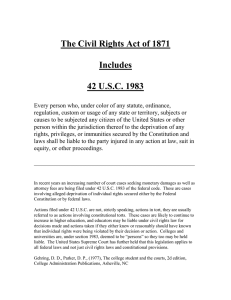

CIVIL RIGHTS – FALL 2014 – COACH K Introduction to § 1983 and Bivens Actions Introduction Course Overview It’s about constitutional tort litigation and constitutional remedies It deals with the question of what remedies are available to someone who suffers a violation of their constitutional rights in regular tort litigation, it’s damages There are barriers to suing a cop in tort @ state law state court not a good place to be The answer rests with § 1983, providing a remedy against someone who violates constitutional rights while acting under color of state law; individuals may sue state actors who violate their constitutional or federal statutory rights in FEDERAL COURT History of § 1983 Came onto the books in 1871 as a means by which Congress enforced the 14th Amendment; Congress used its power under § 5 to pass legislation that was appropriate to affect the guarantees of DUE PROCESS and EQUAL PROTECTION 2 waves of legislation: (1) post-Civil War (13th & 14th Amendments); (2) post-1960s, prohibiting racial discrimination in places of public accommodation, federally-assisted programs, employment discrimination, all derived from the commerce clause 13th Am: no state action component; congressional legislation to enforce had to be just rationally related 14th Am: not related to race; there is a state action requirement (which leads into “under color of state law”) BUT, § 1983 didn’t mean anything until after Monroe, which sparked litigation at a high rate We have a vast body of law that pretty much developed over night (~ 30 years); the courts haven’t had time to sit back and reflect on it; it’s an immediate response to specific problems It’s also a very politicized area of law; the entire basis of the claim raises a federalism concern with using the federal courts to crack down on state actors (the individual is bypassing the state system) THUS, as a different majority of the Court takes over, it switches directions; it doesn’t overrule its prior decisions SO the result is things not being linear or consistent; considerations policy involved and workload of the court (a sense that the Court has burst its bounds) 1983 also deals w/ things that we don’t think of as civil rights claims, ex. takings claims; it reaches into all sorts of areas (zoning, environmental, & education), thus is raises the issue of being an overly broad statute § 1983: Every person who under color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or usage . . . subjects or causes to be subjected any citizen of the U.S. . . . to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution and its laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an action at law § 1983 Monroe v. Pape (U.S. 1961): facts—officers broke into home, ransacked it, and detained the people and brought them to the station; they didn’t file charges in violation of the 4th Amendment; the individuals brought suit for damages under 1983, alleging that the officers had no arrest warrant or search warrant & acted under color of the statutes of IL & Chicago; Monroe wanted damages for the violation of his 4th Am rights (this was novel at this point) the district court dismissed, appellate court affirmed, & the Supreme Court reversed as to the OFFICERS ONLY; RULES Why this case was unique Seeking DAMAGES for a constitutional violation; usually the constitutional violation is invoked as a defense in criminal proceedings (here, motion to suppress the evidence obtained as a result of the violation) Historically, the Constitution was a defense/shield; here, he was using it as a sword; to get damages can the Constitution function as a sword? Must assert deprivation under color of statute of right guaranteed here against unreasonable searches in violation of the 4th Amendment Congress intended to give a remedy to those who were victim of a violation of § 1983 The federal remedy is supplemental to the state remedy; the state remedy need NOT be first sought & refused here before the federal remedy is invoked (thus, the fact that IL outlaws unreasonable searches and seizures is no barrier to this suit in federal court) Purposes of § 1983 1 To override certain kinds of state laws: this would apply to explicitly unconstitutional state laws; by 1871, there weren’t a lot of facially unconstitutional state laws To provide a remedy where state law is inadequate: example of African-Americans in Kentucky not being able to testify To provide a federal remedy where the state remedy, though adequate in theory, is not available in practice because the state is unwilling to enforce the law (“it was their lack of enforcement that was the nub of the difficulty”): this is merely lack of enforcement HERE, the cops argue that they weren’t acting under color of state law because they were in violation of the state law; the Court did not agree the Court didn’t limit “color of law” to what the state allows them to do; they DID act under color because they used their authority as cops to do what they did Color of law means authority of law and they were exercising power that they RECEIVED FROM THE STATE (color of law = color of state authority) ANALYSIS of the Court First: what power does the Constitution give Congress? The power to legislate against individuals who are abusing their state power? 14th Am is against the state & § 5 gives Congress the power to enforce it against the state; the Court held that abuse of state power is state action b/c we’ve recognized state action when the action is in exercise of state power in violation of state law, thus Congress has the power to regulate action that is using state authority but in violation of state law Second: did Congress intend to reach this conduct? What did Congress mean when it used the term “under color”? Did it intend to get after persons who violated state law? The Court looks @ 1983’s 3 main aims & used the lack of enforcement purpose for this case the thrust of the statute is to get at the lack of enforcement by allowing a claim against the police ***KKK: the state’s weren’t enforcing laws against them! Congress was responding to a state of lawlessness in the South & the Klan was responsible for the state not doing anything about it; there were remedies on the books that individuals couldn’t actually invoke (ex. was lynching) Problem: Congress couldn’t reach the private party, KKK, b/c § 5 of the 14th Am only reaches to state action (today, we’d think commerce clause); so they provided a remedy against those enforcing the law but actually not enforcing it and abusing their power Issue of stare decisis as to what “under color” means Term from criminal civil rights legislation from § 242; Screws: criminal civil rights statute would allow prosecution of a person who used state authority but violated state law; the Court adopts this definition for purposes of § 1983; it really uses Classic’s definition “misuse of power” Is there a mens rea requirement? The criminal statute requires that the violation be willful, so does § 1983? NO § 1983 doesn’t have the word in it like § 242; criminal statutes have to be read to not be vague; and the nature of the claim is different, § 1983 should be read against the background of tort law Municipal corporations WERE NOT within the ambit of § 1983; this has changed to where now they are (Monell v. Dep’t of Social Servs.); also, states are not “persons” that can be sued under § 1983 (Will v. Mich. Dep’t of State Police) TODAY, the city would be held liable, too DISSENT Congress intended to cover only instances of injury for which redress was barred in the state courts because some statute, ordinance, etc., sanctioned the grievance complained of (here, the state didn’t sanction the officers’ actions, so they shouldn’t be liable) The Court used the reasoning of United States v. Classic misuse of power, possessed by virtue of state law and made possible only b/c the wrongdoer is clothed with the authority of state law, is action taken “under the color of state law” Screws v. US: under color of state law does not only include action taken by officials pursuant to state law The Court determined this is a federal right in federal court Going to state court wouldn’t really solve the problem here; you have politically elected state officials as the litigators and judges they want to get reelected Federal jurisdiction is important for independence and broader venue The federal remedy is supplementary to the state law remedy BUT it allows a bypassing of the state system—“it is no answer that the state has a law which enforced would give relief” [DISSENT: thinks 2 federal courts should only step in if the state is unwilling or unable to enforce the law; otherwise, you deprive the state of their ability to fix its own problems first; judicial restraint argument] Notes on Monroe What effect did it have: expanded the use of § 1983; gave a broad reading to “under color”; did away w/ the notion that Congress could only reach misconduct that the state authorized or tolerated so that it amounted to government “custom or usage” and thus Congress couldn’t reach actions of state officials who violated state law b/c it wasn’t state action; Monroe—they were USING state power as an instrument for abuse It allowed the Constitution to act like a sword; used offensively to sue someone who violates constitutional rights; it’s a federal right in federal court (jurisdiction is not conferred by § 1983) Side notes Federal forum: federal question (§ 1331) and civil rights claims (§ 1343(a)); § 1331 NOW doesn’t have an AIC requirement, so parties just use this now to invoke federal jurisdiction; § 1343(3) specifically gives federal jurisdiction over claims that someone acting under color of state law deprived them of constitutional rights AND this stems from the same piece of legislation that created § 1983 (see Thiboutot); common practice, invoke both § 1343(3) and § 1331 Benefits of federal forum: § 1983 gives you attorney’s fees (§ 1988); There’s no ceiling on § 1983 damages like states have on tort claims (no notice of claim, for example) Less procedural hurdles than brining a tort action Federal law still applies in state court but federal courts may be more willing to enforce the law on the state officials Federal courts are better run (some belief) Different jury (if you’re in the Western District, you’re drawing from the smaller counties, less minority representation; less likely to have people that have been in jail/dealt w/ law enforcement) Attorney’s fees are available to prevailing parties Jury trial—tort liability and “actions at law” are covered by the 7th Amendment’s jury trial guarantee Suits Against Federal Officials Overview What would’ve happened if the cops who broke into Monroe’s apartment in violation of the 4th Amendment were federal agents and not Chicago police? Monroe couldn’t have sued under § 1983; the federal officials are not acting under state law; they’re acting under federal law There is no statute that functions as a federal analogue to § 1983, providing a damages remedy against federal officials who violate constitutional rights Bivens addresses the question of whether there’s a remedy available for someone who suffers a constitutional violation at the hands of a federal agent or someone who’s acting under the color of federal law the case is virtually the same as Monroe Bivens (U.S. 1971) [claims against FEDERAL officials who violate the Constitution; federal analogue to § 1983] Facts: 4th Amendment case w/ similar violations to Monroe; plaintiff was DAMAGES; using the Constitution as a sword; but can’t bring a § 1983 suit and there’s not another statute The Court held that he could sue for damages because the FBI violated his 4th Am rights; it didn’t matter that there wasn’t a statute on point Reasoning different than a tort b/w 2 private individuals b/c “an agent acting—albeit unconstitutionally— in the name of the US possesses a far greater capacity for harm than an individual trespasser exercising no authority other than his own” Rules The 4th Amendment is a limitation on the exercise of federal power regardless of whether the state in whose jurisdiction that power is exercised would prohibit or penalize the identical act if engaged by a private citizen A person whose 4th Amendment rights are violated by a federal agent acting under color of federal law may recover damages If the petitioner could demonstrate an injury consequent upon the violation by federal agents of his Fourth Amendment rights, is entitled to redress his injury through a particular remedial mechanism normally available in federal courts Defendants argue this should be brought in state court in tort the 4th Amendment is relevant as preventing the agent from asserting the proper exercise under federal authority; the Court doesn’t agree: 3 We’re dealing with a unique federal right with contours that are different from and independent from the contours of state law: Nature of the 4th Amendment claim: it’s not just a defense at state law; it has an independent role; state law and 4th Amendment protect different interests; it’s not like trespass where you can just call the cops—the plaintiffs here felt like they HAD to abide by the FBI States can’t seek to limit the scope of the federal interest So then we have an independent right; something that’s sufficient to be a legally protected interest—that also provides the basis for a claim The remedy can be compensatory damages: The Court can imply a direct remedy under the Constitution; they do so with equitable relief The Court cites to Marbury v. Madison if there’s a right there’s a remedy What the case is not: Federal fiscal policy and congressional employee not acting in violation of the Constitution but in excess of the authority delegated to him by Congress this is a special factor counseling hesitation in the absence of congressional action (it’s a substantive area that’s so sensitive that the court shouldn’t go there without congressional direction BUT this is NOT one of those areas here) No explicit declaration that persons injured by federal officers in violation of the 4 th Amendment may recover money damages no congressional declaration of availability of an alternative remedy (here, Congress was silent) Concurrence (Harlan): Congress does not have to explicitly grant the federal courts power to give damages for violations of constitutional rights by federal agents; if they can grant equitable relief, they should be able to grant damages; courts have the power to ensure those rights are protected & damages does that; just b/c the conduct won’t be deterred shouldn’t prevent him from getting damages Whether authorizing a damages remedy is something that is uniquely in Congress’ hands or something that the court has the power to do when Congress has granted a right via a statute, the Court can give a remedy for violation of that statute; it should be NO DIFFERENT from rights guaranteed by the Constitution Furthermore, the Court already grants equitable relief for constitutional violations so they’ve implied a remedy for constitutional law before (ex. school desegregation case in D.C.; equitable relief for EP violation) DIFFERENCES: = source of the right & the type of implied remedy these weren’t keeping the Court from distinguishing the two HERE, the claim is like a tort claim that is normally compensable (trespass, invasion of privacy, etc.); whether damages are appropriate or “necessary” (§ 5) it is necessary here b/c damages are the only thing that’s going to do any good here (“For people in Bivens’ shoes, it is damages or nothing”) Historical examples: Title 9 of the Civil Rights Act which prohibits gender discrimination in education; it guarantees the right to equal treatment but it doesn’t specify a remedy it’s a controversial idea & has roots in Marbury v. Madison Dissents (Burger): federalism concerns (re: separation of powers); this is judicial legislating—the Court is exercising a power that it doesn’t have; Congress should decide legislatively if there should be some sort of remedy; Congress did that with § 1983 but has not enacted the federal analogue (merely take out the “state” limitation) The Court lacked power to do this Concern that if the Court had the power, it shouldn’t: Congress is better suited to determine the appropriate scope of any remedy & Congress is better suited to determine if that’s where courts should spend their time (the majority doesn’t ignore this) (Black): this is judicial legislating; Congress never created a CAX for violations of federal officials (only for state officials); concern w/ burden on federal courts IMPLICATONS How far does this extend? Struggle in terms of (1) the constitutional claim being asserted & (2) how much we should be deferential to congressional action The Court expanded Bivens in the early days but has more recently refused to extend it anymore & has cut back on the interpretation Expansion: Passman and Carlson Davis v. Passman (U.S. 1979) [NO ALTERNATE REMEDY AND NO SPECIAL FACTOR] 4 Facts: Congressman filed female administrative assistant based on gender discrimination; the Congressman had no been reelected; she sued claiming her 5th Am EP rights were violated (D.C. = federal law; reading EP as an aspect of DP); Supreme Court held she had a cause of action and the federal court had jurisdiction and that damages was appropriate relief Those who have no effective means other than the judiciary to enforce her rights must be able to invoke the jurisdiction of the court for the protection of their justiciable constitutional rights = no alternative remedy (dude couldn’t rehire her b/c he didn’t have the job anymore) No special factors counseling hesitation (perhaps with the Speech/Debate clause but it doesn’t have anything to do with personnel decisions) Carlson problem [NO ALTERNATE REMEDY] Facts: wrongful death case for son killed by prison guards based on racial prejudice by refusing to give him necessary medical treatment; should they be able to sue in federal court? This is an 8th Amendment claim—a right to be free from deliberate indifference to serious medical needs (it states a substantive claim) Whether a Bivens action is appropriate: Analysis Is there a right independent of state law that there’s a federal interest in? Contours of the 8 th Amendment, looking to see whether it’s an independent right; the Court says YES Is there an independent interest? If so, the court will imply a remedy Whether one of the factors in Bivens goes against implying a remedy? Counseling hesitation: prisons have special concerns that require close discipline and security measures not used in a free society; determining how a prison is run is a sensitive decision that the courts aren’t fit to tackle BUT here this is a tangential question as to whether everyone deserves medical care, so no special factor counseling hesitation Alternate remedy: FTCA—there is a possibility of one; suing the government in tort (for medical malpractice); BUT the FTCA isn’t as good; it doesn’t have to be a perfectly equal alternative remedy, though Court Uses the specific language from Bivens, congressional declaration that there’s an alternative remedy (nothing the FTCA says it’s an alternative); if Congress hasn’t declared it as an alternative, we shouldn’t assume that Congress intended for it to function as an alternate remedy also argue that it’s not an adequate remedy b/c there’s a prohibition against punitive damages when suing an individual officer & no right to a jury trial (it all depends upon whether the state allows the claim); Congress didn’t intend for it to be a specific remedy for the constitutional violations b/c it’s a state law tort The majority RECOGNIZED a Bivens claim because FTCA was not an “alternate remedy” it’s a waiver of sovereign immunity not a remedy to sue an agent of the government specifically; it’s not a remedy for a constitutional violation At ALL Is this consistent with Minneci v. Pollard? Notes The Court has cut back dramatically on this ^ expansion in the years since 1980 but it has not overruled Bivens; Scalia and Thomas would like to just keep Bivens, Passman, and Carlson and stop there Narrowing Bivens in 3 ways: Questioning the idea that all constitutional rights are “independent” rights Changing its view of special factors and congressional action for alternate remedies (Wilkie—Court sticking with same two factors but phrasing them differently and making them much broader) Narrowing the class of defendants who can be sued under Bivens Wilkie [THE KEY TO WHERE THE COURT IS NOW; expanding Bivens exceptions] Facts: π ranch owner who acquired the land from someone who promised the government as easement; the government never recorded the easement and now wants Wilkie to recognize it; the government intimidated him into giving it to them; he brought a Bivens action in response arguing that they violated his substantive due process right (available for land use decisions) The Court refuses to recognize a Bivens claim If an alternative process for protecting the interest amounts to a convincing reason for the Judicial Branch to refrain from providing a new and freestanding remedy in damages, and if not, use judgment that is appropriate for a common-law tribunal 5 ***This is like part 2 of the Bivens facts but it’s different because there’s nothing about congressional declaration of an alternative remedy; it isn’t focusing on whether it’s equally effective but whether it’s close enough to convince the Court that maybe it shouldn’t get involved here is there an alternative remedial process that’s a reason to not get involved ***Not whether Congress has explicitly designated an alternative remedy but whether there’s an alternative process amounting to a convincing reason (is there anything out there); Congress is capable of saying what it wants ***Second part = Special factors: Congress was better suited to evaluate the impact of a new species of litigation & tailor any remedy to that problem now it’s a broader question of looking to the factors, & whether this is a proper case that includes the special factors that might counsel hesitation ***Now focused on whether it was appropriate for the tribunal to create a new CAX (not a laundry list of special factors; may include discipline w/in the military structure) IMPLICATION This case built on Bivens for reasons to not allow someone to sue under it The Court said there are remedial processes here that could vindicate virtually every injury he suffered APA remedy for agency overreaching; trespass claim; conversion claim for cattle—none is a single freestanding claim that would get at everything that’s going on; the Court punts on the issue: BECAUSE there’s a special factor—the difficulty of defining a CAX; the government can ask for an easement every single day from you—there’s a fuzzy line to when it gives you a claim, therefore, Congress is more suited to evaluate the impact of this species of litigation The Court doesn’t consider whether there’s an independent federal interest; they aren’t denying there’s a constitutional claim; just saying it’s too fuzzy NOW, it’s more of a balancing test of whether the Court should get involved; it eliminates the presumption that Bivens is available Exactly as far as we’ve gone and no further Narrowing the Class of ∆'s [another means of limited Bivens] Generally, limiting it only individual ∆'s, not an entity Claims only lie against individuals, not agencies FDIC v. Meyer Federal agencies not amendable to suit under Bivens; we can only sue the individual officer(s) who are responsible for the violation Claims do not lie against private entities (corporations) Malesko Bivens action could not lie against a private prison corporation ***The court purpose of Bivens is to deter individual wrongdoing Allowing claims against entity would direct everyone’s attention there b/c of their deep pockets; there is less jury sympathy & it would detract from Bivens’ core purpose The predominant view was that private prisons are state/government actors because corrections is a public function; if the private prison is responsible for a constitutional violation, can one sue that private prison? This court said NO The Court also held that the π is NOT w/out remedies Bureau of prison had remedial processes Tort suit in state law ***HUGE jump b/c this is the first time the court is looking at what state law does; the prior cases have all looked at congressional action & the general remedial processes available in the federal system [first time state tort relief could be a reason against allowing Bivens] The fact that state law remedies provide roughly similar incentives for ∆'s to comply w/ the 8th Am while also providing roughly similar compensation to victims of violations DISSENT: the only question in looking to alternate remedies should be what’s federally available Minneci v. Pollard (SCOTUS) π suing private individuals of the prison for violation of 8th Amendment in refusal to provide medical care; the court wouldn’t recognize a Bivens act, using the Wilkie alternate remedies prong, deciding that the availability of tort relief to an individual suing a private individual who acted under color of federal law was a reason for precluding Bivens; federal officials would normally have immunity under FTCA, here, they weren’t actually federal employees so they could be sued in tort Where a federal prisoner seeks damages from privately employed personnel working at a privately operated federal prison, where the conduct allegedly amounts to a violation of the 8 th Amendment, and 6 where that conduct is of a kind that typically falls within the scope of traditional state tort law, the prisoner must seek a remedy under state tort law This case BROADENS the idea of ALTERNATIVE REMEDIES This was the last Supreme Court case on the Bivens issue ***SINCE Minneci, 7th Circuit allowed claim against FBI agent who framed the π, violating Brady for failure to reveal exculpatory information—no alternative remedy for the DP violation (habeas didn’t provide compensation) and defendant couldn’t provide special factors counseling hesitation it’s significant that this came out of the 7th Circuit because it isn’t particularly liberal 7th Circuit wouldn’t allow a Bivens action against Rumsfeld for interrogations of military contractors; the interrogation cases have failed because the court doesn’t want to get involved to figure out what is proper foreign policy to combat the issues Interrelationship between Bivens and 1983 Two ways they’re interrelated Bivens is the rough federal analogue to § 1983 and precedent is generally interchangeable when its on an issue the 2 have in common (see note 11, p. 26) As Congress cuts back on § 1983, the question comes up whether anybody can somehow get around that retraction by bringing Bivens (can you make an end-run on § 1983 with Bivens) Example 1978, Bivens on books but court hadn’t overruled 2nd part of Monroe, so you can’t sue municipalities; want to sue city of Memphis but can’t under § 1983 Options Sue under state provision Sue under generic tort claim If you want federal jurisdiction for a constitutional violation, can you bring a Bivens action? You’d argue the court should imply a cause of action under the 14th Amendment BUT the defendant is going to say that the presence of § 1983 is an alternative remedy (but Monroe eliminated this possibility) Congress has spoken on this issue: § 1983 is STILL the alternative because it’s the remedy Congress designed to handle this field; you don’t need the exact same relief; it’s enough that there’s some remedy in the field that you could use (Jett) Jett: Plaintiffs cannnot avoid the limits of the reach of § 1983 by asserting Bivens claims; the doctrine of respondeat superior for a municipality is not available for Bivens One can’t use Bivens as an end-run on § 1983 (didn’t explicitly reach this issue but in dicta it approved of the circuits’ idea that § 1983 is what’s out there) What if Congress were to repeal § 1983? Unanswered question; you could then say there needs to be some remedy and bring a Bivens action; is there ever some guaranteed remedy? This would become an issue if Congress tried to preclude any remedy for violation The Prima Facie Case [2 parts—(1) under color of state law and (2) violation of constitutional or statutory right] Generally 2 elements Conduct complained of was committed by a person acting under color of state law Goes to the permissible defendant (couldn’t bring 1983 action in Bivens because it was a federal agent acting under federal law) Monroe didn’t resolve whether persons who are NOT government employees but who receive power from the government, act under state law If satisfying state action, the satisfying this prong (Lugar) but not vice versa Conduct deprived a person of rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution or federal statutory laws of the United States Statutory claims are a minor subset of § 1983 actions For the most part, it deals w/ constitutional violations To make out a constitutional violation, in most cases you’ll need to show state action b/c only the state can violate the Constitution in some instances State Action/Action “Under Color of Law” Lugar v. Edmondson Oil Co., Inc. (U.S. 1982)—facts: D attached P’s property to secure debt; it sought prejudgment attachment, clerk issued the writ, and it was executed by the sheriff; later it was determined that defendant didn’t satisfy 7 statutory requirements to attach P’s property in the first place; P brought 1983 action alleging DP violation with joint participation with state officials; the Court found Edmondson to be engaged in action under color and in state action (joint participation) Overview Interrelationship between state action and under color of state law they are often the same in practice and are always interrelated; if conduct IS state action, it’s ALSO under color (if a defendant is a state actor, he is also acting under color of state law BUT the converse may not be true); the under color is a broader concept and subsumes state action finding state action kills 2 birds with 1 stone Important case It speaks in detail about the relationship b/w state action & under color (Powell’s dissent important b/c he thinks it’s not a state action case) As a state action case b/c it spells out the method of the state action inquiry for a narrow set of cases AND provides a general framework for the state action inquiry which codifies prior state action cases; it’s the general framework the court uses for most state action cases Rules For actions brought against a state official, state action & under color inquiries are identical (fn. 18—under color is not always state action, “w/ knowledge of & pursuant to that statute”) If you’re suing a state official who’s exercising state power (Monroe) the 2 concepts of state action & under color are identical b/c the state official who’s exercising state power is a state actor & is acting under color of state law If the person is a private individual, the SAME is true ex. Just an individual who doesn’t like who you’re voting for & they beat you up to put you in the hospital; the person isn’t violating your constitutional right if they’re acting ALONE; BUT in the case of joint action (private person acting jointly w/ state to accomplish something), the state is engaged in station action but what about the private person? MAYBE Constitutional requirements of DP apply to attachment, thus government action will be required in order to allege a violation of attachment rules State action is an appropriate inquiry to start with Is there state action? 2-part test (see below) Analysis for STATE ACTION: 2-part test FIRST INQUIRY: The deprivation is caused by an exercise of some right or privilege created by the state or by a rule of conduct imposed by the state or by a person for whom the state is responsible (the origin of the right/ability to act; whether the person is getting authority to do what he does from state law) Whether conduct is attributable to the state; whether it was a right created by the state here, the process of attachment COULD be ascribed to the state b/c the government allowed this process To say that D’s conduct was unlawful means that he went in contravention of the state statute & thus the conduct CANNOT be attributed to the state; thus as a private actor, dissimilar to the facts in Monroe, D cannot be liable under § 1983 HE must allege that the state statute is DEFECTIVE & that the private party acted under the authority of it Ex.If the complaint says Edmondson unlawfully invoked the statute b/c he knew there was no basis for attached, you fail prong 1 b/c= you can’t attribute the action to state law b/c you’re violating state law (not under color of as state actor b/c not doing something attributable to the state) HERE, he was acting within the confines of the law Moose Lodge: liquor licensing claim; the Supreme Court found that the lodge’s refusal to serve was not state action or attributable to the state b/c there was no state rule & state hadn’t done anything to encourage discrimination SECOND INQUIRY: The party charged w/ deprivation must be a person who may be fairly said to be a state actor (is, acted together, or obtained aid, or otherwise chargeable) Whether private parties may be appropriately characterized as “state actors” The Court imports all pre-existing state action law (public function, state compulsion, nexus, joint action) AND then says there’s something special going on w/ prejudgment attachment cases but doesn’t call any prior law into question 8 Flagg Bros.: warehouse owner selling goods if doesn’t pay pursuant to NY UCC; the Court held there was no basis for calling the warehouse a state actor b/c the sale was independent of the state (no petition to the court or sheriff’s help); this failed the second prong HERE, there was joint participation with prejudgment attachment! ***The two questions collapse into each other when you’re dealing w/ a state official but they diverge when the claim is directed against a person without such apparent authority, such as a private party A private party’s joint participation w/ officials in seizure of disputed property is sufficient to characterize that party as a state actor for the purposes of the 14th Am.; thus, he was acting under color To act under color, the party does not have to be an officer of the state but MUST be acting jointly w/ an officer of the state (invoking aid is sufficient where the state created a system like the one here) SUMMARY Rule of conduct from the state Fairly said to be state actor (public function, compulsion, nexus, prejudgment joint participation) HERE: to the extent that a private party acts together w/ the state to seize someone else’s property to execute a prejudgment attachment, that the party is engaged in state action b/c the rule of conduct comes from the state AND in this context of prejudgment attachment, the joint participation is enough to fairly call the party a state actor Dissent This was a presumptively valid statute, thus it’s unfair to hold private parties liable for statutes later deemed unconstitutional FN. 23: this only applies to prejudgment attachment There may be limits—sometimes a private person’s working w/ the state makes that person a state actor w/o saying that every time someone calls the cops that they are magically a state actor Also, the majority recognizes the potential unfairness of this but there’s always an affirmative GOOD FAITH defense Should use the conspiracy analysis (which didn’t exist here) Majority was relying on Adickes, which was an under color case not state action Joint participation issues are usually “under color” cases and that was the case in Adickes it was a private party invoking state aid to accomplish private purposes BUT he thinks this is different from Adickes b/c there was a conspiracy claim there but here, there wasn’t thus it shouldn’t be considered under color here 1983 is supposed to prevent people from using the cloak of authority to do unconstitutional things; HERE, there was an exercise of a valid legal process It was private action—filing the lawsuit; the lower court agreed with this analysis but the SUPREME COURT determined the company was a proper defendant Notes on Lugar It’s not clear whether Lugar is limited to prejudgment procedures BUT, the court now uses the Lugar two-prong approach for state action cases; at first, the courts were unclear as to whether to use Lugar (generally or just in prejudgment attachment cases; where the law spells out a procedure to get someone else’s property as some component of a larger dispute and the private party is working jointly w/ the sheriff or other state official to do that) There is a line-drawing issue—and the courts have limited it to attachment and garnishment cases This could come up in eviction cases when someone doesn’t pay rent; give notice and then you can evict them; the landlord can put the stuff on the street; but if the landlord calls the sheriff to take your stuff and put it on the street, then it’s similar to Lugar; lower courts have invoked Lugar in evictions cases even though it’s not “attachment” In Edmondson, the court held that discriminatory peremptory challenges by a private litigant are subject to § 1983 under Lugar, the private party was engaged in state action—rule of law comes from the federal government (law of right to exercise peremptory challenges) and the litigant can fairly be said to be a state actor; the court really relied on the PUBLIC FUNCTION (jury members = public body) idea instead of the joint participation idea and also relying on the SYMBIOTIC RELATIONSHIP idea that the government has put its power and prestige behind the private party by excusing the juror the court uses the 2-prong approach but does not invoke this special test, but uses an amalgam of a couple of them Without the availability of the preemptory challenge the selection of jurors would be total state action McCollum (criminal defendants) 9 ***NOTE: many have suggested that the court is more willing to find state action when race is involved (it is empirically true) American Manufacturers: private company regulated by a federal agency in giving benefits to its employees was NOT a state actor; it was a DP case that looks like Lugar; PA allowed a party who doesn’t pay worker’s compensation to withhold payments and call a hearing to determine whether the person was really due the payments; invocation of the state agency w/ private parties to conduct a REVIEW; the private party is arguing that withholding is state action, losing property w/o DP; the SECOND PRONG was not met no public function and state didn’t compel/encourage the withholding Private decisions to withhold payment and seek utilization review are not fairly attributable to the state REGULATION does not make the party a state actor Brentwood: the most recent Supreme Court case doesn’t mention Lugar but it remains the general approach Overview of State Action Law A traditional state action inquiry comes into play when a party argues that private action is the state’s one can make an end-run on this inquiry by showing that the seemingly private party is the state Why important? Most 1983 cases involve constitutional claims that require state action as a prerequisite to finding a violation AND Lugar held that it kills 2 birds with 1 stone Problem: state-action very fact-based and open-ended 2-prong test from Lugar, 2nd prong incorporates traditional state action case law History Origin of modern state action inquiry in the late 1960s, in early Civil Right era where states had law on the books that required racial segregation in places of public accommodation; the