Justice and Forgiveness: Retributive vs. Restorative

advertisement

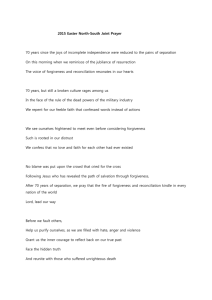

463 British Journal of Social Psychology (2014), 53, 463–483 © 2013 The British Psychological Society www.wileyonlinelibrary.com On the relationship between justice and forgiveness: Are all forms of justice made equal? Michael Wenzel1* and Tyler G. Okimoto2 1 2 Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia This research investigates whether, following a wrongdoing, the restoration of justice promotes forgiveness. Three studies – one correlational recall study and two experimental scenario studies – provide evidence that while a restored sense of justice is overall positively related to forgiveness, forgiveness is highly dependent on the means of justice restoration being retributive (punitive) versus restorative (consensus-seeking) in nature. The findings showed that, overall, restorative but not retributive responses led to greater forgiveness. Although both retributive and restorative responses appeared to increase forgiveness indirectly through increased feelings of justice, for retributive responses these effects were counteracted by direct effects on forgiveness. Moreover, the experimental evidence showed that, while feelings of justice derived from restorative responses were positively related to forgiveness, feelings of justice derived from retributive responses were not. Justice and forgiveness share a complex relationship. At the surface it would seem justice and forgiveness are antithetical to one another, where justice demands imposed offender suffering that seems counter to the undeserved benevolence implied by forgiving sentiments. Alternatively, justice and forgiveness can be thought of as independent from one another; victims may (or may not) forgive offenders irrespective of their punishment, or they may seek offender punishment regardless of their willingness to forgive. In fact, however, it is also possible that justice and forgiveness are not only compatible but rather functionally related. Forgiveness can help restore a sense of justice (Wenzel & Okimoto, 2010, 2012), and conversely, the restoration of justice can facilitate forgiveness (Tripp, Bies, & Aquino, 2007). Despite being a dominant assumption, this latter possibility, that the repair of a sense of justice facilitates forgiveness, has received surprisingly little attention in psychological research and is the focus of this article: Are victims more willing to forgive when measures have been taken to restore their sense of justice? Justice and forgiveness Justice is defined as a subjective sense of restored moral order and moral rightness of response following a transgression or wrongdoing. What justice means is subjective, but to the extent that people feel an offender deserves to be punished – a deeply ingrained *Correspondence should be addressed to Michael Wenzel, School of Psychology, Flinders University, GPO Box 2100, Adelaide, SA 5001, Australia (e-mail: michael.wenzel@flinders.edu.au). DOI:10.1111/bjso.12040 464 Michael Wenzel and Tyler G. Okimoto notion of justice in Western societies (Hogan & Emler, 1981) – justice would seem antithetical to forgiveness. Forgiveness has been defined as the transformation of a victim’s motives and attitudes towards the offender from negative to positive, indicated by reduced revenge or retributive tendencies, reduced avoidance and increased benevolence towards the offender (McCullough, Root, & Cohen, 2006; McCullough et al., 1998). It has been likened to altruistic behaviour that is most proximally driven by empathy for the offender (McCullough, Worthington, & Rachal, 1997; McCullough et al., 1998): A benevolent act despite the forgiver’s ‘moral right, and perhaps even … moral obligation, to seek retribution by punishing or harming the offender’ (Aquino, Grover, Goldman, & Folger, 2003, p. 212). As an act of mercy, forgiveness would seem to sacrifice justice, abandon justice standards and, therefore, be in opposition to justice (Exline & Baumeister, 2000). However, research suggests that justice and forgiveness are actually quite compatible. For example, Karremans and Van Lange (2005) found that participants primed with the concept of justice showed greater, not less, propensity to forgive. While there is little empirical research on this question, there are dominant theoretical views that argue that justice restoration may in fact benefit forgiveness. Tying in with the idea that forgiveness implies some sacrificing of justice, it has been argued that such a sacrifice would be easier if it is small rather than large. If the initial injustice the offender caused is more benign, and/or actions have been taken to reduce the injustice and restore justice, then victims should find it easier and be more willing to forgive. This idea has been articulated in the concept of the injustice gap (Exline, Worthington, Hill, & McCullough, 2003; Worthington, 2006). After a transgression, the injustice gap is the discrepancy between the victims’ entitlements or desired just treatment and their actual treatment, hurt and victimization. However, the discrepancy may be subsequently reduced by the offenders being punished or offering an apology, and/or the victims being compensated, given the opportunity to express their hurt in a victim statement, and so on. Failing these responses, the discrepancy between the victims’ actual outcome and what they desire as a just outcome may remain undiminished (or may even increase), causing victim dissatisfaction and an unwillingness to forgive (Worthington, 2006). In this sense, forgiveness is positively dependent on the restoration of justice. Even if the discrepancy is often not completely reversible (not least because the offender’s actions cannot be erased) and forgiveness is needed to bridge the remaining gap, this ‘sacrifice’ is easier if the gap has been narrowed. Importantly, the injustice gap concept implies that ‘any factor that influences perceived injustice should thus influence a person’s ability or willingness to forgive’ (Exline et al., 2003, p. 344). So, any intervention (e.g., third-party punishment), action (e.g., offender apology), or cognitive rationalization (e.g., external attribution) that increases feelings of justice in the victim should therefore increase the probability that the victim will forgive the offender. A similar proposition is made in Tripp, Bies, and Aquino’s (2007) vigilante model of justice, which also predicts that any given justice response will increase the likelihood of forgiveness by restoring a sense of justice and reducing negative emotions. Specifically, they argue that both apologies and third-party punishment can increase forgiveness through the restoration of justice, and even proportionate revenge by the victim may lead to forgiving tendencies. As far as we know neither the injustice gap notion nor the vigilante model have been put to a proper empirical test. Certainly, existing research has shown that perceptions of severity and attributions of blame to the offender are negatively related to forgiveness (Boon & Sulsky, 1997; Fehr, Gelfand, & Nag, 2010), ostensibly because they represent a Justice and forgiveness 465 larger injustice gap. Likewise, conciliatory behaviour such as apologies have been found to promote forgiveness (e.g., Fehr et al., 2010; McCullough et al., 1998), ostensibly because they narrow the injustice gap. However, we are not aware of any research showing that retribution (by third parties or the victims) facilitates forgiveness. In this research we critically test this idea. However, we question the validity of the proposition that justice restoration by any means promotes forgiveness. We argue that the concept of the ‘injustice gap’ presupposes a unitary understanding of justice, but that when it comes to forgiveness, not all forms of justice are made equal. Although some injustice responses do indeed increase feelings of justice and lead to forgiveness, other responses can increase feelings of justice without impacting a victim’s willingness to forgive. Retributive versus restorative justice Recent theoretical advances in the psychology of injustice and victimization