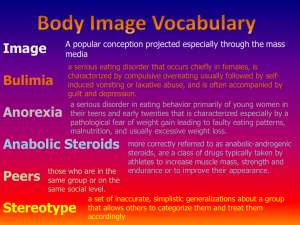

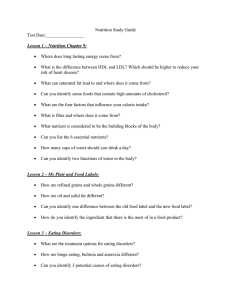

Eating disorders: a cbt approach Kanupriya Feeding and Eating disorders Feeding and Eating Disorders are characterized by a persistent disturbance of eating and eating related behaviour that results in the altered consumption or absorption of food and that significantly impairs physical health or psychological functioning. (APA-DSM 5, 2013) DSM 5 CLASSIFICATION ➔ PICA ➔ RUMINATION DISORDER ➔ AVOIDANT/RESTRICTIVE FOOD INTAKE DISORDER ➔ ANOREXIA NERVOSA ➔ BULIMIA NERVOSA ➔ BINGE EATING DISORDER ➔ OTHER SPECIFIED FEEDING OR EATING DISORDERS ➔ UNSPECIFIED FEEDING OR EATING DISORDERS Just one! Your own. (With a little help from your smart phone) ETIOLOGY “Genetics loads the gun and environment pulls the trigger.” Genetics Loads The Gun: Biology Personality Traits/Temperament And Environment Pulls The Trigger: Trauma/loss Family Dynamics Culture Pica DSM-V DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR EATING DISORDERS ● ● ● ● Persistent eating of nonnutritive, nonfood substances over the period of at least 1 month. The eating of nonnutritive, nonfood substances the inappropriate to the developmental level of the individual. The eating behaviour is not part of a culturally supported or socially normative practice. If the eating behaviour occurs in the context of another mental disorder (e.g. intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder) or medical condition (e.g. pregnancy), it is sufficiently severe to warrant additional clinical attention. Story for illustration purposes only Risk factors for eating disorders Psychological Risk Factors ● ● ● ● ● ● Perfectionism Anxiety Depression Difficulties regulating emotion Obsessive-compulsive behaviors Rigid thinking style (only one right way to do things, etc.) Biological Risk Factors • Having a close family member with an eating disorder • Family history of depression, anxiety, and/or addiction • Personal history of depression, anxiety, and/or addiction • Presence of food allergies that contribute to picky or restrictive eating (e.g. celiac disease) • Presence of Type 1 Diabetes Rumination Disorder ● ● ● ● Repeated regurgitation of food over the period of at least one month. Regurgitated food may be rechewed, re-swallowed, or spit out. Not attributable to an associated gastrointestinal or other medical condition (e.g. reflux). Does not occur exclusively during the course of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder, or avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. If symptoms occur in the context of another mental disorder (e.g. intellectual disability), they are sufficiently severe to warrant additional clinical attention. Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder A. A feeding or eating disturbance (e.g. lack of apparent interest in eating food; avoidance based on the sensory characteristics of food; concern about aversive consequences of eating)as manifested by persistent failure to meet appropriate nutritional and/or energy needs associated with one (or more) of the following: 1. Significant weight loss (or failure to achieve expected weight gain or faltering growth in children). 2. Significant nutritional deficiency. 3. Dependence on enteral feeding or oral nutritional supplements. 4. Marked interference with psychosocial functioning. ANOREXIA NERVOSA ● Restriction of energy intake relative to requirements, leading to a significantly low body weight in the context of age, sex, developmental trajectory, and physical health. Significantly low weight is defined as a weight that is less than minimally normal or, for children and adolescents, less than minimally expected. ● Intense fear of gaining weight or of becoming fat, or persistent behaviour that interferes with weight gain, even though at a significantly low weight. ● Disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self- evaluation, or persistent lack of recognition of the seriousness of the current low body weight. Anorexia nervosa: epidemiology Lifetime prevalence 0.5-1% Females:Males 10:1 Usually arises during adolescence or young adulthood Increased risk in 1st degree biological relatives with AN 1/3 will develop bulimia nervosa Long-term mortality 10-20% Medical Risks of Anorexia Nervosa Death (suicide, starvation, sudden cardiac death) Hypometabolic state (bradycardia, hypotension, hypothermia) Orthostasis Dehydration Arrhythmia, heart failure, liver failure Malnourishment Bone loss Lanugo Peripheral edema Stunted growth Delayed sexual maturity Hair loss, brittle hair Cognitive impairment Water intoxication On recovery: Re-feeding syndrome Bulimia Nervosa A. Recurrent episodes of binge eating. An episode of binge eating is characterized by both: 1. 