blumentritt on April 17, 1890,

‘The majority of historians of the Philippines are mere copyists.”’

One must have an authoritative grasp of the sources on a subject

before one can write a good history of any subject.

The senior author of this book devoted his life’s work to

research not only in the Philippines, but also in foreign countries

—

archives in Spain, Portugal, Britain, the Vatican, Mexico,

the United States, etc. — where he broadened his perspective

vii

on Philippine history. Both the authors of this book have spent

many years of academic

Philippine history.

woyk in the teaching and study of

In writing this book, the authors owe a debt of

to the directors and staffs of various archives both

abroad — in particular, that of the Archivo General

(Seville), Biblioteca Nacional (Madrid), Nacional de

gratitude

here and

de Indias

Torre do

Tombo (Lisbon), the Public Record Office (London and Kew,

Surrey), the British Museum (London), the India Office (London), the Biblioteque Nationale (Paris), the Vatican Library and

Archives (Italy), the Library of Congress (Washington, D.C.),

the New York Public Record Office, the Boston Public Library,

and the Archivo General de la Nacion (Mexico City).

The senior author owed special thanks to his friend and

colleague, Professor Esteban de Ocampo, for letting him read

valuable Filipiniana materials in his private library.

We hope that the readers of this book may

appreciate the country and its historical heritage,

uniquely Asian, European, Latin, and American.

Gregorio F. Zaide

Sonia M. Zaide

Manila, June 30, 1983.

come to

which is

—

Postscript

Since this preface was written, the senior author passed away last

31 October 1986. Thanks to his notes and completed typescripts for

other books, including a twelve-volume documentary history of the

Philippines, I have been able to revise and update this book for its

second edition.

Previous users of this book, and students coming from secondary

schools, will notice that there have been many changes. Among the

most noteworthy changes are:

(1) Deletion of the historical notes from the Maragtas and Kalantiaw Code, since both spree to be 20th century creations (Chapters

3 and 4);

(2) Inclusion of the challenge to the migration theory by contemporary. scholars (Chapter 3);

(3) Recognition of Francisco Serrano as the first European to

visit the Philippines in 1512 (Chapter 5);

(4) Correction of the location of the first mass in the Philippines,

which was celebrated on March 31, 1521, in Masao, Butuan, Agusan

del Norte, and not in Limasawa, Leyte, as was first commemorated

(Chapter 5);

:

(5) Brief section on the centrifugal and centripetal forces during

the Spanish era (Chapter 8);

(6) Addition of a missing chapter on Filipino revolts against

Spain (Chapter 13);

(7) Recognition that the battleship Maine, which set off the

Spanish-American War of 1898, was blown up by American spies to

provoke the declaration of war (Chapter 20);

(8) A reconsideration of the American economic policy towards .

_ the Philippines in the colonial era (Chapter 23);

(9) A reconsideration of the Marcos era, martial law and the New

Society (Chapters 28 to 31); and

=

(10) Inclusion of the “People Power Revolution” and the Aquino

provisional government until the ratification of the new Constitution

of February 2, 1987 (Chapter 31).

ix

As the Philippines enters a new era in its history, I know that my

late father would have wished us all, in this country that he loved so-

much, God speed. To the new generation of Filipino teachers and

students who will see the rise of the Philippines as the “Light of Asia”

in every way — spiritual, political and economic — this book is

dedicated.

—

:

_

4 February 1987

Pagsanjan, Laguna

Sonia M. Zaide

1

Geographical Foundations

of Philippine History

TO UNDERSTAND THE history of any country, it is

necessary to first know its geography. As the eminent American

social scientist, Dr. Harry E. Barnes, said: “It is geography

which gives individuality to nations and produces the variety of

customs and occupations, which are a product of man’s reaction

to different environments.” No wonder, Friedrich Hegel, famous

German philosopher, regarded, “‘geography as the basis of his-

tory”’.!

Philippine

.

Names

:

in Song and Story. The

present

name

“Philippines”, by which the country is known to the world, was

given by the Spanish explorer, Ruy Lopez de Villalobos, in the

year 1543 in honor of Crown Prince Philip, who later became

King Philip II of Spain (1566-1598). This name first appeared

in a rare map published in 1554 by Giovanni Ramusio (Italian

cartographer) in the second edition of his book Della Navigationi

et Viaggi (published in Venice, 1554).?

An early Recollect friar-historian, Rodrigo de Aganduru

Moriz (1584-1626), asserted that the Philippines was an ancient

country called Ophir, a country mentioned in the Old Testament

which supplied King Solomon with gold (1 Kings 9:28).° Some

early Spanish friar-historians, including Father Francisco Colin

(Jesuit) and Fray Juan Francisco de San Antonio (Franciscan),

claimed that the Philippines was the Maniolas,* a group of islands

mentioned by Claudinus Ptolemy (A.D. 90-168) in his geographical work titled Geographia.

Ages before the coming of Magellan to the country, the

early Chinese traders called the Philippines Ma-yi (Ma-i). This

name first appeared in an old Chinese historical book entitled

Wen Shiann Tun Kao (General Investigation on the Chinese

1

HISTORY OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES

Cultural Sources), written by Ma Tuan-Lin in 1317-1319.° This

Chinese name Ma-yi (originally applied, to Mindoro) was

popularized by Chau Ju-Kua, Chinese Superintendent of Foreign

Trade in Chuanchou (now Chinkiang, Fukien) in his book Chu-

fan-chi (Records of Foreign Nations), written in 1225.°

In 1521 Ferdinand Magellan accidentally reached the Philippines and named the country the “Archipelago of St. Lazarus”

(Archipielago de San Lazaro).’ Other European explorers and

writers after Magellan gave other names'to the Philippines,

such

as ‘‘Western Islands” (Islas de Poniente); “‘Eastern Islands” (Islas

del Oriente), “Archipelago of Magellan’”’ (Archipielago de Magallanes), and ‘‘Archipelago of Legazpi’’ (Archipielago de Legazpi).*

Modern authors have garlanded the Philippines with other

names, including “Gems of the East”, “Emerald Islands”, “Treasure Islands of the Pacific”, “Isles of Fear”, “Isles of Hope”,

“Orphans of the Pacific’? and “Land of the Morning”.

The most romantic name of the Philippines is “‘Pear! of the

Orient’”’.?

;

Origin of the Philippines. The origin of the Philippines is a

puzzling mystery which titillates the imagination of scholars and

scientists. According to theologians, citing the Old Testament,

the Philippines was part of God’s creation of the world.

Folklorists, on their part, recount certain legends on the genesis

of the Philippines. One of these legends runs as follows:'°

Long, long ago there was no land. There were only the

sky, the sea, and a flying bird. At that time, the sky was

hanging:so low, almost kissing the sea. For a long time, the

bird flew and flew. One day, being so tired, it desperately

looked around for a place to rest, but found no such spot.

Being a clever bird, it incited the sky and the sea to quarrel.

The sea angrily hurled big waves against the sky. To escape

being wet, the sky rose high. Higher and higher it soared,

and still the frothing sea waves reached ‘it. In retaliation, the

sky rained down many rocks which pacified the raging sea.

Out of these rocks originated the first lands, including the

Philippines.

Another

legend, equally fabulous as the one mentioned

above, chants the origin of the Philippines as follows:'!

Once upon a time there was no land. The world was

vast ball of solid rock borne by a giant on his mighty shoulders.

Geographical Foundations of Phitippine History

One day he became tired and let his heavy burden slide

down his shoulders. As it fell through space, it crashed to

pieces. Out of the shattered fragments arose the lands, including the Philippines.

