a concise history of

western

architecture

R.

FURNEAUX JORDAN

UOM^

\<jJiLu^

A CONCISE HISTORY OF

WESTERN ARCHITECTURE

R.

FURNEAUX JORDAN

A CONCISE HISTORY OF

WESTERN

ARCHITECTURE

\m

HARCOURT, BRACE JOVANOVICH, INC

To E.M.FJ.

(Q 1969 BY THAMES AND HUDSON LIMITED

All

rights reserved.

No part of this publication

may

LONDON

be reproduced,

or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any information storage

retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the publisher.

*

Reprinted ig84

Library of Congress Catalog

Printed and

and

bound

in

Card Number: jg^ggsSS

Spain by

Artes Graficas Toledo S.P.A.

D.L. TO-291 84

CONTENTS

6

Preface

7

CHAPTER ONE

Introductory

23

CHAPTER TWO

Classical Greece

45

CHAPTER THREE

The Roman Empire

71

CHAPTER FOUR

The Byzantine Empire

95

CHAPTER FIVE

Western Christendom

125

CHAPTER

SIX

Western Christendom

167

Romanesque

I:

II

:

Gothic

CHAPTER SEVEN

Renaissance, Mannerism, and Baroque in Italy

213

CHAPTER EIGHT

Renaissance, Mannerism, and Baroque outside Italy

259

CHAPTER NINE

The Return to Classicism

283

CHAPTER TEN

The Nineteenth Century

307

CHAPTER ELEVEN

The Modern Movement

338

A Short Bibliography

340

List of Illustrations

355

Index

"t

PREFACE

This book

main

at the

dawn

an attempt, in a very small compass,

is

Western architecture from the

trends of

of history to the present day. Even more,

show how

attempt to

look

to

it

and forms of

the actual structure

architecture were almost always the product of time

space - of circumstance more than

-

and actions

Man's thoughts

his religion, politics, art,

technology and

the things from

which an

architecture

a civilization, rightly interpreted,

tion of the society

man and

little

to the

thing he

is

to

an

art

tied

either in

more marked than

the painter, poet,

in

This

to

some

without

It

is

some

artist,

at least also

by

special twist or

may design it a

man; what he can

own

era.

limits, this dialectical

any other

sort

He

purposes and executed

art.

To some

own

law

extent

in^

generation -

of ivory tower; the architect

the product of a

would be an

of

an iron law

composer, sculptor - although

never. Architecture

stances.

is

True, the

evitably a child of his time serving his

can withdraw

art

time or space. In architect

practical

to

The

are

designing, and

always within severe practical

is

give

born.

produce something not of his

cannot be elsewhere

ture,

is

may

worse than the next

better or

never do

it.

all his artefacts.

skill

is

and climate

a very precise reflect

is

which produced

reason of his taste or

charm

and

will.

aspirations, as well as landscape, geology

concerning

an

is

hundred circum/-

arid task to study the architecture

glancing

at the

circumstances.

R.F.J.

Chapter One

INTRODUCTORY

All European

culture, not least

beginnings outside Europe. Prehistoric

much

widely over

thin

on

its

man had spread

He was

of the habitable world.

ground but he was

the

had

architecture,

its

many thousands of years

there.

And

through

yet,

- whether hunter, shepherd

or

fisherman - he had never organized himself into any kind

of community larger than the family or the group of

families

we call a tribe. His energy was concentrated upon

survival in a hard world, following his flocks from

pasture to pasture, picking berries as he went.

marvellous uninhibited talent of a child

of a savage

his cave, the resourcefulness

his hut.

baskets,

He

many

invented

pots,

things

-

canoes - but, never

He had the

when

when

painting

building

spears, fish-hooks,

settling,

he never

invented the town.

Only when man could

to

'civilization',

and

therefore architecture,

This liberation was the

It

came,

deltas,

this

where the

upon

a

first

map we

comes into existence

was black and

reeds. If

from

tion spreads outwards

at

the valleys of the Tigris

we

plot the

and

in their

fertile,

first

and

civiliza^

shall find, not that civiliza^

a centre, but rather that

more than one

are several tiny caterpillars

like

revolution in the story of man.

alluvial soil

world

thraldom

come into being.

to start with, in the great river valleys

one could build with

tions

himself from

economy could anything

hunter/fisher

the

free

point, that there

of culture upon the globe

and Euphrates

it

in

.

.

.

Mesopotamia,

of the Nile in Egypt, of the Indus in north^'west India

and of the Yangtse

in

China. They

all

had one thing

in

INTRODUCTORY

Common,

Each of these

a mastery of irrigation.

valleys

most of all the Nile - when the annual snows melted

the

in

mountains hundreds of miles away, was flooded. The

silt^bearing water crept inch by inch over the level fields

depositmg

When man

precious load.

its

control this flood, with dykes, ditches

then his corn seed was returned to

fold.

It

and

was

many were

the

even leave the

It is

man

possible for one

upon mind,

and

sold.

and

far

that ideas

So

in

Upper Egypt,

mind can sharpen

came

the city there

came

first

in the Delta

and then

mathematicians,

prostitutes

scribes, doctors,

and

and

astronomers and

merchants,

actors,

was

architects. It

in

And with

also into history not only priests

and

and

Mesopotamia

into history the city.

kings, but lawyers

potters, artists

itself

and techniques can be exchanged

China),

there

many,

in cities.

in the Nile Valley (as also in

away

for

They might

freed for other tasks.

especially in cities that

to

hundred^

several

grow corn

to

how

and water-wheels,

him

and come together

soil

learnt

the beginning of all

things.

As

sixteenth^'Century

Spain and England accepted the

challenge of the sea and of a

Rome

New

World,

as

ancient

accepted the challenge of a continent and built

an empire, so Egypt accepted the challenge of reeds and

swamps and

nation.

hot sand and flood, and built the

Other people came

similar ways, but

first

into existence in not dis^

Egypt was unique.

To

Nile

live in the

Valley was to be enclosed, from birth to death, within a

geography and a routine of extraordinary simplicity.

There were few things

Egyptian mind; such

impress themselves

to

psychological impact was

Itself

- source of

regularity of sun,

the grave.

It

all

they were,

as

terrific.

moon and

was out of

things that the Egyptians

however,

the

stars; there

was

the fear

made

the

their

There was the Nile

was

there

life;

upon

mysterious

fertility

and mystery of

their

and

these

complex hierarchy

of gods, and their strange reHgion. In the service of that

8

religion they

made

their art

and

their architecture.

