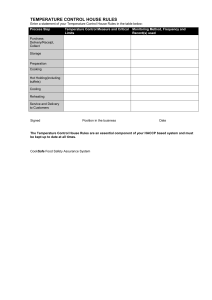

Not every recipe is made equal. Some recipes are missing ingredients, have improper spices, have low or bad directions, and a few are just untested. A standardized instruction could be a set of written instructions for preparing a known quantity and quality of food for a certain place. Even if UN agency follows the directions, a typical instruction can produce a product that is nearly comparable in style and yield when it is manufactured. The following are examples of good standardized instruction: Menu item name - the name of the specified instruction, which should match the menu item name. Total Yield - the number of servings or parts that a recipe generates, rather than the whole weight or volume of the recipe. Portion size refers to the quantity or size of a single serving. Ingredient list/quantity — each ingredient's exact quantity (with the exception of spices that will be superimposed to taste) Procedures for preparation - detailed instructions for the order and types of activities (e.g., blend, fold, mix, sauté). Temperatures and times of cooking, as well as HACCP key management points and restrictions, are all used to ensure that the meal is poached correctly and safely. Special instructions, in accordance with the quality format used in associate operation Mise nut place - a stockpile of small instruments and individual ingredient preparation Directions for serving as well as hot/cold storage Plating/garnishing Aside from the items listed above, standardized instructions may also include the following: recipe pricing, nutritional analysis, modifications, garnishing and presentation ideas, work simplification tips, recommended accompaniments or companion dishes, and photographs. It will be easier to simplify work and incorporate HACCP into operations if you standardize recipes. Several facilities that prepare food in large volumes batch cook so that standardized recipes can include such procedures in the guidelines. When creating instruction procedures or directions, the level of talent of the employees should also be considered. If more suitable for a particular activity, terminology within standardized recipes should be at the skill level of staff, for example, direct associate worker to soften butter and whisk with flour rather than oral communication "create a roux." Finally, the ability is modified for changes in state instrumentality, temperatures, and time. Employees will gather everything they need before commencing lesson preparation, decreasing time spent going around the room, room congestion, loss of focus due to frequent starting and stopping, and errors due to disruptions to their work. The clarity and efficacy of instruction preparation can also be improved by describing the mise nut place for particular items, such as peeling and cutting. Example: 12 in. diced raw white potato, peeled Some factors to keep in mind when drafting a standard recipe: If you're going to start with a home/internet tutorial, make it first! Standardized recipes can be used as a training tool for employees. A good instruction is similar to a well-crafted formula in that it has been tried and proven to work. S.A.M.E. stands for "Standardization Always Meets Expectations." As an effect, recipes Tool - For food service managers and operations, standardized recipes are a critical management tool. A regular instruction ensures not only consistent quality and quantity, but also a steady price range. It is critical that the value of each instruction and piece be computed and compared consistently in order for an operation to line a menu asking price that allows the operation to make a profit. The following are some of the advantages of using standardized instruction: a consistent level of quality and quantity standard portion size and price ensuring nutritional value and dealing with dietary difficulties such as special diets and food allergies assisting in ensuring compliance with the "Truth in Menu" requirements assisting in forecasting and purchasing Food orders are less likely to be incorrect. combining ideas of work simplification and cross-training aids assisting in the training of new employees HACCP concepts are being implemented. waste reduction just meeting customer expectations The following are some of the most common arguments against standardized recipes: take a long time to utilize Employees dislike them, and they have the foresight to try to do things in the institution. The chef does not want to divulge his or her trade secrets. take an excessive amount of time to write/develop Although these arguments against using standardized recipes are valid in some instances, a successful foodservice manager understands that they cannot prevent a company from establishing and consistently using standardized recipes. This crucial observation is crucial to our profitability. At the very least, our clients should expect a similar nutritional quality and matter content, but they should also expect an equivalent product when they order a menu item they like and appreciate. IN THE ROOM, THE TYPES OF MEASUREMENTS USED Within the edifice trade, there are three types of measures used to measure ingredients and serve parts. Volume, weight, and count are all methods of measurement. All three types of measuring could be used in a recipe. Three eggs (measured by count), eight ounces of milk (measured by volume), and one pound of cheese are examples of directions (measurement by weight). There are both statutory and informal regulations that control which type of measurement should be employed. There are also protocols in place to ensure that the task is conducted correctly and in a systematic manner. Count or number When accurate measuring isn't necessary and the items to be utilized are recognized to be march on size, number measuring is rarely used. Volume - When it comes to liquids or fluids, volume