Certain

geographers,

including

Baron

Adelbert

von

Chamisso, Karl Semper, and James Churchward, opine that the

Philippines is a remnant of a vast continent in the Pacific which

sank below the ocean waters during prehistoric times, like the

fabled Atlantis in the Atlantic Ocean. This lost Pacific continent

was called Lemuria or Mu. Its remnants, aside from the Philippines, are said to be Borneo, Celebes, Java, Sumatra, Carolines,

Palaus, Hawaii, Samoa, Tahiti and other islands of Oceania.

Some geologists, notably Dr. Bailey- Willis, maintained that

the Philippines was of volcanic origin'*. The eruptions of sea-volcanoes in remote epochs caused the emergence of the islands

above the seas, and in this way the Philippines was born.

The majority of scientists and scholars affirm the popular

theory that the Philippines, like Japan, Formosa,

Borneo

and

Indonesia, was once a part of Asia. During the post-glacial age,

the world’s

ice melted,

causing the level of the seas to rise;

consequently, the lower regions of the earth, including the land_bridges linking Asia and the Philippines, were submerged. Thus

the Philippines was separated from the mainland of Asia.

Location. The Philippines is a broken rosary of verdured

islands and islets floating athwart the southeastern rim of Asia.

A glance on the map shows her strategic location in the Asian

world.

By her strategic geographical location, the Pikoene: is

destined to play a significant role in global affairs. She serves

as a bridge linking the Oriental and Occidental worlds; she is

the crossroad of Asia’s air and sea routes: she looms as democracy’s bastion against the surging tides of communism in the

Asian world; and she is the lone citadel of Christianity in the

non-Christian world of the Orient.

Area. The Philippines is an archipelago of 7,100 islands (of

which 2,773 are named), with a total land area of 115,707 square

miles (299,681 square kilometers). In terms of land area, the

Philippines is almost as large as Italy (116,303 sq. miles), larger

than New Zealand (103,736 sq. miles), twice bigger than Greece

3

HISTORY OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES

(50,844 sq. miles), and very much larger than the United King-

dom (94,209 sq. miles).

The largest island in the Philippines is Luzon (40,814 sq.

miles), which is bigger than Hungary (35,918 sq. miles) or Portugal (35,510 sq. miles). Mindanao, the second largest island,

(36,906 sq. miles) is bigger than Austria (32,374 sq. miles).

The northernmost point of the Philippines is Y’Ami Isle, —

which is 78 miles from Taiwan and the southernmost point ts

Saluag Isle, only 34 miles east of Borneo. On a clear sunny

day, Taiwan

Saluag Isle.

is visible from Y’Ami,

and Borneo

visible from

Since 1956, the Philippines has declared an archipelago

principle of internal waters, meaning that the islands, waters

and other natural features of the country are to be regarded as

a single geographical, economic and political unit. Subsequently,

the archipelago principle was established in our national legisiation, most recently in Article 1 of the 1986 Constitution. Through

the United Nations Conyention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which was signed by 117 states in Jamaica, on December

10, 1982, the Philippine Delegation won recognition for the

archipelago principle, which is a distinct Philippine contribution

to international law.

This legal milestone has far-reaching implications. The various islands of archipelago nations (e.g. the Philippines, Greece,

Indonesia, etc.) will no longer be regarded as separate units,

each with its own separate territorial sea. We have secured

sovereign title over our overall archipelagic waters, the air space

above them, the seabed and subsoil below them, and the

resources contained therein.

The 1982 UNCLOS Treaty also designated a new concept

of the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), or a 200-mile belt of

water around our archipelago (subject to agreement with

neighboring countries whose Zones cross our own). Within this

EEZ, the Philippines has the sovereign right to explore, exploit,

conserve and manage the natural resources of the ocean, the

seabed and the subsoil.

Geographical Foundations of Philippine History

‘The following table includes new povsrapmical data on Philippine territory:

Land Aréa (3° > 08.4

ps

Total Area with UNCLOS

Treaty

ee one EAA, 707 sq. miles

Total Area under Economic Zone

of 200 miles from baselines

. .520,700sq. nautical

miles

. . .625,800sq. nautical

miles

Physical Features. The Philippines iisa rugged land of mountains and plains, bays and lakes, rivers and waterfalls, valleys

and

volcanoes.

Its irregular coastline

stretches

10,850 statute

miles, twice as long as the coastline of the United States. The

highest mountain is Mount Apo (9,600 feet high) in Mindanao.

The lowest spot in the world is the “Philippine Deep”, situated

off the Pacific coast of the archipelago. It is 37,782 feet deep,

or 2,142 feet lower than the “Marianas Deep” (35,640 feet

deep). Mount Everest (29,028 feet high), the highest mountain

in the world, can easily be submerged in the “Philippine Deep”,

with 8,754 feet of space to spare.

Between Samar and Leyte is the picturesque San Juanico

Strait, “the narrowest strait in the world”. Manila Bay, with the

historic Corregidor Island standing guard at its entrance, is one

of the finest harbors in the Asian world.

The largest plain is the Central Plain in Luzon. It is famously

known as the “‘Rice Granary of the Philippines’”’. The Cagayan

Valley, also in Luzon, is Asia’s greatest tobacco-producing re- —

gion. It is drained by the Cagayan River, longest river in the

Philippines. Near Manila is the picturesque Laguna de Bay, the

largest lake in the country.

Climate. Philippine climate is tropically warm, but healthful.

According to the American

scientist, Dr. Dean C. Worcester,

who resided for many years in Manila, it is “one of the most

‘healthful tropical climates in the world’”’.'* There are two distinct

seasons, the dry and the wet. The dry season lasts from March

to June, while the wet season is from July to October. The

intervening months of the year — November to February — are

neither too dry nor too wet. It is the Philippine springtime, a

delightful season of the year.

HISTORY OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES

There is abundant sunshine all year-round, so that in thea

Philippines, flowers of all kinds bloom everyday. There is also 4

plenty of rain. The Philippines holds the world’s record for the

_

heaviest 24-hour rainfall of 979.4 mm. which occurred in Manila

on October 17, 1967.

Typhoons. The Philiopiacs lies within the path of theSa a.

typhoons which are spawned in the Pacific Ocean. For this

reason, the archipelago is lashed by terrific typhoons annually,

taking a heavy toll. of human lives and property. Prior to 1963

the destructive typhoons that hit the Philippines were named

Gertrude, Jean, Joan, Kate, etc. After this date, the annual —

typhoons were given Filipino women’s names, such as Auring, B.

Bering, Didang, Edeng, Gloring, Konsing, Sening, Yoling, etc.

The word “typhoon” originated from the Chinese term a

’ taifung which means “strong winds”. The first recorded typhoon _

to lash the Philippines was in 414 A.D., which was recorded by

the famous Chinese Buddhist priest-traveler, Fa-hien. He was

caught by this typhoon which almost wrecked his ship during —

his homeward voyage from Sumatra to China: This horrendous

_

typhoon devastated a wide area, inguciae Borneo, the Philippines and South China.

Among the destructive typhoons which smashed the Philippines in recent years were the following: Dading (June 29, 1964), _

Meding (September 2, 1970), Sening (October 13, 1970). Titang

(October 28, 1970), Yoling (November 19, 1970) and the six .successive typhoons of 1972 — Asiang, Biring, Konsing, Didang,

Edeng and Gloring — which flooded the towns and cities of

_central Luzon, Greater Manila, and southern Tagalog provinces.

All these typhoons caused staggering losses of human lives and 3

property.

ee

Earthquakes. The Philippine Neiipelaes perches precariously along the “‘ring of fire” of the Pacific world which stretches

from New Zealand, through Indonesia, the Philippines, Japan,

_

California, to Alaska. Consequently, the country is rocked from

time to time by earthquakes or seismic tremors.