have suggested a more nuanced understanding of what it means to restore justice. Justice restoration theory (Wenzel, Okimoto, Feather, & Platow, 2008) proposes that there are two distinct understandings of what justice means to victims and what its restoration entails: a retributive versus restorative understanding of justice. A retributive notion conceptualizes justice as unilateral assertion against the offender. On the other hand, a restorative notion conceptualizes justice as achieving a renewed consensus between the affected parties. These two understandings of justice are conceptually distinct, yet not necessarily mutually exclusive (Okimoto, Wenzel, & Feather, 2012). While initially conceptualized as a way to identify preferences for punitive sentencing versus restorative conferencing in legal domains, this theory serves as a comprehensive model for understanding all types of injustice responses (Okimoto & Wenzel, 2008) as they can entail essentially retributive (e.g., punishment, revenge) or essentially restorative (e.g., apologies, dialogue) justice meanings. This analysis is based on evidence that retributive and restorative responses primarily address different underlying justice goals (e.g., Okimoto et al., 2012; Wenzel, Okimoto, Feather, & Platow, 2010). Retributive responses achieve justice through unilateral assertion against the offender, thus addressing concerns over the victims’ status and power usurped by the offender. In contrast, restorative responses achieve justice through a renewed understanding between victim and offender, thus addressing concerns over the violation of shared norms and values that define the victim-offender relationship or common group identity. By analysing various responses according to the fundamental psychological needs they address, justice restoration theory (Wenzel et al., 2008) helps to specify when different responses are deemed appropriate and why – predictions that extend to interpersonal, intragroup, and intergroup phenomena, and to social, legal, and organizational contexts (Okimoto, Wenzel, & Platow, 2010). This theoretical approach has implications for our understanding of forgiveness as it relates to justice. It suggests specific circumstances in which the injustice gap prediction that justice restoration will increase forgiveness may not hold true. Specifically, this approach suggests that the positive link between justice and forgiveness might only hold for restorative, not retributive, means of justice restoration. First, we contend retributive responses, while restoring justice, are otherwise incompatible with forgiveness. That is, in addition to their justice-restoring effect (and its presumed benefit for forgiveness), retributive responses have psychological implications that tend to make people less willing to forgive. Retributive responses operate by 466 Michael Wenzel and Tyler G. Okimoto reassertion against offenders, lowering their status and power and symbolically excluding them; they label offenders as deviants who do not share the moral values constitutive of one’s identity (Okimoto & Wenzel, 2009). Retributive responses create social distance, reducing the basis for empathy and shared identity that have been shown to facilitate forgiveness (McCullough et al., 1997; Wohl & Branscombe, 2005). Thus, while retributive responses might increase forgiveness indirectly through the restoration of justice, their direct effect runs counter to this and may neutralize the indirect benefits. In contrast, restorative responses operate by seeking consensus and reaffirming values that define a shared identity (Wenzel et al., 2008). Thus, restorative responses not only increase forgiveness indirectly through perceptions of justice but their psychological implications of inclusion of the offender, and the trust and hope that the offender shares the same moral values, may also be directly related to forgiveness – indirect and direct processes that add to another: Hypothesis 1: Restorative responses will have both a positive direct and indirect effect (via justice) on forgiveness, both adding to a positive total effect on forgiveness. Retributive responses will have a positive indirect effect on forgiveness (via justice), but a negative direct effect; the combined total effect may not be significant (depending on the relative strength of the two effects). Second, we contend that while retributive responses lead to feelings of justice, the quality of this justice may be different from the justice achieved through restorative means. Even though both retributive and restorative responses may lead participants to report greater feelings of justice, the essence of this justice differs. Retributive responses achieve retribution-oriented justice through the imposition of punishment against the offender, implying a re-balancing of the scales (in status or power) for one party relative to the other (Wenzel et al., 2008). The very understanding of retributive justice suggests oppositional identities and a negative interdependence over status/power that is not conducive to forgiveness. In contrast, justice derived from restorative means has a different quality; it is restorative justice achieved through social reaffirmation of the values violated by the offence (Wenzel et al., 2008). It implies a positive interdependence regarding the social validation of values and a shared identity that are conducive to forgiveness. In other words, the relationship between feelings on justice and forgiveness will depend on the means from which those justice feelings are derived because the different means establish a different quality of justice; the means will therefore moderate the relationship between justice and forgiveness. Hypothesis 2: Feelings of justice will generally be positively related to forgiveness, but this will be qualified by the nature of the response from which those feelings derive: feelings of justice achieved through a restorative response (compared to an unspecified control) will be more strongly related to forgiveness; feelings of justice achieved through a retributive response (compared to an unspecified control) will be less strongly related to forgiveness. The predictions are in line with findings that forgiveness is consistent with a restorative understanding of justice but in fact inconsistent with a retributive understanding (Okimoto et al., 2012; Strelan, Feather, & McKee, 2008, 2011). However, previous research established these relationships in self-reported preferences for justice type and forgiveness, and thus it is not surprising that retributive justice orientations (Okimoto et al., 2012) or retributive goals (Strelan et al., 2011) are related to a tendency to seek Justice and forgiveness 467 revenge, which is a definitional counter-indication of forgiveness (McCullough et al., 1997). However, this prior work does not speak to the consequences for forgiveness when retributive or restorative responses are used to restore justice, or whether the restoration of justice is indeed beneficial for the willingness to forgive. Taken together, both theoretical predictions suggest that the link between justice and forgiveness should be qualified by the nature of the justice-restoring response, with retributive responses being less conducive to forgiveness than restorative responses. However, the two predictions differ in the process through which that provision occurs. The difference is in whether the qualification comes from the retributive intervention itself having negative effects on forgiveness independent of its beneficial indirect effect through justice (i.e., suppression), or from the essence of the achieved justice being different depending on the nature of the intervention (moderated mediation). Both processes may also operate in tandem. STUDY 1 Study 1 used a recall paradigm. Participants were asked to recall a situation where they felt they were the victim of a transgression. To explore whether results would be the same irrespective of seriousness, they were asked to recall either a serious or a less serious transgression. They then indicated retrospectively on a number of self-report scales what was done in response, the degree to which they felt justice was restored, and their level of forgiveness to the offender. Method Participants and design A total of 105 Australian university students participated in the study (69% female students, age M = 24.5, SD = 7.65). They were randomly allocated to one of two conditions, asking them to recall a transgression of low versus high seriousness. Materials and procedure Participants were asked to ‘Think about a time when you were the victim of what you consider to be a (minor, serious) transgression – some type of crime, offence, or unfair treatment that happened to you that you felt was (not very) serious.’ They rated the seriousness of the recalled transgression on three items (e.g., ‘How serious was this incident?’; a = .87). Next, participants were asked to ‘really try and reflect back about the situation’ and were prompted to write down their recollections in an open text-field. They then completed the main dependent variables. Responses from multi-item measures were averaged to obtain scale scores. Retributive response Retributive justice refers to justice through imposition of punishment (Wenzel et al., 2010). Seven items assessed whether participants believed there was a retributive response to the transgression, whether the offender was punished and received their just desert (e.g., ‘How severely was the offender punished, compared to similar incidents of this type?’, 1 = much less than usual, 7 = much more than usual; ‘Did the offender get 468 Michael Wenzel and Tyler G. Okimoto what was deserved – his/her just deserts?’, ‘Were you able to pay the offender back?’, 1 = not at all, 7 = very much; a = .91). Note that some of the items assumed that the participant knew what happened to the offender; when missing values resulted from these items, scores were the average of the available responses.1 Restorative response Restorative justice refers to justice through seeking consensus between the parties, about wrongdoing, the values violated, and what can be done to repair the harm (Wenzel et al., 2010). Seven items assessed whether participants believed there was a restorative response, whether the participants and the offender worked towards a shared understanding of the wrongdoing and what needed to be done (e.g., ‘Did you try to communicate to the offender that what he/she did was wrong?’, ‘Did the offender seem to acknowledge that the values he/she violated were indeed important?’, ‘Did you and the offender agree about how the situation should be resolved?’, 1 = not at all, 7 = very much; a = .91). Retributive and restorative response scales were strongly correlated, r = .70. Given the high correlation between the measures of retributive and restorative response, we investigated further whether the empirical evidence supported their conceptual distinction. First, a principal component analysis with varimax rotation extracting two factors explained 64% of variance in total (34% and 30% by the two factors, respectively); all items loaded on their designated factor with loadings >.61 (there were some cross-loadings, but these were consistently smaller or insubstantial). Second, we conducted confirmatory factor analyses and compared a 1-factor model with the theoretically assumed 2-factor model. A chi-square difference test showed a significantly better fit of the 2-factor compared to 1-factor model, Dv2(1) = 57.31, p < .001. Justice Eight items assessed feelings of justice (e.g., ‘Do you feel the situation, as it unfolded, is very unjust? [reverse-coded]’, ‘Given everything that has happened, is your sense of fairness satisfied?’, 1 = not at all, 7 = very much; a = .89). Forgiveness Eight items assessed participants’ sentiments of forgiveness and willingness to forgive (e.g., ‘Do you hold a grudge against the offender? [reverse-coded], ‘Do you wish that something bad would happen to the offender’ [reverse-coded], ‘Do you want to see the offender hurt and miserable?’ [reverse-coded], ‘Do you feel goodwill for the offender?’, ‘Do you trust the offender?’, ‘Do you (or would you) find it difficult to act warmly towards the offender?’, ‘Do you harbour negative feelings towards the offender?’ [reverse-coded], ‘If you had the opportunity now, would you be willing to express your forgiveness to the offender?’; 1 = not at all, 7 = very much; a = .86). 1 It was natural that, due to circumstances, some participants did not know what other actions had been taken against the offender; however, this did not diminish the validity of their responses about their own involvement in punishment. In order not to lose valuable information, introduce bias in the selection of cases, and diminish statistical power, we retained all participants with the information they could provide. Note that the pattern of results was the same when respondents with missing values on any of the items were excluded from the analyses. Justice and forgiveness 469 Results Participants recalled a great variety of situations in private, workplace and community contexts, including disrespect, procedural unfairness, sabotage of one’s work, theft and major fraud. As intended, the events recalled were less serious in the low (M = 4.45, SD = 1.45) compared to the high seriousness condition (M = 5.07, SD = 1.55), t(103) = 2.14, p = .034; however, in both conditions the perceived seriousness was rated above the midpoint of the scale, t(49) = 2.18, p = .034 and t(54) = 5.26, p < .001 respectively. Analysis also indicated that seriousness did not moderate any of the findings reported below; interactions involving seriousness were therefore omitted from the reported analyses. Zero-order correlations showed that forgiveness was positively correlated with justice (r = .54), retributive response (r = .27), and restorative response (r = .46); justice was positively correlated with retributive response (r = .43) and restorative response (r = .42); and retributive and restorative responses were positively correlated (r = .70). We used multiple regression techniques to test our predictions (see Table 1). First, we tested for the effects of retributive and restorative responses on feelings of justice. Controlling for manipulated seriousness, which had a negative effect on feelings of justice, both retributive and restorative responses were positively related to justice perceptions. Second, we conducted a hierarchical regression for forgiveness, including seriousness as well as retributive and restorative responses in the first step, adding perceptions of justice as a predictor and suspected mediator in a second step, and the two-way interactions between perceived justice and retributive and restorative responses (all centred) in the third step. Diagnostics indicated no problems of multicollinearity at any of these steps (Tolerance >.46, Condition Index = 3.20). In Step 1, seriousness had a negative effect on forgiveness; retributive response had no significant effect, while restorative response was positively related to forgiveness. In Step 2, justice perceptions were positively related to forgiveness; when including justice, the effect of the restorative response was reduced, but still significant and positive, while the retributive response now had a significantly negative effect on forgiveness. These results were not further qualified by any interaction effects in Step 3. Bootstrapping techniques for testing specific indirect effects with small samples (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) showed that restorative response had a significant positive indirect effect on forgiveness through feelings of justice, B = .09, SE = .05 (95% CI = 0.01–0.21). The indirect effect of retributive response was also significant, B = .11, SE = .06 (95% CI = 0.003–0.25). However, because its direct effect was in the opposite, negative direction, the total effect of the retributive response in Step 1 was not significant. Discussion Study 1 showed that restorative, but not retributive, responses appeared to increase forgiveness, supporting Hypothesis 1. While both seemed to increase feelings of justice, and justice was positively related to forgiveness, this only translated into a total effect on forgiveness for restorative responses; for retributive responses, the positive indirect effect on forgiveness was counteracted by a negative direct effect. In line with the concept of an injustice gap, reduction in injustice feelings appears to increase forgiveness. However, only restorative responses helped to restore justice and foster forgiveness. Notably, Study 1 did not show support for Hypothesis 2; the type of justice intervention did not appear to moderate the link between justice and forgiveness. This Seriousness Retributive response Restorative response Seriousness Retributive response Restorative response Justice Retributive 9 Justice Restorative 9 Justice Justice .26 .26 .20 .31 .13 .45 B .11 .13 .10 .12 .13 .10 – – – SE B B SE B .20 .25 .26 .23 .12 .55 – – – 2.33* 2.06* 2.11* 2.67* .99 4.57*** .19 .24 .37 .44 N/A .11 .12 .09 .09 .14 .22 .45 .42 – – b t-value b 1.76† 2.00* 3.95*** 4.63*** – – t-value .21 .22 .37 .43 .05 .00 N/A B .11 .12 .09 .10 .08 .07 SE B .16 .20 .45 .41 .07 .00 b STEP 3 1.88† 1.77† 3.97*** 4.48*** .65 .04 t-value Note. For Justice as dependent variable (D.V.), R2 = .26, F(3, 101) = 11.51; for Forgiveness, in Step 1: R2 = .26, F(3, 101) = 11.94; in Step 2: R2 = .39, F(4, 100) = 16.12; in Step 3: R2 = .40, F(6, 98) = 10.72. † p < .