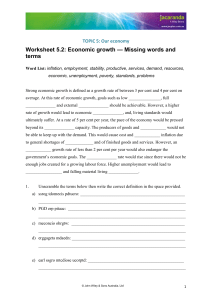

Starting a Business in the UK: A Practical Guide

advertisement