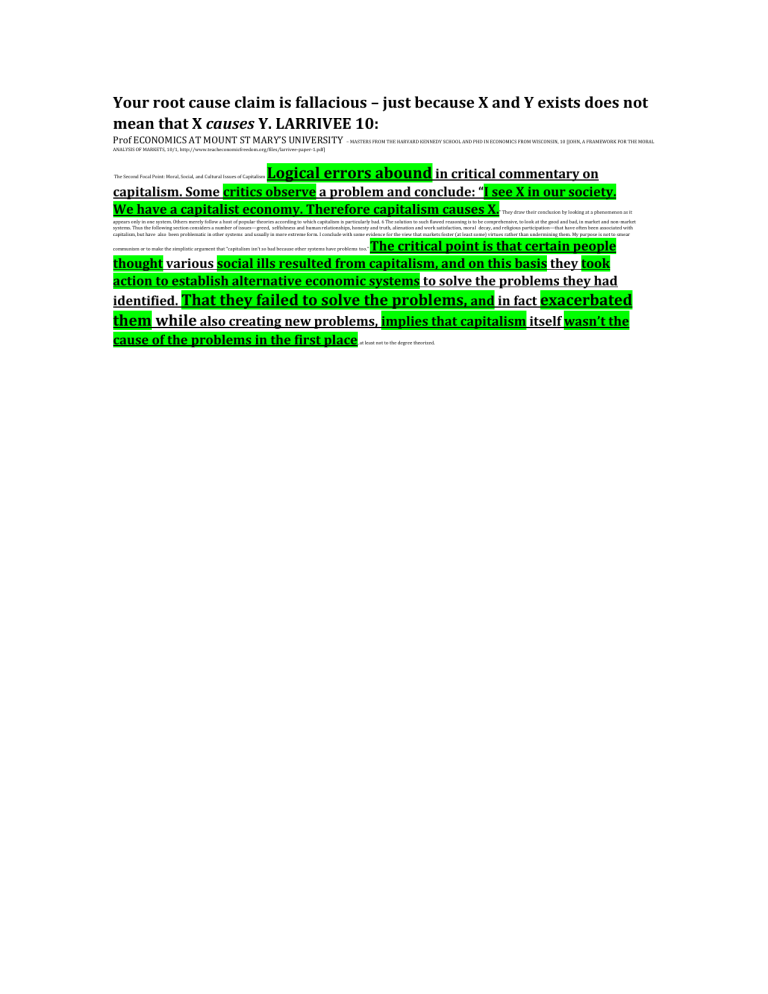

Your root cause claim is fallacious – just because X and Y exists does not mean that X causes Y. LARRIVEE 10: Prof ECONOMICS AT MOUNT ST MARY’S UNIVERSITY – MASTERS FROM THE HARVARD KENNEDY SCHOOL AND PHD IN ECONOMICS FROM WISCONSIN, 10 [JOHN, A FRAMEWORK FOR THE MORAL ANALYSIS OF MARKETS, 10/1, http://www.teacheconomicfreedom.org/files/larrivee-paper-1.pdf] The Second Focal Point: Moral, Social, and Cultural Issues of Capitalism Logical errors abound in critical commentary on capitalism. Some critics observe a problem and conclude: “I see X in our society. We have a capitalist economy. Therefore capitalism causes X. ” They draw their conclusion by looking at a phenomenon as it appears only in one system. Others merely follow a host of popular theories according to which capitalism is particularly bad. 6 The solution to such flawed reasoning is to be comprehensive, to look at the good and bad, in market and non-market systems. Thus the following section considers a number of issues—greed, selfishness and human relationships, honesty and truth, alienation and work satisfaction, moral decay, and religious participation—that have often been associated with capitalism, but have also been problematic in other systems and usually in more extreme form. I conclude with some evidence for the view that markets foster (at least some) virtues rather than undermining them. My purpose is not to smear The critical point is that certain people thought various social ills resulted from capitalism, and on this basis they took action to establish alternative economic systems to solve the problems they had identified. That they failed to solve the problems, and in fact exacerbated them while also creating new problems, implies that capitalism itself wasn’t the cause of the problems in the first place communism or to make the simplistic argument that “capitalism isn’t so bad because other systems have problems too.” , at least not to the degree theorized. Impact Turns TURN: Cap solves war. HARRISON Harrison ’11 (Mark, Department of Economics, University of Warwick, Centre for Russian and East European Studies, University of Birmingham, Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace, Stanford University, “Capitalism at War”, Oct 19 http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/staff/academic/harrison/papers/capitalism.pdf) Capitalism’s Wars America is the world’s preeminent capitalist power. According to a poll of more than 21,000 citizens of 21 countries in the second half of 2008, people tend on average to evaluate U.S. foreign policy as inferior to that of their own many believe that wars are caused by America According to evidence, however, these beliefs are mistaken country in the moral dimension. 4 While this survey does not disaggregate respondents by educational status, apparently knowledgeable people also seem to , in the modern world, most ; this impression is based on my experience of presenting work on the frequency of wars to academic seminars in several European countries. the . We are all aware of America’s wars, but they make only a small contribution to the total. Counting all bilateral conflicts involving at least the show of force from 1870 to 2001, it turns out that the countries that originated them come from all parts of the global income distribution (Harrison and Wolf 2011). Countries that are rich er, measured by GDP per head, such as America do not tend to start more conflicts , although there is a tendency for countries with larger GDPs to do so. Ranking countries by the numbers of conflicts they initiated, the United States, with the largest economy, comes only in second place; third place belongs to China. In first place is Russia (the USSR between 1917 and 1991). What do capitalist institutions contribute to the empirical patterns in the data? Erik Gartzke (2007) has re-examined the hypothesis of the “democratic peace” based on the possibility that, since capitalism and democracy are highly correlated across countries and time, both democracy and peace might be products of institutions the same underlying cause, the spread of capitalist . It is a problem that our historical datasets have measured the spread of capitalist property rights and economic freedoms over shorter time spans or on fewer dimensions than political variables. For the period from Countries that share this attribute do not fight each other, so there is capitalist peace 1950 to 1992, Gartzke uses a measure of external financial and trade liberalization as most likely to signal robust markets and a laissez faire policy. of capitalism above a certain level, he finds, as well as democratic peace. Second, economic liberalization (of the less liberalized of the pair of countries) is a more powerful predictor of bilateral peace than democratization, controlling for the level of economic development and measures of political affinity. TURN: Cap self-corrects exploitation. History proves. AMES: (Freedom Manifesto: Why Free Markets Are Moral And Big Government Isn’t. Steve Forbes, Publishing Executive. Elizabeth Ames, Former Member of The Texas House Of Representatives. 