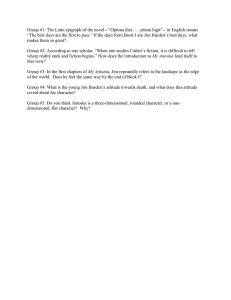

The Journal of Social Studies Research 44 (2020) 35e50 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect The Journal of Social Studies Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jssr Critical historical inquiry: The intersection of ideological clarity and pedagogical content knowledge Brooke Blevins a, *, Kevin Magill a, Cinthia Salinas b a b Baylor University, USA University of Texas at Austin, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Accepted 12 September 2019 Available online 30 September 2019 This paper presents the relationship between pedagogical content knowledge and political/ideological clarity as a framework for understanding the nuanced interpretations and applications of critical social studies pedagogy and practice. Using a qualitative case study research design, this study explores the decision-making process of two novice social studies teachers as they decide if and how to utilize critical historical inquiry within their classrooms. Findings indicate that teachers' use of critical historical inquiry is informed by their subject area consciousness and political and ideological clarity which is cultivated through personal, schooling, and communal experiences. However, we also find that a teacher's pedagogy is significantly strengthened when political and ideological clarity are coupled with pedagogical content knowledge to ensure a more developed enactment of critical historical inquiry is reached within the social studies classroom. © 2019 The International Society for the Social Studies. Published by Elsevier, Inc. Keywords: Critical pedagogy Historical thinking Critical historical inquiry Teacher education Political clarity The official school curriculum, embedded in textbooks, state standards, and pre-packaged resources, plays a significant role in determining what history is recounted, remembered, and understood in social studies classrooms (Levy, 2014; VanSledright, 2008). As Trouillot (1995) suggests, the historical narrative that is transmitted in schools “is a particular bundle of silences” (p. 27) created by “the uneven contribution of competing groups and individuals who have unequal access to the means for such production” (p. xix). Indeed, the official historical narrative told in schools often reflects a singular, uncomplicated, if not erroneous, portrait of America's past (Alridge, 2006; Naseem-Rodriguez, 2015; Santiago, 2017), a historical rendition that marginalizes particular peoples and perspectives (Epstein, 2009; Ortiz, 2014; Rowe & Tuck, 2017; Schmidt, 2010) and is patterned through dominant themes of individualism, progress and victory (Carretero, 2017; Barton & Levstik, 2004). The consequence of official school narratives is that we “cannot and will not help students construct personally empowering civic understandings if they see their purpose as the transmission of a predefined story” (Levinson, 2012, p. 132). In contrast, the civic identity, agency, and membership of communities might be more richly reflected in a historical narrative that is more inclusive (Grever & Stuurman, 2007; Haste & Bermudez, 2017; Kirshner, 2009; Levy, 2014; Salinas, Vickery, & Naseem Rodriguez, 2018; Zembylas, 2017) and viewed in social studies classrooms as “the places where the contending voices in the debate over what history means, or should mean, in a democracy come together” (Stearns, Seixas, & Wineburg, 2000, p. 3). * Corresponding author. E-mail addresses: Brooke_blevins@baylor.edu (B. Blevins), Kevin_magill@baylor.edu (K. Magill), cssalinas@austin.utexas.edu (C. Salinas). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssr.2019.09.003 0885-985X/© 2019 The International Society for the Social Studies. Published by Elsevier, Inc. 36 B. Blevins et al. / The Journal of Social Studies Research 44 (2020) 35e50 Teachers play a pivotal role in bridging and disrupting the divide between the official curriculum and students' own lived experiences and understandings. Teacher decision making and agency is central in understanding how we might co-create social studies classrooms with students that are more transformational, inclusive and reflective of our diverse student population. The complexity of teachers' decisions have been distilled through several frameworks which include notions related to teacher identity (Britzman, 2003; Richardson, 2003), intellectual biography (Shulman, 1986), disciplinary knowledge in their classrooms (Adler, 2008; Grant, 2003; Wineburg & Wilson, 2001), and ideology (Fr anquiz, Salazar, & DeNicolo, 2011; Matias, 2016; del Carmen Salazar, 2013). In social studies classrooms, teachers' historical positionality (VanSledright, 2002) and historical stances (Levstik & Barton, 2001) are also deeply shaped by their familial and informal and formal learning experiences (Adler, 2008; Britzman, 2003; Richardson, 2003). Despite the potential agency in pedagogical decisionmaking, some social studies teachers tend to accept the hegemonic norms associated with the official narrative, which often results in a pedagogy of silence or avoidance related to student positionalities (Epstein, 2009; Gramsci, 1971; Levstik, 2000). For others who endeavor to present or inspire a more complex and empowering narrative, questions of historical stances (Levstik & Barton, 2001), positionality (Maher & Tretault, 2001; VanSledright, 2002), metadiscourse (Wineburg, 2001) and verisimilitude (Lowenthal, 1998) are most salient. The purpose of this study is then to illuminate why and how teachers might introduce alternative and counter narratives in their classrooms and how this approach is related to a teacher's critical ideology and pedagogical content knowledge. Using a qualitative research design including vignettes and subsequent analysis, we explore the decision making process of two novice social studies teachers as they decide if and how to utilize critical historical inquiry within their classrooms. In the next section, we establish a framework for the enactment of critical historical inquiry centered on the notion of political and ideological clarity (Bartolome, 2004) and pedagogical content knowledge (Shulman, 1986). Critical historical inquiry In recent decades, the field of social studies has experienced a flurry of research in the field of historical thinking and vesque & Clark, 2018; Reisman, 2012; Seixas, 1993, 2017; inquiry (Winebug, 2001; Cunningham, 2007; Endacott, 2010; Le Seixas & Peck, 2004; VanSledright, 2002; Wineburg, Martin, & Monte-Sano, 2012). Teachers focused on historical thinking and inquiry encourage their students to seek out and analyze new information relevant to their (or other's) historical questions. When done effectively, historical inquiry offers a way for students to begin to construct their own interpretations and understanding of past events through the reading and interpretation of primary and secondary sources. Relatedly, historical thinking involves cultivating the skills to evaluate, analyze, and corroborate historical evidence. Often teaching historical thinking involves asking questions of a source to reveal critical elements of its essential nature (e.g. Seixas & Peck, 2004). Historical inquiry and thinking are distinct but related and both involve active investigation and analysis rather than passive acceptance of knowledge. In abandoning the traditional banking model of teaching that involves a listing and memorization of factsdnames and dates (Freire, 2007)d historical inquiry provides the opportunity for teachers and students to think like a historian, construct a narrative, and present a story through an evidentiary trail (Blevins & Salinas, 2012; Bain, 2006; Barton & Levstik, 2004; Monte-Sano, 2011a, Reisman, 2012; Sexias, 1993; VanSledright, 2011; Wineburg, 2001). Therefore, historical thinking and inquiry might be understood as agentic and empowering processes. Regardless of the possibility of introducing other perspectives that might otherwise be marginalized by the official school curriculum, there are no guarantees that teachers and students will recognize the problematic function of historical narrative and thus introduce those difficult histories that include racism, classism, sexism and so forth or capture the importance of the civic identities, agency and membership of communities of color, women or the LGBTQ community. As a result, we have called for the use of critical historical inquiry (Blevins & Salinas, 2012; Blevins, Salinas, & Talbert, 2015; Salinas, Blevins, & Sullivan, 2012). A 'critical' conceptualization of historical inquiry includes an explicitly conscious examination of the dominant, yet often erroneous, metanarratives found within the school curriculum as well as an interrogation of the ways in which structures of power continue to reproduce oppressive, nation-building narratives in the school curriculum. Through critical historical inquiry, students begin to understand, disrupt and challenge the official curriculum and explore new and diverse perspectives that recognize and honor the unique experiences of linguistically and culturally diverse communities (Franquiz & Salinas, 2011). Critical historical inquiry, with its roots in critical theory and pedagogy, provides an opportunity to challenge these dominant historical narratives by focusing on critiquing traditional forms of knowledge, creating a dialogue between students and teachers, utilizing student experience, and introducing subjugated narratives into the curriculum. However, the enactment of critical historical inquiry may be enhanced or hindered by multiple influences including the subject area knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge of teachers and the underlying purposes they attach to teaching. Regardless of the potential for critical historical inquiry to create more inclusive and just representations of the past, a teacher's identity, dispositions, historical positionality, and historical stances often inform if and how this pedagogical tool will be used in the classroom (Thornton, 1991). A critical analysis of pedagogy reveals power inherent to a teacher's interpretation and negotiation of their contextual realities, which becomes particularly relevant in teacher-proofed contexts that are heavily reliant on uniform and prescriptive standards and high stakes testing. The negotiation of ideology, schooling and pedagogy also influence a teacher's ability to enact critical historical inquiry within these highly regulated contexts. In previous work, we have highlighted the important role teachers' intellectual biography, historical positionality, and content knowledge play in their enactment of critical historical thinking (Blevins & Salinas, 2012; Blevins, Salinas, & Talbert, B. Blevins et al. / The Journal of Social Studies Research 44 (2020) 35e50 37 2015; Salinas, Blevins, & Sullivan, 2012). In this article, we expand this discussion to include an exploration of teachers’ political and ideological clarity (Bartolome, 1994, 2004) and pedagogical content knowledge (Shulman, 1986). Conceptual structure Throughout our work, we have discovered that a teacher's political and ideological clarity is essential in the enactment of critical pedagogical practices such as critical historical thinking: “Political clarity refers to the ongoing process by which individuals achieve ever-deepening consciousness of the sociopolitical and economic realities that shape their lives and their capacity to transform such material and symbolic conditions” (Bartolome, 2004, p. 98). Ideological clarity is the “process by which individuals struggle to identify and compare their own explanations of the existing socioeconomic and political hierarchy with the dominant society” (Bartolome, 2004, p. 98). In examining themselves and their place within a larger educational context, teachers begin to develop political and ideological clarity around issues of power and relation (Authors). Teachers who embody political and ideological clarity recognize that teaching is not apolitical, but is, instead, both ideologically and politically driven. We do not claim political and ideological clarity is a monolithic concept that can be absolute in its applications related to teaching or society, but rather that teachers demonstrating political and ideological clarity understand teaching as a means of challenging oppressive norms and