Egyptian theology, with

its

The

animal/'headed gods, was complicated.

strange

most important thing was the belief that survival

death depended

upon

Immortality was only for privileged royal and

might hope

world beyond the

in the

to

after

body.

the preservation o{ the

beings, except that a servant

INTRODUCTORY

pharaohs and

deified

priestly

be a servant

servitude to his

stars, in eternal

At the day of resurrection the spirit or Ka of the

dead man would enter once more into his body; the body

master.

must be

moment. In

there, intact, ready for that

historic times the fact that the dry desert

to preserve the

came

skill,

world's

corpse

sand had helped

the idea of what

be called 'the good burial'. For three thousand

to

years that idea

high

body may have suggested

pre-'

first

was an obsession. Embalming became

one of the most important sciences in the

civilization.

was embalmed

or

followed logically, once the

It

mummified,

that

preserved in an impregnable tomb.

difficult.

a

The

impregnability of the

problem, and indeed the

Impregnabihty had

to

basis,

it

must

also be

This was more

tomb became

the

of Egyptian architecture.

be provided in more than one

form, security for the cadaver, and security for the dead

man's possessions his jewels.

his wives, his furniture, his

The accumulated

Egypt, with which the world's

objets

d'art

museums

food and

Ancient

of

are filled,

once in tombs, awaiting a second existence

were

at

the

resurrection. The tomb was not only an impregnable

monument;

it

was

a storehouse, a chapel

and

a

work of

art.

The Egyptian tomb had

to

to

be not only durable,

it

had

look durable. Apart from prehistoric graves - which,

1

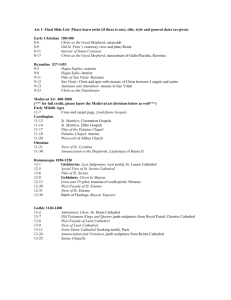

Reconstruction of the tomh^complex

of Zoser

at

showin£^ the Step

by ritual buildings,

entrails

-

jars for food,

ointment and

tombs were

the mastahas of

the earliest historic

%:\7\:^^

BC),

Pyramid surrounded

all

within a stone-'

faced wall: (a) entrance; (b) hall of

pillars;

(c)

ceremonial

court;

(d)

storeAiouses ; (e) double^throne and (f)

shrines of Upper and Lower Egypt; (g)

and (h) south and north buildings and

courts, possibly

stration of

however, already contained

Saqqara (c.2680

symbolizing the admini^

Upper and Lower Egypt;

mortuary temple; (j) south tomb.

Pharaoh's tomb

lies

(i)

The

under the pyramid

the I-III Dynasties of the

Archaic Period

(c. 3

B c). They were mainly near Memphis, a

tombs were small with stepped

name coming from

top (their

little

south of

Old Memphite Nome. These

Cairo, capital of the

mastaha

200-c. 2700

the

and

sides

Arabic

a

flat

bench

for a

of the type found outside the doors of Arab houses). They

were almost solid but somewhere in the heart of the mass

of mud^brick or masonry was a

series

chamber containing

the burial

dead, with

2

Saqqara.

Columns

ridded stem

III.

-

in

the shape

tulips shaped flowers

in

of

and

this false

offerings could be

of the soul.

mastaha

was faced with limestone blocks brought

from the mountains bordering the Nile Valley. These

were

and accurately cut

finely

for their

place in the

the north court (h, in

i); the builders did not yet trust

stone enough to

a

dead, and where the priest could say prayers

for the repose

papyrus - with

was

body. This recess

to the

where

also served as a small chapel

The

there

blocked^up door. Through

door the Ka or soul could return

to the

the sarcophagus of the

impedimenta. Externally

all his

recess simulating a

made

ofrooms, including

make them free-standing.

Symbolic of Lower E^ypt,

the

papyrus

became a common decorative motif

sloping walls. Functionally, therefore, the mastaha was

designed to achieve permanence. Aesthetically

designed

it

involved metal tools, mathematics, trans^

and organized labour.

port

was

look permanent in an impressive way.

to

Technically

it

apparent simplicity -

It

was, in

architecture. It

was

a great development.

It

pyramids, while the

little

was

fact

for all

also the

clearly the

recess or

-

its

germ of

embryo of

chapel was

the

be

to

developed eventually, in Upper Egypt, into the great

mortuary temples of Thebes on the west bank of the Nile

Luxor. The

at

fine stone^cutting

of a masonry tradition which was

start

golden thread through

The

first

scale

10

It

Known as the

was

the

to

run Hke a

the architecture of Europe.

Memphis and

development of the

in form.

high;

all

'pyramid' was buik as early

Sakkara, between

III

of the mastaha was the

as

the Nile.

f.2680 bc, at

It

was

a larger

mastaha^ not truly pyramidical

Step Pyramid,

tomb of

the

it is

some 200

^ttt

Pharaoh Zoser of the

Dynasty, and formed part of a large and very

sophisticated

group of buildings. Most of

these are in

sham - simply

effect

mere

the

on

A

solid rubble cores

of stone

fact that they are

importance.

over

facades

of tremendous

is

double throne symbolized Zoser's rule

Upper and Lower Egypt, and

in a small sealed

all,

number of features

a

two kingdoms. At

exist in duplicate to represent the

the heart of

- but

chamber next

to the

pyramid, was the grim seated statue of Zoser, once

with malachite eyes

A

and

Pyramid

once a

itself

Museum).

in the Cairo

come

maturity.

to

Layout,

setting, as well as painting and sculp"

become

have

ture,

now

is

has here

civilization

plan, vista

(this

part

The

of architecture.

has long since

lost its facing,

giant's

to

clear-cut

staircase

Step

but was

The

Heaven.

whole group was contrived, considered, designed.

know

the

name of

His technical

the architect.

was

skill

imagination that was

but

great,

now

He was

was

it

Imhotep.

the creative

recognized for the

time as a divine attribute of man. Imhotep was

a

High

honour

later

Priest

of

Re

the

in this world,

ages he

Sun God, and was

and of immortality

was revered

as a sage

and

We

first

made

assured of

in the next. In

as the

patron god

j,

4

Giza. Below,

Cheops

Chephren

A

little

right.

the

north of Memphis, on the rocky plateau

Mykerinus;

and

Above,

now

the

pyramids of many

courtiers, austere

sizes,

mastaba

tombs

basalt,

free-standing

of

and unadorned funerary temples cut

with beautiful precision, underground passages and,

almost always, wherever one might be, the sharp apex of

a

pyramid against the blue sky

their

or the stars. There, with

golden furniture, jewels and spices around them,

kings and queens, princes and princesses, were buried.

There, during the

IV Dynasty, the three largest pyramidal

tombs were

by three pharaohs, Cheops, Chephren

built

and Mykerinus: each pyramid was

life

and of eternal servitude

The

largest (c.2575

a

symbol of eternal

to the king.

Bc) was buik by Cheops.

It

was

<!^

^nr

in every sense a climax, historically

and

aesthetically.

masonry

IV Dynasty:

rows o{

for the burial

mortuary temple by

Its severe

of the

of Giza, was the royal cemetery - an orderly arrangement

of windless courts paved with green

mastaba

Nile where Chephren's body was

teristic

to the

pyramids of

foreground),

tombs, for the courtiers, are visible at the

embalmed.

of medicine.

the

BC,

(c.2^'/^

is

charac^

the piers are

INTRODUCTORY

Although Imhotep's work at Sakkara was a brilliant

revolution - virtually the creation of architecture as an

art

-

was only one of a

it

Dashur, leading

to the apotheosis

Pyramid contained

stone.

lost.

