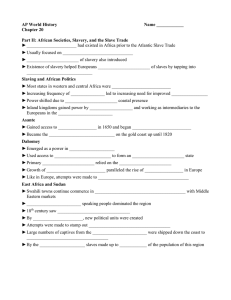

Africa And The Africans In The Age Of The Atlantic Slave Trade Various Authors Edited By: R. A. Guisepi African Societies, Slavery, And The Slave Trade Europeans in the age of the slave trade sometimes justified enslavement of Africans by pointing out that slavery already existed on that continent. However, while forms of bondage were ancient in Africa, and the Muslim trans­Saharan and Red Sea trades were long­standing, the Atlantic trade interacted with and transformed these earlier aspects of slavery. African societies had developed many forms of bondage and servitude that varied from a kind of peasant status to something much more like chattel slavery in which people are considered things ­ "property with a soul," as Aristotle put it. African states were usually nonegalitarian and since in many African societies all land was owned by the state or the "ruler," the control of slaves was one of the few, if not the only way, in which individuals or lineages could increase their wealth and status. Slaves were employed in many ways as servants, concubines, soldiers, administrators, and field workers. In some cases, as in the ancient empire of Ghana and in Kongo, there were whole villages of enslaved dependents who were required to pay tribute to the ruler. The Muslim traders of West Africa who linked the forest region to the savanna had slave porters as well as villages of slaves to supply their caravans. In a number of situations, these forms of servitude were relatively benign and were an extension of lineage and kinship systems. In others, however, they were exploitative economic and social relations that reinforced the hierarchies of various African societies and allowed the nobles, senior lineages, and rulers to exercise their power. Among the forest states of West Africa, such as Benin, and in the Kongo kingdom in central Africa slavery was already an important institution prior to the European arrival, but the Atlantic trade opened up new opportunities for expansion and intensification of slavery in those societies. Despite considerable variation in African societies and the fact that slaves sometimes attained positions of command and trust, in most cases slaves were denied choice about their lives and actions. They were placed in dependent or inferior positions, and they were often considered aliens. It is important to remember that the enslavement of women was a central feature of African slavery. Although slaves were used in many ways in African societies, domestic slavery and extension of lineages through the addition of female members remained a central feature in many places. Some historians believe that the excess of women led to polygyny and the creation of large harems by rulers and merchants, whose power was increased by this process while the position of women was lowered in some societies. In the Sudanic states of the savanna, Islamic concepts of slavery had been introduced. Slavery was viewed as a legitimate fate for nonbelievers but an illegal treatment for Muslims. Despite the complaints of legal scholars like the Ahmad Baba of Timbuktu (1556­1627) against the enslavement of Muslims, many of the Sudanic states enslaved their captives both pagan and Muslim. In the Niger Valley many slave communities produced agricultural surpluses for the rulers and nobles of Songhay, Gao, and other states. Slaves were used for gold mining and salt production, and as caravan workers in the Sahara. Slavery was a widely diffused form of labor control and wealth in Africa. The existence of slavery in Africa and the preexisting trade in people allowed Europeans to mobilize the commerce in slaves relatively quickly by tapping existing routes and supplies. In this venture they were aided by the rulers of certain African states who were anxious to acquire more slaves for themselves and to supply slaves to the Europeans in exchange for aid and commodities. In the 16th century Kongo kingdom, the ruler had an army of 20,000 slaves as part of his household, and this gave him greater power than any Kongo ruler had ever held. In general, African rulers did not enslave their own people, except for crimes or in other unusual circumstances, but rather sought to enslave their neighbors. Thus, expanding, centralizing states were often the major suppliers of slaves to the Europeans as well as to societies in which slavery was an important institution. Slaving And African Politics As one French agent put it, "the trade in slaves is the business of kings, rich men, and prime merchants." European merchants and royal officials were able to tap existing routes, markets, and institutions, but the new and constant demand also intensified enslavement in Africa and perhaps changed the nature of slavery itself in some African societies. In the period between 1500 and 1750 as the gunpowder empires and expanding international commerce of Europe penetrated sub­Saharan Africa, existing states and societies were often transformed. Although, as we saw in Chapter 14, the empire of Songhay controlled a vast region of the western savanna until its defeat by a Moroccan invasion in 1591, for the most part the many states of central and western Africa were relatively small and fragmented. This led to a situation of instability caused by competition and warfare as states sought to expand at the expense of their neighbors or to consolidate power by incorporating subject provinces. The warrior or soldier emerged in this situation as an important social type in states such as the Kongo kingdom and Dahomey, as well as along the Zambezi River. The incessant wars promoted the importance of the military and made the sale of captives into the slave trade an extension of the politics of regions of Africa. Sometimes, as