The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at:

https://www.emerald.com/insight/2398-5364.htm

Mapping the key challenges and

managing the opportunities in

supply chain distribution during

COVID-19: a case of Myanmar

pharmaceutical company

Vimal Kumar

Supply chain

distribution

during

COVID-19

Received 10 January 2022

Revised 26 February 2022

Accepted 13 April 2022

Department of Information Management, Chaoyang University of Technology,

Taichung, Taiwan, and

Kyaw Zay Ya and Kuei-Kuei Lai

Department of Business Administration, Chaoyang University of Technology,

Taichung, Taiwan

Abstract

Purpose – This study aims to present a study on the supply chain process of a Myanmar-based

pharmaceutical company (named ABC Pvt. Ltd. in this study) that produces pharmaceutical products across

Myanmar and aims of bringing quality medical products and best care for Myanmar people’s health. The

study aims to identify the key supply chain challenges and manage the opportunities executed by this

pharmaceutical company to improve the supply chain process during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Design/methodology/approach – This work used a case study and conducted semistructured

interviews with the manager, senior managers and senior staff of the ABC Company to improve the supply

chain process and develop a comprehensive structural relationship to rank them to streamline the

uncertainties, real-time information and agility in a digital supply chain using grey relational analysis (GRA)

method.

Findings – From the data analysis and results, “Impact of political factor,” “Delay in import process” and

“Weak internet connection,” and “Weak knowledge of the use of digital platform,” “Poor information sharing

in online by employees” and “Information flow from top management to operational level” have been

identified as top and bottom three key challenges, respectively. “Inventory management,” “Selection of

transport method” and “Operational cost”, and “Marketing and brand Innovation,” “Online delivery of

products” and “E-commerce enablement (Launching applications, tracking system)” are identified as the top

and bottom three managing the opportunities, respectively.

Research limitations/implications – The findings of the study help to supply chain decision-makers

of the company in their establishment of key challenges and opportunities during the COVID-19 era. As a

leading company, it always tries to add value to its product through a supply chain system, effective

management teams and working with skillful decision-making toward satisfying the demand on time and

monitoring the supplier performance.

The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers, Associate Editor, and Editor-in-Chief

for their valuable comments and suggestions that helped to improve the manuscript.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or

publication of this article.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with

respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Journal of Global Operations and

Strategic Sourcing

© Emerald Publishing Limited

2398-5364

DOI 10.1108/JGOSS-01-2022-0002

JGOSS

Originality/value – The novelty of this study is to identify the key supply chain challenges and

opportunities by the GRA method to rank them, considering the case of Myanmar pharmaceutical

manufacturing company as a case-based approach to measuring its performance during the COVID-19

outbreak era. This work will assist managers and practitioners help to the company to provide optimal

services to its consumers on time in this critical situation.

Keywords Supply chain distribution, Pharmaceutical company, Challenges, Opportunities,

COVID-19, GRA method

Paper type Research paper

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced us to rethink our health-care systems, business models,

lifestyles and many other things, including supply chain management (Singh et al., 2022;

Bag et al., 2021b). Nowadays, the global supply chains (SC) have been badly affected by a

wide-ranging pandemic COVID-19 virus (Mayounga, 2021; Bag et al., 2021c). The outbreak

of this COVID-19 virus is the most overwhelming disturbance and has hugely impacted

global economic activities like manufacturing operations, SC and logistics and several

others (Goel et al., 2021; Nikolopoulos et al., 2021; Alam et al., 2021). We observed demand

and supply ripples; chaos and resonance effects propagated across global networks (Guan

et al., 2020). The various industries including different manufacturing and service sectors

are affected by the cause of this disease; these include the pharmaceuticals industry,

restaurant industry, energy industry, solar power sector, tourism, airlines, information and

electronics industry (Haleem et al., 2020; and Song et al., 2021). Many industries encountered

supply chain issues and had to manage and perform well as a result, while others, such as

pharmaceutical and technology industries, faced new challenges as well as opportunities.

According to Ayati et al. (2020), COVID-19 may be seen as a century’s opportunity for the

pharmaceutical industry; as it increases the demand for prescription medicines, vaccines and

medical devices. This industry has short- and long-term effects. Demand change, supply

shortages, panic buying and stocking, regulation changes can be seen as short-term impacts of

COVID-19 on the health market; while approval delays, moving toward self-sufficiency in the

pharm-production supply chain, industry growth slow-down and possible trend changes in

consumption could be seen as long-term impacts of COVID-19 on the health and pharmaceutical

market (Ayati et al., 2020). Several challenges were observed in the pharmaceutical industry’s

management of the pandemic, including difficulty meeting the demand for protective gear and

diagnostic testing facilities (Almurisi et al., 2020; Peeri et al., 2020). Likely to various other

companies, pharmaceutical companies are also bound to manufacture and distribute their

medicines and products on time. Every country in the world is facing supply chain challenges

like demand pattern, expenses, inventory management and customer response. In this study, our

target was to see the challenges and opportunities of Myanmar’s pharmaceutical companies.

According to Htut (2022), Myanmar is upgrading the health-care industry in the past decade by

increasing government spending on its medical services spending plan. Despite the fact that

Myanmar’s pharmaceutical expenditure has climbed at a rate of 13%–14% per year, from US

$391m in 2015 to US$409m in 2016 (World Health Statistics Report, 2021; Myanmar Health

Statistics Report, 2020). However, the nation is still experiencing a variety of obstacles and

challenges during COVID-19, such as inventory, availability of raw materials from the supplier

side, human resource (HR) and customer management concerns such as out of stock, supply to

match demand, inventory holding costs and credit management. In this current COVID-19 crisis,

the pharmaceutical industry supply chain can be scaled up quickly and flexibly to save lives

(Hsiao et al., 2020). As a result, during the COVID-19 epidemic, SC were more tightly compressed

to manage the process and control the upstream and downstream flows of supplies on time

(Handfield et al., 2020). Transportation facilities were severely impacted, but all small and large

pharmacies/stores simply ran out of stock during COVID-19 due to a constrained supply system

for raw materials and manufacturing, as well as panic buying among customers (Uwizeyimana

et al., 2021). Therefore, we focus to see these distribution challenges of this Myanmar-based

pharmaceutical company and try to manage the opportunities. For this, we derive the research

questions and research objective after that. The study objectives are to foster the identification

and prioritizing to smooth out the supply chain process and ensure timely distribution. With the

aforementioned factors in mind, this study concentrated on the following research questions:

RQ1. What are the essential key supply chain challenges and opportunities in a Myanmarbased pharmaceutical manufacturing company during the COVID-19 era?

RQ2. What method of preference ranking was used to organize them to manage and to

improve the supply chain performance?

The study proposed the following objectives:

Identifying the key challenges and opportunities for a pharmaceutical

manufacturing company’s supply chain during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Prioritizing the identified key challenges and opportunities using the grey relational

analysis (GRA) approach.

For the purpose of investigation, we adopted the multi-criteria decision making (MCDM)

technique for final data analysis. Under the MCDM techniques, we performed the GRA method.

The structure of this paper is divided into the following sections. The detailed literature

review is presented revolving around the COVID-19 outbreak, focused on different key

supply chain challenges and managing the opportunities of a pharmaceutical

manufacturing company in Section 2. Section 3 outlines the research methodology followed

by data analysis and results in Section 4. The discussions and findings with theoretical and

managerial implications are explained in Section 5, followed by the conclusions with

limitations and future scope in Section 6.