It

was 480

Each

series

of Giza. This Great

and a quarter million tons of

six

feet

- Sakkara, Medum,

high before the apex stones were

side of the square base

mathematical error of about

003

was 760

per cent.

pyramid of Mykerinus

Giza

conjectural

Four

(a

at

reconstruction).

rubble ramps were built, pro^res-^

sively higher, around the stone casing of

the pyramid.

men dragged

Nile,

on

Up

in place,

the

removed and

the side

-

joints

of an inch - jeweller's

onez-fiftieth

work unexcelled by

the builders of the Parthenon.

impressive were the actual mechanics of

men worked

The blocks of

construction. Herodotus says that 100,000

for

twenty years fed on a diet of onions.

stone,

some of them 20

feet

from the quarry by barge

by 6

feet,

would be brought

height of the Nile flood,

at the

three

stone,

sledges;

crews descended.

of these teams of

brought from the

The

between them were

Almost more

the

with a

Each polished

block weighed about two and a half tons.

5 Building

feet,

by

Once

the fourth

the

the capstone

was

ramps would

and then dragged up

hundred

feet

ramp

a

above the

both ends of the journey

at

river.

to the

Wedges,

Pyramid

site,

a

rockers, levers,

be gradually

the stone facing

polished

but they had to be handled

-

visible at

cradles

and

sledges were

was the wheel - no

carts,

all

no

used.

The

pulleys,

missing element

no cranes.

The Great Pyramid

mystical

is

a valid

symbol of a

The

culture.

meaning of the measurements and proportions

unknown;

it

mathematics not

is

certain,

as a

mystique, an end in

Greek

this

is

mere

itself

attitude to

however, that here

we have

tool of the engineer, but as a

God

is

a mathematician.

mathematics

as art that

It is

would seem

6

Instead of pyramids,

have come into the world with the tomb o{ Cheops.

The pyramids mark the culmination o{ the Old

Kingdom - monolithic, immutable, austere, puritanical.

There followed an interregnum and a 'dark

VII

to

X

age'

pharaohs

mortuary temples at Thebes Such

was

the

.

(XIX

Ramesseum

oj

'Kameses II

Dynasty), seen here from

the

court looking towards the pillared hall

The

court

was decorated with

colossal statues of the

Osiris (see also

to

later

built

pillars

III.

reliejs

pharaoh as

ij).

the

The

anc

god

squat

beyond have both papyrus and

lotus^bud capitals

- the

Then once more, about 2000 bc,

history. With the rise of the Middle

Dynasties.

Egypt emerges into

Kingdom

pharaohs a new capital was established

at

Thebes, 300 miles south of Memphis. In 1370 bc,

Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten) was to

at Amarna (now Tel-'el^Amarna)

build a

to

the

Thebes, but the Theban area remained in

metropolitan province of Egypt until

the

Roman Empire two

enter

upon

thousand

its

city

north

effect

of

the

absorption in

years later.

the age of the great temples.

new

We

now

13

INTRODUCTORY

This development in the

no corresponding change

burial', the preservation

was

for use in the next,

is,

of architecture

use

in

life

The 'good

or religion.

of the material things of this

still

pyramid had been

bility, so far

a failure. Their massive impregna-'

and

sacrilege

Nevertheless the dead must

and

must

there

and

sacrificial offerings

now

The fact

tomb and

from protecting the tomb, had advertised

existence. Pilfering

possessions,

life

the basis of all belief

however, that functionally both the mastaha

the

signifies

The

be hidden.

in the mastaha wall,

still

still

had been rampant.

be buried with

all their

be a sacred place for

tomb must

prayers. In short the

mere

offering niche, once a

recess

had already become a considerable,

but nevertheless subordinate, chapel of the pyramid.

now assumed overwhelming

tombs of the

hills.

to

deified

Here and

give the

(i.e.

importance.

mortuary temples) related

to the

pharaohs buried deep in the Theban

Deir el^Bahari, the temptation

mountain tomb some

-

irresistible.

On

great architectural

combine tomb and temple - was

to

still

A number of

really

there, as at

frontispiece

the whole, however, the

worked. The temples, on a

new

tombs.

Some may

tomb of

amassed

the

boy

are

king,

was

treasures,

There

be there

many

all

deep

known,

the

Tutankh^Amun, with

its

still.

well

is

substantially intact until 1922.

Karnak

originally

compound, with

their

beautiful single temples throughout

the Nile Valley, but at

of temples,

As

system

were built near the

vast scale,

while the dead kings were sealed in

river,

It

Theban Empire were

the great temples of the

funerary chapels

its

there

a

is

whole complex

contained within a sacred

a sacred lake bearing a

The compound was approached from

colony of ibis.

the Nile by

an

avenue of carved couchant rams. These temples were

built

There

is

unless

we

to

14

through the centuries by a whole

Rome,

series

of pharaohs.

nothing comparable in the Western world

think of each

Roman

emperor adding a forum

or the cathedrals being

four or five centuries.

The main

added

to

through some

core around

which

the

^

1

Jll

e

If

11

If

fl

II

jl

o a

i>anirWiaMic

rest

grew was

the great

^

iiiuiia>-,<iaiiiug

Temple of Amun, begun

in the

XII Dynasty (1991-1786 bc). Other pharaohs added

7

Temple of Amun

Precincts of the

^kdmak (XI J Dynasty

Approaching from

temples, pylons or temple courts until the end of Egypt's

history.

The dead

other gods,

was

but deified pharaoh, absorbed into the

would be worshipped. His

interest, therefore,

of rams

avenue

The

which

that

of

Amun

was

merely a large version, had usually an outer court open

to the sky

but with columns round, as in a cloister; then,

that,

a large

columned

hall followed

by the

sanctuary; then beyond that again a rabbit-warren of

rooms where the priests lived and planned

The

central

room of this

the holy of holies

temple rooms

lit

-

if at all

all

- by

small hole in the

inner

where the

their

complex was

cult statue

was

ceremony.

Nile

the

one

(a),

by

the

enters

the

Tuthmosis

III

kept.

The

8~ioJ

festival hall of

The

(d).

length

is

(I-VI), added by

successive pharaohs. Further pylons on

VII-X)

lead towards the

Temple of Mut, standing

in a

separate

enclosure like that of Monthu (e).

to the

Temple of

Amun

III (g).

