Final Revision: June 24, 2003

HB/cb

..

CARICOM SINGLE MARKET AND ECONOMY

ASSESSMENT OF THE REGION'S SUPPORT NEEDS

Prepared for the Caribbean Community Secretariat

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

ACP

ACS

ADR

ASYCUDA

BEST

BHTA

BIDC

CA

CABA

CAHFSA

CAMID

CAP

CARDI

CARICAD

CARICOM

CARIFORUM

CARIFTA

CARIRI

CARISEC

CASE

CBO

CCJ

CCMS

ccs

CDB

CDERA

CDM

CEDC

CEHI

CET

CFRAM

CFTC

CHA

CIDA

CLA

CLIC

COFAP

COHSOD

CORE

COSTATT

COTED

CP

African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States

Association of Caribbean States

Alternative Dispute Resolution

Automated System for Customs Data

Barbados Environmental and Sustainable Tourism

Barbados Hotel and Tourism Association

Barbados Investment and Development Co-operation

Codex Alimentarius

Consumer and Business Affairs

Caribbean Agricultural Health and Food Safety Association

Caribbean AgriBusiness Marketing Intelligence and Development Network

Common Agricultural Policy

Caribbean Agricultural Research and Development Institute

Caribbean Center for Development Administration

9aribbean Community

Caribbean Forum of African, Caribbean and Pacific States

Caribbean Free Trade Agreement

Caribbean Research Institute

CARICOM Secretariat

College of Agriculture Science and Education

Community Based Organization

Caribbean Court of Justice

Caribbean Center for Monetary Studies

Caribbean Community Secretariat

Caribbean Development Bank

Caribbean Disaster Emergency Response Agency

Comprehensive Disaster Management

Caribbean Export Development Agency

Caribbean Environmental Health Institute

Common External Tariff

CARICOM Fisheries Resource Assessment Management

Commonwealth Fund for Technical Co-operation

Caribbean Hotel Association

Canadian International Development Agency

Committee of Lead Agencies

Caribbean Law Institute Center

Council for Finance and Planning

Council for Human and Social Development

Caribbean Oceanographic Resources Exploration

College of Science, Technology and Applied Arts of Trinidad and Tobago

Council for Trade and Economic Development

Competition Policy

CPC

CPU

CRNM

CROSQ

cs

CSME

CTHRC

CTO

CTO

CUBiC

CXC

DFID

DFIDC

DGIV

Dlffi,

DSU

EC

ECJ

ECLAC

EDF

EEA

EEC

EITA

EFZ

EP

EPA

ERDF

ESM

EU

EXED

FAA

FAO

FPG

ITAA

ITC

ITZ

FZ

GAP

GATS

GAIT

GC

GDP

GIS

GP

GPA

GTZ

Chief Parliamentary Counsel

Community Procurement Vocabulary

CARICOM Regional Negotiating Machinery

CARICOM Regional Organization for Standards and Quality

CROSQ Signatories

CARICOM Single Market Economy

Caribbean Tourism Human Resource Council

Caribbean Trade Organization

Caribbean Tourism Organization

Caribbean Uniform Building Code

Caribbean Examination Council, Secondary Education Certificate Examination

Department for International Development

Division for International Development in the Caribbean

Directorates-General of the European Union -- Competition

Draft Model Law

Disputes Settlement Understanding

Eastern Caribbean

European Court of Justice

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean

European Development Fund

European Environmental Agency

Eastern European Countries

European Free Trade Association

Export Free Zone

European Parliament

Environmental Protection Agency

European Regional Development Fund

Emergency Safeguard Mechanism

European Union

Excelsior Community College

Federal Aviation Administration

Food and Agriculture Organization

Future Policy Group

Free Trade Area of the Americas

Federal Trade Commission

Free Trade Zone

Free Zone

Good Agriculture Practices

General Agreement on Trade in Services

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

General Counsel

Gross Domestic Product

Geographic Information System

Government Procurement

General Procurement Agreement

Deutsche Gesellschaft fiir Technische Zusammenarbeit

HCL

HEART

HEART/NTA

HRD

HS

IADB

IASA

ICAO

ICT

IDA

IDB

HCA

ILO

IMO

INFOSERV

IP

1PM

IPR

JAMPRO

LAC

LDC

LID

LIDD

MARPOL

MCR

MDC

MERCOSUR

METROPOLIS

MNC

MS

MTS

NABs

NGCP

NGGP

NGO

NRCA

NSB

NTA

OECD

OECS

PAM

PCT

PEP

PROCICARIBE

R&D

Harmonized Customs Legislation

Human Employment and Resource Training Trust

The HEART National Trust Agency

Human Resource Development

Harmonized Standards

Inter-American Development Bank

International Aviation Safety Organization

International Civil Aviation Organization

Information and Communication Technology

Interchange of Data between Administrations

Inter-American Development Bank

Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture

International Labor Organization

International Maritime Organization

INFOSERV (Information and Services) Institute of Technology

Intellectual Property

Integrated Pest Management

Intellectual Property Right

Jamaica Promotions Corporation

Latin America and the Caribbean

Less Developed Country

Legal and Institutional Division

Legal and Institutional Development Division

The International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships

Merger Control Regulation

More Developed Country

Mercado Comun del Sur

Metrology in Support to Precautionary Sciences and Sustainable Development

Policies

Multi-National Corporation

Member State

Multilateral Trading System

National Accreditation Bodies

Negotiating Group on Competition Policy

Negotiating Group on Government

Non-governmental Organization

Natural Resources Conservation Authority

National Standard Bureau

National Training Agency

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

Organization of Eastern Caribbean States

Probable Associate Member

Patent Co-operation Treaty

Public Education Program

The Caribbean Agricultural Science and Technology Network System

Research and Development

RADA

RASOS

RBTI

REPAHA

RJLSC

RNM

ROSE

RRPP

RTP

SACU

SBDC

SE

SIDSPOA

SME

SRC

TIDCO

TNC

TOR

TRIPS

TIMA

TVET

UG

UNCTAD

UNDP

UNECLAC

UNESCO

UPOV

USAID

USDA

UTECH

UWI

UWICED

VTMIS

wco

WGTCP

WIPO

WPGR

WTO

Regional Agricultural Development Authority

Regional A via ti on Safety Oversight System

Royal Bank of Trinidad and Tobago

Regional Program for Animal Health Assistants

Regional Judicial and Legal Services Commission

Regional Negotiating Machinery

Reform of Secondary Education

Regional Resource Pooling Program

Regional Transformation Program

South African Customs Union

Small Business Development Company

Societas Europaea

Small Island Developing States Plan of Action

Small- and Medium-sized Enterprise

Scientific Research Council ·

Tourism and Industrial Development Company

Trade Negotiations Conupittee

Term of Reference

Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights

Trinidad & Tobago Manufacturers Association

Technical and Vocational Education and Training

University of Guyana

UN Conference on Trade and Development

United Nations Development Program

United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

Protection of New Plant Species

US Agency for International Development

United States Department of Agriculture

University of Technology

University of the West Indies

UWI Center for Environment and Development

Vessel Traffic Management and Information Systems

World Customs Organization

Working Group on Trade and Competition Policy

World Intellectual Property Organization

Working Party on GATS Rules

World Trade Organization

CONTENTS

FOREWORD .......................................................................................................... i

INTRODUCTION ...... ...... ..... ......................................... .. ............................... ... ... ii

I.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............. ....... ........ ....................................................... 1

II.