2. Literature review

2.1 COVID-19 and supply chain in pharmaceutical company

In today’s dynamic and globalized world, producing a product or service involves a complex

network of buyer-supplier links, not just the corporation (Jha et al., 2022; Jensen, 2017). Many

governments throughout the world have attempted to guarantee an appropriate supply of

key pharmaceuticals by limiting exports in reaction to the increased possibility of public

health problems as a result of the COVID-19 epidemic (Piatek et al., 2020). This crisis has

caused supply chain issues, but it has also caused widespread upheaval in the corporate

world, affecting everyone from small to large firms (Alhawari et al., 2021). The

pharmaceutical industry supply chain can be scaled up swiftly and flexibly to save lives in

this current COVID-19 crisis (Hsiao et al., 2020). The good relation among all supply chain

partners to manufacture and distribute on time. Especially, the pharmaceutical companies

are bound to manufacture and distribute their medicines and products on time. In any

circumstances, the SC are more tightly compressed to manage the process and control the

upstream and downstream flows of materials during the COVID-19 outbreak (Handfield

et al., 2020). The use of digital tools for seamless communication, together with substantial

developments in pharmaceutical manufacture and delivery (Sarkis et al., 2021). But all small

and big pharmacies/stores just ran out of stock during COVID-19 because of the limited

Supply chain

distribution

during

COVID-19

JGOSS

supply system of raw materials and manufacture and the panic buying practice among the

customers (Uwizeyimana et al., 2021). Data analytics in pharmaceutical SC has sparked a lot of

attention in recent years because it has the potential to improve health-care product supply and

management by harnessing data provided by current technologies (Nguyen et al., 2021; Bag et al.,

2021b; Kaupa and Naude, 2021). But the pharmaceutical companies face different key supply

chain challenges and the need to manage the opportunities to provide optimal services to their

customers. In this situation, the businesses must concentrate on seeking continuous improvement

in production efficiency and effectiveness of manufacturing operations and distribution (Verma

et al., 2021; Chowdary and George, 2012).

The pharmaceutical market is taken into consideration as a major perspective in the healthcare sector (Nasrollahi and Razmi, 2019; Singh et al., 2016) and it can be stated that its significant

contribution to society has been doubled during the COVID-19 outbreak. The current situation is

still pandemic time (WHO, 2021), and the UK has restarted lockdown rules recently due to such a

rage spread of the new COVID variant, Omicron (The Guardian, 2021). COVID-19 disrupts the

world of work and reshuffles the outlook of factories (Ramanathan et al., 2021; Khan et al., 2021;

Al-Mansour and Al-Ajmi, 2020; Akintokunbo and Adim, 2020). It has lengthened the supply

chain resilience to the limited margin by assessing the agility and flexibility of the supply chain in

the enterprises including pharmaceutical business (Handfield et al., 2020; Sarma et al., 2021;

Karmaker and Ahmed, 2020; Piprani et al., 2020; Ivanov, 2020). However, the firms have figured

out how to improve the resilience of their global SC in the face of severe calamities (Ivanov and

Das, 2020; Modgil et al., 2021). It has changed typical work-related mobility to digital work

(Taylor and Taylor, 2021). Digital evolution has caused local and international pressures on

typical business leaders through many restrictions (Ivanov and Dolgui, 2021; Ahmad and John,

2021; Parmata and Chetla, 2021). However, it provides several advantages to supply chain

players such as reducing work processing time, faster online tracking, quick information sharing

and order forecast (Mishra et al., 2021; Pyun and Rha, 2021). As the results of that existing

literature indicate the effects of COVID-19 spread and regulatory rules are significantly testing

the use of business strategies under uncertainties, real-time information and supply chain agility

of pharmaceutical companies.

2.2 Uncertainties

The pharmaceutical factory is a kind of industry that is full of challenges related to uncertainties

in the world (Schumacher et al., 2020). Among three types of uncertainty related to sustainable

supply chain; task uncertainty, source uncertainty and supply chain uncertainty (Busse et al.,

2017; Jauhar et al., 2021; Pathak et al., 2020; Verma et al., 2020), the challenges happening in this

sector are both probabilistic and deterministic (Tripathi et al., 2019). The demand for medicine

supply is uncertain because it can be influenced by seasonal changes, and the costs for medical

products can be uncertain due to the regulatory rules (Franco and Alfonso-Lizarazo, 2020). One of

the effects of COVID-19 is serious delay not only in production but also in the import and export

process (Butt, 2021; Kumar et al., 2022). Excessive disruption and delay in the supply chain can

increase the rate of mortality and morbidity of the patients (Ahmad and John, 2021), and supply

chain disruption may impact tremendously on business performance and its capacity to survive

(Carbonara and Pellegrino, 2018; Abdolazimi et al., 2021). Singh et al. (2016) also urged the facts

related to uncertainty, such as everchanging trends of product innovation, the short life cycle of

the product, continuous technology improvement, competitive global business market, high

production cost and time-consuming clinical trials for product development. The severer the

inventory shortage locally and internationally, the more cautious the governments and business

leaders are Schumacher et al. (2020). Such uncertainties can lead to problems in storage and

warehouse space (Agyabeng-Mensah et al., 2020). Therefore, decision-making in uncertain

conditions is a complex issue evolving a variety of functions of information sources throughout

the supply chain (Kumar et al., 2021).

2.3 Real-time information

As the supply chain has material flow and information flow, information sharing is

considered as an effective tool for facilitating the supply chain responsiveness, and it is a

forerunner which goes first before material flow (Harrison et al., 2014). However, the

importance of real-time information seems to have been ignored because it is very scanty

literature while there are many research studies related to supply chain challenges and

performances during a pandemic. Information is flowing from and to upstream and

downstream while the material is going from upstream to downstream only (Porter, 1985).

Information analysis is also considered a critical success factor in total quality management

(Duggirala et al., 2008) as cited in Kumar and Sharma (2017). Supply chain performance

from raw material through manufacturing, warehousing and distribution until the end user

can effectively be performed through information access and information technologies

(Mukhsina et al., 2021; Pansare et al., 2021; Agyabeng-Mensah et al., 2020; Tripathi et al.,

2019; Kumar et al., 2017). Right time distribution is one of the factors to fulfill customer

satisfaction and prioritizing request (Ershadi and Ershadi, 2021). The use of environmentalfriendly technologies and green packaging can also lead to customer satisfaction

(Agyabeng-Mensah et al., 2020; Bag et al., 2020a; Nantee and Sureeyatanapas, 2021). During

a pandemic, some factories are trying to boost the existing supply chain by raising

manufacturing and distribution abilities (Park et al., 2020). Enhancing distribution efficiency

through financial metrics, effective cost reduction can be performed through various stages

in the supply chain (Shah and Sing, 2001 as cited in Tripathi et al., 2019). This can help

product pricing, which has become a major challenge during the COVID-19 outbreak

(Ershadi and Ershadi, 2021) because demand uncertainty, performances of competitors,

governmental actions, bargaining power of suppliers cause high product pricing (Porter,

1985 as cited in Singh et al., 2016). As the consequence, the scholars indicate real-time

information can be concerned as a crucial role for product distribution, production process,

supply chain agility, etc.