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. Forgiveness Predictor D.V. STEP 2 STEP 1 Table 1. Hierarchical regression results for dependent measures (Study 1) 470 Michael Wenzel and Tyler G. Okimoto Justice and forgiveness 471 finding may reflect actual relationships, however, it could also be an artefact of the correlational design of the study. The presumed measured moderators – retributive and restorative response – were not designed to be mutually exclusive and were indeed strongly correlated, limiting their distinctive variance and capacity to differentially moderate the effects of justice. Generally, it has been argued that moderation effects are more difficult to detect in correlational studies (McClelland & Judd, 1993), which is why we employed experimental designs next. STUDY 2 By drawing on participants’ real-life experiences, Study 1 benefits from high ecological validity, but it is limited in internal validity. The correlational data do not permit causal inferences. Therefore, in Study 2 we offer a complimentary experimental test of the same predictions, this time using a scenario methodology that allows for causal interpretations. Method Participants and design Participants were 140 Australian university students (66% female students, age M = 24.2, SD = 7.62). They were randomly allocated to a 3-cell experimental design: retributive response, restorative response, or inaction (control). Materials Participants completed a paper/pencil questionnaire. They were asked to imagine that another student, Sarah, had stolen their study notes days before the examination, and that University Student Services handled their formal complaint. The scenarios varied in whether the complaint was resolved through retributive or restorative processes (based on theoretical conceptualizations and experimental manipulations used by Wenzel et al., 2010), versus inaction. The student services administrator called in both students for a meeting. In the retributive response condition the administrator unilaterally imposed a punishment on the offender: [He] tells the two of you that, after carefully weighing the implications of the offence and how it has affected you, he has made an objective decision about what he believes to be appropriate punishment. He also explains to Sarah that she had no choice in the matter but to accept her punishment. In the restorative response condition, offender and victim engaged in a dialogue to come to a shared understanding and bilateral solution: [He] encourages both you and Sarah to engage in a discussion about the incident. Both of you express your feelings and views about the situation. Eventually, you both come to an agreement about appropriate student conduct. You seem to reach a shared understanding about the implications of the offence and how it has affected you, and you also reach an agreement about Sarah’s punishment. The punishment was the same in both conditions (an unpaid service to the university). In contrast, in the control condition participants were told they received an email from student services saying that ‘because there is no proof, nothing can be done about the situation.’ 472 Michael Wenzel and Tyler G. Okimoto Seriousness Prior to the experimental manipulation, participants rated the seriousness of the incident on two items: ‘What happened in this situation was really no big deal’ (reverse-coded), and ‘What happened in this situation was very serious’ (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The two items were highly correlated (r = .72) and responses were averaged. Justice We used seven items to measure feelings of justice similar to Study 1 (a = .91). Forgiveness We measured forgiveness with the 18-item Transgression-Related Interpersonal Motivations Scale (TRIM-18; McCullough et al., 2006). It taps into three aspects of forgiveness: lack of revenge (e.g., ‘Somehow, I’ll make Sarah pay’, reverse-coded), lack of avoidance (e.g., ‘I will try to keep as much distance between us as possible’, reverse-coded) and benevolence (e.g., ‘Even though Sarah’s actions hurt me, I have goodwill for her’; 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Analyses indicated no notable differences among the three aspects of forgiveness, so for parsimony all 18 items were averaged into a single forgiveness score (a = .88). Results The level of seriousness attributed to the offence did not differ among the three experimental conditions, F(2, 137) = .21, p = .814. Overall, the participants rated the transgression as very serious (M = 6.05, SD = 1.12) and clearly different from the scale mid-point, t(139) = 21.67, p < .001. Forgiveness and justice were positively correlated at r = .38. We again used multiple regression techniques to test our predictions (see Table 2 and Figure 1). We created two dummy-coded variables to represent the retributive and restorative response conditions, treating the control condition as the reference group. Diagnostics indicated no problems of multicollinearity at any of the following steps (Tolerance >.11, Condition Index = 8.11). First, we tested for the effects of retributive and restorative responses on feelings of justice. Both retributive and restorative responses had a significant positive effect on justice perceptions. Second, we conducted a hierarchical regression for forgiveness, including retributive and restorative responses in the first step, and adding perceptions of justice as a predictor in a second step. In Step 1, a retributive response had no significant effect, while a restorative response had a significant positive effect on forgiveness. In Step 2, justice perceptions were significantly positively related to forgiveness; when controlling for the mediating effect of justice, the positive effect of the restorative response was no longer significant, and a marginally significant negative effect of retributive response was revealed. Bootstrapping techniques for testing specific indirect effects with small samples (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) showed that the restorative response had a significant indirect effect on forgiveness through feelings of justice, B = .57, SE = .18 (95% CI = 0.25–0.97). There was likewise a significant indirect effect for the retributive response, B = .43, SE = .12 (95% CI = 0.22– 0.71). Importantly, similar to Study 1, the indirect effect for the restorative response translated into (or partially accounted for) a significant total effect, whereas the significant indirect effect of retributive justice was counteracted by a (marginal) negative direct effect Retributive response Restorative response Retributive response Restorative response Justice Retributive 9 Justice Restorative 9 Justice Justice 1.71 2.23 .01 .83 B .25 .25 .21 .21 B SE B .52 .69 .01 .36 – – – 6.87*** 9.00*** .07 3.94*** – – – .42 .26 .26 N/A .23 .25 .07 .18 .11 .36 – – b t-value b SE B 1.80† 1.03 3.67*** – – t-value .64 .06 .48 .40 .19 N/A B .29 .30 .16 .20 .19 SE B .28 .03 .68 .27 .17 b STEP 3 2.22* .20 3.05** 2.02* 1.03 t-value Note. For Justice as dependent variable (D.V.), R2 = .39, F(2, 137) = 44.50; for Forgiveness, in Step 1: R2 = .13, F(2, 137) = 10.06; in Step 2: R2 = .21, F(3, 136) = 11.82; in Step 3: R2 = .23, F(5, 134) = 8.07. † p < .