The

Next

are the sacred

lake (f) and a temple added by

the shrine,

at

after).

see also Ills.

to the

interrupted by pylons

another axis (

beyond

(c,

past the sanctuary

typical temple, of

and

Temple of Amun proper, which stretches

from the great courtyard (b) through the

hypostyle hall

personal.

f

Rameses

precincts are completely

walled

looked inwards upon courts, and were

a small shaft of sunlight penetrating a

flat

stone roof

The

enclosing wall (the

15

INTRODUCTORY

had no windows; moreover

temenos) therefore

it

was

double so that the whole temple was surrounded by

All the columns,

totally inaccessible security corridor.

the walls,

all

were completely covered with incised

and hieroglyphs - hymns

pictures

a

to the deities

and

statements of self/glorification by the pharaohs.

The avenue of rams - which began

8-10 Hypostyle

Dynasty).

hall,

Below,

and

plan

section

looking alon^ the main axis: the more

massive central columns, with papyrus

capitals,

clerestory

support

lighting

lower pillars

(compare

at

have

111. 6,

roof with

higher

a

the

sides.

lotus^hud

of the

same

The

capitals

showing

stone grilles.

treatment

the

One

clerestory

sees

the

-

were

all

with

As

planned with

Egyptian

of masonry - columns and

symmetry, on a single

so often throughout history

in the

The

grand manner -

central

doorways,

hall

axis.

- whenever planning

the real basis ot

for instance,

most curiously cut away so

were the pylons. These

prominent

feature of every

they are 140

hieroglyphs, so delicate that they do not

feet

it is

the procession.

have

that banners

is

their lintels

and standards

pairs of pylons are the

most

times

become

At Karnak

pennons, and bearing in very low

accounts of the glory of pharaoh, about

relief epic

eight

Egyptian temple.

high - near/solid masses of masonry,

slotted for masts flying

covered with slightly incised figures and

mass

strict

columned

the

its

walls of tremendous weight and mass

detract from the junctional

and

the entrance, the court,

landings

could pass through unlowered. Flanking each doorway

date).

Opposite, a view across the hall along

a-a,

stage

(XIX

Karnak

at the

life

size.

Symmetry and grandeur have

part of architecture.

We are led by this symmetry and grandeur all the way

from the avenue of rams into the outer court, and from

the court into the hypostyle hall. This hall

significance.

columns

It

is

a

are very massive,

single slabs can bridge

vistas

columned

and

and

hall.

The

is

of great

cylindrical

are closely spaced so that

from one column

to another.

The

the glimpses from one side of the hall to the

LOt^^

INTRODUCTORY

and dramatic. The

Other are mysterious

by 160

feet.

each 69

Down the centre

feet

is

hall

is

320

feet

an avenue of 12 columns,

high and nearly 12

feet in

diameter. These

On

have bell^shaped capitals based on the lotus blossom.

of

either side

are other

columned

high and 9

avenue or 'nave' of columns,

this central

each with 60 columns, 42

areas,

diameter. Since the central avenue has

feet in

columns higher than those of the

roof of the central area

of the side

halls.

some 20

is

area

feet

on

either side, the

higher than the roof

This means that there

between the higher and the lower

roof,

is

a vertical wall

and

These admit daylight into the

of lighting - where one

than another part -

an

light

effective

grilles.

high up. This method

part of a building rises higher

called 'clerestory lighting'.

is

found again and again

nave of a cathedral

hall

can

that this

be pierced by windows - actually by large stone

is

feet

It

is

in history, as for instance in the

when

method.

It

high up, above the

it

above the

rises

aisles.

It

keeps the source and glare of

eye,

and

yet lights brilliantly the

central area of a large building. In the case of the hypostyle

hall at

Karnak

shafts

of

forest

it

must have been

sunlight

brilliant

particularly dramatic

penetrating

of columns. Here and there the

the richly painted hieroglyphics

added

light,

to the history

shadowy

would

catch

and carvings, while

the

would be

in almost complete

colour and

drama have here been

outer parts of the hall

shadow. Mystery,

light

the

-

of architecture.

The simple geometrical forms of Egyptian architecture,

clean and clearz-cut, unadorned except for

reliefs

and

incised hieroglyphs, bore a perfect relationship to the

landscape.

They were

the level desert.

in the

in contrast to the peerless sky

and

They were an echo of the rock formations

mountains beyond the Valley. This,

in early days,

may have been chance. By the time of the XVIII Dynasty

(1570-13 14 Bc)

there

is

little

doubt but

that

the

Egyptians had become conscious, aesthetically conscious,

of the relationship of architecture

18

lies

to landscape.

The proof

in the temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el^Bahari.

MT

mrrai

>^rr:r

12

The

temples of

(XIX

larger

Rameses

II at

Dynasty), before

higher ground.

two

of the

its

Simbel

removal

consisted of four seated statues of the

The

temple,

hollowed out of the rock, was entered

between the two pairs of figures

platforms were fronted by colonnades, on the

back wall of which

are incised

and painted

reliefs telling

to

The stupendous facade

pharaoh, each 6^ feet hi^h.

The

rock^cut

Ahu

of the Queen's divine birth, her expeditions and archie

tectural achievements.

a

From

the upper platform there

wide view of the Nile, but Deir el^Bahari can

is

also be

approached by a mountain path from the Valley of the

Kings where the Queen

The main

deliberate

herself was buried.

point about Deir el/Bahari, however,

simplicity

of

its

architecture,

subordination to the dramatic landscape.

its

reads'

from

pattern of light

far off.

and shade

the

complete

A few strong

horizontal lines contrast with the verticality of the

The broad

is

in the

cliff.

colonnades

Richness, ornament and sculpture are

almost wholly omitted since they could never compete

with the surroundings.

ture in landscape

20

Egypt passed on

An

understanding of

must be added

to

Europe.

architec/-

to those things

which

of the mountain was

If the temple at the foot

INTRODUCTORY

to be part

of the landscape, two courses were open to the builder.

The

first,

as at

Deir

was

el^'Bahari,

would hold

strong lines, such as

to design

with a few

own

against the

their

overwhelming precipice above them, and

The

sculptural ornament.

sculptural architecture

was

other course

on such

avoid

to

to

produce a

a grandiose scale that

would hold

its

own. This seemingly impossible

was undertaken

at

Abu

too,

Abu

Simbel were

it,

task

Simbel on the Upper Nile by

carving the actual face of the mountain.

at

all

built in the

The two

XIX

temples

Dynasty by

ij Just

Simbel

Rameses

about 1250 BC.

II,

The

certainly stupendous, holding

the

mountain

side,

but also

its

when

larger

own

of the two was

not only against

seen from far off across

the river.

A forecourt led to a great facade,

and 100

feet

beyond

sanctuary -

was

It

out of the living rock.

facade one passed into a vestibule with eight

columns representing

Osiris;

wide

was carved with four

Rameses, each 65 feet high -

made possible only by cutting them

this

feet

high. This facade

colossal seated statues ot

Beyond

119

that

the

was

King

a

in the likeness of the

columned

hall

and then

a complete temple underneath a

really the application

god

the

mountain.

of the technique of tomb

building to the making of a temple. (The formation of a

modern

blocks,

level

reservoir has involved cutting out the temple in

and removing

it,

to

be reconstructed

above the water.)