states in the South would mandate segregation ex. dining facilities with sit-ins and owners calling the cops; cops would arrest for trespass; issue: whether that eviction was state action, attributable to the state (whether the shop owner violated EP) The Court general said the state couldn’t prosecute those individuals for trespass b/c the state was responsible for the cops having been called in the first place b/c the shop owner was acting under the mandate of state law ***Same result if the shop owner actually wanted to serve African-Americans but couldn’t under state law; still acting discriminatorily because the state is telling him to Pervasive Entwinement describing the person AS THE STATE = end-run around the traditional state-action inquiry Lebron [PERVASIVE ENTWINEMENT] Renting billboard critical of Coors; Amtrak wouldn’t let them show this advertisement b/c it was political; the Court held this was a violation of the 1st Am. by Amtrak Supreme Court said that Amtrak is required to follow the First Amendment b/c it IS THE GOVERNMENT; it’s a corporation that the federal government created for a specific purpose that the federal government funds and the board of which it appoints; it is an agency of the government, not a private person thus the Court doesn’t even need to worry about the state action analysis Just calling something “private” doesn’t mean it really is; if the government creates it, funds it, and makes decisions for it, then it is the government Brentwood Academy v. TN Secondary School Athletic Ass’n (2001) Private school accused of engaging in recruiting violations; the school said that the rules violated the 1 st and 14th Am. (speech and due process); TSSAA argued they were private (w/ reps from public and private schools) that make the decisions, so there’s no state action; the Supreme Court held that the association ITSELF WAS THE STATE; the state defines the group, the employees were members of the state pension fund; lots of state officials who were involved in sitting in the meetings even if they couldn’t vote and the principals of the schools made up 84% of the members Association’s regulation made it a state actor due to pervasive entwinement with the state school officials in the structure of the association It’s a fact-based inquiry—looking for any reason to not call it a state actor Horvath State actor because the legislature created the library to serve a governmental interest, the town appointed ½ of the trustees, and the library’s funding came from the town 10 If a nominally private entity really isn’t private but is a creation of the government, that the government is pervasively entwined with, then there’s a good argument that it IS THE GOVERNMENT and don’t need to use public function or state action analysis Public Function A function that is traditionally, exclusively performed by the state and not to the function in the abstract but whether the person is exercising the power that the state has delegated (West v. Atkins) 2 inquiries in the rule: the traditional, exclusive inquiry and whether the state has delegated it to that party Whether it was inherently a governmental function historically Policy: don’t want the state to be able to delegate its functions so as to get around constitutional requirements Ex. education, if ALL delegated away Ex. security guards ≠ state actors because state still has its own police If the city decided to privatize its entire police force/education system then they cannot violate the Constitution NOW, public function seems to be just ONE FACTOR the court uses in determining the broader state action question Cases Marsh v. AL: company town = state actor; wouldn’t allow Jehovah’s Witnesses to preach in violation of their First Amendment rights Jackson v. Met. Edison: utility company ≠ state actor b/c not traditionally a public function; the court looked at history and held that private companies have historically provided utility service; ***different if something like eminent domain not something the state usually got involved in and the parties had options (sue in contract) Flagg Bros.: warehouseman ≠ state actor just b/c acting pursuant to the UCC adopted by the state; this was a private-dispute resolution and not an exclusive government function; it was not the only means of resolving the dispute The court listed education, fire & police protection, and tax collection measured with a greater degree of exclusivity suggesting the things would be considered as public functions Lower courts have added: private prisons (Malekso) and running a volunteer fire department (Goldstein) BUT, you can’t take this list literally because not all education is a public function (i.e. private Christian schools; Briarcrest ≠ state actor) because the inquiry is more open-ended and fact-based inquiry into the relationship between the state and the private party and whether in essence the state has delegated or passed on that function Private Prison: big debate now; application of the 8th Amendment Richardson v. McKnight: court didn’t decide Malesko: there could be an action under § 1983 for private prisons 6th Circuit decided explicitly in Street v. CCA—if the government is delegating this historic function, the delegatee has to meet constitutional standards Goldstein: volunteer fire department = state actor West v. Atkins: city couldn’t privatize its entire school system so as to get around constitutional requirements MIM example: city gives MIM some funding for their cost; city benefits from MIM from sales of beer, tourism, and city publicity; city leases large part of downtown to the MIM and blocks off the street; dispute over 1st Am. protestor who was outside the actual area that you need to have a ticket; officer had him removed; whether it was state action Public function: allowing a private group to run a public area; policing inside of it as traditionally for the state; but it may be no different than letting a little league use a playground; also problematic is that the MIM officials did not actually arrest the dude, take him into custody, or remove him; they just CALLED a police officer (cuts against public function b/c the state is still performing the public function) Joint participation: policing but Lugar may be limited to attachment COURTS’ ANALYSIS District Court: found state action 6th Circuit: did not find state action—no public function because the actual cops were policing the area; different from Faneuil Hall (see below); distinguishable from public property 11 Faneuil Hall: the hall leased to a corporation for the whole year to totally run the area; no way to tell where the public street ends and the private place begins; plaintiffs were protesting the sale of veal and they were kicked out; the security guards forcibly removed them NOT calling the cops; the court found state action w/ public function because the city basically delegated running part of downtown Boston to a private group and policing of that area to the private company it looked LIKE and was NEAR a public area Gateway: church group picketing outside stadium for use of word “Indian”; guard of sports complex removed them; the court found state action b/c there was no way to tell where the city streets ended and the sports complex began and there was a delegation of policing Symbiosis Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority: coffee shop located on property of municipal parking garage; it paid rent to the city and the city used that money to fund its parking garage; court held it was a state actor when it violated the constitutional rights of an Af-Am whom it refused service on account of his race State sought operation of the coffee shop so it could get around its debt, and thus the court found a symbiotic relationship between the two; they were interdependent (the court doesn’t actually say “symbiosis”) the coffee shop’s getting customers from location & signage and city being able to keep garage going and pay debt because it was getting rent Not only that but the state put its power, prestige, and property behind discrimination; it was feeding off the profits of private wrongdoing San Fran. v. U.S. Olympic Co.: the city of San Francisco wanted to host a gay Olympics and the USOC would not allow them to do so; the court held that the USOC was NOT a state actor; the government can subsidize private entities without assuming constitutional responsibility for their actions; the government did not coerce or encourage the USOC in the exercise of its right; DISSENT: they represent the nation to the world (public function); they confer mutual benefits (symbiosis) Many argued this was indistinguishable from Burton; the USOC had exclusive control over word “Olympic” and controlled people who could get licenses; the government created it, subsidized it, and made money from it, so the government arguably profited from its discrimination because the USOC is denying the license for fear that it would be bad for the USOC ***it only wants those associations that will bring in $$$ BUT, the court held that the government was ENCOURAGING it, it was just TOLERATING it Dissent: there was government action: (1) public function of country’s athletic representation to the world (not just amateur); it’s diplomacy; (2) profiting from discrimination (Burton) American Manufacturers’: Burton approach was an early state action case containing vague language; it narrowed this ***There are still lower courts that use symbiosis to find state action MIM case: economic benefits to the city and city WANTS a lot of beer to be sold; they want attendance; by getting the religious dude out of there more people will buy beer OR you could argue that it wasn’t really benefitting because it just wanted anyone to get out of the way (not getting him out of there BECAUSE of his message); 6th Circuit didn’t find symbiotic relationship; not like Faneuil—Boston benefitting from having a gentrified, tourist-friendly area that it didn’t need to police; to the extent there weren’t protests, more people would come out Government Enforcement Generally Looking @ points of contact between the state and the challenged action; looking for the government either COMPELLING private action or in other ways being RESPONSIBLE for or SHARING in the private action It’s also called the “nexus approach” (or compulsion/enforcement) Shelley: judicial enforcement of a private racially discriminatory covenant; the TWO private parties WANTED to sell the property and buy the property but the court’s ruling PREVENTED them from doing this (there was already a contract); but the court essentially violated EP by enforcing this racially restrictive private covenant; it put its weight behind the discrimination, thus making it attributable to the state Judicial action is not immunized from the operation of the Fourteenth Amendment simply because it is taken pursuant to the state’s common-law policy It is not a case in which the state has abstained from acting but has put its power and prestige behind the discrimination 12 FUTURE IMPACT: one could read the holding very narrowly or broadly, either (1) the fact that the state is actually enforcing a discriminatory agreement IS state action, so that when the state gets behind and enforces the contract, it means that the contract has to meet constitutional requirement OR (2) not about enforcing the contract but the idea that the parties have entered into a valid contract and the state is now intervening at the behest of the outsiders and saying NO you can’t enforce your contract or maybe there’s (3) compulsion Bell v. Maryland: lunch counter owner wouldn’t serve African Americans; it was custom to do this but not state mandated; students sought service, wouldn’t leave, and the owner called the cops; the cops removed them for trespassing; the issue is whether the cops are arresting engaging in discriminatory government action for arresting them for trespass; are they discriminating based on race? Or just enforcing a neutral trespass statute? It goes back to Shelley If the cops are only enforcing the statute against African Americans, the cops are engaging in a private discriminatory decision; it has to be something they could do on their own; it’s state action because it requires the state to carry it out and it has to meet constitutional standards BUT in Shelley, there was a willing buyer & seller and BUT FOR the active intervention of the state, the contract would’ve gone through THIS case would be like Shelley if the shop owner is serving the African Americans and the patrons call the cops and the cops disallow the owner from serving the African Americans it is the compulsion that’s the KEY Ultimately, the Supreme Court decided this on a different theory; there’s one opinion that says it’s like Shelley and one that it’s not Government Approval/Encouragement ***There is a spectrum of neutral approval/acquiescence and enforcement/compulsion Reitman: Private landlords violating constitutional rights when refusing to rent apartments based on race; the constitutional provision allowed landlords to have absolute discretion in refusing to rent their property; constitutional provision giving a right to discrimination involves the state in discrimination; courts have backed off—modern cases require that the state put its weight behind discrimination, that it COMPEL or SIGNIFICANTLY ENCOURAGE it Here, the court held that the provision encouraged and significantly involved private racial discrimination Peterson: the arrest and trespass claim is the responsibility of the state when the law is on the books Jackson: public statement by sheriff not permitting blacks to desegregate restaurants after hearing that there was going to be a large-scale demonstration lead the court to treat the city as though it actually adopted an ordinance forbidding desegregated service in restaurants This case takes it further; there’s no law on the books BUT there’s practice the court held that it had coercive potential, i.e. you’re going to be in trouble if you don’t do what the custom is; the state was strongly encouraging it Court emphasizes, “sufficiently close nexus between state and challenged action so that the action of the latter may be fairly treated as the state”; that approval of a request when the state hasn’t put its weight behind it by ordering it does not make it state action; it came from its own initiative, not the states Moose Lodge: Lodge refusing to serve blacks; had a liquor license from the state under which it could operate; the court held it was not a state actor because the state didn’t encourage it The argument was that the state regulated it because it gave it a license BUT the state didn’t compel discrimination or encourage it Exception: to the extent that the lodge’s bylaws required it to discriminate, and the state law said it had to follow the owner’s constitution, then it would be a violation The Supreme Court said that provision was unenforceable because the state would be compelling them to discriminate, as their license was dependent upon them following their discriminatory bylaws Shelley parallel to where the state would take their license away if they WEREN’T discriminating; if the state is stepping in and saying you must even if you don’t want to, then it becomes the decision of the state MIM: the private group made the choice and the police were just enforcing the decision; there was no compulsion or encouragement Jackson v. Metro. Edison Co.: the court held that a utility company was not a state actor even though it was a monopoly, heavily regulated, and the commission approved of its right to discontinue service 13 A business subject to regulation does not convert its action into state action even if the regulation is extensive and detailed The inquiry must be whether there is a sufficiently close nexus between the state and the challenged action of the regulated entity so that the action of the latter may fairly be treated as that of the state itself here, the state didn’t put its weight behind the decision Flagg Bros.: the state’s adoption of the UCC didn’t render the states to have encouraged the procedure Dissent: the constitutional defect in these creditor-debtor cases is the lack of state control over the private action Blum v. Yaretsky: discharge and transfer of patients receiving Medicaid without notice or opportunity for a hearing; the state responded to the decision by changing the Medicaid benefits; the court held it was not state action because the decision originated in the private entity and the regulation wasn’t enough; there was no significant encouragement or coercive power but mere acquiescence The state is only responsible for a private decision where it has given coercive power or significant encouragement, overt or covert MIM: no way to argue that the choice to exclude the dude was that of the city of Memphis Rendell-Baker v. Kohn: non-profit school receiving funds from state; state picked the students for the program; the school fired a teacher, and she claimed it was a violation of EP; the court held that the school’s PERSONNEL policies were not state action; the regulation wasn’t related to personnel decisions and the state didn’t have an interest in those decisions The Spectrum: ACQUIESCE (most of moose)---REGULATION---ENFORCEMENT (shelly broad view)---ENCOURAGING (reitman)---Significant Encouragement (Jackson and Blum) --- COMPULSION (shelly narrow view and moose by law part) The Court has climed back up the spectrum. Seems to have rejected Symbotic Approach. What about Luger? Seems to be no state action under any of these approaches… American Mfgs. and Lower courts read it as only applying as a special analysis to prejudgment attachment cases. Under Color of Law Generally Still need to look at the under color analysis when the private party is not engaged in state action or a state actor within the traditional analysis Powell in Lugar: thinks it should’ve been an under color case (no public function; no delegation; no state benefit; no compulsion or strong encouragement), instead the state permitted a course of action (like Flagg); the court found state action in Lugar by announcing a special rule that joint participation constituted state action for prejudgment/attachment cases Powell points out that the majority relied on Adickes, an under color case with private party engaged in joint action with the state; the question should be whether the private party acted under color of law by virtue of the agreement and joint participation with the state ***The hallmark of under color cases is joint participation (private party who enlists state aid or otherwise acts jointly with the state to accomplish some sort of end); it goes back to Monroe, where the Court said that a person who acts under a mantle of state authority acts under color (“misuse of power possessed by virtue of state law and made possible …” ISSUE: what sort of joint action do you need in order to show that the private party is acting under color? Adickes (U.S. 1970) Facts: Kress, owner of restaurant, refused to serve white woman because she was with black students; he called the police and they arrested her for vagrancy; Kress asserted a right under the MS statute to “choose customers by refusing service”; the woman alleged it was a violation of EP under the 14th Amendment for discrimination on the basis of race; she sued Kress under § 1983, deeming him under 1983 for two different reasons (1) conspiracy/joint participation and (2) custom The district court required her to show that the custom of segregating races was enforced by the state The court of appeals required her to show the custom was state-wide the Supreme Court disagreed with this RULES 14 Re: conspiracy w/ state official & private person here, Adickes is arguing that Kress is liable because he acted JOINTLY with the police in refusing to serve her and in having her arrested [re: under color] The Court held she could prevail if she can prove that a Kress employee, during the course of employment, and a Hattiesburg policeman somehow reached an understanding to deny Adickes service in the store or to cause her subsequent arrest because she was a white person with black people ***AGREEMENT suffices to ALLEGE it’s under color The involvement of the state official in the conspiracy provides state action for a violation of EP, whether or not the actions were officially authorized or lawful (Monroe) thus, a private party in a conspiracy can be held liable under § 1983 It is enough that the private party is a willful participant in joint activity with the state or its agents (Price) ***THIS satisfies the FIRST PRONG of 1983 Presence of the police in actually arresting Adickes makes the deprivation of equal rights the product of state action; Kress couldn’t arrest her himself but Kress is a proper D because he has jointly participated in the action that culminates in the deprivation of her EP rights Custom/Usage for BOTH under color & state action components Generally The claim HERE was that Kress was a proper D because he acted under color of a CUSTOM of segregation; thus the legal issue is whether custom has to have the force of law or if it can just be predominant community sentiment The Court holds that it needs to have the force of law Custom for which the violation has some legal consequence INFORMAL ACTIONS of state officials can make a custom as legally binding as a statute (“settled practices of state officials”) Further, it doesn’t just have to be a custom of not serving whites who eat with blacks; it can be just a custom of segregation Custom must have support in law or force of law; a custom or usage of a state for purposes of § 1983 must have the force of law by virtue of the persistent practices of state officials (policy of preventing— maladministration of the law and refusal to enforce laws) Relevant inquiry for custom: whether at the time of the episode in question there was a longstanding and still prevailing state-enforced custom of segregating the races in public eating places Settled practices of state officials may, by (1) imposing sanctions or (2) withholding benefits, transform private predilections into compulsory rules of behavior no less than legislative pronouncement (1) Imposing sanctions: every time the person violates the custom, they’re picked up for vagrancy; using the vagrancy law as a means to enforce the custom; show that the police subjected A to false arrest for vagrancy for the purpose of harassing and punishing her for attempting to eat with black people (2) Withholding benefits: tolerating something knowing it’s going to happen; the police would intentionally tolerate violence or threats of violence directed toward those who violated the practice of segregating the races at restaurants; this is more subtle; if Kress were known as a restaurant that served mixed parties, the private goons would threaten him, and if the cops know and they don’t do anything about it, then this would give the practice the force of custom by withholding the benefit of protection ***This gets Kress under color, but still need to show STATE ACTION for the EP violation Here, state action comes from the police having acted and the private person as a proper defendant because it acted under color of law by engaging in this joint action to accomplish the unconstitutional end the state has to have done enough so that you have state action; the private person has to have relied on the state or entered into an agreement with the state or conspired with the state to have benefitted from the state to accomplish the goal This is where we get into the idea of COMPULSION For a deprivation of EP, there must be state action State Action re: 14th Amendment claim: 15 If the state had a law requiring a private person to refuse service because of race, it is clear this would violate the 14th Amendment A state is responsible for the discriminatory act of a private party when the state, by its law, has compelled the act; a state may not use race or color as the basis for distinction—it may not do so by direct action or through the medium of others who are under state compulsion to do so ***Lombard: where the official said they wouldn’t tolerate a sit-in demonstration ***here, if the state compelled segregation in restaurants (Peterson) For state action purposes, it makes no difference whether the racially discriminatory act by the private party is compelled by a statutory provision or by a custom have the force of law Re: Custom it doesn’t have to be on the statute books; if the sheriff is compelling segregation by saying that if you don’t segregate you’re going to be shot, then you have compulsion! Dissent (Douglas): custom doesn’t have to have the force of state law; use the 13th Amendment which doesn’t require state action to show a violation; or Congress is allowed to punish people in violation of § 5 of 14 th Amendment (Guest) Concurring in part, Dissenting in part (Brennan): Agrees with the conspiracy establishing state action; but disagrees that this action was authorized/encouraged by MS’s statutes; Peterson—state commanded discriminatory result and removed decision from private realm; where state commands discrimination, it is state action whether or not the private person is motivated by the command For “under color” the person must be acting consciously pursuant to some law or in conjunction with a state official (under color is NARROWER than state action); UNDER COLOR is narrower REQUIRING KNOWLEDGE OF THE BODY OF LAW and acting consciously pursuant to that (STATE ACTION doesn’t require such knowledge) Joint Participation & Conspiracy Generally what do you need to show? Adickes A private person who engages in JOINT ACTION with state officials may act under color of law (Lugar uses this reasoning) Examples Landlord smells weed; calls police who gain entry and arrest residents assume there’s a 4th Amendment violation; there is NO joint participation because no agreement or conspiracy; merely a private party availing himself of the cops Store security guard holding person until the police arrest him we need to know more; if there’s a discriminatory police and a minority person is in the store and the guard wants to make sure the people don’t come back AND the cop knows everyone who’s stopped is a minority, then it would be a violation DUE PROCESS: if the cops don’t make their own assessment, then the guard would be acting under color but if the cop makes his own assessment, it’s just like the landlord calling the cops for noise FILLING OUT ARREST FORM: if the cop doesn’t do an independent investigation, and just hauls the person in this shows an agreement that the private person is making the judgment to arrest someone for shoplifting thus the private person is acting under color of state authority by relying on that power from the police to haul the person in. The KEY factor: if the police are acting independently in doing their jobs or whether the private party is acting pursuant to reliance on state authority Adickies requires some sort of agreement between the guards and the cops; just having 1 lazy cop fail to investigate 1 case isn’t going to be enough Skinheads beat plaintiff; police say they won’t intervene until it gets “totally out of control” Dwares: P sues both skinheads and cops; here the cops are basically giving permission for a controlled beating and encouraging it until it gets out of control; the argument: the private party is acting under color b/c it’s relying on the state permission & authority; the approval to continue doing something that normally a private person wouldn’t do with the cops watching; the court said P state a claim Media Ride-Alongs: Supreme Court held police violate 4th Amendment by bringing the media into a private home while executing a warrant; 9th Cir. held members of media also in violation 16 Dennis v. Sparks: Private party bribed a judge to issue an injunction & the judge did; the court held the private party was a proper D b/c of the joint participation with the state official (the judge) Merely resorting to courts & winning doesn’t make a party a co-conspirator or joint actor; BUT here, the allegations were that the injunction was the result of a corrupt conspiracy involving a bribe to the judge ***: You need something more than some points of contact w/ the state or enlisting the aid of the state (i.e. filing a lawsuit & winning); it is the joint agreement/conspiracy to violate rights that makes the private party a joint participant w/ the judge & thus acting under color Why not sue the judge? JUDICIAL IMMUNITY; the private parties don’t have it To get the private parties, they must have acted under color (hard to show they are state actors), so under Adickes, show that they were willful participants in joint action with the judge POWELL’S Lugar DISSENT: there shouldn’t have been action under color in that case because of Dennis; in Lugar, there was no conspiracy; that’s why the majority in Lugar had to create a special state action approach because Dennis provides that there was no action under color for just filing a petition with the court The Agreement Sixth Circuit: express agreement is not necessary nor is it necessary that each conspirator know of all the details of the illegal plan or the participants; plaintiff must show there was a single plan, that the alleged coconspirator shared in the general conspiratorial objective, and that an overt act was committed in furtherance of the conspiracy that caused the injury to the complainant Facts: people yelling at those not in the picket line; the police were there to control and so were private security guards and off-duty officers; the allegation was unconstitutional suppression of speech the claim: conversations between the private security guards and police showing an ongoing agreement between the two parties Generally, the circuits have had trouble articulating a standard to show an agreement they all generally think that you don’t need a smoking gun (an explicit conversation where they say, let’s violate the Constitution); there does need to be some willful joint action to accomplish the goal Soldal v. County of Cook (7th Cir. 1991): property owner evicting mobile home; cops there to prevent the guy from interfering w/ the eviction & TOLD HIM THAT; the court found that the P STATED A CLAIM FOR D having acted under color b/c the guy had a right to resist eviction & the cops’ statement prevented that; the court presumed a conspiracy If the cops were simply there standing by, it wouldn’t be enough to show that the cops were aiding what’s going on mere non-participatory presence is not enough Here, the cops were basically saying, we’re preventing you from exercising your legal right to intervene; here, the landowner relied on the cops being there to help in his pursuit (other ex. cops helping tow the trailer or deputizing the land owner to help them) Courts say there is a spectrum of non participation presence to active role Jones v. Gustchenritter (8th Cir. 1990): this focuses on whether the STATE ACTED; landlord wanting to evict tenant & the officer was there to prevent violence; the evictee stated he didn’t object b/c he was afraid of cops b/c one of them body cavity searched him once; the court held the officer was a state actor [enough to get it to the jury] & that there was enough E that he participated w/ the private actor in preventing the due from trying to stop eviction Similar to Soldal but the court focusing on the other part of the equation—here, there was state action w/ the mere presence of the officer; the cop isn’t telling the lessee why he’s there 2 pieces (1) showing basis for suing private individual who calls the cops & (2) to make out a DP violation, the police must’ve acted b/c the ultimate eviction would have to be the product of state action to make out the PF case The police on the job is a state actor but did he act enough so that the deprivation is the product of state action? The court held it was enough for the jury to decide Soldal & Gunschenreitter: In Soldal, the private party benefitted from the state and in Gunschenreitter, the court was looking at whether there was more than a neutral police presence; there’s a spectrum of police presence Ex. Repossession w/ private person taking the car; it’s not state action even if the state says you can repossess cars BUT if the repo man calls the cop & asks for help and the cop hooks up the car, then there’s joint action (the problem is the PURPOSE of the cop being there—if just to prevent violence, not state action; if intimidating or stating unconstitutional purpose, then perhaps it’s enough) NCAA v. Tarkanian (1988): MIRROR IMAGE CASE; coach sued NCAA for firing him by forcing the college to do so; NCAA thought UNLV was violating rules so they tell them it has to suspend its coach; the court held that 17 there was no state action b/c the 2 parties were adverse; there was no joint participation & no improper agreement; this is a state action case NCAA: whether state actor and/or acting under color = the same thing in this case; BUT it’s not a proper D b/c it was adversary & an agent of the members; not like Dennis where there was a willing conspiracy (dissent: the inquiry is whether the parties act not whether they wanted to) UNLV: is a state actor b/c it’s a state institution; the actual suspension is the product of state action Mirror image: here, the private party is compelling the state to act; the Court says that the private party who compels the state to act does not constitute JOINT ACTION for under color/state action; compliance didn’t turn NCAA into state action Summary Private party doesn’t become the state by pressuring the state State’s adversary is not acting under state law EXAMPLE (Harvey): Restraining order kicked H out of apartment; H’s lawyer sends letters that H wants to go back & get stuff; W didn’t get the letter; H brings cop to let him in; cop tells landlady to open the door; H goes in and takes stuff while cop checks off the list; W claims H took more than his stuff; W argues it was a 4th Am. violation—nonconsensual, warrantless entry into the apartment; she sues the cop and the landlady under 1983 The cop acted he told the landlady to let them in; actively responsible for getting the door open; he’s helping H by checking off the list; cop engaged in state action by opening the door The landlady she’s not a willful participant here; she didn’t call the cops & didn’t want to open the apartment; she is NOT acting under color K thinks this is WRONG; she’s a state actor b/c the state’s responsible for the act; it’s like Lugar—if the person is following a state command, they are a state actor; it doesn’t mean they have to pay damages; they may have a GF defense thus if opening the door is state action, it’s also under color EXAMPLE: Law school security guard and officer at front desk; if officer were to follow you out to your car and forcibly search your belongings for no reason, that’s a 4th Amendment violation; if the guard independently goes out and does the same thing, there’s NO 1983 claim (just a private party that hasn’t been delegated a police function) If the officer tells the guard to do this and the guard does, then the guard is following state direction; it’s attributable to the state Under Harvey, then if the guard is not a willful participant, then it isn’t attributable to the state Custom or Usage Abortions: harassment of & physical harm to women entering into abortion clinics; they also appeared to be tied to a bombing of the clinic; can Adickes help find custom/color of state law If the police know the protestors are physically assaulting women or damaging the facility & doing nothing about it, then they’ve crossed the line and perhaps fall within Adickes Williams v. Payne: survival @ SJ against private hospital for unconstitutional municipal policy of obtaining E by the DOCTOR unconstitutionally by pumping suspects’ stomachs needed to offer E of (1) state officials maintaining this unconstitutional policy & (2) that the private party acted in accordance w/ it This is a violation of the 4th Amendment The court said the P stated a claim the doctor would want to argue that he made an independent assessment; the P would want to argue that the doctor was merely following orders of the police so that the doctor would be deemed to be acting under color of the dictate from the police ***If the doctor made an independent judgment, there’s NO action under color If the doctor didn’t then there’s action under color b/c the officers are using the doctor to accomplish what they couldn’t on their own You could view this as a conspiracy/joint participation case more easily than custom Congressional Power: Custom for Brennan & Douglas (dissent Adickes)—would’ve construed it more broadly, i.e. “unwritten commitment by which men live and arrange their lives” Does Congress have the power to reach such private action pursuant to § 5 of the 14th Amendment? United States v. Guest (1966): found the power to reach private action by Congress in legislating pursuant to § 5 of the 14th Amendment; § 5: Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article 18 Facts—individuals sued for interfering with African Americans’ access to public transportation by making false reports that they committed criminal acts; § 241 punished conspiracies to injure any citizen in the free exercise of constitutional rights Issue—whether private individuals could be prosecuted for this & whether Congress had the power to enact the statute; the Court held that it must find STATE ACTION for the 14th Am. violations but the state agents’ active connivance in filing false reports constituted state action; 6 justices believed they could prosecute private actors, finding support in § 5 of the 14th Am. RULE: § 5 authorizes Congress to make laws that are REASONABLY NECESSARY to protect a right created by & arising under that Amendment, thus this can reach private conspiracies; Congress has the authority to fashion remedies to achieve political & civil equality for all citizens Kimel—restricting Congress’ power under § 5; Congress cannot under § 5 make states subject to ADEA b/c it didn’t bear the requisite congruence & proportionality to any unconstitutional state action Morrison—Congress can only use § 5 to limit state action; violence against women act; Supreme Court said Congress couldn’t do this under § 5 because it lacked power under the commerce clause and § 5 of the 14th Amendment b/c the ACT was PRIVATE (not state action); Morrison’s view of Congress’ powers means that a broad reading of custom or usage to reach PURELY PRIVATE ACTION would raise serious constitutional concerns Public Employees and “Under Color” Generally We’ve been assuming that if someone is in uniform on the job, hired by the state to do the job & is doing it, the person is a state actor! Exceptions to the time when person is on the job but not acting under color Polk Personal motivation Then off-duty people (what a cop does at home not acting under duty, like spanking his child for discipline, not violating the child’s DP rights) either under color or not Where the state employee acting w/in the scope of employment BUT not acting for the state: Polk County (U.S. 1981): Do public employees always act under color of law? Here, there was a public defender; the client argued that the PD didn’t represent him properly & violated his constitutional rights; he sued the PD under § 1983; assume there’s a constitutional violation; the Court held that it did not act under color of law Classic: A person acts under color when exercising power possessed by virtue of state law & made possible only b/c the wrongdoer is clothed w/ the authority of state law; this involved an Offender Advocate The Court held that their relationship became identical to that existing b/w any other lawyer and client; it was adversarial to the state & serving the public NOT by acting on behalf of the state Adversary to the state—opposing motions; trying to keep someone out of jail when the state is trying to put them in jail Similar to normal lawyer-client relationship: subject to rules of PR PR rules: not subject to administration; doesn’t have an administrative superior but a person who is making independent professional decisions O’Connor & Estelle: where physicians in state hospitals act under color of law; the Court distinguished it from a public defender b/c a PD has adversarial functions. Working w/ the state's mission. A defense lawyer is not a servant of an administrative superior; his is subject to PR canons DISSENT: PD’s power is possessed by virtue of state’s selection of the attorney & his official employment; the physician has ethical rules, too; the PD is getting paid by the state; the state determines her budget NOTE: the Court doesn’t say that PDs are NEVER state actors they are when making hiring/firing decisions on behalf of the state or while performing administrative & possibly investigate functions Notes on Polk County Not never state actors (see above) Polk didn’t disturb cases that found PDs as state actors when acting as administrators, making hiring/firing decisions, serving administrative & investigatory decisions, or when using the position to extort payments (using the state power to extort) Conspiracy of PD with judge: Adickes/Dennis any private person who conspires w/ a judge is a proper D b/c that person is acting under color of law b/c of joint participation here, it would depend on the person’s function(?) 