2012 p. 86-88) In other words, the fact that people freely choose to enter into open market[s] exchange works to encourage cooperation and moral behavior. It’s true that sometimes one side may violate the terms of a voluntary transaction—for example, you buy a car tat’s a lemon. That’s why a free market requires a fair and impartial legal system—to enforce the terms of contracts and mediate disputes. The competition and openness of free market societies also help to curtail too much power and “greed”. Free markets allow newcomers to rise up and challenge major players. The flow of information in an open market society through institutions like a free press provides additional checks and balances. The examples of truly free markets self-regulat[ion] power ing of self-interest is demonstrated by historic . Some have functioned for years without interference from government. What happened? People did just fine. William Anderson, economics professor at Frostburg State University and a scholar at the Mises Institute, recounts, “For about a century after the founding of the United States, business activity faced little or no government regulation, especially compared with the situation in modern times.” America in the nineteenth century is much of today’s commercial law comes from merchant law—which arose spontaneously from merchants who needed common rules to conduct business not the only example of a self-regulating market. In their book, Money, Markets & Sovereignty, Benn Steil and Manuel Hinds write that was not developed by lawmakers but codified lex mercatoria—“ in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. The laws of lex mercatoria evolved of the road the customs and practices of beyond their borders. “Even outside the realm of common law systems, commercial practice has throughout history driven the codification of systems of law, and not vice versa.” Lex mercatoria included principles such as requiring that both parties act according to “good faith” and a general standard of “fair dealings,” in addition to fundamental These were enforced by merchant courts along trade routes spontaneous regulation takes place in free markets. the Internet is largely unregulated Yet markets have sprung up to aid consumers and businesses attempting to establish trust property rights. rules a system of called Pie Powder courts at merchant fairs that were separate from local legal systems. Bruce L. Benson, economics professr at Florida State University, not that lex mercatoria is but one illustration of the that He explains: “Merchant [law] evolves whenever commerce in medieval Europe were replayed in colonial America, and they are being replayed in Eastern Europe, Eastern Asia, Latin America, and cyberspace. Like the markets of medieval times, market. what Benson calls “ today still a for trust” in first-time transactions. He give the example of VeriSign, which provides a “trustmark” that Internet businesses can display, assuring customers that their personal data is secure. But that’s far from the only example. TURN: Cap solves warming. WHITMAN Whitman ’08 (Janet, February 19, pg. http://www.financialpost.com/story.html?id=317551) Global warming may get a saviour more effective than Al Gore capitalism. the huge moneymaking opportunity in going green will be the big driver that leads to the reining in of the greenhouse gasses soon and his doomsday Power-Point presentations: The former U.S. vice-president, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize last year for his work on climate change, is credited with bringing widespread attention to the issue. But release of , experts say. Money already is pouring into environmental initiatives and technologies in the United States. Experts expect investment in the area to explode over the next few years if, as anticipated, the government here imposes restrictions on the release of gases believed to be behind climate change. "Capitalism will drive this," said Vinod Khosla, founding chief executive of Sun getting consumers to curb their energy use has never worked -- unless they've had a financial incentive. "If we make it economic, it will happen," Microsystems and a longtime venture capitalist. Mr. Khosla, speaking on a panel at a recent investment summit on climate change at United Nations headquarters here, said he said. The expected government-mandated cap on carbon emissions already is fueling innovation. Venture capitalists, for instance, are investing in new technologies that would make cement -- a major producer of carbon emissions -- actually absorb carbon instead. Cement makers could practically give the product away and reap the financial reward from government carbon credits. Cap is key to space exploration and development Blundell ‘4 [John, director general of the Institute of Economic Affairs, “Mission to Mars must go private to succeed”, Feb 2, http://news.scotsman.com/marsexploration/Mission-to-Mars-mustgo.2499794.jp] Bush is not finding the billions himself. Rather the tab will be picked up by US taxpayers in perhaps 20 years’ time. What arrests