2.4 Agility

In an agile supply chain, factors such as quality, velocity, flexibility and responsiveness

throughout the supply chain are major abilities for customer demand and market needs

(Singh et al., 2019; Mehralian et al., 2015). However, during a pandemic, it is very difficult to

ensure an adequate amount of stock to promise the capability and to perform for meeting the

business promises (Butt, 2021). Pandemic has forced the local authorized people to prohibit

imports with several regulations, and this also causes their struggle to hold a particular

number of exports (Butt, 2021). The geographical restriction is one of the factors badly

affecting business promises, supply chain agility and high logistics cost (Schumacher et al.,

2020; Ivanov, 2020; Bag et al., 2020b). The further the location between warehouse, factory

and retailers, the more consuming the cost for logistics and the more challenging it to choose

the transport methods (Agyabeng-Mensah et al., 2020). Here, sustainable logistics practices

such as the application of environmental-friendly vehicles, developing recycling processes,

low-carbon machinery or some other sustainable products can raise the company image and

brand value creation (Nantee and Sureeyatanapas, 2021; Sharma et al., 2021a; Sharma et al.,

2021b; Bag et al., 2021d; Verma et al., 2022a; Pathak et al., 2021; Saglam et al., 2020; Yadav

et al., 2020; Chauhan et al., 2020; Fratocchi and Di Stefano, 2019). On the other hand, supplier

performance and high price from the supplier side has also become the main concerns for a

Supply chain

distribution

during

COVID-19

JGOSS

company (Jha et al., 2022; Butt, 2021; Do et al., 2020; Andersen et al., 2019) because supplier

and company are interconnected as business to business (Gupta et al., 2018). Government

tax increment also raises manufacturing costs on the supplier side (Moktadir et al., 2018).

Moreover, market fluctuation includes panic buying due to the changes in preferences for

certain commodities (Abdolazimi et al., 2021). Panic buying will go up over a period of time

because demand-supply will be low while at the same time, new merchandising by

consumers is high (Ramanathan et al., 2021). To meet the market demand, supply chain

players use several ways including postponement orientation is one of the crucial factors

through downstream, upstream and distribution for mitigating demand uncertainty (Wu

et al., 2019; Carbonara and Pellegrino, 2018; Costantino et al., 2012). Postponement is defined

as a method of locomoting one or more functions to a later spot in the supply chain

(Abdallah and Nabass, 2018). Distribution postponement is functioned by the manufacturer

to hold the stock until the order placement is confirmed (Bagchi and Gaur, 2017).

Postponement strategy seems to have been a vital role in the business supply chain during

pandemics (Wang et al., 2022; Johnson and Haug (2021). The evidence reveals that market

fluctuation during pandemics causes severe and dramatic supply chain ramifications.

2.5 Key supply chain challenges and managing the opportunities

In this competitive supply chain age between businesses, managing the challenges is a major

challenge for supply chain players and researchers (Abdolazimi et al., 2021; Franco and AlfonsoLizarazo, 2020). To manage the challenges, many researchers have explored and proposed several

means and models to help supply chain practitioners. Schumacher et al. (2020) and Sharma et al.

(2021c) suggested setting up the inspection system even in the upstream and downstream supply

chain to avoid cost-consuming backward processes and reverse logistics. In the pharmaceutical

supply chain, expired medicines can be delivered back to the manufacturing company and can be

reused (Xie and Breen, 2012, as cited in Singh et al., 2016). They also pointed out the usefulness of

agile process management because a broad-ranging supply chain with many stakeholders can

rapidly lead to constrictions in the chain. Manuj and Mentzer (2008) also discovered six strategies

for managing risks such as postponement, speculation, hedging, control/share/transfer, security

and avoidance. Ivanov and Dolgui (2020), Fierro Hernandez and Haddud (2018) and Kurniawan

et al. (2017)’s study pointed out that risk management culture positively facilitates supply chain

visibility and supplier development, a common technique in Indonesia firms on supply chain

responsiveness. Besides, Taylor and Taylor’s (2021) study indicated that advanced digital

infrastructure might be better prepared for global nations to adapt the societal disruptions such

as the COVID-19 outbreak.

Bag et al. (2021a) and Saglam et al. (2020)’s study findings showed that supply chain

responsiveness and resilience, which are risk-mitigating tactics, positively deal with supply chain

risk management (SCRM). While managing opportunities, collaboration should not be ignored,

and regarding this, Giri and Manohar’s (2021) research indicated that private blockchain-based

collaboration and public blockchain-based collaboration support behavioral intention to use. In the

collaboration phase, information flow is quite important for data transparency, real-time

information, accurate data and the use of informative technology among all stakeholders (Mishra

et al., 2021; Nantee and Sureeyatanapas, 2021; Abdallah and Nabass, 2018; Haque and Islam, 2018).

Since the supply chain is a series of activities evolving many stakeholders from operational level to

top management, effective human resource management can derive its organization to become

more ambitious and valuable in their market to provide revenue prosperity and social benefits for

their stakeholders (Anlesinya and Susomrith, 2020). However, pandemic creates HR bundles, e.g.

payroll and thus, the company applies some HR strategies such as deferment of salary increment,

nonpayment leave and temporary pay reduction (Adikaram et al., 2021; Verma et al., 2022b).

Many scholars have revealed such a surge of COVID-19 outbreaks in the government

sector. Respective governments are also struggling in handling the COVID-19 rules and

regulations (Jamaani, 2021). This study’s research location is Myanmar which has been

experienced more than 70 years of civil war (Quah, 2016) added by the COVID-19 outbreak

and military coup in 2021. Although the nation’s economy, education, health-care sectors

were calm and can well be handled by a democratic civilian government before the military

coup in February 2021, all these sectors were seemed to have interrupted, destroyed and

some are being stopped due to the military coup (VOA, 2021). In this situation, threatened by

a terrible national economy, business enterprises are trying to survive in their way.

Although Myanmar’s business field has many restrictions especially trade, import process

and customs, most of the businesses are using cloud services for their digital work during

pandemics (Oxford Business Group, 2020). However, after a military coup, the country has

been beaten hardly by a wrecking cash shortage, money inflation, increase of internet

service charges and so on (Deutsche, 2021). All enterprises including pharmaceutical

enterprises suffer such a volume of difficulties in sales, import process, customs clearance,

transportation, lockdown, employee health concern and brand innovation as well. The study

investigates the challenges being faced in Myanmar pharmaceutical product distribution

companies and strategies being applied by business players in that company for mitigating

or solving challenges through the three supply chain dominants; uncertainty, real-time

information and agility.

To clarify the actual research scope of the study, several research gaps has been

identified after the review of available literature to the concern of supply chain distribution

with supplier performance and its challenges and opportunities of Myanmar-based

pharmaceutical company during the COVID-19 outbreak. The following points emphasize

and highlight the research gaps derived from the literature review:

COVID-19 disrupts the world of work and reshuffles the outlook of factories

(Ramanathan et al., 2021; Khan et al., 2021; Al-Mansour and Al-Ajmi, 2020;

Akintokunbo and Adim, 2020). Hence, it affects the serious delay not only in

production but also in the import and export process (Butt, 2021). It is noted that

production and distribution should be maintained and managed.

Finding the way of transport between warehouse, factory and retailers are not so

easy for logistics and the more challenging to provide essential things (like

medicines) on time and conveniently (Agyabeng-Mensah et al., 2020). In the case of

Myanmar-pharmaceutical companies, getting away from these problems and

managing the opportunities is seen as a priority.