among the Muslim states of the savanna or the Lake Chad region, wars took on a religious overtone of believers against nonbelievers, but in much of West and central Africa that was not the case. Some authors see this situation as an endemic aspect of African politics; others feel it is the result of European demand for new slaves. In either case, the result was the capture and sale of millions of human beings. While increasing centralization and hierarchy could be seen in the enslaving African societies, a contrary trend of self­sufficiency and antiauthoritarian ideas developed among those peoples who bore the brunt of the slaving attacks. One result of the presence of Europeans on the coast was a shift in the locus of power within Africa. Whereas states like Ghana and Songhay in the savanna had taken advantage of their position as intermediaries between the gold of the West African forests and the trans­Saharan trade routes, now those states closer to the coast or in contact with the Europeans could play a similar role. Those right on the coast tried to monopolize the trade with Europeans, but European meddling in their internal affairs and European fears of any coastal power that became too strong blocked the creation of centralized states under the shadow of European forts. Just beyond the coast it was different. With access to European goods, especially firearms, iron, horses, cloth, tobacco, and other goods, West and central African kingdoms began to redirect trade toward the coast and to expand their influence. Some historians have written of a gun and slave cycle in which increased firepower allowed these states to expand over their neighbors, producing more slaves that then could be exchanged for more guns. The result was unending warfare and the disruption of societies as the search for slaves pushed ever farther into the interior. Asante And Dahomey Perhaps the effects of the slave trade on African societies are best seen in some specific cases. A number of large states developed in West Africa during the slave trade era. Each, in its own way, represented a response to the realities of the European presence and to the process of state formation long under way in Africa. Rulers in these states grew in power and often surrounded themselves with ritual authority and a luxurious court life as a way of reinforcing the position that their armies had won. In the area called the Gold Coast by the Europeans, the empire of Asante (Ashanti) rose to prominence in the period of the slave trade. The Asante were members of the Akan people (the major group of modern Ghana) who had settled in and around Kumasi, a region of gold and kola nut production that lay between the coast and the Hausa and Mande trading centers to the north. There were at least 20 small states based on the matrilineal clans that were common to all the Akan peoples, but those of the Oyoko clan predominated. Their cooperation and their access to firearms after 1650 initiated a period of centralization and expansion. Under the vigorous Osei Tutu (d. 1717) the title of asantehene was created as supreme civil and religious leader. His golden stool became the symbol of an Asante union that was created by linking the many Akan clans under the authority of the asantehene but rec­ ognizing the autonomy of subordinate areas. An all­Asante council advised the ruler, and an ideology of unity was was used to overcome the traditional clan divisions. With this new structure and a series of military reforms, conquest of the area began. By 1700 the Dutch on the coast realized that a new power had emerged, and they began to deal directly with it. With control of the gold­producing zones and a constant supply of prisoners to be sold as slaves for more firearms, Asante maintained its power until the 1820s as the dominant state of the Gold Coast. Although gold hontinued to be a major item of export, by the end of the 17th century the value of slaves made up almost two­thirds of Asante's trade. Farther to the east in the area of the Bight of Benin (between the Volta and Benin rivers on what the Europeans called the Slave Coast), a number of large states developed in the slave trade era. The kingdom of Benin was at the height of its power when the Europeans arrived. It traced its origins to the city of Ife and to the Yoruba peoples that were its neighbors, but it had become a separate and independent kingdom with its own well­developed political and artistic traditions, especially in the casting of bronze. As early as 1516 the ruler, or oba, limited the slave trade from Benin, and for a long time most of the trade with Europeans was controlled directly by the king and was in pepper, textiles, and ivory rather than slaves. Eventually European pressure and the goals of the Benin nobility combined to generate a significant slave trade in the 18th century, but Benin never made the slave trade its primary source of revenue or state policy. The kingdom of Dahomey, which developed among the Fon (or Aja) peoples, used a different strategy of response to the European presence. It began to emerge as a power in the 17th century from its center at Abomey about 70 miles from the coast. Its kings ruled with the advice of councils that had considerable power, but by the 1720s access to firearms allowed the rulers to create an autocratic and sometimes brutal political regime based on the slave trade. In the 1720s, under king Agaja (1708­1740), the kingdom of Dahomey moved toward the coast, seizing in 1727 the port town of Whydah, which had attracted a large number of European traders. Although Dahomey became to some extent a subject of the powerful neighboring Yoruba state of Oyo, whose cavalry and archers made it strong, Dahomey maintained its autonomy and turned