aspects of the social relations of production. Emerging from Freire's (2007) notion of critical consciousness, a teacher's political and ideological clarity is about naming and analyzing the ways hegemonic ideology privileges certain groups and political approaches, including particular historical narratives. Therefore, we suggest that a social studies teacher who demonstrates political and ideological clarity will likely be more inclined to employ pedagogical practices that expose the political nature of the curriculum and seek to create transformative educational opportunities like critical historical inquiry. Political and ideological clarity are foundational to critical pedagogy; however, they alone do not ensure a critical pedagogy par excellence (Magill & Salinas, 2018). A teacher would also have to possess the requisite pedagogical knowledge for a critical pedagogy to unfold within the social studies disciplines. Consider here the ways a teacher's understanding of a concept like primitive accumulation (Harvey, 2005)- or the history of the ways capital and social hierarchies have come to exist-would inform their teaching. These perspectives might be used to trouble the ways students understand and contend with normed social relations. While this type of political and ideological clarity is essential, we further claim critical social studies teachers must also demonstrate the ability to translate those critical ideologies into classroom practice. These teachers then, possess what Shulman (1986) calls pedagogical content knowledge (PCK). As VanSledright (2002) points out, teachers must have both deep subject matter and pedagogical content knowledge as well as deep procedural knowledge in order to effectively teach historical thinking. Monte-Sano (2011b) argues that teachers must also be able “to comprehend students' disciplinary thinking and to anticipate, recognize, and respond to students' conceptions of the subject” (p. 261). To effectively nuance an oppressive historical narrative requires teachers to know where to obtain materials and resources, understand how to read difficult texts, recognize how to analyze mysterious artifacts and resources, and most importantly, be proficient in their translation of these skills to students. Knowledge of how the historical narrative is deliberate in its design to lift one narrative up and negate another narrative is a prerequisite to political and ideological clarity. Teaching to transgress traditional and oppressive historical narratives not only involves exposing how power has come to marginalize most, but also having the critical knowledge essential in disrupting dominant narratives. Knowing how to and what to insert into the traditional narrative go hand in hand in enacting critical historical inquiry (Blevins & Salinas, 2012; Magill & Salinas, 2018). As Segall (2004) suggests, pedagogical content knowledge also involves “examining the pedagogical layers that are already imbued” in curricular materials and deciding if one wants to work with or against those “pedagogical invitations” (p. 500). For social studies teachers who want to utilize critical historical inquiry, this means performing a critical examination of the official curriculum and maintaining an understanding of how to utilize primary and secondary sources to disrupt these oppressive narratives. Our conceptual structure, then, is two-fold. First, we suggest examination of political and ideological clarity will allow us to explore the ways in which teachers conceptualize analysis and relation in the social studies classroom. Second, we understand pedagogical content knowledge to be vital in the pedagogical enactment of political and ideological clarity. This study examines how two novice teachers’ utilized critical critical historical inquiry within their classrooms and the ways that their political and ideological clarity and pedagogical content knowledge informed these decisions. Method We employed a critical instrumental collective case study design for the purpose of this study (Agostinone-Wilson, 2013; Creswell & Poth, 2018; Kincheloe & McLaren, 2005; Stake, 2005; Yin, 2013) in which we sought answers to the research questions and explored the emic issues that surfaced during interactions with the participants. We approached this study critically to understand the relations between power/ideology, curricular interpretation and pedagogical practice. Therefore, we conducted a critical case study, which demands the researcher consider ways power is inherent to teaching, research, social context, and is subject to a political agenda (Kincheloe & McLaren, 2005). Social studies teachers' decisions about when and how to implement critical pedagogical strategies like critical historical inquiry are rooted in their political and ideological clarity and pedagogical content knowledge. There are a number of other considerations that factor into the decision making process. As such, this study centered around two primary questions: 1) How do novice teachers' political and ideological 38 B. Blevins et al. / The Journal of Social Studies Research 44 (2020) 35e50 clarity and pedagogical content knowledge inform their use of critical pedagogical practices such as critical historical inquiry? 2) What other factors act upon a novice teachers’ enactment of critical pedagogical practices such as critical historical inquiry? As teacher educators who have become increasingly aware of our own privilege and of the ways in which dominant forces silence and oppress alternative voices and perspectives, we are interested in how teachers, many of whom function in the same privileged space as ourselves and others like those in this study who do not, seek to disrupt hegemonic discourses in an attempt to help create emancipatory awareness raising possibilities for their students. Our hope in conducting this type of research is to shed light on how to better prepare teachers who will engage their students in social studies teaching and learning that is more inclusive and just. Participants and context Participants in this study were purposefully chosen because they demonstrated a commitment to critical pedagogy during their preservice teacher education experience and engaged their students in critical pedagogical practices such as critical historical inquiry. As instructors for their two-semester methods course sequence, we emphasized more critical (via race, class, religion and gender) renditions of history using the work/readings of authors such as Seixas (1993), Barton and Levstik (2004); VanSledright (2008), and Wineburg (2001). Additionally, the work of authors such as Salinas, Blevins, & Sullivan (2012); Epstein (2009); and Peck and Seixas (2008) were used to introduce more inclusive ways of viewing historical thinking. In earlier research, we concluded that more raced, classed, and gendered understandings of disciplinary knowledge, ambitious teaching, and ideological stances allowed preservice teachers opportunities to dissect marginalizing historical narratives and introduce more viable renditions of history (Blevins & Salinas, 2012; Blevins, Salinas, & Talbert, 2015; Salinas, Blevins, & Sullivan, 2012; Salinas & Blevins, 2013; Salinas & Sullivan, 2007; Salinas & Castro, 2010). The qualitative multiple case study included a total of six novice teacher participants; however, for the purposes of this paper we only report on two participants. We focus on only two participants for the purpose of this paper for two main reasons. First, both participants taught in the same middle school setting at the time of the study. Second, while Abigail and Antonia had both previously demonstrated emerging political/ideological clarity and a commitment to critical pedagogical practices in their social studies methods coursework, the ways in which they were able to enact their critical dispositions in the classroom differed significantly. As such we explore the two participants’ ability to engage students in critical historical inquiry and enact critical historical thinking. At the time of the study, the two participants, Abigail and Antonia, both taught at the same school, Jackson Middle School. Jackson Middle School has a fairly diverse student population, with 23% African American, 40% Latino/a, 29.7% White, and 6.6% Asian Americans and nearly half (48%) of the students “economically disadvantaged.” Abigail is a biracial (African American and White) female. At the time of the study, Abigail was a second year 8th grade U.S. History teacher. Antonia, a Latina female, was a first year 7th grade Texas History teacher. Abigail and Antonia both demonstrated elements of political and ideological clarity and engaged in critical pedagogical practices in their methods coursework and field experiences. For instance, in their lesson plans and classroom teaching they often introduced subjugated narratives, engaged students in examination of issues of social justice and multiple perspectives, and incorporated student experience and voice (Alfaro, 2008; Apple, 2004). However, their enacted classroom practices were markedly different. This paper; therefore, was our exploration of how and why their enacted curriculum was so different. Data analysis Four types of data (Yin, 2003) were used to investigate the posed research questions: (a) course artifacts/documents, (b) classroom artifacts/documents, (c) observations, and (d) interviews. During the course of the study, we conducted five observations of each participants' classroom instruction. We developed an observation protocol based on our conceptual structure (Creswell, 2018). Observations attended to teachers use of critical pedagogical practices including critical historical thinking and inquiry, including noting if and how teachers challenged traditional forms of knowledge and official historical narratives, engaged students in dialogue, utilized student experience, and introduced subjugated narratives in their teaching. Following each observation, we conducted short interviews to follow up and clarify any questions or concerns we had about the observation. In these interviews, we asked participants to describe their intended purposes for the lesson and decisions regarding the design and implementation of the lessons. Three semi-structured interviews were also scheduled and conducted with each participant. The first interview was conducted prior to the first classroom observation and was intended to ask participants to describe their intellectual and schooling biographies and their purposes for teaching and teaching social studies in particular. The second interview was conducted midway through the semester as a way of gathering information about the participant's current school content, including their interactions with colleagues and administrators. The third interview was conducted after the final classroom observation and sought to explore participants overall thoughts on the year, student outcomes, and their continued development as teachers. In both the second and third interview, we also asked participants to describe their pedagogical practices and rationale behind their practice. These three interviews helped to contextualize observation data, interrogate teachers pedagogical content knowledge, and illuminate teachers political and ideological clarity. After coding the data, we utilized a recursive, constant comparative process of examining the data, noting similarities, differences, categories, concepts, and ideas that were evident. This inductive method ensured that participants’ voices and ideas determined the patterns and themes and, subsequently, the findings (Glaser & Strauss, 1965; Miles, Huberman, & B. Blevins et al. / The Journal of Social Studies Research 44 (2020) 35e50 39 ~ a, 2013). Cross-case analysis was used to improve external and internal validity for this study. Yin (2003) recommends Saldan using cross-case analysis as a powerful tool allowing for analysis of each case as a subunit (within case analysis), between the different subunits (between case analysis), or across all of the subunits (cross-case analysis). The patterns, themes, and comparisons of interviews, observation, and artifact data led to the findings included in this paper. To examine the research question, “How do novice teachers' political and ideological clarity and pedagogical content knowledge inform their use of critical