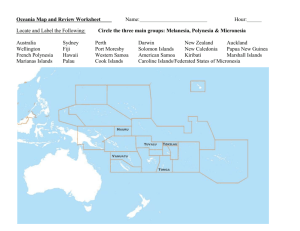

Historical Investigation Project Extended Response: Lachlan Gibson Inquiry Question: Evaluate the influence of geographical factors on Polynesian Expansion. Response: The settlement of Polynesia1, though a lengthy process, did not occur at a steady pace. While the pace of settlement during the Lapita expansion2 was relatively consistent, there is evidence pointing to an almost 2000-year gap before rapid settlement of the eastern islands of Polynesia. This hiatus in Polynesian expansion, now known as the ‘long pause’, was likely affected by several geographical factors. An island void at the edge of the Lapita expanse coupled with unfavourable sailing conditions would have significantly decreased the probability of successful voyages, while a decreasing ability of islands to support sustained human settlement would have left little incentive for further exploration. The ‘long pause’ was likely affected by the geographical isolation of Polynesia. The region of Polynesia is unique, in that it the largest non-continental region settled by humanity. As such, it provided a unique challenge for the peoples living there. Expansion into Polynesia was not as simple as slow land migration, it required boats, and seafaring knowledge. However, the Lapita people from the island of New Guinea had no difficulty traversing the open ocean between islands in the western most part of Polynesia, with dated archaeological evidence suggesting that islands such as Vanuatu, New Caledonia, and Fiji had all been reached by 1500 BCE, and islands as far out as Samoa and Tonga by around 800 BCE.3 But the chain of geographical evidence from west to east goes cold at Samoa for almost 1800 years, with the earliest dated evidence from French Polynesia being from c.1050 CE.4 This bizarre gap is easily explained, however. Samoa and Tonga mark the western edge of an island void in the region between 190 and 200-degrees longitude, where the average distance between islands approaches 270km, which is almost 80% larger than distances further to the west.5 In fact, a predicted peak in sea levels around the end of the Lapita expansion may mean that this distance was even greater.6 As such, it’s likely that the Lapita people lacked the seafaring vessels and knowledge that would allow them to traverse such a large distance, resulting in the ‘long pause’. This is further supported by the archaeological evidence in east Polynesia, which indicates rapid settlement of east Polynesia after arrival from the west.7 While the sheer distance between the islands at the eastern edge of the Lapita expansion and those in east Polynesia likely affected Polynesian expansion, it was not the only factor at play that could have affected the ‘long pause’. The strength and direction of trade winds and oceanic currents in the region also likely played a large part in restricting Polynesian expansion. The Polynesian’s used sailing vessels that were heavily reliant on wind. These vessels functioned well in west Polynesia, where easterly wind spells are the most common in the region. However, in the central region encompassing Tonga, Samoa and the island void directly to the east, easterly spells are extremely uncommon8. As such sailing in that area would have required 1 A region of the Pacific Ocean, generally defined by a triangle between Aotearoa (New Zealand), Rapa Nui (Easter Island), and Hawai’i 2 The term given to the settlement of the islands of Melanesia (Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and New Caledonia) and West Polynesia (Vanuatu and Fiji) from c.3500BCE to c. 1500BCE 3 A. Montenegro, R. Callaghan, and S. Fitzpatrick, ‘From west to east: Environmental influences on the rate and pathways of Polynesian colonization’, The Holocene, 24.2 (2014), p. 242. 4 J. Wilmshurst, T. Hunt, C. Lipo, and A. Anderson, ‘High precision radiocarbon dating shows recent and rapid initial colonization of East Polynesia’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108.5 (2011), p. 1815. 5 A. Montenegro et al, ‘From west to east’, p. 245. 6 H. Moriwaki, M. Chikamori, M. Okuno, and T. Nakamura, ‘Holocene changes in sea level and coastal environments on Rarotonga, Cook Islands, South Pacific Ocean’, The Holocene, 16.6 (2006), p. 847 7 J. Wilmshurst et al, ‘High precision radiocarbon dating’, p. 1819 8 A. Montenegro et al, ‘From west to east’, p. 246 thorough knowledge of tacking. When done properly, tacking allows a masted vessel to sail headfirst into the wind, but can easily result in a vessel capsizing without extensive and thorough knowledge of the technique. This possibility of capsizing is of note when considering that westerly winds in central Polynesia are quite strong. Accompany that with the large sails of the Polynesian vessels, and the margin for error would have been extremely slim. Weak surface currents in the region also flow to the west,9 which add even more resistance to progression eastward. Overall, the likelihood of successfully traversing the island void to the east of Samoa and Tonga seems quite slim, an idea supported by computer simulations. They found that only 10% of all voyages from Samoa would be successful, with only 8% of voyages