19 McCollum: private defense attorneys = state actors when exercising peremptory challenges; the court said whether the attorney is a state actor “depends on the nature & context of the function he’s performing”; peremptory challenges allow the attorney to choose a quintessential governmental body Speedy Trial: PD’s delay was NOT attributable to the state Reach of Polk: Whether the Court would also find that other state-employed professionals bound by ethical canons did not act under color of law; this is an issue; but do we focus on the professional canon or adversariness; West is the counter to Polk West v. Adkins (U.S. 1988) Facts: Here there was a physician under K w/ the state to provide medical services to inmates at a state-prison hospital; in this case, the physician wouldn’t schedule a necessary surgery & failed to fully treat the prisoner’s injury; the prisoner sued the doctor under 1983, claiming he acted under color in violating his 8th Am. rights to medical treatment; the Court held the doctor did act under color of state law (“respondent, as a physician employed by NC to provide medical services to state prison inmates, acted under color of state law for purposes of § 1983 when undertaking his duties in treating petitioner’s injuries”) RULES Under color traditional definition: defendant exercised power possessed by virtue of state law and made possible only because the wrongdoer is clothed with the authority of state law State action definition: deprivation caused by the exercise of some right or privilege created by the state or by a person for whom the state is responsible and the party charged must be fairly said to be a state actor State employment is generally sufficient to = state actor Under color: when D abuses position given to him Physicians analysis: The ethical obligations don’t conflict with state authority defendants are not removed from the purview of § 1983 simply because they are professionals acting in accordance with professional discretion and judgment Contracting out medical care doesn’t relieve the state of its constitutional duty to provide adequate medical treatment to those in custody and doesn’t deprive prisoners of 8th Amendment rights ***The state had an obligation to provide adequate medical care to prisoners; the doctor ASSUMED this obligation; if the doctor didn’t, then the state could get around the 8 th Am. by just hiring people & delegating that duty this goes back to public function analysis It is the physician’s FUNCTION in the state system, not the precise terms of his employment, that determines whether his actions can fairly be attributed to the state The fact that he was part-time didn’t matter ***It is not that someone who makes independent professional decisions is not acting under color; the key to the case is the function w/in the state system & the adversarial relationship b/w the PD & the state Here, the doctor wasn’t the state’s adversary in any way (“professional & ethical obligation to make independent medical judgments did not set him in conflict with the state”) BUT, people contracting w/ the state don’t necessarily become state actors Rendell-Baker v. Kohn: the school provided education for maladjusted young people who the city referred to them; the school fired the teacher; the court explained that almost all students were paid for by the state, the school granted diplomas, & worked closely w/ the state to provide education; but here, there was nothing from the state that dealt w/ employment, so the state wasn’t in any way telling the school how to run its business the school was like any other private contractor (the fact that a private contractor gets most of its business from the state doesn’t mean it’s acting for the state) ***Would it be different if it were a student who filed a claim that he didn’t get adequate treatment? The school probably wouldn’t be a state actor b/c the state isn’t obligated to provide education this is the KEY DIFFERENCE; the state isn’t contracting away its constitutional obligations Lemoine v. New Horizons: juvenile custody facility, like a prison, where the kid died when his punishment for acting up was hard labor; the court said the center acted for the state b/c the kid was in custody; it was the same idea as West that the state has an obligation to care for people in its custody Leshko: court held that children placed w/ abusive foster parents can’t bring 1983 suits against the foster parents; the foster parents aren’t state actors even though the state is paying them b/c they aren’t performing a constitutionally required function the state has delegated; a person who takes 20 money from the state to provide foster care doesn’t become a state actor by virtue of that receipt of payment Notes on West How to distinguish West & Polk looking for whether it’s more like the PD or more like the doctor (looking @ adversariness) Court-appointed attorney in civil rights suit: Still Polk because it’s adversarial State-appointed capital defense attorney: Clearly like Polk GAL in child protective proceeding: It could be adversary but courts tend to find that the GAL fits within Polk because they are independent and well may be the state’s adversary; they aren’t helping a specific mission (i.e. to terminate rights) When physicians perform strip searches more like West b/c the person is doing the search not really for medical reasons to save the person but because the cops say they have to do it; the doctor isn’t exercising independent medical judgment; “using professional tools to do the state’s job for it” Personal Motivation & Off-Duty Employees When personal motivation makes a state employee w/in scope of job not a state actor Engaging in misconduct that is personally motivated or that takes place during off-duty hours Ex. Cop in uniform at station; sister in law comes in and they get into a fight; the police chief punches her in the face; she brings a 1983 suit against him; assume there’s a 4th Am. violation Police’s argument: this has nothing to do with his job other than she knew where to find him; she’s not in custody; he punches her for personal reasons, so it’s not the state motivation; he didn’t arrest her or shoot her w/ a service revolver Ex. Off-duty office in bar and 2 people at bar get into fight; off-duty officer intervenes & in the course beats someone up or shoots them; is the officer acting under color? The main consideration is the objective manifestations (i.e. the officer saying he’s such or showing a badge); other than that, if acting pursuant to guidelines is relevant; the victim’s subjective impression is only somewhat relevant Gibson: officer recipient of brutality complaints; he reports for psychological evaluation; determined to have atypical impulse control disorder; he was rendered unfit for duty & on medical leave; they allow him to keep his service revolver but signed a form that he has no authority to act as a cop; while on leave gets into fight with neighbor and shoots him with the revolver; under color? The department left him w/ some manifestation of authority but there nothing objective about the revolver (anyone can get a gun) If he told the neighbor he’s a cop & can arrest him, it doesn’t matter & doesn’t make him act under color 7th Cir.: Wishful thinking can’t make it true; you can’t will yourself into acting under color (i.e. someone who’s purely delusional and thinks they’re a cop isn’t acting under color) The officer didn’t really have police authority BUT a # of factors here may take this outside the general rule he has an objective manifestation of authority w/ the revolver; maybe it really isn’t wishful thinking Ex. Scout master cases where the master goes to the grade school & gets a troop of kids; the scout master isn’t employed by the school & the parents sign a form that they realize this is a private boy scout troop; courts tend to say that the scout master isn’t acting under color; the school didn’t employee him but he still has access through the school; there’s still a tie, but not enough Horseplay Cases Townsend—prison inmate & supervising officer; they played around a lot; officer scared inmate & accidentally stabbed him; the officer offers to take him to the infirmary & then later the prisoner sues Was officer acting under color of law? He was acting totally for pure personal horseplay; BUT he’s using the subordinate relationship to his advantage; the only way he can get the knife in is b/c of his employment; the prisoner could argue that he’s going along with the horseplaying b/c he’s getting benefits—can make sandwiches The court held it wasn’t a viable 1983 suit DISSENT: they left out relevant facts: guard realized there would be an incident report & the guard didn’t want to be implicated; the prisoner said he didn’t want to lie and the guard then rewarded him for not going to the infirmary he used his job & knowledge of the system to manipulate him; he couldn’t get him the rewards w/out his power 21 Schall v. Vasquez: state employee pointing gun @ head; using the service revolver to threaten someone wasn’t horseplay Sexual Abuse: state employee arguing that sexual abuse is personally motivated Ex. condition on granting divorce on the female petitioner sleeping w/ him; the Court held this was a judge who was conditioning judicial relief on giving in to his wishes and was under color Almand: officer helping woman find her missing daughter if she gave him sexual favors; he then raped her; Chicago officer fired for personality disorder allowed to keep his gun; she sues him under 1983; the majority said there was no state action (“any other ruffian”) Off-duty case whether the person is still using state power in thus becoming a state actor There are times when a person uses their state job to find someone’s home address and then when that person turns down advances at work and follows them home after hours good argument that harassment is under color b/c the person is using the power from the job to harass the woman In Almand, breaks in & rapes the woman eventually BUT HE WAS OFF DUTY AT THE TIME Looking at the point he got entry perhaps a state actor because using his police training to break down the door Raping her, like an ordinary individual DISSENT: he gains access and breaks in immediately after the rebuff before she’s had a chance to lock up; it was tied to his prior access using state authority SUMMARY Exceptions to the idea that a person who is a state employee acting within his scope of employment is acting under color and someone who’s off-duty isn’t issues of personal motivation A Constitutional or Statutory Violation Generally: this is about the 2nd element of a § 1983 case, whether it can be a violation of federal statutory law & in what instances The statute says “and laws” we’re assuming that the first under color prong has been satisfied; the statute has been interpreted to read “or laws” Maine v. Thiboutot (1980): welfare benefits under SSA denial from joint state & federal program; the state didn’t pay the benefits in accordance w/ the guidelines so the Ps argued they were denied money they were entitled to under the federal program; issue was whether § 1983 encompasses claims based on purely statutory violations of federal law & whether attorney’s fees could be awarded to the prevailing party; the Court held yes to both Sidenote: they sued Maine 11th Am. problem; can’t sue the state by name in federal court; you can get around this because it was filed in state court; this can’t happen now; states aren’t persons under § 1983, so you can’t sue them by name in state OR federal court; it would have to be against the governor of Maine, etc. Action under color: no issue with action under color b/c it’s the administrator is acting under state law; don’t need state action b/c it’s a statutory claim What “and laws” means: The Majority says take the language literally. Plain language “and laws” clearly embraces a violation of the SSA Not just limited to civil rights laws or EP laws nothing in the statute that Congress intended the word to NOT have its plain meaning; origin of the term was from a statute that was divided; doesn’t show Congress intended a different meaning Here, the statute was sort of ambiguous, so the court looked @ legislative history History of § 1983: No indication that civil rights was the only purpose of § 1983 When Congress originally enacted § 1983, it had a remedial provision & a jurisdictional provision; Congress split the statute up b/w these § 1979 = remedial provision (became § 1983) Jurisdictional provision District court: “any law” Circuit court: “laws providing for equal rights” ***Congress combined jurisdiction & codified the grant of district court jurisdiction using the circuit court law § 1343(3) [§ 1331 had AIC, so it wasn’t helpful] Majority: Congress didn’t change the language Dissent: difference in language is pure accident—it makes no sense to construe 1983 to grant substantive rights for which there’s no federal jurisdiction If § 1983 available, § 1988 makes attorney’s fees available 22 This worries the dissent—feared this is going to lead to a lot of litigated cases against states (b/c there’s no claim against the federal government (Bivens not available b/c it’s a statutory claim, not constitutional) & can’t get attorney’s fees from federal government even if they could sue it Dissent: Plain language not unambiguous; looking @ legislative history indicates that Congress meant “and laws” to include only EP & CR violations; this opens the door to “hundreds of cooperative regulatory social welfare enactments” that Congress didn’t intend to embrace; feared that people would go after local governments to get attorney’s fees; § 1983 could be appended to anything; “the decision confers upon the courts unprecedented authority to oversee state actions that have little or nothing to do w/ individual rights defined & enforced by the civil rights legislation of the Reconstruction Era” Limiting § 1983 for Statutory Violations [2 cases decided the year after Maine v. Thiboutot] Pennhurst: facts, challenge to state run hospital for mentally retarded; violation of BOR of Act (thus the state was violating the federal guidelines), SC held that BOR provision did not create enforceable rights & obligations; it simply stated congressional preferences w/r/t treatment The court held the claim couldn’t go forward under Maine v. Thiboutot It was merely a preference, “this is how we think you should spend your money”; it isn’t actually a right § 1983 covers only a deprivation of RIGHTS secured by the Constitution & (or) laws; there has to be a deprivation of a right that you secure under the statute Sea Clammers: facts, compliance w/ federal pollution control & marine protection laws; citizen suits after 60 day notice & other enforcement mechanisms; Court said there are alternative specific statutory remedies (Congress intended to foreclose implied private actions & to supplant any remedy that otherwise would be available under § 1983) Here, the Court said the party couldn’t bring the suit for a different reason—the statute provided for specific alternative remedies (60 day notice of complaint & compliance w/ other procedural hurdles) Congress clearly intended to supplant the § 1983 CAX by imposing additional hurdles on the π The Pennhurst Exception: Deprivation of Rights The Court has spent more time on this than Sea Clammers; there are 2 major decisions that seem contradictory (Wright & Wilder) Court originally willing to find that the statute gave rights with the 3-prong test Now, the law is a mess and we’re not sure whether the court uses the 3-prong test Alternative remedial procedures are relevant to the Pennhurst inquiry but is it merging with Sea Clammers or doing something else? The fact that someone violates a federal law & incidentally hurts you doesn’t give you a federal claim; the law must give you a RIGHT & the action must have deprived you of that right Wright v. City of Roanoake (1987): found amendment to housing act requiring reasonable utilities be included in rent for public housing enforceable under § 1983; the Court held that the reasonable utility allotment was not too vague to create an enforceable right (“sufficiently specific & definite to qualify as an enforceable right under Pennhurst & § 1983 & not beyond the competence of the judiciary to enforce”) Wilder (1990): Medicaid reimbursement to medical providers for rates the state finds are reasonable & adequate the court held this enforceable under § 1983 3-part test: Whether the provision in question was intended to benefit the putative plaintiff Here, intent was to benefit hospitals (the plaintiffs) If so, the provision creates an enforceable right unless It reflects merely congressional preference for a certain kind of conduct rather than a binding obligation on the governmental unit or The court finds a binding obligation to pay the hospitals adequate rates, not just a preference of their rates The interest the plaintiff asserts is too vague or amorphous such that it is beyond the competence of the judiciary to enforce There are definite guidelines & costs that the institution will incur; a court can figure out whether the reimbursement is adequate This case is later & goes into analytical depth DISSENT: The only obligation is that the state have a plan the secretary approved; the secretary’s job was to determine whether the rates were accurate; the state just had to follow the procedure; this won out in Suter 23 Suter (1992): Claim for federal reimbursement for expenses state incurs in administering foster care & adoption services; the state had to submit a plan w/ reasonable efforts to prevent children from being removed from home or to return the child to the home; The Court held there was not an enforceable right of the children under this act under § 1983 The Court didn’t mention the 3-prong test but didn’t even say that it was calling Wilder into question (just pretending it doesn’t exist) The act wasn’t that different from the Wilder scheme—submit plan to secretary, plan saying it’s using reasonable efforts to keep children in their home; child say no reasonable efforts being use ***How to reconcile the cases they are speaking to the secretary, providing generalized guidance, the focus is more systemic; the secretary needs to provide methods to make sure that the state is trying to keep the child in the home; the secretary shouldn’t approve the plans; this is guidance to the secretary The term “reasonable efforts” was a generalized duty on the state, not enforced by private individuals, but the secretary The reasonable efforts language does not unambiguously confer an enforceable right on the beneficiaries It’s a generalized duty to not take kids out of their home; it’s up to the secretary to determine whether states are fulfilling that generalized duty If the SECRETARY doesn’t think the state is using reasonable efforts, it should STOP FUNDING the program but doesn’t give children a right to certain efforts made on his behalf The burden is on the respondents to demonstrate that Congress intended to make a private remedy available to enforce the reasonable efforts clause of the adoption Act (Cort v. Ash) Gold State Transit Corp. (1989): individual could sue under 1983 for abridgment of NLRA rights by state enforcement of a policy the NLRA preempted, stating that apart from the exceptional situations in Pennhurst and Sea Clammers 1983 remains a generally & presumptively available remedy for claimed violations of federal law Blessing v. Freestone (1997): SSA state required to adopt a plan for enforcement of child support; the state had to collect the child support to offset the benefits from the federal government; if it collects the child support, the family has to get $50; here, the claim wasn’t that they weren’t getting their $50 but that under this system the state had to have a plan that the secretary had to sign off on saying that the state has a program in substantial compliance with the plan; the Court held that it didn’t create a private right b/c it was a yardstick for the Secretary to measure the system-wide performance; the Court looked at the 3prong test as factors and said: In applying the 3 factors, the plaintiffs must ID the rights they claim were violated w/ specificity; one cannot look at a statute as an “undifferentiated whole” (1) Congress must have intended that the provision in question benefit the plaintiff (2) The right must not be so vague & amorphous that its enforcement would strain judicial competence (3) The statute must unambiguously impose a binding obligation on the states The Court left open whether the provision of each family being entitled to $50 created individual rights The substantial compliance was merely a yardstick for the secretary to measure system-wide performance (not an individual right) Use 3-part test; break statute down into analytic bits The Sea Clammers Exception Court hasn’t spent must time on this Only 2 cases that it has found the exception to apply—Sea Clammers and Robinson The burden is on the state to show that Congress did NOT intend § 1983 to apply The existence of generalized administrative remedies does not satisfy it; there must be a private remedy, pursuit of which would be inconsistent w/ bringing a § 1983 claim Smith v. Robinson (1984): carefully tailored judicial mechanism including local administrative review & a right to judicial review showed Congress’ intent to foreclose other remedies Wright: HUD’s generalized powers to audit & cut off federal funds was insufficient to foreclose reliance on 1983 to vindicate federal rights; HUD didn’t exercise auditing power frequently & statute didn’t require individuals bring problems to HUD’s attention Wilder: no provision for judicial or administrative enforcement; limited oversight of secretary was insufficient to demonstrate an intent to foreclose relief altogether in courts under 1983; also the availability of alternative 24 state remedies didn’t foreclose enforcement b/c providers could not use those remedies to challenge the way in which rates were determined Suter: the Court didn’t find an enforceable right, so it didn’t consider Sea Clammers Dissent: ∆ must point to existence of alternative means for enforcement & to demonstrate by express provision or other specific evidence from the statute itself that Congress intended to foreclose 1983 enforcement; they will not lightly conclude that Congress so intended (only two instances, Sea Clammers & Robinson) Blessing: administrative mechanisms to protect π's interests didn’t foreclose § 1983; oversight powers were not comprehensive enough to close the door on § 1983 liability... "Substantial Compliance" Directed to Secretary---> Systemic...Aggregate Gonzaga University v. Doe (U.S. 2002): Whether FERPA created personal rights enforceable under § 1983 for damages; π was a student at Gonzaga & argued that a teacher certification specialist violated his rights by telling state licensing board that he was accused of sexual misconduct b/c it was releasing an educational record w/out his consent; he argues the school violated his rights in violating FERPA; NO, it didn’t; the Court held that Congress didn’t do so in clear & unambiguous terms; the nondisclosure provisions contain no rightscreating language; they have an aggregate, not individual focus & are primarily directed to the Secretary of Education; THUS it doesn’t create rights enforceable under § 1983 Congress must clearly & unambiguously create the RIGHT The Court took into consideration alternate administrative procedures for individual complaints to determine that Congress intended the disputes to be resolved there How do we reconcile this with Sea Clammers? Congress wanted centralized enforcement, not regional inconsistency, so it required everyone to go to one board; it wants the agency to speak w/ one voice; they weren’t using Sea Clammers b/c the review board is mere evidence that this is geared towards the aggregate & not based on individual cases; they want ONE standard; the system is in place to help the Secretary do her job & isn’t going to cut a check to the individuals To seek redress, the π must assert the violation of a federal RIGHT, not a federal REMEDY rights is not as vague as benefits/interests π's don’t have to show an intent to create a private remedy just a right b/c 1983 confers the private remedy already ANALYSIS Private university, so how under color? Footnote 1: because joint participation with the state in their teacher certification process & acting in accordance w/ the dictate of a state agency in disclosing info they require you to disclose ***The Court didn’t consider this issue on appeal Whether FERPA gave an enforceable right? It can’t just be a violation of the law but a violation that takes away an individual’s right The Court is trying to figure out Congress’ intent re: statutory interpretation; Blessing requires looking @ specific statutory provision It’s spending legislation based upon compliance with certain administrative requirements; Congress is putting spending decisions in the hands of the Secretary of Education; the language in the statute is relevant because it’s talking to the Secretary The statute speaks in aggregate terms, not individual terms it tells the Secretary not to fund schools with policies & procedures that violate FERPA; it talks about substantial compliance; nothing is suggesting that there are sanctions for a single instance of failing to abide by the statute just that the Secretary is to cut off funds to the schools; it’s a broad, systemic focus on individual rights The Court looks @ implied right of action cases i.e. Title VI and IX cases where Congress has spoken in terms of individuals specifically (“no person in the United States shall be subject to discrimination”) Concurrence (Breyer, Souter): shouldn’t always have to be unambiguous from Congress but agreed w/ the result here b/c statute not talking about individual rights; also the standard is too vague for the court to apply Dissent (Stevens, Ginsburg): there is a lot of rights-creating language; looks at precedent & thinks the Court isn’t following it; the alternate administrative procedures are inadequate (only 2 cases where they were found to displace the right); shouldn’t turn to implied rights of action cases b/c it’s a more exacting standard on 25 the π; no separation of powers issues b/c Congress already created a right of action in § 1983; even though Court says it’s not requiring the π to show intent to create federal remedy, it is requiring that Problem w/ using implied right of action cases: Bivens, we talked about implying a remedy when Congress creates a statutory right & doing the same thing with the Constitution (i.e. Title IX says nothing about a victim of discrimination being able to sue but the Court has interpreted the statute to give this implied right of action) For implied right of action cases, the court looks to whether Congress intended to provide a remedy but here, we already have 1983 the dissent says the implied right of action cases muddle the 2 prongs (right and remedy) so that you can’t keep it straight ***They are afraid that the upshot of this will be to require more than just the existence of a right; some indication that Congress wants the right to be enforceable (watering down the availability of 1983) but the majority insists it’s not really doing that NOTES on Gonzaga What is the significance of Gonzaga? Johnson v. City of Detroit (6th Cir. 2006): LBPPPA statute giving funding to try to eliminate lead-based paint especially in public housing; it required educational programs and gave funds to help remove leadbased paint; the issue was whether a TENANT could sue for a violation of the Act; the court said no; focusing on the language it doesn’t state that every person has a right to live in housing without leadbased paint; its focus is on education and abatement; giving the Secretary $ to improve conditions Lead based paint prevention act didn’t confer individual rights; court held that Gonzaga altered the landscape of § 1983 claims; still using Blessing’s 3-prong test BUT looking @ first factor intent to create rights NOT just benefits; Tenants still have trickle-down benefits, but it was an aggregate focus and did NOT confer individual rights 3-prong test Just a fancy rehash of Blessing whereby the Court doesn’t need to get to the second 2 prongs of the test because it failed the first prong; bulking up the first prong ***LOWER COURTS still by and large use the 3-prong test but they treat Gonzaga as having injected steroids into the first prong Harris v. Olszewski (6th Cir. 2006): People receiving Medicaid benefits could receive specific benefits from the provider they chose; it say any recipient has the RIGHT to select a provider; the state agency was requiring all recipients to get supplies form 1 company; the people wanted a choice in their provider and thus sued claiming they had a right Statutory language: “any individual” for Medicaid language DID CREATE individual enforceable rights Non-spending cases: 9th Circuit noted that Gonzaga focused on it but then the 7th Circuit held that Gonzaga was not limited to spending cases Post-Gonzaga cases: a lot of courts have found statutes providing enforceable rights (see p. 104 for examples); all of these cases do essentially the same thing; use 3-prong test and say that Gonzaga merely beefed up the first prong of the test Vague & amorphous statutes: Torraco v. Port Authority of NY (2d Cir. 2010)—court held that statute created individual right but was too vague to enforce because it would require every officer to be familiar with the firearms law of all 50 states; Congress obviously didn’t intend that result Regulations & treaties: Save Our Valley (9th Cir. 2003)—regulations can’t create enforceable rights after Gonzaga but can effectuate statutory rights as in Wright; Mora—presumption that treaties do not create privately enforceable rights in the absence of express language to the contrary Criminal statutes: Frison v. Zebro (8th Cir. 2003): Officer posed as federal census worker and obtained incriminating information for his investigation; against federal statute to masquerade as a federal official; the woman sued under 1983 claiming she suffered from harm of the officer’s violation of the false personation statute; the court held the statute didn’t give her an individual right It is rare to imply any private right of action from a criminal statute because they’re there to protect the public as a whole and not to give specific rights to would-be victims Similar to not having standing to sue for lack of enforcement of a criminal statute Relevance of private right of action cases: may be entwined 26 Sea Clammers is alive and well: Rancho Palos Verdes v. Abrams (U.S. 2005): dealt with rights of telecommunications entities to be free from private zoning regulations; everyone assumed that a right was created here but the statute gave a private remedy that had various hoops to jump through judicial review must be sought within 30 days; case heard on expedited basis; very limited remedies Allowing § 1983 cases would distort this alternate remedy because suing under § 1983 would be a lot easier; not those hoops to jump through The fact that Secretary can cut off funds doesn’t meet Sea Clammers Ex. Title VII violation; can’t bring 1983 to enforce it because to bring Title VII you must go through the EEOC and you can’t avoid this using 1983; Congress clearly intended a different remedial system Harris: act’s requirement that states grant opportunities for hearings was NOT inconsistent with private enforcement A.W. (2007): inconsistent with judicial review in 90 days of hearing officer’s decision and obtaining relief Link with State Action: D in 1983 action must act under color of state law but must have violated a federal statute It is usually going to be a violation of federal-state programs (i.e. Medicaid) This is why Powell dissented in Thiboutot—thought it was directing liability only to ½ of the problem— the state; you can’t bring a 1983 claim against the federal person who is administering the statute unless you can show that the federal official is acting under color of state law; if there were a conspiracy between the federal official and the state officials to deprive the person or some joint participation agreement Mirror image case: federal official forcing state official to not enforce the statute it doesn’t work to get the federal official (Tarkanian); the federal official isn’t acting under state law by virtue of coercing the state officials; you could argue the state officials are acting under color of FEDERAL LAW and they’re out of the picture/not proper defendants in certain situations where everything the state’s doing is because of federal coercion that they are acting under color of federal law Constitutional Violations Generally Still on the 2nd prong of § 1983 It mirrors the statutory violation considerations There’s not necessarily a § 1983 action simply because someone violates the Constitution; there must be a deprivation of a constitutional right (i.e. some provisions of the Constitution only speak to the structure of the government, not individual rights) (Thiboutot issue) Congress can preclude certain constitutional claims from § 1983 because it’s a statute; this is a Sea Clammers issue as to whether Congress somehow determined that a certain constitutional claim is not actionable Whether the constitutional provision creates enforceable rights Generally Must look at the substantive constitutional law claim This question is infrequently encountered Cases Lynch v. Household Finance Corp. (U.S. 1972): seems to say that ANY deprivation of constitutional rights is redressable by § 1983 but then later courts have disagreed with this (limited it to those that create individual rights) Golden State: NRLA preempting state law; the Supreme Court said there was preemption but no § 1983 action based on the preemption because the Supremacy Clause doesn’t give individual rights; it’s purely structural; the NLRA did give individual rights (under the statute) so there was still a statutory 1983 claim Violations of the Supremacy Clause are not redressable by § 1983; this is clearly just geared towards priority of the laws A person can’t bring a claim stating that he suffered a violation of the Supremacy clause because he is subjected to or regulated under a different law Carter v. Greenhow (U.S. 1885): Violations of the Contracts Clause cannot be redressed by § 1983; it just nullifies state law and is thus purely structural Dennis v. Higgins (U.S. 1991): The Commerce Clause [dormant and regular] creates enforceable rights that can be redressed by § 1983; it’s both a restriction on state power and an entitlement to relief for 27 violations; it gives an individual right to engage in interstate commerce free from state discrimination and burdens Heller (U.S. 2008): Second Amendment creates individual rights Whether congressional action precludes bringing the claim under § 1983 Generally Congress can limit constitutional claims from § 1983’s reach since it’s a statute Cases Robinson: EHA is the statute; the court determined that Congress set up an integrated scheme for enforcing a right to public education without regard to disability that the careful scheme indicated a congressional intent to preclude a statutory § 1983 claim under the EHA and also to preclude an EP claim alleging discrimination in education on the basis of disability violated the Constitution ***Raises an issue with anti-discrimination laws that have constitutional counterparts Ex. Individual working for U of M and claims discrimination (on basis of race, religion, or gender) and that person could bring a Title VII claim, having to go through the EEOC but the individual could also claim it was an EP violation and bring a § 1983 constitutional law claim We know you can’t bring a § 1983 claim alleging a violation of Title VII Can you bring a § 1983 claim alleging violation of EP? Lower courts find nothing in Title VII that precludes bringing the § 1983 claim; the constitutional claim is sufficiently independent form the statutory claim and there’s no indication that Congress, in enacting Title VII, intended to preclude the constitutional claim Fitzgerald v. Barnstable School Comm. (U.S. 2009): Parents suing school district for violation of a child’s rights from being sexually bullied under Title IX and § 1983; two-part test for alternative remedial intent of Congress (Sea Clammers issue); the Supreme Court relied on Sea Clammers and Robinson and concluded that Title IX did NOT preclude the constitutional claim There is the congressional intent consideration as in statutory cases BUT with the constitutional claim there’s an added dimension of the contours of the claims: Two-part test: (1) no comprehensive remedial scheme and (2) contours of constitutional and statutory claims diverged (1) no—it was an implied cause of action case (2) Title IX was broader & narrower and there were parts were it didn’t overlap with EP THUS, no indication that Congress intended to preclude all constitutional claims by enacting the statute Levin v. Madigan: SCOTUS granted cert for the question of ADEA; the 7th Circuit disagreed that ADEA precluded bringing an EP claim; it concluded there was no indication that Congress intended in enacting ADEA to preclude constitutional claims; ADEA had a comprehensive scheme but there was no indication that Congress intended ADEA to preclude people from bringing a constitutional claim if they could What constitutional provision applies and whether the P stated a claim Generally In most cases, it’s clear there’s a constitutional right at stake and there’s no statute; the average constitutional violation case raises different issues: The problem really comes to determine the constitutional violation and looking at that