pedagogical practices such as critical historical inquiry?” we provide a detailed analysis of the two participants' experiential knowledge and its influence on their understandings of critical historical thinking. Following this detailed exploration of experiential knowledge, we then present data to attend to the second research question, “What other factors act upon a novice teachers' enactment of critical pedagogical practices such as critical historical inquiry?” by providing vignettes of each participant's classroom practice. We then analyze how and why the participant was or was not able to enact critical historical thinking in her classroom. We note the dialectical negotiations (Agostinone-Wilson, 2013) between critical ideology and consciousness and pedagogical enactment as we analyze the ways participant teachers understood and enacted political and ideological clarity and pedagogical content knowledge in their classrooms. Articulating political and ideological clarity in the social studies Both Abigail's and Antonia's personal, communal, and cultural experiences played a significant role in shaping their political and ideological clarity and desire to teach social studies from a more critical perspective (Magill & Salinas, 2018; , 2008; Queen, 2014, Solorzano & Delgado Bernal, 2001). These perspectives emerged as they endeavored to Bartolome provide content and experiences to nuance students' ability to engage in critical historical thinking and inquiry. Below we describe Abigail and Antonia's experiential knowledge and its impact on their espoused critical consciousness Abigail The daughter of a White father and African American mother, Abigail's educational experiences were deeply shaped by the biracial makeup of her family (Epstein, 2009). Abigail consistently credited her father with encouraging her to have a passion for history and to question the status quo: “I love history and stuff. But, my dad, he made it a purpose, even though he was White, to learn about other narratives, especially African American history. So I learned a lot of African American history growing up.” Abigail's familial background, including the narratives she encountered during this time, shaped the way she encountered her schooling experiences: “So when I went to high school, I found there was something different from what I was being taught at home and what was being taught at school. I began to question, and I would go home and we would talk about these things. Why are these things left out?” Not only had Abigail learned contrasting stories about history, but she also saw how these narratives were often excluded from what was traditionally taught in schools: “So in 11th grade we totally skipped over the chapter on slavery. And I was like how can you do this? ‘Cause I know all this information about it. And that's when I kind of figured they were leaving some stuff out.” In other words, Abigail had a heightened consciousness of how the official social studies curriculum silenced, omitted, and delegitimized certain narratives, particularly African American narratives (Apple, 2004; Brown & Brown, 2010; King, 2017; King & Womac, 2014; Vickery, 2017; Woodson, 2017). It was in college that Abigail's knowledge of alternative historical perspectives and interpretations of the past began to influence her desire to become a social studies educator. Abigail credits several of the history courses she took at university as pivotal in solidifying her desire to “tell the other story.” It was, however, Abigail's social studies methods coursework that she pointed to as having the greatest impact on helping her fuse her critical consciousness and knowledge of other narratives with curricular and pedagogical practices. Describing the impact of these courses, Abigail noted: I knew about all these alternative narratives, but I didn't know what to do with them. I knew lecture and things like that. We would just have students regurgitate. And then in Dr. Gomez's class I learned about things like historical thinking and started to figure out what I could do. Abigail's methods coursework provided an opportunity for her to see how her political and ideological clarity could be infused with particular pedagogical practices, like critical historical inquiry, which highlights the complex and unresolved nature of history. Abigail came to her teacher education program with a critical consciousness, or a specific awareness of problematic social narratives and desire to expose issues of race, class, gender, and sexuality within the classroom context. While this disposition was largely shaped by her familial, community, and personal background as well as by informal and formal schooling experiences, her methods coursework provided the transformative tools Abigail needed to see how her critical consciousness and knowledge might be used in actual classroom practice. As such, Abigail's political and ideological clarity and content knowledge base informed her desire to teach social studies for more critical purposes. Describing her purpose in teaching social studies, Abigail said, “I want my students to critique history, what people did in the past and what they thought, what historians think, and what we are teaching them. I want them to think for themselves and question.” Abigail articulated a deep sense of political and ideological clarity, recognizing the political nature of historical interpretation and the need to question dominant interpretations. Furthermore, she highlighted how her political and ideological clarity would inform her teaching practice and her students' learning. 40 B. Blevins et al. / The Journal of Social Studies Research 44 (2020) 35e50 Antonia One of four children, Antonia described her family as working class and “fairly traditional in the Mexican sense.” Antonia cited her great aunt as influencing her desire to teach, particularly her interest in teaching neglected perspectives. Antonia's great aunt, a former English teacher, was an active member of the Chicano movement, dining with and providing lodging for Caesar Chavez. The experiences of her Tia were somewhat of a legend in her family, providing a context for Antonia and her family to talk about oppositional narratives and experiences. In many ways, Antonia's aunt represented a “transformational role model” in that she was a visible member of Antonia's “own racial/ethnic and/or gender group who actively demonstrate [d] a commitment to social justice” (Solorzano & Delgado Bernal, 2001, p. 322). Additionally, throughout her childhood and adolescence, Antonia regularly traveled to Mexico to visit her mother's family; as such, Antonia became a regular border crosser both physically as well as culturally and linguistically (Anzaldua, 1999). As a result, she developed knowledge of cultural and linguistic contexts other than that of the United States. During high school, Antonia had a particularly profound experience with one of her English teachers which helped her realize “that there are bigoted notions deeply embedded in the school curriculum.” This teacher had Antonia and her peers read Dee Brown's Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee which detailed the horrific treatment Native Americans received at the hand of the United States government for nearly 100 years: “This was one of those projects I will never forget. It stuck with me. I was like wow, I never knew this stuff, why haven't I heard about this before?” This experience which included working with a narrative about a marginalized population added to Antonia's burgeoning political and ideological clarity and her commitment to highlighting underrepresented and neglected perspectives. Like Abigail, it inspired her to ask for other resources as she began to think more critically as a historian and teacher engaged in perpetual inquiry. Antonia took a variety of courses at the university that helped increase her knowledge of subjugated stories, including courses on social movements in the United States, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Mexican Revolution, which helped illuminate narratives to which she had not been previously exposed and added to her desire to teach the underdog's perspective. Describing her desire to become a teacher, Antonia noted: I decided that by teaching history I would make more of a difference probably because I kind of consider myself an underdog, a minority. So I am always rooting for the underdog. In a sense I want to teach the underdog's point of view. Antonia's familial, community, and schooling experiences provided the opportunities to gather knowledge of multiple, often underrepresented, perspectives and propelled her interest in helping her students develop awareness and knowledge of other perspectives. While Antonia took a number of courses in college that furthered her knowledge of content, particularly her knowledge of counter narratives, like Abigail, she pointed to her social studies methods coursework as providing the means by which she was able to begin incorporating some of this content into her classroom: “I really liked the stuff we did on constructivism and historical thinking. I like DBQs. That stuff is really fun and it gets more out of the kids.” While Antonia noted several of the primary theories presented in her methods coursework, her deep knowledge of critical pedagogical practices seemed somewhat limited, noting it was “fun” but failing to acknowledge its transformative and emancipatory purposes. She did demonstrate an understanding of critical historical inquiry when searching new artifacts as a way to nuance and inform her own ideological clarity; however, she remained unsure of how this work might be done with students. Both Abigail and Antonia articulated a clear understanding of the erroneous and oppressive nature of historical narratives and indicated a desire to disrupt these “bundle[s] of silences” in their classrooms (Trouillot, 1995). In Wertsch's (1998) terms, both had mastered the narratives found in the official curriculum, but neither had appropriated these narratives, and both expressed resistance to these accounts based on their knowledge of alternative perspectives gained through both personal, communal, and schooling experiences. Both Abigail and Antonia had formal and informal learning experiences that allowed them to adopt a critical consciousness and historical positionality that was attentive to the ways in which traditional historical narratives are often exclusionary and oppressive. Abigail and Antonia actively sought out multiple perspectives and knowledge that ran counter to official historical narratives (Kincheloe, 2001). Abigail and Antonia seemed to embody political clarity in their everyday living (Bartolome, 1994). As Bartolome (1994) argues, “teachers working toward political clarity understand that they can either maintain the status quo, or they can work to transform the sociocultural reality at the classroom and school level so that the culture at this micro-level does not reflect macro-level inequalities” (p. 178). Both developed a sense of dissonance between the knowledge they gleaned from their personal and communal experiences, the knowledge they encountered in formal and informal learning experiences, and the narratives they were exposed to in their collegiate experience. Consequently, they wanted to lessen this sense of dissonance for their own students. Abigail's desire to “critique the curriculum” and Antonia's commitment to include the “underdog's perspective” demonstrate the centrality of their experiential knowledge (Freire, 2007; Solorzano & Delgado Bernal, 2001). Specifically, Abigail and Antonia's experiential knowledge informed their political clarity and ideological commitments to exploring critical issues within the social studies classroom and created a foundation for social justice, equality, and empowerment (McLaren, 2003). While Abigail and Antonia seemed to have political clarity and to have articulated notions of critical pedagogy in regard to teaching the social studies, their enacted classroom practice was markedly different. Abigail was quite successful at engaging her students in a critical interrogation of the past while Antonia struggled to do so. Thus, while Abigail and Antonia seemed to embody all of the necessary elements to engage in critical pedagogy, including critical historical inquiry, when