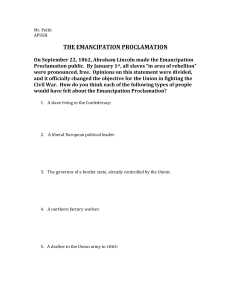

Juneteenth and U.S. Civil War Policy on Slavery “Juneteenth”- June 19th, 1865, Galveston, Texas is the date and the location where U.S. troops liberated enslaved persons, who had been nominally freed over two years earlier by Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. Three months before June 19th, in April, Lee surrendered to Grant and Lincoln was assassinated. Juneteenth does not commemorate the emancipation of the last black Americans held as slaves in the U.S. However, the commemoration of Juneteenth serves as a marker that helps contextualize the process of emancipation in the U.S. during the Civil War. Juneteenth’s most obvious point is that the Emancipation Proclamation did not liberate all the slaves, nor was it intended to. But I am getting ahead of myself. This monograph is an explanatory list that can serve as a tool, as an instrument for you and your students to historically contextualize the events of June 19, 1865. We shall focus this summary on the policies of the U.S. government under President Lincoln. The position of the Republican Party’s candidate, Abraham Lincoln, in the 1860 presidential election was to oppose the creation of new slave states. Furthermore, the Republicans stated that they would not attempt to abolish slavery in the existing slave states. The Republican position, however, meant that in the future, free states would have a great majority over the slave states in both houses of congress. Southerners claimed that a free state majority, combined with a Republican president, meant a loss of legislative power for the slave states. For decades, the South had sought to defend its economic interest, such as import tariffs, with the threat of secession. Now, for the record, the threat of session had been made by some Northeastern leaders during the War of 1812-14. Earlier from 1804 to 1807, Vice-President Aaron Burr plotted with others to secede a western portion of the US and northern New Spain to create a new republic. But returning to the topic of Southern session, the slave-owning plantation elites (cotton, tobacco, rice, sugar) had over the course of two centuries convinced and gradually radicalized the majority of the white middle-class, non-slave-owning small farmers, and free white workers into believing that they were one group, one region that had to defend its economy, political power, and natural right to own slaves as property. Fueling the belligerent spirit supporting this identity concept was the Southern culture of fighting, dueling, and just threating a duel to intimidate the other party to backdown. Dueling, violence, and intimidation had become a regular affair in the congress. See Freeman’s The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to the Civil War (2018). Add to this outlook the actions of John Brown in the late 1850s and you get a more complete perception and attitude of the general white Southern population. Additionally, for decades they feared a Haitian style slave rebellion. Indeed, in this context, from 1860 to 1861, many Southerners came to support secession as the only way to defend their supremacy. They believed that a Republican president and free state congressional majority (1860= 18 free and 15 slave states) that would prevent the creation of new slave states would tip the balance of power established by the Missouri Compromise in 1820. They claimed this trend of growing Northern power would embolden abolitionist and give the free states the votes necessary to abolish slavery in the U.S. This was seen as an imposition on the South by outsiders, by the Northern and Pacific Coast states. Furthermore, the emancipation of slaves without compensation to the owners could be a loss of a billion dollars. Additionally, they asserted that only a state could abolish slavery and not the federal government, that states were not prevented by the U.S. Constitution from seceding; and that slavery was a natural condition and property right based on white supremacy. My view is that this phenomenon is one of most consequential examples of social conditioning, peer pressure, and institutionalized manipulation by a minority to secure the radicalized support of a majority for specific objectives. As an aside, you may find it interesting to research pro-Confederate “colored creole” slaveowners in Louisiana and Confederate Native American units in the Indian Territory. Following the November election of 1860, the process of secession and formation of the Confederate States of American ran from December 20, 1860 to May 20, of 1861. The South had initiated hostilities on January 9, 1861 by firing against the troop transport ship Star of the West and more directly with the bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Not all slave states joined, or were allowed by the federal government to join the Confederacy. These “loyal” slave states were known as “border states” and included Missouri, Kentucky, the new state of West Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware. And let us not forget that Washington D.C. had legalized slavery, although in 1850 it became illegal to buy and sell slaves in city limits. Returning to the original point, the Republican position in 1860 was not to free slaves in states where it was legal. Evidently, one can argue that the Civil War propelled the processes toward emancipation. This leads us to the U.S. policy on slavery in the wake of Southern hostilities. The Crittenden-Johnson Resolution of July 1861 stated that the aim of the war was to preserve the unity of the U.S. by suppressing the secessionist rebellion. It was not a war to liberate slaves. Republicans and loyal Democrats feared that the white population would not support the war effort if the emancipation of slaves were a policy objective. Furthermore, the Republicans were trying to be consistent with their political platform. However, the Confiscation Acts of 1861 and 1862, over time provided a clever opportunity to emancipate some slaves in Confederate controlled areas by initially confiscating them from rebel owners. Under these acts, a slave that had fought or served to support the military activities of the Confederate forces would be confiscated and freed. It was hoped that he would serve in the U.S. armed forces against the rebellion. Other slaves, men, women and children, who were found in rebel areas or ran away seeking refuge among U.S. forces were confiscated as enemy property “contraband” and could be held in bondage by the local commander as necessary labor for the war effort. Ironically, this made the U.S. government the owner of confiscated slaves. But later, U.S. commanders opted to freeing slaves and recruiting the men for military service, for which many volunteered for enthusiastically. We hope that you will research the history of the valiant and indefatigable Civil War service of the black soldiers and sailors of the U.S. forces. Returning to the topic of the Confiscation Acts, they were not only a vehicle to harm the already blockaded South, but to emancipate part of the enslaved population. Let us also consider that a commander may not want to use material army resources to care for confiscated slaves, when he could otherwise free them. The next major development in the policy regarding the emancipation of slaves were Lincoln’s executive orders of September 22, 1862 and January 1, 1863. The Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation of September 22nd announced that all slaves in Confederate controlled areas would be declared free by Presidential order on January 1, 1863. This would hopefully incentivize the Southerners to surrender, even if done in a piecemeal manner, such as parts of states. Note, what Lincoln was telling the Southerners: surrender, become loyal, and you will be able to keep your slaves. The Southern states did not surrender. The Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863 went into effect. Great battles were to follow- Vicksburg and Gettysburg. There was also the Manhattan anti-draft, anti-rich, and anti-black uprising in July 1863. The war continued into 1865 with hostilities ending from April through May accompanied by Southern surrenders over the course of the year. President Andrew Johnson Proclaimed the Civil War over in August 1866, nine months after the abolition of the slavery by the 13th Amendment. We shall refrain from discussing the other motivations and consequences of the Emancipation Proclamation. Nevertheless, we strongly encourage you to research them. Suffice it to say here that: (1) The Emancipation Proclamation did not liberate all the slaves in the U.S. or in the Confederacy (C.S.), of course, not recognized by the U.S. (a) It did not apply to or free the slaves in those slave states that remained or were forced to remain loyal to the U.S.; such as Missouri, Kentucky, the new West Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware. The slaves of Washington D.C. had already been emancipated in April 1862. But why not liberate slaves in the border states? For one thing, the economy had to keep running in these loyal states. Furthermore, Lincoln did not wish to push some of the slave-owners in these states to switch-sides and support the C.S. (b) The Emancipation Proclamation did not free anyone still held as a slave in those parts of a rebel state that had been seized and occupied by the U.S. armed forces prior to January 1, 1861. Recall, the Proclamation only applied to areas under Confederate military and governmental control. Therefore, legally a slave could be held as confiscated property by the U.S. armed forces in those areas. Following the great battles of 1862, Tennessee came under U.S. military occupation. The Emancipation Proclamation did not apply to that state. The Military Governor of Tennessee, future Vice-President and President of the U.S., Andrew Johnson, freed his own slaves in August 1863 and abolished slavery in that occupied former Confederate state in October 1864, well after the