2. ● ● ● ● Eating in a discrete period of time (e.g. within any 2 hour period), an amount of food that is definitely larger than what most individuals would eat in a similar period of time under similar circumstances; A sense of lack of control over eating during the episodes (e.g. a feeling that one cannot stop eating or control what or how much one is eating. Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain, such as self-induced vomiting; misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or other medications; fasting; or excessive exercise. The binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviors both occur, on average, at least once a week for 3 months. Self-evaluation is unduly influenced by body shape and weight. The disturbance does not occur exclusively during episodes of anorexia nervosa. Medical Risks of Bulimia Nervosa Electrolyte abnormalities Dental – loss of enamel, chipped teeth, cavities Parotid hypertrophy Conjunctival hemorrhages Calluses on dorsal side of hand Esophagitis, Mallory-weiss tears, Barrett esophagus hematemesis Laxative-dependent: cathartic colon, melena, rectal prolapse Poor nutrition (if severe purging) Binge-Eating Disorder ● ● Recurrent episodes of binge eating. An episode of binge eating is characterized by both: 1. Eating in a discrete period of time (e.g. within any 2 hour period), an amount of food that is definitely larger than what most individuals would eat in a similar period of time under similar circumstances; 2. A sense of lack of control over eating during the episodes (e.g. a feeling that one cannot stop eating or control what or how much one is eating). Binge eating episodes are associated with three or more of the following: 1. Eating much more rapidly than normal. 2. Eating until feeling uncomfortably full. 3. Eating large amounts of food when not feeling physically hungry. 4. Eating alone because of feeling embarrassed by how much one is eating. 5. Feeling disgusted with oneself, depressed, or very guilty afterwards. Types of assessments Bio-psycho-social Medical evaluation Psychiatric evaluation Nursing assessment Nutrition assessment Assessment and Diagnosis Initial Comprehensive History Includes: ● Eating disorder behaviors – current and past ● Substance abuse – current and past ● Treatment history – including medications ● Medical complications ● Social support ● Temperament ● Culture ● History of trauma and loss ● Family history of mental health, medical issues ● History of abuse, self injury, suicidality ● What patient views as causes - Often focuses on social as primary, intrapersonal distress secondary. Rarely recognize biological. Screening Tools for Assessment ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● Eating Disorder Questionnaire (EDQ) Obligatory Exercise Scale Addiction Severity Index (ASI) Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASR-v1.1) Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST) Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST) Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSS) Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) Mood Disorder Questionnaire URICA (readiness to change) FRIEL Co-dependency Inventory Multiscale Dissociation Inventory (MDI) Treatment: levels of care ● Outpatient – typically once a week therapy ● Intensive Outpatient (IOP) – 3-4 days/week, half-day ● Partial Hospitalization (PHP) of Day Treatment – 4-5 days/week, full-day ● Residential – 24/7 treatment, client does not go home ● Inpatient – 24/7 medical treatment to stabilize patient medically – usually short-term Treatment focus ● Medical/Nutrition Stabilization for medically compromised clients ● Weight restoration for underweight clients ● Neuronal plasticity – brain circuitry is modified by experience – CBT! ● Resolve trauma ● Develop new habits ● Grieve loss of ED ● Discover “Who Am I Without ED?” CBT for Eating Disorders