they entered their own classrooms, their approach to teaching and learning differed. In the next section, we B. Blevins et al. / The Journal of Social Studies Research 44 (2020) 35e50 41 explore the complex and nuanced processes Abigail and Antonia engaged in as they made decisions about what and how to teach in their classrooms. In order to best characterize each participant's decision-making process, we present a vignette of each participant's classroom practice, highlighting their curricular and pedagogical practices and decisionmaking processes. Each vignette is then followed by a description that highlights three themes that emerged through our cross case analysis. The enacted curriculum: a vignette of abigail The bell rang and the halls at Jackson Middle School filled with rambunctious middle schoolers. Abigail, an 8th grade US History teacher, stood outside her door greeting students as they walked in her classroom. While it was school protocol that each teacher at Jackson Middle School shook hands with students as they walked in the door, Abigail made this practice her own, giving students the more popular fist pound, having meaningful dialogue, and building rapport with each student as he or she entered. The bell rang, the door closed, and Abigail was on. “Alright guys, I need you to get out your journals and work on your Sacagawea warm-up.” Abigail traveled around the room giving each student a two-page article detailing Sacagawea's life, including her abduction from her own tribe, her “marriage” and subsequent pregnancy with French trader Toussaint Charbonaeu, and her “indispensable” involvement with the Lewis and Clark expeditions (Knauer, 2005). The nuanced representation of Sacagawea differed from the textbook account which provided only a cursory reference to Sacagawea's role in the expedition and certainly made no mention of Lewis' thoughts on Sacagawea's indispensableness. Though not formal critical historical thinking, providing the additional article helped students to begin to inquire about how new materials can help nuance historical narratives. Abigail endeavored to scaffold historical thinking and inquiry by posing relevant questions of the text. As students sat in groups of four reading this article, Abigail pulled up the overhead screen to reveal several questions related to historical agency and empathy including “What role did Sacagawea play in the Lewis and Clark expedition?” and “Why is she not given the credit she deserves?” (Reisman & Wineburg, 2012; Seixas & Peck, 2004). Students took several moments to respond to these questions in their journals. The students excitedly turned to their neighbor as they shared their answers with one another. Comments like “She was the guide,” “she's the only reason they survived,” and “I didn't realize she had a baby” resonated from the groups as new historical understandings added to what they had originally understood from the textbook. The discussion among groups continued as Abigail walked around the classroom. The following conversation then ensued: Abigail: Why might Sacagawea not be given the credit she deserves, remember she was a pregnant teenager, who gave birth to a baby on the expedition, she was a Native American. Why might she not have been given the credit she deserves? Student A: Because she was an Indian. Abigail: Because she was a Native American. Student B: Because she was a woman. Abigail: And why might that have caused her not to earn the credit she deserves? Student B: Because the men wanted to take all the glory. Abigail: Perhaps. Even Lewis says in his journal that she is so important, but she is still not given the credit she deserves. Why don't we hear more about Sacagawea? Why is she not talked about much in traditional textbook story we read? Student C: Because she isn't a guy. She's young and pregnant and that's not the story we want to tell people. Abigail: Interesting point….it's not the story we want to hear. So let's continue to consider this question as we work through our next activity. The lesson continued as students progressed through a series of seven stations that contained primary and secondary source material related to the Lewis and Clark expedition. Each station included questions designed to promote historical thinking and inquiry. One of the stations asked students to imagine they are a member of one of the Native American tribes the Lewis and Clark Expedition came into contact with and then write a letter to a neighboring tribe retelling their experience with and impression of Lewis and Clark and their companions (judgment and empathy). At another station, students were asked to use the knowledge they acquired about the Lewis and Clark expedition from primary and secondary sources and explain if they thought the Lewis and Clark expedition would have succeeded without the help of Sacagawea (evidence and agency). At the conclusion of the lesson, Abigail gathered her students back together to reexamine the questions posed at the beginning of class. Students then modified their initial responses based on their examination of additional historical evidence. Detailing the purpose of this lesson, particularly her extensive focus on Sacagawea, Abigail said: I tried to get the students to understand that, yes, the Lewis and Clark Expeditions were a great thing. I mean 1803 Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the U.S., but We also wanted them [students] to think about who was impacted. I wanted them to think about how Native Americans were negatively impacted in a variety of ways. Also, I wanted them to see how crucial Sacagawea was to the expedition and why we never hear much about her. One of my goals is to introduce more women into the curriculum, especially Native Americans. The curriculum is all about White people, so I try to introduce more perspectives. 42 B. Blevins et al. / The Journal of Social Studies Research 44 (2020) 35e50 Abigail's experiential knowledge informed her political clarity including her resistance to the official narrative, understanding of historical positionality, attention to multiple perspectives, and desire to disrupt oppressive historical narratives. Therefore, part of Abigail's approach to a lesson is about revealing the normalization of oppressive historical narratives. However, Abigail's political clarity was also coupled with pedagogical content knowledge that allowed her to engage in the praxis of critical historical inquiry within her classroom. Her comfort facilitating critical pedagogical practices such as critical historical inquiry and dialogue allowed her political and ideological clarity to emerge as a part of her pedagogy. Pedagogical practices Commenting in an interview about her pedagogical decision-making and highlighting the political nature of curricular inclusion, Abigail remarked: One of my main goals this year was to include more minorities into the curriculum. To talk about the other perspectives. To answer the questions, why aren't these people given the credit they deserve? Why don't we study this person more? Why do we choose some people over others? I want them to critique the social studies curriculum. Abigail regularly used historical inquiry as a pedagogical tool to allow students to explore, analyze, and synthesize evidence from multiple perspectives and sources to develop their own perspective and understanding of the past. She encouraged her students to consider the nature of historical narrative and how one's positionality as well as larger ideological influences inform the retelling of the past (VanSledright, 2002). Abigail's success with critical historical inquiry was shaped by several critical pedagogical practices, including her use of big ideas and critical essential questions, her ability to provide ample space, time, and scaffolding for students to wrestle with difficult ideas, and her purposeful practice of creating humanizing spaces for her students. Big ideas The lesson described above highlights the way Abigail framed her lessons around big ideas and essential questions. “A big idea is a question or generalization that is intellectually honest and is cast in a manner that should appeal to students” (Grant & Gradwell, 2010, p. vii). More importantly, Abigail maintained her critical pedagogical focus in addressing big ideas that attended to notions of power, in particular the way that the official social studies curriculum privileged certain perspectives over others. Abigail clearly articulated the purpose of this lesson through the core question (Reisman & Wineburg, 2012) she posed at the beginning of class, “Was Sacagawea given the credit she deserved and why?” As students examined both primary and secondary source documents, they were guided by well scaffolded questions that pointed back toward the core question. By framing her lesson around a big idea and a core question that focused on notions of power, students were encouraged to think about the nature of historical interpretation, positionality, and the official narrative as they examined evidence needed to respond to this question. Space and time Secondly, Abigail provided ample space and time for her students to wrestle with evidence and develop their own interpretations. In both this lesson and others we observed, Abigail was purposeful in scaffolding students' historical thinking and inquiry skills. Over the course of the year, she provided her students with multiple opportunities to interrogate primary sources. Throughout this process, Abigail modeled critical historical inquiry for and with her students through whole-class discussions, small group work, and one-on-one interactions with students. Because of Abigail's methods, her students were able to see how she interrogated historical texts and developed evidenced based interpretations. Repeated throughout her lessons was the question “How did you figure that out?” More importantly, Abigail established a classroom environment in which process was more important than the product. She did not emphasize the “right answer; ” instead she focused on helping students develop the skills and habits of mind necessary to develop reasoned historical interpretations (Nokes, 2013). Abigail valued student voice and provided space and time for her students to wrestle with dissonance as she introduced them to sources that called to question the official historical narrative. Humanizing pedagogy Finally, Abigail engaged in a humanizing pedagogy in which student experience and knowledge were highly valued and where dialogic conversation and learning were encouraged (Bartolome, 1994; Freire, 2007). The cultural and ethnic demographics and interpretive frameworks of Abigail's students compelled her to use critical historical inquiry to help students understand how their own cultural and ethnic experiences fit into a larger historical narrative (Epstein, 2009). Not only was Abigail interested in providing her students with information that challenged the traditional portrayal of Lewis and Clark, but she was also deliberate in highlighting the overarching need to investigate multiple perspectives in order to gain greater understanding of the way power and ideology color the retelling of history. This approach exposed how particular positionalities are reflected in the social studies curriculum and others are not. Abigail's choice to center her lesson around critical core questions, provide space and time for students to engage evidence and develop their own interpretations, and her engagement in a humanizing pedagogy demonstrate her political and ideological clarity in praxis. B. Blevins et al. / The Journal of Social Studies Research 44 (2020) 35e50 43 The enacted curriculum: a vignette of antonia It was a typical Monday morning. The bell rang, and Antonia took her place outside the door of her 7th grade Texas History Classroom. As students approached Antonia's classroom, she greeted each student with a handshake and personally acknowledged each by his or her name. The bell rang again. Antonia greeted the last student, shut the door and walked to the front of the room. Standing behind her desk, she greeted her students who sat in rows facing the front of the classroom. To begin the lesson, Antonia showed a PowerPoint presentation highlighting images from the Galveston Hurricane. As students watched the PowerPoint of photos, Antonia pointed