Egyptian building perfectly mirrors

it

was

free

extraneous influences such as an alien culture.

see

it,

however,

it is

misleading.

It

More

creators.

its

than any architecture there has ever been,

all

higher

at a

from

As we

appears to us as

if

it

were wholly an architecture of death. The palaces and

the houses have all vanished centuries ago.

All we

know

of them must be deduced from the paintings and the

contents of the tombs.

The

house, an

affair

of reeds, hanging mats and

wooden columns, must have had a certain airy elegance.

The gardens were formal. The jewel boxes, the bracelets

living

inside the large temple at

(III.

rock

Osiris, the

12), statues cut

represent

Abu

from

Rameses 11

god of the dead

the

as

14 Model of an Egyptian house, from

the

tomh ofMeket^re at Thebes (c.2000

BC).

A

deep,

shady

portico

with

painted papyrus columns looks out on a

small walled garden where

round a pool: as

in

all

trees

sur^

hot climates,

water and shade were highly prized

of lapis lazuli, turquoise and gold, the stone vases, the

gazelles

and dogs

gaming,

the

these

pink alabaster, the golden discs

carved

flamingoes on

beds, chairs

in

and

barges

artificial

for

sailing

among

for

the

lakes, the fragments of lovely

stools, the use

of quartz and faience -

all

things were of an elegance appropriate to the

dappled sunlight of verandahs, shadowy rooms and the

tinkle of fountains

If in

style,

- the

structure

specific contribution to

it

laid the

architecture of an aristocracy.

and ornament Egypt's

direct or

any European style was negligible,

foundation of an attitude

was durable.

22

first

to architecture

which

Chapter Two

CLASSICAL GREECE

The

and influence of Classical Greece became

culture

the basis of a

territories

whole Hellenic world.

It is

found

in the

invaded by Alexander the Great, throughout

Magna Graecia and ultimately in the Roman Empire.

The great Classical Age, however, consisting virtually

of the two generations of Athenian history dominated by

Pericles in the fifth century

perihelion of a comet

a

thousand archaic

-

b c, has been likened

to the

a long, slow preparation through

years, a short blaze

of achievement,

then the long, slow decline.

The

of modern

story

Greek

enters

first

began centuries

Age

was

that

we

upon

earlier,

begins for us

when

but

is

it

not until the Periclean

and the

of law. That age

rule

moment. As Lewis Mumford has

'The mind remains

world and passes

at a

written:

suspended; the eye looks

delicately

discriminates,

the

the stage of history. Civilization

find intellect

a creative

round,

man

beholds

inquires,

the

bound from sprawling

natural

fantasy to

continent, self/defining knowledge.'

For

thirty

centuries

the

Egyptian

carved the same hierarchic figures

nose,

same

loincloth,

same

eye,

Archaic

same

a simple exercise

torso:

repeated to the point of technical perfection.

already, even in

had

craftsman

- the same

times, the

Then,

Greek sculptor

is

observing and analysing. Even the most Archaic Greek

statue

is

because

carved by Pygmalion;

it

is

Unlike the

Luxor,

it is

realistic

it is

but because

carefully delineated

more than

it

about

is

to breathe,

instinct

with

not

life.

pharaohs on the walls

a glorified hieroglyph.

at

23

CLASSICALGREECE

So

too With the theatre.

If,

with the passing of tyranny,

custom had become law, then with the

tragedies of

Aeschylus and Sophocles what had once been

myth became drama. To

priest

-

first

one and then more were added, giving

the clash of

at

mind upon mind, and

war with

sacerdotal,

destiny.

and

rise to

man

the spectacle of

Greek drama remained formal and

with the

priests

always enthroned in the

and was ultimately absorbed

'stalls',

ritual

the single actor - originally the

both the theatre and the church, only

into the history of

to

be liberated once

again in the time of Shakespeare.

And as with

was Plato who

ment -

sculpture and drama, so with thought.

down

laid

It

the ideal condition for govern-'

that a philosopher should be a

king and a king

should be a philosopher. This condition was

fulfilled

under Solon, when law and order replaced custom.

Nature and

hubris

became

thyself,

was

began

society

to

be understood. Dislike of

- intellectual pride - and the precept 'know

the

the balanced

axioms of Greek thought; the

mind, 'nothing

The Greeks were

basic to the

to excess'.

not unaware of the problems of their

Violence was curbed but

culture.

ideal

it

existed. Slavery

economy. Cruelty was disliked but

was

dis^

regarded. Homosexuality and infanticide were defended

with cold reason.

mined

The

the integrity of

stunted role of

life.

women

under-'

The Greeks were always

conscious of the nearness of the primitive - hence their

aloofness. In so far as they were

the

Aegean,

it

was

a

aware of a world beyond

wholly barbaric world. The hosts of

Persia or the ancient dynasties of Egypt were

pale.

Greek democracy, when

reduced

itself to

it

came

to

beyond the

the point,

the votes of a few thousand Greek^born

adult males.

In the

last analysis,

attitude to the

however, Greek wisdom was an

human mind and

the

human

body.

The

Greeks had rejected the gods of Egypt, without adopting

the

24

monotheism of

the Jews.

They conceived

the gods

of Olympus not only as embodying the powers of nature.

but also as beings anatomically perfect while possessed of

human

frailty.

As

such they

made

for those statues they

made

sublimating the

the

human body

theology by

hierarchy in poetry, myth,

drama

a peninsula of jagged bays

is

and headlands, of inlets running

each inlet

their

superb sculptures, by idealizing

Greece

architecture.

The

shrines, the temples.

and by enshrining the functions

itself,

Olympic

of the whole

and

deities in

of them, and

statues

Greeks overcame the basic crudity o{

classicalgreece

far into the

mainland,

separated from the next by the mountains. The

climate produced rigorous and athletic

was almost an

invitation to carve

men;

them

the marble

as if they

were

gods.

The Greeks were

that they traded a

Euxine

a maritime people only in the sense

-

little

to the east

as far as

Spain

to the

west and the

- made poetry out of their wine^dark

sea,

and would

city

than cross the mountains.

rather sail

round the

coast

However

from

city to

they looked

inwards upon Hellas rather than out upon the great

world.

They could

never,

the

like

Romans, have

organized an empire. Even more did they look inwards

upon

the city itself- isolated

When

that

its

own arm

of the

sea.

threatened from without, as in the wars with the

Persians, the

was

upon

Greek

cities

the city states such as

could band together, but

Athens, Sparta and Corinth

were the object of patriotism and

effort.

was

the public

works of Athens, not of Greece,

civic rather than national.

Age expended

compounded of the

its

genius.

It

Greek

was upon

architecture

Periclean

it

that the

That genius was

virtue of perfectionism

and

the vice

o( self^absorption.

