Present Values Essays on Economics and Aspects of Indian Society

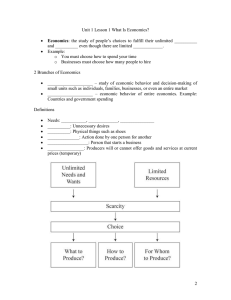

advertisement