substantive area of the law Paul v. Davis states that not all torts violate the Constitution The courts have developed objective tests to determine at what point it becomes a constitutional violation Classic case = police brutality Person claiming, “my constitutional rights were violated”; but what constitutional right is violated? We know there’s a tort here (battery) but if just bringing a battery claim, you’re forced to go to state court (among other things, no attorney’s fees); just looking at the language of the Amendments, there’s nothing that speaks directly to police brutality; it’s a stretch (8A only governs when in custody); it’s clearly wrongful but it’s difficult to see what in the Constitution actually speaks to that; we know now these cases come under the 4A. BUT, we would more likely think it was a due process claim; deprivation of liberty w/o due process; there’s an interest in bodily integrity and that’s a liberty interest There’s support for this general idea in due process law 28 The problem with saying this is that it’s abusive conduct thus it’s a due process violation & thus § 1983 is a way to constitutionalize torts; we don’t want to constitutionalize all torts Paul v. Davis (U.S. 1976): Claim for defamation after cop distributed flyers w/ his face indicating he committed a crime; he brought not a tort claim but a Constitutional claim, claiming violation of DP liberty interest under 14A b/c this limited his freedom to shop; Ct held it didn’t violate his Constitutional rights thus 1983 was not available. The police did not actually deprive him of his liberty or property. Here, there was just a state actor committing a tort. Theoretical Issue: How do you determine when there’s a § 1983 constitutional claim as opposed to just a tort claim? Must point to a specific constitutional guarantee (Here, liberty wasn’t enough). Doesn’t matter that the deprivation was by an officer & thus was worse If the defamer weren’t a state actor, this would be nothing but a tort claim but since it is, P argues a DP claim exists If this is true, there are a couple of situations that would give rise to liability: Arresting someone if not right person Officer driving negligently & killing someone Reasoning: There is no interest in reputation alone under the Constitution; State law didn’t provide this interest & then take it away; and It wasn’t substantive DP under precedent Usually cases w/ stigma + altering the person’s status under state law w/ the defamation Worried about the slippery slope! If this is a 1983 claim, every tort becomes a 1983 claim (“14A becomes font of…”); it’s a vehicle for constitutionalizing torts; the P is claiming that the fact that the state has an interest that it protects under its tort law makes that interest an aspect of liberty You can’t use § 1983 to constitutionalize torts Brennan’s Dissent doesn’t see such a slippery slope if we limit it to the state of mind of the ∆; it must be INTENTIONAL to be an ABUSE of power (it still must be under color); the majority’s hypos are examples of mere negligence; saying that "1983 will be a font of tort law if intentional conduct is unconstitutional"; negligence can hurt someone but it’s not abusive (planting the seed of the state of mind objective test); you can’t negligently violate the Constitution Techniques for limiting § 1983 Paul—narrowing construction of the constitutional language O’Lone (1987)—no violation of 1A in prison b/c reasonable reliance on legitimate penalogical interests Sandin (1995)—limiting the scope of state-created liberty interests available to prisoners State of mind requirement/objective reasonableness test Baker v. McCollan (U.S. 1979): facts—Linnie stopped at red light; cop found that he’s wanted on drug charges b/c his brother used his license when he was stopped; there’s a valid warrant out for Linnie’s arrest but it’s based on his brother’s giving the cops Linnie’s ID; Linnie is taken to jail & held there for a couple days; Linnie brings 1983 suit against jail officials The 5th Cir: P stated a claim for “§ 1983 false imprisonment” PROBLEM is that the ct didn’t do an evaluation to see if there was a violation of a constitutional provision; they have to point to what was violated in the Constitution [this is what Paul said don’t do!] SCOTUS looked @ a possible constitutional violation it’s not a 4A violation b/c there was a WARRANT! Dissent & Concurrence: Ct failed to consider DP! They don’t want Paul to imply that DP is not available; it just must be an actual violation of DP. Blackmun: maybe a substantive DP claim if it shocks the conscience Stevens: maybe a procedural DP claim b/c there’s a deprivation of liberty w/o adequate procedures in place Outline To have a § 1983 claim, it’s not enough to just have a tort You need an actual constitutional violation You must thus point to the provision in the Constitution that’s at play There’s a preference for finding a specific constitutional home 29 Intersection of SDP and substantive constitutional law claims Generally: Not all torts violate the Constitution but certain tortious action is unconstitutional Certain egregious action may be so shocking that it violates the substantive protections of DP; comes up re: police brutality; early cases used 14A substantive DP to address them w/ a "shock the conscience" standard BUT SCOTUS narrowed the standard later & now police brutality comes under 4A w/ unreasonable seizure of the body Substantive due process still survives when no other specific provision of the Constitution is available (Lewis; example: pretrial detainees don’t have 8A rights; corporal punishment on students) Claims can implicate more than 1 constitutional guarantee so the court must examine each constitutional provision in turn not just the dominant one (Soldal) History: must be a specific constitutional claim or a violation of SDP; origins go to the incorporate controversy w/ BOR to state via DP of the 14A. Rochin: pumping stomach; what provision of the Constitution does it violate? The court says SDP b/c it serves in protecting against conduct that "shocks the conscience." Establishes that abusive physical treatment can violate SDP & that after Monroe the sword should work whereby the victim doesn’t just have to use suppression but can get damages Lower courts then treated police brutality as SDP under Rochin so what is “shocks the conscience”? Johnson v. Glick (2d Cir.): SDP claim; standard FACTORS (Wouldn't apply today...) (1) The need for the application of force, (2) The relationship b/w the need and the amount of force used, (3) The extent of the injury inflicted, and (4) Whether force was applied in a GF effort to maintain & restore discipline or maliciously & sadistically for the very purpose of causing harm [***most important factor—the motivation] This comes up later in 8A law. NOTES: In 1970s most lower courts were using the 4-part test for police brutality & saying that DP is what protects us against excessive force; BUT the court took issue w/ it in the mid-late-1980s if the claim has a specific constitutional home, you MUST use that specific constitutional home (Graham: If you can bring a claim under the 4A, you MUST; same thing w/ 8A). Lewis if the claim doesn’t have a constitutional home, then you can still use SDP; w/ SDP, there’s no one test going away from the Glick test, & saying that the standard depends on the situation w/ each factor weighing differently depending on the facts Currently, most police brutality claims come under 4A in looking at these, 2 issues come up Was there a “seizure” If no seizure, then can still possibly use SDP (Lewis) Was the seizure reasonable The Fourth Amendment Generally We are still looking to see whether there’s a constitutional violation; we know that just any tort committed under the color of state law doesn’t necessarily form the basis for a 1983 claim. Identifying the specific constitutional provision at stake is the most important in 14th Amendment cases— courts do not allow “generic claims” for excessive force as a species of SDP (shocks the conscience + 4factor test); it was too fuzzy and open-ended TN v. Garner Facts: Cop shot & killed fleeing felon; there was no indication that he was armed or dangerous; CT held that shooting constituted a 4A violation—use of force, shooting, = seizure! It restrained his ability to move after the shot, thus it was a seizure; the Ct then looked to whether it was reasonable. Use of deadly force against someone who was not suspected to be armed/dangerous was NOT reasonable. Thus, 4A violation: (1) The force must be necessary to prevent escape or the suspect poses a significant risk of death or serious bodily injury to others (2) Balancing of nature & quality of intrusion on 4th Am. interests Note: Not looking at subjective state of mind of the cop. Objective Test. Seizure: Acquisition of control... 30 First big step for excessive force going to the 4th Am. home Note: nothing in this case said SDP was necessarily out of the question, so we need to know whether the court has a choice when it comes to excessive force Physical force, at least deadly force, can be a seizure [lower courts had a little difficulty extending this to non-deadly force b/c if it’s a beating, it also comes down to whether it’s reasonable. Lester (7th Cir. 1987): Balancing nature of the governmental intrusion; wouldn’t allow a jury to consider whether it shocked the conscience it wasn’t under SDP; the Supreme Ct later adopted this view—using 4A for police brutality applying a reasonableness test & NOT SDP. Could she say that this was an unreasonable seizure? Yes. 2 seminal cases: Brower re: seizure & Graham re: reasonableness; the idea that a claim that can come under the 4th Am. MUST come under the 4th Am. 3 issues What’s a seizure? If there is one, what’s reasonable? If no seizure, what role does SDP continue to play? Brower v. Cnty. of Inyo (U.S. 1989) [SEIZURE] Facts: police car chase where they set up an 18-wheeler as a roadblock around a bend to get π to run into it; it killed him; π sued under 1983 for unreasonable seizure under the 4A; the issue was whether the use of the roadblock was a seizure; Ct held that there were sufficient facts for this to be deemed a seizure COA: held that the roadblock wasn’t a seizure b/c the driver could’ve stopped & it was his choice in continuing that made the police not actually having seized him SCOTUS rejects—the same idea could’ve been used in Garner (if the dude didn’t run away, the cops wouldn’t have shot him) Rules Violation of the 4th Am. requires an intentional acquisition of physical control = the standard; it must be an intentional decision to control the person the fact that Brower was stopped by the very means that the police put in place to effectuate that stop Distinguishing b/w: police slipping on brakes & running someone over (unintentional acts) EVEN IF the person is actually a fleeing felon b/c the cops aren’t stopping him by means put in place to stop him The detention itself must be willful (even if they get the wrong person/thing); through means intentionally applied What if the cops said, we didn’t really want him to run into the roadblock? The question is not based on subjective intent, so this doesn’t matter; the question is an objective question of whether the person was harmed by the means put in place (objectively, if you put a barrier across the road, it will terminate someone’s freedom of movement) The roadblock was designed in a way to lead to the conclusion that it was unreasonable— the Ct has to evaluate the type of the roadblock It’s enough for a seizure that a person be stopped by the very instrumentality set in motion or put in place in order to achieve that result There must be proximate cause; the roadblock here was the proximate cause of the harm; you can’t say the decision to not stop was the proximate cause—there was a means put in place to effectuate a stop & the design was unreasonable For § 1983 liability under the 4th Am., there must be seizure that is unreasonable. Concurrence in judgment: intentional acquisition of physical control should not be the essential element; they can see situations where an unintentional act can violate the Fourth Amendment Graham v. Connor (U.S. 1989) [REASONABLENESS] Facts: investigative stop of diabetic who hadn’t done anything wrong; they beat him up and refused to give him sugar or look at his license to determine that he was diabetic; the Court held this claim is properly analyzed under the 4th Amendment’s “objective reasonableness” test, rather than under SDP The lower court analyzed it under SDP w/ 4-factor test, labeling it as a “1983 excessive force claim” & found there was no standing b/c the police didn’t act maliciously & sadistically— SCOTUS held this was error 31 There’s no such thing as a “1983 excessive force claim”; there MUST be a constitutional violation to have it come under 1983 Must use the 4th Am. here b/c it’s the most explicit textual source of the constitutional protection claimed here No one here is disputing that there was a seizure; the issue is whether the seizure was reasonable Rules The Ct should consider whether the application of a more specific constitutional right would govern; a single, generic standard doesn’t govern excessive force claims The analysis begins w/ identifying the specific constitutional right allegedly infringed by the challenged application of force The validity of the claim then must be judged by reference to the specific constitutional standard which governs that right, rather than to some generalized excessive force standard All claims that law enforcement officers have used excessive force—deadly or not—in the course of an arrest, investigatory stop, or other seizure of a free citizen should be analyzed under 4A & its reasonableness standard, rather than under a substantive DP approach You MUST use 4A when there’s a seizure in an arrest/investigatory stop; the Ct cannot choose whether to use 4th Am. or DP here it was the use of force to effectuate a stop Note: 8th Am. doesn’t apply until after an adjudication of guilt; SDP also doesn’t apply For reasonableness, 4A requires a careful balancing of the nature & quality of the intrusion on the individual’s 4A interests against the countervailing governmental interests at stake 2 key factors that are being balanced (we aren’t looking at the officer’s state of mind) Quality of intrusion—forced used, i.e. using a gun or putting someone in handcuffs Governmental justification—same idea from Garner Factors include, but are not limited to: The severity of the crime at issue Whether the suspect poses an immediate threat to the safety of officers or others Whether the suspect is actively resisting arrest or attempting to evade arrest by flight Reasonableness is objective; looking @ circumstances from officer’s POV at the time of arrest & whether the officer’s actions were reasonable at the time of arrest in light of the facts & circumstances confronting him, w/o/r/t underlying intent or motivation The Court cautions against having a hindsight bias; we knew he was diabetic when we read the case, but we need to evaluate it in light of what the officers knew @ the time of the arrest SEIZURE California v. Hodari (U.S. 1991): officers coming up to group of kids; officers start to chase them after they run & one of the kids throws down a crack rock; Ct held there was NO seizure of the crack rock b/c no physical force was used; it doesn’t apply to a cop yelling “stop” when a suspect flees; show of authority is still an objective test, whether a reasonable person would’ve felt free to leave (Mendenhall); HERE, the kid didn’t stop so it wasn’t a seizure UNTIL the cops actually tackled him the kid tries to get the rock excluded from evidence b/c the police unreasonably seized him when they chased him The Court is wrestling w/ a show of authority that doesn’t actually stop anyone—the Ct held that there wasn’t a seizure until they actually tackled him Attempted seizures; temporary submission to authority Brooks v. Gaenzle: suspect runs away & the cops shoot him; the bullet hits him but he’s not actually stopped; he keeps running away; 3 days later, the cops get him; HE argues that the cops seized him when they shot him—there was some physical contact & it was intended to stop him (it’s physical contact w/ means intentionally applied)—Hodari even says it’s a seizure when there’s physical contact even if it is ultimately unsuccessful! Here, we have a use of force that’s intended to bring someone under control & it’s ultimately unsuccessful, but it’s a use of force not a show of authority The 10th Cir: even w/ use of force, there needs to be termination of freedom of movement; it may be ultimately unsuccessful b/c someone who’s temporarily stopped might get away BUT they have to be stopped in the 1st place; the court said he wasn’t stopped here b/c he still had a 32 “spring in his step” the fact that he kept fleeing & cops never got physical control of him meant there wasn’t a seizure th 6 Cir. case re: temporary seizure: cops stop guy for a minute & say we want to talk to you; there was no use of force; Ct said it wasn’t enough b/c he didn’t submit to the show of authority; it was a decisionmaking process & here there wasn’t enough to show that he submitted Attempted v. Actual Seizure that Stops Working: Hodari, was a pure attempt & it wasn’t a seizure (the court held there needs to be some acquisition of physical control); even of the person eventually gets away, there has to be some initial acquisition of control Objective intent: officer intending to do something lesser and kills someone Keller v. Frink: ∆ is game warden who receives a report that someone killed a deer out of season; he gets his gun & finds the truck loading up the deer; he says stop & then fires at the truck & ends up shooting a passenger in the truck; they sue & D says it wasn’t a seizure b/c he was trying to mark the van for ID. The question isn’t subjectively what the officer really thought he was doing; it’s an objective question of whether when someone fires a shotgun at a moving vehicle, is it an intent to stop that person objectively Ct says the jury wouldn’t decide whether to believe the officer but when looking at the situation, when someone fires a gun at a moving vehicle, is it objectively an intent to stop that vehicle this is for whether it’s a seizure NOT whether it’s reasonable Vaughan v. Cox: police chase a truck they think is stolen; the passenger matches the description of the suspect; the cops fire into the truck & said it was to stop the truck or the driver; the cops were trying to stop the suspect not by shooting him but by stopping the car; they actually shot him, though; the issue was whether there was a seizure—the gun effectuated the stop but not in the way that the cops wanted it to Brower: the very instrumentality set in motion or put in place in order to achieve that result; ct said when we’re looking at objective intent we’re not going to be hyper-technical—not looking at whether everything went the way the cops planned “We cannot draw too fine a line” Points: (1) when you shoot at a moving vehicle, you’re trying to stop the vehicle; (2); this is like being shot by a gun by which you were meant to be bludgeoned—the cop pulled a gun intending to stop you with it Taser cases: cops saying I was reaching for my taser but accidentally grabbed the gun—the courts say it’s just like what the court was talking about in Brower—reaching for a weapon intending to stop the person with that weapon is enough! Other seizures: whether a person who crashes after a police chase can bring a 1983 action; other actions like setting fire to a home or threatening the use of force; getting the WRONG PERSON (Keller—trying to stop a car = trying to stop everyone in the car) Fire burning & bombing a home: whoever is in the house is seized; the police are exercising control over the house & whoever is in it when they use the means to take control are still subject to a willful taking Police dogs: dog isn’t a proper ∆; there’s no Respondeat superior for 1983; can you sue the officer, though? Ex. police think a burglar is in the building; police command dog to find him; the dog finds someone & bites him; the dog acquires control over him but not the person the cops are looking for; did the cops seize the person that was bitten? YES Brower: seizure occurs even when the unintended person is the object of the taking but the taking itself must be willful; it was an intent to control whoever the dog comes into contact; this is a case where the unintended person is the object of a WILLFUL TAKING Brendlin v. California: passengers are SEIZED when a car is pulled over REASONABLENESS Scott v. Harris: considering: risk of bodily harm that the cop’s actions posed to the respondent in light of the threat to the public that the cop was trying to eliminate; very helpful if the cop captures the chase on videotape This case makes it clear that Graham doesn’t establish a bright-line rule for reasonableness; in high-speed chase cases in which the officers eventually seize the car, there’s a high risk of danger to 1 person & an attenuated risk to a lot of other people 33 Note: just the chase isn’t a seizure; the person has to actually be stopped Abney v. Coe (4th Cir. 2007): motorcycle chase; it crashed & the cop ran over the driver; ct held that seizure was reasonable—whether the risk the officers posed to the suspect was greater than the threat to the public the officers aimed to eliminate; it is reasonable to risk harming a person who threatens others to prevent the threatened harm from materializing Other issues in reasonableness: Courts are divided over how to individually look at a specific use of force; whether one should look at each use of force separately or at the event as a whole; whether it should be a sequence or an ongoing set of actions; the courts are split on ALL of this Another issue is what types of evidence are relevant? Brown v. City of Hialeah: Racial slurs while beating someone up? The problem is that it’s supposed to be an objective inquiry; the fact that the officers have subjective malice doesn’t affect the question of reasonableness of the force; but one could argue that the evidence is still admissible for the jury to take into consideration—Graham FN 12: in assessing the credibility of the officer’s account of the circumstances! Victim of shooting having drugs secreting in mouth at the time of the shooting; the officer didn’t know; it may be relevant because it’s external evidence for the jury to use in assessing the credibility of the officer’s statements of how erratic the person was acting (i.e. taking PCP & acting psychotic) ^ evidence isn’t for the officer’s subjective state of mind Chew v. Gates (circuit): π resisted or was armed; # of arrestees & officers; nature of charges; & availability of other methods of control; utterance of racial slurs; violation of police policies? When something looks like the Fourth Amendment but really isn’t Problems Innocent person held hostage in a car subject to a police chase; the police shoot into the car & kill the innocent hostage (Medeiros); do the hostages have claims here? Have they been seized? The officers are deliberately trying to void hitting the hostage BUT this is like the deer case—they were trying to stop the car + Brower suggesting this is a seizure b/c it’s a case of using force to stop something that doesn’t necessarily go the way the cops planned it to + unintended person language 2 ideas: (1) if you’re seizing a car, you’re seizing everyone in the car, not drawing too fine a line; (2) cops are deliberately trying to FREE the hostage, so it’s really an accident (different from the dog biting case) The lower courts ALL say that the hostages are NOT seized, using the rationale that this isn’t like Vaughan b/c the cops are deliberately trying to get the situation under control by letting someone off the hook The Brower unintended person language: when the cops deliberately someone, they seize that person even if it is the wrong person BUT in an ACCIDENT or bad-aim case, the victim of the accidental shooting/stop is not seized Tire deflation of the suspect’s car; the suspect then hits and kills a family driving on the same street Ct held the family wasn’t seized; the family dying was an accident The lower ct's draw a distinction b/w cases in which police end up hitting someone they’re sort of aiming at but things don’t happen the way they wanted it to and accident cases Substantive DP Claims—14th Am.: so does the hostage have any recourse? YES, 14A SDP claim The lower courts say you can use SDP in cases of what looks like it could be a seizure but it’s not a seizure; 4A doesn’t apply b/c there’s no seizure! Thus, Graham’s more-specific home rule doesn’t apply! [***ask Coach K if the ∆, the actual suspect, could ever use this when there isn’t a seizure] County of Sacramento v. Lewis (U.S. 1998): Whether an officer violates 14A SDP by causing death through deliberate or reckless indifference to life in a high-speed auto chase aimed at apprehending a suspected offender; NO—only a purpose to cause harm unrelated to the legitimate object of arrest will satisfy the element of arbitrary conduct shocking to the conscience, necessary for a DP violation; motorcycle chase; passenger killed; court held 4th doesn’t apply because no seizure standard is arbitrariness; high-speed chases with no intent to harm suspects physically or to worsen their legal plight do not give rise to liability under 4A, redressable by an action under 1983 With a chased car hitting an innocent person, there’s no seizure—the cops aren’t intentionally running the person over 34 Is there an SDP claim? The court says YES in Lewis—could bring a 14A claim b/c no seizure, thus no more specific constitutional home The issue w/ SDP is that it’s a subjective inquiry! It must shock the conscience; we don’t know the standard/culpable state of mind that must be applied to the officer subject to a SDP claim there’s NO single SDP standard; it depends on the circumstances The standard in any given case depends on the constraints the officers are facing, i.e. with minimal need to make split-second decisions use deliberate indifference; with high-speed chases, there must be an “intent to harm” ***It’s clear that negligence isn’t going to be enough! It’s never actionable under SDP Ct said that in some circumstances, it’s deliberate indifference to satisfy the standard of wantonness—w/ medical care cases, for example these are cases where the officers aren’t faced w/ making split-second decisions; it’s more of a static situation BUT when the police are required to make split-second decisions, a higher standard applies— basically an INTENT TO HURT standard: “only a purpose to cause harm” this applies here to high-speed chases b/c the cop is trying to make a split-second decision Duration of seizure Graham see FN 10 [post-arrest cases, “beyond the point at which arrest ends & pretrial detention begins”]: left open whether 4th applies to excessive force b/w arrest ending & pretrial detention beginning; 6th Circ. applied it to booking; whether a seizure is a simple event or a continuing state; Supreme Court malicious prosecution could be governed by 4A and continuing through the trial; what if there’s a second seizure? This is a very important factor because it determines whether to use an objective or subjective standard (if 4th objective; if 14th subjective, but we don’t know the standard) Timing Arrest/Investigatory Stop: MUST use 4A. ***in b/w the 2: detention period; the court has long held that pretrial detainees are protected under SDP of the 14th Am. [but there are still people within the state’s control & deserve some constitutional protection; usually comes from the 14th Amendment] Goes back to Bell v. Wolfish—SDP protects pretrial detainees BUT the court has never decided when a person switches from the 4th to the 14th Am. & the circuits are in total disarray about this; 2 competing ideas Ex. someone has been arrested w/o using excessive force; taking him to the station & as they’re taking him out of the cop car at the station to go to booking, he says something & the cops beat him up—is this a 4th or 14th Amendment claim? (1) Seizure as a continuing state (still being handcuffed; how long does it continue, though?) Common sense tells us that seizure occurs while someone is under control J. Ginsburg in Allbright v. Oliver in dicta said, seizure continues as long as someone is under police control Most circuits agree that seizure is a continuing act BUT disagree on until when K thinks the 7th & 9th Circuits have the soundest view—the seizure continues until there’s some judicial hearing (PC hearing or arraignment or some other formal proceeding that determines whether the state has a right to hold the person); other circuits say it’s a considerable amount of time (2) Seizure as a single act (once under control, it’s post-seizure, thus DP applies) 4th Cir adheres to this; Riley—relying on a SCOTUS chattel case stating that seizure is a single act & not a continuous fact (Thompson v. Whitman) Post-Conviction: MUST use 8th Amendment Other seizures—involuntary hospitalization; rape; fondling; gun-point headlock Seizures of property: the 4th Am also applies to seizures of property; if the police seizure your property & it’s unreasonable, you can bring a § 1983 claim Soldal: Ct held that towing of mobile home was a seizure under the 4A; it could apply to repossessions, formally under PDP Also applied to pets as “effects” under the 4th Amendment 35 The key point is that since it’s a seizure of property, it’s the 4th Am.; if it weren’t the 4th Am., it would fall under procedural due process of law (Parrot); the issue is whether the person can dodge PDP/SDP & Parrot Real property: can come under the 4th Amendment Presley v. City of Charlottesville (4th Cir. 2006): state may map for hiking trail that included private property; the private property had “no trespass” signs on it and the city prosecuted her for it; the court held that the city violated her 4A right governs temporary or partial seizures; here there was meaningful interference with her possessory interests; 5th Am. takings was also available; presence of 4th mandated a dismissal of SDP though Pets as property The Eighth Amendment Conditions Objective Single, identifiable human need Use of Forceb > de minimus force Subjective Deliberate indifference (Farmer & subjective look) Malicious & sadistic Generally Comes up in prisoner cases a lot; they are subject to a lot of coercive action; not every use of force against a prisoner violates the 8A; at some point, though, the force amounts to Cruel & Unusual Punishment & does amount to an 8A violation; the ***key is how to draw the line This is another clear constitutional home for 1983 cases; there are similar issue w/ drawing a line b/w tort & constitutional violation Two components to an Eighth Amendment claim— (1) Deprivation was sufficiently serious (objective) The fact that you don’t like your jail cell doesn’t state an 8th Amendment claim (2) Officials acting with a sufficiently culpable state of mind (subjective) Types of cases are important, too Conditions of confinement cases (Wilson) Use of force cases (Hudson) Estelle v. Gamble [underlying these cases; first HUGE step] Facts: insufficient medical treatment case The court extended the 8A beyond the sanction imposed by the legislature/sentencing judge 8A can be applied to some deprivations that aren’t specifically part of the sentence but were suffered during imprisonment; must show a culpable state of mind (here, deliberate indifference) Ex. historically, it would be challenges to the punishment given, like the death penalty NOT how the punishment given is being carried out; here, the claim is about how the punishment is being carried out; it’s focused on an individual act/omission; something that happened or didn’t happen to you ***Individuals can sue on individual acts/omissions, not just part of the actual sentence; it applies to what happens to people in prison Thus, the 8th Amendment applies to individual actions that befall someone in custody! This is the FIRST modern 8th Amendment case under § 1983 The court held this was inconsistent with evolving standards of decency, thus it was an unnecessary and wanton infliction of pain; BUT it has to be DELIBERATE indifference, so state of mind is important Wanton and unnecessary infliction of pain is inconsistent with standards of decency, so it violates the 8th Amendment When is it just something bad and when is it W&U infliction of pain? The court says the mere fact of lacking medical treatment isn’t necessarily a W&U infliction of pain What makes something W&U infliction of pain is the deliberate indifference (knowing there’s a problem and doing nothing about it) For medical care, subjective prong = deliberate indifference and objective prong = serious medical needs (i.e. can’t bring an 8A claim b/c someone isn’t giving you aspirin) 36 Whitley v. Albers: Deliberate indifference doesn’t apply to all claims; shooting while officers trying to calm a riot; there was a lot more going on here To the extent there were competing considerations, the court will want more than deliberate indifference to give rise to an 8th Amendment claim The court turns to Glick and weighed competing interests— Whether force was applied in a GF effort to maintain or restore discipline or maliciously and sadistically for the very purpose of causing harm Looking at the relationship between need and amount of force & extent of injury inflicted Wilson v. Seiter (1991) Facts: conditions of confinement as cruel and unusual punishment—it included both trivial and non-trivial claims; the Ds claimed that some conditions didn’t exist or weren’t that bad and also said they were working on fixing some of the problems Rhodes v. Chapman: double-celling; not unnecessary and wanton infliction of pain (focused on the objective component); the Court said this case didn’t eliminate the subjective component … The Court held it can state an 8th Amendment claim; BUT the P must show the state of mind of deliberate indifference; RULES 8th Amendment requires BOTH an objective and subjective inquiry State of mind [subjective] The Court held there must be a state of mind inquiry because the concept of punishment necessarily involves something that has an element of deliberateness to it; you can’t punish by accident (like accidentally stepping on the toe of a prisoner) If pain inflicted is not formally meted out, some intent element must be attributed to the officer In this case, the state of mind is DELIBERATE INDIFFERENCE Estelle standard because medical care cases are in a sense conditions cases (whether you have decent access to medical care generally is a question of conditions) and there aren’t constraints facing the officers like in prison riot cases (don’t have to make split-second decisions) There must be an inquiry into a prison official’s state of mind when it is claimed that the official has inflicted cruel and unusual punishment Intent can be shown by the LONG duration of cruel prison conditions The conduct must be wanton, the definition depends on the KIND OF CONDUCT: prison disturbance, competing interests (very high state of mind); medical needs, deliberate indifference If there is deliberate indifference, the conditions have to be bad enough to meet the subjective standard Regarding conditions, a court can’t dismiss any challenged condition so long as other conditions remain in dispute for each condition must be considered for the overall effect—but nothing as amorphous as overall conditions can rise to the level of cruel and unusual punishment when no specific deprivation of a single human need exists The P said you can never just dismiss certain conditions as not being bad enough (i.e. insufficient locker space) because the overall conditions could be bad (wanted the Court to look at the totality of the circumstances) the Court said that was the wrong approach— there needs to be a specific, identifiable deprivation of a single human need, not just an amorphous overall conditions claim Examples of human needs: warmth, food, shelter, exercise It doesn’t mean that conditions can’t be looked at jointly (i.e. low temperatures and lack of blankets) PROBLEMS with requiring a culpable state of mind Can claim the conditions were the result of lack of funding, not an intent CONCURRENCE IN JUDGMENT Thinks conditions are PART of the punishment and thus need not a state of mind inquiry but only an objective inquiry Estelle and Whitley didn’t involve challenges to conditions of confinement (it was MORE SPECIFIC instances); intent shouldn’t be relevant here because prolonged conditions don’t really point to an 37 intent to deprive someone of something; “having chosen imprisonment as a form of punishment, a state must ensure that the conditions in its prisons comport with the ‘contemporary standard of decency’” 3 big problems with the majority Thinks conditions are part of the punishment If it is part of the punishment, there doesn’t need to be a state of mind inquiry; they aren’t episodic acts; conditions claims should be different from this 2-prong analysis and courts should just look at the severity of the conditions (objective); he would broaden the concept to what is meted out by the sentencing judge State of mind in conditions cases is unworkable Conditions are hard to link to intent; can’t talk about the subjective intent of an institution; conditions are institutional (it comes from different people over time); it’ll be hard if not impossible to determine who’s intent we’re looking at Insufficient funding defense Even if you can pin the blame on someone, that person will assert that insufficient funding caused it and thus there’s no intent to deprive; it was a deprivation that resulted from external circumstances; not having money negates deliberate indifference; they were trying to help but were stymied Hudson v. McMillian (1992) Prisoner beaten by officers; he was shackled and beat up by guards while the supervisor watched and told them not to have too much fun; The 5th Circuit dismissed the case on an objective standard held it wasn’t a “significant injury”; the harm suffered wasn’t serious enough, so: Issue—whether excessive use of physical force against a prisoner can constitute cruel and unusual punishment when the inmate doesn’t suffer serious injury; the Court held YES, it can RULES The legal standard = unnecessary and wanton infliction of pain what that means depends on the conduct that occurred Here, Whitley applies—whether force was applied in a good faith effort to maintain or restore discipline or maliciously and sadistically to inflict harm (basically Glick) Use of force cases—building directly on Whitley The extent of injury suffered is one factor; the absence of serious injury is relevant to the 8th Amendment inquiry but doesn’t end it Objective component: important for medical needs and conditions of confinement cases to determine whether it comports with society’s expectations; here, though, contemporary standards of decency are already violated with the use of excessive force—whether or not significant injury is evidence [exception: when there’s de minimus touching/force] The court rejects the argument that there needs to be a serious injury—no requirement because the objective requirement depends on the claim and looks to evolving standards of decency; any time someone maliciously and sadistically uses force, it’s objectively a bad thing But, use of force does need to be more than de minimus (a push won’t suffice, even if M&S) ***It’s a very low objective standard and a