As with sculpture, drama, law and philosophy, so with

architecture: absolute perfection

within clearly defined

limits.

was sought, but only

The

Greeks, for instance,

were never engineers. Architecture

great families

divided into two

- the trabeated and the arcuated, beamed

and arched; Greek

refinement

is

the

architecture

is

Greek temple,

trabeated.

With

structurally,

all its

was no

25

CLASSICAL GREECE

advance upon Karnak or Stonehenge. The Greeks knew

the arch but they never exploited

it.

They never attempted

dome

cover a large space with vaults or a

to

Romans were

meticulous

to

They were

do.

fitting together

stone,

their

of stone blocks, but they were

a

means -

crude but strangely poetic religion,

to the status

skill in

hand^

mathematics

with

obsession

mystical thing - an end, not

human body

by the

fascinated

not otherwise interested in structure. Their

ling

as the

as

a

their strangely

their adoration

of the

with the consequent elevation of sculpture

of a dominant

art

.

.

.

these

were the elements

from which Greek architecture derived.

A

Greek town,

at

almost any date, must have been

just a collection of white^walled houses

tiled roofs

of low pitch,

with

like the temple.

roofs or

flat

Each house

looked inward upon a small court, and presented an

almost windowless wall to the

of

1

5

The Palace of Minos

(c.i6oo

EC)

jlights

and

The

columns, with their unusual

taper, are a

lecture

Knossos

stair^

world with regular

landings.

hot countries where there

Politics

at

had an elaborate

case, the first in the

all

supporting

street

were an

and drama an

affair

the temple as a

almost

all

affair

the

is

- the

timeless house

seclusion of

women.

of the market place - the agora -

of the open^-air theatre. This

medium

left

only

an architecture which had

of the human anatomy -

for

attributes

downward

hallmark of Cretan archie

proportion, balance, grace, precision and subtlety; but

which was

also

marmoreal and sculptural.

The

origins of

Greek

drawn from more than one

source.

that decorative but irrational affair

volutes as

lands.

its

capital - is found

From

CLASSICAL GREECE

and

The Ionic column -

architecture are uncertain,

the sea/'girt

in

with curious

spiral

an archaic form in many

kingdom of

Crete, from the

beautifully decorated apartments of the Palace of Minos

at

Knossos, there came

cision

and

and

refinement.

Greece the great

The Cretan

spreading

unfortified,

central court

to

gift

of pre/

palaces were vast

out irregularly around a

and including workshops and

There was an ornamental fa9ade

at the

storehouses.

west; the rooms

were usually frescoed, the wooden columns brightly

painted.

the

About 1450 bc, Knossos was conquered by

Mycenaean war/lords of the Peloponnese: through

them, Cretan influence passed to the mainland.

The whole

basic concept of the

columned temple

probably came from the house of the Mycenaean chief"

tain.

Mycenaean

palaces were

more formal

plan

in

than those of Crete, and stood in citadels, on strategic

hills.

Within

religious

the walls were a

and domestic. (There

number of

is

a

buildings,

parallel

in

the

conglomeration of church, chapel, tombs and palace

for the ancient

kings of Ireland, on the Great

Rock

of Cashel.) Outside the citadel were the royal tombs,

oi^

16 The

throne room at Knossos^ huilt

by the Mycenaeans after their conquest

c.

14^,0

BC.

original:

the

The hi^h^hacked

wall-painting,

hut

griffins

and plants,

fragments

is

its

drawing of wingless

refined

stiff

throne

with

is

a copy based on

1

7

The Treasury ofAtreus

BC),

(ijth century

hive tomb some

The

$0 jeet

and

other,

heads

corbelled

:

the

Mycenae

across and high.

stone courses of the vast

smoothly

the

at

a 'tholos' or bee-'

out,

one

have

doors

dome

are

over

the

triangular

the true principle of the arch

wedge-shaped voussoir

- was

-

not yet

understood

i8 Isometric

at

Mycenae.

reconstruction of the palace

A staircase

led to the throne

court (c).

round

a

(As

at

Knossos,

downward)

this lay the

hearth,

III.

1

at

is

the so-called Treasury of

A walled passage leads to a beehive/-

Mycenae.

shaped chamber about 50 by 50

megaron

corbelled vault

approached

through a columned portico and vestibule.

taper

Atreus

most famous

the great

room with four columns

central

the

twoflights (a)

room (b) and

Beyond

(d), a single

in

which

5, the

columns

all

made of

overlapping stones.

beehive tombs

tiers

feet,

rises to

of carefully cut,

The span of

(tholoi)

which

slightly

the largest o^ these

was only exceeded by

Pantheon, over a thousand years

a

later.

that of the

Among

the

buildings within the Mycenaean citadel was the chieftain's

own

house - the megaron -

much

tion of the house of Odysseus.

It

like

Homer's

descrip^

was a single simple room

with a central hearth, preceded by a vestibule and - most

significantly

a 'house'

- an outer portico with columns.

had

to

When

be built for the statue of the god or

goddess, the prototype was this chieftain's house, a

rectangular

room with

a portico.

The

architect

and

the

sculptor might, in the course of centuries, transmute this

wooden house

into a

marble shrine, but basically

it

remained a house, never a place of assembly, never a

church, and almost always upon a high place.

temple was always

set

The

apart from the town, not only by

being put in a sacred enclosure, but usually also upon a

headland, a citadel or acropolis.

The

rectangular temple with low-pitched roof

surrounding colonnade basic

upon

of Athens,

the world.

Ionic.

the

form of the Greek temple. There were many

variations

city

the peristyle

and

- thus became

the theme.

the most

is

Those temples

These

are the

On the Acropolis,

above the

famous group of buildmgs

are in

two

names given

styles,

to the

the Doric

in

and

two kinds of

whole unit -

'order' used: this

term

column with

base below and entablature above.

There

are

its

three

main

refers to the

- Doric, Ionic and

'orders'

Cormthian. The Doric Order, plamest of

simple moulded capital and no base (the

made it more

slender

and added

has a slimmer column, with, as

the

a base)

;

Romans

the Ionic

we have

has a

all,

later

Order

seen, a capital

two linked volutes; the Corinthian, with

consisting of

1^ Pottery model of a shrinefrom Argos

its

richly carved capital bristling with acanthus leaves,

was used

details

far

more by

the

Romans

and proportions of

than the Greeks.

