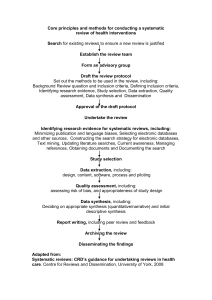

Systematic Literature Review Guidance in Planning Research

advertisement