very high subjective standard The actions were against prison policy and thus BEYOND the scope of punishment ties in with Scalia and Thomas’ opinion; whether a random, unauthorized use of force is even punishment, the Court does not decide this issue See Scalia and Thomas Concurrence in part & judgment (Stevens): no disturbance; malicious and sadistic standard is misplaced Concurrence in judgment (Blackmun): doesn’t join Court’s extension of malicious and sadistic standard but thinks that there’s no need to show significant physical injury; focused on psychological harm; wants to prevent ingenious torture with harms that don’t leave marks Dissent (Thomas & Scalia): only significant harm should be actionable; doesn’t agree with eliminating the objective component; doesn’t think the subjective component should be as demanding as the court requires; excessive force may not even be as bad as prolonged terrible conditions If we’re looking at state of mind, just use deliberate indifference (guards shackling the dude in this case had nothing to do with a riot; there weren’t competing interests here) 38 There should be a serious injury requirement Footnote 2: these really aren’t 8th Amendment claims because they’re isolated, unauthorized uses of force; it isn’t punishment in any meaningful sense if this comes under the Constitution at all, it should come under 14th Amendment PDP (Parratt) Basically, it’s a state tort case and as long as there’s a tort remedy, it’s enough (this hasn’t caught on with a majority of the court) Notes & Questions Hope v. Pelzer (2002): shackling up a prisoner and not giving him water and taunting him; AL had a chain gang requirement—they had a system in place where the prisoner who didn’t do the assigned work on the gang or acted up would be returned to the prison and hitched to a post in the prison yard until he “agreed to go back to work”; the regulations said the prisoners must get water and bathroom breaks every 15 minutes (here, he was handcuffed for 7 hours without any breaks); he claimed this violates the 8th Amendment: unnecessary and wanton infliction of pain includes those punishments totally without penological justification; clear lack of an emergency situation; the Supreme Court had no problem finding it was an 8th Amendment violation This was an unnecessary infliction of pain; it wasn’t in response to a security threat; leaving him hitched in the sun is a gratuitous infliction of pain—there was no penological justification This was an immunity case, so the 8th Amendment was talked about only in passing in the court’s opinion Problem: distinguishing conditions from use of force cases Objective inquiry: this was bad enough; it was an unjustifiable use and infliction of physical pain regardless of whether you look at use of force or conditions Subjective inquiry: options It switches from M&S to DI Only M&S (all use of force) DI (part of conditions)—this is what the circuit court used; BUT it didn’t really have to decide because M&S was satisfied, too No state of mind needed (White: part of the punishment; intent is implicit; but the majority rejected White’s opinion so we can’t really use this) ***THE point: it’s difficult to characterize the cases as either conditions or use of force Also issues when the guard watches someone beat an inmate up—is the guard tolerating a condition or is this more use of force (most courts would say conditions + DI) Farmer v. Brennan (1994): Transsexual in male prison who was beaten and raped; for deliberate indifference, the court held the P needed to show the officers’ knowledge of the violence and history of inmate assaults; somewhat equating it to recklessness BUT the court rejected the objective, civil law standard: must be both aware of the facts and must draw the inference What does deliberate indifference mean? The Court held DI is the standard here, but what does the P have to show? Civil tort law: deliberate indifference is objective; disregarding substantial risk of which someone knew or should’ve known Criminal law: deliberate indifference is subjective; the Court quotes the MPC—conscious disregard of a substantial and unjustifiable risk; the person needs to know of the risk and then disregard it ***This is what the court uses; the subjective standard Problems: The defendants are just going to argue that they didn’t know of the risk; this feeds the ostrich mentality of deliberately not learning of the dangers The Court tries to cope with this: one can prove subjective deliberate indifference without actually reaching inside someone’s head because of the obviousness of the risk may mean the person actually knew of it; also the officials don’t have to know of the SPECIFIC risk to the specific individual Claim: putting someone who for all intents and purposes is a woman in the male general population will lead to very predictable results (namely, the rape and attack here) This is a faulty classification claim (putting the prisoner in the wrong group) 39 Serious medical needs: serious medical need is one that has been diagnosed by a physician as requiring treatment, or one that is so obvious that even a layperson would easily recognize the need for a doctor’s attention (whereby medical verification need not be had) Helling v. McKinney: dangerous levels of ETS exposure can form an 8th Amendment claim; here, the inmate was celled with someone who smoked 5 packs of cigarettes a day; it’s enough that the prison officials were deliberately indifferent to long-term exposure to ETS; risk must be one that society chooses not to tolerate and that prison officials’ current attitudes and conduct manifest deliberate indifference Note: there doesn’t need to be actual sickness yet; it’s enough if it’s an exposure to a risk that society doesn’t tolerate Example: asbestos—society doesn’t tolerate this Whether Ds were deliberately indifferent: looking at their current state of mind; it’s not enough that the officials let it continue but looking at the time frame of the challenge and whether their attitudes manifested deliberate indifference This all goes to White’s fear of lack of funding defense we’re looking at subjective indifference or current subjective indifference; would lack of funding work? Ex. TN Case: old prison with no AC; some prisoners suffered a heat stroke and some died; they brought a conditions claim, arguing the conditions were unconstitutional under the 8th Amendment; the officials argued they didn’t have money to install AC (no one is contesting that there’s a deprivation of an identifiable human need); the court will not let them just claim lack of funding BUT will look to see if they asked the legislature for money, could purchase fans, could move out especially vulnerable people There isn’t a stark distinction—you must try to ameliorate the situation short of a large expenditure of cash Baze v. Rees: the method of execution can violate the 8th Amendment if deliberately inflicted pain for the sake of inflicting pain; it didn’t present an objectively intolerable risk of harm Wilkins v. Gaddy: De minimus: Supreme Court held this didn’t mean that the prisoner had to show more than de minimus injury Prison Litigation Reform Act: prisoners must exhaust administrative remedies before suing It has reduced the # of prisoner lawsuits but some say it’s gone too far; the Act was enacted in 1995 and it put a lot of procedural burdens in place; it is not usually the case in 1983 that the P has to exhaust administrative remedies; also the prisoners have to pay out of their inmate accounts (can’t proceed in forma pauperis); there is also a 3-strike rule (with 3 frivolous suits, court can dismiss subsequent frivolous suits) 42 U.S.C. § 1997e(e): prisoner can’t bring a federal civil action for mental or emotional injury without a prior showing of physical injury McKinney: ETS claim; they can’t prove prior physical injury; the courts are unclear on these cases What is physical injury? 6th Circuit—non-de minimus harm being left to languish in unsanitary cell is physical injury, not necessarily physical injury but a really bad condition Hudson said you need more than de minimus use of force but NOT more than de minimus harm (there’s a difference—the former is incredibly minor force, like a shove, but it doesn’t require that there be any measurable harm) Wilkins said that this is inconsistent with Hudson—it’s an 8th Amendment case, though, not falling under the PLRA Some courts have limited the reach of the physical injury provision but none have held it unconstitutional If you don’t have a physical injury, what happens? Lower courts say this requirement serves to prevent compensatory damages not as prohibiting injunctive or declaratory relief or as preventing nominal or punitive damages Why are nominal damages good? You can still get attorney’s fees because you’re a prevailing party Some courts say that the physical injury requirement doesn’t apply to the 1st Amendment (religion claims—denial of prayer or making the inmate eat foods prohibited by their religion) and to Equal Protection claims, but they can get damages; they aren’t suing for an emotional injury so § 1997e doesn’t apply! 40 Justice Thomas’s dissent: questions regarding the significance of a state tort remedy in determining whether a prisoner can establish an 8th Amendment violation; it will come up with the Parratt discussion; it’s also relevant for unprovoked assault cases (Pelfrey v. Chambers—cutting someone’s hair) Prisoner SDP Claims: Whitley—plaintiffs claimed a violation of their 14th Amendment SDP rights; they said the 8th Amendment was the PRIMARY source and must be used when it applies; DP doesn’t provide any greater protection than the 8th Amendment; does this narrow the 14th Amendment, as well? Scalia’s opinion in West: how does he view the relationship between the 8th and 14th Amendments [prison doctor acting under color of law]; doesn’t think the physician acted under color of state law—can’t inflict punishment within the meaning of the 8th Amendment; thinks it should fall under SDP of the 14th Amendment with deliberate indifference Limitation on Prisoners—Ingraham v. White (1977): 8th Amendment only protects convicted prisoners; it doesn’t apply to other forms of punishment (i.e. paddling school children); in a footnote the court did state that it was possible that some punishments not labeled criminal could be sufficiently analogous to criminal punishments to justify applying the 8th Amendment Intersection with Habeas Corpus: habeas—to obtain relief from custody; a write of a person that’s unconstitutionally confined to obtain release; it’s not easy to get a writ of habeas corpus; it requires exhaustion of state remedies (pursuit of all appeals throughout the state system before you can seek habeas); more recent statutes have narrowed the standard of review under habeas (lots of procedural restrictions); because of these restrictions, the P would prefer to use § 1983 Preiser v. Rodriguez: Challenges to the validity or duration of confinement must be brought under habeas corpus NOT § 1983 Cases at the core of habeas: Invalidating the conviction or Reducing the length of confinement (ex. challenges to good-time credits) ***Problem: claims that undermine the constitutionality of confinement but say they’re seeking relief that’s not available in habeas (i.e. getting damages for your unconstitutional conviction) the Supreme Court doesn’t allow this; any case that undermines the constitutional validity of confinement is challenging the fact/duration of the confinement Recently, the Supreme Court is more receptive to 1983 cases that could lead to the lessening of confinement the Court has said where 1 possible outcome is release or reduction of confinement, it doesn’t mean it has to come under 1983? Heck required the plaintiff to resort to state litigation and federal habeas before § 1983 is not implicated by a prisoner’s challenge that threatens no consequence for his conviction or the duration of his sentence Where the court refused to apply Heck: Court refused to apply it in charge of threatening behavior and subjected him to a mandatory prehearing lockup in retaliation for prior lawsuits Nelson v. Campbell: challenge that went to the conditions of the prisoner’s confinement could come under § 1983 Wilkinson v. Dodson—could challenge constitutionality of state parole procedures because it would not necessarily spell immediate or speedier release for the prisoners Here, the court said they could bring this under 1983 because their relief won’t necessarily get them out of jail faster—they’re just getting a new hearing Hill v. McDonough—three-drug lethal injection procedure challenged; court allowed it to come under § 1983 because it would not necessarily prevent the state from executing him D.A. v. Osborne--§ 1983 claim could go forward to compel release of biological evidence for postconviction DNA testing because the tests could support a finding of guilt Court said this could come under 1983 because it doesn’t necessarily mean the person will get out of jail; the DNA evidence could confirm the conviction Lack of turning over Brady material: this is always exculpatory so it would implicate the fact/duration of confinement Pretrial Detainees Generally: cannot bring suit under the 8th Amendment because no conviction yet; they can bring SDP claims, challenging either conditions of confinement or excessive force (Graham v. Connor recognized this) 41 However, these claims tend to mirror 8th Amendment claims BUT, since they’re under SDP, what standard applies? Here, the law is a total mess and is circuit-driven Conditions cases Bell v. Wolfish: whether conditions amounted to punishment; absent a showing that it was an intent to punish, the determination will turn on whether an alternative purpose to which the restriction may rationally be connected is assignable for it & whether it appears excessive in relation to the alternative purpose State has no right to punish detainees but does have a right to confine someone & there will be thus restrictions on their freedom; the test is geared towards this ***Specific 2-prong analysis: (1) whether disability is imposed for the purpose of punishment or whether it is but an incident of some other legitimate governmental purpose (i.e. not punishment would be a strip search after a visit from someone outside the cell; the strip search isn’t punitive but to safeguard inmate safety) [intent] (2) is that restriction rationally connected to the end or whether the restriction is unduly harsh in relation to that end (i.e. is the strip search unduly harsh to safeguarding inmate safety—here, the court said no given the likelihood that someone may pass contraband to an inmate during a visit) [proportion] Courts use this for restrictions cases Other cases re: pretrial detainees tracks 8th Amendment conditions claims exactly Estelle for medical care Farmer for excessive force lower courts are split on whether to use deliberate indifference or M&S Classification or detainee suicide, courts use DI Medical care, use Estelle and DI Restrictions, Bell ISSUE: when Bell applies and when DI from 8th Amendment context applies; but everyone agrees that these claims come under SDP and are either handled the same way as 8 th Amendment or somewhat different Involuntarily Committed Mental Patients: Generally: similar issues to detainee cases; ex. persons committed in mental institutions; they get protection under SDP but what standard applies? DP requires the state to provide them services that are necessary to ensure their reasonable safety from themselves and others DeShaney—right to Reasonably safe conditions of confinement, Freedom from unreasonable bodily restraints, and Minimally adequate training as the interests may reasonably require Youngberg—balancing plaintiff’s liberty interests against the relevant state interests; court must defer to professional judgment; only liability for the professional if there’s a substantial departure from accepted professional judgment, practice, or standards as to demonstrate that the person responsible actually did not base the decision on such a judgment Unique standard for mentally handicapped person involuntarily committed to a state hospital First, the court said that SDP guarantees a right to care & minimal restraint (a right to the least restriction possible) and requires the state to provide enough training or rehabilitation to enable someone to live w/ a minimum of restraint if the person can function with instruction outside the cell, the state must provide that instruction so that they can do that Using a professional judgment standard to determine what’s enough—if decision made by a professional it’s presumptively valid; there’s only liability if it’s a substantial departure; basically, if the professional is acting professionally, we defer to that decision Who is entitled to protection (not retarded patients; maybe involuntarily placed foster children) and when does the professional judgment standard apply? It applies to people involuntarily committed for psychiatric or developmental reasons Foster children—a number of courts use this professional judgment standard in challenges to foster care placement 42 Prison cases—some say it should be used in those cases; if taken to far, though, it undermines the 8th Amendment law What’s clear? We’re dealing with SDP and there’s some sort of right 8th Amendment Review Dual objective/subjective analysis When there’s an 8th Amendment case, it HAS to come under 8th Amendment SDP can be a fallback Substantive Due Process Open Field: can be a fallback for the 8th and 4th Amendment claims; pretrial detainees and innocent victims of police chases These materials deal w/ recurring situations of cases that don’t have constitutional homes We know 4th Amendment applies to arrest/stop of a free person We know 8th Amendment applies if you’re a convicted prisoner challenging what happens to you (conditions, medical treatment, etc.) Issues: (1) which of these claims are properly brought under the specific constitutional provision, not the DP clause; (2) which claims are really just tort claims that do no raise constitutional concerns (Paul v. Davis and Baker v. McCollan); and (3) what standard applies if you do have a SDP claim Malicious Prosecution Generally: cases in which someone challenges trumped up evidence; P usually suing cops who caused the arrest by a proceeding based on either false info or totally trumped up info; note: P can’t sue prosecutor b/c of immunity On one level these cases are mere torts BUT there’s a state actor involved, so can you constitutionalize it? The early days brought 1983 malicious prosecution claims can we do this? NO says Albright; it must go under a specific constitutional provision, i.e. 14th Amendment SDP Baker v. McCollan: people didn’t know whether and how a victim of malicious prosecution could show a constitutional violation under § 1983 C/L elements: (1) institution or continuation of criminal proceeding by D against P; (2) termination of proceeding in favor of accused; (3) absence of PC for the proceeding; and (4) malice or primary purpose other than that for which the process was designed Others: conduct under color w/ 4 C/L elements—constitutional violation shown Some require conduct that’s sufficiently egregious, without reference at all to the common-law elements Albright v. Oliver (1994): Oliver, detective, found John Albright, Jr. was dealing drugs (look-alike drug w/ baking soda); later met w/ him & felt bad that he was being prosecuted; he then changed the name on the warrant to a rando dude in Chicago; this dude was subjected to a cash bond, & couldn’t leave the state; he also couldn’t go to a job interview; he sued for a SDP violation for malicious prosecution BUT Plurality held that he didn’t state a claim b/c it should’ve come under the 4th Amendment (“pretrial deprivations of liberty”); 4th was the specific constitutional provision but it the Court didn’t decide whether it amounted to a 4th Amendment claim here Harkening back to Ginsburg w/ the idea that a seizure is continuing Kennedy & Thomas concur saying Parratt should govern—PDP Souter says it’s a 4th Amendment claim but there’s no seizure Either way, the claim cannot be SDP; & there’s a very strong suggestion that it would be the 4th Amendment Meaning of Albright: what a 4th Amendment malicious prosecution claim must show; the lower courts have held that the cases can be brought under the 4th Amendment; there’s a split on what standard to apply—some look at whether it’s just a 4th Amendment claim with factors or just a constitutional approach Hernandez-Cuevas (1st Cir. 2013): 4th Amendment = objectively unreasonable while c/l claim required subjective malice; 4th claim + factors Sykes (6th Cir. 2010): four elements—none including a subjective inquiry; expressly refusing to require malice; mere constitutional approach Seizure: Burg (2d Cir. 2010)—summons, pre-arraignment and non-felony does NOT constitute a seizure BUT not being able to the leave the state is (Murphy) 43 Where does the 4th leave off? Albright indicated that one element for c/l action for malicious prosecution was termination of the prior criminal proceeding in favor of the accused; Haddock—state conviction reversed on appeal didn’t bar § 1983 4th Amendment false arrest & malicious prosecution claim False Imprisonment Generally: lower courts say SDP; would it fit better under the 4th? one court said being held in jail for a year without exculpatory evidence violated 4th Amendment; these are cases in which someone isn’t really challenging HOW they were brought into custody but being kept in custody after it’s clear that the state has no right to continue to keep them Baker v. McCollan: we know you can’t bring a § 1983 false imprisonment case; there must be a constitutional claim Blackmun: you need a constitutional claim; it can be SDP if it shocks the conscience If procedure is bad, it could be PDP Here, most circuits will use SDP if the detention shocks the conscience Ex. being held for a long time despite repeated protests of mistaken identity or if someone is being kept a long time even though there’s an order to release them If something about the improper confinement that shows a total indifference to the right to confine, courts tend to use SDP Armstrong: someone kept for 57 days without a judicial appearance = claim McCannon: deliberate indifference to misidentification Should this be brought under the 4th Amendment because malicious prosecution is? Some courts say YES—2d Cir. so long as someone is confined, they’re seized; if it’s unreasonable because there’s evidence that it’s the wrong person or there’s an order for the release, you can bring a 4th Amendment claim BUT, the majority position is still to use the SDP Confessions: SDP by coercive questioning? It’s not a 5th Amendment claim because the state didn’t incriminate the person! It’s statements that were coerced but not used; the courts recognized a possible SDP claim if it shocks the conscience SC recognized the possibility of such claim even when the incriminating statement isn’t used; it must still shock the conscience and this is a high threshold; lower courts haven’t really found SDP claims that were successful; it’s a really high standard Chavez—failure to give Miranda does not itself give rise to a claim under § 1983 Tinker—police told girl that her attorney wasn’t really representing her, that bad things will happen if she gets another attorney, and that she’ll fry in the electric chair—the court said this wasn’t bad enough to violate SDP (perhaps physical torture would work) Exculpatory Evidence: 6th Cir. held that a person could bring a § 1983 claim for failure to provide the prosecution with exculpatory evidence under Brady; it was a PDP claim! Abuse of Civil Process: misapplication or bringing proceeding under an invalid statute under § 1983? Andree, 7th Cir. 1987: NO for unconstitutional ordinance because it wasn’t plainly unconstitutional Richardson v. South Euclid, 6th Cir. 1990: prosecuted under unconstitutionally vague ordinance; the court held that the defendants were given all due process they had a right to Land Use: Denial of zoning requests come up because the people on the zoning board want the land for themselves; permit denials and related land use decisions can violate SDP; the question is whether it shocks the conscience; 6th Cir., Pearson, SDP right to not be subjected to arbitrary or irrational zoning decisions Land zoning: it’s definitely a misuse of process but does it violate anything? The lower courts say these cases do sound in SDP, where the decision is purely irrational and shocking Lead cases in the 3rd Circuit: arbitrary denial of zoning application due to a board member’s personal interest; wholly/purely irrational (tough standard to meet) Protected Personal Interests Interference with Bodily Integrity: fundamental interest in liberty under SDP SDP: regarding personal integrity; this ties in with traditional SDP claims; it’s well-established interests in liberty Liberty interest in freedom from physical and sexual abuse (i.e. judge asking for sexual favors; police raping someone) Rape by police: 4th Amendment, some say it’s not really a seizure because the point isn’t to arrest the person Liberty interest in privacy 44 Liberty interest in freedom from bodily restraint and punishment Corporal punishment in school—Ingraham, U.S. 1977, no required hearing before punishment inflicted BUT lower courts have held that severe corporal punishment can violate SDP (majority position); some say it can be analyzed under the 4th; you can’t bring an 8th Amendment claim because not convicted of a crime High school sports coaches included; 5th Cir.—no claim stated as long as state law provides a remedy Psychological abuse: just a tort or actionable under 1983? Abeyta—it can’t be used for calling a student a prostitute Abuse of a mentally handicapped person, didn’t state SDP because it didn’t shock the conscience Employment Decisions: arbitrary employment decisions denying SDP; easy when P has a property interest in the job (i.e. tenure); some circuits require more—that the decision was arbitrary & irrational Academic Decisions: Regents v. Ewing (U.S. 1985)—arbitrary educational decisions can violate SDP but court’s must refer to educator’s expertise Equal Protection as a substitute for SDP Generally: “Equal Protection is the new SDP?” that’s what we’re trying to figure out; it’s desirable to use because the P doesn’t have to show that he/she was deprived of a property or liberty interest EP claims: The P is arguing that the state treated him/her unfairly and are going to make a constitutional case out of it—generally, you’d think it would go to SDP because there’s no constitutional home for it (can’t use 8th or 4th; can’t use PDP); they stray from EP because the person isn’t challenging a discriminatory treatment based on membership in a class (racial or religious); it’s that the government treated me unfairly because of something about ME not a class; but other branch of EP? Fundamental interest (court using strict scrutiny if the state is making classifications on who can exercise a fundamental right—comes up in right to vote and access to court cases); land use cases don’t bring up this fundamental right It SEEMED like EP was inapplicable until Olech Why EP is more attractive than SDP For EP, there doesn’t have to be a deprivation of anything Employment: people fired from their job for unreasonable reasons if there’s employment at will, you don’t state a claim; then you can claim you’re a class of one The courts have recently cut back on these claims—in 2008, the court in Engquist said that Olech doesn’t apply in the public employment context because it would undermine employment at will Village of Willowbrooke v. Olech (U.S. 2000): EP claim for arbitrary easement required of P to get access to water supply; class of 1 but needed to show that it was arbitrary and intentional discrimination; subjective ill will issue not reached This wasn’t based on a fundamental right or membership of a class ***IT opened up EP considerably, but the court later cut back on it The court didn’t require a showing of subjective ill-will but also didn’t rule out that it might be relevant! Breyer raises this in his concurrence calling for such an ill-will or malic requirement to bring class of 1 claims The circuits are in disagreement on this point Restrictions on Olech Engquist: Class of 1 theory doesn’t apply in public employment context, thus the employee must show class-based animus; does it apply to potential employees? (6th Cir. Bower); applied to government contractor’s claim and excessive regulatory scrutiny; distinguished when the decision is inherently subjective If it allowed the doctrine to apply in the public employment context, it would eliminate employment at will Also, the government is acting in a unique role in employment cases because the government always has more freedom to act in a subjective manner when it’s acting as an employer rather than as a regulator How far does Engquist reach? 45 Logically, it applies to employment decisions Douglas Asphalt (11th Cir.): government contractor; applied Engquist to that situation Kusel (2d. Cir.): key is whether the government is acting as a regulator (using its traditional, governmental coercive power) if yes, Olech applies Del Marcelle (7th Cir.): whether there is a clear standard against which to measure departures (if yes, Olech applies!); but this was a divided opinion Motivation in Applying Olech: Del Marcelle (7th Cir. 2012)—police not responding to assistance for harassment by motorcycle gang; the 7th Cir. believed the EP claim required a showing of animus; there was a split as to whether this was required How similarly situated must the person be? In class of 1 case, the similarity must be extremely high Whether claims are too insubstantial to raise a constitutional issue Rational basis review: Olech and rational basis relationship? One case, Christian Heritage, where court held there was a rational basis but it failed Olech PDP: Property PDP: Liberty PDP: Life SDP BOR Incorporation Negligence Parratt Daniels & Davidson Daniels Davidson Open question (1st Amendment type stuff) Reckless/Delib. Indiff. Hudson & Parratt Zinermon Zinermon Zinermon Zinermon Intentional Hudson Zinermon Zinermon Zinermon Monroe & Zinermon Black = constitutional non-category; it doesn’t exist Pink = reach of Parratt Green = Parratt doesn’t apply Procedural Due Process Generally “No state shall … deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” came from the law of the land clause in the Magna Carta (TN adopted the law of the land clause in its Constitution); most cases are about liberty and property and what’s at stake Analysis Traditional (1) Whether a constitutionally-protected liberty or property interest is at stake (property = legitimate claims of entitlement; liberty = 1st Amendment rights and some state-created interests); if so Liberty/property cases: usually involving a legitimate claim of entitlement to something (old property, holding title and new property, government benefits beyond a unilateral expectation) Property examples Teacher in Board of Regents expecting to be hired; this expectation was not enough to give him a property interest; it was a unilateral expectation If there were a contract in ^ giving the right to continued employment unless you commit a crime, then there’s a legitimate property interest Government sets out expectation of continued benefits absent some defeasing conditions (i.e. not filing documentation or doctor saying you’re cured) Liberty examples Fundamental rights that SDP protects (i.e. reproduction) Specific provisions of the BOR (i.e. free speech) Government giving claim of entitlement to liberty (i.e. if the government sets out the idea prisoners have an expectation for continuing on work release unless something happens) (2) What process is due 46 3-factor test (Matthews v. Eldrige)— (1) Private interest affected by official state action; (2) Risk of erroneous deprivation of such interest through the procedures used and probable value of additional or substitute procedural safeguards; and (3) The government’s interests—function involved and burdens with more procedures) Matthews: P was entitled to disability benefits; the government thought he was faking; P had a legitimate claim (property interest), so the court had to figure out what process was due Starting point: procedures in place Got a letter saying that the government proposed to terminate benefits; he had documentation of the reasoning of the government; he could respond in writing and submit documentation; the government made its decision thereafter He wants more An opportunity to be heard; an oral hearing so that he can walk in the room and show them Goldberg: welfare benefits; the court said that termination decisions are subjective; the P is usually poorly educated and cannot make his case in written testimony Risk of error with current procedures & value of additional/different procedures in light of the importance of receiving the benefits and the cost to the state The court held that the letter and written response was DUE process because the decision was not a credibility decision but a medical decision; doctors can express their medical opinions clearly and rarely did those disputes go to truthfulness Given the cost of the government giving full blown pre-termination hearings and continuing benefits during those hearings, the risk didn’t justify it Example: tenure contract (right to job unless you commit a crime); you’ve been either arrested and not convicted or it’s just a misdemeanor, so you think it’s not a “crime”; the government will say we can take away your right, you argue that your crime doesn’t fit the definition or you haven’t been convicted Example: right to continue working unless subordinate and there’s a dispute over whether you were honest to your employer, constituting insubordination ***BOTH: there’s a dispute and there needs to be some process to determine whether the government has the right to take away your property, so what process is due? [look at process in place] How important is the benefit KEY POINT: risk of erroneous deprivation through procedures used and probable value of additional or substitute procedural safeguards [how likely is it that the procedures in place are generating wrong decisions and how likely will additional procedures rectify this?] The government interest: looking at factors, such as efficiency; cost; and burden The traditional analysis was applied to cases with certain characteristics—deprivation was INTENTIONAL and the deprivation took place pursuant to an ESTABLISHED GOVERNMENT PROCEDURE 2 Exceptions Existed North American Cold Storage [emergencies]: here, the accusation was that poultry in their cold storage was putrid; if people purchased it, they would become sick; the issue was whether the owners of the cold storage were entitled to a hearing before the deprivation of the poultry; the Court said NO The Court held that in an emergency, the government can take action first and ask questions/provide process later This doesn’t mean that there’s no right to process; there could be post-deprivation hearings to provide compensation to the owner of the cold storage Key: post-deprivation process for compensation can be due process if an emergency prevents pre-deprivation process Ingraham v. Wright [hearing wouldn’t help]: Ps were paddled students who brought claims for beating without any pre-beating hearings; they brought an 8th Amendment claim (obviously, doesn’t help) and a SDP claim (courts use this now); and a PDP claim (which the court focused on) 47 The Court held that there was no point in having a pre-deprivation hearing because the risk of error is so slim and the cost is so great (hearing wouldn’t help) The child’s only interest was in not being disciplined in excess of the common-law privilege and the government had a strong interest in being able to run the school Little risk of error Value of additional procedures minimal THUS, no right to pre-deprivation process ***Note: this is a hotly disputed case; child brought claim in tort and received compensation; but can’t get unbeaten; but, post-deprivation process was all that was DUE What you get from the combination of these two cases is that there may be no need to predeprivation process and that tort remedies may suffice as post-deprivation process Using Matthews doesn’t guarantee pre-deprivation hearings All of these cases were intentional deprivations! There was also an established state procedure in place. The only question was if that procedure was sufficient to satisfy DP Parratt v. Taylor (1981) [loss is not intentional but purely negligent, not pursuant to some established process—what procedure is due?] Case: inmate ordered hobby materials to be shipped; he never gets it because he’s in segregation when it arrives; the person who’s supposed to sign and keep it doesn’t and it’s somehow lost—negligent act; brought a § 1983 claim to recover $23.50 (no minimum dollar amount in the statute), claiming that his PDP right violated when the officer negligently lost his property; he had a state tort remedy that he didn’t pursue; the Court held he didn’t state a PDP claim How it’s a federal case State action (guards in charge of delivering mail were acting under color of state law) Deprivation (loss of property even if negligently caused) State of mind (§ 1983 doesn’t have one itself); only requirement is what’s implicit in the word “deprivation” Materials = property BUT without due process of law? Holding: There’s no violation of PDP where the P alleges a random & unauthorized act causing deprivation of property when the state provides adequate post-deprivation process For negligent deprivation by a random & unauthorized act, due process only requires postdeprivation procedures that can compensate The P is not expected to exhaust state remedies in order to bring the § 1983 suit; the point is that there is NO § 1983 suit because of the state process in place [there’s no guarantee that he’s going to win, i.e. even if he’s missed the s/l in the state, that doesn’t give him a § 1983 claim] Rules He satisfied the 3 due process elements BUT the Court had to figure out whether he was deprived with his property without due process of law—whether the state tort remedies satisfy the requirements of PDP requiring an opportunity to be heard in a meaningful manner Pre-deprivation proceedings are not required here because the loss is not the result of an established state procedure, thus the state couldn’t predict when the loss would occur the state action here wasn’t complete; the existence of an adequate state remedy renders it NOT a due process violation (the mere deprivation was not a constitutional violation) The state remedies just have to be “adequate” (not exactly equivalent to § 1983) Analysis Start with procedures in place: no pre-deprivation process but state post-deprivation process for compensation; issue is whether this satisfies due process Most cases require pre-deprivation process, but they all dealt with action pursuant to an established state procedure (someone intentionally acting in accordance with that state procedure), and the court would look to THAT procedure and determine whether it’s adequate Not all cases require pre-deprivation process, though: the Court uses the justifications for having post-deprivation process only are applicable here because it’s a random and unauthorized act (difficult/impossible for the state to provide a hearing before the deprivation takes place), like Ingraham There