There are over 100 seismic faults in the archipelago, including

i

_ the Philippine fault, which runs from western to southern Luzon.

The most frightful earthquake to rock Manila during the 7

Spanish period occurred on the evening of June 3, 1863, the y

6

Geographical Foundations of Philippine History -

eve of Corpus Christi celebration. It destroyed the Manila

_ Cathedral, the palace of the Spanish governor general, many

churches, other public buildings and numerous private homes.

2 More than 400 people were killed and more than 2,000 injured.

_ The damage to property (public and private) reached 8,000,000

_ pesos — a massive amount during that time. Among the victims

of this earthquake was the famous Filipino priest-patriot, Father |

. Pedro Pelaez, valiant champion of the rights of the Filipino

_ clergy. He was praying before the altar of the Maniia Cathedral

_ when it collapsed, crushing him to death.

On the night of “Black Friday”, August 2, 1968, Manila

_ -was rocked by a disastrous earthquake of magnitude

6.5 to 6.9 |

on the Richter scale, with epicenter in Casiguran Bay.~It

__ destroyed the new Ruby Tower and damaged other buildings in.

_the city. It also killed 270 people (mostly Chinese residents at

_ the Ruby Tower) and injured 261. The property losses amounted

to more than P4 million.

The most destructive earthquake in the recorded history of

: the Philippines occurred on August 17, 1976. With a-tremendous

. force of 8.2 magnitude on the Richter scale and accompanied

by heavy tidal waves, this killer earthquake (with epicenter in

the Moro

Gulf) hit Mindanao,

Basilan,

Jolo and Tawi-Tawi,

killing 9,149 people, rendering 35,000 families homeless

destroying private pepe

worth 500 million.

Ay

weeny

and

Volcanic Eruptions. There are more er 50 volcanoes in

_ the Philippines, the majority of which are fortunately inactive.

_ Most famous of these volcanoes is Mount Mayon. A joy to

behold because of its peerless beauty, it has a grim and tragic

history. It has erupted some 40 times from 1616 to the present,

causing terrible losses in human lives and property in Bicol. —

The most cataclysmic eruption of Mount Mayon occurred

on February 1, 1814. The avalanche of its flaming rocks and

_ molten lava destroyed the town of Cagsawa and killed 1,200

people (men, women, and children). Only the tower of the

_ buried town remains above the promad, a silent witness to the

_ dolorous tragedy.

- Another famous Philippine volcano is the tiny Taal volcano

in

Taal Lake, Batangas province.

It has had over two

dozen

recorded eruptions since 1572. Its most destructive eruption

7

HISTORY OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES

occurred on January 30, 1911, when its thunderous explosions

were heard hundreds of miles away, as far as the Cordilleras in

the north, and its ashes spread far and wide and fell on Manila,

—

the towns of the southern Tagalog region and central Luzon.

At the time, thirteen villages around Taal Lake were Gestaye

and 1,300 people perished.

Other volcanoes in the Philippines are Babuyan Claro in

the Babuyanes; Didicas, also in the Babuyanes; Bulusan in —

Sorsogon; Kanlaon in Negros Occidental; Hibok-Hibok in Cami- —

guin Island; Calayo in central Mindanao;

Mindanao; and Bud Dajo in Sulu.

Ragang in western

§

Fauna. The Philippines abounds in animal life. Most useful13

of Philippine animals is the carabao (water buffalo), the farmer’s —

best friend. Gentle as a domestic pet and slow as a turtle, it is

a reliable work-animal like the elephant and is used for pas

ricefields.

More than 750 species of birds, more than those in Australia,

Japan, or any other country of Southeast Asia, are found in the

Philippines. The biggest Philippine bird is the Sharpe’s Crane

(Crus antigone sharpei), known as tipol in Luzon and labong in

the Visayas. It is a wading bird, with very long legs and neck,

and is almost as tall as a man. Its color is pearl gray, with bright

scarlet plumage on its upper neck. The largest eagle in the world,

called the monkey-eating eagle (Pithecopaga jefferyi), is found

in the jungles of Luzon and Mindanao. It is the “King of Philippine Birds”. When full grown, it measures five and a half feet

in height -with a wing span of seven feet. It is now one of the

—

—

endangered species of animals in the world and has attracted

the attentionof conservationists, notably Dioscoro Rabor of the

Philippines and Charles Lindberg of the United States.

Other interesting birds in the Philippines are the kalaw,

which the Spanish colonizers called “‘the clock of the mountains”

because it makes a loud call from the mountains at noon daily;

the woodthrush, sweetest troubadour of Philippine skies; the

—

katala, which talks and sings like a human being; the tiny Philippine falconet, measuring only six and a half centimeters long,

said to be the world’s smallest falcon; the Palawan peacock —

pheasant which struts gracefully like an adagio dancer; and the —

limbas, a hawk which screams as it soars into the sky, “tik-wee,

tik-wee, tik-wee’’.

Geographical

Foundations of Philippine History

:

Four unique animals in the world are found in the Philip_ pines. They are the tamaraw (Bubalus mindorensis) of Mindoro,

_ which looks like a dwarf carabao and is fierce like a tiger; the

_ tarsius of Bohol, which is reputed to be the smallest monkey in

_ the world; the mouse deer (pilandut) of Balabae Island of Pala- wan’s coast, which is the world’s smallest deer; and the zebronkey,

half-zebra and half-donkey, which was bred at the Manila Zoo

in 1962.

There are about 25,000 species of insects in the Philippines.

_ The largest Philippine insect is the giant moth (Attacus atlas),

_which has a wing span of one foot.

Flora. Millions of flowers of all colors and scents bloom all

_ year-round throughout the Philippines. For this reason, many

_ authors call the archipelago the “Land of Flowers’. There are

_ about 10,000 species of flowering plants and ferns in the Philip_ pines.

Among the beautiful flowers of the Philippines are the lovely

_ sampaguita, the charming cadena de amor (chain of love), the

_romantic gardenia, the milky-white camia, the bewitching dama

de noche (lady of the night), the stately banaba, the alluring

_kamuning, the colorful kakawate and the majestic bougainvillia

_ of various colors.

The largest flower in the world is the pungapung

grows wildly in the forests of Mindanao.

- one foot.

.

which

It has a diameter of

About 1,000 varieties of orchids: bloom in the Philippines.

- The waling-waling (Vanda sanderiana), a rare orchid of exquisite

beauty, is regarded as the “Queen of Philippine Orchids”.

Numerous ‘kinds of fruits grow in abundance in the country.

_ Among the famous Philippine fruits are the delicious lanzones,

- the ‘Queen of Philippine Fruits”, the sweet mango, the “Czarina

of Philippine Fruits” and the nutritious. durian, the “King of

Jungle Fruits”.

the

Sampaguita, Philippine National Flower. Most famous of

Philippine flowers is the sampaguita (Jasminum sambae)

_ which was proclaimed as the national flower of the Philippines

by Governor General Frank Murphy on February 1, 1934. It is

a lovely flower, snow-white in color and gently fragrant like a

9

HISTORY OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES

lady’s perfume. It possesses the regal grace of America’ s wild

rose, the creamy purity of France’s fleur-de-lis, the fascinatin

beauty of China’s sacred lady, the scented effulgence of Japan

chrysanthemum and the tropic charm of Hawaii’s hibiscus.

It is customary for visitors to wear garlands of sampaguitas,

a custom peculiar to the Philippines as the wearing of flowe

leis in Hawaii. Thus rhapsodizes the romantic Manuel Bernabe

e Sener ee poet in Spanish:

What a graceful flower

is the Sampaguita

Whoever wears it not

Is no. Filipina.