INSTITUTIONAL AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK. .......... .... ........ .-..................... 22

(A) Background: The Treaty of Chaguaramas ........ ......................................... 22

(B)

Provisions for the Harmonization of Laws~ ..... ........................................... 24

(C)

Operationalizing the Caribbean Court of Justice ........................................ 41

(D) Disputes Settlement ........................................................., .......................... 45

(E)

The CARICOM Regional Organization for Standards and Quality ........... 53

(F)

Competition Policy ..................................................................................... 60

(G) Intellectual Property .................................................................................... 76

(H) Government Procurement ........................................................................... 94

(I)

CSME Public Education Program ................ ......... ......... ...... .. ..: ............... 109

Tables 11-1 to II-8 ...................................................................................... ......... 113

III.

MARKET ACCESS .................................................................................. ......... 136

(A) Trade in Goods .......................................................................................... 138

(B)

Rights of Establishment, Provision of Services and Movement

of Capital. ............................ ............................................................. ... ...... 144

(C)

Setting of Priorities ................ ......................................... .......................... 156

Table III-l ................ ........... ..... ....... ............ .. ................ ................... ............ ...... 158

IV.

CARICOM SECTORAL DEVELOPMENT POLICIES .................................. 159

(A) Agricultural Policy ................... .. ........ ..... ..... ............................................. 164

(B)

Industrial Policy ........................................................................................ 1 77

(C)

Services Sector Policy ............................................................................... 195

(D) Transport Policy .................................................................... .... ... ............. 206

(E)

Environmental Protection Policy .............................................................. 235

(F)

Tourism Policy .......................................................................................... 245

(G) Research and Development.. ..................................................................... 252

(H) Information Communication Technology Policy ..................................... 273

(I)

V.

Human Resource Development Policy ..................................................... 287

THE MACROECONOMIC FRAMEWORK .................................................... 304

(A)

Macroeconomic Policy Coordination ...... .,.............................................. 304

(B)

Fiscal Policy Harmonization ................................................................... 305

(C)

Investment Policy Harmonization ........................................................... 308

(D)

Financial Policy Harmonization .......................................................... .... 309

(E)

Regional Development Fund for Disadvantaged Countries,

Regions and Sectors ......................................................... ....................... 311

(F)

Monetary Union/Single Currency ........................................................... 313

Table V-1 ....... ........ ............................................................................................ 316

VI.

PRIORITIZATION ACTION PLAN AND THE ROLE OF DONORS ........... 318

(A)

Prioritization ........................ ................ ........ ............. .. .................... ......... 318

(B)

The Role of Donors ................................................................ ................. 321

Tables VI-1 to VI-2 ............................................................................................ 324

ANNEX I- List of Consultants ......................................................................... 336

ANNEX II -Terms of Reference ..................................................................... 337

FOREWORD

This project commenced on 5 February, 2002 and the first-draft chapters of the report were

discussed at a meeting with CCS staff on 6 May, 2002. Subsequent drafts of the report benefited

from detailed comments and suggestions made by staff members of the Caribbean Community

Secretariat (CCS). Views expressed at a meeting of public, private and civil sector interests

convened in Barbados, 23-24 November, 2002 were also taken into account. Final comments

and other material were received from the CCS on 26 March and 7 April, 2003 and were used as

appropriate in preparing this final version of the report.

The consulting team wishes to thank the Caribbean Development Bank (CDB), and the United

Kingdom Department for International Development (Caribbean) (UK - DFID), for the financial

and organizational support and other facilities placed at their disposal; the government agencies

and private sector representatives consulted for their time in discussing the issues; and the staff

of the CCS for patiently assisting them with information and comments, and for the generous

facilities and courtesies extended to the team.

Havelock R. Brewster

Team Coordinator

June 24, 2003

Tel: (202) 623-1039

Fax: (202) 623-3611

Email: hbrewster@aol.com

INTRODUCTION

The CARI COM Single Market and Economy (CSME) is the flagship of the regional integration

movement, aimed at creating a single economic space which will support competitive production

'

.

within CARICOM for

both intra-regional

and

extra-re~onal

markets.

It is considered critical to

. ..

.

.

.

.. .

. ..

a,s, «..r,:;:cza

.e _ . _

..

...d

the future growth and development of the Region, and intended to ensure that CARJCOM

effectively surmounts the challenges and difficulties that confront Member States and keep pace

with the changing global economic climate.

T~e problems and challenges faced by the Region are often obscured by relatively high social

and economic indicators.

Based on the Human Development Report 2002, the Human

Development Indicators (HDI) for CARICOM States were reasonably high, except in the case of

Haiti. Four countries. (Barbados, The Bahamas, St Kitts and Nevis, and Trinidad and Tobago)

ranked in the first 50. Life expectancy in the Region is over 70 years, except in Guyana and

Haiti. Adult literacy is over 80 per cent, except in the case of Haiti, and GDP per capita levels

-

place the Region in the medium-developed category.

- - --------

Despite substantial social and economic progress, CARICOM States continue to be confronted

!' ,

by a number of imposing challenges, including the high prevalence and rising incidence of ;

HIV/AIDS; increasing poverty, varying among countries in severity and rural/urban distribution;

high rates of unemployed youth; drug abuse, violence and crime, linked to the narcotic drug

trade, and their growing threat to security; the loss of trade preferences for the traditional

products of bananas, rice, sugar and rum, resulting in loss of market security; the negative eff~ct

on offshore financial services, an area in which Member States enjoyed a comparative

advantage, by OECD actions to counter money-laundering; and the impact of changes in

information and communication technology, in giving rise to new economic activities based on

knowledge and information at the expense of traditional natural resources-based industries.

These problems are exacerbated by the small size and opell!ess of CARICOM economies which

expose them to external economic shocks and changes in the terms of trade beyond their control;

·· - · ·· - -··-·-- --------- ----····-·-··-· - .. ···------···--------------------· --- ------ . - .. .

limit their human resource capacity and encourage high rates of migration. In addition, most of

.

-----

--- -

.. . --- - ....

------------

11

----- - - ------ ---- - ------

.

-

'\ these countries are vulnerable to natural disasters, especially hurricanes, which frequently create

disproportionate social and economic distress.

The main components of the CSME were inscribed during the 1990s in nine Protocols amending

the Treaty of Chaguaramas Establishing the Caribbean Community (1973).

Each of these

Protocols addressed a specific area of concern, namely; Decision-Making Institutions; Rights of

Establishment, Provision of Services and Movement of Capital; Industrial Policy; Trade Policy;

Agricultural Policy; Transport Policy; Disadvantaged Countries, Regions and Sectors;

Competition Policy and Consumer Protection; Dispute Settlement.

The content of these

Protocols has been incorporated (since July 2001) into the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas .

Establishing the Caribbean Community including the CARICOM Single Market and Economy, a

Protocol for the Provisional Application of which has been s!gned by most Member States.

The Consultants were requested, building on the existing CARJCOM consultancy and updated

work plan on the CARJCOM Single Market and Economy (CSME), and taking into account the

changing external environment to:

a)

Indicate priority areas, in the short and medium-term, for the implementation of the

CSME and bringing it fully into operation; identifying the progress on

_implementation at the national and regional levels, what has been accomplished to

date, what is currently under way, and what is yet to be achieved.

b)

Review the institutional arrangements, national and regional, for each priority area

and the capacity and mechanisms available to implement and meaningfully

participate in the CSME.

c)

Make recommendations for taking the process of implementing the CSME forward in

the short, medium and long-term, cognizant, among other things, of the need to

address regional and national issues in the context of the external environment, and

other relevant integration experiences such as the European Union.

For purposes of organizing the project, we grouped the major areas into four broad categories,

namely:

nThe Institutional and Legal Framework

ll1

(The Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas; the Caribbean Court of Justice; Harmonization of

Legislation;

Standards;

Competition Policy;

Intellectual

Property;

Government

Procurement, and the CSME Public Education Program)

['{ Intra-Regional Market Access

(Trade in Goods; Rights of Establishment; Provision of Services and Movement of

Capital)

(I Community Sectoral Development Policies

(Agricultural; Services;· Industrial; Transportation; Environmental Protection; Research

and Development; Tourism, Information Communication Technology, Human Resource

Development)

{( The Macroeconomic Framework

(Macroeconomic Policy Coordination; Fiscal Policy Harmonization; Investment Policy

Harmonization; Financial Policy Harmonization; Regional Development Fund; Monetary

Union/Single Currency).

The project was designed as short-term technical assistance to the CCS, extending over a period

of a few weeks.

However, it turned out to be far more complex and wider in scope than

anticipated, and if taken literally, well beyond the time and resources available to the project.

J~ Weaknesses

limpediments.

in communication between the CCS and the Member Governments were also

r

It was realized following the commencement of the project, that if the exercise was to be useful

in the assessment of priorities, potential outcomes, and levels of support needed, understanding

---------·------------- -- - - - - - - - --

---··- - - · ·

the substantive-conte~t. as distinct from pursuing the formal agenda, would be essential and

would call for some explanation, even if this could not be undertaken in-depth.

·<

. - ---·-------··-------- - - · - - - - - ---·

Ideally, this exercise would have entailed detailed investigations of all aspects of the CSME in

each individual Member State, and a determination in quantitative and specific terms of the

IV

resources and specialized expertise needed by the Community institutions and the Member States

to bring the various outstanding instruments into operation.

Literally hundreds of pieces of legislation and related instruments, government directives and

enabling facilities across the region are involved. To give just one example, it was estimated that

in respect of the harmonization of legislation some 400 instruments would be affected. This task

i\

is not made any easier by the fact that to date there 1:;;;s not exist a comprehensive listing of the

I instruments that would need to be changed in each jurisdiction.

rnThis situation impeded to some extent the drawing up c;,f an agenda for the futur~, including

Vlquantitatively precise and credible estimates of the resources needed. In most instances then our

work had to be based on whatever material was available at or through the CCS Headquarters in

Georgetown, Guyana, and what could be learned through short missions undertaken by some of

the Consultants to Barbados, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, and to the Headquarters of the

Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) in St. Lucia.

As the project proceeded and we became aware of the existence and content of parallel exercises,

both within the CCS and by external Consultants, consequential adjustments to our approach

became necessary, and had to be made so as to ensure that our product would be complementary.

These parall~l exercises are referred to where they exist and are relevant, in the chapters that

follow. Their results would have to be considered in conjunction with the present report. They

include, among others, the CCS's periodic status reports on the implementation of the CSME, its

work programs, and a detailed report, including a Plan of Action (together with a quantitative

needs assessment), entitled "Implementing the CARICOM Single Market and Economy,"

prepared by the Consultant John Kissoon, sponsored by the Canadian International Development

Agency (CIDA). Certain other studies referred to in the text that are relevant to an assessment of

various aspects of the CSME, and of the resources needed to advance its implementation, are still

m progress.

~ The present exercise, therefore, complements the CCS's implementation status reports and work

{ programs, John Kissoon's report, and other relevant studies in progress by providing greater

\ substantive and policy evaluation of what remains to be dpn~--;i-~~ti~g -th~--;ork~;re rele;ant,

'

--·----·----·--·-·-···--- -·· -- -···--·--

V

at the interface with the external environment, in particular, the ongoing process of external

negotiations; drawing on the experience, where useful, of the European Union (EU), the most

directly relevant and advanced process of integration among States; indicating the type and level

of assistance needed; and attempting some prioritization, both within and across areas.

In regard to the matter of assistance, we considered it more credible to indicate the resources

needed by orders of magnitude, rather than by specific quantities, given the inadequacy of

information at this stage, and the fact that in any event more precise quantities would have to be

determined at the point of preparation of project proposals. The ordinal ranking of levels of

assistance needed ranges from low (less than 12 ·work-months) to medium (12 to 36 workmonths) and high (more than 36 work-months).

The subject matter of the various areas 1s very different, and so is the relevance of and

information available on the various aspects of the evaluation the Consultants were asked to

undertake. This made it difficult to follow a strictly uniform approach and presentation. Each

Consultant, therefore, while responding to the basic questions asked, followed a scheme that

seemed appropriate to the issues being addressed.

We took the task literally, in the sense that decisions, instruments and policies were addressed as

adopted by .the Community authorities, and we did not consider it within our mandate to question

them in any way.

It was thus also not the intention to prepare comprehensive detailed

prescriptions for policies and interventions in the various economic sectors. Questions, however,~

do arise about the approaches or options chosen in respect of many CSME policies 3:nd

instruments, their content, assigned priority, feasibility, and prospective benefits.

·

An impressive range of decisions has been made by the Community Council on the CSME, and

some activity has been proceeding across most of the areas, especially preparatory work at the

national and regional levels, such as diagnostic and informational studies, and the drafting of

legal instruments and donor assistance project proposals. However, the stage of implementation

has not yet been attained for most decisions and instruments, with the exception of the free

movement of goods, a .policy that pr-e-dated the CSME mandate.

Vl

I

Nevertheless, the need to implement the CSME has been persistently pressed by governments

and the private sector, especially in view of the expected conclusion of the FTAA and WTO

Doha negotiations by 2005, and the ACP-EU Negotiations by 2007. The mutual recriminations

that have characterized relations between the Community and the private sector over the slow

pace of implementation of the CSME need to be replaced by more constructive cooperation.

The expectation has been that the CSME would be the precursor to integration into the world

economy, and that its realization would enhance the region's export competitiveness and put the

Community in a stronger negotiating position. The Regional Negotiating Machinery (RNM) has

repeatedly stressed the importance of achieving this, and, indeed, as the relevant Chapters of this

report indicate, the fact that in many respects, effective participation in those international

agreements is premised on CARICOM putting in place those negotiating positions, policies and

instruments that directly interface with those events. In t~is _connection, it should also be borne

in mind that CARICOM can be diluted if it fails to preserve its rights in the WTO under the

<

GATT Article 24; GATS Articles, and as an integration grouping of developing countries. These

,

'

r

-.::--

rights would be diluted only if Member States individually make concessions contrary to the.

