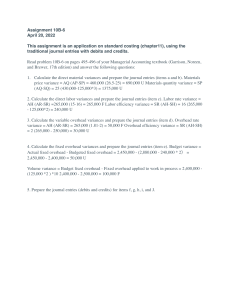

12.27 Materials and manufacturing labour variances Consider the following data collected for Tents‘n’Stuff Pty Ltd: Direct materials $200 000 214 000 Cost incurred: actual inputs × actual prices Actual inputs × standard prices Standard inputs allowed for actual output × standard prices Direct manufacturing labour $90 000 86 000 225 000 80 000 Required Calculate the price, efficiency and flexible-budget variances for direct materials and direct manufacturing labour. Solution: Materials and manufacturing labour variances Direct materials Actual Costs Incurred (Actual Input Qty × Actual Price) $200 000 $14 000 F Price variance Actual Input Qty × Budgeted Price $214 000 Flexible Budget (Budgeted Input Qty Allowed for Actual Output × Budgeted Price) $225 000 $11 000 F Efficiency variance $3000 F Flexible-budget variance Direct manufacturing labour: $90 000 $86 000 $80 000 $4 000 U $6 000 U Price variance Efficiency variance $10 000 U Flexible-budget variance 12.29 Price and efficiency variances, journal entries Whangaratta Ltd manufactures ceramic lamps. It has set up the following standards per finished unit for direct materials and direct manufacturing labour: Direct materials: 10 kg at $4.50 per kg Direct manufacturing labour: 0.5 hours at $30 per hour $45.00 15.00 The number of finished units budgeted for January was 5 000; 4 550 units were actually produced. Actual results in January were: Direct materials: 45 055 kg used Direct manufacturing labour: 2 250 hours $70 875 Assume that there was no beginning inventory of either direct materials or finished units. During the month, materials purchases amounted to 50 000 kg, at a total cost of $232 500. Price variances are isolated upon purchase. Efficiency variances are isolated at the time of usage. Required 1. Calculate the January price and efficiency variances of direct materials and direct manufacturing labour. 2. Prepare journal entries to record the variances in requirement 1. 3. Comment on the January price and efficiency variances of Whangaratta Ltd. 4. Why might Wangaratta Ltd calculate direct materials price variances and direct materials efficiency variances with reference to different points in time? Solution: Price and efficiency variances, journal entries 1. Direct materials and direct manufacturing labour are analysed in turn: Actual Costs Incurred (Actual Input Qty × Actual Price) Direct Materials (100 000 × $4.65a) $465 000 Actual Input Qty× Budgeted Price Purchases Usage (100 000 × $4.50) (98 055 × $4.50) $450 000 $441 247.50 $15 000 U Efficiency variance Direct Manuf. Labour (4 900 × $31.50b) $154 350 b 2. (5 000 × 10 × $4.50) $225 000 $216 247.50 U Price variance (4 900 × $30) $147 000 (0.5 × 5000× $30) $75 000 $7 350 U Price variance a Flexible Budget (Budgeted Input Qty Allowed for Actual Output × Budgeted Price) $72 000 U Efficiency variance $232 500 ÷ 50 000 = $4.65 $154 350 ÷ 4 900 = $31.50 Direct Materials Control Direct Materials Price Variance Accounts Payable or Cash Control Work-in-Process Control Direct Materials Efficiency Variance Direct Materials Control Work-in-Process Control Direct Manuf. Labour Price Variance Direct Manuf. Labour Efficiency Variance Wages Payable Control 450 000 15 000 225 000 216 247.50 75 000 7 350 72 000 465 000 441 247.50 154 350 3. All variances are unfavourable. 4. The purchasing point is where responsibility for price variances is most often found. The production point is where responsibility for efficiency variances is most often found. Whangaratta Ltd may calculate variances at different points in time to tie in with these different responsibility areas. Furthermore, determining the price variance based on purchase quantity identifies the variance more quickly so that it can be tracked to specific purchase decisions. 18.18 Capital budget methods, no income taxes Yummy Candy Ltd is considering purchasing a second chocolate dipping machine in order to expand their business. The information Yummy has accumulated regarding the new machine is: Cost of the machine Increased contribution margin Life of the machine Required rate of return $80 000 $15 000 10 years 6% Yummy estimates that they will be able to produce more candy and thus increase their contribution margin each year. They also estimate that there will be a small disposal value of the machine but the cost of removal will offset that value. Ignore income tax issues in your answers. Assume that all cash flows occur at year-end except for initial investment amounts. Required 1. Calculate the following for the new machine: a. net present value b. payback period c. internal rate of return d. accrual accounting rate of return based on the net initial investment (assume straightline depreciation). 