measurement is sometimes utilized because they are difficult to weigh. It's also used for dry ingredients in home cooking, but it's less commonly used in the trade for dry measuring. When it comes to portioning sizes of completed products, volume is frequently used. To keep serving sizes constant, portion scoops are commonly used to measure out veggies, salads, and sandwich ingredients. Soups and sauces are usually served with precise-sized ladles. Scoops and ladles for portioning are commonly sized by variety. Such variability on a scoop refers to the number of full scoops necessary to fill a 1 quart capacity. Spoodles and ladles are measured in ounces. Weight Because of live components or parts, weight is the most accurate. When ingredient proportions are crucial, their measurements are always expressed in weights. This is especially true in baking, where it's typical to list all components, including eggs, by weight (which, as mentioned earlier, in most alternative applications ar immersed by count). Whether it's solids or liquids, activity by weight is a lot more constant and predictable. Weighing takes a little longer and requires the use of scales, but it pays off in terms of precision. Digital portion scales are most commonly used in trade and come in a variety of sizes to accommodate weights up to eleven pounds. For many recipes, this is usually sufficient, while larger operations may require scales with greater capacity. The reason weight is more accurate than volume is that it takes into account elements like density, moisture, and temperature, all of which can affect the quantity of materials. One cup of refined sugar (measured by volume) could change dramatically depending on whether it's packed loosely or securely within the vessel. On the other hand, 10 ounces of refined sugar will always be ten ounces. Even flour, which one might assume is fairly consistent, can vary from location to location, requiring an adjustment in the amount of liquid required to get a similar consistency when mixed with a certain volume. Another typical blunder is conflating the terms volume and weight. Water is the only element that has a consistent volume and weight: one cup water = eight ounces water. Because of gravity and the density of Associate in Nursing item, there is no substitute ingredient that can be measured interchangeably. Each ingredient has a completely different density and attraction weight, which might vary depending on the area. This is commonly referred to as relative density. The relative density of water is one. 0. Liquids that are lighter than water (for example, oils that float on water) have a specific gravity of one. 0. Those that are heavier than water and sink, such as syrup, have a gravity greater than one. 0. Keep in mind that you should not substitute a volume live for a weight live, and vice versa. 5 Points to Consider in Hazard Analysis and Management The HACCP system is made up of seven processes that are used to manage risks and are called after the HACCP principles: 1.Conduct hazard analysis: The first stage in developing a HACCP strategy is to conduct a hazard analysis. Its goal is to compile a list of dangers that are reasonably likely to result in injury or illness if not appropriately controlled. If a risk is seen as unlikely to occur, it will be managed through a requirement program, such as smart manufacturing Practices or SSOP. 2.Determine important management points (CCPs): CCPs are the points in the food processing where hazards are frequently avoided, removed, or lowered to acceptable levels. 3.Establishment of important limits: crucial limits are the characteristics that show whether the CCP's management measure is in or out of management. It is a maximum or lowest price at which a biological, chemical, or physical parameter should be managed in order to prevent, eliminate, or reduce a parameter to an acceptable level. 4.Develop a watching procedure: this is usually a collection of observations or measures to determine whether or not a CCP is in restraint and to give an accurate record for future verification. Each CCP in the HACCP plan should be monitored to ensure that the critical limits are consistently fulfilled and that the method is producing a safe product. 5.Determine corrective actions and preventive measures: In circumstances where the critical limit is not met, corrective actions should be developed for each CCP. Corrective efforts are required to prevent potentially hazardous foods from reaching consumers. The corrective actions are as follows: a. Identifying and removing the cause of the deviation, b.Assuring that the CCP is restrained while the corrective action is implemented, c.Making certain that steps are in place to prevent a repeat, and d.Making certain that no product with the variation is shipped. 6.Develop procedures for record-keeping and documentation: All measurements obtained at a CCP, as well as any corrective actions done, should be documented and kept on file indefinitely. These data are frequently used to track a finished product's assembly history. A study of records is used to determine if the product was prepared in an extremely safe manner in accordance with the HACCP plan. 7.Develop verification procedures: The verification of the establishment's HACCP system entails four steps. The institution is responsible for the first three, while FSIS is responsible for the fourth. a.Validation methods, which determine whether or not the CCP and related critical limits are acceptable and sufficient to handle hazards that are reasonably likely to arise. b.To ensure that the entire HACCP system runs properly, at first Associate in Nursingd on a daily basis. c.Reappraise the HACCP plan on a regular basis, as documented. d.Government verification (under the administrative unit assigned to FSIS) to ensure that the establishment's HACCP system is in good working order.