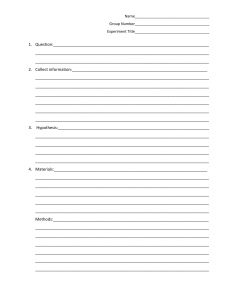

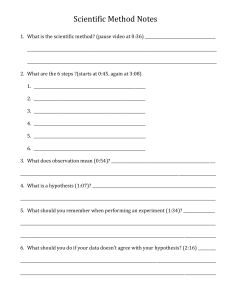

Ms. Desirée Moffitt Scientific Method Lab Using the Scientific Method Introduction The purpose of this lab is to introduce you to the scientific method and the process of scientific inquiry. This lab will require you to collect data, display your data in histogram form, and provide an interpretation of your findings. You must fill out the entire lab sheet and upload it under Lab 1 in your course. You must answer all questions and use complete sentences for full credit. Read this entire document prior to answering questions embedded within! The Process of Scientific Investigation: Doing Science Broadly put, science is a process. It allows trained individuals to derive meaningful information about the world. Scientists gain this information by making observations, asking questions about those observations, formulating a testable hypothesis (a proposed explanation for their observations and the question they are investigating), collecting data, interpreting the data, and then publishing their findings. An important part of this process is understanding that the data that a scientist collects may or may not support their hypothesis. Whether a hypothesis is supported or not, it is still valuable information and it is important to provide those results to the scientific community. Below is an example of data that did not support a hypothesis. I studied salamander populations and distributions for two years. During this time, I observed (noticed) declines in their numbers. I had read multiple scientific papers about a fungus that was affecting salamander populations. This fungus hindered the salamanders’ ability to exchange gasses with their environment. The fungus was essentially suffocating infected amphibians because it hardened their skin to the point of hindering their ability to release carbon dioxide into their environment and pick-up oxygen. Through my investigation of the scientific literature, I discovered that no one had looked for this fungus in the location I was studying. This made me ask: is this fungus present and causing declines in salamander populations in my study region? From there, I formulated a testable hypothesis: salamander populations are declining due to infection with this fungus. In order to test my hypothesis, I needed to collect data. I collected DNA samples from 200 salamanders in my study area. I then analyzed that DNA to determine if the fungus was “present” or “not present” in each of the 200 salamanders. What I found was that the fungus was NOT present in any of the 200 salamanders. This did not support my hypothesis. However, I still published my findings. Why? Because it is information that contributes to the understanding of a problem (declining amphibian populations and the distribution of that fungus). By publishing my results, the information that I found is now available to other scientists. If another scientist wants to investigate why salamander populations are declining in that same region, they can read and 1 Ms. Desirée Moffitt Scientific Method Lab scrutinize my paper and determine an appropriate next step, which may actually include redoing what I had done! Checks and balances… Assignment Overview For part one of your lab, we are going to learn more about what the scientific method looks like. We will observe, ask questions, and formulate hypotheses. For part two of your lab, we will collect our own data, organize it in a table, and then put it into graph form. We are going to specifically explore the handspan of your classmates (and anyone else we need in order to reach 10 individual handspans). Part I Scientific Method: Making Observations and Asking Questions 1. Observations lead to questions! Let’s think about handspan. List two observations you have made about handspan. Have you noticed a relationship between handspan and quality of handwriting? You may list any observation you have but if you intend on relating handspan to any anatomical structure, you must use appropriate anatomical terminology. And remember, observations are statements, not questions. 2. Next, ask two questions you have about those observations (one question per observation). Questions that follow observations lead to hypotheses. A question regarding the relationship between handspan and handwriting could be, “are larger handspans associated with less legible handwriting?”. Do not include any extra information. Observation 1 and Question 1 1. Typically the adult male handspan is larger than the adult female handspan. 2. Does the ratio of finger size to palm size differ between genders? Observation 2 and Question 2 1. Often those with smaller hands claim that their hands are colder than others. 