2. What other factors should Yummy Candy consider in deciding whether to purchase the new machine? Solution: (22–25 min.) Capital budget methods, no income taxes 1. a. The table for the present value of annuities (Appendix B, Table 4) shows: 10 periods at 6% = 7.360 Net present value= A$15 000× (7.360) – A$80 000 = A$110 400 – $80 000 = A$30 400 If using Excel: NPV = A$30 401 b. Payback period= A$80 000 ÷ A$15 000 = 5.333 years c. Internal rate of return: A$80000 =Present value of annuity of A$15000 at R% for 10 years, or what factor (F) in the table of present values of an annuity (Appendix B, Table 4) will satisfy the following equation. A$80 000= A$15 000F F = $80 000 $15 000 = 5.333 On the 10-year line in the table for the present value of annuities (Appendix B, Table 4), find the column closest to 5.333; it is between a rate of return of 12% and 14%. Interpolation is necessary: 12% IRR rate 14% Difference Internal rate of return= 12% +[ 5.650 –– 5.216 0.434 0.317 ](2%) 0.434 Present Value Factors 5.650 5.333 –– 0.317 = 12% + (0.73) (2%) = 13.46% If using Excel: IRR = 13.43% d. Accrual accounting rate of return based on net initial investment: Net initial investment = A$80 000 Estimated useful life = 10 years Annual straight-line depreciation = A$80 000 ÷ 10 = A$8 000 Accrual accounting rate of return = Increase in expected average annual operating income Net initial investment = ($15 000 – 8 000)/80 000 = 7 000/80 000 = 8.75% Note how the accrual accounting rate of return, whichever way calculated, can produce results that differ markedly from the internal rate of return. 2. Other than the NPV, rate of return and the payback period on the new computer system, factors that Staples should consider are: Issues related to the financing the project, and the availability of capital to pay for the system. The effect of the system on employee morale, particularly those displaced by the system. Salesperson expertise and real-time help from experienced employees is crucial to the success of a hardware store. The benefits of the new system for customers (faster checkout, fewer errors). The upheaval of installing a new computer system. Its useful life is estimated to be 3 years. This means that Staples could face this upheaval again in 3 years. Also ensure that the costs of training and other ‘hidden’ start-up costs are included in the estimated A$275000 cost of the new computer system. 18.22 Comparison of projects, no income taxes Santolis is a rapidly growing eco-technology company that has a required rate of return of 14%. It plans to build a new facility in Adelaide. The building will take two years to complete. The building contractor offered Santolis a choice of three payment plans, as follows: Plan I. Payment of $175 000 at the time of signing the contract and $4 700 000 upon completion of the building. The end of the second year is the completion date. Plan II. Payment of $1 625 000 at the time of signing the contract and $1 625 000 at the end of each of the two succeeding years. Plan III. Payment of $325 000 at the time of signing the contract and $1 500 000 at the end of each of the three succeeding years. Required 1. Using the net present value method, calculate the comparative cost of each of the three payment plans being considered by Santolis. 2. Which payment plan should Santolis choose? Explain. 3. Discuss the financial factors, other than the cost of the plan, and the non-financial factors that should be considered in selecting an appropriate payment plan. Solution: (30 min.) Comparison of projects, no income taxes 1. Total Present Value Present Value Discount Factors at 14% Year 0 1 2 3 Plan I A$ (175000) 1.000 (3 614 300) 0.769 A$(3 789 000) With Excel this is A$3 616 497 A$(175 000) A$(4 700 000) Plan II A$(1 625000) 1.000 (1425 125) 0.877 (1 249 625) 0.769 A$(4 299750) With Excel A$4 300 823 A$(1 625 000) A$(1 625 000) A$(1 625 000) Plan III A$(325 000) 1.000 (1315 500) 0.877 (1153 500) 0.769 (1012 500) 0.675 A$(3 806 500) With Excel A$3 807 448 A(325 000) A$(1500 000) A$(1 500 000) A$(1 500 000) Summary: Plan I: (A$3 789 000) Plan II: (A$4 299 750) Plan III: (A$3 806 500) 2. Plan I has the lowest net present value cost. Plan I is the preferred one on financial criteria. 3. Factors to consider, in addition to NPV, are: a. Financial factors including: Competing demands for cash. Availability of financing for project. Note that Plan III is very close in terms of NPV but is a more even cash flow across three years. b. Non-financial factors including: Risk of building contractor not remaining solvent. Plan II exposes Santolis most if the contractor becomes bankrupt before completion because it requires more of the cash to be paid earlier. Ability to have leverage over the contractor if quality problems arise or delays in construction occur. Plans I and III give Santolis more negotiation strength by being able to withhold sizable payment amounts if, say, quality problems arise in Year 1. Investment alternatives available. If Santolis has capital constraints, the new building project will have to compete with other projects for the limited capital available. 