The pharmaceutical industry supply chain can be scaled up swiftly and flexibly to

save lives in this current COVID-19 crisis (Hsiao et al., 2020). Hence, the SC are more

tightly compressed to manage the process and control the upstream and

downstream flows of materials on time during the COVID-19 outbreak (Handfield

et al., 2020). The transportation facilities were affected badly, but all small and big

pharmacies/stores just ran out of stock during COVID-19 because of the limited

supply system of raw materials and manufacture and the panic buying practice

among the customers (Uwizeyimana et al., 2021).

To sum up, this study was intended to fill gaps regarding the key supply chain

challenges and manage the opportunities executed by this pharmaceutical company

to improve the supply chain process during the COVID-19 outbreak and to establish

its rank using the GRA technique in the literature.

Supply chain

distribution

during

COVID-19

JGOSS

3. Research methodology

3.1 The case study

The Myanmar-based company ABC founded in 1993, is a company that distributes

pharmaceutical products across Myanmar with the aim of bringing quality medical

products and best care for Myanmar people’s health. With sustainable development, the

company has become one of the leading pharmaceutical distribution companies in Myanmar

by striving to cater to a local market with quality medical products. More than 27 years of

good reputation in the Myanmar medical market has proved that the company has been

developed on a concrete foundation of business performance of modern sales and sound

marketing strategies.

Its head office is located in Yangon city, business city of Myanmar, and other major

branch offices are in Mandalay city, Pyae city, Mawlamyaing city, etc. The performance and

sales targets are generally and continually analyzed to provide optimal services to its

consumers. As a leading enterprise, it owns an effective logistics and supply chain

management system starting from suppliers through warehousing, transportation and

distribution until the end consumers plus building a good relationship with its dealers,

hospitals and customers around the country.

Its upstream supply chain strategy is to deal with dealers directly and thus, its sales and

marketing employees travel to the whole nation monthly for regular and better relationship

building with dealers (Yildiz Çankaya, 2020). Besides, it also usually participates in

community activities especially medical seminars and conferences as the main sponsor.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, it also suffers negative effects on its marketing and

brand innovation, sales, supply chain system, operational cost, inventory management, etc.

Moreover, the very complicated political conflicts of Myanmar also cause additional heavy

pressures on its standing out in the business field. Ever-changing economic rules and

regulations by authorized people cause lots of delays in the product import process, customs

clearance process, geographical restrictions of logistics and so on because it is a distribution

company and most of their products are imported from foreign countries, especially Asian

countries. Besides, Asian countries are also suffering side effects of the COVID-19 outbreak

and facing a huge number of struggles in production. Thus, these two factors, the COVID-19

outbreak and Myanmar’s political instability have doubled problems, interruptions,

challenges and difficulties for the ABC Pvt. Ltd. company.

To overcome these challenges and to reduce the COVID-19 pandemic, the decisionmakers (DMs) of ABC Pvt. Ltd. have decided to identify them and propose and develop

opportunities to manage the supply chain operations. The seminal paper of Eisenhardt

(1989) has inspired and encouraged researchers to investigate a wide range of topics to

develop concepts and theories based on case studies (on various challenges and

opportunities of the pharmaceutical company supply chain). To explore and prioritize them,

a multicriteria decision-making methodology has been used in this work. This work focuses

on qualitative and quantitative methodologies based on semistructured interviews, and

observational methods are used in the Myanmar pharmaceutical company. At the beginning

of this process, we identified some challenges and opportunities and formulated a set of

questions to get the perspectives of various levels of target responders from the top

management of the company. The 11 professionals from the various department such as

logistics, audit, accounting, human resource and business division are among those who

contributed passionately. These responders have good experience and are also pioneers in

their company. The demographic details of the respondents are summarized in Table 1.

We identified 11 DMs among the respondents following the collection of responses. From

the current literature and semistructural interview, a total of 20 key challenges and twenty

Profile

Classification

Gender

Male

Female

21–30

31–40

41–50

Above 50

Manager

Supervisor

Senior Manager

Executive

Diploma

Bachelors

Post Graduate

Managerial

Technical

1–5 years

6–10 years

11–15 years

16 and above years

1–5 years

6–10 years

11–15 years

16 and above years

Warehouse

Logistics

Audit

Accounting

Human Resource

Business Division

Age

Designation

Education

Current Job Position

Current Organization Tenure

Overall Work Experience

Department of Respondents

Count

4

7

4

6

1

0

6

4

1

0

1

8

2

9

2

7

2

1

1

0

4

3

3

2

2

1

2

2

2

opportunities are identified, shown in Table 2. The flowchart of the current study’s suggested

research effort is shown in Figure 1. The questionnaire has been designed in Appendix.

3.2 Grey relational analysis method

In the grey system theory, “grey” refers to primitive data with poor, incomplete and

uncertain information, and the “grey relation” is the incomplete information relation among

these data (Chatterjee and Chakraborty, 2014). GRA technique is suitable for resolving

problems involving complex interrelationships between many components and variables

(Kuo et al., 2008; Tosun, 2006) called multiple characteristics and criteria and determining

grey relational grades (Chan and Tong, 2007; Zeng et al., 2007). Hamzaçebi and Pekkaya

(2011) define a grey relational generation as the calculation of grey relational coefficients to

address uncertain systematic issues with only partially available information. The GRA

approach is frequently used, implemented and computed to choose and rank performance

alternatives rather than relying on expert judgment. In recent studies, Yi et al. (2021) used

GRA to assess the sustainability of 15 Chinese subprovincial cities to promote sustainable

development, while Niu et al. (2021) used GRA in a Taguchi-based methodology to optimize

air-jet supply. Most MCDM approaches involve generating multidimensions of selected

criteria to one dimension of alternative and considering multiple dimensions of criteria with

multidimensions of alternatives to determine their quality and solve various selection

Supply chain

distribution

during

COVID-19

Table 1.

Demographic details

of the respondents

Agility

Real-time information

Storage problem (C1)

Uncertainty

Excessive disruption and delay in inventory storage may longer

store the stock in warehouse. This may lead to storage problem

Geographical restrictions due to COVID-19 outbreak cause serious

delay in import process

Distribution postponement is performed by the product producer

to control the inventory until the order is confirmed

Pandemic prohibits tend to concern of supplier performance

Government tax increase and high price from supplier side lead to

rise the product pricing

Panic buying is caused by an anxious mindset

Descriptions

Agyabeng-Mensah et al.