me is the unchallenged assumption that space exploration must be a nationalised industry. The Soviet effort may be stalled but the Chinese seem committed to joining the race. The European Space Agency is a strange combination of nationalised bodies. NASA is a pure old-fashioned nationalised entity. I argue we should relinquish the expectationthat space has to be limited to vast quangos. The mindset we all share is an echo of the rivalry between the evaporated USSR and the still dynamic US. The first bleeps of the Sputnik galvanised the US into accelerating its space What we need is capitalists in space. Capitalism needs property rights, enforcement of contracts and the rule of law. The ideological tussle does not cease once we are beyond the ionosphere. With the exception of Arthur C Clarke, none of us imagined the entertainment potential from satellites. effort. Geostationary lumps of electronic gadgetry beam us our BSkyB television pictures. I remain in awe that Rupert Murdoch can place a device in the skies above Brazil that sends a signal to every home in each hemisphere. Who could have foreseen that mobile phones could keep us chattering without any wiring, or that global position techniques could plot where we all are to within a metre? These are business applications. Business is already in space. Markets detect and apply opportunities that are not envisaged by even the most accomplished technicians. I’m not saying Murdoch has special competences. I imagine he is as baffled by digital miracles as I am. The point is that companies define and refine what public bodies cannot achieve. Lift the veil of course and all those satellite firms are an intricate web of experts supplying ideas and services. We have an infant space market. What use will the Moon be? Is there value on Mars other than the TV rights? The answer is nobody can know. We can only make some guesses. The Spanish ships that set off for the US thought they would get to India. The Portuguese knew they’d reach China. The English followed them westwards seeking gold. In fact, they got tobacco. Events always confound expectations. The arguments for putting men on Mars are expressly vague from President Bush. Perhaps he was really bidding for votes. From my reading the best results may be medical. Zero, or low, gravity techniques may allow therapies of which we are ignorant. It seems facetious to suggest tourism may be a big part of space opportunity but as both the North and South poles are over-populated and there is a queue at the top of Mount Everest, a trip to the Sea of Tranquility may prove a magnet for the wealthy. Instead of NASA’s grotesque bureaucracy it may be Thomas Cook will be a greater force for exploration. NASA could be a procurement body. It need not design and run all space ventures. It could sub-contract far more extensively. Without specialised engineering expertise it is not easy to criticise projects such as the shuttle. It seems to be excessively costly and far too There are private space entrepreneurs already. They are tiddlers up against the mighty NASA. Yet Dan Goldin, the NASA leader, says he favours the privatisation of space: "We can’t afford to do solar system exploration until we turn these activities over to the cutting edge private sector... "Some may say that commercialising portions of NASA’s functions is heresy. Others may think we are taking a path that will ruin the wonders of space. I believe that when NASA can creatively partner, all of humankind will reap the benefits of access to open space". Is it possible the Moon has a more noble future than merely a branch office of NASA? Is it tolerable that Mars could be a subsidiary of the USA? Could it be nominally a further state of the union? These are not silly questions. In time space will be defined by lawyers and accountants as property rights will need to be deliberated. One fragile. possibility may be that both environments are so hostile that Mars and the Moon will never be more than token pockets for humanity. On the evidence so far it is the orbiting satellites that have made us see the Earth through new eyes. We can survey and explore the planet better from 200 miles up than stomping on the surface. The emerging commercial body of space law is derived from telecommunications law. It is perplexing and contrary to our immediate senses. How can you own or exchange something as intangible as digital messages bouncing off satellites? Yet we all pay our mobile phone bills. Many of the business results of space exploration are unintended consequences of NASA’s early adventures. Computer development would probably have been slower but for the need for instrumentation for Apollo. Are there prospects for Scottish firms in space? The prizes will not go to only the mega corporations. Perhaps Dobbies, the Edinburgh garden centre group, can create new roses by placing pots beyond gravity. Edinburgh University laboratories, or rather their commercial spin offs, could patent new medicines. Is it possible the genetic magicians at the Bush could hitch a ride into space and extend their discoveries? NASA is a