increasingly to the cycle of firearms and slaves. The trade was controlled by the royal court, whose armies (including a regiment of women) were used to raid for more captives. As Dahomey expanded it eliminated the royal families and customs of the areas it conquered and imposed its own traditions. This resulted in the formation of a unified state that proved more lasting than some of its neighbors. Well into the 19th century, Dahomey was a slaving state. Dependence on the trade in human beings had negative effects on the society as a whole. The large­scale sacrifice of human victims in the annual renewal festival, or Customs, at the royal court was one example of the cheapening of life that the trade produced. Historians argue about whether the expansion of Dahomey was driven by the desire for more slaves or by an attempt to unify all the Aja peoples, but in any case, slavery played a central role in the history of the area. Over 1.8 million slaves were exported from the Bight of Benin between 1640 and 1890. Emphasis on the slave trade should not obscure the creative process within many of the African states. The growing devine authority of the rulers paralleled in some ways the rise of absolutism in Europe. It led to the development of new political forms, some of which had the power to limit the role of the king. In the Yoruba state of Oyo, for example, a governing council shared power with the ruler. In some states, a balance of offices kept central power in check. In Asante the traditional village chiefs and officials whose authority was based on their lineage were increasingly challenged by new officials appointed by the asantehene, as a state bureaucracy began to form. The creativity of these societies was also seen in traditional arts. In many places, crafts such as bronze casting, woodcarving, and weaving flourished. Guilds of artisans developed in a number of societies and their specialization produced crafts executed with great skill. In Benin and the Yoruba states, for example, remarkable and lifelike sculptures in wood and ivory continued to be produced. Often, however, the best artisans labored for the royal court, producing objects designed to honor the ruling family and reinforce the civil and religious authority of the king. This was true in architecture, weaving, and the decorative arts as well. Much of this artistic production also had a religious function or contained religious symbolism as African artists made the spiritual world visually apparent. East Africa And The Sudan West Africa was obviously the region most directly influenced by the trans­Atlantic slave trade, but there and elsewhere in Africa, long­term patterns of society and economy continued and intersected with the new external influences. On the East Coast of Africa, the Swahili trading cities continued their commerce in the Indian Ocean and the Arabian Sea, accommodating to the military presence of the Portuguese and the Ottoman Turks. Trade to the interior continued to bring ivory, gold, and a steady supply of slaves. Many of these slaves were destined for the harems and households of Arabia and the Middle East, but also a small percent were carried away by the Europeans for their plantation colonies. The Portuguese and Indo­Portuguese settlers along the Zambezi River in Mozambique made use of slave soldiers to increase their territories, and certain groups in interior East Africa specialized in supplying ivory and slaves to the East African coast. Europeans did establish some plantation­style colonies on islands like Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, and these depended on the East African slave trade. On Zanzibar and other offshore islands, and later on the coast itself, Swahili, Indian, and Arabian merchants actually followed the European model and set up plantations producing cloves, using African slave laborers. Some of the plantations were large, and by the 1860s Zanzibar had a slave population of around 100,000. The sultan of Zanzibar alone owned over 4000 slaves in 1870. Slavery became an extensive feature of the East African coast, and the slave trade from the interior to these plantations and to the traditional slave markets of the Red Sea continued until the end of the 19th century. Much less is known about the interior of eastern Africa. The well­watered and heavily populated region of the great lakes of the interior supported large and small kingdoms. Bantu­speakers predominated but a number of peoples inhabited the region. Linguistic and archeological evidence suggests that pastoralist Nilotic peoples from the Upper Nile Valley with a distinctive late iron age technology had moved southward into what is today western Kenya and Uganda where they came into contact with Bantu­speakers and with the farmers and herdsmen who were speakers of another group of languages called Cushitic. The Bantu states absorbed the immigrants, even when at times the newcomers established ruling dynasties. Later Nilotic migrations, especially of the Luo peoples, resulted in the construction of a number of related dynasties among the states in the area of the large lakes of east­central Africa. At Bunyoro, the Luo eventually established a ruling dynasty among the existing Bantu population. This composite kingdom exercised considerable power in the 16th and 17th centuries. Other related and similar states formed in the region. In Buganda, near Lake Victoria, a strong monarchy ruled a heterogeneous population and dominated the region in the 18th century. These developments in the interior, as important as they were for the history of the region, were less influenced by the growing contact with the outside world than were other regions of Africa. Across the continent in the northern savanna at the end of the 