from Tonga being successful.10 Moreover, most successful voyages were during months of high instability in wind patterns, and under El Niño11 conditions, a weather phenom which the people of Polynesia seem to have been unaware of.12 This would have further decreased the odds of a successful voyage to the eastern islands of Polynesia. As such, it seems likely that weather and wind conditions affected the ‘long pause’. While geographical restrictions would have affected the likelihood of successful voyages into the east of Polynesia, the geographical features of the islands could also have affected the incentives to voyage further. The islands of west Polynesia are larger, experience more favourable weather, and are less topographically challenging than those in the east. Of particular note is the considerable decrease in size between Samoa and Tonga when compared to Fiji. With an area of around 2750 and 750km2 respectively, the islands are more than six times smaller than Fiji, with its area of 18000km2. This means that the islands in the far east of the Lapita expanse offer considerably less space to develop housing and crop plantations, and as such are less favourable to human settlement in general. Also of note is the soil composition of Fiji, Samoa, and Tonga. Almost 80% of the soil in Fiji is either unsuitable for, or poses severe limitations to subsistent agricultural practices,13 an amount similar to that of Samoa, where 70% of soil poses severe limitations to farming.14 Tonga has comparatively much more soil suitable for agriculture, around 85% of all soil on the island.15 However, when taking into consideration the total area available, Fiji offers around 3600km2 of land suitable for agriculture, with Samoa and Tonga offering 800km2 and 600km2 respectively. This means that Fiji, and by extent the western islands of the region, would be able to support a larger population, with islands in the east of the region being able to sustain a much lower population. The inhabitants of those islands may have observed this decrease in agricultural capability, and as such, it is possible that the need to expand further into the region was deemed negligible, considering the perceived reward. At first glance, the 'long pause’ seems bizarre. An 1800-year hiatus in the otherwise steady settlement of Polynesia. But thorough evaluation of the geographical factors at play easily explains it. An island void at the eastern edge of the Lapita expanse, combined with unfavourable sailing conditions in the region surrounding Samoa and Tonga would have considerably decreased the probability of a successful voyage to the islands in eastern Polynesia, while a west to east decrease in the capability of islands to support sustained settlement likely left little incentive for further expansion at the time. C. Cenedese and A.L. Gordon, ‘ocean current’, Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/science/ocean-current (Accessed 8/06/2022) 10 A. Montenegro et al, ‘From west to east’, p. 245 11 A climate pattern that describes the unusual warming of surface waters in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, which influences weather in the region. 12 P. Lefale, ‘Ua ‘afa le Aso Stormy weather today: traditional ecological knowledge of weather and climate. The Samoa experience’, Climatic Change, 100.2 (2009), p. 332 13 ‘Maps – Soils of Fiji’, Pacific Soils Portal, https://fiji-psp.landcareresearch.co.nz/maps/ (accessed 13/06/2022) 14 ‘Maps – Soils of Samoa’, Pacific Soils Portal, https://samoa-psp.landcareresearch.co.nz/maps/ (accessed 13/06/2022) 15 ‘Maps – Soils of Tonga’, Pacific Soils Portal, https://tonga-psp.landcareresearch.co.nz/maps/ (accessed 13/06/2022) 9 Reference List: - - - - - Cenedese, C. and Arnold L. Gordon, ‘ocean current’, Encyclopedia Britannica (2022), [online] Available at <https://www.britannica.com/science/ocean-current> [Accessed 08/06/2022] Lefale, P., ‘Ua ‘afa le Aso Stormy weather today: traditional ecological knowledge of weather and climate. The Samoa experience’, Climatic Change (2009), 100.2, pp.317335. Montenegro, A., Callaghan, R. and Fitzpatrick, S., ‘From west to east: Environmental influences on the rate and pathways of Polynesian colonization’, The Holocene (2014), 24.2, pp.242-256. Moriwaki, H., Chikamori, M., Okuno, M. and Nakamura, T., ‘Holocene changes in sea level and coastal environments on Rarotonga, Cook Islands, South Pacific Ocean’, The Holocene (2006), 16.6, pp.839-848. Pacific Soils Portal, ‘Maps – Soils of Fiji’, Pacific Soils Portal (2022), [online] Available at: <https://fiji-psp.landcareresearch.co.nz/maps/> [Accessed 13/06/2022] Pacific Soils Portal, ‘Maps – Soils of Samoa’, Pacific Soils Portal (2022), [online] Available at: <https://samoa-psp.landcareresearch.co.nz/maps/> [Accessed 13/06/2022] Pacific Soils Portal, ‘Maps – Soils of Tonga’, Pacific Soils Portal (2022), [online] Available at: <https://tonga-psp.landcareresearch.co.nz/maps/> [Accessed 13/06/2022] Wilmshurst, J., Hunt, T., Lipo, C. and Anderson, A., ‘High-precision radiocarbon dating shows recent and rapid initial human colonization of East Polynesia’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2010), 108.5, pp.1815-1820.