More than a national flower, the sampaguita is a flower of

love. In early times a Filipino lover, to express his love to

girl, customarily sent her a necklace of sampaguitas. If the gi

wore it around her neck, it meant that she reciprocated his offe

of love. They then plighted their love in the moonlight with the

words in Tagalog; ““Sumpa kita’ (we pledge). From these words

' originated the flower’s name — sampaguita. *

Agriculture and Agricultural Wealth. “Agriculturally,” sai

Dr. Frank C. Carpenter, American traveler-author, “the Philippines are among the richest lands on earth.”’!° God has generously

endowed the country with fertile soil and favorable climate.

Agriculture is the greatest industry of the Filipino people. The

potential farming area of the Philippines is 18,000,000 hectares,

of which only one-third is cultivated.

The major farm crops are rice, coconuts, corn, hemp, sugar

and tobacco. About 1,000 varieties of rice, the people’s staple

food, are grown in the Philippines. Other agricultural products

of the country are rubber, bananas, pineapples, cabbages, onions,

mangoes, lanzones, legumes and camotes. Three temperate farm

products — apples, grapes and wheat — have been successfully

cultivated in recent years.

Among the countries of the world, the Philippines ranks

first in coconut and hemp production, second iin sugarcane, and

fifth in tobacco.

Forests and Forest Wealth. Forests are one of the rice

natural resources of the Philippines. Forest ee total 16 633, 000

~

10

- Geographical Foundations

of Philippine History

=

representing 55% of the total land area. Of this total

forested area, 14,452,650 hectares are commercial forests and

eZ 180,000 non-commercial forests. In the Asian world, the Philippines ranks third in forest reserves, the first being Indonesia

_and the second, Japan.

.

_

There is much wealth in the Philippine forests.. There are

;

3,800

species of trees in the forests. Of great demand for construction purposes are the timber of the almon, apitong, guijo, ipil,

red and white lauan, narra, tangile, tindalo, and yakal. Aside

from timber, the Philippine forests yield valuable

dyewoods,

“medicinal plants, ore (tanbark), guttapercha, resins, nipa palms

and rattan.

4

Unfortunately, the . Philippine forests have been destroyed

_by illegal logging, fires and slash-and-burn (kaingin) farming.

The wanton destruction of forests has proceeded at the rate of

170,000 hectares a year, one of the fastest rates of denudation

in the world. At this alarming rate of destruction, the Philippines

could become deforested within a few decades.

.

ae

E

_Narra, Philippine National Tree. Most famous of the Philip-

pine woods is the narra (Pterocarpus indicus), which is regarded

‘byforesters as the “Queen of Philippine Trees’. It is the national

age of the Philippines, in accordance with an executive procla-

ation of Governor General Frank Murphy dated February 1,

“1934. In the Philippine forests, it may be seen towering in

“Majestic height, with a crown of golden flowers. It is a massive

frank clothed with a soft grayish bark that exudes a scarlet liquid

:

of great value for dyeing and medicinal purposes.

The narra is symbolic of Filipino eases

a

the Filipino Forest Ranger Jose Viado, says:'°

and ideals. As

It is a tall tree, which characteristic seems to be expressive

of the lofty aspiration of the people to be one of the independent nations of the world. It is stalwart and enduring, which

fact could be taken to signify the steadfast persistence of the.

Filipinos in their demand for freedom. While other trees are

bent or uprooted by tempests, the narra tree usually with- .

-

stands such disaster. a storm may strip it of its leaves and

break off its smaller branches, but the tree itself remains

upright. As the narra resists the tempest, so has the Filipino

_. fought his oppressors.

11

HISTORY OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES

When the bark of the narra is injured, red sap oozes —

out — a constant reminder of the blood that has consecrated

Philippine soil in the numerous daring attempts of the

Filipinos to free their country from foreign domination, and

of the blood still running through the veins of the people,

ready to be shed upon their country’s call.

During certain parts of the year, the narra tree sheds

its foliage, and new leaves grow. Every year it grows anew,

undergoes rejuvenation. This symbolizes the disappearance

of old customs

and their replacement by new ones, or, in

other words, the onward march of progress.

The narra tree is known by different names in different

regions of the Philippines. It is called asana in the Tagalog

provinces of Laguna, Quezon, Batangas, and Cavite; dungon in

the Cagayan Valley and Ilocandia; apalit in Pampanga and Tarlac;

nega in Palawan and the Visayas; and bitali in Zamboanga,

Mindanao.

The narra has a thousand uses in the daily life of man. It

is carved by skilled Filipino woodcarvers into statues of Catholic

saints. It is made

into beautiful chairs, tables, cabinets, beds, —

dressers and other kinds of furniture.

It is also used in the

construction of ceilings, floors, and walls of aristocratic homes

and swanky offices. Because of its beauty and durability, it is

highly in demand for building and ornamental purposes.

Fish and Marine Wealth. Philippine rivers, lakes and seas

teem with fish, shells, pearls, corals, seaweeds and other forms

of marine wealth. More than 2,000 species of fish are found in

Philippine waters. Among the commercially known fish found

in the numerous fishing grounds of the archipelago are the banak

|

—

(mullet), bangus (milkfish), dalag (mudfish). dilis (anchovy),

kandule (catfish), lapulapu (seabass), talakitok (pampano), tamban and tunsoy (sardines), -tanguingui (mackerel), and bariles

(tuna).

Both the largest and the smallest fish in the world are found

in the Philippines. According to marine biologists, the world’s

largest fish is the whale shark (Rhineodon typus), which is 50

feet or more in length and weighs several tons when fully grown.

It was first sighted off the coast of Mariveles, Manila Bay, in

1816 by Filipino fishermen, who called it pating bulik (striped

shark) because of the black stripes on its body.

|

12

Geographical Foundations of Philippine History

The smallest fish in the world is Pandaka pygmaea (dwarf

pygmy). It was discovered in 1925 by Dr. Albert Herre, American

ichthyologist, in the Malabon River which empties into Manila

Bay, and rediscovered in 1951 by the Filipino ichthyologists,

H.R. Rabanal, Inocencio Ronquillo, and Artemio Sarenas, at

the Dagatdagatan Salt-Water Fishery Experimental Station in

Malabon.'* Although native of the Philippines, Pandaka pygmaea

has no native name yet. Its average length is 9.66 millimeters,

being 3 millimeters smaller than the famous sinarapan (Mistichtvs

luzonensis) which exists in Lake Buhi, Camarines Sur. Formerly,

the sinarapan (also known locally as tabyos), which was discovered in 1902 by Dr. Hugh M. Smith in Lake Buhi, held the

title of “the smallest fish in the world”. Now it may be called

“the world’s second smallest fish’.

Aside from fish, the Philippine waters yield other marine

products, such as shells, snails, crabs, shrimps, sponges, turtles,

corals, pearls and edible seaweeds. Of the 60,000 species of

shells known to man, about 10,000 are available in the Philippines. The world’s rarest and most expensive shell, called “Glory.

of the Sea” (Connus gloriamaris), is found in the Philippines.

Also found in the archipelago are Tridacna gigas, the world’s

largest shell which has a length of one meter and weighs 600

pounds, and Pisidum, the smallest shell in the world, which is

less than one millimeter long. One of Asia’s great spawning

grounds of huge sea turtles is the Turtle Islands in the Sulu Sea.

Along the sandy beaches of these islands are found numerous

turtles, whose meat and eggs are a gourmet’s delight.

Beneath the seas of Palawan and Sulu are located Asia’s

’ rich pearl beds. Since immemorial times many pearls of fabulous

beauty and value have been obtained from these pearl beds by

expert native divers. The world’s largest natural pearl, called

“Pearl of Allah’”,’® was found in 1934 in the Palawan Sea by a

Muslim Filipino diver. Said to be 350 years in age, it is 9 1/2 x

5 1/2 inches in size, and 14 pounds in weight, and was valued

- at $3.5 million. The local Muslim chieftain gave it as a gift to

Wilburn Dewall Cobb of California in 1936 for saving the

life of his sick son.