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. Forgiveness Predictor D.V. STEP 2 STEP 1 Table 2. Hierarchical regression results for dependent measures (Study 2) Justice and forgiveness 473 474 Michael Wenzel and Tyler G. Okimoto Retributive Response –.28* (.01) Forgiveness ** –.03 (.36 ) Restorative Response *** .69 Control = .68** Retributive response = .12 Restorative response = .41** .52*** Feelings of Justice Figure 1. Study 2. Direct and indirect effects of justice response on forgiveness (total effects in parentheses). of the retributive response that resulted in a non-significant total effect of retributive justice. In a final, third step of the hierarchical regression we added the two-way interactions between perceived justice and the two experimental conditions. The Justice 9 Retributive response interaction was significant, whereas the Justice 9 Restorative response interaction was not (see Table 2, right-hand column). Probing the significant interaction effect showed that the simple effect of justice was significant and positive in the control condition, b = .68, p = .003, and the restorative response condition, b = .41, p = .005, but not significant in the retributive response condition, b = .12, p = .489. Thus, while perceptions of justice were overall positively related to forgiveness, this was in fact only true in the control and restorative response conditions, but not when the response was retributive. Given the significant moderation of the justice-forgiveness link, we next investigated its implications for the mediation effects, using an integrated analytical approach that combines tests for moderation and mediation effects. We used the PROCESS macro by Hayes (2012; Model 74) to test the model where an independent variable moderates the relationship between mediator and outcome variable and, thus, moderates its own indirect effect (see Model 1 in Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, 2007). The results for the complete model were identical with those reported in Step 3 above (see Table 2). Furthermore, the analysis provided bootstrap tests of the conditional indirect effects that illustrate the moderated mediation: The indirect effect of retributive response (under the condition of a retributive response being administered) was in fact not significant, B = .14, SE = .25 (95% CI = 0.37–0.58).2 In contrast, the conditional indirect effect of restorative response via perceived justice on forgiveness was significant, B = .64, SE = .22 (95% CI = 0.28–1.15). Discussion Study 2 replicated the basic findings of Study 1, allowing for a causal interpretation of the relationships. A restorative response led to greater forgiveness, mediated by perceptions of justice. A retributive response also led to greater justice and thus indirectly to greater forgiveness, but this appeared to be counteracted by a negative direct effect on forgiveness. However, the experimental design of Study 2 also permitted a test of the 2 The effect of retributive response was only significant under the moderating condition that no such response was administered, which is of course paradoxical and not meaningful, B = .82, SE = .27 (95% CI = 0.33–0.39). The interpretational difficulty of the moderated indirect effects is a peculiarity of the case where dichotomous variables act as independent variable and moderator at the same time. In this situation, only one of the conditional indirect effects is meaningful (A. F. Hayes, personal communication, 7 February 2013). Justice and forgiveness 475 possibility that subjective feelings of justice do not necessarily mean the same thing when participants arrive at these through different responses. Specifically, justice perceptions derived from restorative responses (as well as, here, inaction) appear to facilitate forgiveness, while justice perceptions deriving from retributive responses do not. As a consequence, only restorative, but not retributive, responses indirectly facilitated forgiveness via the restoration of a sense of justice. STUDY 3 In Studies 1 and 2, we operationalized restorative justice as the seeking and achieving of a shared consensus about the wrongdoing and its consequences. While true to its theoretical conceptualization (Wenzel et al., 2008), such consensus-building may involve complex processes that make it quite different from a single act such as punishment. In Study 3, we therefore focused instead on a single restorative act that has the potential to contribute to consensus: an apology. While a full apology may contain a greater number of elements, such as an expression of concern for the victim, or the offer of repair (e.g., Goffman, 1967; Scher & Darley, 1997; Schlenker & Darby, 1981), at the core of an apology is an acknowledgement of wrongdoing and expression of remorse (Lazare, 2004), which is also how it was operationalized in this study. An apology signals an endorsement of the victim’s moral position, promoting a consensus constitutive of restorative justice (Okimoto et al., 2008); indeed, research has shown that a victim’s desire for an apology is correlated with a restorative understanding of justice (Okimoto et al., 2012). As we argued earlier, restorative responses facilitate forgiveness through feelings of justice, partly explaining why apologies tend to elicit forgiveness in victims (e.g., Darby & Schlenker, 1989; McCullough et al., 1997). The focus on apology also allows us to further distinguish between two possible forms of restoration. On the one hand, an apology may contribute to a consensus between victim and offender, which presumably communicates that the offender reaffirms and is committed to the violated values, repairing the identity between these two parties and motivating victims to forgive. On the other hand, an apology that is issued by a third party, such as representatives of the group to which offender and victim belong, may also socially validate the violated values; by siding with the victim, the group might be seen to reaffirm the values and thus alleviate the victim’s concerns (see also Eaton, Struthers, & Santelli, 2006). However, a third-party apology does not imply a consensus with the offender; in fact, it might indicate a distancing of the group from the offender. Stated simply, consensus can be achieved while being either inclusive or exclusive of the offender (Okimoto & Wenzel, 2009), and it is an empirical question whether or not it is a specific type of consensus that motivates forgiveness. Hence, in Study 3 we included a third-party apology and an offender apology to distinguish the social validation of values with and without offender consensus. Method Participants and design Participants were 314 U.S. residents who took part in an online study (64% female participants, age M = 35.6, SD = 11.81). They were randomly allocated to a four-cell experimental design: retributive response, third-party apology, offender apology, or inaction (control). 476 Michael Wenzel and Tyler G. Okimoto Materials Participants were asked to imagine they were an employee in a large advertising agency and that another employee, Jason, falsely claimed credit for a successful marketing campaign that, participants were told, was actually theirs. The supervisor quickly understood that Jason blatantly lied. The company did not want to fire him, but put an incident report in his employee record. In the control condition, there was no further action beyond this report. In addition, in the retributive response condition, Jason ‘was assigned to the least popular project at the company’ and ‘was also put on ‘probation’ in the company’ having to undergo a disciplinary review in 6 months’ time to get off probation. Alternatively, in the third-party apology condition, ‘your supervisor made a point to call you into his office and personally apologize for what happened in the situation’, saying, ‘I’m actually really embarrassed about the fact that Jason almost got away with his lie. I am sincerely sorry about what happened – the whole management team is’. Finally, in the offender-apology condition, ‘Jason (the offender) made a point to call you into his office and personally apologize for what happened in the situation’, saying, ‘I’m actually really embarrassed about the fact that I tried to get away with lying. I am sincerely sorry about what happened’. Seriousness Prior to the experimental conditions (i.e., the different resolutions of the situation), participants rated the seriousness of the incident on a single item: ‘How serious was this incident?’ (1 = not at all serious, 7 = extremely serious). Justice Six items measured feelings of justice and satisfaction with the resolution (e.g., ‘I am very satisfied with the situation as it now stands’, ‘My sense of fairness has been satisfied’; 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The item responses were averaged to obtain scale scores (a = .92). Forgiveness We measured forgiveness with nine items that tapped into lack of revenge (five items based on TRIM-18; McCullough et al., 2006; e.g., ‘I’m going to get even’, reverse-coded) and express forgiveness (four items based on Okimoto et al., 2012; ‘I forgive the offender for what he did to me’, ‘I would offer my willingness to forgive the offender’, ‘I want to explain to the offender that I wish to settle the incident and move on’, and ‘I would want the offender to know that if the harm can be repaired, it can be forgiven’); items were averaged into a single score (a = .84). Results The level of seriousness attributed to the offence did not differ among the three experimental conditions, F(3, 311) = .30, p = .828. Overall, the participants rated the transgression as very serious (M = 6.18, SD = 0.96) and clearly different from the scale mid-point, t(314) = 40.51, p < .001. Forgiveness and justice were positively correlated at r = .34. Justice and forgiveness 477 We used multiple regression techniques to test our predictions (see Table 3 and Figure 2). We dummy-coded the experimental conditions and treated the control condition as reference group. Diagnostics indicated no problems of multicollinearity at any of the following steps (Tolerance >.34, Condition Index = 4.12). First, we tested for the effects of retributive response, third-party apology and offender apology on feelings of justice. All three led to greater feelings of justice compared to the control condition. Second, we conducted a hierarchical regression for forgiveness, including retributive response, third-party apology and offender apology in the first step, and adding perceptions of justice as a predictor in a second step. In Step 1, a retributive response and third-party apology showed no significant effect, while an offender apology had a significant positive effect on forgiveness. In Step 2, justice perceptions were significantly positively related to forgiveness; and when including justice the positive effect of restorative justice was diminished (although still significant), while the effects for retributive response and third-party apology were still non-significant, although now with a negative sign. Bootstrapping techniques for testing specific indirect effects (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) showed that the restorative response had a significant positive indirect effect on forgiveness through feelings of justice, B = .16, SE = .07 (95% CI = 0.04–0.30). There was likewise a significant positive indirect effect for the retributive response, B = .18, SE = .07 (95% CI = 0.06–0.37) and for third-party apology, B = .23, SE = .07 (95% CI = 0.12–0.39). Similar to Studies 1 and 2, however, the indirect effect for the restorative response translated into (or partially accounted for) a significant total effect, whereas this was not the case for retributive justice or third-party apology. Finally, in Step 3 of the hierarchical regression, we added the two-way interactions between perceived justice and the three experimental conditions (see Table 2, right-hand column). The Justice 9 Retributive response interaction was not significant, although the apparent negative trend was consistent with Study 2. In contrast, the Justice 9 Thirdparty apology interaction was marginally significant and positive, and the Justice 9 Offender apology interaction was significant and positive. Probing these interaction effects (see Figure 2) showed that the simple effect of justice was positive and the strongest in the offender apology condition, b = .70, p < .001, and similarly strongly positive in the third-party apology condition, b = .49, p < .001; both were, as implied by the interaction effects, stronger than in the control condition, b = .26, p = .003, while the relationship between justice and forgiveness was not significant in the retributive response condition, b = .06, p = .574. We used again Hayes’s (2012) PROCESS macro (Model 74) for a combined analysis of moderation and mediation. The results for the complete model were identical with those reported in Step 3 above (see Table 3). Bootstrap tests of the conditional indirect effects showed that, taking the moderated nature of the link between justice and forgiveness into account, the indirect effect of offender apology was indeed significant, B = .32, SE = .14 (95% CI = 0.08–0.63). Similarly, the indirect effect of group apology was significant, B = .33, SE = .11 (95% CI = 0.15–0.58). In contrast, the indirect effect of retributive response via perceived justice on forgiveness was not significant, B = .03, SE = .10 (95% CI = 0.13–0.26). Discussion Replicating Studies 1 and 2, a restorative response (here in the form of an offender apology) led to greater forgiveness, partially mediated by perceptions of justice. Retributive response Third-party apology Offender apology Retributive response Third-party apology Offender apology Justice Retributive 9 Justice Third-party A. 9 Justice Offender A. 9 Justice Justice .58 .76 .51 .11 .18 .54 B .20 .19 .21 .18 .17 .19 – – – – B SE B .19 .26 .16 .04 .07 .19 – – – – 2.90** 3.94*** 2.43* .60 1.05 2.85** .07 .05 .39 .31 N/A .17 .17 .18 .05 .03 .02 .13 .35 – – – b t-value b SE B .41 .31 2.13* 6.39*** – – – t-value .01 .06 .41 .23 .18 .21 .39 N/A B .17 .17 .18 .08 .13 .12 .14 SE B .00 .02 .14 .26 .09 .12 .17 b STEP 3 .03 .33 2.26* 2.96** 1.37 1.70† 2.76** t-value Note. For Justice as dependent variable (D.V.), R2 = .05, F(3, 311) = 5.62; for Forgiveness, in Step 1: R2 = .03, F(3, 311) = 2.91; in Step 2: R2 = .14, F(4, 310) = 12.66; in Step 3: R2 = .18, F(7, 307) = 9.86. † p < .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. Forgiveness Predictor D.V. STEP 2 STEP 1 Table 3. Hierarchical regression results for dependent measures (Study 3) 478 Michael Wenzel and Tyler G. Okimoto Justice and forgiveness Retributive Response 479 –.00(.04) –.02(.07) Third-party apology * Forgiveness ** .14 (.19 ) Offender apology .16* *** .26 ** .19 Control = .26** Retributive response = .06 Third-party apology = .49*** Offender apology = .70*** Feelings of Justice Figure 2. Study 3. Direct and indirect effects of justice response on forgiveness (total effects in parentheses). Third-party apology and retribution – responses that were not inclusive of the offender – did not lead to greater forgiveness even though they both also increased perceptions of justice. Consistent with Study 2, the relationship between justice and forgiveness also depended on the response from which those feelings of justice derived. The relationship was stronger when an apology was the response, irrespective of whether the apology was offered by the offender or a third party. This suggests that social validation of the violated values, which is an element of both offender and third-party apology, is key to a kind of justice experience that is conducive to forgiveness. However, inclusion of the offender in the value consensus, which characterizes an offender apology, seems to be critical for a positive direct effect that adds to the indirect effect via justice, producing a significant total effect of offender apology on forgiveness. In contrast, although not significant, the direct effects tended to be negative (and thus