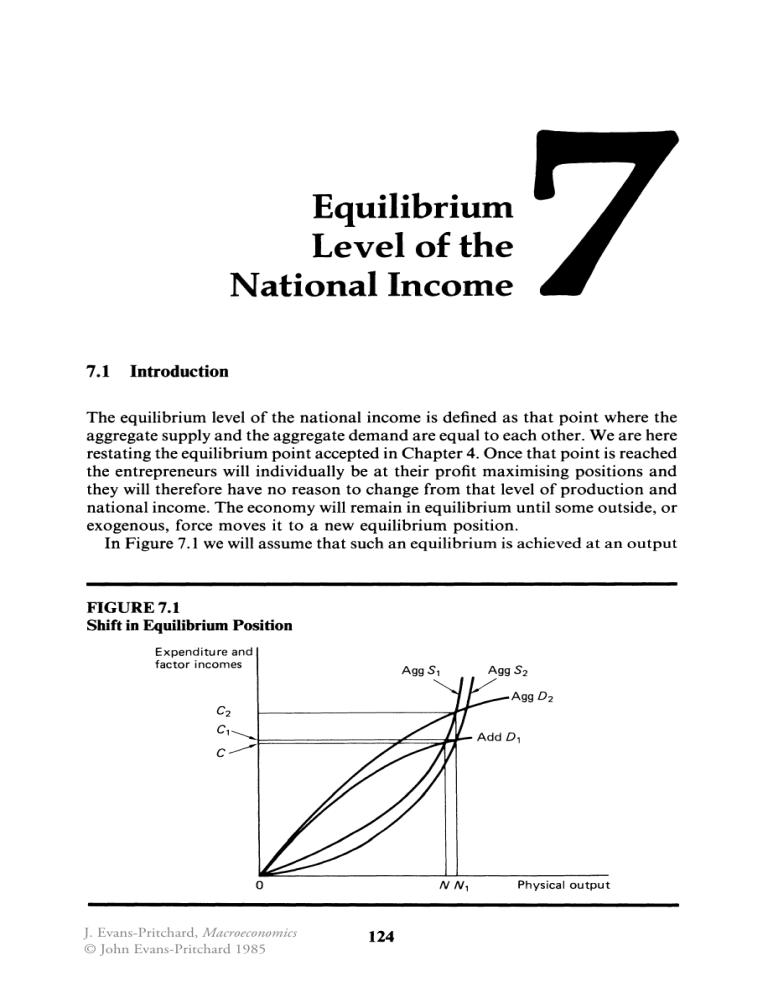

Equilibrium Level of the National Income 7.1 Introduction The equilibrium level of the national income is defined as that point where the aggregate supply and the aggregate demand are equal to each other. We are here restating the equilibrium point accepted in Chapter 4. Once that point is reached the entrepreneurs will individually be at their profit maximising positions and they will therefore have no reason to change from that level of production and national income. The economy will remain in equilibrium until some outside, or exogenous, force moves it to a new equilibrium position. In Figure 7.I we will assume that such an equilibrium is achieved at an output FIGURE7.1 Shift in Equilibrium Position Expenditure and factor incomes AggS 1 0 J. Evans-Pritchard, Macroeconomics © John Evans-Pritchard 1985 NN 1 124 Physical output Equilibrium Level of the National Income 125 of 0 N. The revenue from sales or 'costs' of all factor incomes is OC. Supply and demand are equal at this level and the circular flow of income will continue at OC until it is interrupted. If we observe that the output level, or the cost level, or both, have changed, then this is only possible if either the aggregate supply and/or the aggregate demand have changed. If we know that the output has risen to ON1 the system can only have moved to such an output by either an increase in supply to Agg S 2 or an increase in demand to Agg D2, or a combination of both. To discover which is the cause all that is required is to check what has happened to the 'cost' of the output. Has it risen to C 1 or to C2, or somewhere in between? The ease, or difficulty, with which we could discover the actual cause of a change in output will depend on how accurately we had drawn the lines on the graph in the first place. Even then the lines themselves would not tell us which factor in the supply or the demand had been responsible for the change. To determine that, we need to look in much greater depth at what the aggregate demand and supply are made up from. That should guide us towards the answer to the question 'What makes the equilibrium position of the economy change?' It will also, however, raise some of the central problems of theoretical economics, and especially the problem of how different or similar the theories actually are. The sort of problem that we face can be illustrated by this question: 'When a man receives a wage increase, is that a change in the costs of production, thereby decreasing supply, or is it a change in his income, thereby increasing demand?' As there are thousands of such dichotomies, the theoretical answers provided here will do little to stop the Keynesian and Classical debate of what could happen in the real world. 7.2 Aggregate Supply - Composition We have already seen in Chapter 4 (p. 65) that the aggregate supply is the total of factor incomes that firms will pay out in order to produce a specific output of goods and services. Over any particular period of time it is therefore an expression of the total of factor incomes earned in that period of time: it is the GNY. At the same time it is also how we measure the goods and services produced in that period of time: it is the GNP. It is in this physical sense of the quantity of production that we are most interested, because that not only provides us with our standard of living but it also determines the level of employment. The use of factor incomes simply gives us a standard unit in which to add it all up. Aggregate supply, then, is the same thing as the goods and services supplied at any particular level of national income. Components ofaggregate supply A breakdown of the GNP figures for any particular year will identify where the