8.17 ABC, hierarchy of activities (CMA, adapted) Vineyard Test Laboratories does heat testing (HT) and stress testing (ST) on materials, and operates at capacity. Under its current costing system, Vineyard aggregates all operating costs of $1 190 000 into a single overhead cost pool. Vineyard calculates a rate per test-hour of $17 ($1 190 000 ÷ 70 000 total test-hours). HT uses 40 000 test-hours, and ST uses 30 000 test-hours. Gary Celeste, Vineyard’s management accountant, believes that there is enough variation in test procedures and cost structures to establish separate costing and billing rates for HT and ST. The market for test services is becoming competitive. Without this information, any mis-costing and mis-pricing of its services could cause Vineyard to lose business. Celeste divides Vineyard’s costs into four activity-cost categories: a. Direct-labour costs, $146 000. These costs can be directly traced to HT, $100 000, and ST, $46 000. b. Equipment-related costs (rent, maintenance, energy and so on), $350 000. These costs are allocated to HT and ST on the basis of test-hours. c. Set-up costs, $430 000. These costs are allocated to HT and ST on the basis of the number of set-up hours required. HT requires 13 600 set-up hours, and ST requires 3 600 set-up hours. d. Costs of designing tests, $264 000. These costs are allocated to HT and ST on the basis of the time required for designing the tests. HT requires 3 000 hours, and ST requires 1 400 hours. Required 1. Classify each activity cost as output-unit-level, batch-level, product-sustaining, or organisation-sustaining. Explain each answer. 2. Calculate the cost per test-hour for HT and ST. Explain briefly the reasons why these numbers differ from the $17 per test-hour that Vineyard calculated using its traditional costing system. 3. Assess the accuracy of the product costs calculated using the current costing system and the ABC system. How might Vineyard’s management use the hierarchy and ABC information to better manage its business? Solution: (25 min.) ABC, hierarchy of activities 1. Output unit-level costs a. Direct-labour costs, $146 000 b. Equipment-related costs (rent, maintenance, energy, and so on), $350 000 These costs are output unit-level costs because they are incurred on each unit of materials tested, that is, for every hour of testing. Batch-level costs c. Set-up costs, $430 000 These costs are batch-level costs because they are incurred each time a batch of materials is set up for either HT or ST, regardless of the number of hours for which the tests are subsequently run. Product-sustaining costs d. Costs of designing tests, $264 000 These costs are product-sustaining costs because they are incurred to design the HT and ST tests, regardless of the number of batches tested or the number of hours of test time. 2. Heat Testing (HT) Total (1) Direct labour costs (given) Equipment-related costs $5 per hour* 40 000 hours $5 per hour* 30 000 hours Set-up costs $25 per set-up-hour† 13 600 set-uphours $100 000 Per Hour (2) = (1) 40 000 hrs $2.50 200 000 340 000 Total costs 180 000 $820 000 Total (3) $ 46 000 Per Hour (4) = (3) 30 000 Hrs $1.53 5.00 150 000 5.00 90 000 3.00 84 000 2.80 $370 000 $12.33 8.50 $25 per set-up-hour† 3 600 set-uphours Costs of designing tests $60 per hour** 3 000 hours $60 per hour** 1 400 hours Stress Testing (ST) 4.50 $20.50 *$350 000 (40 000 + 30 000) hours = $5 per test-hour † $430 000 (13 600 + 3 600) set-up hours = $25 per set-up-hour **$264 000 (3 000 + 1 400) hours = $60 per hour At a cost per test-hour of $17, the traditional costing system under-costs heat testing ($20.50) and over-costs stress testing ($12.33). The reason is that heat testing uses direct labour, setup, and design resources per hour more intensively than stress testing. Heat tests are more complex, take longer to set up and are more difficult to design. The traditional costing system assumes that testing costs per hour are the same for heat testing and stress testing. 