out the widespread damage in the photos. Finishing the slideshow, Antonia flipped on the lights and said, “Galveston was going to be like the next New York City, but in 1900 they had a hurricane and that vastly changed things. Let's talk about why.” Antonia then put up several questions on the overhead screen and asked students to respond to them in their notebooks, including: 1) Why do people continue to resettle and rebuild Galveston Island even though hurricanes continue to ravage this area?; and 2) Though technology has changed and more than 100 years have passed, what has not changed about the effect of natural disasters and hurricanes? Her historical inquiry questions were primarily related to the nature of progress and decline and historical significance in a familiar community. However, students randomly called out answers as the volume in the classroom rose to a level that made it difficult to understand what students were saying and for Antonia to appropriately recognize or help interpret and contextualize student inquiry into this topic. Antonia tried to manage the conversation, but she quickly moved on, encouraging her students to record their answers in their notebooks. Then she said, “Did you know that Cuba had warned the United States about these hurricanes, but we didn't listen? Why don't you think we listened to Cuba?” Without waiting for students to respond, she added, “Maybe the United States just dismissed Cuba thinking that they were too rudimentary to know what they were talking about. How do you think the U.S. felt when Galveston was destroyed by a hurricane they had been warned about?” A frenzy of student responses ensued including a comment from the back of the classroom, “That was just racist that we didn't listen to them.” Antonia quieted the class, said “Good answers,” and then moved on to the next question without any more discussion about Cuba's hurricane prediction. Describing the purpose of this lesson, Antonia said: Today was really simple. We wanted them to compare something from the past to something recent. The Galveston hurricane and other natural disasters and their impact on Texas are part of the curriculum bundles, but we wanted to show that we make mistakes. That it isn't just about nature, but human error is at fault too. We wanted to connect it with bigotry. Why we listen to certain people and not others, like Cuba. Why we care about certain people and not others, in the case of New Orleans. While Antonia recognized the Galveston hurricane was a part of the state mandated or official curriculum, she was also cognizant that the portrayal of this event in the official curriculum provided for a limited and apolitical understanding of this event. Thus, she wanted to help her students move beyond a simplistic understanding of how natural disasters impacted Texas to a more nuanced understanding that tied natural disasters to human action across time (continuity and change), specifically the ways in which cultural politics and discrimination underlie the ways natural disasters are handled. Although Antonia had thoughtfully conceptualized this issue, including the persistent nature of racial and ethnic discrimination in natural disasters, in a fleeting moment everything she had conceptualized and designed dissolved as Antonia pushed through the lesson, failing to recognize and extend her student's comment on racism. In doing so, Antonia's attempts to facilitate critical pedagogy and critical historical inquiry suffered, as students were not able to ask for or share new information. As such, her initial hopes to help her students connect the 1900 Galveston Hurricane to bigotry and inspire further research, vanished. Pedagogical practice While Antonia's experiential knowledge provided the basis for her political and ideological clarity and enhanced her desire to teach social studies in more critical ways, elements of her pedagogical practice hindered the effective introduction of these ideas into her classroom. Unlike Abigail who had great success implementing critical historical inquiry as pedagogical tool, Antonia had more difficulty doing so. Antonia's difficulty was shaped by several pedagogical and curricular practices, including her failure to utilize critical essential questions, her struggle to provide students with the time and scaffolding to wrestle with difficult ideas, and her overwhelming need for control. Lesson framing In the lesson above there was great possibility for Antonia to help introduce a point of view traditionally omitted from the official curriculum, examining the ways in which cultural and economic discrimination influence the impact of natural disasters. Unlike Abigail, who structured her lesson around a critically oriented essential question and a big idea to which she consistently referred, Antonia was more haphazard in her approach to introduce critical perspectives into the lesson. While Antonia indicated she wanted to highlight notions of bigotry and persistent issues of racism, her lesson was not framed around critical questions or a big idea that would allow this issue to be addressed in a coherent fashion. Instead, 44 B. Blevins et al. / The Journal of Social Studies Research 44 (2020) 35e50 she briefly introduced this notion at the end of the class period through a brief and passing question. This lack of focused framing in her lesson made it difficult for students to interrogate the past in ways that promoted critical historical inquiry and interpretation. Space and time Antonia also struggled to provide her students with the space and time they needed to wrestle with difficult and complex ideas. While Antonia seemed to embody political and ideological clarity and expressed a desire to help students explore multiple perspectives and neglected histories, she often rushed through lessons when she was pedagogically uncomfortable, interjected her own opinion when students were slow to respond, and stifled students' opportunity to discuss and develop their own conclusions about the past. In many instances, Antonia became the sage on the stage and engaged in a banking concept of education by telling her students what to think, inhibiting students from fully engaging in their own historical inquiry and interpretations (Freire, 2007). While there were several moments in this lesson where Antonia was able to introduce subjugated narratives (i.e. Cuba's warning and the racial undertones of Hurricane Katrina), she struggled to scaffold learning in a way that allowed her students to make sense of these new perspectives and develop their own understandings of this event and issue. Antonia often engaged in fairly didactic pedagogy relying heavily on the textbook, guided readings, and worksheets as regular pedagogical practice in her classroom because they made it easier for her to compensate for her developing pedagogy. Classroom management Much of Antonia's difficulty engaging students in lessons that promoted critical awareness stemmed from her overwhelming concern with classroom management and control issues. Grossman (1992) has asserted, “For better or worse, classroom management and instruction are eternally married. How teachers manage classrooms enables or constrains the possibilities of teaching, classroom discourse, and student learning” (p. 174). When asked about why she was unable to implement the kinds of lessons she had hoped to, Antonia said, “More than anything it is dealing with the management issues.” Antonia frequently referenced classroom management issues as hindering her teaching practice. To combat her management issues, Antonia planned lessons that she felt would limit the amount of disruption and interaction that would occur in her classroom, lessons that involved little discussion, cooperative learning, or critical thinking. As demonstrated in the opening vignette, Antonia departed from her espoused critical pedagogical approach and adopted a more banking approach to education in which she had more classroom control. Antonia was unable to negate many of the dialectics of practice within curriculum because of her limited PCK (including development of classroom community). Because of her approach, she had great difficulty implementing a broader range of critically pedagogical practices that might have pushed students' understandings of the past beyond the simplistic and narrow pictures painted in the official curriculum. Contextual realities While Abigail and Antonia both had a number of personal and individualized experiences that propelled their use of critical pedagogy and critical historical inquiry, their decision-making was also situated within the larger national, state, and local schooling context. As van Hover (2006) points out, “beginning teachers…are developing their teaching craft within a high-stakes environment: they know and have known no other context” (p. 196). In an era when state and local agencies worked to socialize teachers into the world of standardized testing (McNeil, 2000) and in which “teacher proofed” curriculum was seen as the answer to low test scores, Abigail found a way to “teach in spite of the test, rather than because of it” (Gradwell, 2006, p. 158). On the other hand, Antonia found herself struggling to push against the grain in her teaching (Cochran-Smith, 2001). Abigail taught with a team of three other 8th grade US History teachers. At the beginning of Abigail's tenure at Jackson Middle School, her team met weekly to plan units and daily lessons together. Describing her team, Abigail commented in an interview, “they like to do the same thing every year. It's all about efficiency. Just getting through it, so they have time to review for the state test.” Abigail, on the other hand, suggested she preferred to use cooperative learning, engage her students in historical inquiry, introduce primary sources, and help her students think critically about history. She did not feel the approach the other teachers employed allowed for these kinds of curricular choices and pedagogical practices. As a result, Abigail often did her “own thing” instead of following the plans outlined in the team planning sessions. This meant she was often not in line with the curriculum bundles provided by the district. This fact upset several of her colleagues, but Abigail did not acquiesce. She noted that “my kids are learning, so we don't care.” Abigail did not feel hamstrung by the standards, and she actively encouraged her students to develop a deeper, richer knowledge of the past. When asked about how the state level standardized test impacted her practice, Abigail said, “We feel like if you are a good teacher and you are covering the material well and students are engaging in it well, then they will be fine for the test. It doesn't drive how I teach.” While the state standards did play a role in what content Abigail covered (van Hover, 2006), she consistently pushed beyond the standards to introduce her students to marginalized perspectives and narratives. Antonia also taught with a team of three other Texas History teachers who met several times a week to plan together. Describing her team, Antonia said, “We meet and plan together and most of the time it is just our department chair saying we did this last year, what do you think about this? And most of the time we just do that again.” She reported that most of the lessons suggested by her team involved a heavy reliance on the textbook, guided readings, fill-in-the-blank worksheets, and B. Blevins et al. / The Journal of Social Studies Research 44 (2020) 35e50 45 other lower level activities, a reality with which Antonia was not pleased but to which she often acquiesced. “One of the teachers on my team told me ‘We like what you do, but it is work. You have to dig through stuff, you have to find different books. And the other teachers don't want to do that.’ So it's hard to constantly stand against that.” Throughout our interviews, Antonia described what Apple (2000) calls “intensification.” As control of the content, pedagogy, and assessment shifts outside the classroom, instruction is often intensified on only those things that are easily measured on a standardized test. This often leads teachers to rely on “experts” to tell them what to do instead of trusting their own expertise (Apple, 2000). While Antonia suggested that she pushed against the demands of her “expert” and more seasoned colleagues, she grew weary of fighting her team and ended up acquiescing to many of their curricular and pedagogical choices. This decision often left Antonia with a heavy sense of guilt; as she noted, “In the beginning of the year I was pushing more, I would say ‘I have this idea, let's do stations or historical thinking’. But now I am running out of steam, and they will say ‘here it is’, and I will just say ‘okay’.” Faced with similar organizational and contextual factors as Abigail, Antonia found it difficult to push against the practices of her colleagues and insert her own knowledge of students, content, and pedagogy on a consistent basis. Antonia felt tremendous constraints from the schooling context in which she worked. This reality coupled with Antonia's lack of pedagogical content knowledge often caused her to abandon her political and ideological clarity in her enacted classroom practice. On the other hand, Abigail's political and ideological clarity, knowledge of her students, and genuine concern for their learning propelled her to resist conforming to the practices of her team members. As Cochran-Smith (2001) aptly noted “more than ever we need teachers able and willing to teach against the (new) grain of standardized practices that treat teacher as interchangeable parts anddworsedreinscribe social inequities” (p. 4). Despite the pressures of working within a team of colleagues and the ensuing push to follow the standardized practices required by local, state, and national education entities, Abigail found a way to teach against the grain, to fight against practices that reified social inequities, and to help her students develop emancipatory knowledge. Discussion As teacher educators, we believed that Abigail and Antonia left their social studies teacher education program with political and ideological clarity and the critical pedagogical skills needed to enact critical historical inquiry in their classroom. In conceptualizing their social studies classrooms, these two teachers seemed remarkably similar. However, as classroom observations and interviews revealed, the way their political and ideological clarity played out in their classroom practices was quite different. While both participants articulated an ideological commitment to exploring critical issues, including Abigail's desire to “critique the curriculum” and Antonia's commitment to include the “underdog's perspective,” the application of these ideas were not always realized in their classroom practice. Both were “becoming” (Freire, 2007) as they worked to refine their ideological clarity and PCK, particularly as they related to critical historical inquiry. The findings from this study reveal several important points for discussion. First, political and ideological clarity lies at the heart of a teacher's ability to engage in critical historical inquiry within their classroom. Within the field of social studies education, political and ideological clarity involves an awareness of and resistance to master narratives and attention to multiple perspectives that run counter to official historical narratives. While teachers may have a broader sense of political and ideological clarity, teachers must also understand how this manifests in specific contextsdlike the social studies classroom and how ideology translates into practice. Second, a teacher's pedagogical content knowledge is vital to the unfolding of one's political and ideological clarity and successful use of critical historical inquiry. It follows that a teacher must foster a supportive community of learners to effectively facilitate ideological clarity, subject area consciousness, and pedagogical content knowledge. By subject area consciousness, we are referring to a teacher's knowledge and ability to see and counter oppression represented in the cannon of a particular disciplinary approach or narrative. As noted the relationship between a subject area consciousness and ideological clarity informs the ways teachers will facilitate historical inquiry and if these will simply be disciplinary tools or €nig and Kramer's (2015) suggestion that classroom management is an aspect transformational ones. Findings also support Ko of pedagogical content knowledge. We therefore suggest that a teacher's cultivation of the classroom environment be included as an aspect of PCK for the purpose of this research. In Antonia's case, a well-developed political/ideological clarity and subject area consciousness was stifled because of poor PCK. Therefore, she was unable to fully engage her students critical historical inquiry and instead began to assert classroom control through traditional pedagogy. Abigail's practice represents a well-developed political/ideological clarity, subject area consciousness, and PCK. Fig. 1 provides a visual depiction of the intersection of both political and ideological clarity and pedagogical content knowledge. We argue that political and ideological clarity must be coupled with pedagogical content knowledge in order for teachers to engage in critical historical inquiry and critical praxis at large (Magill & Rodriguez, 2015; Freire, 2007; Gadotti, 1996; Hooks, 2014, McLaren, 2003). Based on this figure, we can imagine a continuum of possibilities related to teachers’ abilities to enact critical historical inquiry in their classrooms. For instance, teachers who have poorly developed political and ideological clarity and weak pedagogical content knowledge may continue to teach in more traditional, didactic ways that reify official historical narratives. On the other hand, teachers who have poorly developed political and ideological clarity but strong pedagogical content knowledge may fall prey to what Bartolome (1994) calls the methods fetish where they may employ a variety of “proven” pedagogical strategies with little regard to the underlying rationale for employing such practices. 46 B. Blevins et al. / The Journal of Social Studies Research 44 (2020) 35e50 For instance, teachers may utilize primary sources in their classrooms, but they may do so in a way that fails to address multiple perspectives, historical positionality, or critical issues. Teachers like Antonia who have well developed political and ideological clarity but weak pedagogical content knowledge may be well intentioned and well informed about the oppressive nature of the official curriculum and aware of subjugated narratives, but not have the pedagogical skills to translate this into practice. These teachers may understand social inequity in curriculum, but fail to consider the ways classroom relation and pedagogy inform historical and contemporary interpretations. Their attempts at critical historical inquiry as a form of praxis may be stifled because of their inability to employ critical pedagogical practices that allow them to translate their critical commitments into learning experiences. While Antonia's classroom practice revealed moments of resistance and elements of historical inquiry, her lack of pedagogical content knowledge and inability to enact critical pedagogical practices that aligned with her political and ideological clarity became evident. Consider her discussions with faculty members in the department meetings. These teachers discouraged Antonia from including other narratives, such as developing lesson centered on historical thinking and inquiry because they believed it was too difficult. The result, she utilized a prepackaged curriculum rather than the approach that aligned with her political/ideological clarity and critical historical thinking. Subsequently, she struggled to resist certain oppressive and dehumanizing pedagogies. As Antonia's lessons failed in these ways, she grew weary of fighting her students and ended up acquiescing to the demands of her team members. Her daily struggle caused her to transmit or bank knowledge thereby limiting her students' ability to meaningfully interpret problematic narratives (Stanley, 2015; Freire, 2007). Like Antonia, many teachers acquiesce to hegemonic power in curriculum and pedagogy when they feel they have little control. In contrast, teachers like Abigail, who have well developed and contextualized political and ideological clarity as well as strong pedagogical content knowledge, are better able to enact critical historical inquiry and critical praxis within their classrooms. They employ critical pedagogical practices that are clearly informed by their political and ideological clarity such as framing lessons around critical essential questions, introducing multiple and competing perspectives, and creating humanizing educational opportunities where students themselves engage in critical reflection and critique. Consequently, when strong pedagogical content knowledge and well-developed political and ideological clarity are coupled, a teacher's ability to resist oppressive and dehumanizing curriculum and pedagogy is also reinforced and nurtured. Abigail's pedagogical content knowledge allowed her to examine the oppressive nature of the curriculum and to contextualize historical thinking, thereby allowing the unfolding of her political/ideological clarity. Further, well-developed PCK allowed the illumination of a humanizing pedagogy (Bartolome, 1994; del Carmen Salazar, 2013; Blevins & Talbert, 2015). Abigail was able to attend to oppressive aspects of educational relations and norms often implicit to classroom pedagogy, curriculum, and authority. Overcoming these often alienating frameworks began as Abigail encouraged a particular type of agentic act unique to the social studies classroom by highlighting ways the transformation of limited narratives frames historical analysis. The experience helped students mutually humanize those often considered the “other” as they came to understanding how and why history can be a tool of oppression or liberation. While Fig. 1 depicts the need for both political and ideological clarity and pedagogical content knowledge, this figure is limited in that it represents only two dimensions involved in engaging in critical historical inquiry in the social studies classroom. Other factors that cannot always be effectively characterized in a two-dimensional figure, such as a schooling Political and Ideological Clarity Well Developed Weak Strong Pedagogical Content Knowledge Not Developed Fig. 1. Essential elements for enactment of critical historical inquiry. B. Blevins et al. / The Journal of Social Studies Research 44 (2020) 35e50 47 context, classroom management, and a teacher's sense of efficacy, also influence teacher decision-making. Despite this limitation, it is important to recognize the powerful coupling of pedagogical content knowledge and political and ideological clarity. As Freire (2007) suggests, we are all constantly becoming. As such, this analysis is not to diminish Antonia's classroom practice, but to highlight the importance of developing pedagogical content knowledge and the skills of critical historical thinking and inquiry that may allow the translation of political and ideological clarity into classroom practice. In her becoming, Antonia must concern herself with negotiating the power inherent to classrooms and schools, examine how to structure her classroom environment in a more humanizing fashion, and pedagogically facilitate transformational disciplinary knowledge or critical historical inquiry before she can begin to support more complex social inquiry and interpretation. In her becoming, Abigail will need to continue to develop her critical praxis by examining those aspects of pedagogy that continue to assert power over students and perhaps unearth new marginalizing historical interpretations, while continuing to refine the ways she teaches historical inquiry and thinking. In the future, Abigail may explore how critical historical inquiry can be utilized to actually transform society, given that her students have discussed the dialectical tension of hetero-masculinity in certain narratives (Magill, 2018). Finally, teachers' contextual realities do indeed influence the way they are able to enact more critical renditions of the past. However, it is not the context in and of itself that matters, but rather the way teachers make sense of these realities. Abigail and Antonia managed the contextual milieu of their schooling context, including working with the curriculum standards, a team of colleagues, and