18th century, the process of Islamization, which had been important in the days of the empires of Mali and Songhay, entered a new and violent stage that not only linked Islamization to both the external slave trades and the growth of slavery in Africa, but also produced other long­term effects in the region. After the break up of Songhay in the 16th century, a number of successor states had developed. Some, such as the Bambara kingdom of Segu, were pagan. Others, such as the Hausa kingdoms in Northern Nigeria, were ruled by Muslim royal families and urban aristocracies but continued to contain large numbers of animist subjects, most of whom were rural peasants. In these states the degree of Islamization was slight, and an accommodation between Muslims and animists was achieved. Beginning in the 1770s Muslim reform movements began to sweep the western Sudan. Religious brotherhoods advocating a purifying Sufi variant of Islam extended their influence throughout the Muslim trade networks in the Senegambia region and the western Sudan. This movement had an intense impact on the Fulani (Fulbe), a pastoral people who were spread across a broad area of the western Sudan. In 1804 Usuman Dan Fodio, a studious and charismatic Muslim Fulani scholar, began to preach the reformist ideology in the Hausa kingdoms. His movement became a revolution when in 1804, seeing himself as God's instrument, he preached a jihad against the Hausa kings whom he felt were not following the teachings of the Prophet. A great upheaval followed in which the Fulani took control of most of the Hausa states of northern Nigeria in the western Sudan. A new kingdom, based on the city of Sokoto, developed under Dan Fodio's son and brother. The Fulani expansion was driven not only by religious zeal but by political ambitions, as the attack on the well­established Muslim kingdom of Bornu demonstrated. The result of this upheaval was the creation of a powerful Sokoto state under a caliph, whose authority was established over cities such as Kano and Zaria and whose rulers became emirs of provinces within the Sokoto caliphate. By the 1840s the effects of Islamization and the Fulani expansion were felt across much of the interior of West Africa. New political units were created, a reformist Islam that sought to eliminate pagan practices was spread, and social and cultural changes took place in the wake of these changes. Literacy, for example, became more widely dispersed and new centers of trade, such as Kano, emerged in this period. Later jihads established other new states along similar lines. All of these changes had long­term effects on the region of the western Sudan. These upheavals ­ moved by religious, political, and economic motives ­ were not unaffected by the external pressures on Africa. They fed into the ongoing processes of the external slave trades and the development of slavery within African societies. Large numbers of captives resulting from the wars were exported down to the coast for sale to the Europeans, while another stream of slaves crossed the Sahara to North Africa. In the western and central Sudan the level of slave labor rose, especially in the larger towns and along the trade routes. Slave villages, supplying royal courts and merchant activities as well as a sort of plantation system, developed to produce peanuts and other crops. Slave women spun cotton and wove cloth for sale, slave artisans worked in the towns, and slaves served the caravan traders, but most slaves did agricultural labor. By the late 19th century regions of the savanna contained large slave populations ­ in some places as much as 30 to 50 percent of the whole population. From the Senegambia region of Futa Jallon, across the Niger and Senegal basins, and to the east of Lake Chad, slavery became a central feature of the Sudanic states and remained so through the 19th century. White Settlers And Africans In Southern Africa One area of Africa little affected by the slave trade in the early modern period was the southern end of the continent. This region was still occupied by non­Bantu hunting peoples, the San (Bushmen), and by the Khoikhoi (Hottentots) who lived by hunting and sheep herding, and, after contact with the Bantu, cattle­herding peoples as well. Peoples practicing farming and using iron tools were living south of the Limpopo River by the 3d century a.d. Probably Bantu­speakers, they spread southward and established their villages and cattle herds in the fertile lands along the eastern coast, where rainfall was favorable to their agricultural and pastoral way of life. The drier western regions toward the Kalahari Desert were left to the Khoikhoi and San. Mixed farming and pastoralism spread throughout the region in a complex process that involved migration, peaceful contacts, and warfare. By the 16th century, Bantu­speaking peoples occupied much of the eastern regions of southern Africa. They practiced agriculture and herding; worked iron and copper into tools, weapons, and adornments; and traded with their neighbors. They spoke related languages such as Tswana, Sotho, as well as the Nguni languages such as Zulu and Xhosa. Among the Sotho, villages might have contained as many as 200 people, but the Nguni lived in hamlets made up of a few extended families. Men served as artisans and herdsmen; women did the farming and housework, and sometimes organized their labor communally. Politically, chiefdoms of various sizes ­ many small, but a few with as many as 50,000 inhabitants ­ characterized the southern Bantu peoples. Chiefs held power with the support of relatives and with the acceptance of the people, but there was considerable variation in chiefly authority. The Bantu­speaking peoples' pattern of political organization and the splitting off of