still needs to be process, but it can be post-deprivation 48 Are the Nebraska procedures adequate? They can provide compensation; aren’t as good as § 1983, but are “adequate” Other Issues Issue that drives Parratt: extent to which there may be some provision of the Constitution that serves as a residual claim for someone who says the government has hurt them, but there’s no other place to go; it’s the ultimate “fallback” claim; whether PDP is the last resort Paul v. Davis: a lot in common with this case; question of whether PDP can be a lurking remedy that would be available when a person acting under color of law commits a tort (constitutionalizing a tort claim) Other Opinions Stewart (concurrence): even if state unconstitutionally deprived P of property, the state makes remedy possible in line with the 14th Amendment Blackmun (concurrence): limits case to property deprivation (not life or liberty); that there may be some cases where procedural protection by the state isn’t enough; post-deprivation procedures won’t cure intentional acts Powell (concurrence in result): negligent acts don’t violate PDP even if there are full procedural protections; “I would not hold such a negligent act, causing unintended loss of or injury to property, works a deprivation in the constitutional sense. Thus, no procedure for compensation is constitutionally required” Marshall (concurrence & dissent in part): thinks negligent acts are covered by PDP; should look to adequate state procedures; BUT doesn’t think state procedures were adequate here BIG ISSUE: can we cabin Parratt? If it applies all the way to intentional deprivations of incorporated rights, then Monroe is gone. Hudson v. Palmer (1984): officers did a shakedown of a prisoner’s cell and intentionally destroy noncontraband property Whether a prison inmate has a reasonable expectation of privacy in his cell (4th Amendment) and whether the deprivation of property by state officials acting intentionally violates DP (14th Amendment) even where there are state tort remedies available The Court held NO to both The Court did extend Parratt to intentional deprivations by state employees acting under color of law The D argues that this is random & unauthorized and not pursuant to an established state procedure The P argues that this is an INTENTIONAL act, so the officer can provide pre-deprivation process because he knows he is about to deprive the prisoner of process the Court says, “the state can no more anticipate and control in advance the random and unauthorized intentional conduct of its employees than it can anticipate similar negligent conduct” ***The Court distinguishes the State and state actors The problem is that the state acts through state actors but in cases of PDP, at least, the acts of the employee do not bind the state; the question is whether the State can provide predeprivation process and if not, whether it provides post-deprivation process (footnote 14, consistent with Ingraham) The State seems to = legislature and top agency officials, those making policy, and whether they’ve provided through the mechanisms of state government, some opportunity for compensation Rules 4th Amendment: no reasonable expectation of privacy in the prison cell 14th & Parratt: Unauthorized intentional deprivation of property by a state employee DOES not constitute a violation of the procedural requirements of the DP clause of the 14 th Amendment if a meaningful post-deprivation remedy for the loss is available For both intentional and negligent deprivations of property, the state’s action is not complete until and unless it provides or refuses to provide a suitable post-deprivation remedy LIBERTY CASES: everyone thought the following 2 cases would address whether Parratt applies to deprivations of liberty and whether state remedies were adequate; the Court did something different Daniels v. Williams (1986): bodily injury (liberty interest) from pillow left negligently on the stairwell; P alleged violation of liberty interest in PDP; the Court held no violation of PDP 49 The DP clause is not simply implicated by a negligent act of an official causing an unintended loss of or injury to life, liberty, or property the Court overrules Parratt to the extent that it states that a mere lack of due care by a state official may deprive an individual of life, liberty, or property under the 14th Amendment (policy—not a font of tort law) The term “deprivation” implies necessarily some deliberate act, either intentional or at a minimum indifference to whether the loss occurred ^^^ Powell’s reasoning in Parratt Thus, if there’s no deprivation, the state doesn’t have to provide process at all (the state doesn’t have to do a thing) For § 1983, there must be a violation of a constitutional right; in some instances (like this one), negligence won’t be enough Here, because the act was merely negligent (and negligence does NOT constitute a deprivation), no procedure for compensation is constitutionally required Davidson v. Cannon (1986): negligent failure to protect an inmate who feared violence from another inmate; the P sued for violation of liberty rights under PDP the 14 th Amendment; the Court extended Daniels and held there was no deprivation because it was negligent Rules Lack of care simply does not approach the sort of abusive government conduct the DP Clause was designed to prevent Just asking for state remedies but there’s no deprivation of a liberty interest, so the state doesn’t have to provide ANY remedy Importantly, though, in its final statement, the Court adds substantive due process and eliminates negligent deprivation of SDP as an option for a constitutional violation Other Opinions Brennan (dissent): recklessness or deliberate indifference would state a claim here; the record suggests this could’ve been recklessness Blackmun and Marshall (dissenting): he had no means of self-protection; the officials had a duty to protect him; the injury should play a role in the consideration here; would do a more case-bycase approach; even evidence of recklessness here; state doesn’t give adequate remedy—it gives immunity to them Stevens (concurring in judgments): DP contains 3 kinds of constitutional protections: (1) incorporation of BOR; (2) substantive component; (3) procedural guarantee; for the (1) can invoke regardless of state procedures; for (2) can invoke regardless of state remedy; but (3) is different— it’s not the deprivation that’s unconstitutional it’s the deprivation without due process or adequate procedures; the P doesn’t allege this here would just address whether state has adequate remedy, here; doesn’t think sovereign immunity makes state procedures unfair Other Issues If negligence is not a deprivation and intent can be a deprivation, what about something in between? Recklessness or deliberate indifference (dissents argue in Daniels that both are actionable); in Daniels, the Court deliberately doesn’t decide the issue Blackmun & Brennan: recklessness is actionable under the 8th Amendment, which is supposed to be more restrictive, so it should be actionable under PDP The lower courts uniformly say that recklessness or deliberate indifference can constitute a deprivation; they limit the rule of Daniels and Davidson to negligent and grossly negligent conduct Formulations of DI/Recklessness: Coach K likes “we don’t give a damn” Whether negligence can ever be a constitutional violation We know it doesn’t state a claim under PDP and SDP Incorporated rights: lower courts haven’t been willing to find negligence to be a constitutional violation but the Supreme Court hasn’t spoken on the issue Daniels leaves this option open Note 6: lower courts haven’t been willing to find that other constitutional rights can be violated through negligence 1st Amendment: “abridge” implies something not negligent Free Exercise: “prohibiting” implies something not negligent Whether Parratt applies to deprivations of liberty or life (PDP) 50 Note 2: Lower courts find that Parratt applies to all PDP claims The Supreme Court seems to sign off on this in Zinermon—the whole Parratt doctrine is an application of Matthews v. Eldridge to cases in which there’s no possibility of pre-deprivation process SDP & Incorporated Rights and Parratt Majority in Zinermon adopts Stevens’ part in Davidson—why is PDP different? The deprivation itself isn’t unconstitutional; it’s the deprivation without due process For SDP, there are just some things that the government can’t do even if it does give you a hearing first (i.e. torture); the constitutional violation is complete when the abuse is inflicted and no amount of procedure will make it ok ^ same analysis as SDP; when the government violates a 4th Amendment right, for example, the violation is complete when the illegal search happens and the procedure is irrelevant and the violation is done When there’s PDP, it’s 2-part; the actual deprivation may be permissible (the loss is not what the Constitution protects against; it’s the loss without due process); the constitutional violation isn’t OVER at the time of the loss; you must wait until after you lack process because it’s necessary to constitute a violation Ways out of Parratt: the case only applied to (1) Random & unauthorized actions not pursuant to an established state procedure Logan v. Zimmerman Brush (1982): discharge and P claimed it was for physical handicap; P claimed it was a violation of the IL fair employment practice law and sought a hearing before the IL fair employment practices commission; under IL law, the commission has to have a factfinding hearing within 120 days (that didn’t happen); the company argued the commission didn’t have jurisdiction after the 121st day and the IL Supreme Court agreed; P argued the IL law violated his PDP rights (deprivation of property interest in the cause of action without due process of law) The Court held it was a denial of PDP pursuant to the established state procedure; it should’ve heard the claim before depriving him of his rights D argued that Parratt applies—negligent deprivation of property and he can go to state court and sue in tort; but P argues it’s different because the established state procedure The Supreme Court agrees with P—it’s not a Parratt case because P is not challenging a random and unauthorized act; P is challenging the established state procedure, the law on the books ***The law on the books is unconstitutional because it mandates a loss of property on day 121 with no procedure Given that it’s not Parratt, the Court decides whether Logan wins by applying Matthews’ 3-prong test! Individual’s interest: redress for illegal discrimination and ability to make a living (HUGE) Risk of error with state procedures: might have had a bad claim but it’s not like the s/l that’s designed to weed out stale claims; the probable value of a new or additional procedure (HUGE) Government’s interest: not significant Hudson: Logan is different from Hudson because in that case it was a state actor, not the State; there was nothing wrong with the law on the books; the law on the books in Hudson allowed shakedown searches but nothing on the books authorized the destruction that was the basis of the claim; it was purely attributable to the state actor’s random departure from proper procedure (2) The state only provides DUE process for random & unauthorized deprivations if there’s an “adequate” remedy Argue the state remedy isn’t adequate Zinermon BIG ISSUE: is all the world either Parratt/Hudson or Logan? One might argue that if the state had more process, things might’ve turned out differently SPECTRUM Random & Unauthorized [Parrott/Hudson] Zinermon Pursuant to Established State Procedure OR Custom w/ the Force of Law [Logan] Zinermon v. Burch (U.S. 1990) Background 51 Determining when a P states a PDP claim or when a P cannot state a PDP claim because the state provides all the process that is due: The Court in Parratt & Hudson, when a state actor randomly & unauthorizedly deprives someone of an interest, the state cannot anticipate and provide pre-deprivation process, so the only process that is due is post-deprivation (in the form generally of a tort remedy) This does not apply when the P challenges the law on the books—when the people who are in charge of setting process, set a process that when followed will result in a deprivation without proper safeguards, then the law on the books is no good; the P can challenge that under § 1983; the Court will then apply Matthews balancing test; the key to Logan is that the P is attacking the official procedure/what the state says should happen—saying that when the state actor follows this procedure, the person is deprived of their interest without adequate process Zinermon: *** adds custom with the force of law to this category (an Adickes claim) The issue that comes up: whether the entire world of DP is either Parratt or Logan or whether there is a middle ground: the Zinermon majority and dissent are divided on this; the majority says the world is 3 parts; the dissent says the entire universe of DP is 2 parts (either Parratt or Logan) Now the issue is determining the scope and meaning of the “middle ground” Facts: P admitted to hospital “voluntarily” after signing certain forms; he was picked up and acting crazy; they gave him some drugs, so he feigned competency; they got him to sign forms so that he could be admitted pursuant to the procedures of a voluntary patient; his claim is that the hospital knew or should’ve known that he couldn’t give informed consent; he wanted the procedures afforded to patients admitted involuntarily and that by failure to do so he was deprived of a liberty interest under the 14th Amendment Issue: Whether Parratt necessarily means that Burch’s complain fails to allege any deprivation of due process because he was constitutionally entitled to nothing more than what he received (post-deprivation state tort remedies) The Court held that Parratt & Hudson don’t apply This is not a Logan case He is challenging the entire sequence of events but he’s NOT challenging the law on the books there’s nothing facially wrong with the FL procedures; it’s fine to have someone who’s competent to sign themselves in and that the procedures in place for involuntary commitment are fine He’s saying that if the law were complied with as written, then there wouldn’t be a deprivation of liberty without due process; the Court does a narrow construction of Logan (footnote 3, p. 205) The Court also says the P is NOT claiming that the hospital is engaging in a custom or practice that has the force of law This would be an Adickes claim—if P were saying that nobody followed the FL procedure and so the custom of admitting people was to force everyone at gun point to sign the admission forms, even if everyone knew they were incompetent, then you would challenge the custom under Logan because this would really be the law The Court says this issue is not before it He is claiming that Ds should’ve known or knew that he was incompetent: he’s either saying the doctor is incompetent or lazy or the doctor intentionally acted to deprive him of his rights; he’s pointing to the STATUTORY SYSTEM that allows the doctor to do what he’s done the doctor has broad power to sign people in and there is no process in place for making sure that someone really is competent There is something problematic with the law but not saying that it’s unconstitutional—if the doctor followed the FL statutes as written, there would be no constitutional violation; if you apply Matthews to the FL law, you won’t end up with the result of unconstitutionality If not bringing a Logan case, does that necessarily mean that it has to be Parratt? First, the Court says that Parratt can apply to liberty deprivations In other words, if not challenging the law on the books, must the actions of the D be necessarily random & unauthorized; the Court says NO! It isn’t necessarily a random & unauthorized deviation from the law on the books There is a middle ground (it’s neither Logan nor Parratt) Parratt & Hudson are merely applications of the Matthews test to situations in which one of the Matthews variables is negligible—the value of pre-deprivation safeguards [p. 210, “Parratt is not an exception to the Matthews balancing test] 52 So, the Court has to figure out whether the value of pre-deprivation safeguards is negligible; is this a case where the state could do something? FIRST, analyze the RISK (“We must ask whether the pre-deprivation procedural safeguards could address the risk of deprivations of the kind Burch alleges”) here the risk is that incompetent people will present as competent and sign forms when they can’t really give consent (this risk is HIGH given the nature of mental illness) SECOND, as whether the pre-deprivation safeguards would have any value or whether there is a process that the state could put in place to guard against the risk: focusing on the nature of the procedural scheme and the problem—the doctor has the duty or responsibility to determine and has the RIGHT to deprive someone of their liberty! He’s the gatekeeper; when the state gives the doctor this power, he also has the concomitant duty to see that no deprivation occurs without adequate procedural protections along with the delegation of power is a responsibility of ensuring that the criteria for exercising that power are met It may not be unconstitutional to have this system but if the state does give him this broad power, then the state’s necessarily also giving him the responsibility of making sure that he’s exercising that power when he is supposed to be exercising that power The doctor can’t say what I did was totally unauthorized; he has some responsibility to ensure that he is exercising the power correctly [p. 213: “It may be permissible …”] It’s the abuse of broadly delegated, uncircumscribed power to effect the deprivation; the abuse is by not taking steps to make sure that he’s exercising the power to deprive in appropriate cases (broad delegation & a specific risk of the type of error that occurred); it’s the combination of a broad power and a very foreseeable risk! The Court says Parratt doesn’t control for 3 reasons This is not unpredictable: that someone is mentally ill will be willing to sign the form even though they’re incompetent Pre-deprivation process is not impossible: you know at which point the loss will occur; statutory procedure in place telling the doctor to admit competent people the state could put process in place at the admission to make sure that doctors are determining whether the patient is competent; the hospital failed to ensure compliance with the FL statutory standard Dissent: ^ isn’t this a challenge to the law on the books? In order to state a PDP violation, P must allege some culpable state of mind (deprivation = some intent or recklessness), thus if you introduced more procedures, wouldn’t the doctor STILL ignore it? The majority: just thinking the doctor will flout the procedures is not enough; the Court thinks the doctor is deterrable (this isn’t like the guard in Hudson who had some vendetta; bent on revenge) this is the fundamental disagreement between the majority and the dissent This is not unauthorized conduct: the state didn’t authorize the doctor to do exactly what he did BUT the state delegated power to effect the deprivation complained of (the guard in Hudson had no right to ruin the prisoner’s non-contraband items); here, the doctor did what he was authorized to do without heeding the possible way of preventing such a loss The Court divided DP cases into 3 parts (1) Logan/Matthews: person challenging the law on the books; when people do what the law tells them to do, that results in a deprivation of life, liberty, or property without due process; seems to also reach custom/practice (2) Zinermon: law on the books when followed literally doesn’t mandate a constitutional violation but that law has a character, and from a combination of factors (broad discretion, predictable error, and abuse), it makes deprivation foreseeable; this means that the action is not random because it’s predictable; and the state can provide pre-deprivation relief by narrowing the doctor’s discretion (3) Parratt/Hudson: challenging a person’s random & unauthorized deviation from the law on the books; the state can’t prevent such random acts, so the DP only requires post-deprivation relief Dissent: The world is either Logan or Parratt; the crux of Matthews are the procedures necessary in the average case, if the doctor doesn’t know whether people are competent or not, then it’s the average case and you should apply Logan; but Parratt recognizes that people might deviate from the normal case, and those victims need post-deprivation relief 53 The P is arguing that the state procedure is defective and perhaps unconstitutional because it is giving such broad power to the doctor (Logan); if not The P is arguing that this is unauthorized (Parratt) ***We shouldn’t even have 3 parts Also arguing that this is unworkable and confusing [how do you define this middle ground?]; how to tell when a delegation is too broad? It’s hard to distinguish this from a case like Hudson certainly the guard in Hudson had the power to confiscate some of the stuff he found; one can predict when a guard is a searching a cell, the guard might take material that he can’t take and the state could’ve done something, like videotape the searches BUT no one suggested that the risk is big enough there When is the delegation too uncircumscribed? When is the risk predictable enough? State of mind [how do you square the idea of being able to prevent improper losses by putting more process in place with the state of mind requirement of DP cases; negligence doesn’t reach the level of a deprivation]: if you take the complaint seriously, Burch has to say that the doctor acted recklessly or wantonly, so he would be just as bad with more procedures Can you deter recklessness? Problems Easter House: facts—Easter House = adoption agency; the operating license is due to expire, so they apply for renewal; the licensing rep recommends renewal and forwards this to the main office; then there’s a conspiracy to deny the license based on personal problems with the adoption agency—the director of Easter House after the rep recommends leave on unfriendly terms and gets in touch with the people in DC and explains that the agency shouldn’t get renewed and that she’s going to open a rival adoption agency; allegation—through her complaints, she convinces the agency to hold her renewal of Easter House and to send through really quickly her competitive adoption agency; there are procedural irregularities with holding up renewal even though it was originally approved; approving competing agency really quickly; making them show compliance just screwing with them all attributable to a conspiracy between DC office and the head of the competitor adoption agency [assume there’s a deprivation of property here] ***One of the first attempts to apply Zinermon on a circuit level and it’s still cited a lot Claim: the head of the DC office has deprived EH of its operating license without due process because the department didn’t issue the license even though the justifications for it were present Issue: Is it Parratt or Zinermon? Whether actions were random & unauthorized or too broad of a delegation of power to the agency absent sufficient guidance? P argues it’s Zinermon: law on the books not unconstitutional; the agency failed to apply the law on the books in a manner that deprived P of property without DP; the state gave the head of the agency too much discretion to take away the license; it’s a predictable risk that can be deterred D argues it’s Parratt: no allegation of PDP case because this was random & unauthorized; so long as there’s a state remedy, no § 1983 claim Who wins? 7th Circuit found it was a Parratt/Hudson case relying on the fact that there was a CONSPIRACY, not predictable, and not something the state could do anything about Key facts Conspiracy Broad discretion (going for it being a Zinermon case)—if the statute said renew licenses in “appropriate situations” without defining what’s appropriate BUT if it sets out an ordered renewal process and the agency refuses to abide by it, it’ll be hard to use Zinermon San Geronimo: facts—case arising from development project in PR; SBGP purchased land near a fortress to develop; the project was controversial because there was a fear that it would damage the fortress; the permit administration suspended the project for 2 months without a hearing, invoking a provision of PR law that it can suspend projects without a hearing if there’s an emergency; a threat to health or safety; otherwise, there needs to be a full hearing The PR Supreme Court found there was no emergency; § 1983 suit filed, claiming it was deprived of the property because loss of ability to develop for 2 months The court said it was a Parratt/Hudson case; there was no unfettered discretion or uncircumscribed power; there was guidance in place (health or safety) and the general foreseeability that people might stretch it is not enough to meet the predictable error idea from Zinermon; the question is whether there is a specific and high risk; there was no additional process that’s practical; you MUST leave leeway for emergency situations; can’t delineate a list because will inevitably miss something 54 ANALYSIS Start with Logan: look at law on books and determine whether it’s permissible; it’s applying Matthews to the law on the books and whether following it leads to a deprivation without due process There’s a line of authority that in cases of emergency, the state can first act and then provide DP (emergency cases) Then determine whether it’s random and unauthorized action OR a case of broad discretion and predictable and preventable abuse Look at whether it’s predictable that this will be invoked when there is no emergency (you could argue that it’s not predictable when it delineates threat to health/safety OR you could argue that it’s predictable that people will stretch the term “emergency”) Ezekwo: medical student; brochure on first day of residency said everyone would be a chief resident in their third year; she had issues with her supervisor; in her third year, they changed their policy to pick chief residents based on merit only ***Issues like this come up a lot—Giving broad power of delegation to someone and not putting any limits to tell the person how and when to deprive; broad delegation of uncircumscribed discretion that makes erroneous decisions predictable ANALYSIS Logan: look at the system and determine whether it is followed to the tee and whether if so, that’s unconstitutional; if you apply Matthews to the law on the books, is there a violation? Could be so broad that it would have a risk of erroneous deprivation, thus it’s unconstitutional But no one is arguing that there’s a constitutional problem with letting the head doctor determine who’s chief resident Is it Zinermon or Parratt? Do you see the doctor as a rogue bent on denying her the position? Zinermon: broad power because there doesn’t appear to be an external constraint on how the chief resident is decided; combined with a right to effect a deprivation with no guidance the circuit adopted this argument: it was a deliberate act within the delegated authority and the situation was well-suited to process Waln: principle having power to deprive students of a property interest; focus on the power the specific person has Bogart: woman rescued animals but had a lot in her mobile home; a vet and deputy sheriff got a search & seizure warrant after hearing from the humane society, didn’t tell the judge of plans of vet to euthanize them; and then euthanized them; SC law provided that rescue of animals—care for them until a hearing, otherwise humanely dispose of them; woman sued for DP violation We know pets = property for DP purposes; not arguing that the law on the books is wrong; HERE, the law did provide for a hearing and this was NOT followed, so this is Parratt they didn’t have authorization to euthanize the animals immediately; the statute is pretty specific Under color issue with suing the vet: joint participation with deputy after knowing the vet’s plans (Dennis v. Sparks and Adickes); there must be some meeting of the minds or joint knowledge 4th Amendment claim: problem is that the SEIZURE was with a warrant; you’d have to argue that the killing was an additional seizure and that will be really difficult Ieyoub: woman’s car seized; charges dropped; they wouldn’t release her car so she filed state tort charges; the prosecutor doesn’t file a forfeiture proceeding until 3 years after they’ve gotten the car! This is Zinermon: it’s a very broad delegation with no limits—there’s no time limit on the prosecutor in deciding what to do (to file for forfeiture or to give the car back); it’s very easy to put a procedure here to remedy the problem! If the statute said you must file within 4 months and the prosecutor didn’t, then it would clearly be a Hudson case Summary of Zinermon: § 1983 PDP action is barred if the state has adequate post-deprivation remedies and 3 conditions exist: (1) deprivation was truly unpredictable or unforeseeable; (2) pre-deprivation process would’ve been impossible or unable to counter the particular conduct; (3) and the conduct must’ve been unauthorized in the sense that it was not within the officials’ express or implied authority (Stotter v. Univ. of Tex.) Is the rank of the officer relevant? If the state actor takes the action, then it would be random & unauthorized (Parratt) If the State (the people in charge of putting procedures in place), is it something the state is responsible for? (Logan) 55 Whether there are some people who by nature of their position ARE THE STATE Easter House: head of the agency, one making procedures: this didn’t fly because the agency made the procedure that told him what to do San Geronimo: the governor was involved but the court didn’t find enough action by the judge; but if the governor did tell them what to do, the governor is the state and by definition this isn’t random and unauthorized (CONCURRING OPINION) ***There is a circuit split on this issue This also ties in with municipal liability Some people are municipal policy-makers on behalf of the municipality some cases where those people are necessarily not acting in a random and unauthorized fashion because their decisions ARE state policy Municipalities: only liable when their policies or customs cause the violation Town of Castle Rock v. Gonzales (U.S. 2005): no SDP obligation to provide public services such as police protection; what about state law giving property interest in protection? Here, there was a restraining order against a dad; the woman called after their children were abducted by him and the police didn’t really do much to get the children (even though the restraining order said they HAD to enforce it); they were killed by their father; the Supreme Court held that there was no such property interest in such protection derived from a restraining order (reluctant to make DP a font of tort law) SDP/PDP and Parratt/Municipal Liability No SDP case because of DeShaney PDP case the Supreme Court held she had no entitlement to having the government enforce an order even if the statute is phrased in mandatory terms; it’s too inherently discretionary and says it’s just a way to get around DeShaney by couching it in PDP The 10th Circuit thought she stated a claim, that she had a property interest She had to get around Parratt—the court said there was a municipal custom of not enforcing restraining orders, so the law on the books was a violation of DP, thus making it Logan this is equating Parratt/Hudson with municipal liability Adequacy of Remedies Other way around Parratt: even if the action is random & unauthorized, DP still requires an adequate state remedy what makes the remedy adequate? It need not be as good as § 1983 but close (Parratt/Hudson); general state procedures that get you compensation are fine Even if the conduct is random & unauthorized, it’s NOT the end of the inquiry; the state must still provide adequate post-deprivation relief Circuits are in some disagreement but it’s clear that the state relief does not have to be as good as § 1983 (ex. state doesn’t have to provide punitive damages); there just needs to be some general ability to get compensation (tort, replevin, worker’s compensation, administration procedure, etc.) General procedural requirements don’t make relief inadequate (ex. if P misses a statute of limitations, it doesn’t mean there isn’t adequate relief; ex. notice of claim requirements don’t make relief inadequate) Immunities: tricky question as to whether the state having immunity means that there’s inadequate relief because the P can’t bring the suit Just claiming an immunity defense doesn’t mean relief is inadequate If there’s an established defense that D could raise precluding relief: Davidson v. Connor: NJ statute said there was NO liability of state officials for an injury one prisoner inflicted upon another, thus there’s no possibility to get tort relief in NJ against prison officials who didn’t react to the prisoner’s note saying he was in danger does this mean relief is “inadequate”? The Court didn’t decide that issue! Concurrences Blackmun: can the person get relief? That’s the primary question; since the person couldn’t get relief, the remedy is inadequate (***majority view) Stevens: is the state system fair? Thinks the system here denying compensation was fair Facially adequate remedies but not adequate in practice Examples Systemic delays (Ieyouab) not moving to forfeit the car; the 5th Circuit said they treated it like Parratt and found no adequate post-deprivation remedy because of state delays; the failure to institute 56 legal process means that the state system wasn’t responsive; then the court withdrew the opinion and treated it like Zinermon Other cases find that severe delays or systemic problems can make a state remedy that is facially legitimate inadequate ***THE P HAS THE BURDEN OF PROVING INADEQUACY OF THE REMEDY Problems in Causation Generally Looks broadly at whether we’re dealing with state action Two ways it comes up Clear that the state has done something but not clear whether the state’s challenged action is really what caused the constitutional harm (Mt. Healthy) Not clear whether the state has even acted in any constitutionally relevant sense (Martinez & DeShaney) Mt. Healthy City School Dist. v. Doyle (U.S. 1977) Facts: School refused to renew a teaching contract for its employee; he was a high school teacher who is a loose canon and has gotten into trouble; he didn’t have tenure so the school could have not rehired him if they didn’t want to; (they couldn’t have chosen to NOT rehire him because of protected speech under the 1st Amendment) there were instances of him arguing and mistreating people within the school; he also sent a memo from the board to a local radio station and criticized it (this is the basis of his First Amendment claim) The Court held that he didn’t state a claim (no First Amendment violation) The ISSUE was whether they fired him for protected speech or because of all the past incidents District court: standard was whether the protected speech played a substantial role in the decision to not rehire him; if so, then P could make out a 1st Amendment claim ***The Court held this approach is wrong—the danger is that it can enable constitutionally protected conduct to make someone better off; the GOAL is that the person shouldn’t be worse off; if you do a bunch of stuff that you know if bad, you get yourself “First Amendment tenure” and do something that’s protected Rules: The 1st & 14th Amendment claims are not defeated by the fact that he didn’t have tenure—he has a claim if the decision to not rehire him was made by reason of his exercise of his constitutionally protected 1st Amendment right Whether speech of a government employee is constitutionally protected, balance interests of teacher in commenting on matters of public concern and interest of the state as an employer in promoting efficient services to the public To state a claim, the protected conduct must have played a substantial role in the decision to not rehire AND must show that the same decision would not have been made absent the constitutionally protected speech being made (this is taken from the EP context) P must show (1) conduct was constitutionally protected; (2) this conduct was a substantial or motivating factor in the decision; and then D has to show by a preponderance of the evidence (3) that the board would not have reached the same decision absent such protected conduct The burden shifts—it’s a “bouncing burden”; it’s the same in the EP context: P shows that the zoning was discriminatory and then the burden shifts to the town to show that it would’ve done this anyway Notes This idea comes up in cases other than employment, in any § 1983 case where the showing of a constitutional violation ultimately hinges on the motivation; the courts use the same shifting approach In prison litigation—a prisoner can’t be punished in retaliation for exercising his/her First Amendment rights; the prison would be able to say no, we would’ve done this no matter what; higher burden is placed on the prisoner Courts are stricter outside the employment context, though Also applies to EP claims Martinez v. California (U.S. 1980) [precursor to DeShaney] Facts: parole board let a dude out, not observing formalities, when they should’ve known that he was a danger to the public; he ended up killing & torturing a 15-year old girl; procedure—her family sued the 57 parole board, claiming it was a 14th Amendment violation to deprive their daughter of life without due process of law CA has a statute that gives absolute immunity to the parole board Issues They can’t bring a state tort suit because CA grants immunity to the parole board They bring a § 1983 suit alleging a DP violation BY the board Mere existence of the immunity doesn’t deprive decedent of her life without DP—it doesn’t authorize killing people, thus the statute itself is not a deprivation Stevens’ concurrence in Davidson: the statute doesn’t deprive; even if you consider a tort claim a property interest, this state provision is rational; there’s nothing facially unconstitutional about the state’s tort scheme Rules: The Court held that the statute itself wasn’t a violation of DP: It didn’t authorize or immunize the deliberate killing of the girl; the statute didn’t deprive her of her life without DP (the statute was valid) CA immunity doesn’t control in the § 1983 case First inquiry is whether the P has been deprived of a right under the Constitution (Baker v. McCollan) here, she was not; the action of Thomas after 5 months of being released cannot fairly be characterized as state action; it was too remote a consequence to hold the parole board responsible This looks like a tort proximate causation analysis (the dude killing her was unforeseeable and an intervening cause) It’s asking whether the STATE has deprived the decedent of her life without due process (DP Clause: The state shall not deprive) ***THE KEY is that it wasn’t the state who killed her and the parolee wasn’t a state actor; it was merely a private person killing a private person BUT, the state let him out this is the proximate cause analysis; the state played a role but it was “too remote a consequence”; there wasn’t a “special danger” to that girl specifically and it was 5 months later (sounds like Tarasoff v. Board of Regents) It’s NOT importing tort law but it is putting a causation limitation on § 1983 The