monopolist. All monopolies are bad for business. They only stunt opportunities. They blunt alternatives. By opening space to entrepreneurship we will be starting on what FA Hayek memorably describes as "a discovery procedure". Science is an open system. So is capitalism. (b) Space k2 solve a laundry list of impacts Pelton ‘3 [Joseph N. Pelton is director of the Space & Advanced Communications Research Institute at George Washington University and executive director of the Arthur C. Clarke Foundation “COMMENTARY: Why Space? The Top 10 Reasons”, Sept 12, http://www.space.com/news/commentary_top10_030912.html] Actually the lack of a space program could get us all killed. I dont mean you or me or my wife or children. I mean that Homo sapiens as a species are actually endangered. Surprising to some, a well conceived space program may well be our only hope for long-term survival. The right or wrong decisions about space research and exploration may be key to the futures of our grandchildren or great-grandchildren or those that follow. Arthur C. Clarke, the author and screenplay writer for 2001: A Space Odyssey, put the issue rather starkly some years back when he said: The dinosaurs are not around today because they did not have a space program. He was, of course, referring to the fact that we now know a quite largish meteor crashed into the earth, released poisonous Iridium chemicals into our atmosphere and created a killer cloud above the Earth that blocked out the sun for a prolonged period of time. This could have been foreseen and averted with a sufficiently advanced space program. But this is only one example of how space programs, such as NASAs Spaceguard program, help protect our fragile planet. Without a space program we would not know about the large ozone hole in our atmosphere, the hazards of solar radiation, the path of killer hurricanes or many other environmental dangers. But this is only a fraction of the ways that space programs are crucial to our future. Protection against catastrophic planetary accidents: It is easy to assume that an erratic meteor or comet will not bring destruction to the Earth because the probabilities are low. The truth is we are bombarded from space daily. The dangers are greatest not from a cataclysmic collision, but from not knowing enough about solar storms, cosmic radiation and the ozone layer. An enhanced Spaceguard Program is actually a prudent course that could save our species in time. 1. Alternative risks Transition wars Aligica 3 (Paul, 4/21, fellow at the Mercatus Center, Hudson Insitute, “The Great Transition and the Social Limits to Growth: Herman Kahn on Social Change and Global Economic Development”, April 21, http://www.hudson.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=publication_details&id=2827) Stopping things would mean if not to engage in an experiment to change the human nature, at least in an equally difficult experiment in altering powerful cultural forces: "We firmly believe that despite the arguments put forward by people who would like to 'stop the earth and get off,' it is simply impractical to do so. Propensity to change may not be inherent in human nature, but it is firmly embedded in most contemporary cultures. People have almost everywhere become curious, future oriented, and dissatisfied with their conditions. They want more material goods and covet higher status and greater control of nature. Despite much propaganda to the contrary, they believe in progress and future" (Kahn, 1976, 164). As regarding the critics of growth that stressed the issue of the gap between rich and poor countries and the issue of redistribution, Kahn noted that what most people everywhere want was visible, rapid improvement in their economic status and living standards, and not a closing of the gap (Kahn, 1976, 165). The people from poor countries have as a basic goal the transition from poor to middle class. The other implications of social change are secondary for them. Thus a crucial factor to be taken into account is that while the zero-growth advocates and their followers may be satisfied to stop at the present point, most others are not. Any serious attempt to frustrate these expectations or desires of that majority is likely to fail and/or create disastrous counter reactions. Kahn was convinced that "any concerted attempt to stop or even slow 'progress' appreciably (that is, to be satisfied with the moment) is catastrophe-prone". At the minimum, "it would probably require the creation of extraordinarily repressive governments or movements-and probably a repressive international system" (Kahn, 1976, 165; 1979, 140-153). The pressures of overpopulation, national security challenges and poverty as well as the revolution of rising expectations could be solved only in a continuing growth environment. Kahn rejected the idea that continuous growth would generate political repression and absolute poverty. On the contrary, it is the limits-to-growth position "which creates low morale, destroys assurance, undermines the legitimacy of governments everywhere, erodes personal and group commitment to constructive