Part I: Behavioral symptoms related to food and appearance Part II: Cognitive Symptoms related to eating disorders Part III: Relapse Prevention Case Carla is a 13 year-old Latina female who presented to the ER with a grand-mal seizure from hyponatremia. She had been binging on water in order to fend off hunger. She was 5 ft 4 inches and 90 pounds at presentation (her previous weight had been 160 lbs). She had stopped getting her period. Carla had always been a happy child and near-straight-A student, but had recently become obsessed with her schoolwork and isolated from her friends and close-knit family. She was also angry that her mother was pregnant. After acute medical stabilization, Carla reluctantly agreed to eat enough food to get to 105 lbs (BMI of 50%). She maintained this weight, as well as normal vital signs, for 6 months by eating the exact same thing every day: non-fat yogurt and non-fat cheese sandwiches. She remained depressed, suicidal, obsessive, isolative, cognitively slowed, and amenorrheic. She refused to believe that anorexia could kill her. Finally, Carla’s care was transferred to a multidisciplinary team. She started weekly Maudsley family therapy, and Prozac for depression. She gained 25 pounds in 2 months. She began menstuating only after she reached a BMI in the 75th percentile for her age/height. She now eats enchiladas, hamburgers, and pizza and hangs out with friends regularly. She still thinks she is fat, but is continuing family therapy to develop a sense of her own identity beyond food and body image. Establishing real time selfmonitoring The patient and therapist check the patient's weight once a week and plot it on an individualized weight graph. Patients are strongly encouraged not to weigh themselves at other times. Weekly in-session weighing has several purposes. First, it provides an opportunity for the therapist to educate patients about body weight and help patients to interpret the numbers on the scale, which otherwise they are prone to misinterpret. Second, it provides patients with accurate data about their weight at a time when their eating habits are changing. Third, and most importantly, it addresses the maintaining processes of excessive body weight checking or its avoidance COLLABORATIVE WEEKLY WEIGHING Patients should be helped to adhere to their regular eating plan and to resist eating between the planned meals and snacks. Two rather different strategies may be used to achieve the latter goals. The first involves helping patients to identify activities that are incompatible with eating and likely to distract them from the urge to binge eat (eg, taking a brisk walk) and strategies that make binge eating less likely (eg, leaving the kitchen). The second is to help patients to recognize that the urge to binge eat is a temporary phenomenon that can be “surfed.” Some “residual binges” are likely to persist, however, and these are addressed later. ESTABLISHING REGULAR EATING PATTERNS Addressing the over-evaluation of shape and weight Patients are helped to recognize that their multiple extreme and rigid dietary rules impair their quality of life and are a central feature of the eating disorder. A major goal of treatment is therefore to reduce, if not eliminate altogether, dieting. The first step in doing so is to identify the patient's various dietary rules together with the beliefs that underlie them. The patient is then helped to break these rules to test the beliefs in question and to learn that the feared consequences that maintain the dietary rule (typically weight gain or binge eating) are not an inevitable result. With patients who binge eat, it is important to pay particular attention to “food avoidance” (the avoidance of specific foods) as this is a major contributory factor. These patients need to systematically re-introduce the avoided food into their diet. Addressing Dietary Rules References Reinblatt, S.R. et.al. “Medication Management of Pediatric Eating Disorders” International Review of Psychiatry; April 2008 Yager, J. et.al. “Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Eating Disorders – Third Edition” from the American Psychiatric Association (APA) 2005 Silber, T. et.al. “Anorexia Nervosa Among Children and Adolescents” Advances in Pediatrics Vol 52, 2005 Locke, J. “Treatment Manual for Anorexia Nervosa”