Emancipation Proclamation. We strongly encourage you to research Andrew Johnson’s presidency. (c)The Proclamation only applied to slaves held in areas under Confederate control, meaning that those persons were nominally free, but not physically so. These “freedmen” would have to: (i) runway on their own from their enslavers evading the Confederate police and military patrols to reach U.S. units or vessels. (ii) wait for U.S. forces to capture the area and be liberated. This is what happened to those who were still in bondage and were liberated in Galveston on June 19, 1865. During the war, Lincoln’s generous Ten Percent Plan encouraged Southerners who took a loyalty oath to write a new state constitution that abolished slavery in their state. Therefore, a former rebel state would, by its own state constitution, emancipate its slaves rather than the federal government doing so- an act of state sovereignty. By this means, the Reconstructed state of Louisiana abolished slavery in 1864. When did slavery end in the “border states”? Maryland’s new constitution of 1864 abolished slavery. West Virginia was invaded by the U.S. Army early in the war. It became an occupied zone. However, there was a strong anti-Confederate faction of local leaders that, with federal support, seceded from the Confederate state of Virginia. Therefore, it was in U.S. loyalist hands. Most of West Virginia was not subject to the Emancipation Proclamation (49 out of 50 counties). As a condition for U.S. statehood, Lincoln insisted on a form of gradual emancipation following statehood. Here is where the March 1863 Willey Amendment to the state constitution came into play. Discussing this matter in general terms, West Virginia adopted a program of gradual and generational emancipation. The first slaves would have been freed in 1867. Note, that the Willey Amendment was passed after the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect. Nevertheless, as the Civil War was coming to an end and in anticipation of the proposed 13th Amendment abolishing slavery, the West Virginian state legislature abolished slavery in February 1865. The slaves of the border states of Kentucky and Delaware were not freed until the passage of the 13th Amendment on December 6, 1865, nearly six months after “Juneteenth” and two years after the Emancipation Proclamation. As a sidenote worthy of deconstruction, Mississippi did not ratify the 13th Amendment until 1995 and did not file its ratification until February, 2013. We already mentioned the emancipation of slaves in the District of Columbia on April 16, 1862- a municipal holiday in that city called Emancipation Day. Interestingly, the liberation of slaves in D.C. was executed with government compensation of no more than $300 to each owner and $100 paid to any D.C. freedman who volunteered to leave the U.S. and settle in another country. Forms of slavery persisted and continue to exist in the U.S. and other countries in illegal and disguised ways. In the free state of California during the Gold Rush and the Civil War, an adult white male could legally serve as the guardian to indigenous children “wards” based solely on his own testimony under oath. He would simply say that he had the child’s parental consent or that the children were orphans. The latter could have been true, due to the practices of state hired agents who sometimes killed “hostiles” for privately paid scalp bounties, rather than relocate them to army reservations. As for the children’s parental consent, well frankly it was not necessary since according to California law, only a white man’s testimony would have counted. Native Americans or Chinese could not testify against a white person. These sort of legal guardian arrangements, documented in Heizer and Almquist’s The Other Californians (1977), provided a legal way for whites to use indigenous labor. We also had the illegal enslavement and forced labor conducted by some shipping companies in the form of “Shanghaiing” a sailor. Woe to the unsuspecting visitor to a Portland, San Francisco, or Seattle tavern. Then there was a practice that is sometimes discussed as a form of temporary enslavement: namely, prison labor assigned to private enterprises. This is justified often as punishment or a form a rehabilitation. That topic is itself another full discussion subject to debate. It is undeniable, however, that our country continues to have clandestine slave immigrant laborers and sex slaves under different conditions of bondage. Today, there are people being illegally captured, restrained, guarded, transported, physically tortured, and forced to perform acts against their will for the economic benefit and/or wishes of others. Illegal slavery persists and liberations occur. We hope that this survey of the U.S. policy regarding slavery during and immediately following the Civil War will serve as a useful instrument for you and your students to contextualize Juneteenth and explore related topics in greater depth. On behalf of the History Department, Walter