(2020), Butt (2021),

Costantino et al. (2012),

Wu et al. (2019),

Carbonara and Pellegrino

(2018), Bagchi and Gaur

(2017), Gupta et al. (2018),

Abdolazimi et al. (2021)

Sources

(continued)

During pandemic, typical workplace has been changed to online

workplace. Some employees are struggle in that condition due to

the lack of technical knowledge of digital software and application

Impact of political factor (C8)

Myanmar’s political instability influence, interrupts and destroys

supply chain process

Poor information sharing in online by

Some employees hesitate for quick information sharing

Mishra et al. (2021), Pyun

employees (C9)

and Rha (2021), Nantee

and Sureeyatanapas

Weak knowledge of the use of digital

Some employees have poor technical skill of the use of software

(2021), Abdallah and

platform (C10)

and app

Information flow from top management Information access is very crucial for data transparency, real-time Nabass (2018), Deutsche

(2021)

to operational level (C11)

information and accurate data among all stakeholders

Weak internet connection (C12)

Political instability causes the increase of internet bill charges in

Myanmar

Prioritizing requests (C13)

Due to the COVID-19 outbreak, volume of order is received from

Ershadi and Ershadi

many customers. Systematic order request priority can fulfill

(2021), Agyabeng-Mensah

customer satisfaction

et al. (2020), Nantee and

Customer satisfaction on business

Punctual distribution, meeting demand, the use of environmental- Sureeyatanapas (2021),

Singh et al. (2016),

promises (C14)

friendly technologies and green packaging can also lead to

Adikaram et al. (2021),

customer satisfaction

Product pricing (C15)

Demand uncertainty, performances of competitors, governmental Schumacher et al. (2020),

actions, bargaining power of suppliers cause high product pricing Park et al. (2020)

Surging demand exacerbated by panic

buying and excessive stockpiling (C6)

Difficulties in transition from face-toface work type to digital work (C7)

Suppliers’ performance concerns (C4)

Higher cost from supplier side (C5)

Demand postponement (C3)

Delay in import process (C2)

Challenges

Table 2.

Relevant literature

review

Indicator

JGOSS

Indicator

Uncertainties

Indicator

Due to COVID-19 infection to employees, operational disruption

occurs

Pandemic creates HR bundles, e.g. payroll, and thus, company

applies some HR strategies such as deferment of salary

increasement, nonpayment leave and temporary pay reduction

Geographical restriction is a factor negatively impacting on

business promises, supply chain agility and high logistics cost

COVID-19’s new variant Omicron is currently emerging around

the world, and on the other hand, businesses have got covid

experiences since 2020. Using these experiences, it is a crucial

thing to build future plans

During pandemic, some businesses boost up existing supply chain

by raising manufacturing and distribution abilities

Descriptions

Due to pandemic and geographical restrictions, it is challenging to

select transport method based on high price, time allowance and

mode of method

High demand tends to high order frequency

Due to high demand, number of clients might increase in

pharmaceutical market

Risk management culture positively facilitates to supply chain

visibility and supplier development

As a pharmaceutical company, inventory management plays a

vital role

The severer the inventory shortage, the more cautious the

governments and business leaders

High price from supplier and other costs evolving logistics lead to

increase high operational cost

Company has to work under the policy enacted by authorized

people

Operational disruption due to COVID

infection to employees (C16)

Salary of employee (C17)

Regulatory frameworks and policies

(MO7)

Operational cost (MO6)

Inventory management (MO5)

Planning and risk management (MO4)

Client’s orders frequency (MO2)

Client’s quantity (MO3)

Managing opportunities

Selection of transport method (MO1)

Punctual distribution (C20)

Geographical restriction on logistical

flow (C18)

Perspective on future plan while

emerging new COVID Omicron variant

(C19)

Descriptions

Challenges

(continued)

Sources

Agyabeng-Mensah et al.

(2020), Kurniawan et al.

(2017), Schumacher et al.

(2020), Franco and

Alfonso-Lizarazo (2020)

Sources

Supply chain

distribution

during

COVID-19

Table 2.

The use of pandemic experience for

business development (MO20)

Reverse logistics (MO19)

Company-supplier-customer

relationship management (MO14)

Marketing and brand innovation

(MO15)

Effective utilization of human and

equipment (MO16)

Online delivery of products (MO17)

E-commerce enablement (MO18)

The ability to meet promised delivery

date (MO8)

Integration/collaboration of activities

across the supply chain through realtime information sharing (MO9)

Providing information in a timely

manner (MO10)

Providing the training for the use of

digital apps and software for on time

information (MO11)

Adoption of new technologies that can

help distributors provide real-time

updates (MO12)

Support service (MO13)

Information

Agility

Challenges

Table 2.

Indicator

This is a branch of distribution channel to use online couriers

During pandemic, companies require to procure new e-commerce

software or app to facilitate work process

In pharmaceutical supply chain, expired medicines can be sent

back to factory and can be reused

Pandemic has entered into almost two years. Business enterprises

have got pandemic experiences which can be used for future

business development

To enhance employees’ skills, additional training is needed to be

provided

Relationship management is an essential tool among suppliers,

customers and company

Brand innovation is considered as a

During pandemic, enterprises adopt to survive in a competitive

market, e.g. Zoom application

Some employees possess poor technical skills of using digital

applications. Thus, additional is provided

Information transparency and quickness help to meet business

promises

In collaboration phase, information flow is quite important for

data transparency, real-time information, accurate data and the

use of informative technology among all stakeholder (

Real-time information resides the core of material supply chain

Descriptions

Giri and Manohar (2021),

Singh et al. (2016)

Pyun and Rha (2021),

Mishra et al. (2021),

Nantee and

Sureeyatanapas (2021),

Abdallah and Nabass

(2018)

Sources

JGOSS

Supply chain

distribution

during

COVID-19

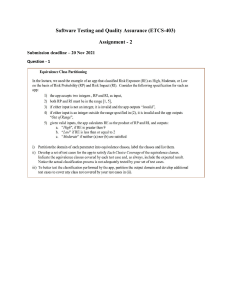

Extensive Literature Review and Identify

the Challenges and Opportunities

Form Decision Making

Team

Determine the Criteria

No

Decision

Hesitancy

Yes

Establish a Grey Relation

Generation Matrix

Normalize the Decision

Matrix

Define the Reference Sequence

Find the Deviation Sequence

Values of Decision Matrix

Calculate the Grey

Relational Coefficient

Compute the Grey

Relational Grade

Determine the preference

Order

difficulties for this decision model. Further, it also assesses the performance of grey

relational generation, a comparative sequence. A reference sequence (ideal target

sequence) is constructed based on this sequence, and the grey relational coefficients

between all the comparability sequences and the reference sequence are then

computed. After that, the grey relational grade is calculated using these coefficients.

If a comparability sequence translated from an alternative has the highest grey

relational grade between the reference sequence and itself, that alternative is the best,

and the last is the worst. The GRA method’s procedural steps are listed below

(Chatterjee and Chakraborty, 2014; Lotfi, 1995).

3.2.1 Step 1: Grey relation generation (normalization). When the units of several

selection criteria differ, normalizing, also known as grey relational generation or data

preprocessing, is necessary to convert all of the performance values for each choice into a

comparable sequence. If there are m options and n criteria in a decision-making problem, the

ith alternative can be written as Yi = (yi1, yi2,. . ..,yij,. . .,yin), where yij is the performance

value of criterion j of alternative i. Using equation (1) or equation (2), the term Yi may

be converted into the relevant comparability sequence, Xi = (xi1, xi2,. . .,xij,. . .,xin) (2). The

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the

proposed research

work

JGOSS

decision matrix can be normalized using equation (1) if the criterion is helpful, i.e. a greater

value is desirable. Equation (2) can be used to normalize nonbeneficial criteria.

h

i

ðyij Þ min yij ; i ¼ 1; 2; . . . ; m

(1)

xi;j ¼ max yij ; i ¼ 1; 2; . . . ; m min yij ; i ¼ 1; 2; . . . ; m

h

i

max yij ; i ¼ 1; 2; . . . ; m ðyij Þ

xi;j ¼ max yij ; i ¼ 1; 2; . . . ; m min yij ; i ¼ 1; 2; . . . ; m

(2)

3.2.2 Step 2: Define the reference sequence. The performance numbers will be between 0

and 1 after the grey relation generating operation. If the value xij, which is normalized using

the grey relation generating technique, is equal to or nearer to 1 than the value of the other

alternative for a criterion j, it signifies that alternative I’s performance is the best for that

criterion j. As a result, if all of an alternative’s performance numbers are close to or equal to

1, it will be the best decision. The reference alternative is defined as X0 = (x01, x02,. . .,x0j,. . .,

x0n) = (1,1,. . .,1,. . .,. . .,1) and seeks to discover the alternative with the most similar

comparability sequence to the reference sequence.