\

'

Treaty obligations and without regard to their multilateral rights.

The substantive chapters are presented in the broad categories mentioned above. In respect of

each of the areas, apart from an assessment of the state of implementation, a separate

identification is included of the type and level of assistance needed, as well as a priority-ranking

of activities within each area, based on our assessment of their possible economic impacts over

the short, medium and long-term. In the final chapter, a cross-area prioritization analysis is

presented.

Vll

CHAPTER!

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

INSTITUTIONAL AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Sections (A) to (D) of Chapter II of the report set out the action taken to-date with respect to the

main provisions for the harmonization of laws under the revised Treaty of Chaguaramas. In this

respect, the need to quantify and analyze the amount of work that has yet to be done is

highlighted, particularly in relation to Chapter 3 of the Revised Treaty 1•

Some of the key issues and concerns that arise in relation to the development of new Draft

Model Laws are identified. Emphasis is given to the need for jurisprudential cohesiveness in the

drafting of laws; the urgent need for more lawyers in several fields; the need to reorganize and

redefine the future role of the Legal and Institutional Division (LIDD) once the amount of

internal and external legal and legal institutional work is quantified. The issue is raised of legal

. research policy capability within the LIDD that would complement and support the work of any

drafting facility.

The importance of developing the present legal environments in the different jurisdictions is

-·

underlined .so as to ensure that all model laws can be implemented and redress sought. The

inadequacy (indeed, in some cases, the complete absence) of legal professionals in some

is raised as a major concern. Such barriers to the implementation of the CSME

/_ jurisdictions

r

should be quantified.

Some of the key constraints in the development of Draft Model Laws are pointed to and

specifically comments are made on two key instruments i.e. the proposed Harmonized Customs

Legislation and Company Law. Proposals are made in relation to both, drawing on the amended

Kyoto Convention, for direction in the case of the former, and the EU and UK proposals in the

case of the latter.

1

A preliminary .computation of the work that has to be undertaken was provided by the -consultant to the Chief

Counsel and is not attached to this report.

1

The operational differences between the various company registries are highlighted and it is

suggested that there is a need to deal with the large number of inactive companies and registered

businesses. It is also proposed that modem company law enforcement procedures need to be

introduced - with new measures and penalties for non-compliance with the requirements of

Company Law for good governance .

.MT~~ ~ ~ a i s e d of the recognition and~~forcement of judgments of courts or tribun_als

~( which is so fundamental to the effective functioning of the economic community. It is suggested

··-

·-----·-···- ·-·--·-···-··- -··-

.

that there is a need for a protocol to cover this important area. Two model Conventions are

identified that operate in Europe (not just the EU) which could provide direction to CARI COM

when devising their protocol. The models, which are generally recognized to be effective but

complex, were forged bearing in mind the differences that_ exist between the common law and

civil law systems, hence their relevance to CARICOM.

The developments that have taken place in relation to the Caribbean Court of Justice are noted its funding, the preparation for its establishment and the role of the International Preparatory

Committee. The central role of the Regional Judicial and Legal Services Commission (RJLSC)

is noted and in its absence only a preliminary assessment of the technical assistance that may be

required by the CCJ could be made.

The recent establishment of CROSQ is noted.

Its role, proposed funding and anticipated

operating costs are set out. In the absence of a Secretariat and Strategic Plan only a preliminary

list of technical assistance could be proposed.

It is suggested that the implementation of the draft model laws throughout the Community, inter

alia, sets new parameters for the development of all future Public Education Programs (PEP). In

the future emphasis should be placed firmly on the benefits and opportunities that arise prima~ly

for the ordinary citizen but also for other legal persons, such as companies, within the CSM~.

Similarly, attention should focus on the practical benefits and responsibilities_that _!Y_g t ari_~~.fLQ!Il

the implementation of specific pieces of le~islation _under _:Treaty_obligatign.s. The need for

adequate financial support for the PEP is stressed. The creation of a good interactive Internet-

2

ba~€::d._website component is hi~hly_desirable. Ongoing evaluation, monitoring and review of the

program are strongly recommended.

Finally, the present provisions in relation to dispute settlement in the revised treaty, the WTO

Dispute Settlement Understanding and the FTAA proposals are set out. The similarities between

all the provisions are noted and some provisions where accommodation will have to be made by

CARICOM are highlighted. An in-depth study of this matter is needed. The importance of

---· ·

Alternative Disputes Settlement mechanisms referred to by CARI COM, WTO and FTAA are

also noted. The need is stressed for greater awareness and commitment of resources throughout

the Members States to the development of ADR and the training of professionals in this area.

Under the Revised Treaty, the currently under-resourced LIDD will have to provide legal

services in this area. The provisions of articles 196 and 205 in relation to the nomination of

conciliators or arbitrat.ors are noted and the need for immediate action in this respect.

COMPETITION POLICY

S_ection (E) of Chapter II on Competition Policy provides information under three themes: status

of implementation of Chapter 8 of the Treaty, consistency between this chapter and what is being

negotiated in the external environment, and a needs assessment. While some progress is being

made on implementation, only three Member States, Jamaica, Barbados, and St. Vincent, have

competition laws, and only Jamaica and Barbados have institutional arrangements to enforce the

law.

St. Vincent's law has not as yet been promulgated, and is not being enforced.

Most

Member States are in the process of drafting legislation, including sub-regional legislation for the

OECS Member States.

A major problem faced throughout the region is the severe lack of human and financial resources

to implement the regime.

Of urgency is the need to develop an inventory of the laws,

agreements, and administrative practices that are inconsistent with the provisions of Chapter 8.

Another issue to determine is what is the authority of the Commission to represent Member

States in relation to third parties, and, for instance, the proposed Competition Committee in the

FTAA? The section provides some insights on the legal basis of the authority vested in the EC

Commission to represent Member States.

3

This section explores the consistency between Chapter 8 and what is being negotiated in the

FTAA and ACP-EU negotiations, and discussions in the WTO with regard to competition policy.

One issue raised was that Member States need to decide whether they want Merger Control

Regulation (MCR) since it is in the draft bracketed text of the FTAA Chapter on Competition.

Further, while Chapter 8 is silent on MCR, the draft model law for CARICOM includes such

provisions. Another issue that needs to be explored further is the implication of applying the

core principles of transparency, non-discrimination and due process to third parties. Finally, the

section provides some lessons that could be gleaned from the experiences of other developing

countries in implementing and enforcing their competition regimes.

Needs identified centered around the scarcity of human and. financial resources to introduce and

implement the competition regime. Training is required in the drafting of legal documents, and

education at various levels is required. Professional training is required to prepare lawyers,

economists and trade experts to staff competition commissions at the national level, and the

Regional Commission. Education of stakeholders is necessary if the regime is to be accepted

and implementation be made less difficult. To achieve this, there is a need to organize seminars,

workshop, to have scholarships offered for university training, to send staff on internships, and to

develop courses at regional universities to provide sustainable training of human resource for the

region.