activities and encourages obstructiveness to reasonable policies and hopes". Hence this position "increases enormously the costs of creating the resources needed for expansion, makes more likely misleading debate and misformulation of the issues, and make less likely constructive and creative lives". Ultimately "it is precisely this position the one that increases the potential for the kinds of disasters which most at its advocates are trying to avoid" (Kahn, 1976, 210; 1984). Capitalism is self-correcting and sustainable – war and environmental destruction are not profitable and innovation solves their impacts – TAKES OUT THEIR IMPACT EVIDENCE Kaletsky ’11 (Anatole, editor-at-large of The Times of London, where he writes weekly columns on economics, politics, and international relationsand on the governing board of the New York-based Institute for New Economic Theory (INET), a nonprofit created after the 2007-2009 crisis to promote and finance academic research in economics, Capitalism 4.0: The Birth of a New Economy in the Aftermath of Crisis, p. 19-21) capitalism is a system built for survival. It has adapted successfully to shocks of every kind, to upheavals in technology and economics, to political revolutions and world wars. Capitalism has been able to do this because, unlike communism or socialism or feudalism, it has an inner dynamic akin to a living thing. It can adapt and refine itself in response to the changing environment. And it will evolve into a new species of the same Democratic capitalist genus if that is what it takes to survive. In the panic of 2008—09, many politicians, businesses, and pundits forgot about the astonishing adaptability of the capitalist system. Predictions of global collapse were based on static views of the world that The self-correcting mechanisms that market economies and democratic societies have evolved extrapolated a few months of admittedly terrifying financial chaos into the indefinite future. over several centuries were either forgotten or assumed defunct. The language of biology has been applied to politics and economics, but rarely to the way they interact. Democratic capitalism’s equivalent of the biological survival instinct is a built-in capacity for solving social problems and meeting material needs. This capacity stems from the principle of competition, which drives both democratic politics and capitalist markets. Because market forces generally reward the creation of wealth rather than its destruction, they direct the independent efforts and ambitions of millions of individuals toward satisfying material demands, even if these demands sometimes create unwelcome by-products. Because voters generally reward politicians for making their lives better and safer, rather than worse and more dangerous, democratic competition directs political institutions toward solving rather than aggravating society’s problems, even if these solutions sometimes create new problems of their own. Political competition is slower and less decisive than market competition, so its self-stabilizing qualities play out over decades or even generations, not months or years. But regardless of the difference in timescale, capitalism and democracy have one crucial feature in common: Both are mechanisms that encourage individuals to channel their creativity, efforts, and competitive spirit into finding solutions for material and social problems. And in the long run, these mechanisms work very well. If we consider democratic capitalism as a successful problem-solving machine, the implications of this view are very relevant to the 2007-09 economic crisis, but diametrically opposed to the conventional wisdom that prevailed in its aftermath. Governments all over the world were ridiculed for trying to resolve a crisis caused by too much borrowing by borrowing even more. Alan Greenspan was accused of trying to delay an inevitable "day of reckoning” by creating ever-bigger financial bubbles. Regulators were attacked for letting half-dead, “zombie” banks stagger on instead of putting them to death. But these charges missed the point of what the democratic capitalist system is designed to achieve. In a capitalist democracy whose raison d’etre is to devise new solutions to long-standing social and material demands, a problem postponed is effectively a problem solved. To be more exact, a problem whose solution can be deferred long enough is a problem that is likely to be solved in ways that are hardly imaginable today. Once the self-healing nature of the capitalist system is recognized, the charge of “passing on our problems to our grand-children”—whether made about budget deficits by conservatives or about global warming by liberals—becomes morally unconvincing. Our grand-children will almost certainly be much richer than we are and will have more powerful technologies at their disposal. It is far from obvious, therefore, why we should make economic sacrifices on their behalf. Sounder morality, as well as economics, than the Victorians ever imagined is in the wistful refrain of the proverbially optimistic Mr. Micawber: "Something will turn up."