Minerals and Mineral Wealth. The country has rich deposits

of gold, silver, iron, copper, lead, manganese, zinc, and other

metals, coal, cement, salt, asphalt, asbestos, gypsum, clay, marble

13

—

HISTORY OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES

and other non-metallic minerals. Vast reserves of oil and gas

have been found and exploited both iniand and offshore. And

the Philippines contains one the richest potential reserves of

seabed mineral nodules, lying at the bottom of the sea.

The Philippines is one of Asia’s greatest gold-producing

regions. Gold mining is an ancient industry in the archipelago. —

long before

the coming

of the Spanish conquistadores

the

Filipinos were already mining gold in Paracale (Camarines

Norte), in the mountains of northern Luzon and in the islands

of Masbate and Mindanao.

Copper mining is another old industry in the Philippines. :

The Igorots have been mining copper in the mountains of northern

Luzon since pre-Magellanic times. The best known copper district

is Mankayan, where the oldest and largest copper mine still —

- exists. Other copper deposits are found in Rapu-Rapu Island

(part of Albay Province), Negros Island and Zambales Province.

The greatest iron-bearing area in the Philippines is Surigao,

whose iron ore deposit is estimated at 1,000,000,000 tons, being

“one of the richest undeveloped deposits in the world”. Other

_rich iron ore deposits are in Angat, Bulacan; Larap, Cama

Norte; Marinduque; and sae

th Masinloc, eee exists “‘the biggest deposit of high.

quality chromite in the world”. The world’s largest deposit of

nickel has been discovered in recent years in Nonoc Isle, off

the coast of northern Mindanao.

Adequate deposits of coal are found in Cebu, Polillo Island, |

Sorsogon, Masbate and Sibuguey Peninsula, Mindanao; oil in

Bontoc Peninsula and the Cagayan Valley, Cebu and other

Visayan Islands, and the coastal areas of Palawan and Sulu; lead

and, zinc in Masbate; tin and quicksilver in Palawan; asphalt in

Leyte; asbestos in Ilocos Norte and Zambales; marble in 4

Romblon and Mindoro; cement in Cebu, Rizal, and La Union;

and sulphur in Camiguin Island, Biliran Island (near Leyte),

and Mount Apo, Mindanao. There are vast marble deposits

reaching 600,000 tons in Mindoro, Romblon, Palawan, Cebu

and Bicol. According to Asher Shadmon, United Nations marble ,

expert, the Philippines has the potential to become “the world’s

top producer of marble”.

14

Geographical Foundations of Philippine History

Although most of her rich mineral resources are still underdeveloped, the Philippines is already the largest copper and

: chromite producer in the Far East and ranks as one of the first

five among the world’s producers for refractory chromite.

Water Power. Water iis used not only for bathing, cooking,

drinking and irrigation purposes, but also for power to turn the

wheels of industry and to furnish electric light to homes, offices

and factories. By harnessing the rivers and waterfalls in the

_ archipelago with turbine machines, hydro-electric power can be

- generated which, according to the famous Bewster Report of

1947, is sufficient “to meet the entire commercial and. domestic

requirements of the country. “At present, the Philippine government has already established hydro-electric power plants at the —

_ Caliraya Dam and Botocan Falls in Laguna, at Ambuklao and

Binga in Northern Luzon, Maria Cristina Falls in Mindanao and

the Pampanga River Hydro-Electric

locatedin Pantabangan, Nueva Ecija.

Project,

whose dam

is

Geothermal Energy. Geothermal energy from hot springs is

a new power source in the Philippines. Numerous hot springs,

~ especially in Luzon and Visayas, have been tapped as sources

of geothermal energy: This new source of power for homes and

_

industry makes the Philippines second only to the United States

ee

in geothermal energy development.

a “=

=

Scenic Beauties and Natural Wonders.

The Philippines ‘is

one of the world’s most beautiful countries which God has

embellished with scenic beauty and natural wonders.4_ike glamor-

ous Hawaii, she has velvety beaches where the surge of the seas

murmurs in eternal monotone;'like picturesque Indonesia, she

-has towering highlands garlanded with gossamer-white mists of —

the morning; like enchanting Maiaysia, she has palm-fringed

shores and glistening streams beneath the canopy of azure skies;

_ like picturesque Japan, she has scenic countrysides with eternally

blooming flowers and filled with gay melodies of singing birds;

and like sunny Spain, she has verdured vales and old pueblos

basking redolently within the shadows of church belfries.

World famous are the Banaue Ifugao Rice Terraces in north-

ern Luzon.'? Built more than 2,000 years ago by the hardy

Ifugao farmers on the massive slopes of the mountains, these

: terraces rise in gigantic steps toward the clouds. If placed end

to end,

they would

extend

14,000 miles

— almost ten times

15

HISTORY OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES

longer than the famous Great Wall of China — more than half

of the earth’s circumference. In beauty and symmetry of design

and in durability and massiveness of construction, these rice

terraces can favorably match any epemecyes masterpiece in the

world.

Foreign travelers who have seen the Rice Terraces of Banaue ~

marvel how the ancient ancestors of the Ifugaos, untrained in

engineering science and using only their crude iron tools and

bare hands, could have carved such wondrous irrigated paddies,

on the steep and rocky mountain slopes. No wonder, the Banaue

Rice Terraces have been acclaimed by many writers as the

“Eighth. Wonder of the World”.

The crowning glory of the natural wonders of the Philippines

is Mount Mayon in Albay Province, Southern Luzon. Its majestic

beauty thrills all beholders. It surpasses the famous volcanoes

of the world in beauty, for it possesses “‘the most beautiful

symmetrical volcanic cone”’.7? ©

Another Philippine volcano which fascinates global tourists

is the tiny Taal Volcano at the center of Lake Taal in Batangas.

It is reputed to be the smallest volcano on earth.

Other wondrous sights in the Philippines are the world-famous Pagsanjan Falls; the legendary Mount Banahaw; the Hidden

Valley in Laguna; the inland Sampaloc Lake in San Pablo City;

the amazing Umbrella Geyser of Barrio Bigas, San Juan, Batangas; the fabulous “submarine gardens”’ off the Latya coast between the Lobo and San Juan towns in Batangas Province; the

attractive Matabungkay Beach in Lian, Batangas; the lovely

Sunset Beach of Cavite; the awe-inspiring Montalban Caves in

Rizal; the picturesque Hundred Islands of Lingayen gulf, Pangasinan; the enchanting Crystal Caves near Baguio City; the sparkling

Salinas Salt Springs in Nueva Vizcaya; the enthralling Callao

_Caves in Cagayan; the volcanic Tiwi Hot Springs in Albay; the

_ fascinating White Beach of Legazpi City; the romantic Bulusan

Lake in Sorsogon; the roaring Darosdos Falls in Samar; the

scenic Talisay Beach in Cebu; the storied Guimaras Island and

Roca Encantada

Island in Iloilo; the fabulous Chocolate Hills,

more than 1,000 of them in Bohol; the idyllic Lake. Lanao and

the magnificent Maria Cristina Falls in Mindanao; the enigmatic

Underground River in Palawan: and the alluring Kawa-Kawa

Beach in Zamboanga City.