Assistance is needed to develop systems for transparency in terms of information

dissemination, and to develop library resources.

Substantial work is needed to develop the

inventory of laws, regulations and administrative practices that are contrary to chapter 8, for

submission to COTED by February 2004. There is also a need to determine where exemptions

may be needed, since most countries have exemptions from their competition laws, and in a trade

agreement context, this means that there could be an uneven playing field.

4

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

Section (F) of Chapter II provides, first, an overview of the TRIPS obligations, and then gives an

overview of the extent to which CARICOM countries have complied.

While Antigua and

Barbuda, Belize, Dominica, Saint Lucia, Barbados, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago have

complied, other countries have problems, largely due to scarcity of human resources, so that

some are not even responding to WTO requests for information.

These countries include

Grenada, Guyana, Suriname, Saint Kitts and Nevis, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. A

major issue being discussed at the TRIPS Council is the level of protection that can be given to

Geographical Indicators, and a concern is that one interpretation is that protection is given to a

region or province within a country, and not to a country.

In terms of plant vatieties, the possibility was posed that where countries had not previously

offered patent protection of plants, they may have until 2005 to comply with the requirement to

protect plant varieties by patents or a sui generis system.

A major problem is institutional

weakness, caused largely by lack of skilled personnel. OECS countries are considering setting

up a combined IP office, or even a combined IP and Competition Policy office.

The Cotonou Agreement reaffirms the TRIPS obligations, offers cooperation in preparation of

laws, establishment and reinforcement of domestic and regional offices and other agencies, and

training of personnel. It provides for further negotiations aimed at protecting trademarks and

geographical indicators. In the FTAA, the US wanted to take the negotiations to TRIPS plus, but

developing countries have resisted. There are extensive provisions in the FTAA draft chapter on

IP on the protection of indigenous knowledge, but at this point, the provisions are square

bracketed and are still to be negotiated.

The criteria to be met for obtaining protection of plant varieties is very complex, and a long time

period is needed before CARICOM countries could be prepared enough in order to be able to

benefit from this regime. It is proposed that pro-active measures be taken now to develop the

expertise in testing new plant varieties for the criteria for protection, and that the Department of

Agriculture of the University of the West .Indies could become a repository of skills in testing

5

tropical plants, not only for CARICOM countries, but for tropical countries generally, since there

is a vacuum in such skills at present.

With regard to progress in establishing a regional administrative body for IPR except copyrights,

modest progress has been made. A Working Group on IP was established in 2000, met twice,

and agreed to commission two studies from WIPO: the feasibility of establishing a regional

administrative body, and the feasibility of developing a regional anti-piracy system based on the

Banderole model. However, the terms of reference was not prepared and the group was not

reconvened between 2000 and 2002 because of lack of human and financial resources. Views on

the feasibility of a regional IP office that were solicited during interviews were reported.

There are few mechanisms established to ensure use of "prot~cted works" in the region, and the

real problem is not inventions, but support to take these to the commercial stage. Inventors have

little capital and are wary of joint ventures with large corporations. The region's business sector

has a history of investing very little in Research & Development (R&D). Similarly, there is little

know-how on how to use patented documents as a source of technological information to

advance R&D. A program of focused public education is needed across all IP issues, not just

copyright, which has been the emphasis so far in the region. There is ignorance both in the

public and private sectors on issues related to IP.

The Treaty calls for the preservation of indigenous culture, and it is assumed that this is meant in

the context of protecting the cultural products through establishing IPR. The paper suggests the

setting up of a committee to examine existing cultural practices and products that could meet the

criteria for. protection, and take action where possible. While TRIPS have no provisions on the

legal protection of folklore, other traditional knowledge and national heritage, particularly

indigenous populations of the Community, several Members have passed laws complying with

the obligations under the Convention on Biological Diversity.

Barbados and Trinidad and

Tobago protects the expressions of folklore. These laws could be examined and copied by other

Member States, where applicable. WIPO has done considerable work towards developing a

global system of protection of traditional knowledge.

6

Finally, the Treaty calls for measures to prevent abuse of IPR by right holders. It is noted that

Chapter 8 does not explicitly proscribe abuse of IP monopoly power, but Art. 66(f) of Chapter 4

explicitly calls for such measures. The draft model law on competition policy provides for

prohibition of anti-competitive conditions linked to sale or licensing of patented goods.

GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT

The Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas does not cover Government Procurement (GP), and there is

no regional system in place as yet. However, the Member States are currently negotiating a GP

chapter in the · FTAA.

Section (G) of Chapter II provides an in-depth view of the EU

Government Procurement regime, together with an understanding of the problems encountered

over the years of maturing of the system, and the measures .taken to overcome the problems. It

provides information ~m the objective of the EC system, who are affected by the rules, how the

system is structured and administered, and the problems encountered over the years in the

implementation of the regime. It then provides a detailed account of the key provisions of the

current regime.

Based on an analysis of this experience, recommendations are offered for

consideration when develqping a CSME regime. A brief discussion of the GP dimension of the

Cotonou Agreement is provided, as are the issues being discussed in the WTO and the FTAA.

MARKET .ACCESS

CARICOM Member States are confronting a complex challenge in respect of market access

issues, the subject of Chapter III in the report, aiming to complete the CSME by the year 2095,

they are engaged in multiple and simultaneous participati.on in trade negotiations at different

levels and of a differentiated nature. In such a context the major challenge is completing and

perfecting the regional integration scheme as an effective vehicle for development while

managing and adapting to a rapidly changing trading environment. This environment is signaled

by changes in the multilateral trading system (MTS) and a growing web of agreements that

increasingly infringe on sensitive development policy areas.

Since there is an overlapping

agenda in this process, the interface between regionalism and the international environment in

which it must operate emerge as a determining element for future development prospects,

impacting not only on the results and operation of the CSME, but possibly compromising its own

7

identity. The identification of those elements that will confer on CARICOM its individuality

within the changing trading environment, while effectively promoting sustainable development,

should be a primary focus of attention by Member States.

The required effort to effectively manage the interface between national development objectives,

regional initiatives and the overall trading environment demands synchronizing domestic

developmental requirements and objectives with external commitments in different layers of

integration.

This requires in tum developing a comprehensive development oriented trade

policy and a clear perspective of the implications of norms and disciplines being developed in

the different layers of integration, identifying in such a context additional spaces available for

action promoting development in the framework of the CSME. The identification of the required

"plus" elements demand a comprehensive analysis of the dif(erent rule-making developments in

the different layers - multilateral, hemispheric, regional and bilateral, identifying additional

spaces available for action at the regional level, assessing the political viability of adopting

further regional commitments, and evaluating what it would be possible to achieve and in what

timeframe. This assessment should constitute a central exercise by CARICOM Member States

guiding the setting of priorities in the context of the implementation of the CSME. Following

this line of thought, priority support should be provided for the definition and implementation of

a CARICOM Common External Economic and Trade Policy and for strengthening coordination

between the _CARICOM bodies entrusted with conducting external economic relations and those

responsible for the implementation of the CSME.