junior lineages to form new villages created a process of expansion that led to competition for land and absorption of newly conquered groups. This situation became intense at the end of the 18th century, either because of the pressures and competition for foreign trade through the Portuguese outposts on the East African coast or because of the growth of population among the southern Bantu. In any case, the result was farther expansion southward into the path of another people who had arrived in southern Africa. In 1652 the Dutch East India Company established a colony at the Cape of Good Hope to serve as a provisioning ground for ships sailing to Asia. On the fertile lands around this colony relatively large farms developed. The Cape colony depended on slave labor brought from Indonesia and Asia for a while, but it soon enslaved local Africans as well. The expanding colony and its labor needs led to a series of wars with the San and Hottentot populations, who were pushed farther to the north and west. By the 1760s the Dutch, or Boer, farmers had crossed the Orange River in search of new lands. They viewed the fertile plains and hills as theirs, and they saw the Africans only as intruders and as a possible source of labor. Competition and warfare resulted. Around 1800 the Cape colony had about 17,000 settlers (or Afrikaners as they came to be called), 26,000 slaves, and 14,000 Khoikhoi. At the same time that the Boers were pushing northward, the southern Bantu were extending their movement to the south. Matters were also complicated by European events when Great Britain seized the Cape colony in 1795 and then took it under formal British control in 1815. While the British government helped the settlers to clear out Africans from potential farming lands, government attempts to limit the Boer settlements and their use of African labor were unsuccessful. Meanwhile competition for farming and grazing land led to a series of wars between the settlers and the Bantu during the early 19th century. Various government measures, the increasing arrival of English­speaking immigrants, and the lure of better lands caused groups of Boers to move to the north. These "voortrekkers" moved into lands occupied by the southern Nguni, eventually creating a number of autonomous Boer states. After 1834, when Britain abolished slavery and imposed restrictions on landholding, groups of Boers staged a "great trek" far to the north to be free of government interference. This movement eventually brought them across the Orange River and into Natal on the more fertile east coast, which the Boers believed to be only sparsely inhabited by Africans. They did not realize at the time that the lack of population was due to a great military upheaval taking place among the Bantu peoples of the region. The "Mfecane" And The Zulu Rise To Power Among the Nguni peoples, major changes had taken place. A process of unification had begun among some of the northern chiefdoms, and a new military organization had emerged. In 1818 leadership fell to Shaka, a brilliant military tactician who reformed the loose forces into regiments organized by lineage and age. Iron discipline and new tactics were introduced, including the use of a short stabbing­spear to be used at close range. The army was made a permanent institution, and the regiments were housed together in separate villages. The fighting men were only allowed to marry after their service had been completed. Shaka's own Zulu chiefdom became the center of this new military and political organization that began to absorb or destroy its neighbors. Shaka demonstrated considerable talents as a politician, destroying the ruling families of those groups he incorporated into the growing Zulu state. He ruled with an iron hand, destroying his enemies, acquiring their cattle, and crushing any opposition. His policies brought power to the Zulu, but his erratic and cruel behavior also earned him enemies among his own people. Though he was assassinated in 1828, Shaka's reforms remained in place and his successors built on the structure he had created. Zulu power was still growing in the 1840s, and the Zulu remained the most impressive military force in black Africa until the end of the century. The rise of the Zulu and other Nguni chiefdoms was the beginning of the mfecane, or wars of crushing and wandering. As Zulu control expanded, a series of campaigns and forced migrations led to incessant fighting, as other peoples sought to survive by fleeing, emulating, or joining the Zulu. Groups spun off to the north and south, raiding the Portuguese on the coast, clashing with the Europeans to the south, and fighting with neighboring chiefdoms. New African states, such as the Swazi, that adapted aspects of the Zulu model emerged among the survivors. One state, Lesotho, successfully resisted the Zulu example. It combined Sotho and Nguni speakers and defended itself against Nguni armies. It eventually developed as a kingdom far less committed to military organization and one in which the people exercised considerable influence on their leaders. The whole of the southern continent, from the Cape colony to Lake Malawi, had been thrown into turmoil by raiding parties, remnants, and refugees. Superior firepower allowed the Boers to continue to hold their lands, but it was not until the Zulu Wars of the 1870s that Zulu power was crushed by Great Britain ­ and even then only at great cost. During the process, the basic patterns of conflict between Africans and Europeans in the largest settler colony on the continent were created. These patterns included a competition between settlers and Africans for land, the expanding influence of European governmental control, and the desire of Europeans to make use of Africans as laborers