The

the 'orders' were minutely

(late 8th century

marks

to

prescribed in the

first

Vitruvius, rather as

They became

architecture.

century

if they

ad

by the

had been

BC)

:

a single

room

fronted hy a portico of two columns,

it

a stage in the evolution from house

temple

Roman architect

laid

down

by God.

the vocabulary of the language of classical

Durmg

the last four or five

hundred

years

thousands of architects have been obsessed by these

20 The Classical Greek orders:

A, Doric; B, Ionic; C, Corinthian,

(i)

Stylobate;

shaft;

(^)

(2) attic base; (j)

(^a) abacus; (4b)

capital;

echinus; (4c) Ionic volute; ( ^d) Corin^

thian volute with acanthus leaves; (<,)

architrave; (6) triglyph; (j) metope;

(8) frieze; (g)

dentils;

(10) facia;

(11) cyma

29

:

'orders',

21,

22 The Doric Order

Paestum.

at

Below, a corner of the Archaic

'Basilica'

BC). The

columns

(mid^6th century

The

- and

and

The Greeks

races.

spreading

Greeks,

discretion

have an exonerated taper - an early use

of entasis

sometimes

capitals.

however,

They may have been

Though

compared with the Parthenon

it

includes

still

2g),

some of the same refinements

all the horizontals are slij^htly curved.

The

three

temples

at

Paestum

far

-

as the

who had come

lonians

came over

south in a

the sea

series

of

from Asia

Minor; they were Oriental, sensuous, effeminate, colour/

ful.

Character was,

as always, reflected in architecture. In

were

originally plastered, to hide flaws in the

local travertine stone

The

Dorian,

Steppes - hardy,

rigorous, practical

migrations.

One race was

away

heavy

(III.

right.

two

a tribe of northern

shepherds from as

built a century later.

flexibility,

The Dorians were

the other Ionian.

'Temple of Neptune',

them with

believed themselves to be a blend of

Virtually every thin^^ above the architrave

the

used

of intelligent design.

great artistry.

has been destroyed.

Opposite,

to the exclusion

bringing together on the Acropolis these two

styles

of

temple building - the plain, sturdy Doric and the

ornamented Ionic - the Athenians believed that

elegant,

two poles of

they were giving expression to the

nature, luxury

It is

in the

their

and abstinence.

Greek colonies

in Sicily

and on

the Italian

below Naples

Reconstruction of the vast Archaic

Temple of Artemis

we find the Doric Order in its

sternest form. The Temple of Concord at Agrigento

(f. 500-470 Bc) and the three temples at Paestum - the

coast

2J

that

were some

spaced

and Temples of Ceres and Neptune,

mid^sixth to the mid/fifth century b c -

so/called Basilica

dating from the

They

are the best^preserved examples.

are, in

a sense,

archaic - having few of the refinements of the Parthenon

Doric - but they do have a splendid, almost primeval

strength.

The columns

are stout, the capitals huge,

the stones ponderous.

all

When we

the Ionian

the

first

effect

3

Greek colonies

as early as c.540

high.

nearly 400 feet long, the

The workmanship and

technically refined;

brilliant

Artemis (the

Roman

bc, and then

56 B c, more or less on the original foundations.

The temple was

feet

overwhelming.

we turn to

of Asia Minor. At Ephesus

great temple of the goddess

rebuilt in

is

seek the Ionic style in isolation

Diana) was designed

50

The

and

it

with colour.

was

richly

columns over

carving were

ornamented, probably

at

Ephesus (begun

C.S40 BC), looking across the portico:

a triumph oj engineering - the columns

-

60 feet high and widely

as well as a rich display of the

ornate Ionic

Order

When we turn to

CLASSICAL GREECE

is

loss as

Athens

The drama of the primeval

well as gain.

gone but

on

here,

sharpened

its

own

pomt of

to a

in the fifth century b c, there

has

terms, civilization has been

perfection.

On

the Acropolis,

ancient and sacred ground, there were earlier buildings.

They were ruined

would have

seen

Then, under

its

them

stupendous

effort

was made.

itself- that high rock outside the city

sides built

kind of podium

Wars, and Socrates

blackened by smoke.

as stones

Pericles, the

The Acropolis

- had

in the Persian

up and

its

top flattened to form a

for the temples.

This separation of the

temples from the town was deliberate.

As

normally had no place in the

had the

street, as

shrines they

Roman

temple or the Christian church. Equally important,

however, was the

fact that the

temples could be

seen

from

the streets, rising above the wall of the sacred enclosure

- a continual reminder of the gods, like the medieval

bell

chiming the hours

the temple

24 Plan showing

the

major buildings

on the Acropolis at Athens (see pp.

33~'5)> ^^^ ^^^

below (h).

Theatre of Dionysus

From

the Propylaea at the

west (a),jlanked by the Pinacotheca (b)

and Temple of Nike Apteros (c), the

Sacred Way led toward a colossal

statue of

(e)

Athene

stands

goddess's

(d).

partly

old

on

temple

The Erechtheum

the

(f),

site

replaced by the Parthenon (g)

32

of the

which

was

had

a

This distant view of

profound influence upon

was designed

so that

Forgetting

minutiae,

its

for prayer.

it

its

should be 'read' from

we may

form.

It

far off.

think of the temple -

specially the bold

Parthenon -

and simple Doric

as a series

peristyle

of the

of alternating bands of light and

25 The Acropolis

natural

hill,

platform.

dark formed by the columns and the shade between

them. Oi^ course there was delicate ornament on the

Parthenon but

it

was not intended

not be seen, except from near

scale

was

and could

Here one can

up

see,

to

form

from

a

left to

Propylaea, the Erechtheum and

the Parthenon.

The simple form of the

it 'read' well from

Greek temple made

far

the intermediate

Athens stands on a

built

of

of richness, neither delicate nor bold - the Gothic

pinnacle or the

have been

Roman

useless

on

the Acropolis.

planners. In that they

in the

Corinthian Order - that would

sometimes said that the Greeks were not town^

It is

be

to. It

to be seen,

ri^ht, the

at

much

had no formally

grand manner, such

true.

Such

selfz-conscious

as

Rome

laid out cities

or Paris, this

magnificence

is

may

the attribute

of an imperial capital rather than of a small city

state.

In a higher sense, however, the Greeks were superb

designers of

cities.

We

see this in the careful

way -

geometric but not formal - that they arranged the agora

and

The

the temple groups in cities such as Miletus or Priene.

buildings on the Acropolis

sight to be almost

haphazard

would seem

in their placing.

certainly not formally planned, as the

at first

They were

Romans might

33

^.

Ui

26 Model

reconstruction of the Athenian

Acropolis, C.400

steep

approach,

BC.

This shows the

with

the

drama of the scene until

had reached the summit and

stood with the Parthenon on his

the

Erechtheum on

trance the

little

his

left.

their

arrangement and balance and

As

relationship are in fact extremely skilful.

one beheld

Propylaea

screening the full

the visitor

have liked; but

ri^^ht

At

and

them from

the Propylaea, there

There was the

the en^

Temple of Nike Apteros

acts as a foil to the larger buildinp

the entrance to the Acropolis, that

the right,

and

position

was

left

the

mass of the Parthenon on

much

smaller but

resolved by the

enormous

and helmet

Finally, the

statue of Athene

visible to sailors out

on

Parthenon, an example of

cleat/'cut sculptural precision,

it

more complex

Erechtheum. Between these two the com^

flashing spear

Aegean.

from

was no symmetry. There was balance.

large simple

the

intricate

- her

the

on

is

was

itself so

placed that

could never be seen except against the sky ... an

astonishing piece of town planning, never to be repeated.