In the case of trade in goods, it could be concluded, after reviewing the current situation and the

ongoing programs, that the current arrangements and work program seem adequate to a large extent

to achieve the objective of the Customs Union.

Tariffs for intra-regional trade have been

dismantled, with very few exceptions remaining. The Common External Tariff (CET) is in the

process of final implementation, with only three Member States still having yet to implement Phase

IV. The highest priority should be given to institutional capacity-building at the national and

regional levels. Every day more demands are placed on trade management, both at the regional

level and in the international trading system, and these call for enhanced institutional capacities.

Technical Obstacles to Trade, Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures and Unfair Competition are

now dominant issues in trade, and their importance will only grow in the future. There are obvious

8

deficits in most CARICOM Member States in regard to their institutional capabilities in these areas.

Tue effective participation of Member States in the emerging trading system, and the smooth

functioning of the CSME, will depend to a large extent on developing further these capabilities in

trade-related institutions.

CARICOM has made important progress towards the implementation of the rights of

establishment, provision of services and movement of capital as provided by Chapter III of the

Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas. This is an area where there are significant possibilities of

advancing further at the CARICOM level than in other trade agreements in which the Member

States are participating, thereby conferring important differentiating elements to the CSME. The

Program for the removal of Restrictions should be closely monitored and support provided to

Member States for the domestic implementation of their commitments.

Further work is required mainly in two areas to guarantee an effective exercise of these rights by

CARICOM Member States nationals. On the one hand, rule-making developments are required

for the implementation of the Treaty rights and obligations, while on the other hand, the

domestic implementation of the obligations is in most cases still outstanding. Regarding rulemaking, completing the safeguard regime provided by Article 47 ·would provide predictability to

market access commitments made by Member States, while discipline in respect of subsidies and

the harmonization of incentives would guarantee a level playing field for services providers of

the Member States.

Special priority should be given to implementing a regime for the

liberalization of the temporary movement of natural persons supplying services (Mode 4),

including the free movement of skills where some progress is already evident; and a regime for

the acceptance of diplomas, certificates and qualifications.

Due to the importance of tourism for most of CARICOM Member States and their dependence

on maritime transport for trade, priority work should be undertaken for the adoption of the

Programs for Removal of Restrictions on maritime and air transport.

9

CARICOM SECTORAL DEVELOPMENT POLICIES

In terms of importance to CARICOM integration, it could be argued that Sectoral Programs

which are the subject of Chapter IV of the report are the most important because that is where the

productive resources of the Region are released to generate the output and wealth required to

produce growth and an improved standard of living for the people of the Region. It is selfdefeating to remove all restrictions to trade and to set up numerous institutions to enforce rules

and monitor activities, if the economic sectors that are to drive the process are themselves

neglected. It is therefore critical that the Organs of the Community should not under-estimate

the importance that_needs to be placed on Sect~ral Programs or assume that they can be treated

as residual and will somehow take care of themselves.

The Mission Statement of the Sectoral Programs Unit at the CCS does in fact reflect the

importance of Sectoral Programs. It states that the mission is to: Enhance competitiveness,

profitability and overall development of the productive sectors as a means to achieve sustained

cultural, social, economic and environmental objectives in pursuance of the improved quality of

life for all in the Caribbean Community.

However, the implementation of the CARICOM's sectoral policies is behind schedule and

relatively fe'Y regionally driven initiatives have been taken beyond the conceptual stage. Most of

the objectives or activities identified to support the goals of the sectoral policies outlined in the

Revised Treaty have either not progressed at all, or are at a stage where it is recognized that a

study is required to guide and inform the initial steps, or where a study is in progress or has been

completed. There are a few cases where some post-study implementation has taken place, such

as in the setting up of CROSQ or in defining programs for the removal of restrictions to the free

movement of services, the right of establishment and the free movement of capital. In general,

implementation has been hampered by a combination of a lack of financial resources,

technical/human resources, political will at the national level, and cooperation among Member

States.

The CCS is able to coordinate and act as a catalyst to the implementation of the objectives of the

sectoral policies, but in most cases significant financial and technical resources are required in

10

conjunction with ,coordinated actions at the national level.

Moreover, to be effective,

coordinated action has to come from all participating Member States at the same time.

This Chapter outlines some of the main initiatives that have taken place either at the regional

level or the national level across CARICOM. It was found that, in some areas of the sectoral

programs, implementation, where it has not taken place on a regional basis, might be assisted by

adopting or adapting best practices in one or two Member States that already have sound national

programs in place.

The seven main areas of Community Sectoral Policy examined .in this Chapter are agriculture,

services, industrial policy, transportation, environmental protection, research and development

and tourism. In none of these areas has there been significant progress in the implementation of

objectives.

In Maritime Transportation, Research and Development and Environmental

Protection, there is a general feeling that they receive low priority at the national level, and that

this explains the overall lack of development in these areas across the Region. The fact is that

serious action is required in all of the sectors if the Region is to achieve the objectives laid out in

the Revised Treaty. The priorities identified for each sector are summarized and listed below.

All of them basically require funding and/or technical assistance for their implementation.

Agricultural Sector

Elaboration of strategic plans for the remaining sixteen industries that have been

identified as having strong potential. These plans would identify strengths, weakness~s,

threats and opportunities in each industry and propose the regional mechanisms and

common policies needed for their development.

Development of the Caribbean AgriBusiness Marketing Intelligence and Development

Network (CAMID) as a strong and useful regional agricultural marketing intelligence

database that can be easily accessed by users across the Region.

11

Assessment, rationalization and harmonization of the activities, and pooling (where

possible) of the resources of the various regional agricultural institutions and

organizations.

Organization of a strategic plan for measures to enhance food safety and food security.

Industrial Sector

Identification and selection of key industries in which cross-border resource use can lead

to enhanced regional production, linkages can be exploited, regional production can be

enhanced and diversified, SMEs can find niches to successfully operate and in which

there is scope for public and private sector collaboratjon.

Development and implementation of a strategy to restructure the regional business

environment and benchmark successful businesses inside and outside of CARI COM.

Development and coordination across Member-States of Regional Standards, including

for protection of.the environment.

Services Sector

Enactment of Legislation and/or putting into operation administrative practices required

to eliminate restrictions.

Development of the infrastructural and support services required for a vibrant service

sector.

Identification and development of certain key service sector areas in which the Region

has or can develop a competitive advantage.

12

Air Transport Sector

Institutional strengthening of the Regional Air Safety Oversight System (RASOS)

Development of appropriate national and regional legislation and policies and securing

membership in the pertinent international agreements and complying with their

requirements.

Development and implementation of strategies for cooperation among regional airlines in

training, sharing of facilities and equipment and pooling of resources.

Promotion of investment opportunities in the sector..

Maritime Transport Sector

Elaboration of a plan for the development of a regional shipping industry.

Enhancement of cooperation amongst Maritime Administrations in Member States.

Improvement in cooperation on Maritime Safety and Protecting the Caribbean Sea.

Environmental Protection

Development of a Community Integrated Environmental Management Action Plan.

Organization of an Environmental Protection Promotional Program to pursue measures to

preserve, protect and improve the quality of the environment, such as the BEST program

in Barbados.