3. The ABC system better captures the resources needed for heat testing and stress testing because it identifies all the various activities undertaken when performing the tests and recognises the levels of the cost hierarchy at which costs vary. Hence, the ABC system generates more accurate product costs. Vineyard’s management can use the information from the ABC system to make better pricing and product mix decisions. For example, it might decide to increase the prices charged for the more costly heat testing and consider reducing prices on the less costly stress testing. Vineyard should watch if competitors are underbidding Vineyard in stress testing and causing it to lose business. Vineyard can also use ABC information to reduce costs by eliminating processes and activities that do not add value, identifying and evaluating new methods to do testing that reduce the activities needed to do the tests, reducing the costs of doing various activities, and planning and managing activities. 8.19 Traditional cost drivers and ABC cost drivers Roadster Pty Ltd designs and produces automotive parts. In 2018, actual variable production overhead is $280 000. Roadster’s costing system allocates variable production overhead to its three customers based on machine-hours, and prices its contracts based on full costs. One of its customers has regularly complained of being charged non-competitive prices, so Roadster’s management accountant, Matthew Draper, realises that it is time to examine the consumption of overhead resources more closely. He knows that there are three main departments that consume overhead resources: design, production and engineering. He interviews the department personnel and examines time records, which yield the following information: Required 1. Calculate the production overhead cost allocated to each customer in 2018 using machinehours as the cost driver. 2. Calculate the production overhead cost allocated to each customer in 2018 using departmentbased production overhead rates. 3. Comment on your answers in requirements 1 and 2 and identify which customer was most likely to complain about being overcharged in the traditional system. If the new departmentbased rates are used to price contracts, identify the customer(s) that are most likely to be unhappy. Suggest how Matthew should respond to these concerns. 4. Suggest to Roadster how it might further use the information available from its departmentby-department analysis of production overhead costs. 5. Roadster’s managers are wondering if they should further refine the department-by-department costing system into an ABC system by identifying different activities within each department. Outline the conditions under which it would or would not be worthwhile to further refine the department costing system into an ABC system. Solution: (20 min.) Traditional cost drivers and ABC cost drivers 1. Actual plant-wide variable MOH rate based on machine hours, $280 000 5 000 $56 per machine hour Southern Motors Variable production overhead, allocated based on machine hours ($56 300; $56 3 700; $56 1 000) $16 800 Caesar Motors $207 200 Jupiter Auto $56 000 2. Design Production Engineering MOH in 2017 $ 35 000 25 000 220 000 Total Driver Units 500 500 5 000 Rate $70 $50 $44 per CAD-design hour per engineering hour per machine hour Total $280 000 Southern Motors Design-related overhead, allocated on CADdesign hours (150 $70; 250 $70; 100 $70) Production-related overhead, allocated on engineering hours (130 $50; 100 $50; 270 $50) Engineering-related overhead, allocated on machine hours (300 $44; 3 700 $44; 1 000 $44) Total Caesar Motors Jupiter Auto $10 500 $ 17 500 $ 7 000 $ 35 000 6 500 5 000 13 500 25 000 13 200 $30 200 162 800 $185 300 44 000 $64 500 220 000 $280 000 Total 3. Southern Motors Caesar Motors Jupiter Auto a. Department rates (Requirement 2) $30 200 $185 300 $64 500 b. Plant-wide rate (Requirement 1) $16 800 $207 200 $56 000 Ratio of (a) ÷ (b) 1.80 0.89 1.15 The production overhead allocated to Southern Motors increases by about 80% under the department rates, the overhead allocated to Caesar decreases by about 11%, and the overhead allocated to Jupiter increases by about 15%. The three contracts differ sizably in the way they use the resources of the three departments. The percentage of total driver units in each department used by the companies is: Department Design Engineering Production Cost Driver CAD-design hours Engineering hours Machine hours Southern Motors 30% 26 6 Caesar Motors 50% 20 74 Jupiter Auto 20% 54 20 The Southern Motors contract uses only 6% of total machines hours in 2018, yet uses 30% of CAD design-hours and 26% of engineering hours. The result is that the plant-wide rate, based on machine hours, will greatly underestimate the cost of resources used on the Southern Motors contract. This explains the 80% increase in indirect costs assigned to the Southern Motors contract when department rates are used. The Jupiter Auto contract also uses far fewer machine-hours than engineering-hours and is also under-costed. In contrast, the Caesar Motors contract uses less of design (50%) and engineering (20%) than of machine-hours (74%). Hence, the use of department rates will report lower indirect costs for Caesar Motors than does a plant-wide rate. Caesar Motors was probably complaining under the use of the traditional system because its contract was being over-costed relative to its consumption of MOH resources. Southern and Jupiter, on the other hand, were having their contracts under-costed and underpriced by the traditional system. Assuming that Roadster is an efficient and competitive supplier, if the new department-based rates are used to price contracts, Southern and Jupiter will be unhappy. Roadster should explain to Southern and Jupiter how the calculation was done, and point out Southern’s high use of design and engineering resources and Jupiter’s high use of engineering resources relative to production machine hours. Roadster’s management should discuss ways of reducing the consumption of those resources, if possible, and show willingness to partner with them to do so. If the price rise is going to be steep, perhaps offer to phase in the new prices. 4. Other than for pricing, Roadster can also use the information from the department-based system to examine and streamline its own operations so that there is Diamond value-added from all indirect resources. It might set targets over time to reduce both the consumption of each indirect resource and the unit costs of the resources. The department-based system gives RC more opportunities for targeted cost management. 5. It would not be worthwhile to further refine the cost system into an ABC system if (1) a single activity accounts for a sizeable proportion of the department’s costs or (2) significant costs are incurred on different activities within a department, but each activity has the same cost driver or (3) there wasn’t much variation among contracts in the consumption of activities within a department. If, for example, most activities within the design department were, in fact, driven by CAD-design hours, then the more refined system would be more costly and no more accurate than the department-based cost system. Even if there was sufficient variation, considering the relative sizes of the three department cost pools, it may only be cost-effective to further analyse the engineering cost pool, which consumes about 79% ($220 000 $280 000) of the production overhead. The percentage of total driver units in each department used by the companies is: Cost Department Driver Design CAD-design hours Engineering Engineering hours Production Machine hours United Motors 28% 19 3 Holden Motors 51% 16 70 Nissan Vehicle 21% 65 27 The United Motors contract uses only 3% of total machines hours in 2013, yet uses 28% of CAD design-hours and 19% of engineering hours. The result is that the plant-wide rate, based on machine hours, will greatly underestimate the cost of resources used on the United Motors contract. This explains the 157% increase in indirect costs assigned to the United Motors contract when department rates are used. In contrast, the Holden Motors contract uses less of design (51%) and engineering (16%) than of machine-hours (70%). Hence, the use of department rates will report lower indirect costs for Holden Motors than does a plant-wide rate. Holden Motors was probably complaining under the use of the simple system because its contract was being overcosted relative to its consumption of MOH resources. United Motors, on the other hand was having its contract undercosted and underpriced by the simple system. Assuming that MP is an efficient and competitive supplier, if the new department-based rates are used to price contracts, United Motors will be unhappy. MP should explain to United Motors how the calculation was done, and point out United Motors’s high use of design and engineering resources relative to production machine hours. Discuss ways of reducing the consumption of those resources, if possible, and show willingness to partner with them to do so. If the price rise is going to be steep, perhaps offer to phase in the new prices. 4. Other than for pricing, MP can also use the information from the department-based system to examine and streamline its own operations so that there is maximum valueadded from all indirect resources. It might set targets over time to reduce both the consumption of each indirect resource and the unit costs of the resources. The department-based system gives MP more opportunities for targeted cost management. 5. It would not be worthwhile to further refine the cost system into an ABC system if there wasn’t much variation among contracts in the consumption of activities within a department. If, for example, most activities within the design department were, in fact, driven by CAD-design hours, then the more refined system would be more costly and no more accurate than the department-based cost system. Even if there was sufficient variation, considering the relative sizes of the 3 department cost pools, it may only be cost-effective to further analyse the engineering cost pool, which consumes 78% (A$240 000 A$308 600) of the manufacturing overhead. 