neutralizing any indirect effects) for a thirdparty apology and retributive response, both of which imply an absence of a consensus with the offender and may even imply a distancing from, or social exclusion of, the offender. GENERAL DISCUSSION This research challenges the theoretical views that forgiveness requires victims to sacrifice justice (Aquino et al., 2003; Exline et al., 2000), or that achieving justice promotes forgiveness (Exline et al., 2003; Tripp et al., 2007; Worthington, 2006). In contrast, the current results suggest that both may be true, but that the relationship between justice and forgiveness depends on the way that justice was achieved. Although a restored sense of justice is overall positively related to forgiveness, not all means of justice restoration increased forgiveness. Consistent with the injustice gap and the vigilante model of justice, restorative responses (consensus-seeking or more unilateral offender apologies) increased forgiveness indirectly by restoring justice, as well as directly (in Studies 1 and 3). This direct effect suggests that inclusive and consensus-building restorative responses imply a common identity that facilitates forgiveness (Wenzel et al., 2010; Wohl & Branscombe, 2005). However, we did not measure identity in this research and this therefore remains speculation; this direct effect might merely represent a residual effect due to incomplete mediation caused by methodological limitations and should therefore be interpreted with caution. 480 Michael Wenzel and Tyler G. Okimoto In contrast, inconsistent with the notion of injustice gap and the vigilante model of justice, retributive responses did not lead to greater forgiveness. Although they did help to restore a sense of justice and, thus, apparently indirectly increased forgiveness, this indirect effect seemed to be counteracted by negative direct effects. Although the direct effect of the retributive response was not significant in Study 3, additional processes prevented the indirect effect from translating into a significant total effect. Again, we can only speculate what these processes might be in the absence of evidence showing alternate mediating mechanisms. However, on the basis of justice restoration theory (Okimoto et al., 2008; Wenzel et al., 2008) we would argue that retributive responses imply a competitive relationship, a negative interdependence over status/power restoration, and/or a symbolic distancing of the offender, which undermine feelings of forgiveness. However, a further key to why retributive responses did not seem to promote forgiveness lies in the finding that the relationship between justice and forgiveness was not the same for all means of justice restoration. While we did not find a moderation of the justice-forgiveness link in Study 1, this may be due to the correlational design of the study where the presumed measured moderators – retributive and restorative response – were strongly correlated. In Studies 2 and 3, where the presumed moderators were manipulated and thus independent from another, we found that forgiveness was positively related to justice feelings that derived from a restorative response, but unrelated to justice feelings that derived from retributive responses. These results support the theoretical distinction between retributive and restorative justice (Wenzel et al., 2008), where only the latter, being based on the renewal of consensus about relevant values, is conducive to forgiveness. Once we take into account that the meaning of justice depends on the means of its restoration, the evidence shows that only restorative responses, but not retributive responses, facilitate forgiveness indirectly through feelings of justice. While from our theoretical perspective restorative justice has forgiveness-promoting effects because it implies a value consensus between victim and offender, a shared recommitment to the violated values, there may be alternative theoretical explanations. For example, according to the needs-based model of reconciliation (Shnabel & Nadler, 2008), victims experience an impairment of their sense of power, and restoration of their power would foster their willingness to reconcile. It is conceivable, albeit speculative at this point, that restorative justice affords a greater sense of victim empowerment, whereas retributive justice merely implies offender disempowerment. While both might help to rebalance the scales of power and increase perceptions of justice in victims, it might be that only justice through victim empowerment leads to more forgiveness (Wenzel & Okimoto, 2010). It may be noted that the moderation pattern appeared to differ between Studies 2 and 3, with the retributive response being the significant moderator of the justiceforgiveness relationship in Study 2, but the restorative response being the moderator in Study 3. However, the reason for this difference was actually the control condition, which provided a different baseline in the two studies (see Figures 1 and 2): in Study 2 there was a stronger significant relationship between justice and forgiveness than in Study 3. It is possible that in Study 2 the default relationship was cooperative (the offender was a fellow student), while in Study 3 the default relationship was competitive (co-worker vying for organizational status). In other words, the difference between retributive and restorative was very similar between the studies, but the control condition moved. Justice and forgiveness 481 Study 3 also included a third-party apology as a response, which is a kind of hybrid response as it involves the social validation of values (like an offender apology) but not with, and by implication perhaps against, the offender (like a third-party punishment). Interestingly, the results showed a similar moderation of the justice-forgiveness relationship as for offender apology, but the absence of a total effect on forgiveness as for the retributive response. The latter again might be due to the symbolic exclusion (or non-inclusion) of the offender, which diminishes a shared identity that would facilitate forgiveness. The significant moderation effect suggests that the social validation of values (with or without the offender) is crucial for the justice experience to be conducive for forgiveness. This is consistent with findings that third-party communications that acknowledge the wrong-doing can facilitate forgiveness through providing validation and indicating social consensus (Eaton et al., 2006; Wenzel & Coughlin, 2012). It is possible that victims who see the violated values socially validated feel less need to demonstrate unforgiveness towards the offender, less need to demonstrate indignation as a symbolic reassertion of those values. A limitation of this research is that it did not include an equivalent differentiation between retributive responses inflicted by the victim (i.e., revenge) versus retributive responses inflicted by a third party. The measure in Study 1 included items of both kinds of retributive response, whereas the experimental manipulations in Studies 2 and 3 focused on third-party punishment only. It is possible that victim-inflicted revenge and third-party punishment have quite different implications. For example, a victim might experience an act of revenge as cognitively inconsistent with the idea of a subsequent opposite act of forgiveness. In contrast, when a punishment is imposed by a third party, victims might not see any contradiction in their own behaviour; they might even start to feel sympathy for the suffering offender and therefore feel more forgiveness towards the offender. However, from this perspective Studies 2 and 3, focusing on third-party punishment, offered a conservative test of our predictions; and there was no evidence for a sympathy effect, or any beneficial effect of punishment for that matter, on forgiveness. While the hypothetical nature of Studies 2 and 3 represents a limitation, the recall of real-life events in Study 1 provides complementary evidence. On the other hand, Study 1 is limited by its correlational design, which does not allow causal inferences and, with the presumed moderators being strongly correlated, is sub-optimal for the detection of distinct moderation effects. However, the experimental designs of Studies 2 and 3 make up for these weaknesses. The consistency across different methods, scenarios, measures of forgiveness and restorative versus retributive responses should also add confidence in the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, the complex pattern of results speaks against the possible criticism that the scenario studies constituted a transparent methodology, in which the participants merely responded on the basis of their lay theories. In sum, regarding the relationship between justice and forgiveness, not all forms of justice are made equal. A sense of justice restored through restorative responses promotes forgiveness, but justice restored through retributive responses does not. Acknowledgement This research was supported by a grant from the Australian Research Council, DP0877309. 