Court doesn’t set out what analysis is here, whether it’s tort law or something more rigid; it is setting up the idea that there’s not a constitutional violation just because the state did something that plays a causal role (there needs to be a tighter link) Notes This is a state court § 1983 case against the state by name—can’t do this anymore! (in either state or federal court) Footnote 7: can bring § 1983 claims in state court (there’s concurrent jurisdiction); TN at one time didn’t allow this but they now do SDP in state court: does the state’s immunity operate as a defense? Footnote 8: No, because of the Supremacy Clause (it’s a federal cause of action so the state law can’t define the contours) Townes: the search in violation of the 4th Amendment wasn’t the cause of damages stemming from conviction because the state’s denial of the motion to suppress was an independent, intervening cause (the original search wasn’t the cause of the injuries that happened later) Notes Martinez is the backdrop for DeShaney; the latter doesn’t overrule it but builds on the idea and focuses it; the harm inflictor is not the state actor Negative and Affirmative Rights Generally The issue, broadly conceived, is about causation—whether the state ultimately CAUSED the harm; DeShaney deals with cases in which the person who actually inflicts the harm is not a state actor; the argument is that the state was SOMEHOW responsible for what the killer did by failing to protect the kid The Court emphasizes that the state has no duty to protect (DP just protects against abuse of state power, not abuse at the hands of private actors) so in that case, the state didn’t cause the harm and has no duty to prevent the harm There are soft spots Equal Protection 58 “Other similar restraint” (affirmatively depriving someone of liberty and not allowing them to fend for themselves) State-created danger DeShaney v. Winnebago Cnty. Dep’t of Social Servs. (U.S. 1989) [huge § 1983 case—lots of lower court litigation building on this] State officials had strong evidence that boy was repeatedly subject to beatings by his father and didn’t do anything to take him out of the home; they had him in state custody and then brought him back home; he was beaten and now is profoundly retarded; procedure—him and his mom sued employees of the DSS for a deprivation of his liberty in violation of DP (SDP claim, claiming that their indifference shocks the conscience and caused his death) under § 1983; the Court rejected their claim under § 1983, holding that the state’s inaction was inadequate to sustain the claim Analysis You’d think after Martinez, the focus would be on causation but it wasn’t the Court looked at whether this is a case that even deals with STATE ACTION at all; whether the state has done anything constitutionally relevant and whether the state had a duty to act Due Process: this is not a case where the state affirmatively hurt someone; it’s just a case of it failing to do anything to protect people; there’s no obligation on the state to protect people Rules: Theories Too attenuated No affirmative constitutional duty Nothing in the DP clause itself requires the state to protect the life, liberty, and property of its citizens against invasion by private actors; its language cannot fairly be extended to impose an affirmative obligation on the state to ensure that those interests do not come to harm through other means ***The focus of the DP clause is to prevent affirmative abuses of the STATE power; to prevent the state from acting in an arbitrary action that harms people Exceptions: cases pointing in the other direction (SDP and 8th Amendment cases) CUSTODY (prisoners, involuntarily committed persons, and other restrictions; state-imposed limitation on the person’s freedom to act on his own behalf; the state’s affirmative act of restraining the individual’s freedom to act on its own behalf, not its failure to protect his liberty interest against harms inflicted by other means) Duty to provide medical care Duty to provide reasonable services to involuntarily committed patients ***The difference is that the Court can point to an affirmative act of the state— depriving the person of his/her liberty, so the state has a concurrent responsibility to care (important quote: “In the SDP analysis, …” (p. 238)) STATE-CREATED DANGER FN 9: Case might be difference if they placed the boy in a foster home run by the state’s agents Dissent (Brennan): thinks the state did do something to put him or keep him in this predicament; they delegated the responsibility to DSS—effectively giving the citizens only a duty to report and then do nothing; puts it within Estelle Our baseline should be ACTION; thinks the state funneled everything to DSS—the doctors can’t do anything in the ER on their own; they have to go through DSS; by channeling the complains to the DSS, the state acted affirmatively and imprisoned Joshua by making him at the mercy of the DSS Majority counter: it’s a FREE WORLD and the state has no obligation to prevent people from coming to harm Dissent (Blackmun): the majority characterizes this as a case they’ve seen before but he says this is an open question; it is too formalistic of an approach SOFT SPOTS in the case Other similar restraints: it has to be a deprivation of liberty but not just through incarceration or institutionalization (ex. foster care) State-created danger: the state may have been aware of the danger he faced but they didn’t CREATE the danger nor do anything to render him any MORE VULNERABLE (if the state intervenes & changes things around, there may be state action) 59 Collins v. Harker Heights (U.S. 1992) [public employment] State employee dying of asphyxia after working in a manhole to fix a sewer line; sued city for failure to train employees and provide safety equipment; the Court rejected the SDP claim relying on DeShaney The DP clause does not impose on the government employer a duty to provide a safe working environment (not denied liberty after voluntarily accepting a job with the city); failure to train = employment relationship and that’s subject to state law There was no allegation that the state made him WORSE off (if it were his boss retaliating for something, deliberately giving him a faulty mask, that would be a SPECIFIC ABUSE of state power; if the state gave him a dangerous job in retaliation, same thing) This is just an unsafe workplace claim—no duty under SDP; just a tort case—there’s no state action in any relevant sense There is no deprivation of liberty in hiring him, not in custody on the job (threat of losing job isn’t enough); it’s just a bad management decision and the Constitution isn’t a guarantee against this Notes & Questions Equal Protection: 1983 cases that arise out of non-response to domestic violence calls; the argument is that the state has a 911 system in place but police don’t respond to domestic violence calls but respond to other calls; the person brings a 1983 suit saying that the state’s failure to respond caused the person to be beaten the state will argue that there is no duty to rescue the person or put a 911 system in place (it has a system in place though!); the argument is now Equal Protection because it’s a claim of gender discrimination DeShaney: footnote 3—the state cannot selectively provide services; if the state has a 911 system, it can’t selectively decide to discriminate against certain groups Watson v. Kansas City (10th Cir. 1988): No constitutional right to police protection but the state cannot discriminate in providing such protection Ricketts: For gender bias claims, must show intentional discrimination; EP requires an intent to discriminate Nabozny: high school boy gay & beaten and school officials wouldn’t do anything; he brought a 1983 suit; the school argued no duty to protect under DeShaney and the 7th Circuit said it wasn’t a DeShaney case because the claim was under Equal Protection (if he were a girl suffering the same harm at the hands of boys, the state would’ve intervened); they didn’t intervene for discriminatory reasons; so it’s a way to get around DeShaney ***Equal Protection is a way OUT of DeShaney but it’s hard because it requires an intent to discriminate; for that reason, people usually attack the 2 soft spots Foster Care & State Custody: Henry A. v. Willden (9th Cir. 2012)—foster children can bring SDP claims challenging their placements and denial of medical care under the special relationship and state-created danger exceptions State-Created Danger: This is the argument to avoid DeShaney Bright v. Westmoreland Cnty. (3d Cir. 2006): state released a pedophile into the community and is in touch with his 12 year old victim; the family of the victim notifies the police and asks them to revoke his parole; the state doesn’t do anything and the pedophile kills the victim’s sister to retaliate against the family; they bring a 1983 claim and the state argues DeShaney; the 3rd Circuit agrees with the state, giving an approach 4 elements to state-created danger claim: (1) harm ultimately caused was foreseeable and fairly direct; (2) state actor acted with a degree of culpability that shocks the conscience; (3) relationship between the state and P is such that the P was a foreseeable victim of the D’s acts or a member of a discrete class of persons subject to the potential harm and not a member of the general public; (4) state actor affirmatively used his/her authority in a way that created a danger to the citizen or that rendered the citizen more vulnerable to danger than had the state not acted at all (requiring affirmative acts) ***(4) is the KEY: the state actor must affirmatively act and use his authority that created a danger or rendered him more vulnerable (here, the state merely failed to act) Kennedy (9th Circuit): telling police that a kid molested their daughter; the police ASSURE the Kennedys that they won’t talk to the Burns unless if they tell them; they talk to the dude and the Kennedys find out; the police say they will patrol the area and they don’t; the dude breaks in and kills 60 the parents; they bring a 1983 suit arguing state-created danger, state argues DeShaney; the court held that the state DID act in telling the Kennedys not to worry and that they would patrol the area; they affirmatively acted to make them worse off because they didn’t have to do anything for themselves ***Kritchevsky thinks these cases are in TENSION Problems Generally Recurring mold of these cases: the cops swoop in, rearrange things, and then leave, making people worse off Lower courts tend to find that they state a claim in these instances If the cops just show up and DON’T rearrange things, then it’ll usually be different and the courts won’t hold them liable Wood v. Ostrander (9th Cir. 1988): Wood is riding with Bell, who the police arrest for drunk driving; the officer calls for a tow truck and tells Wood that she needs to get out of the car and walk home; they wouldn’t give her a ride; she hitchhikes and gets raped; she brings a § 1983 suit; arguments Cops argue DeShaney—no duty to protect P argues: state-created danger because the police have taken her from a position of relative safety and created the dangers that she faces being alone on the road or other similar restraint by rendering her unable to take care of herself; they aren’t taking her into physical custody but they’ve ordered her to get out of the car, so they assumed physical control over her movements and then required her to be stranded on her own Problems with her arguments: the state’s actions are falling under SDP, thus the conduct has to satisfy the culpable state of mind requirement—something like shocks the conscience The 9th Circuit allowed it to survive SJ, that she DID state a claim; the state restrained her by taking control of her movements and then putting her in a position of danger by taking her from one place and putting her in a more dangerous place Kneipp v. Tedder (3d Cir. 1996): couple walking home late at night; they were drunk; police stopped them and took the dude into custody; the dude assumed that the cops would see his wife home; they didn’t and left her to walk home; she fell and suffered brain damage; the court held she stated a claim under the state-created danger, by leaving her without a protector by intervening and changing things around (she had her husband until the cops intervened) School Context Stonekick: high school student reports to school that a teacher is sexually harassing and abusing her and other make complaints; the school does nothing and she brings suit; the school says DeShaney the teacher is a state actor, so DeShaney does NOT apply DeShaney cases ONLY come up when the person inflicting the harm is NOT a state actor Morrow v. Balaski (3d Cir. 2013): school not protecting students from other student bullies; the Morrow girls are victims of bullying and threats; the school suspended the bully and twice let her back in; the bully is adjudged delinquent and the school still lets her back in; the girls finally switch schools because their school won’t do anything; we know the bully is NOT a state actor, so it raises DeShaney Issue: whether being in high school is a “similar restraint” there are limits on the rights of one to defend themselves BUT, the court held that there’s no duty to protect high school students; the court said it isn’t anything like custody even though they have to go to school and have limits on them while in school it’s not a similar restraint It’s different from incarceration because the kids can go home to their parents; their parents can transfer them to another school; they have access to the “free world” unlike prisoners The Ps said the school did to something: Readmission of the student after suspension and no contact order BUT: the state gave Joshua back to the parents in DeShaney and that didn’t change things there Responsible for the student getting on the school bus by not keeping her off BUT: this is pure inaction 61 Doe v. Covington County (2012): grade school, check-out policy put in place; the school didn’t check in one instance where a man came to check out a student and raped her; the court held that the state DID to something, it created a policy that reassured parents that they were protecting their children while at school; the affirmative act created the danger! BUT, the 5th Circuit reversed, holding that DeShaney applied because the state wasn’t aware of any specific risk Cornelius v. Town of Highland Lake: town clerk alleges she was abducted by prison inmates who were given work assignments in the area; the state failed to assure that they weren’t out in the community and failed to supervise them when they were They were on work assignment There was supposed to be supervision ***The town still had custody of the harm inflictor! The state has affirmative control over the harm inflictor and then puts that person in a position to harm someone, the argument being that the state created the danger the court adopted this! DeShaney didn’t apply because it was a state-created danger Lemacks overrules this on a different theory: public employment theory; there’s NO duty to create a safe work environment (applying Collins); the state has no obligation to provide a safe work environment; if the workers were there to punish the clerk, then the state would’ve affirmatively acted to increase the harm Nishiyama: pre-DeShaney; raising an important issue—the county has an inmate who’s a trusty and they let him drive the cop car around; he pulls over a girl and kills her; the question is whether she has a claim against the county (Dickson county); here, the harm inflictor is a prisoner but still an inmate and the cops affirmatively put the cop car in his hands One argument: affirmative action by giving him a weapon but it’s not a total conspiracy—not a good argument The 6th Circuit found that she stated a claim and it didn’t fall under Martinez: it was different because there was ongoing custody over the harm inflictor as opposed to Martinez where the dude was paroled; the county officials knew of the risk when they were called and told that the dude was pulling people over and stopping them Would this survive after DeShaney? The state affirmatively acted when they told the dude to drive back; it’s ongoing state action, they allowed the car to go on the streets in the hands of a convicted felon but you still need a state of mind and proximate causation! Real issue: does Martinez survive DeShaney? It’s not hard to envision cases where the state has acted but still need proximate causation If you get around the state action/proximate cause, you still need a state of mind! (look to Lewis and the external constraints, something like M&S or DI) State of mind D must have acted with a sufficiently culpable state of mind; the action must shock the conscience deliberate indifference OR competing obligations 6th Circuit rule from Claybrook v. Birchwell: if state officials have reasonable opportunity to deliberate various alternatives prior to electing a course of action, their actions are conscience-shocking if they were taken with deliberate indifference towards the plaintiff’s federally protected rights; if it’s a rapidly evolving, fluid, and dangerous predicament which precludes the luxury of calm and reflective pre-response deliberate, the action shocks the conscience only if they involved force employed maliciously and sadistically for the very purpose of causing harm rather than in a GF effort to maintain and restore discipline Avoiding Collins: showing either intentional injury or arbitrary conduct intentionally designed to punish someone SELECTING THE PROPER DEFENDANT Generally Assuming we can make out a claim, we want to sue someone who will get us relief Potential defendants Individuals: an individual, a person, who one is suing in his or her official or individual capacity; the party is the one by law that is the D who would have to pay; suing for that person’s misdeeds for out of pocket damages; indemnity is irrelevant (private K) Individual immunities: immunity from suit (absolute) or from having to pay damages (qualified) 62 Source of individual immunities: individuals immune from damages depending on their function; this has been incorporated in 1983 from common law Municipalities: cities or counties; agencies of local government (i.e. “City of Memphis” or “County of Shelby”) They are persons, so you can sue them by name They are only responsible for injuries caused by their policies/customs Source: creature of the courts’ reading of the statute & policies behind it; it’s a court-created concept that goes to the courts’ parsing of the language of 1983, talking about suing a person who “causes” another to be subjected—this is the statutory construction States: i.e. “State of Tennessee” States are not persons, so you can’t sue them by name You can sue state officials in their capacities, suing them solely as a representative of the state; using the suit against the individual as a root to getting to the state Source: combination of the 11th Amendment (not suing a state in federal court) and statutory construction determining that states are not persons Individuals: The Role of Individual Immunities Introduction Immunity: from being sued or from having to pay damages—common law origins Absolute immunity: you can’t sue them for acts within the function that gets them the immunity; examples from common law—prosecutors, legislators, judges, witnesses, and other participants in judicial processes (grand jurors and ALJs for Bivens actions); not subject to suit when acting in that capacity Qualified immunity: you can sue the person but they aren’t responsible for damages if they can show certain things about their action (Pierson, GF & PC); dependent on whether he should’ve known that he shouldn’t have done something It is only an issue when damages are sought, not other equitable relief, i.e. reinstatement Judges were immune at common law Other state officials had partial immunity (“good faith” immunity); can’t sue them if they act in GF and with PC What did § 1983 do with these immunities? The Supreme Court has held that it did not eliminate them; the immunities were so well established that Congress would’ve explicitly stated if it were abolishing them, thus § 1983 should be read against the background of common-law immunities Origin Pierson v. Ray (U.S. 1967): liability of officers & judge; the Court held the judge is immune under § 1983; rules Judges are immune from liability for damages for acts committed within their judicial jurisdiction, even when the judge is accused of acting maliciously and corruptly Police officers do not have similar absolute and unqualified immunity as police officers were not absolutely immune at common law; only immune if they act in GF and with PC Justifications Chilling judicial judgment Preventing threat of suit from influencing decisions Protecting judges from liability for honest mistakes Relieving judges of the time and expense of defending suits Removing an impediment to responsible men entering the judiciary Necessity of finality Appellate review is a satisfactory remedy Judge’s duty is to the public not to the individual Judicial self-protection Separation of powers Immunities are an affirmative defense Gomez v. Toledo (U.S. 1980): P needs to only plead D acted under color of state law and effected a deprivation of protected rights; P need NOT plead that the D is not entitled to a qualified immunity; D must do so as an affirmative defense; D can waive the immunity by failing to raise it, but it is usually allowed to bring it up late in litigation and when a D has properly raised the immunity defense, the P has the burden of showing a violation of a clearly established federal right Appealing denials of immunity 63 Immunities protect a person from having to stand trial, so the district court orders are usually immediately appealable collateral orders Johnson v. Jones: D who is entitled to invoke immunity may not appeal a district court’s SJ order insofar as that order determines whether or not the pretrial record sets forth a genuine issue of fact for trial A court can’t decide questions unrelated to immunity on immediate appeal A party can’t appeal a denial of SJ on qualified immunity grounds after the district court has conducted a trial on the merits Ds in state court who are not granted immunity don’t have a federal right to appeal Absolute Immunity Judges: Everything they do isn’t immune Stump v. Sparkman (U.S. 1978) Facts: P suing a judge for granting a petition by P’s mother to have her sterilized after deciding that she’s “somewhat retarded” for sleeping with older men; the petition is to hold the doctor not liable later for performing this surgery Procedurally: the judge is the only state actor here; this was pre-Dennis v. Sparks and the court held that the conspiracy allegation wouldn’t work The Court held that the judge IS IMMUNE from suit 2-prong analysis Jurisdiction Nothing in the FL statute or common law preventing the judge from granting this petition; there were rules re: involuntarily institutionalized persons might be subject to sterilization She was a circuit court judge of GENERAL jurisdiction, so nothing that excludes this sort of job Construing the jurisdictional question: BROADLY (there’s nothing that says she can’t), not narrowly (nothing that says she can); since the jurisdictional question is hard to decide we give the judge leeway; key question: whether the judge has acted in the clear absence of all jurisdiction (here, no, because nothing saying she didn’t have jurisdiction); “We agree”… (p. 259) Judicial act Whether it’s a function normally performed by a judge and the parties treated it as such/expected it as such Here, the parties came to him because he’s a judge and judges normally grant/deny petitions (not focused on the fact that this specific petition has never been granted by a judge) The Court imported immunities from common law (absolute and good faith (“qualified”)) Absolute to judges/prosecutors because of their intimate role in the judicial system & their often involved in deprivations of liberty; they need to decide controversial issues that can be rectified on appeal Dissent: there isn’t appeal available here, there aren’t parties; judges shouldn’t get immunities when the factors/policies that support immunity are absent Rules Judges/prosecutors don’t automatically get immunity purely because of their job—it depends on whether the action for which they’re being sued is the performance of the function that entitles them to immunity Judges of courts of superior or general jurisdiction are NOT liable to civil actions for their judicial acts, even when such acts are in excess of their jurisdiction, and are alleged to have been done maliciously or corruptly Jurisdiction: judge will be subject to liability only when he has acted in the clear absence of ALL jurisdiction FL statute: not anything in it or in case law prohibiting the judge from considering a petition of this type Due Process: a judge is absolutely immune from liability for his judicial acts even if his exercise of authority is flawed by the commission of a grave procedural error Judicial act: the standard is whether it is a function normally performed by a judge and to the expectations of the parties (whether they dealt with a judge in his judicial capacity)—here, it was because petitions are judicial actions 64 Dissents Stewart: This wasn’t a judicial act because it had never been done before; should have considered justifications for having judicial immunity Powell: Preclusion of all other remedies for the P here; shouldn’t sacrifice this person’s right just for the greater good Problems on Judicial Immunity Forrester v. White: probation officer under judge’s discretion doing things the judge normally does, like pretrial reports & recommendations on probation; she was discharged by the judge & claimed it was a result of sex discrimination; whether the judge is absolutely immune from the employment decision Jurisdiction not a factor here Judicial act Judge would argue—it’s an employment decision closely related to a judicial function and the employee was doing things that a judge normally does P would argue—this is executive; the nature of the act of firing someone is executive and the fact that a judge is doing it doesn’t mean it’s automatically a judicial act When the judge is performing the executive function of hiring & firing, he’s NOT acting as a judge and gets the immunities that executives get = qualified immunity Focus on the function & nature of the activity, not whom it is being performed by Mireles v. Waco: PD doesn’t show up in court as P; judge orders the bailiffs to “find him and ruff him up”; and P alleges that the judge deliberately and knowingly approved & ratified the acts; whether the judge gets absolute immunity Arguments: we look at function broadly (here, it was securing the appearance of individuals in the court room) but we can look at it as specifically what the judge did (asked them to ruff him up; judges don’t normally do this) If we look at it narrowly, judges will NEVER get immunity, so we must look at things broadly (reiteration of Stump) Jurisdiction: nothing here has deprived the judge over jurisdiction of the parties and the case Dude has stolen ID and gets arrested for something the thief does; the judge does 3 wrongful things: for analysis, break down the acts in to distinct parts Holds him in contempt with no bond (even though statutory maximum) is a $10 fine): if we’re focusing on the judicial act part, holding people in contempt is something judges normally do BUT the statute limits the judge’s power to hold people in contempt, so it’s a jurisdictional issue this was a case in his courtroom and he had jurisdiction to handle DUIs The 6th Circuit said he is not acting in the clear absence of all jurisdiction (just because he’s ignoring the statute doesn’t mean that he doesn’t have jurisdiction) He has absolute immunity here Changing the bond on the warrant: we know we have jurisdiction; changing bond is just like setting bond, so it’s a judicial act Telling the officers that the identity of the two men are one in the same: here, the judge might be acting more like an investigator—telling the cop who to go for and how to serve it; here, he gets the immunity of an officer Summary These are really fuzzy lines, but there are basic principles: Jurisdiction is a very broad concept of looking at subject-matter jurisdiction over the dispute; merely violating the rules of that jurisdiction doesn’t mean you lost it Look at function broadly without regard to the specific errors When the judge is doing an act that is inherently executive, such as firing someone or telling the cops how to do their job, the courts will not consider that to be a judicial act Non-judicial acts Stalking & sexual conduct Threatening coffee distributor of arrest if he doesn’t brew good coffee Prosecutors Generally Court has decided lots of questions on prosecutorial immunity; it’s similar to judicial immunity because prosecutors are absolutely immune for a lot of the same reasons that judges are: 65 Fear of shading their exercise of judgment Being scared of going after people for fear of being sued The system can deal with this stuff on appeal Issue: prosecutors work closely with the executive officers which makes it hard to separate them out when the prosecutor is acting as a prosecutor and when the prosecutor is acting as an aid to the cops Imbler v. Pachtman (U.S. 1976) [lead prosecutorial immunity case] Prosecutor gives false testimony & suppresses evidence; the Court held that prosecutors get ABSOLUTE IMMUNITY under 1983 for much of the same reasons that a judge does Rules The absolute immunity is limited to activities that are intimately associated with the judicial phase of the criminal process initiating the prosecution and presenting the state’s case/acting as the advocate of the state The Court left open the question of whether a prosecutor would be absolutely immune when performing investigatory or administrative functions we know they are NOT absolutely immune when performing these functions; they get qualified immunity Van de Kamp v. Goldstein (U.S. 2009) Informant giving information to cops; stated that he didn’t receive a benefit for this information; there was not system in place in the prosecutor’s office to share information about informants; the D sued the prosecutor’s supervisor for failure to establish procedures to communicate information about promises made to informants The P couldn’t sue the prosecutor on the case because he was clearly immune because he was presenting the case and the problem can be addressed on appeal Administrative acts are NOT entitled to immunity BUT the Court held this was NOT administrative because it was directly connected with trial conduct & required legal knowledge and the exercise of related discretion Policy: the court didn’t want Ps to be able to get around prosecutorial immunity so easily by just saying that it’s training or system management; it would be an easy pleading technique These are making legal decisions on setting up the prosecutorial function not something like firing someone Complaining witnesses: Kalina v. Fletcher (U.S. 1997)—prosecutor filed complaint with a certification of PC that it had accurate statements in it; the Court held the prosecutor was not entitled to absolute immunity for the CERTIFICATION because a competent witness could’ve done this (it was not a traditional prosecutorial function; a private person could do this) Prosecutors don’t receive absolute immunity when acting as complaining witnesses Here, he was immune for filing the information and seeking dude’s arrest ***Another reminder to look at each act separately Police investigation: Burns v. Reed (U.S. 1991)—woman claimed assailant broke in to her home; her children were killed; the cops thought it was her even though the evidence didn’t really indicate that—they didn’t have any leads and there wasn’t any support for the woman being the suspect; they wanted to hypnotize her to get a confession; they asked the prosecutor, Reed, if they could do this and he said YES The Court held the prosecutor was NOT immune for the advice re: hypnosis because it was in the INVESTIGATIVE phase of the criminal proceeding; he was entitled to immunity for presenting the false testimony at the probable cause hearing Acts Ok on hypnosis: no absolute immunity; intimately associated with investigation; there’s no evidence against her yet Saying, they probably have probable cause: trickier question: doesn’t get absolute immunity because it’s giving advice during investigative phase Arrest warrant with confession that wasn’t really a confession and the prosecutor didn’t tell the judge that: this is obviously prosecutorial; in eliciting testimony on behalf of the state to get a warrant, the officer is presenting the state’s case and that goes to the core of the prosecutorial function Investigation v. Prosecution: Buckley v. Fitzsimmons (U.S. 1993)—girl abducted and killed; found boot print in their home and investigated Buckley; evidence didn’t really point to him; prosecution hired expert known for fabricating testimony; Fitzsimmons was running for state’s attorney and asserted the existence of nonexistent evidence (saying we’ve got the guy and have evidence tying him to the crime) and employees arguing that he was innocent were forced to resign; Fitzsimmons lost and new prosecutor pursued and 66 presented false and perjured testimony; then someone else confessed to the murder; Fitzsimmons and others claimed prosecutorial immunity; who wins? Court focuses on acts: Statements at the press conference: not part of presenting the case; the problem is that the statements at the press conference don’t even violate a constitutional right! So the Court doesn’t even need to get to the immunity question; if there’s no constitutional violation, don’t worry about immunity Decision to prosecute: the testimony is fabricated but this is a decision of how to present the state’s case BUT it’s gathering evidence and investigative so no absoulte immunity Presenting the case with fabricated evidence: this becomes prosecutorial because even with the false evidence, the prosecutor is entitled to absolute immunity because it’s presenting the case Applying Buckley Whitlock v. Breuggemann (7th Cir. 2012): persons wrongly convicted of murder alleging attempts to frame them; the question of immunity hinged on factual disputes as to whether the nature of the action was prosecutorial; also noted that prosecutors aren’t entitled to immunity before he has PC Giraldo v. Kessler (2d Cir. 2012): woman looked like she was victim of domestic violence; police questioned her for a long period of time and she sued; the prosecutors claimed prosecutorial immunity; the 2d Cir said the approach to absolute immunity was an objective inquiry, whether a reasonable official in the position would view the circumstances as reasonably within the function of a prosecutor GF said it was a violation of her 4th Amendment rights; the Court held that the interview was part of the prosecutorial function; the prosecutor’s function is to determine whether to file the case and whether there’s enough information There was absolute immunity K thinks this court got it wrong, that this was clearly investigative McGee v. Pottawattanie (8th Cir. 2008): prosecutor not entitled to absolute immunity for violating SDP in obtaining, manufacturing, coercing and fabricating evidence before filing charges because so doing was not a distinctly prosecutorial function; argued that procuring false testimony is not a constitutional violation and its use at trial was immune Other Types of Absolute Immunity Legislative immunity Tenney v. Brandhove (U.S. 1951): legislators are absolutely immune when acting in a field where legislators traditionally have power to act; it extends to legislative aides and assistants involved in the legislative process (Aitchison v. Raffiani, 3d Cir. 1983) Lake Country Estates v. Tahoe (U.S. 1979): regional legislative bodies receive absolute legislative immunity Brogan v. Scott-Harris (U.S. 1998): local legislators are similarly immune; firing someone based on racial animus; the Court held that this function was NOT administrative and thus entitled to immunity; not looking @ motive but the function of the act; the budget was a discretionary, policymaking decision; the acts were legislative even if performed by an executive officer—officials outside the legislative branch are entitled to legislative immunity when they perform legislative functions Crymes v. DeKalb County (11th Cir. 1991): development/zoning decisions Witness immunity: receive similar protection to that of judges & prosecutors (Brisco v. LaHue, U.S. 1983); actions against them are infrequent Court: Supreme Ct. of Va. v. Consumers Union (U.S. 1980)—issuance and promulgation of rules of professional conduct; it can adjudicate questions of whether an attorney really did violate the Code & can be sanctioned accordingly; Court can initiate actions on its own, it can bring a charge against the attorney; issue: whether the different acts get absolute immunity Absolute immunity is a functional analysis Court looked @ function Promulgating code: absolute immunity because it’s a legislative function Adjudicating a dispute: absolute immunity because it’s a judicial function Bringing the charge: does not get absolute immunity because in determining we think there should be a proceeding against this person, the Court is acting as a complaining witness or a police officer (not prosecutor because they’re not filing the charges); this is executive and gets only qualified immunity Functional analysis: look at the function in determining the applicable immunity Prospective Relief & Attorney’s Fees Background: absolute immunity = immunity from suit, not just damages; whether this means that the persons who are absolutely immune are subject to injunction & declaratory relief 67 It depends on who you’re dealing with Legislators: state legislative officials are absolutely immune from damages AND equitable relief if taken in the sphere of legitimate legislative authority (Tenney v. Brandhove, U.S. 1951); they’re also immune from INJUNCTIVE RELIEF Prosecutors: prosecutorial immunity does not extend to injunctive and declaratory relief; prosecutors are rarely subject to injunctive relief because the Younger doctrine precludes federal injunctions against pending state criminal proceedings; do not have absolute immunity from INJUNCTIVE RELIEF; it’s hard to get the injunction anyway Judges: Pulliam v. Allen (U.S. 1984): can one get an injunction against a judicial officer who is continuing to do something unconstitutional Absolute JUDICIAL immunity does not provide protection against injunctive OR declaratory relief; it also held that § 1988 provides that fees & costs can be awarded to prevailing Ps in § 1983 actions even if the D is immune from damages (this includes judges); the majority didn’t think injunctions raised the same concerns as lawsuits; federalism concerns—but 1983 was enacted because state courts weren’t doing their job; § 1988 is available in any action to enforce a provision of § 1983 It relied on English common law and held there’s no inconsistency between injunctions and immunity AND the chill from injunctive relief is less from the chill of damages They were ALSO on the hook for fees because the party who sued was a prevailing party Dissent (Powell): suits for damages and injunctive relief present the same dangers to judicial independence; attorney’s fees promote increased harassing litigation ***This