19.21 Effect of different transfer-pricing methods on division operating profit (CMA, adapted) Sampson Ltd has two divisions. The Forming Division produces moulds, which are then transferred to the Finishing Division. The moulds are further processed by the Finishing Division and are sold to customers at a price of $300 per unit. The Forming Division is currently required by Sampson Ltd to transfer its total yearly output of 100 000 moulds to the Finishing Division at 120% of full manufacturing cost. Unlimited numbers of moulds can be purchased and sold on the outside market at $180 per unit. The following table gives the manufacturing cost per unit in the Forming and Finishing divisions for 2018: Direct materials cost Direct manufacturing labour cost Manufacturing overhead cost Total manufacturing cost per unit Forming Division $24 17 64a $105 Finishing Division $12 20 50b $82 a Manufacturing overhead costs in the Forming Division are 20% fixed and 80% variable. Manufacturing overhead costs in the Finishing Division are 65% fixed and 35% variable. b Required 1. Calculate the operating profits for the Forming and Finishing divisions for the 100 000 moulds transferred under the following transfer-pricing methods: (a) market price and (b) 120% of full manufacturing cost. 2. Suppose that Sampson Ltd rewards each division manager with a bonus, calculated as 2% of division operating profit (if positive). What is the amount of bonus that will be paid to each division manager under the transfer-pricing methods in requirement 1? Which transfer-pricing method will each division manager prefer to use? 3. What arguments would Scott Devon, manager of the Forming Division, make to support the transfer-pricing method that he prefers? Solution: (30 min.) Effect of different transfer-pricing methods on division operating profit (CMA, adapted) 1. Method A Method B Internal Internal Transfers at Transfers at Market Prices 120% of Full Costs Forming Division Revenues: $180, $126a × 100 000 units Costs: Division variable costs: $92.20b × 100 000 units Division fixed costs: $12.80c × 100 000 units Total division costs Division operating profit Finishing Division Revenues: $300 × 100 000 units Costs: Transferred-in costs: $180 $126 × 100 000 units Division variable costs: $18 000 000 $12 600 000 9 220 000 9 220 000 1 280 000 10 500 000 $7 500 000 1 280 000 10 500 000 $2 100 000 $30 000 000 $30 000 000 18 000 000 12 600 000 $49.50d × 100 000 units Division fixed costs: $32.50e × 100 000 units Total division costs Division operating profit 4 950 000 4 950 000 3 250 000 26 200 000 $3 800 000 3 250 000 20 800 000 $9 200 000 a $126 = Full manufacturing cost per unit in the Forming Division, $105 × 120% Variable cost per unit in Forming Division = Direct materials + Direct manufacturing labour + 80% of manufacturing overhead = $24 + $17 + (80% × $64) = $92.20 c Fixed cost per unit = 20% of manufacturing overhead = 20% × $64 = $12.80 d Variable cost per unit in Finishing Division = Direct materials + Direct manufacturing labour + 35% of manufacturing overhead = $12 + $20 + (35% × $50) = $49.50 e Fixed cost per unit in Finishing Division = 65% of manufacturing overhead = 65% × $50 = $32.50 b 2. Bonus paid to division managers at 2% of division operating profit will be as follows: Method A Internal Transfers at Market Prices Method B Internal Transfers at 120% of Full Costs Forming Division manager’s bonus (2% $7 500 000; 2% $2 100 000) $150 000 $42 000 Finishing Division manager’s bonus (2% $3 800 000; 2% $9 200 000) $76 000 $184 000 The Forming Division manager will prefer Method A (transfer at market prices) because this method gives $150 000 of bonus rather than $42 000 under Method B (transfers at 120% of full costs). The Finishing Division manager will prefer Method B because this method gives $184 000 of bonus rather than $76 000 under Method A. 3. Scott Devon, the manager of the Forming Division, will appeal to the existence of a competitive market to price transfers at market prices. Using market prices for transfers in these conditions leads to goal congruence. Division managers acting in their own best interests would state that they make decisions that are in the best interests of the company as a whole. Devon will further argue that setting transfer prices based on cost will cause to pay no attention to controlling costs since all costs incurred will be recovered from the Finishing Division at 120% of full costs.