Development of an Environmental Research and Development Program, starting with a

baseline study to determine the current situation against which improvements can be

measured.

13

Development of a regional

environmental information system (such as

the

METROPOLIS Network in the EU) to store and analyze data on Member States.

Institutional strengthening and development of legislation, standards, and training.

Tourism

Implementation of the Caribbean Tourism Strategic Plan with emphasis on the Fund for

Sustainable Tourism.

Institutional strengthening of The Caribbean Tourism Human Resource Council

(CTHRC), the CHA and CTO.

Development of low cost marketing/promotional strategies for regional tourism.

Research & Development

Program to promote, reward, train and encourage the involvement of the private sector in

R&D for the development of new products and the generation of increased productivity.

Development of information systems to support global, regional and national R&D and

provide access and linkages between research institutions, Governments, private

businesses and individuals in all economic sectors across the Region.

Facilitation of R&D amongst Member States that maximizes the use of the Region's

biodiversity, abundant resources and other natural advantages.

Identification of sources of funding and the prov1s1on of assistance and training in

tapping these sources by UWI, CARDI and other regional research institutions and

researchers.

14

INFORMATION COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGY POLICY

In a Region comprised mainly of island states, Information and Communication Technology

(ICT) is probably now the single most important facilitator of integration. ICT was mentioned, if

somewhat briefly, in Chapter 3 of the Revised Treaty where its development was identified as

important in facilitating the free movement of goods, services, capital and the rights of

establishment in the Region. However, the Treaty provided few guidelines or objectives in terms

of policy and strategy.

The importance of ICT and the need for a detailed strategy has been clearly recognized by the

Heads of Government of CARI COM who mandated the CARI COM Secretariat to prepare, by a

participatory process, a CARICOM ICT Strategy. The focus of the strategy would be on ICT as

an instrument for strengthening connectivity to the rest of the world and as a means of fostering

greater prosperity and social transformation among Member States.

The Secretariat responded to the mandate of the Heads and the CARICOM/ICT Connectivity

Agenda 2003 was developed in which a strategy and plan for ICT development in the Region

were outlined. The approach revolves around three primary pillars - infrastructure, utilization

and content.

In February 2003, the CARICOM Ministers responsible for ICT signed the

Georgetown Declaration on CARICOM ICT Development 2003, which is to guide policymaking in this field in the Region.

Based on draft strategy documents and discussions with key persons across the Region, the

following four areas have been prioritized as critical for the implementation of the regional

strategic plan and the development of the ICT sub-sector. They are:

The development of appropriate regional ICT policies, including the development of

regional policies adopted by Member States that focus on a) the CSME trade and services

agenda; and b) Human and Social Development, especially as it relates to issues such as

poverty alleviation, the Digital Divide and Governance.

15

The development of regional training and capacity building programs, involving the

training of persons to understand and implement the policies that have been developed.

The development of a regional legal and regulatory framework, incorporating the

development of an appropriate legal framework to facilitate access and competition while

protecting the rights of all participants in the sub-sector.

The development and implementation of an overarching regional sensitization program to

increase the awareness of the public and private sectors, consumers, and the rest of civil

society.

The level and type of assistance required are detailed in the report.

HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT POLICY

The mandates in this area are stated in the 1997 Human Resource Development (HRD) Strategy

and the Measures are set out in Article 63 in the Revised Treaty.

The principal mandates as outlined in this HRD Strategy are to increase access to tertiary level

education; establish a Regional Accreditation Model; universal quality secondary education by

2005; the introduction of programs to achieve appropriate levels of competence in Spanish at

every level; the full enrolment of the pre-primary age cohort in early childhood education and

development programs; the development of computer skills at an early age as well as the

development of human resources to satisfy the requirements for groups of skilled agricultural

personnel at all levels, as outlined in the Revised Treaty.

Several activities have taken place across the various mandates in the core areas of education and

training. The CARJCOM Secretariat, in its coordinating and monitoring role, has facilitated

several activities. The University of the West Indies has undertaken certain activities and some

Member States have undertaken activities consistent with the mandates that can be replicated by

other Member States.

16

Some of the activities coordinated by the Secretariat include: the setting up of the Regional

Accreditation Agency and National Accreditation Bodies (NABs); the orientation of the

Technical and Vocational Education and Training {TVET) systems to adopt competency based

approaches; The Council on Human and Social Development's (COHSOD) approval of over 60

standards in 16 occupational areas as regional standards and the development of technology

education curriculum and units of instructions for the primary and lower secondary levels.

The main gaps identified with respect to the mandates are the development of appropriate

curricula to facilitate broad based education at the lower secondary level; the development and

implementation of standards for the delivery of Early Childhood Education; the integration of

new information and communication technologies into content (curricula), as well as

administration at all levels; the development and implementation of an appropriate technology

education curriculum . to lay a foundation for continuing education and technology; the

development of multilingual skills at an early age and the increased promotion of agriculture as a

career alternative for younger persons.

The requirements for filling these gaps were identified, as well as the level of assistance needed.

Priority areas and the type of assistance needed were also identified. Given the importance of

human resources to the implementation of the CSME, in most cases high priority was given to

the interventions required. However, in general, only moderate levels of financial and technical

assistance would be required to assist the Secretariat to better perform its coordinating role.

MACROECONOMIC FRAMEWORK

The Treaty provisions on Macroeconomic Coordination, the Harmonization of Monetary and

Fiscal Policies, and the promotion of a sound macroeconomic environment are insubstantial.

However, COFAP has recognized the potential disintegrative effects of the lack of

macroeconomic coordination, and has authorized work on rules and procedures for policy

coordination to be undertaken by a technical team, the main needs of which are for technical

assistance. Higher priority needs to be assigned to the macroeconomic aspects of the CSME.

17

Useful diagnostic work has been done on Fiscal Policy Harmonization. A Working Group on

Fiscal Policy has been established and donor support is actively being sought to develop a policy

framework, elaborate the legislative and institutional requirements, and assess the impact of tariff

reductions on government revenue.

CARICOM has already concluded a Double Taxation Agreement that is effective among several

Member States. A legal Draft of proposed Articles for a Protocol on a Harmonized Corporation

Tax Structure for Members of the Caribbean Community has been prepared, and is currently the

subject of consultations with national administrations.

COFAP has also mandated the preparation of a Harmonized Investment Framework and

appropriate regime for investment incentives. These prepar!1tions are now in progress, with

international donor support for regional diagnostic work and a study of international "best

practices" on investment policy, regulatory and administrative procedures, with a view to

drafting harmonized investment principles for CARICOM, to take the form of a CARICOM

Investment Code. The need for technical assistance is foreseen at the stage of intergovernment

negotiating and eventual adoption of the instrument under the legal procedures of each Member

State.

COFAP is m~ndated as well to adopt proposals for the establishment of Financial Infrastructure

Supportive of lnvvstments in the Community. The CCS aims to create a Protocol for the sector,

covering the banks and near-banks, and the insurance and securities industries. The broad areas

for possible harmonization have been identified. Work on tq.ese ;issues is at an ongoing stage o~

technical preparation. However, substantial more technical and legal work needs to be done

before a draft Protocol would be ready for inter-governmental negotiations.