managing a classroom in differing ways. While both participants taught in the same state, a state that produces fairly prescriptive social studies standards for each grade, Abigail was able to push beyond the standards and incorporate critical issues that she believed were vital for her student's learning while Antonia attempted to push against external factors, but for a number of reasons ended up relying heavily on the state curriculum and district curricular bundles to guide her teaching. In addition, Abigail and Antonia negotiated the realities of working with a team, particularly a team who lacked a focus on critical issues and practices, in divergent ways. The findings from this research indicate that without well-developed political and ideological clarity, strong pedagogical content knowledge, and the agency and ability to navigate difficult contextual realities, teachers often find critical historical inquiry difficult and cumbersome and may resort back to more traditional ways of teaching. Implications & Conclusions In the social studies classroom, what content and narratives to address, in what way, and with what pedagogical tools involves a complicated and complex decision-making process. The tales of both Abigail and Antonia illustrate that both political and ideological clarity as well as pedagogical content knowledge inform a teacher's ability to enact critical pedagogical practices such as critical historical inquiry within the classroom. Without the coupling of these elements, the use of critical historical inquiry as a tool to disrupt oppressive historical narratives and content becomes difficult. Teachers demonstrating political and ideological clarity and pedagogical content knowledge have understood their practice through a framework with which they are able to escape some of the trappings of hegemonic schooling. As such, it is important that social studies teacher education programs provide space for preservice teachers to reflect upon the complexity of political and ideological clarity and its implication for classroom practice. Offering explicit opportunities to trouble master narratives and examine subjugated knowledge within a teacher education program is incredibly valuable; however, this alone is not enough. Teacher educators can also provide opportunities for emerging teachers to see models of how political and ideological clarity might actually be enacted through the use of critical pedagogical practices and to debrief how they might do the same in their own classrooms. Explicit modeling of critical historical inquiry by teacher educators and the ensuing debriefing opportunities, is pivotal in helping preservice teachers employ these pedagogical practices within their own classrooms. Modeling not only provides visualization of how this concept works for preservice teachers, but it also demonstrates support for this type of pedagogical content knowledge in the university setting. Many preservice teachers do not have the opportunity to work in classrooms where students are engaged in inquiry based, critically focused, historical inquiry activities (Crocco & Livingston, 2017; Monte-Sano, 2011b). This potential limitation in their field observations may be attributed to the political importance of the standardized curriculum and exams which tend to center the classroom on the teacher and the curriculum itself (McNeil, 2000), but also to the reality that some veteran teachers in the field may lack either the disposition or knowledge to push against heritage narratives. Thus, it becomes important that preservice teacher education models the types of pedagogical practices we want our teachers to employ in their own classrooms. Finally, teacher education programs must also attend to the contextual realities of today's schools and the pressures teachers face in their classrooms. Helping pre-service teachers develop self efficacy within these school contexts should also be central to teacher education programs (Bandura, 1997; Fives, Hamman, & Olivarez, 2007; Poulou, 2007; Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001). While teacher educators cannot instill efficacy within their students, we may be able to assist in strengthening preservice teachers' personal perceptions of efficacy by providing them with opportunities to engage in critical pedagogical practices in settings where they will be supported and encouraged. Thus, in both methods coursework and field experiences, preservice teachers need opportunities to take risks and try new things in a way that is well structured and supervised. If teachers feel more self-efficacy in their ideological and political clarity as well as their pedagogical content knowledge and general abilities as a teacher, they are more likely to take the risk to teach oppositional narratives and introduce more critical 48 B. Blevins et al. / The Journal of Social Studies Research 44 (2020) 35e50 perspectives into the curriculum. This means having explicit conversations with teachers about managing the pressures they will face as critical educators in their classrooms. As Kugelmass (2000) writes: Preparing teachers to work in equitable ways within inequitable educational systems requires developing new teachers' belief in their own power to effect change. This requires more than the development of pedagogical knowledge and skills, social-political expertise and a commitment to educational equity. An internalized sense of agency is also needed to resist dominant ideologies while conforming to institutional demands and, simultaneously, providing effective instruction for children. (p. 179). As teacher educators, if we fail to help teachers develop a sense of efficacy and agency about their teaching practice, they may falter as they negotiate the complexities of decision making in the classroom. As the findings from this study indicate, preparing teachers to teach for critical historical inquiry is not a simple or linear process and may not always ensure classroom enactment. It is essential that we also help new social studies teachers negotiate the ideals of critical praxis, including critical pedagogical practices and the contextual realities of the classrooms they will encounter. Ultimately, political and ideological clarity serve as a precursor to teaching more inclusive versions of history; however, how well equipped teachers are with the pedagogical content knowledge and tools necessary to negotiate the constraints of the teaching context will determine the extent to which teachers will be able to practice their craft in a manner consistent with their views. References Adler, S. (2008). The education of social studies teachers. In L. Levstik, & C. A. Tyson (Eds.), Handbook of research in social studies education (pp. 329e351). New York, NY: Routledge. Agostinone-Wilson, F. (2013). Dialectical research methods in the classical marxist tradition. New York: N: Peter Lang. Alridge, D. P. (2006). The limits of master narratives in history textbooks: An analysis of the representations of Martin Luther King Jr. Teachers College Record, 108, 662e686. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00664.x. Anzaldua, G. (1999). Borderlands la frontera: The new mestiza. San Francisco, CA: Aunt Lute Books. Apple, M. (2000). Official Knowledge: Democratic education in a conservative age. New York, NY: Routledge. Apple, M. (2004). Ideology and curriculum. New York, NY: Routledge. Bain, R. B. (2006). Rounding up unusual suspects: Facing the authority hidden in the history classroom. Teachers College Record, 108, 2080e2114. Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Worth Publishers. Bartolome, L. I. (1994). Beyond the methods fetish: Toward a humanizing pedagogy. Harvard Educational Review, 64, 173e194. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer. 64.2.58q5m5744t325730. Bartolome, L. I. (2004). Critical pedagogy and teacher education: Radicalizing prospective teachers. Teacher Education Quarterly, 31, 97e122. , L. I. (2008). Ideologies in education: Unmasking the trap of teacher neutrality. New York, NY: Peter Lang. Bartolome Barton, K., & Levstik, L. (2004). Teaching history for the common good. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Blevins, B., & Salinas, C. (2012). Critical notions of historical inquiry: An examination of teacher enactment in history classrooms. The Social Educator, 30(2), 13e22. Blevins, B., & Talbert, T. (2015). Challenging the neo-liberal social studies perspective. In A. Crowe, & A. Cuenca (Eds.), Rethinking social studies education for the 21st century (pp. 23e39). New York, NY: Springer Publishing. Blevins, B., Salinas, C., & Talbert, T. (2015). Critical historical thinking: Enacting the voice of the other in the social studies curriculum and classroom. In C. White (Ed.), Critical qualitative research in social education (pp. 71e90). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing. Britzman, D. (2003). Practice makes practice. New York, NY: State University of New York Press. Brown, K. D., & Brown, A. L. (2010). Silenced memories: An examination of the sociocultural knowledge on race and racial violence in official school curriculum. Equity & Excellence in Education, 43, 139e154. del Carmen Salazar, M. (2013). A humanizing pedagogy: Reinventing the principles and practice of education as a journey toward liberation. Review of Research in Education, 37, 121e148. Carretero, M. (2017). Teaching history master narratives: Fostering imagi-nations. In M. Carretero, S. Berger, & M. Grever (Eds.), Palgrave handbook of research in historical culture and education (pp. 511e528). London, England: Palgrave Macmillan UK. Cochran-Smith, M. (2001). Learning to teach against the (new) grain. Journal of Teacher Education, 52(1), 3e4. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0022487101052001001. Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. L. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among 5 approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication. Crocco, M. S., & Livingston, E. (2017). Becoming an “expert” social studies teacher: What we know about teacher education and professional development. In M. M. Manfra, & C. M. Bolick (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of social studies research (pp. 360e384). Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Cunningham, D. L. (2007). Understanding pedagogical reasoning in history teaching through the case of cultivating historical empathy. Theory & Research in Social Education, 35, 592e630. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2007.10473352. Endacott, J. L. (2010). Reconsidering affective engagement in historical empathy. Theory & Research in Social Education, 38, 6e47. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 00933104.2010.10473415. Epstein, T. (2009). Interpreting national history: Race, identity, and pedagogy in classrooms and communities. New York, NY: Routledge. nquiz, M., & Salinas, C. (2011). Newcomers to the US: Developing historical thinking among Latino immigrant students in a Central Texas high school. Fra Bilingual Research Journal, 34, 58e75. Fives, H., Hamman, D., & Olivarez, A. (2007). Does burnout begin with student-teaching? Analyzing efficacy, burnout, and support during the studentteaching semester. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23, 916e934. nquiz, M., Salazar, M., & DeNicolo, C. (2011). Challenging majoritarian tales: Portraits of bilingual teachers deconstructing deficit views of bilingual Fra learners. Bilingual Research Journal, 34, 379-300. Freire, P. (2007). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum. Gadotti, M. (1996). Pedagogy of praxis: A dialectical philosophy of education. Albany: SUNY Press. Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems, 12, 436e445. Gradwell, J. M. (2006). Teaching in spite of, rather than because of, the test. In S. G. Grant (Ed.), Measuring history: Cases of state-level testing across the United States. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing. Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the prison notebooks of antonio Gramsci. In Q. Hoare, & G. N. Smith (Eds.), Trans. New York, NY: International Publishers. Grant, S. G. (2003). History lessons. Mahwah, CT: Lawrence Erlbaum. Grant, S. G., & Gradwell, J. M. (2010). Teaching with big ideas: Cases of ambitious teaching. New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield Education. Grever, M., & Stuurman, S. (2007). Beyond the canon: History for the twenty-first century. Basingstoke, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. B. Blevins et al. / The Journal of Social Studies Research 44 (2020) 35e50 49 Grossman, P. (1992). Why models matter: An alternate view on professional growth in teaching. Review of Educational Research, 62, 171e179. https://doi.org/ 10.3102/00346543062002171. Harvey, D. (2005). The new imperialism. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. Haste, H., & Bermudez, A. (2017). The power of story: Historical narratives and the construction of civic identity. In M. Carretero, S. Berger, & M. Grever (Eds. ), Palgrave handbook of research in historical culture and education (pp. 427e447). London, England: Palgrave Macmillan UK. Hooks, B. (2014). Teaching to transgress. New York, NY: Routledge. van Hover, S. D. (2006). Teaching history in old dominion. In S. G. Grant (Ed.), Measuring history: Cases of state-level testing across the United States. Greenwich, CT: Information Age. Kincheloe, J. L. (2001). Getting beyond the facts: Teaching social studies/social sciences in the twenty-first century. New York, NY: Peter Lang. Kincheloe, J. L., & McLaren, P. (2005). Rethinking critical theory and qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 163e177). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. King, L. J. (2017). The status of black history in US schools and society. Social Education, 81(1), 14e18. King, L. J., & Womac, P. (2014). A bundle of silences: Examining the racial representation of black founding fathers of the United States through Glenn Beck's founders' Fridays. Theory & Research in Social Education, 42, 35e64. Kirshner, B. (2009). “Power in numbers”: Youth organizing as a context for exploring civic identity. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 19, 414e440. Knauer, K. (Ed.). (2005). The making of America: Life, liberty and pursuit of a nation. New York, NY: Time Books. € nig, J., & Kramer, C. (2015). Teacher professional knowledge and classroom management: On the relation of general pedagogical knowledge (GPK) and Ko classroom management expertise (CME). ZDM: The International Journal on Mathematics Education, 48(1e2), 139e151. Kugelmass, J. W. (2000). Subjective experience and the preparation of activist teachers: Confronting the mean old snapping turtle and the great big bear. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16, 179e194. vesque, S., & Clark, P. (2018). Historical thinking: Definitions and educational applications. In S. Metzger, & L. Harris (Eds.), The Wiley International Le handbook of history teaching and learning (pp. 119e148). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell. Levinson, M. (2012). No citizen left behind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Levstik, L. (2000). Articulating the silences: Teachers' and adolescents' conceptions of historical significance. In P. Stearns, P. Seixas, & S. Wineburg (Eds.), Knowing, teaching and learning history: National and international perspectives (pp. 284e305). New York, NY: New York University Press. Levstik, L., & Barton, K. (2001). Committing acts of history: Mediated action, humanistic education, and participatory democracy. In B. Stanley (Ed.), Social studies research for the 21st century (pp. 119e148). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing. Levy, S. A. (2014). Heritage, history, and identity. Teachers College Record, 116(6), 1e34. Lowenthal, D. (1998). The heritage crusade and the spoils of history. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Magill, K. R. (2018). Critically civic teacher perception, posture, and pedagogy: Negating civic archetypes. The Journal of Social Studies Research. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jssr.2018.09.005. Magill, K. R., & Salinas, C. (2018). The primacy of relation: Social studies teachers and the Praxis of critical pedagogy. Theory & Research in Social Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2018.1519476. Magill, K. R., & Rodriguez, A. (2015). A critical humanist curriculum. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies, 12(3), 205e227. Maher, F. A., & Tetreault, M. K. T. (2001). The feminist classroom: Dynamics of gender, race, and privilege. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Matias, C. E. (2016). White skin, black friend: A fanonian application to theorize racial fetish in teacher education. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 48, 221e236. McLaren, P. (2003). Life in schools: An introduction to critical pedagogy in the foundations of education (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon. McNeil, L. (2000). Contradictions of school reform: Educational costs of standardized Testing. New York, NY: Routledge. ~ a, J. (2013). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldan Monte-Sano, C. (2011a). Beyond reading comprehension and summary: Learning to read and write in history by focusing on evidence, perspective, and interpretation. Curriculum Inquiry, 41, 212e249. Monte-Sano, C. (2011b). Learning to open up history for students: Preservice teachers' emerging pedagogical content knowledge. Journal of Teacher Education, 62, 260e272. Naseem- Rodríguez, N. (2015). Teaching about angel Island through historical empathy and poetry. Social Studies and the Young Learner, 27(3), 22e25. Nokes, J. D. (2013). Building students' historical literacies: Learning to read and reason with historical texts and evidence. New York, NY: Routledge. Ortiz, R. (2014). An indigenous peoples' history of the United States. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. Peck, C., & Seixas, P. (2008). Benchmarks of historical thinking: First steps. Canadian Journal of Education, 31, 1015e1038. Poulou, M. (2007). Personal teaching efficacy and its sources: Student teachers' perceptions. Educational Psychology, 27, 191e218. Queen, G. (2014). Class struggle in the classroom. In E. W. Ross (Ed.), The social studies curriculum: Purposes, problems, and possibilities (4th ed., pp. 313e334). Albany, NY: SUNY Press. Reisman, A. (2012). Reading like a historian: A document-based history curriculum intervention in urban high schools. Cognition and Instruction, 30(1), 86e112. Reisman, A., & Wineburg, S. (2012). Text complexity in the history classroom: Teaching to and beyond the common core. Social Studies Review, 51, 24e29. Richardson, V. (2003). Preservice teacher beliefs. In J. Raths, & A. C. McAninch (Eds.), Teacher beliefs and classroom performance (pp. 1e22). Greenwich, CT: Information Age. Rowe, A. C., & Tuck, E. (2017). Settler colonialism and cultural studies: Ongoing settlement, cultural production, and resistance. Cultural Studies e Critical Methodologies, 17(1), 3e13. Salinas, C., & Blevins, B. (2013). Examining the intellectual biographies of pre-service teachers: Elements of "Critical" Teacher knowledge. Teacher Education Quarterly, 40(1), 7e24. Salinas, C., & Castro, A. J. (2010). Disrupting the official curriculum: Cultural biography and the decision making of Latino preservice teachers. Theory and Research in Social Education, 38, 428e463. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2010.10473433. Salinas, C., & Sullivan, C. (2007). Latina/o teachers and historical positionality: Challenging the construction of the official school knowledge. Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy, 4, 178e199. Salinas, C., Blevins, B., & Sullivan, C. (2012). Critical notions of historical thinking: When official narratives collide with other narratives. Multicultural Perspectives., 14(10), 18e27. Salinas, C., Vickery, A., & Naseem Rodriguez, N. (2018). The GI Forum, Felix Longoria and El movimiento: Understanding the Latina/o civil rights movement through critical historical inquiry. In W. Blankenship (Ed.), Teaching the struggle for civil rights, 1948-1976 (pp. 145e156). New York: Peter Lang Publishing Group. Santiago, M. (2017). Erasing differences for the sake of inclusion: How Mexican/Mexican American students construct historical narratives. Theory & Research in Social Education, 45, 43e74. Schmidt, S. J. (2010). Queering social studies: The role of social studies in normalizing citizens and sexuality in the common good. Theory & Research in Social Education, 38, 314e335. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2010.10473429. Segall, A. (2004). Revisiting pedagogical content knowledge: The pedagogy of content/the content of pedagogy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20, 489e504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2004.04.006. Seixas, P. (1993). Historical understanding among adolescents in a multicultural setting. Curriculum Inquiry, 23(3), 301e327. Retrieved from http://www. jstor.org/stable/1179994. Seixas, P. (2017). A model of historical thinking. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 49, 593e605. 50 B. Blevins et al. / The Journal of Social Studies Research 44 (2020) 35e50 Seixas, P., & Peck, C. (2004). Teaching historical thinking. In A. Sears, & I. Wright (Eds.), Challenges and prospects for Canadian social studies (pp. 109e117). Vancouver, Canada: Pacific Educational. Shulman, L. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15, 4e14. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X015002004. Solorzano, D., & Delgado Bernal, D. (2001). Examining transformational resistance through a critical race and LatCrit theory and framework: Chicana and Chicano students in an urban context. Urban Education, 36, 308e342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085901363002. Stake, R. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 443e466). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Stanley, W. B. (2015). Social studies and the social order: Transmission or transformation? In W. C. Parker (Ed.), Social studies today: Research and practice (pp. 27e34). New York, NY: Routledge. Stearns, P. N., Seixas, P., & Wineburg, S. (Eds.). (2000). Knowing, teaching, and learning history: National and international perspectives. New York, NY: New York University. Thornton, S. J. (1991). Teachers as curricular-instructional gatekeepers in social studies. In J. Shaver (Ed.), Handbook of research on teacher and learning in social studies (pp. 237e284). New York, NY: Macmillian. Trouillot, M. (1995). Silencing the past. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17, 783e805. VanSledright, B. A. (2002). Search of America's past. New York, NY: Teachers College Press. VanSledright, B. (2008). Narratives of nation-state, historical knowledge, and school history education. Review of Research in Education, 32, 109e146. VanSledright, B. A. (2011). The challenge of rethinking history education: On practices, theories, and policy. New York, NY: Routledge. Vickery, A. E. (2017). “You excluded us for so long and now you want us to be patriotic?”: African American women teachers navigating the quandary of citizenship. Theory & Research in Social Education, 45, 318e348. Wertsch, J. V. (1998). Mind as action. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Wineburg, S. (2001). Historical thinking and other unnatural acts. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. Wineburg, S. S., Martin, D., & Monte-Sano, C. (2012). Reading like a historian: Teaching literacy in middle and high school history classrooms. New York, NY: Teachers College Press. Wineburg, S., & Wilson, S. M. (2001). Peering at history through different lenses: The role of disciplinary perspectives in teaching history. In S. Wineburg (Ed.), Historical thinking and other unnatural acts: Charting the future of teaching the past. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. Woodson, A. N. (2017). “There ain't no white people here!”: Master narratives of the civil rights movement in the stories of urban youth. Urban Education, 52(3), 316e342. Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed. Vol. 5). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Yin, R. K. (2013). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). Sage Publications, Inc. Zembylas, M. (2017). Teacher resistance to engage with ‘alternative’ perspectives of difficult histories: The limits and prospects of affective disruption. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 38(5), 659e675.