16

Geographical Foundations of Philippine History

The gorgeous sunset in the Philippines, another of God’s

blessings to the Filipino people, is unmatched anywhere in beauty

and charm. As Dr. Worcester affirmed: “‘Philippine sunsets are

unsurpassed and unsurpassable.” The Manila Bay sunset, in

particular, is unanimously haftled by foreign authors and tourists

_ as “the most beautiful sunset in the world”. In the somnolent

solitude of the gleaming tropics, it is most inspiring and thrilling

to behold. Truly, the memory of its exquisite beauty lingers in

the beholder’s heart like a nostalgic echo of an unforgettable love

song of long ago.

:

*

*

KX K

*

17

Ae <n a

Te

2

The Philippines as a Unique —

Nation in the World

GEOGRAPHICALLY,* The Philippines is in Asia, but :

' by race and culture, Filipinos are a harmonious blend of the —

East and the West. Their Western heritage, largely acquired.

from Spain and America, has made them distinctly different

from other Asian nations. Because of Christianity and Islam,

their Eurasian and American education and customs, and their

intelligent assimilation of Asian, Latin, European and American

civilizations, they are eminently qualified to bridge the East and

the West. According to an American writer, Dr. Frank C.

Laubach, ‘“‘The Filipinos are in a position to be, and many of

them are today, the most cosmopolitan people on earth. White

men may be cosmopolitan so far as Orientals are concerned;

the Chinese may be cosmopolitan as far as the Orientals

are —

concerned: but who, save a Filipino, can feel equally at home in

a palace in Peking, in the White House in Washington, or ina ~

salon in Paris?”!

_ Unique in the World. Of all nations, the Filipinos are unique

not only in Asia but also in the world, due to the following

reasons:

4

—

(1) their religion; (2) their political history; and (3)

their cultural heritage.

_ Firstly, Filipinos are predominantly Christian in the Asian

region where other nations are Islamic, Buddhist, Shinto, Con-

fucian, polytheistic and animistic in beliefs. The Philippines has

served as Christianity’s lone citadel beneath Asian skies and the

light from which the gospel of Jesus Christ has been preached

to other Asian countries.

_

Secondly, the Philippines is the first Republic in Asia, being 4

the first Asian nation to achieve independence by revolution and

establish a Republic, led by General Emilio Aguinaldo in 1898-- |

18

The Philippines as a Unique Nation in the World

_ 1901. It was the first southeast Asian nation to secure independence by the voluntary decolonization of a colonial power after

the Second World War in 1946.

And finally, Filipinos are unique in Asia for culturally and

scientifically assimilating four heritages— the indigenous Asian,

the European, the Latin and the American heritage. Our history

is indeed unique for the variety, the intensity and the duration

_ of our political, cultural and scientific relations with other nations.

_

Origin

of

the

Filipinos.

The

accepted

theory

among

ethnologists is that the Filipinos originated from the blending of

three Asian peoples during prehistoric times — Negritos, Indonesians, and Malays. In the ebb and flow of succeeding centuries

their racial stock was invigorated by interracial mixture with

other Asian peoples — Indians, Chinese, Arabs and Japanese,

~ and still later, with the Western peoples — Spaniards, Americans,

French, English and other European peoples.

RN

fee,

PR

OMe

Imaginative folklorists recount two legends regarding the

- origin of the Filipinos. The first one is as follows.”

_ Long, long ago, after the land was formed as a result

of the war between

Ssfaaa

seed

:

TR

PM

Se

MOS

PRET

IM

en

Oper

Nee

nL

ORES

RAE

seme

the sea

and the sky, the clever bird,

which incited that war, flew ashore. It alighted on a bamboo

plant in order to rest. While resting it happenedto peck on

the bamboo. Suddenly, the bamboo split lengthwise. Out of

the first nodule emerged a man, and out of the second

_

nodule, a woman. The man was named Lalake, and he was

~ the first man in the world. Ses woman named sawed was

the first woman in the world.

Lalake and Babae married. Many children were born to

them. From these children originated the Filipinos.

The second legend, more interesting than the first, runs as

- follows:*

Many, many ages ago, dere were no people on earth.

One

day the gods walked about the earth and found that it

was lonesome. They decided to create the people who would

_ inhabit the plains and hills. They tarried by a riverbank,

where there was plenty of clay. They moulded the clay into.

male and female figures and. baked them over a slow fire.

Owing to their lack of experience in baking, they baked the

clay figures too long so that p were burned to blackish

color.

19

: HISTORY OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES

Dissatisfied

with

the

product

of their

baking,

they

—

moulded another set of clay figures and placed them over

the fire. Because of their first failure, they became over-cautious and took away the clay figures from the fire before they

could be toasted right. They were chagrined to see that the

clay figures were whitish, being underbaked.

For the third time, the gods, undaunted by their previous

failures, moulded another set of clay figures and put them over the fire. This time, having enough experience in baking,

they succeeded in baking the figures perfectly.

Then the gods breathed life into all the baked clay

figures. Out of the overbaked clay figures sprang the black

race, out of the underbaked figures emerged the white race,

and out of the perfectly baked figures arose the brown race.

The brown-skinned Filipinos are thus the perfect handiwork

of the gods.

{

A Race of Races. Predominantly Malayan in race, Filipinos

are virtually a race of races. In their veins flow the bloods of

both East and West. According to Dr. H. Otley Beyer, eminent

American anthropologist, the proportion of racial mixture in

Filipino veins is as follows: Negrito, 10% Indonesian, 30%,

Malay, 40%; Chinese, tae Indian, 8%; European and Ameri-

can, 3% and Arab, 2%.*

Contrary to Kipling’s imperialist dictum that “East is East —

and West is West, and never the twain shall meet”, the East

and the West meet and blend inthe Filipino. Filipinos likewise

expose the fallacy of Hitler’s Concept of Aryanism.by proving

that the mixture of races produces a vigorous, sturdy and intelligent people. ‘The Filipinos,” said Dr. F. M. Keesing, distinguished authority on Pacific ethnology, “‘draw their physical and

mental heritage upon the stuff of practically all mankind. We

may credit them with being on the average under no biological

handicap as a people.’ And in the words ef President Manuel

L. Quezon, who was given the accolade by Roy W. Howard as

one of the greatest statesmen of the 20th century: “The Filipino

is not inferior to any man of any race. His physical, intellectual

and moral qualities are as excellent as those of the proudest

stock of mankind.’”®

on Filipino Nation. Filipinos consider themselves as a

nation.’ They dislike being mistaken for Chinese, Japanese,

Koreans or other Orientals. As Filipinos, they proudly aspire

to impress their mark in global affairs.

20

The Philippines as a Unique Nation in the World

The vast majority of Filipinos consists of the Tagalog, Vis-

ayans, Ilocanos, Bicolanos, Pampangueiios, Pangasinanes, Ibanags

(Cagayanos) and Zambals. They are the descendants of the

islanders who had been conquered by Spain and later by America

and

were

consequently

Americanized.

Christianized,

Hispanized

and

Also forming part of the Filipino nation are the non-Christian

minorities, such as the Muslims of Mindanao and Sulu, whom

the Spanish invaders called Moros; the Ifugaos, Bontoks,

Apayaos, Benguets and Kalingas of the Mountain Province; the

Mangyans of Mindoro; the Tagbanuas of Palawan; the Bagobos,

Manobos,

Isamals and Subanuns of Mindanao;

the Badjaos of

_ the Sulu Sea; and the Negritos of the hinterlands. These nonChristian

_ America.

Although

language,

Filipinos were not fully conquered by either Spain or

Hence, they have retained their ancestral heritage.

they differ from their Christian brothers in religion,

dress: and customs, they are Filipinos,

Philippine Population. The total population of the Philippines

at present is 56 million. It is the 16th most-populated country

in the world and has experienced a population explosion problem _

since after the Second World War. The majority of Filipinos are

young — those below 15 years of age alone make up 44% of

the population — unlike in other countries where there are more

older and productive people than young and dependent ones.

