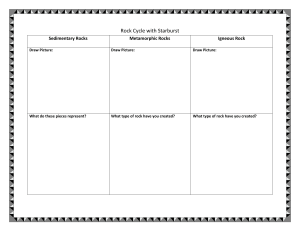

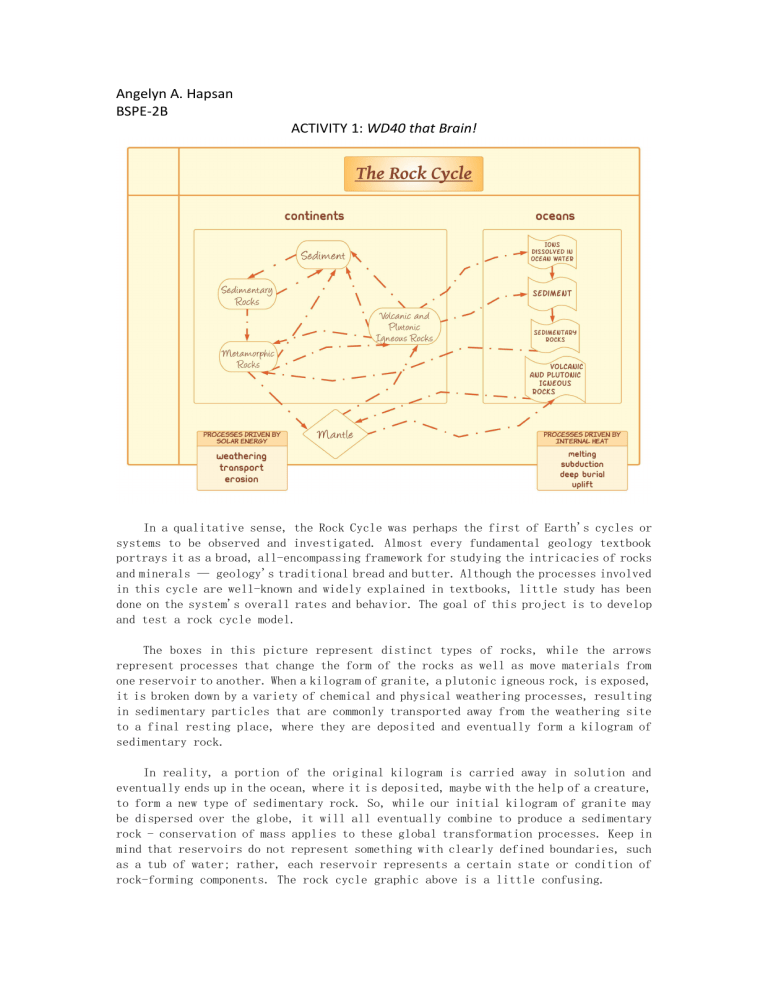

Angelyn A. Hapsan BSPE-2B ACTIVITY 1: WD40 that Brain! In a qualitative sense, the Rock Cycle was perhaps the first of Earth's cycles or systems to be observed and investigated. Almost every fundamental geology textbook portrays it as a broad, all-encompassing framework for studying the intricacies of rocks and minerals — geology's traditional bread and butter. Although the processes involved in this cycle are well-known and widely explained in textbooks, little study has been done on the system's overall rates and behavior. The goal of this project is to develop and test a rock cycle model. The boxes in this picture represent distinct types of rocks, while the arrows represent processes that change the form of the rocks as well as move materials from one reservoir to another. When a kilogram of granite, a plutonic igneous rock, is exposed, it is broken down by a variety of chemical and physical weathering processes, resulting in sedimentary particles that are commonly transported away from the weathering site to a final resting place, where they are deposited and eventually form a kilogram of sedimentary rock. In reality, a portion of the original kilogram is carried away in solution and eventually ends up in the ocean, where it is deposited, maybe with the help of a creature, to form a new type of sedimentary rock. So, while our initial kilogram of granite may be dispersed over the globe, it will all eventually combine to produce a sedimentary rock - conservation of mass applies to these global transformation processes. Keep in mind that reservoirs do not represent something with clearly defined boundaries, such as a tub of water; rather, each reservoir represents a certain state or condition of rock-forming components. The rock cycle graphic above is a little confusing.