The Revised Treaty est~blished a Regime for Disadvantaged Countries, Regions and Sectors. to

enhance their prospects for successful competition within the Community. For these purposes,

the Community established a Development Fund, among other measures. The modalities and

sources of finance for the operation of this Fund have not yet been determined. In the meantime,

there have been several cross-cutting initiatives that could have implications for the

establishment of the Fund. They include a proposal that has been under examination jointly by

18

the academic institutions with facilitating technical assistance and information sharing by the EU

in particular, could play a useful role in this respect.

PRIORITIZATION ACTION PLAN AND THE ROLE OF DONORS

The individual chapters indicated a priority ranking of projects within given areas. A more

complex issue is ranking priorities across different areas. For the latter purpose, the standard

methodology in this field was used.

It is based on establishing multiple weighted criteria

representing their individual salience to the Community, each associated with a relative value. It

is recognized that the use of this methodology has to be based, given that reliable quantification

is generally not available, to a large extent, on collective qualitative judgment. The criteria used

were urgency; short-term economic impact; long-term econqmic impact; critical building-block

function; opportunity cost; probability of attaining the objective. The weighting of these criteria

was undifferentiated.

A number of general conclusions were drawn from the analysis. They included, among others,

1) rankings across criteria were not highly correlated positively or negatively; 2) many areas fell

into the category of doubtful attainability in the foreseeable future; 3) an experimental cardinal

scoring suggested that areas with the highest ranking were Fiscal Policy Harmonization,

Community_Investment Policy, Tourism, Free Trade in Goods, Free Trade in Services, Free

Circulation, Competition Policy, Standards, and Public Education. The lowest scoring areas

were Industrial Policy, Monetary Union/Single Currency, Free Movement of Skills/Labor,

Intellectual Property, and the Development Fund. Other areas fell into the medium priority

category.

The Community has already benefited from substantial donor support, covering a wide range of

CSME-related projects.

This support has played a very significant role by complementing

Community resources.

Continued assistance will help the Community to cross the

implementation threshold in the priority areas.

Donor agencies are not expected to be part of the Community priority setting apparatus and

should not presume to determine what the Community's principles should be. They are welcome

20

the CDB and the IDB to set up a special fund for the restructuring of Caribbean economies; an

unimplemented decision to create a Regional Stabilization Fund; a proposal to set up a

Sustainable Tourism Investment Fund; a request to the CDB to elaborate the Projected

Investment Requirements for the Region's Infrastructural Development; a request to the CAIC to

develop a Program for the Transformation of Caribbean Economies; and a proposal that a

Regional Integration Fund should be established in the context of the Free Trade Area of the

Americas (FTAA).

The Community needs at this point in time to address both the issue of rationalizing/integrating

the various cross-cutting proposals that impinge on the establishment of the Development Fund,

as to define the prindples, as well as the legal and institutional context, under which a Fund

would operate, include its sources of funding.

It is noted that, unlike the situation in the EU where a Regional Development Fund is operated

with a similar purpose, the source of disparity in the distribution of benefits and costs would

mainly be of extra-regional origin. There may thus be some justification for external assistance

as the regional adjusts to integration into the world economy, an argument that also underpins the

proposal for a Regional Integration Fund in the context of the FTAA.

Monetary Union/Single Currency is not explicitly provided for the Revised Treaty, but is an

agreed aim of the Community, and a core feature of any single economic space. The approach

so far has been to monitor agreed macroeconomic parameters against pre-determined targets, so

as to gauge the extent of macroeconomic convergence, considered as the pre-condition . for

moving to a single currency. Attainment of the targets generally has been below expectation.

COFAP has accepted the recommendation of the Committee of Central Bank Governors that a

monetary union involving all CARICOM Member States is not attainable at this point in time,

but should remain a long-term goal. It proposed that in the interim the focus should be on

increasing public awareness and support of monetary union, and in establishing a greater

demonstration of political commitment. There is thus currently no agreement on the creation of

a common currency or whether any such currency should be fixed or floating. If this objective

- --·-

---·

· were to be advanced, some impetus beyond the Central Banks would be needed. The CCS and

19

CHAPTER II

INSTITUTIONAL AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK

(A)

BACKGROUND - THE TREATY OF CHAGUARAMAS

The Revised Treaty and the Protocols

The Treaty of Chaguaramas of 1973 was amended incrementally over a period of years by nine

Protocols, each of which addressed a specific area of concern. In July 2001, a Revised Treaty of

Chaguaramas, which provides the legal framework for the Community to move from a Common

Market to a Single Market and Economy, was signed by most Heads of Government · of ·

CARICOM in The Bahamas. The concerns of each Protocol now sit (largely unchanged) as

separate chapters within the Revised Treaty. As at July 2002, only two Member States i.e.,

Dominica and Montserrat had yet to sign the Revised Treaty.

In February 2002, the Heads of Government signed a Protocol for the Provisional Application of

the Revised Treaty. Montserrat is now the only Member State that has yet to sign the Protocol

and the Protocol on the Revised Treaty. The Protocol for the Provisional Application provides

Member States with the legal framework to apply the Treaty in a limited way.

The Revised Treaty imposes an obligation on each Member State to enact the revised Treaty into

national law. As of early July 2002, none of the Member States had ratified the Revised Treaty

nor had they enacted the Treaty into Domestic Law.

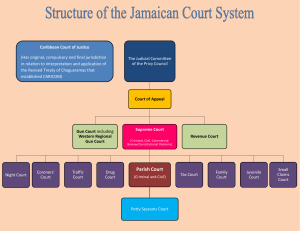

The Revised Treaty and the Caribbean Court of Justice

As the Community is an association of sovereign States, it was anticipated that the revised Treaty

could be subjected to as many interpretations as there are national jurisdictions, leading to legal

uncertainty. Such uncertainty would be bound to impact negatively on macro-economic stability

and the investment climate in the region. To overcome this potential problem the Caribbean

Court of Justice (CCJ) was invested with compulsory and exclusive jurisdiction in respect of

issues relating to the interpretation and application of the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas.

22

to contribute to methodologies that can be helpful in determining priorities, especially the

empirical analysis of prioritization. Donor agencies should participate in consultations with the

Community organs on ways and means by which they can assist and further the aims agreed on

and being pursued by the Community. Support programs among donor agencies should be

complementary, not competitive, disarticulated and overlapping. Coordination among donor

agencies should be for the purpose of delivering agreed assistance more effectively, transparently

and productively, not so as to better use their combined power to secure their own ends.

Donor agencies should be encouraged to offer assistance in areas where they have resources,

technology, expertise and experience that the Community lacks. Donor agencies and the CCS

should collaborate in defining the terms of reference of projects of cooperation and the

modalities under which they should be conducted, as well as in evaluations of the progress of

projects and their performance on completion. The Community for its part should recognize that

donors have a legitimate interest in ensuring that their resources are used cost-effectively and

transparently, and produce positive outcomes in respect of agreed objectives. It should set out its

priorities in a manner that is clear, reasoned and time-bound.

21