Another important feature of the population is the migration

of many talented and hard-working Filipinos to other countries

to seek a better life. The Middle East has attracted Filipinos as

temporary workers; the U.S., Canada, Australian, and European

countries have large Filipino expatriate communities. The nation

has lost many of its professionals, skilled and semi-skilled workers

in what is known as the “brain drain” phenomenon.

Because of the population problem, the government has

undertaken a vigorous policy of family planning which has slowed:

down the rate of population growth from 3.01% in 1970 to 2.4%

in 1982.

Asia’s Only Christian Nation. The Philippines is the only

Christian nation in Asia. Over 93% of the Filipinos are Christian,

and the rest are Muslim, Iglesia ni Kristo or other beliefs. Of

the Christian Filipinos, 85% are Roman Catholic; 7% are

zi

—

HISTORY OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES

Aglipayans (members of the Philippine Independent Chui):

and the rest are Baptist, Methodist, Lutheran and other evangelical churches.

A Nation of Many Languages. Filipinos are known. for their

talent in languages. This is exemplified by Dr. Jose Rizal, Philippine national hero, who knew twenty-two languages.

According to the findings of the Summer Institute of Linguistics of the University of North Dakota (headed by Dr. Richard

S. Pittman),

there

are

55 languages

and

142 dialects

in the

Philippines.* Dr. H. Otley Beyer’s work in 1916 listed only 43

major languages and 87 dialects.

Of the native languages, Cebuano is; spoken by nearly onefourth (24.39%) of the population; closely followed by Tagalog,

the mother tongue of about 23.82% Filipinos. Other major native

languages are Hocano, Hiligaynon, Bicol, ra Kapampangan,

and Pangasinan.

Only

English

and

Spanish-speaking

Nation

in Asia.

~

The

Filipinos are also the only nation in Asia who speak English

and Spanish and have a literature written in these two foreign

languages. This is so because of the three centuries of Spanish

rule and the five decades of American occupation of the Philippines.

—

As a matter of fact, Filipinos take pride in being the third

largest English-speaking nation in the world. English is still

widely-known (spoken and written) in the country. However, ©

Filipinos may eventually lose their distinction as the world’s third

English-speaking nation because of the marked decline of the

English language in recent years on account of the government

policy of bilingual (Filipino and English) instruction in all schools

and the compulsory use of Filipino (also called Pilipino) as the

national language.

Spanish, one of the beautiful languages of mankind, is a

dying language in the Philippines. Presently, it isspoken by only

2.1% of the Filipino people, mostly by the elite.

The National Language.

Since the Commonwealth era of |

President Quezon, the country has adopted a Tagalog-based

national language, which is. called “Pilipino” or “Filipino.” Under ‘Article XIV, Section 6, of the 1986 Constitution, the national

22

The Philippines as a Unique Nation in the World

_

language is known as “Filipino.” It has now become the dominant

language, displacing English. Even Filipinos who speak other

_tegional languages like Cebuano, Waray, Hiligaynon, Bicol, etc.,

also read, write and speak Filipino after having studied it in

: school.

Most Literate Nation in Southeast Asia. The Philippines is

the most literate nation in Southeast Asia. The present rate of

literacy in the Philippines is 89.27%, the highest among the

Southeast Asian nations and also higher than the Arab nations

of the Middle East.

Such happy phenomenon may be attributed to the three

centuries of Spanish colonization and the five decades of American rule in the Philippines. Both these two colonizing powers,

it should be fairly admitted, extended to the people the blessings

of western education.

Another cause for the high literacy in the Philippines is the

passionate love of Filipinos for education. It is the magnificent

obsession of every Filipino to acquire formal education as a

means of improving one’s livelihood and status. As the last

American governor general of the Philippines, Frank Murphy,

said: “‘No people ever accepted the blessings of education with

more enthusiasm than the Filipino.”?

q

The Filipine Women. The women of the Philippines are the

freest among the women of the countries in Asia. Economically,

politically, and socially, they are the equal of the men. In fact,

they were the first Asian women to win the right of suffrage —

to vote in elections and to be voted to public offices. All professions are open to them —

law, medicine, nursing, engineering,

chemistry, banking, journalism, politics, etc.

Since early times, when the women in many Asian countries

were treated as inferior beings, and worse, as beasts of burden,

the Filipino women already occupied a high place in society.

They were accorded courtesy and respect and were treated with

chivalry by the men. As various Spanish writers of the earlier

centuries recounted, they were charmingly modest, religious and

morally beyond reproach. They were faithful to their husbands

and devoted to their children. Father Pedro Ordonez Cavallos,

writing in 1614, described the Filipino women as being “extremely

chaste”.'° And Fray Gaspar de San Agustin, noted Augustinian

historian, in 1698, harshly criticized the Filipino men, but praised,

the women “who are of better morals, are docile and affabie

and show great love for their husbands’’."’

23

~

.

HISTORY OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES

Filipino women are distinguished for their beauty. Evidently,

the blending of the Malay, Spanish and American blood in their

veins makes the women glamorously lovely and talented, enabling

them to win in various international beauty contests.

Filipino Character Traits. Like all peoples on earth, Filipinos

have bad and good character traits. Most scandalous of their

- character defects is their propensity for gambling. They would

bet for almost anything — whether or not it would rain the

following day, whether or not a certain candidate would win in

the election, or whether

the first child of a newly-wed couple

would be a boy or a girl. Their favorite forms of gambling are

cockfight, horse races, jueteng, black jack, poker, mahjong, and

monte.

Filipinos are inveterately extravagant. They love colorful fiestas, expensive clothes and jewelry and gay parties. No day ever

passes in the Philippines without a costly fiesta, for every barrio,

town and city in the archipelago has a patron saint, whose annual

feast day is celebrated with great extravaganza. Every baptism

of a child, every wedding, every birthday of a member of the

family and every school graduation

of a son or daughter is

celebrated with a joyous party.

Filipinos are fatalistic in their outlook in life. They tend to

believe that whatever happens, good or bad, is due to fate

(tadhana). So they accept with stoical resignation whatever happens to them, and face the future with the expression: “Bahala

na” the equivalent of the Spanish “Que sera, sera’ (What will

be, will be).

. Finally; the Filipinos tend to lack discipline and perseverance, a character trait caused perhaps by their tropical environment. They seem to have no stamina for long and arduous tasks. ©

Normally, they begin their work with great enthusiasm, but, like

a cogon fire which burns brightly for a brief time and then

flickers out, such enthusiasm soon disappears. This lack of sustained perseverance in work is expressed in a vernacular term

“ningas cogon”’ (short-lived flame of the cogon weeds).

These bad character traits of Filipinos are, however, offset

by their good traits. As the British trader-author, John Foreman,

who lived for many years in the Philippines, said: “The Filipino

has any qualities which go far to make amends for his shortcom- _

ings.”

24

|

bg

The Philippines as a Unique Nation in the World

|. Most admirable of the character traits of the Filipinos is

their proverbial hospitality. They receive all foreigners, including

their former foes in wars, “ their eee and homes with warm

hospitality and friendship.'*

They are famous for their close family ties and extended

family structures. Apart from being loyal to their blood relatives,

Filipinos adopt new kins (Kumpadre and kumadre) through having

male and female sponsors (ninong and ninang) during Babs

nand weddings.

Gratitude is another sterling trait of the Pilnino. They are

grateful to those who have given them favors or who are good

to them. Their high sense of gratitude is expressed in the phrase

“utang na loob” (debt of honor).

They are cooperative and value the virtue of helping each

other and other people. They cherish an ancestral trait of bayanihan (cooperation), which can mean helping a rural family move

their small hut to another place.

