Corporate Treasurer Role: Financial Crisis Impact & Emerging Trends

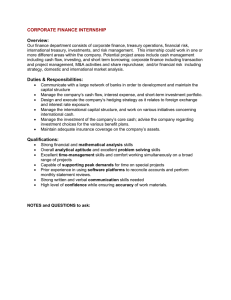

advertisement