482 Michael Wenzel and Tyler G. Okimoto References Aquino, K., Grover, S. L., Goldman, B., & Folger, R. (2003). When push doesn’t come to shove: Interpersonal forgiveness in workplace relationships. Journal of Management Inquiry, 12, 209–216. doi:10.1177/1056492603256337 Boon, S. D., & Sulsky, L. M. (1997). Attributions of blame and forgiveness in romantic relationships: A policy-capturing study. Journal of Social Behavior & Personality, 12, 19–44. Darby, B. W., & Schlenker, B. R. (1989). Children’s reactions to transgressions: Effects of the actor’s apology, reputation and remorse. British Journal of Social Psychology, 28, 353–364. doi:10. 1111/j.2044-8309.1989.tb00879.x Eaton, J., Struthers, C., & Santelli, A. G. (2006). The mediating role of perceptual validation in the repentance-forgiveness process. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 1389–1401. doi:10.1177/0146167206291005 Exline, J. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Expressing forgiveness and repentance: Benefits and barriers. In M. E. McCullough, K. I. Pargament, & C. E. Thoresen (Eds.), Forgiveness: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 133–155). New York, UK: Guilford. Exline, J. J., Worthington, E. L., Jr, Hill, P., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Forgiveness and justice: A research agenda for social and personality psychology. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 7, 337–348. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0704_06 Fehr, R., Gelfand, M. J., & Nag, M. (2010). The road to forgiveness: A meta-analytic synthesis of its situational and dispositional correlates. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 894–914. doi:10.1037/ a0019993 Goffman, E. (1967). Interaction ritual: Essays on face-to-face interaction. Oxford, UK: Aldine. Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]. Retrieved from http://www. afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf Hogan, R., & Emler, N. P.. (1981). Retributive justice. In M. J. Lerner & S. C. Lerner (Eds.), The justice motive in social behavior (pp. 125–144). New York, UK: Academic Press. Karremans, J. C., & Van Lange, P. A. (2005). Does activating justice help or hurt in promoting forgiveness? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41, 290–297. doi:10.1016/j.jesp. 2004.06.005 Lazare, A. (2004). On apology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. McClelland, G. H., & Judd, C. M. (1993). Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 376–390. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.114.2.376 McCullough, M. E., Rachal, K. C., Sandage, S. J., Worthington, E. L., Jr, Brown, S. W., & Hight, T. L. (1998). Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships: II. Theoretical elaboration and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1586–1603. doi:10.1037/ 0022-3514/75.6.1586 McCullough, M. E., Root, L. M., & Cohen, A. D. (2006). Writing about the benefits of an interpersonal transgression facilitates forgiveness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 887– 897. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.887 McCullough, M. E., Worthington, E. L., Jr, & Rachal, K. C. (1997). Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 321–336. doi:10.1037/00223514.73.2.321 Okimoto, T. G., & Wenzel, M. (2008). The symbolic meaning of transgressions: Towards a unifying framework of justice restoration. In K. Hegtvedt & J. Clay-Warner (Eds.), Advances in group processes (pp. 291–326). Bingley, UK: Emerald. Okimoto, T. G., & Wenzel, M. (2009). Punishment as restoration of group and offender values following a transgression: Value consensus through symbolic labelling and offender reform. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 346–367. doi:10.1002/ejsp.537 Okimoto, T. G., Wenzel, M., & Feather, N. T. (2012). Retribution and restoration as general orientations toward justice. European Journal of Personality, 26, 255–275. doi:10.1002/per. 831 Justice and forgiveness 483 Okimoto, T. G., Wenzel, M., & Platow, M. J. (2010). Restorative justice: Seeking a shared identity in dynamic intra-group contexts. In E. Mannix, M. Neale, & E. Mullen (Eds.), Research on managing groups and teams: Fairness and groups (Vol. 13, pp. 205–242). Bingley, UK: Emerald. Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879– 891. doi:10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42, 185–227. doi:10. 1080/00273170701341316 Scher, S. J., & Darley, J. M. (1997). How effective are the things people say to apologize? Effects of the realization of the apology speech act Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 26, 127–140. doi:10. 1023/A:1025068306386 Schlenker, B. R., & Darby, B. W. (1981). The use of apologies in social predicaments. Social Psychology Quarterly, 44, 271–278. Shnabel, N., & Nadler, A. (2008). A needs-based model of reconciliation: Satisfying the differential emotional needs of victim and perpetrator as a key to promoting reconciliation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 116–132. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.1.116 Strelan, P., Feather, N., & McKee, I. (2008). Justice and forgiveness: Experimental evidence for compatibility. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 1538–1544. doi:10.1016/j.jesp. 2008.07.014 Strelan, P., Feather, N., & McKee, I. (2011). Retributive and inclusive justice goals and forgiveness: The influence of motivational values. Social Justice Research, 24, 126–142. doi:10.1007/s11211011-0132-9 Tripp, T. M., Bies, R. J., & Aquino, K. (2007). A vigilante model of justice: Revenge, reconciliation, forgiveness, and avoidance. Social Justice Research, 20, 10–34. doi:10.1007/s11211-007-0030-3 Wenzel, M., & Coughlin, A.-M. (2012, April). Third-party communications and forgiveness. Paper presented at the 41st annual conference of the Society of Australasian Social Psychologists (SASP), Adelaide, Australia. Wenzel, M., & Okimoto, T. G. (2010). How acts of forgiveness restore a sense of justice: Addressing status/power and value concerns raised by transgressions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 401–417. doi:10.1002/ejsp.629 Wenzel, M., & Okimoto, T. G. (2012). The varying meaning of forgiveness: Relationship closeness as a moderator of forgiveness effects on feelings of justice. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 420–431. doi:10.1002/ejsp.1850 Wenzel, M., Okimoto, T. G., Feather, N. T., & Platow, M. J. (2008). Retributive and restorative justice. Law and Human Behavior, 32, 375–389. doi:10.1007/s10979-007-9116-6 Wenzel, M., Okimoto, T. G., Feather, N. T., & Platow, M. J. (2010). Justice through consensus: Shared identity and the preference for a restorative notion of justice. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 909–930. doi:10.1002/ejsp.657 Wohl, M. J. A., & Branscombe, N. R. (2005). Forgiveness and collective guilt assignment to historical perpetrator groups depend on level of social category inclusiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 288–303. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.88.2.288 Worthington, E. L. (2006). Forgiveness and reconciliation: Theory and application. New York, UK: Routledge. Received 12 June 2012; revised version received 2 May 2013