3.2.3 Step 3: Calculate the grey relational coefficient (W). To establish how close xij is to

x0j, the grey relational coefficient is used. Equation (3) can be used to compute the grey

relationship coefficient. The greater the value of W, the closer xij and x0i are to each other.

Wðx0;i ; xi;j Þ ¼

Dmin þ z Dmax

ð for i ¼ 1; 2; . . . ; m and j ¼ 1; 2; . . . nÞ

Di;j þ z Dmax

(3)

where W (x0,i, xi,j) is the grey relational coefficient between xi,j and x0,i, Di,j = jx0,j xijj

Dmin= min {Di,j,1,2,. . .,m; j = 1,2,. . .,n}

Dmaxn= max {Di,j,1,2,. . .,m; j = 1,2,. . .,n}and z is the distinguish coefficient ( z [ [0,1]),

generally taken as 0.5.

The purpose of the distinguishing coefficient is to expand or compress the range of the

grey relational coefficient.

3.2.4 Step 4: Compute the grey relational grade. After calculating the grey relational

coefficient W (x0i, xij), the grey relational grade can be calculated using the following

equation:

Cðx0 ; xi Þ ¼

n

X

wj Wðxi ; xij Þ ð for i ¼ 1; 2; . . . ; mÞ

(4)

j¼1

where

n

X

wj ¼ 1

j¼1

and the weight of the jth criteria, wj, is determined by the decision-maker. The level of

correlation between the reference sequence and the comparability sequence is shown by the

grey relational grade. If an alternative’s comparability sequence has the greatest grey

relational grade with the reference sequence, it signifies the comparability sequence is the

most similar to the reference sequence, and that option is the best choice.

4. Data analysis and results

For the research questions given in this research paper, there are 11 decision-makers (DMs)

who belong to top management and help ABC Pvt. Ltd. with their best practices. These 10

DMs (DM1 to DM11) each have a good experience. From the source of literature and

semistructural interviews with these identified decision-makers, we prepared a list of 20 key

supply chain challenges and 20 opportunities implemented by this pharmaceutical company

to manage the supply chain process during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, the key supply

chain strategies have been analyzed by using an MCDM technique GRA to find out their

priority significance in the context of the pharmaceutical company. Based on DMs’ (DM1 to

DM11) experience, scores have been composed for all these key supply chain challenges.

Table 3 represents the scores of the decision matrix for the individual key supply chain

challenges.

The main process of GRA methodology begins by using Step 1, i.e. translating the score

of all the key supply chain challenges into a comparability normalized sequence. The

normalized values of this decision matrix are given in Table 4.

Based on this normalized sequence, and by using Step 2, reference sequences are

determined and presented in Table 5. Using Step 3, the grey relational coefficients between

all the comparability sequences and the reference sequence are computed and presented in

Table 6. Now using Step 4, the grey relational grade between the reference sequence and

every comparability sequence is calculated and presented in Table 7. The highest the grade

the best will be the choice, so accordingly, based on this calculated grey relational grade, the

ranking of these key supply chain challenges that identified and managed the supply chain

Supply chain

distribution

during

COVID-19

S. N. Key supply chain challenges DM1 DM2 DM3 DM4 DM5 DM6 DM7 DM8 DM9 DM10 DM11

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Min

Max

C1

C2

C3

C4

C5

C6

C7

C8

C9

C10

C11

C12

C13

C14

C15

C16

C17

C18

C19

C20

5

4

3

4

4

2

4

5

4

4

4

5

4

3

4

5

3

4

4

4

2

5

4

4

3

3

3

3

4

4

2

2

2

4

4

3

3

4

5

4

4

4

2

5

4

5

5

4

4

3

4

5

3

4

2

4

3

4

5

4

4

5

2

4

2

5

4

5

4

5

5

3

4

5

4

4

2

5

3

4

5

5

5

5

2

4

2

5

2

5

5

5

5

5

4

5

4

4

2

5

2

2

5

5

2

5

2

5

2

5

4

5

5

5

3

5

4

3

2

2

4

3

4

4

2

5

4

4

4

4

2

5

3

4

5

5

5

4

3

5

4

4

3

5

3

3

4

4

2

4

2

4

2

5

3

5

5

5

5

4

5

5

3

3

3

5

3

5

5

3

3

5

4

5

3

5

3

5

5

5

5

4

5

5

3

3

3

5

3

4

5

3

3

5

3

5

3

5

4

5

5

4

5

5

5

5

2

2

3

5

4

4

4

5

4

4

4

4

2

5

3

4

4

4

4

3

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

5

5

4

3

5

Table 3.

The scores of the

decision matrix (for

challenges)

Challenges

C1

C2

C3

C4

C5

C6

C7

C8

C9

C10

C11

C12

C13

C14

C15

C16

C17

C18

C19

C20

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Min

Max

Table 4.

Normalized values of

decision matrix (for

challenges)

S N.

1

0.66667

0.33333

0.66667

0.66667

0

0.66667

1

0.66667

0.66667

0.66667

1

0.66667

0.33333

0.66667

1

0.33333

0.66667

0.66667

0.66667

0

1

DM1

0.66667

0.66667

0.33333

0.33333

0.33333

0.33333

0.66667

0.66667

0

0

0

0.66667

0.66667

0.33333

0.33333

0.66667

1

0.66667

0.66667

0.66667

0

1

DM2

0.66667

1

1

0.66667

0.66667

0.33333

0.66667

1

0.33333

0.66667

0

0.66667

0.33333

0.66667

1

0.66667

0.66667

1

0

0.66667

0

1

DM3

0.66667

1

0.66667

1

1

0.33333

0.66667

1

0.66667

0.66667

0

1

0.33333

0.66667

1

1

1

1

0

0.66667

0

1

DM4

0

1

1

1

1

1

0.66667

1

0.66667

0.66667

0

1

0

0

1

1

0

1

0

1

0

1

DM5

0.66667

1

1

1

0.33333

1

0.66667

0.33333

0

0

0.66667

0.33333

0.66667

0.66667

0

1

0.66667

0.66667

0.66667

0.66667

0

1

DM6

0.33333

0.66667

1

1

1

0.66667

0.33333

1

0.66667

0.66667

0.33333

1

0.33333

0.33333

0.66667

0.66667

0

0.66667

0

0.66667

0

1

DM7

0

1

1

1

1

0.5

1

1

0

0

0

1

0

1

1

0

0

1

0.5

1

0

1

DM8

0

1

1

1

1

0.5

1

1

0

0

0

1

0

0.5

1

0

0

1

0

1

0

1

DM9

0.66667

1

1

0.66667

1

1

1

1

0

0

0.33333

1

0.66667

0.66667

0.66667

1

0.66667

0.66667

0.66667

0.66667

0

1

DM10

0

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

1

1

0.5

0

1

DM11

JGOSS

Cha.