- Filipinos rank among the bravest peoples on earth. ‘They

aliantly resisted the Spanish, American and Japanese invaders

f their native land. To them, courage is a badge of manhood,

and it has been shown in Filipino soldiers’ service during battles

nd wars. More recently, millions of Filipinos armed only with

their faith and courage

peacefully won

over tanks, armored

carriers and planes during the ‘People’s Power’ Revolution of

February 22-25, 1986.

Owing to the effect of their beautiful country, Filipinos are

assionately romantic and artistic. They are ardent in love as

they are fierce in battle. They are also born musicians, singers,

artists and poets.

| They are highly intelligent, and foci to Dr. David P.

‘Barrows, an American educator, they have ‘quick perceptions,

hretentive memory, aptitude and extraordinary docility” making

them

‘most

teachable

persons.'* Prejudiced

writers during

Spanish times branded them as stupid and indolent.

| Finally, the Filipinos. are neted

resiliency. Throughout the ages, they

‘kinds of suffering

— invasions, revolts,

jquakes, typhoons, volcanic eruptions

for their durability and

have been lashed by ail

revolutions, wars, earthand epidemics. Probably

25

HISTORY OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES~

few peoples on earth, with the exception of the ieee the Chines

and the Russians have suffered as much as the Filipinos. Unlik

the Polynesians of the Pacific and the Indians of the America:

‘they have not vanished in contact with the Europeans. The

readily assimilate -any civilization and thrive in any climate

Against the winds of calamities which regularly visit their lanc

they merely bend, but never break, because they possess ‘th

formidable durability of the narra tree and the resiliency of th

bamboo.

a

xk

OK OK *

s

The Dawn of

Philippine History

be

_

-

*

THE DIM CENTURIES prior to Magellan’s

arrival in 1521

vere formerly unknown to historians. It is only in recent years

nat history’s frontiers have been explored by both historians

ind archaeologists. By means of intensive researches in ancient

asian records and by new archaeological discoveries at various

ites in the archipelago, new light has been shed on Aude

irehistory.

i First Man in the Philippines. According to recent archaeologcal findings, man is ancient in the Philippines. He first came

Hout 250,000 B.C. during the Ice Age or Middle Pleistocene

‘eriod, by way of the land bridges which linked the areIDeeE?

fith Asia. He was a cousin of the ‘Java Man,” “Peking Man,”

ad other earliest men in Asia. Professor H. Otley Beyer, emient American authority on Philippine’ archaeology and

§

athropology,

called him the “Dawn Man’,! for he appeared

i

the Philippines at the dawn of time.

_ Brawny and thickly-haired, the ‘‘Dawn Man” had no knowLage of agriculture. He lived by means of gathering wild edible

fants, by fishing, and hunting. It is probable that he reached |

ne Philippines while hunting. At that time the boars, deer, giant

nd pygmy elephants, rhinoceros, and other Pleistocene animals

pamed iin the country. Fossil relics of these ancient animals have

een found in Pangasinan and Cagayan Valley.

' In the course of unrecorded time the ‘‘Dawn Man” vanished,

jithout leaving a trace. Until the present time his skeletal remains

ifartifacts have not yet been discovered by archaeologists. So

ar the oldest human fossil found in the Philippines is the skull |

ap of a “Stone-Age Filipino”, about 22,000 years old. This —

27

HISTORY OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES

human skull cap was discovered by Dr. Robert B. Fox, American;

anthropologist of the National Museum, inside Tabon Cave}

Palawan, on eee 28, 1962. This human relic was called the!

“Tabon Man”’.”

|

The Coming of the Negritos. Ages fies the ‘disappearanes

of the ‘(Dawn Man”, the Negritos from the Asian mainlanc}

peopled the Philippines. They came about 25,000 years ago|

walking dry-shod through Malay Peninsula. Borneo, and the!

land bridges. Centuries after their arrival, the huge glaciers 0j/

ice melted and the increased volume of water raised the leve/

of the seas and submerged the land bridges. The Philippines was}

thus cut off from the Asian mainland. The Negritos lived perma:}

nently in the archipelago and became the first inhabitants.

;

The Negritos are among the smallest peoples on earth. They}

are below five feet in height, with black skin, dark kinky hair.}

round black eyes, and flat noses. Because of their black coloi|

and short stature, they were called Negritos (little black people)|

by the Spanish colonizers. In the Philippines they are known as|

Aeta, Ati, or Ita.

The Negritos were a primitive people with a culture belong.|

ing to the Old Stone Age (Paleolithic). They had no permanenii

settlements. They wandered in the forests and lived by hunting,

fishing, and gathering wild fruits and roots. Their homes were

temporary sheds made of jungle leaves and branches of trees.}

They wore little clothing. They had no community life, hence!

they developed no government,

writing, literature, arts, anc!

sciences. They possessed the crudest kind of religion which was

a belief in fetishes. They made fire by rubbing two dry sticks!

together to give them warmth. They had no pottery and nevei|

cooked their food. However, they were among the world’s bes!

archers, being skilled in the use of the bow and arrow.

|

The

Indonesians,

First Sea-Immigrants.

After

the sub- |

mergence of the land bridges, another Asian people migratec!

to the Philippines. They were the maritime Indonesians, whc!

belonged to the Mongoloid race with Caucasian affinities. “They!

. came in boats, being the first immigrants to reach the Philippines;

by sea. Unlike the Negritos, they were a tall people, with height!

ranging from 5 feet 6 inches to 6 feet 2 inches.

It is said. that two waves of Indonesian migration reachec

the PAUUPPUGR: The first wave came about 3000 B.C.; the secon¢

28

4

The Dawn

of Philippine History

wave about 1000 B.C. The Indonesians who came ‘in the first

migratory wave were tall in stature, slender in physique, and

light in complexion. Those in the second migratory wave were

shorter in height, bulkier in body, and darker in color.

The Indonesian culture was more advanced than that of the

Negritos. it belonged to the New Stone Age (Neolithic). The

Indonesians lived in grass-covered homes with wooden frames,

built above the ground or on top of trees. They. practised dry

agriculture and raised upland rice, taro (gabi), and other food

crops. Their clothing was made from beaten bark and decorated

with fine designs. They cooked their food in bamboo tubes, for

they knew nothing of pottery. Their other occupations were

hunting and fishing. Their implements consisted of polished stone

axes, adzes, and chisels. For weapons, they had bows and arrows,

spears, shields, and blowguns (sumpit). ae had one domesticated animal — the dog.

Exodus of the Malays to the Pacific World. The seafaring

Malays also navigated the vast stretches of the uncharted Pacific,

discovering and colonizing new islands, as far north as Korea

and southern Japan, as far east as Polynesia, and as far south

as Africa and Madagascar. Their unchronicled and unsung

maritime exploits impressed the British Orientalist A.R. Cowen,

who wrote:

““The Malays indeed were the Phoenicians of the

East, and apparently made even longer hauls than the Semitic

mariners, their oceanic elbowroom giving them more scope than

the coasts of the Mediterranean and the Red Sea.”?

The prehistoric Malays were the first discoverers and colonizers of the Pacific world. Long before the time of Columbus and

Magellan, they were already expert navigators. Although they

had no compass

and other nautical devices, they made long

- voyages, steering their sailboats by the position of the stars at

night and by the direction of the sea winds by day.

Malayan Immigration to the Philippines. In the course of

their exodus to the Pacific world, the ancient Malays reached

the Philippines. They came in three main migratory waves. The

first wave came from 200 B.C. to 100 A.D. The Malays who

came in this wave were the headhunting Malays, the ancestors

of the Bontoks, Ilongots, Kalingas, and other headhunting tribes