One

pylaea.

is

ascended the Acropolis by a ramp

This building, designed by Mnesicles

not a temple.

It is

a glorified

to the

Pro^

437 b c,

gateway or porch - a

in

covered hall with a Doric portico facing the ramp, and

another opening out onto the Acropolis.

It

had an

adjoining wing, the Pinacotheca or painted gallery.

Near

by, perched

Nike Apteros 34

Callicrates in

on

a

podium, was

the

the Wingless Victory

little

Temple of

- designed by

426 B c. This was an exquisite Ionic temple

gem

in miniature, a

to the large

from

less

than

feet

1 3

long, forming a

mass of the Parthenon when both

foil

are seen

2^ View and plan of the Erechtheum

Athens, begun by Mnesicles in ^21

2"],

in

B C. The

far off.

Although

Athene

the buildings

seen from a distance,

it

on

the Acropolis could be

was only when one had passed

through the Propylaea onto the plateau that one could

right)

are

the

them

a smgle glance,

all, at

whole drama of the

and could then appreciate

scene.

It

was

brilliant stage

The most venerable temple was always the Erechtheum,

built

by Mnesicles in 421

temple.

The new Erechtheum was

the most sacred myths

Nearly

BC on

all

the

and housed

site

still

connected with

the most sacred relics.

Greek temples - although variable

were rectangular and had a surrounding

Erechtheum

is

unique.

number of rooms.

never finished,

It is

which

It

is

its

partly explains

of holies.)

It

an upstart

Athene

affair

peristyle.

all

massing;

its

-

The

it

was

unusual form.

have

shrines there. (Athene's second shrine

rather

in size

small and yet contains a

irregular in

Erechtheus, Poseidon and

- was

of an older

the

their separate

- the Parthenon

compared with

makes use of the Ionic Order

this

holy

three times.

the east,

to

it

and a rostrum with female figures

instead of columns.

The

ruins in the foreground, above, are those

of the ancient temple of Athene (f

111.

management.

to

Ionic colonnades of different

('caryatids')

see

room

and other gods. Attached

three

size,

temple contained shrines of

(in the large

24)

in

<Ml^<

.^

if^'

^m

r

in three different sizes.

most remarkable

Its

feature

the so/'called Caryatid Portico, not truly a portico at

but a rostrum. Sculptured maidens, 7

difficulty

his

IS

The

overcome.

skilfully

maidens in such an easy pose

which

tablature

The Caryatid

burden.

force

they carry

on

Portico

inherent

sculptor has carved

marble

that the

en-'

heads seems no

their

is

all,

9 inches high,

The obvious

of columns.

place

the

take

feet

is

a very ornate tour de

which, had the Erechtheum ever been

finished,

might have been a jewel in the centre of a long blank

wall.

The Parthenon, like the Erechtheum, replaced an older

temple, but on a new site a little to the south of the older

one. The Parthenon was dedicated to Athene Parthenos

- the virgin Athene

adult

and

who had

been miraculously born,

armed, from the head of Zeus.

fully

447 bc, by the

begun

in

crates.

Phidias was the master sculptor.

The

stylobate,

Parthenon stands

228

feet

on which

long and loi

was

and Calli^

architects Ictinus

or stepped plattorm,

is

It

wide.

feet

the

The

jo North porch

peristyle

which ran

56 columns,

columns

at

all

all

round the temple consisted of

of the Doric Order. There are eight

each end (instead of the usual

six), leaving a

the

top

in

columns,

widely

columns on each

giving a central

entrance.

The

side (the south side

column

is

There were 17

now incomplete),

suggestive of 'side'

portico at each end

or

fj^ures

28).

Slender

hi^h,

are

25 feet

spaced,

Above them

space opposite the central entrance.

of the Erechtheum (at

III.

an

^ivin^

in the

Ionic

unusually

airy

effect.

frieze white marble

were attached

to

a grey

stone

background

no

was two columns

deep, giving greater shelter at the entrance.

The

shrine

2g,

ji

View of the Parthenon from

the

north-west (opposite), and plan. Begun

in

its

44^

BC by Ictinus and Callicrates,

simplicity

Within

divided

by

ambulatory

at the

is

deceptive (see p.

40).

the temple the shrine faced east,

columns

(III.

west end-

j2).

left

into

A

nave

and

columned room

- served as

a treasury

37

^2

Recofistruction of the sanctuary in

the Parthenon, looking towards the ^old

and

ii'ory statue

of Athene by Phidias.

An

ambulatory was screened off by a

double tier of Doric columns. The lights

in£

arrangements and roofing are un^

known:

here the artist suggests a cof"

fered wooden

ceiling,

and sunlight entering

by the eastern door alone

or naos of the older

Greek

feet

and archaic Parthenon had been 100

long and had, therefore, been called the

Hecatompedon;

this

name was

transferred to the naos

of the new temple. This was about 63

with columned

aisles.

It

feet

contained,

wide, probably

in

roughly the

position where the altar stands in a Christian church,

the 40>'foot statue of the goddess

Athene

gold by Phidias. Also enclosed in the

to the jtiflfiij^he

44

feet.

in ivory

cella^

and

in addition

temple had another room, about 63 by

This was called iht Parthenon and gave

its

name

The word means virgin, and this

room may have been the home of the virgins who cared

to the entire building.

for the

temple and tended

hieratic treasury

38

with a bronze

its

lamps.

of the Acropolis,

grille.

its

It

was

also the

doors being closed

The Parthenon

has no

windows.

How was

it lit

?

This

classical Greece

has always been a controversial matter. Since the seven/

teenth century the building has been too ruinous to

allow any theory to be

The

such theories.

There

tested.

however, three

are,

hypethral theory

large rectangular hole in the roof immediately

This seems unlikely. There

shrine.

arrangement in the floor

though

relatively little

the hole

no

above the

signs of

any

might be in Athens. Also

there

would cause an ugly break

The second

perfect.

are

a

draining off rain-water -

for

building which had, above

was

that there

is

in the roof line of a

all

things, to be aesthetically

is

that the roof of the Par/'

theory

thenon, and of other temples, was of timber with thin

roofing

of Parian marble or alabaster. These,

slabs

though not transparent, would be

lucent to give a diffused

such roofing slabs

glow within

and

exist

was no

this

is

sufficiently

trans^

the shrine.

Many

an

attractive theory

below the roof The

assuming that

there

third theory

that the great eastern doors

and

is

that the

Greek sunshine gave

the horizontal

upon

ceiling

beams of the

all

rising

the light

it

was on

dim and holy

the outside of the

Parthenon that the Greek genius discovered

The

Parthenon today

the limitations

clarify

limitations

it

were

and

hall.

just a

It

lies

ideals

detail

was not