2. Does handspan effect the external temperature of the hand in any way? 2 Ms. Desirée Moffitt Scientific Method Lab Part 1, Step 2: Developing a Hypothesis from the Question You Asked When writing your questions, you likely speculated what the answers were. When scientists pose an explanation to their question, that explanation is called a hypothesis. Follow this example: if I make the observation that smokers seem to have more cases of cancer, and follow that with the question “Is there a relationship between smoking cigarettes and instances of cancer?”, one reasonable hypothesis would be “Individuals who smoke 20 cigarettes per day are at a greater risk of cancer than those individuals who smoke 0 cigarettes per day”. • • • It is important to note that a hypothesis is not a question. It is a tentative, testable answer for the question you formed based on your observation. A hypothesis must be clear, concise, and testable. You can’t test “All elephants are grey” because you cannot physically examine all elephants. As stated earlier in the introduction, the results gained from testing a hypothesis can either support a hypothesis, or refute a hypothesis. Even if your hypothesis was unsupported, the information gained is still valuable. Using the two questions you posed in part 1, formulate one hypothesis for each. Remember a hypothesis must be testable (don’t use words like ‘all’, ‘always’, ‘never’…). Hypothesis 1 Despite males usually having a larger handspan overall, I predict that the ratio of finger size to palm size will be greater in females than in males. Hypothesis 2 I think that people with smaller handspans will have a lower external temperature than those with larger handspans. Part 2, Step 1: Data Collection We will now collect data on handspan. Refer to the discussion board in your course titled, “Class Data Exchange for Lab 1”. You don’t need to interact with your classmates. The purpose of this “discussion” is just to post your handspan (in cm) and collect your classmate’s handspan data. Using the table below, record the handspan of 10 people’s dominant hand. If we do not have 10 people in the course, you may request this information from friends and family. Feel free to post that data on the discussion board to help out your classmates! Be sure to calculate the average of your 10 handspans in the table. 3 Ms. Desirée Moffitt Scientific Method Lab For “size class” you will be categorizing each hand based on two cm intervals. The intervals are as follows: <12 cm, 12-14 cm, 14-16 cm, 16-18 cm, 18-20 cm, 20-22 cm, 22-24 cm, 24-26 cm, 26-28 cm, 28-30 cm, and >30 cm. You can write which of those categories the hand falls into. For example, my hand would fall into the 14-16 cm category. If you are confused about the cm 1 Hannah R 16.5 cm 16-18 cm 2 Brent R 21.5 cm 20-22 cm 3 Alex R 20 cm 18-20 cm 4 Brian R 16.5 cm 16-18 cm 5 Cherisse R 18.5 cm 18-20 cm 6 Allie R 17.8 cm 16-18 cm 7 Jasmine R 16 cm 14-16 cm 8 Steve R 17.5 cm 16-18 cm 9 Jordan R 20 cm 18-20 cm 10 Blake R 22.5 cm 22-24 cm 18.7 cm overlap between the categories (like, 12-14 cm and the next category 14-16 cm) think of it this way: 12.1-14.0 cm, 14.1-16.0 cm. 4 Ms. Desirée Moffitt Scientific Method Lab Part 2, Step 2: Creating a Histogram to Visualize our Data Next, we will construct a histogram. A histogram is a means to visualize your data based on frequency distributions. It’s similar to a bar graph/chart with some differences. Check out the image on the right that shows the differences between a histogram and bar graph/chart. A histogram shows “how many” per numeric category. If you have three people that fall into the 12-14 cm range, you would fill in the bar up to the number 3 on the Y axis (the vertical line on the histogram). Below is our histogram. 1. First, label your Y-axis. What goes there? 2. Next, create a title for the histogram (don’t just call it “Histogram”). 3. Fill in the histogram based on the number of individuals in each range. For example, if you had four different handspans fall within the 20-22 cm range, you would fill in four 5 Ms. Desirée Moffitt Scientific Method Lab boxes. Part 2, Step 3: Interpreting our Data Look at the histogram you filled out. What can you say about handspan based on this visualization of the data? Is there more or one range? Less than one range? Do you find there is a cluster in the middle? Don’t stop there! Make more interpretations. 6 Ms. Desirée Moffitt Scientific Method Lab Interpretation of Handspan based on Histogram Examination In my histogram, there are five ranges total based on the data I gathered. The range category with the most people in it is the 16-18 cm category with four people, followed second by the 18-20 cm category with three people. Lastly the 14-16, 20-22, and 22-24 cm categories all tied with only one person in each. There were no people that had handspans that fell into the smallest categories like <12 cm and 12-14 cm. Similarly, there were also none in any of the larger ranges above the 22-24 cm category. Be sure you wrote everything in complete sentences. Check your grammar. Make sure your assignment makes sense. Now, turn it in! 7