C1

C2

C3

C4

C5

C6

C7

C8

C9

C10

C11

C12

C13

C14

C15

C16

C17

C18

C19

C20

S. N.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Min

Max

DM2

0.333333

0.333333

0.666667

0.666667

0.666667

0.666667

0.333333

0.333333

1

1

1

0.333333

0.333333

0.666667

0.666667

0.333333

0

0.333333

0.333333

0.333333

0

1

DM1

0

0.333333

0.666667

0.333333

0.333333

1

0.333333

0

0.333333

0.333333

0.333333

0

0.333333

0.666667

0.333333

0

0.666667

0.333333

0.333333

0.333333

0

1

0.333333

0

0

0.333333

0.333333

0.666667

0.333333

0

0.666667

0.333333

1

0.333333

0.666667

0.333333

0

0.333333

0.333333

0

1

0.333333

0

1

DM3

0.333333

0

0.333333

0

0

0.666667

0.333333

0

0.333333

0.333333

1

0

0.666667

0.333333

0

0

0

0

1

0.333333

0

1

DM4

1

0

0

0

0

0

0.333333

0

0.333333

0.333333

1

0

1

1

0

0

1

0

1

0

0

1

DM5

0.333333

0

0

0

0.666667

0

0.333333

0.666667

1

1

0.333333

0.666667

0.333333

0.333333

1

0

0.333333

0.333333

0.333333

0.333333

0

1

DM6

0.666667

0.333333

0

0

0

0.333333

0.666667

0

0.333333

0.333333

0.666667

0

0.666667

0.666667

0.333333

0.333333

1

0.333333

1

0.333333

0

1

DM7

1

0

0

0

0

0.5

0

0

1

1

1

0

1

0

0

1

1

0

0.5

0

0

1

DM8

1

0

0

0

0

0.5

0

0

1

1

1

0

1

0.5

0

1

1

0

1

0

0

1

DM9

0.333333

0

0

0.333333

0

0

0

0

1

1

0.666667

0

0.333333

0.333333

0.333333

0

0.333333

0.333333

0.333333

0.333333

0

1

DM10

0

0.333333

0.666667

0.333333

0.333333

1

0.333333

0

0.333333

0.333333

0.333333

0

0.333333

0.666667

0.333333

0

0.666667

0.333333

0.333333

0.333333

0

1

DM11

Supply chain

distribution

during

COVID-19

Table 5.

Deviation sequence

values of decision

matrix (for

challenges)

Cha.

C1

C2

C3

C4

C5

C6

C7

C8

C9

C10

C11

C12

C13

C14

C15

C16

C17

C18

C19

C20

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Table 6.

Grey relation

coefficient of decision

matrix (for

challenges)

S. N.

1

0.6

0.428571

0.6

0.6

0.333333

0.6

1

0.6

0.6

0.6

1

0.6

0.428571

0.6

1

0.428571

0.6

0.6

0.6

DM1

0.6

0.6

0.428571

0.428571

0.428571

0.428571

0.6

0.6

0.333333

0.333333

0.333333

0.6

0.6

0.428571

0.428571

0.6

1

0.6

0.6

0.6

DM2

0.6

1

1

0.6

0.6

0.428571

0.6

1

0.428571

0.6

0.333333

0.6

0.428571

0.6

1

0.6

0.6

1

0.333333

0.6

DM3

0.6

1

0.6

1

1

0.428571

0.6

1

0.6

0.6

0.333333

1

0.428571

0.6

1

1

1

1

0.333333

0.6

DM4

0.333333

1

1

1

1

1

0.6

1

0.6

0.6

0.333333

1

0.333333

0.333333

1

1

0.333333

1

0.333333

1

DM5

0.6

1

1

1

0.428571

1

0.6

0.428571

0.333333

0.333333

0.6

0.428571

0.6

0.6

0.333333

1

0.6

0.6

0.6

0.6

DM6

0.428571

0.6

1

1

1

0.6

0.428571

1

0.6

0.6

0.428571

1

0.428571

0.428571

0.6

0.6

0.333333

0.6

0.333333

0.6

DM7

0.333333

1

1

1

1

0.5

1

1

0.333333

0.333333

0.333333

1

0.333333

1

1

0.333333

0.333333

1

0.5

1

DM8

0.333333

1

1

1

1

0.5

1

1

0.333333

0.333333

0.333333

1

0.333333

0.5

1

0.333333

0.333333

1

0.333333

1

DM9

0.6

1

1

0.6

1

1

1

1

0.333333

0.333333

0.428571

1

0.6

0.6

0.6

1

0.6

0.6

0.6

0.6

DM10

0.333333

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.333333

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

1

1

0.5

DM11

JGOSS

S.N.

Challenges

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

C1

C2

C3

C4

C5

C6

C7

C8

C9

C10

C11

C12

C13

C14

C15

C16

C17

C18

C19

C20

GRG

Rank

0.523810

0.845455

0.814286

0.793506

0.777922

0.595671

0.684416

0.866234

0.454113

0.469697

0.414286

0.829870

0.471429

0.547186

0.732900

0.724242

0.551082

0.818182

0.506061

0.700000

15

2

5

6

7

12

11

1

19

18

20

3

17

14

8

9

13

4

16

10

Note: GRG = Grey Relation Grades

Supply chain

distribution

during

COVID-19

Table 7.

The summary of

grey relation grades

and ranking (for

challenges)

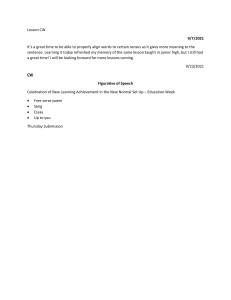

process during the impact of the COVID-19 is shown in Figure 2. The final rank of key

supply chain challenges is C8 > C2 > C12 > C18 > C3 > C4 > C5 > C15 > C16 > C20 >

C7 > C6 > C17 > C14 > C1 > C19 > C13 > C10 > C9 > C11. Table 7 shows “Impact of

political factor” (C8), “Delay in import process” (C2), “Weak internet connection” (C12) while

“Weak knowledge of the use of digital platform” (C10), “Poor information sharing in online

by employees” (C9), “Information flow from top management to operational level” (C11)

have been identified as top and bottom three key challenges, respectively. Afterward, the

positions of other challenges are measured in-between two ends. Moreover, it helps to

improve the supply chain distribution level and good planning to overcome the COVID-19

pandemic with appropriate decision-making.

Table 8 represents the scores of the decision matrix for the individual key supply chain

opportunities. In the similar way, we have followed various GRA steps (Steps 1, 2, 3 and 4)

as above have been followed and analyzed to measure the rank of these managing the

Histogram

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

GRG

C1

C2

C3

C4

C5

C6

C7

C8

C9

C10

C11

C12

C13

C14

C15

C16

C17

C18

C19

C20

Figure 2.

Ranking of the key

supply chain

challenges

JGOSS

Table 8.

The scores of the

decision matrix (for

managing the

opportunities)

S. N.

Opportunities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Min

Max

MO1

MO2

MO3

MO4

MO5

MO6

MO7

MO8

MO9

MO10

MO11

MO12

MO13

MO14

MO15

MO16

MO17

MO18

MO19

MO20

DM1

DM2

DM3

DM4

DM5

DM6

DM7

DM8

DM9

DM10

DM11

2

4

4

4

4

4

4

3

4

4

4

4

5

5

4

3

3

4

5

4

2

5

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

3

4

4

3

4

4

3

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

5

4

4

3

3

4

4

3

5

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

3

4

4

3

4

4

4

4

4

5

5

2

4

4

4

5

5

4

4

5

4

3

3

4

5

2

5

5

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

5

4

4

4

5

4

4

4

3

5

4

4

4

4

4

5

4

5

4

4

5

3

3

4

4

3

5

5

3

3

5

5

5

5

5

5

3

4

3

5

3

3

5

2

2

4

3

2

5

5

3

3

5

5

5

5

5

5

4

3

4

3

5

3

5

2

2

4

3

2

5

4

3

3

2

3

3

3

4

3

4

4

4

5

5

3

5

4

4

3

4

2

5

5

5

4

5

5

5

4

4

3

4

4

4

3

4

3

3

4

4

4

5

3

5

opportunities, presented in Tables 9, 10, 11 and 12, respectively. The highest the grade the

best will be the choice, so accordingly, on the basis of this calculated grey relational grade,

the ranking of these opportunities that need to manage the supply chain process during the

impact of the COVID-19 is shown in Figure 3. The final rank of key supply chain challenges

is MO5 > MO1 > MO6 > MO14 > MO16 > MO13 > MO4 > MO11> MO8 > MO20 >

MO9 > MO7 > MO12 > MO19 > MO2 > MO10 > MO3 > MO15 > MO17 > MO18.

Table 12 shows the “Inventory management” (MO5), “Selection of transport method” (MO1),

“Operational cost” (MO6) and “Marketing and brand Innovation” (MO15), “Online delivery

of products” (MO17), “E-commerce enablement (launching applications, tracking system)”

(MO18) are identified as the top and bottom three managing the opportunities, respectively.

Afterward, the final rank of other opportunities is measured in between two ends.

5. Discussion and findings

This work explicitly indicates the challenges and how to manage the opportunities to

mitigate the challenges through uncertainties, real-time information and agility in the digital

supply chain of Pharmaceutical distribution companies in Myanmar. Research results

reveal that COVID-19 and political conflict immensely surge and impact the pharmaceutical

enterprise in Myanmar. There are 20 challenges and 20 factors of managing opportunities.

The factors used in the study are extracted from the existing literature by the fact that

current affairs, geographical conditions, industrial infrastructure and secondary data of the

company profile emphasize a particular business context in a particular country.

Participants are asked to answer these factors with five-point Likert scales. Next, the GRA

method is applied to analyze the data, and the results rank the most and the least critical

factors for both challenges and countermeasures of the opportunities.

DM1

0

0.66667

0.66667

0.66667

0.66667

0.66667

0.66667

0.33333

0.66667

0.66667

0.66667

0.66667

1

1

0.66667

0.33333

0.33333

0.66667

1

0.66667

0

1

Opp.

MO1

MO2

MO3

MO4

MO5

MO6

MO7

MO8

MO9

MO10

MO11

MO12

MO13

MO14

MO15

MO16

MO17

MO18

MO19

MO20

S. N.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Min

Max

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

0

1

1

0

1

1

0

1

DM2

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

1

0.5

0.5

0

0

0.5

0.5

0

1

DM3

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

0

1

1

0

1

DM4

0.66667

0.66667

0.66667

0.66667

1

1

0

0.66667

0.66667

0.66667

1

1

0.66667

0.66667

1

0.66667

0.33333

0.33333

0.66667

1

0

1

DM5

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

1

DM6

0.5

0.5

0.5

0

1

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

1

0.5

1

0.5

0.5

1

0

0

0.5

0.5

0

1

DM7

1

0.33333

0.33333

1

1

1

1

1

1

0.33333

0.66667

0.33333

1

0.33333

0.33333

1

0

0

0.66667

0.33333

0

1

DM8

1

0.33333

0.33333

1

1

1

1

1

1

0.66667

0.33333

0.66667

0.33333

1

0.33333

1

0

0

0.66667

0.33333

0

1

DM9

0.66667

0.33333

0.33333

0

0.33333

0.33333

0.33333

0.66667

0.33333

0.66667

0.66667

0.66667

1

1

0.33333

1

0.66667

0.66667

0.33333

0.66667

0

1

DM10

1

1

0.5

1

1

1

0.5

0.5

0

0.5

0.5

0.5

0

0.5

0

0

0.5

0.5

0.5

1

0

1

DM11

Supply chain

distribution

during

COVID-19

Table 9.

Normalized values of

decision matrix (for

managing the

opportunities)

JGOSS

This thesis has identified 20 critical factors of challenges during a pandemic. The impact of

political factors (C8) is indicated as the most crucial aspect being faced in the digital supply

chain of Myanmar’s pharmaceutical company. Political instability increases uncertainties

related to all areas of supply chain activities such as inventory management, transportation,

high cost and operations. Fear of security collapse forces the people to purchase the

excessive number of products that causes the higher demand. A sudden high level of

demand brings the shortage of raw materials together. To meet the higher demand, the

manufacturing company attempts a higher production rate. However, both pandemic

restrictions, e.g. lockdown and several constraints caused by political issues interrupt the

transportation and delay in import process (C2) which is standing at the second-ranked

place in this study. Delay in import process is a severe problem for the case pharmaceutical

distribution company because its product merchandising is mostly from ASIAN countries

such as Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand which also suffer an operational interruption of

COVID-19 outbreak. In addition, another strictly constrained factor is a weak internet

connection (C12) because the internet is the key in the digital supply chain during the

pandemic. On the other hand, weak knowledge of the use of the digital platform (C10) is

ranked as the third least crucial factor followed by poor information sharing online by

employees (C9) as the second least important factor and information flow from top

management to operational level (C11) as the least vital factor. Therefore, this study affirms

some factors belonging to real-time information do not impact significantly on digital

supply chain during the pandemic.

During the pandemic, managing the opportunities is the key performance to mitigating

the risks and challenges within and across the digital supply chain. After investigating 20

factors, inventory management (MO5) is listed as the most critical factor. Panic buying

caused by pandemic and political instability directly and significantly impacts inventory

control. Logistics restrictions due to COVID-19 spread also have negative effects on

inventory management. To overcome it, selection of the transport method (MO1) plays the

second most pivotal aspect to operate at low cost with good quality. Since pricing becomes a

matter, reducing the waste of operational cost (MO6) resides at the core of operation

management as the third most important element. Surprisingly, marketing and brand

innovation (MO15), which is always a paramount thing in normal circumstances, is the third

least important component during pandemic followed by online delivery of the product

(MO17) and E-commerce enablement (MO19), second least and first least items. It shows that

e-commerce adaption and online delivery are not significantly important in managing

opportunities for the pharmaceutical company of Myanmar, wherein internet access is one

of the most challenging aspects.

Histogram

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

Figure 3.

Ranking of managing

the supply chain

opportunities

0

GRG

O1

O2

O3

O4

O5

O6

O7

O8

O9

O10

O11

O12

O13

O14

O15

O16

O17

O18

O19

O20

DM1

1

0.333333

0.333333

0.333333

0.333333

0.333333

0.333333

0.666667

0.333333

0.333333

0.333333

0.333333

0

0

0.333333

0.666667

0.666667