caused a big uproar Federal Courts Improvement Act of 1996 cutting back on Pulliam but did NOT overrule it: Congress amended §§ 1983 and 1988; § 1983, added, injunctive relief against judge in judicial capacity shall not be granted unless a declaratory decree was violated or declaratory relief was unavailable; § 1988, added, judicial officer shall not be liable for costs, including attorney’s fees, unless such action was clearly in excess of such officer’s jurisdiction The result is § 1983 the way it’s written today key: “except in any action brought against judicial officer for an act or omission taken in such officer’s judicial capacity, injunctive relief shall NOT be granted unless …” This doesn’t overrule Pulliam because there’s a still possibility of getting declaratory relief; it’s available if the judge ignores the declaration or it was impossible to get declaratory relief Also amended § 1988 to cut back on the possibility of fees more significantly: only available if the judges acts clearly in excess of his jurisdiction; where the judge would LOSE on the issue of immunity (could win on § 1983 injunction with judge still having immunity but wouldn’t be able to get fees) Other Officers with Judicial Immunity: parole officers? Bivens: 11th Circuit said Pulliam applies to Bivens actions Qualified Immunity Discussion This is an issue that comes up in most litigation; result is that executive officers can claim qualified immunity; big issue is what qualified immunity is when it really protects someone History: in the earliest cases dealing with immunities & 1983 (Pierson v. Ray), the Court said that police officers were immune if they acted in good faith and with probable cause—this idea was that there was a “good faith” immunity, that an officer acting subjectively in good faith could receive protection The Court recast the immunity defense in more rigorous terms in Wood v. Strickland Development Wood v. Strickland (U.S. 1975): officials who don’t have absolute immunity could be immune if they acted in GF; suit brought by high school students challenging semester-long suspension for spiking the punch; the standard called for both subjective & objective elements: for school discipline, officials are NOT immune if (1) he knew or reasonably should’ve known that the action he took within the sphere of official responsibility would violate the constitutional rights of the student affected or (2) if he took action with the malicious intention to cause a deprivation of constitutional rights or other injury to the student Immunity re: school board members the Court said they would get immunity unless 1 of 2 things were present They knew/should’ve known that what they were doing violated the Constitution OR Objective They acted with malice 68 Subjective The standard was a dual objective-subjective standard but there’s a problem with this if you’re a P suing someone know with the case, you’re going to allege in every case that the D acted with MALICE (it’ll be nearly impossible to resolve on SJ, just say it’s malicious, and it goes to the jury); but immunity then doesn’t really protect anyone from having to go through a whole trial in order to prevail; it might save someone from damages but the fear of litigation chilling people from exercising discretion remains Harlow v. Fitzgerald (U.S. 1982) [response to the problems in Wood; key immunity case]: the Court changed the Wood test it eliminated the subjective inquiry and applied the same immunity standard to ALL government officials exercising discretionary functions; this was re: senior aides/advisors to the President; it eliminated the subjective inquiry because this made the case go to trial (factual findings by juries); government officials performing discretionary functions generally are shielded from liability for civil damages insofar as their conduct does not violate clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known; looking @ objective reasonable of conduct, measured in reference to clearly established law (if not clearly established, not going to be expected to know he was acting against the law) This is a Bivens case but the immunity question is the same as § 1983 It overruled Wood and eliminated the subjective component because that ran against the policies of adopting immunity in the first place (chilling discretion) for immunity to work, it has to protect people from going through the whole lawsuit It can no longer be called “good faith” immunity The test is still the basic standard for qualified immunity: “governmental officials…” (see above) QUESTION: WHETHER THERE IS A VIOLATION OF A CLEARLY ESTABLISHED CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHT OF WHICH A REASONABLE OFFICER SHOULD HAVE KNOWN; it does 2 things: It is objective reasonable officer inquiry It protects officers from having to predict the course of law they aren’t responsible if the Court newly articulates a principle of law they couldn’t have complied with or known about; but if the law is clear, and they should’ve known about it, and they violate it, they are liable ^^^Can be decided on SUMMARY JUDGMENT 3 Aspects of Harlow It is untenable to apply different rules of immunity to 1983 & Bivens actions The Court applied the immunity standard to all governmental officials exercising discretionary functions It limited its holding to actions for damages (not a qualified immunity in cases of injunctive relief) Anderson v. Creighton (U.S. 1987): Bivens case; the level of specificity of the immunity issue; FBI agents conducting warrantless search of home seeking a bank robber; the officers say the warrantless search was permissible because it was justified by exigent circumstances; question about whether there were exigent circumstances; legality of search not determined on SJ but not entitled to immunity because 4th Amendment is clearly established (the officers don’t get qualified immunity because the right not to be searched except for on PC or exigent circumstances was clear); the Supreme Court reversed; it must be determined whether the search was done with PC or exigent circumstances which requires an examination of the information the officials had the objective question of whether a reasonable officer could’ve believed that the warrantless search was unlawful, in light of clearly established law and the information the searching officers possessed (subjective beliefs are irrelevant) Raises a KEY ISSUE in a lot of immunity litigation: They just said it’s clearly established The key problem is the level of generality: the 8th Circuit is looking at this at too high a level of generality by just saying there’s a clear rule of 4th Amendment law but the problem is that it kills immunity and it makes a rule of pleading—anyone can plead a constitutional violation with such a level of generality It must be a more particularized, relevant inquiry—looking at whether a reasonable officer would know that what ANDERSON was doing violates constitutional rights The contours of the right must be sufficiently clear that a reasonable official would understand that WHAT HE IS DOING violates that right (not whether there’s a rule of law the officer should know about but that what he did violates the clearly established law); it’s a more specific question Harlow issue: still a threat of discovery chilling decision-making with this new case; we’re looking at the circumstances of what the D did in this case (there’s a factual dispute) and you can’t really resolve all of 69 this on summary judgment; the Court said it may be impossible to resolve these questions without discovery; (1) look at what the P alleges (if the D is going to be immune, even looking at facts most favorable to P, then D is immune); (2) if wouldn’t be immune at that stage, then there’s a disputed issue of fact and limited discovery should be had if necessary; this is going to be determinative of immunity Effect on SJ: should be resolved at earliest stage of litigation; minimal discovery can be had that is tailored to the immunity question In some cases, it won’t be possible to resolve the immunity question before trial but the Court hopes that in most cases, through a focused approach, it can be done before trial RULE: fact-specific inquiry as to whether a reasonable officer would know that what he did would violate a constitutional right; the Court says it’s still objective, but it puts the reasonable officer in the SHOES OF THE DEFENDANT (or assumes the D is a hypothetical reasonable officer who knows the facts, situation, and law, etc.); it does restrict immunity because even if an abstract rule of law is clear, the D might still get immunity because it’s not clear that what he’s doing violates the Constitution Hope v. Pelzer (U.S. 2002) [thorough explanation of the qualified immunity standard]; it combines the question of whether a reasonable officer would know that what he is doing would violate the Constitution + how you figure out if the constitutional right is clearly established [whether there has to be a decision on the issue or whether you can infer; or whether you can look at circuit courts, etc.] Facts: hitching post case; it was an 8th Amendment violation; Issue: whether the officers were liable here or whether they could get qualified immunity Procedure: 11th Circuit and Supreme Court has already decided that the P’s constitutional rights were violated (8th Amendment); the issue here is immunity: the 11th Circuit based the immunity on the fact that there weren’t cases that were materially similar that’s the wrong standard according to the Supreme Court Analysis: the issue is the same as comes up in criminal violations = knowing violations, § 242—a D can willfully violate the Constitution if he had fair WARNING that what he was doing violated the Constitution; it adopted the § 242 standard; the issue is FAIR WARNING THAT IT WAS A CONSTITUTIONAL VIOLATION AND WHETHER D HAD THIS RE: WHAT HE WAS DOING But what does fair warning mean? Block quote from pp. 280–81—there’s not a single standard of fair warning; it depends; sometimes there is going to be a need for very similar precedent (ex. if a Supreme Court case says we hold that x, y, and z violates the Constitution but we don’t reach the question of what would happen if w were also present and you’re case deals with w; then since the Supreme Court explicitly didn’t decide w and unless there are cases that are very clear at least in the circuit of what happens with w, there’s NO fair warning); on the other hand, sometimes general statements of the law CAN give fair warning—a principle of law being so clear and broadly applicable that someone has fair warning even if there are no similar cases (ex. a line of 8 th Amendment cases saying torture violates the 8th Amendment and dealt with a bunch of different types, the fact that D could cook up a new way of torturing someone doesn’t mean they don’t have fair warning because the general principle is clear) Analysis, pp. 281–83 First: it is so obviously cruel and unusual that the 8th Amendment gives fair warning; the Court suggests that this is one of those blatantly unconstitutional things but the Court doesn’t rest on this because there’s enough other stuff that makes it fair Second: two bindings cases in the circuit + the AL Dep’t of Correction Regulations (suggesting there have to be real protections built in to the hitching post) + DOJ report saying it was unconstitutional ***What the Court says about the precedents: they don’t deal with hitching posts—Gates (giving a laundry list of things that guards can’t do—shoot at people’s feet to keep them moving, make them stand on stumps for long periods of time, and handcuffing to fences for long periods) but the specific inclusion of the handcuffing to fixed objects for long periods of time put them on fair warning; Ort—said it was permissible to withhold water from prisoner who refused to work BUT it would be different if the water was withheld as punishment once they got back to jail the Court said this was enough to put them on notice; it’s reading the negative into the case Regulations: there were specific safeguards limiting them 70 Rules Threshold inquiry in immunity cases: whether there’s a constitutional violation here, there was Officers will not be liable if their actions did not violate clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would’ve known (the facts of previous cases need not be materially similar in a rigid fashion) Policy: NOTICE to the officers Officials can still be on notice that their conduct violates established law even in novel factual circumstances the cases need not be fundamentally similar; cases with fundamentally similar facts provide strong support though Looking @ regulations if the officials were constantly violating the requirement, that’s an indication that they were aware that their conduct was wrongful Dissent (Thomas): doesn’t think the law is clearly established; if officers of reasonably competence would disagree about the law, it’s not clearly established; AL was the only state who did this and there was no contrary authority He draws on different quotes from immunity: it recasts the immunity standard, that it protects all but plainly incompetent and knowing violations of the law (presumption of immunity; he also says we shouldn’t look at specific allegations because they haven’t been proved, so we should look at it as just using the post; and then he looks at the sequence of law differently there are some district court cases from AL that deal with hitching posts that thought they were ok; the guards are more reasonable to rely on the district court cases that are more specific than trying to read the tea leaves of circuit and Supreme Court precedent; these people live in a country place and might not have known about the DOJ He recasts things in a way that’s more sympathetic to the actors Summary It’s a sliding scale Obviously unconstitutional (don’t need specifics) Not obvious (more fact-specific) Hierarchy of authority Supreme Court Circuit Court other factors Questions on Determining Qualified Immunity Order of Battle: Saucier v. Katz (U.S. 2001)—the Court held that courts must FIRST decide the constitutional question; but then Scott v. Harris (U.S. 2007), Breyer argued that the courts should not decide the constitutional question if the person is clearly entitled to qualified immunity; Pearson v. Callahan (U.S. 2009), overruled Saucier’s requirement that a court decide the constitutional issue first; the judge should use their sound discretion in deciding the issue that needs to be addressed first It’s attractive for lower courts to skip to immunity because they won’t have to go to trial BUT the problem is that you never get legal decisions and the law never develops Saucier: must decide constitutional issue first; if there’s a violation, then you can go to the immunity issue Dissent: this is a waste of resources when the person is obviously immune Pearson: need not decide constitutional question if person is clearly entitled to qualified immunity; it’s in the sound discretion of the district court issue: does the district court have a clear enough sense of what law applies even without a trial Immunized Ds Who Object to the Legal Ruling: if the D wants the court to decide the constitutional issue so that it knows how to act; Camreta v. Greene (U.S. 2011)—the court held that it COULD REVIEW the constitutional issue at the request of the D Immunized D sort of gets screwed—do you have to live with a question of law you hate but not be able to appeal? NO, the Court can grant cert even to the immunized party Looking at the generality of the inquiry: Groh v. Ramirez (U.S. 2004): federal agent got a warrant signed by the magistrate BUT IT WAS FACIALLY INVALID; he filed application to the magistrate with specifically what he was searching for; magistrate issues the warrant but it doesn’t incorporate the list of things the person is searching for; the Court held that the agent wasn’t entitled to immunity because it was so obviously in violation of the 4 th Amendment; this violated the text of the 4th Amendment—“warrant must state with particularity what is being searched for”; nothing in the warrant so it was obviously unconstitutional Court looked at the HIGHEST LEVEL OF GENERALITY POSSIBLE: the text of the Constitution itself 71 Dissent: The focus should be different—reasonable officer might be mistaken on the fact, that the warrant was proper (that it was incorporated or listed); a reasonable officer will assume that the packet might have all the information; looking at it more from how reasonable officers actually act, not actually studying the language of the warrant because they assume the magistrate will get it right Limiting Groh: Messerschmidt v. Millender (U.S. 2012)—the Court limited Groh in the situation where the warrant was NOT facially invalid; it wasn’t unreasonable to rely on the magistrate; the officer did a bunch of investigation and writes it out for the warrant, he shows it to a superior who says it’s ok (internal vetting) and then takes it to the magistrate; conducted search and finds nothing; assuming the warrant was overbroad, do the officers get immunity? 9th Circuit said no, the officers should’ve known BUT the Supreme Court said he did everything he could’ve reasonably been expected to do Exception: the fact that magistrate signs off doesn’t automatically get him off BUT he asked for a lot of advice and the Court found that he acted reasonably and shouldn’t have been expected to know he was violating clearly established law Factual inquiry not simply at the law but also really at what the officer has reason to know given the circumstances here (a more fact-based analysis) Ashcroft v. Al-Kidd: saying don’t inquire into basic principles; the history and purpose of the 4th Amendment can’t establish clearly established law Over-Reliance on General Constitutional Principles: Pelzer focused on the degree of similarity of precedent and Creighton focused on the level of generality with which the court will consider the question; York v. City of Las Cruces (10th Cir. 2008)—police arrested dude after yelling “bitch”; the court held that the officers weren’t entitled to immunity because there was a fighting words doctrine putting the officers on notice that the language was protected Wilson v. Layne (U.S. 1994): the law is not clearly established with lack of controlling authority in the jurisdiction at the time of the incident or a consensus of persuasive authority; split of circuit authority strongly indicates law is not clearly established What body of law clearly establishes? Doesn’t have to be in the binding jurisdiction necessarily You look FIRST TO SUPREME COURT, THEN TO CIRCUIT AUTHORITY (this is a strong indication that law is clearly established); if no circuit authority and/or circuit split, it may not be clear Need a clear consensus or obvious trend in the case law; the court’s going to do this when it gets a chance; a big split shows it’s not the case BUT if 1 circuit is an outlier, the law still might be clearly established 6th circuit doesn’t look outside much Safford v. Redding (U.S. 2009): the fact that a single judge disagrees with the law doesn’t mean it’s not clearly established Cleveland v. Brutsche (7th Cir. 1989): controlling precedent is NOT the only way to determine whether a law is clearly established; the proper test is whether at the time of the acts there’s a clear trend in case law that it will be in the controlling precedent over time Other doctrines: 3 circuits + no court reaching opposite conclusion; post-incident cases persuasive McMillian v. Johnson (11th Cir. 1996)—absence of past incidents of outrageous abuse doesn’t mean the law is not clear; the Court noted that outrageous conduct is obviously unconstitutional Determining if the Law is Clearly Established: Reichle v. Howards (U.S. 2012): Court had never determined that a person could bring a 1st Amendment retaliation claim to challenge an arrest based on PC & circuit court hadn’t How Long Does It Take? Rule of reason; AND the D’s position also appears relevant to the question (holding higher ranking people to higher standards) If Supreme Court comes out with decision tomorrow and officer violates it the next day, has he violated clearly established law? The courts use a rule of reason—that Supreme Court decisions becomes more clearly established more quickly than circuit courts (~ 10 days not 4 days) The D’s position is also relevant—more likely to find that supervisors should be on notice more quickly than lower ranking officers Factual Disputes: whether the Court should resolve on SJ factual disputes Restating the Approach: approach using 2- and 3-prong tests; Pritchett: (1) identify the specific right the P claims was violated; (2) determine if the right was clearly established at the time of the alleged violation; (3) if so, determine if a reasonable officer in the D’s position would’ve known that his actions would violate that right first 2 are purely legal and 3rd is factual Question of Law 72 Advice of Counsel: magistrate judge case (seems to help establish this); if someone gets advice of counsel, does that give them immunity? The Courts are reluctant to say automatically because it would be easy to get around violating the law BUT if someone does consult counsel that’s a good indication that the law is not clear (pointing in the direction of immunity) Professional Standards & Budgetary Constraints: Youngberg with officials in mental institution if acting under their professional standard as NOT being liable individually for damages; it’s a unique PDP standard for professionals—if they can’t comply because of budgetary constraints, they should get immunity—it’s not clear how this relates to Harlow; there are cases out there that look at the budgetary constraints issues re: immunity and that it doesn’t mean you didn’t violate the Constitution but it might factor into giving someone immunity Ministerial Acts: involving no discretion; suggestion that they don’t get any immunity at all Discretionary Function: 11th Circuit said this requires them to actually be performing a duty within the range of discretion the job entails; HS teacher couldn’t claim for prayer in class Does the Same Immunity Analysis Apply to ALL Constitutional Claims? Generally 4th Amendment requires reasonableness + another layer of reasonableness for immunity; if the court has to decide the constitutional issue, isn’t it deciding the immunity issue? NO—immunity is a further dimension: how the relevant legal doctrine will apply to the factual situation the officer confronts The Court discussed this and has put it mostly to rest: the notion that qualified immunity law should apply differently in 4th Amendment cases; the 9th Circuit argued that since the Graham 4th Amendment analysis looked at a “reasonable” amount of force, that qualified immunity shouldn’t apply if someone used unreasonable force because someone can’t be unreasonably reasonable the Court rejected this: Looking at different inquiries of reasonableness: the 4th Amendment is a balance of what is a reasonable amount of force, weighing the amount of force against the government’s interest; in the course of deciding that 4th Amendment question, a court might sketch out legal rules that govern that SORT of instance Ex. If you have a question of whether officers can use tasers when faced with a passive refusal to act, a court could in conducting the 4th Amendment balance set out a rule about use of less than lethal force; an officer who was faced with the question then, when this law was still in flux about whether he can sue a taser might be entitled to qualified immunity because a reasonable officer might not know that what he’s doing is unconstitutional DIFFERENT inquiry: legal inquiry into what rules govern this use of force v. whether a reasonable officer would know those rules (i.e. whether they’ve been established) Saucier v. Katz: famous for its now discarded order-of-battle mandate but it was a 4th Amendment legal issue Constitutional violations for which one can’t have immunity? Some courts say that one can’t reasonably act maliciously and sadistically under the 8th Amendment Brosseau v. Haugen (U.S. 2004): shooting dude in back while fleeing; the law was clearly established but the application of it was still subject to reasonableness Ryburn v. Huff (U.S. 2012): going into woman’s home because suspecting son of going to shoot up school; she sued alleging there was a search with no warrant they had a reasonable basis for concluding that the 4th Amendment allowed them to enter her home if there were an objectively reasonable basis for fearing that violence was imminent Violation of Laws Other Than Those Imposing Liability: whether a person who violates another law can forfeit qualified immunity Davis v. Scherer (U.S. 1984): employee of highway patrol was fired without a hearing for having a second job; claimed that Ds forfeited their immunity because they violated agency regulations; he argues his termination is without PDP (this happens when the PDP law is in flux); the Court agrees the employer with be qualifiedly immune for the DP violation; but there was a clear rule of the FL Highway Dep’t; the employee argued they should forfeit immunity because they violated a clearly established law (the regulation); the Supreme Court said NO; whether officers forfeit immunity by violating a clear rule that controls their conduct but which that rule is not a violation that gives rise to the constitutional claim; the Court held they didn’t forfeit their immunity The question is whether the law that is the BASIS of the cause of action clearly established (the DUE PROCESS LAW); if no, then the immunity still applies; not looking at the agency regulation even if it’s clearly established; the focus is on the law that gives rise to the claim Officials sued for constitutional violations do not lose their qualified immunity merely because their conduct violates some statutory or administrative provision 73 Harlow: can lose immunity for violating clear statutory rights when the violation is BASED on that statute These officials become liable for damages only to the extent that there is a clear violation of the statutory rights that give rise to the cause of action for damages the reg. here didn’t create the right @ the basis of the cause of action; the DP law at this time wasn’t clearly established ***Is what the court did in Hope v. Pelzer consistent with this? Relying on the regulations in determining that the officers weren’t immune; same with Groh: an official is deprived of qualified immunity whenever he violates an internal deadline; relying on departmental rules to check the warrants The regulations here put them on notice—regulations aren’t irrelevant; the fact that there are regulations can put people on notice about the constitutional right at stake; it was evidence that the law was clearly established; the regulations are informative as to why someone should know about the constitutional law; they weren’t stripped of immunity for violating the regulations Spruytte v. Walters (6th Cir. 1985): suing prison officials for refusing to let him have a book sent from someone other than the publisher; there was a PRISON POLICY of allowing them to have these books Summary Reasonable officer standard; how the law applies to what the PERSON is doing at that time; and what body of law can clearly establish law Derivative Immunities Generally This is choice of immunity broadly; who gets what immunity for situations that don’t fit clearly into an established category; may involve private individuals and what immunity they’ll get; how & when to apply the functional analysis and when it’s an inquiry into the availability of immunity at all Dennis v. Sparks (U.S. 1980): conspiracy between private persons & judge regarding an injunction of producing minerals from oil leases (this is the key modern-age under color case that we talked about after Adickes); the judge was entitled to absolute immunity; the issue was whether the private Ds (acting under color w/ conspiracy) were ALSO entitled to immunity; the Court held NO the fact that the judge was immune DID NOT AFFECT the under color issue of the private defendants QUESTION: when can a person’s immunity “rub off” on someone else—that’s derived from the immunity that another person gets? Argument: since they’re acting under color because conspiring with the judge, they should also get the judge’s immunity; if you sue them the judge will have to TESTIFY anyway and this defeats the justification for making him/her immune Absolute immunity doesn’t mean you can never be held accountable; absolute immunity doesn’t mean that judges can’t be witnesses Analysis: looking at common law Burden is on the party claiming the immunity to prove such immunity Gravel v. United States: Senator’s aide was entitled to immunity if either were a LEGISLATIVE ACT or a JUDICIAL ACT BUT judges don’t have to conspire with private parties in order that judicial duties be properly accomplished Argued that the judge would have to be a witness to his own acts but there is no constitutionally based privilege immunizing judges from being required to testify about their judicial conduct in thirdparty litigation Questions & Problems Antoine v. Byers & Anderson, Inc.: court reporter who was behind in reporting and lost some tapes; person couldn’t appeal because he didn’t have a transcript; the person files a suit under Bivens against her, and she argues absolute immunity because she’s a court reporter; whether she gets absolute immunity: Argument: this is a court reporter—the judge doesn’t do this; she’s not performing some sort of discretionary act that the judge would otherwise perform; it’s not like a law clerk who’s exercising judgment on behalf of or in conjunction with the judge These acts don’t involve discretion at all and don’t deserve any immunity Harlow: talks about executive officers exercising discretionary functions suggesting that the functions that get immunity involve a measure of discretion; a task that involves NO DISCRETION (purely ministerial) arguably gets no immunity AT ALL; the court in Antoine suggested this might be the case 74 Oliva v. Heller: district court law clerk dismissed petition for habeas, in which her future employer is one of the litigants, and knew that he was going to work for the state attorney general’s office but continued to work on this anyway as a result of oversight; the D sues her under Bivens, arguing that she violated his constitutional rights by issuing the ruling when she’s self-interested; assume there’s a constitutional violation—she claims absolute immunity because she’s working for a federal judge, thus entitled to absolute immunity Argument: she’s acting as an arm of the judge doing things a judge would do in support of this: in Dennis, the Court said Gravel would give immunity if the act was done by an aide, who gets derivative immunity, because the act would be immune if done by the judge herself; in the conspiracy context, the Court said that no one is claiming the judge needs to engage in conspiracies in order to carry out his/her judicial duties—BUT aides CAN get this derivative immunity The law clerk IS PRECISELY the sort of aide because she’s doing things that would be immune if the judge himself did them Mays v. Sudderth: judge issued writ to Mays when she didn’t respond to subpoenas; the sheriff executed the writ; what immunity does the sheriff get? Can’t sue the judge for what’s IN THE WRIT but can you get around this by suing a person who serves it? Courts say no because that person is just carrying out the judge’s job Richman v. Sheahan: witness to testify and delayed proceedings; the judge ordered the officers to restrain him, they did & sat on him and he died; are they entitled to absolute immunity? Argument: idea that law clerk or aide performing discretionary acts on behalf of judge should get immunity derived from that official because they are basically acting as an aide; there are a number of cases, such as Mays in which a judge issues a writ, a court official serves the writ, and the court will still allow immunity HERE: the officers will argue absolute immunity because they’re just doing what the judge told them to do; BUT this doesn’t work because they arguably go beyond the orders of the judge; they aren’t just following the orders of the judge this is a case that’s not saying there’s something unconstitutional about stopping a disturbance in court; the issue is the MANNER of stopping the disturbance and that something they did ON THEIR OWN; they don’t get absolute judicial immunity when they interpret restrain to mean smother If the judge were just watching this you could argue ratification Waco, ruff him up case, if you sue the guards, it’ll depend on whether the judge did really order them to ruff him up, and arguably they would get the immunity that the judge gets it would be different in Antoine if the judge told her to delay the transcript They could maybe still get qualified immunity for an executive function but they don’t get absolute immunity Stump v. Sparkman: is this still correct that the private Ds aren’t amenable to suit because the judge was absolutely immune? NO—Dennis overruled this! Summary: people acting together and what immunities apply to the person being sued; whether it rubs off on them; also looking at when a person is acting as an aide to an official or following direct orders so that the higher official’s immunity rubs off on the functionary Determining Which Immunity Applies Choice of immunity in which the claim of DERIVATIVE IMMUNITY is absent—when using a purely functional analysis and when using a more of the traditional historical approach Tower v. Glover (U.S. 1984): PD sued by former client, alleging that PD conspired with trial and appellate judges to get him convicted; derivative immunity argument wouldn’t work here after Dennis; the PD argues that he should get immunity in his own right because he as a PD deserves absolute immunity because he’s a participant in the judicial system similar to prosecutors and judges Under color: YES because of conspiracy with judges (Dennis v. Sparks) We talked about this in Polk County—as a general rule public defenders do not act under color of law, thus they don’t get immunity The Court says the standard approach to immunities: (1) look to the common law to determine whether there is a historical immunity for that function historically, PDs didn’t even exist, so this didn’t apply (2) look to the history and purposes of § 1983 can’t create an immunity just because it would be good policy; no immunity for intentional misconduct and nothing else counseling PDs from having similar immunity to judges & prosecutors ***No where mentions function 75 ***This is up to CONGRESS to extend! Cleavinger v. Saxner (U.S. 1985): prison officials & committee adjudicating a prison dispute and found the inmates guilty; the inmates claimed PDP violation; the Court held that the prison officials and other defendants were NOT entitled to ABSOLUTE immunity because under a functional analysis, not acting like an INDEPENDENT judge (ALJ or Art. III) and looked at the factors justifying immunity and didn’t find any present here Rules Parole board gets ABSOLUTE immunity because they are neutral/impartial The prison officials & other defendants get QUALIFIED immunity they need to just follow clear constitutional precedent Analysis The Court uses a FUNCTIONAL ANALYSIS: whether this function is inherently a judicial function; it’s not because the characteristics of judicial immunity aren’t present here (pp. 303-304)—no independence here; no true adversarial presentation; these aren’t professional decision-makers (like art. III judges or ALJs) but are executive officers who report directly to the warden who are just conducting a hearing on the warden’s behalf; they are more like the school board members in Wood who got qualified immunity for deciding what to do with the spiking of the punch ***No where mentions history Dissent: there are a lot of pressures facing prison officials, so they should get absolute immunity Summary History & Policies (Tower) Functional (Cleavinger) DIFFERENCE: the Ds in Cleavinger are clearly executive officers, so they come into the case with a baseline of qualified immunity under Harlow (qualified immunity); they are going from their qualified immunity and seeking to get absolute immunity, to “up” the immunity by claiming they’re acting like judges here (this is a valid form of analysis and argument); the Court said they were acting in an executive function still; the Ds in Tower were coming from a base line of NO immunity, as a private person, as someone who is not immune; it’s a private person only acting under color by virtue of the conspiracy; he’s not an executive officer; the question is whether he gets any immunity—to decide this, the Court goes through 2-prong analysis Function determines immunity for state officials, someone with a base line of some sort of immunity and the question is which immunity applies 2-prong analysis determines immunity for private persons who have no base line for immunity and the question is whether any immunity applies (just like it did for prosecutorial and judicial immunity @ the beginning) In Richardson, Court says we use functional approach when looking at the function the OFFICIAL is acting in but use 2-prong approach in determining whether immunities apply in the first place Notes & Problems Tower and Cleavinger: consistent? Yes, see above Choice of immunities? For functional approach Malley v. Briggs: police conducting wiretap; the officer logged a conversation; a state trooper interpreted it and drew up felony complaints and then issued warrants for arrest with affidavits; a judge signed the warrants; is the STATE TROOPER entitled to immunity? For what? He argues he should be absolutely immune because acting like a prosecutor The Court says that he’s acting like a COMPLAINING WITNESS NOT A PROSECUTOR; this idea comes up in social worker cases (see below) Witness or Complaining Witness: Rehberg v. Paulk (U.S. 2012): why there are different standards for different witnesses; whether a police officer who testifies before a grand jury seeking an indictment gets qualified immunity for being a police officer/complaining witness or whether he gets absolute immunity for being a witness; the Court said that people who are witnesses, who actually testify (at trial or before the grand jury), get absolute immunity; FUNCTIONAL APPROACH: the officer doesn’t lose the absolute immunity for what he says before the grand jury under oath simply because his job is a COP Grand jury witnesses have absolute immunity fear of litigation justifies and chilling of telling the truth; this includes officers who testify in front of a grand jury BECAUSE they aren’t acting as a “complaining witness” because it is not application for arrest warrant or initiating a prosecution Complaining witnesses have qualified immunity 76 Social workers: Austin v. Borel (5th Cir. 1987): mom notified police department of sexual abuse of her daughter; police referred to child protection agency; social worker investigated and contacted the DA’s office; the caseworker filed a VERIFIED PETITION with the results of the investigation; is the social worker immune? This social worker doesn’t get absolute immunity because acting more like a COMPLAINING WITNESS There are cases in some jurisdictions where the social worker actually institutes legal action, where the social worker is the one who files the petition in court, and those circuits in these circumstances find they’re acting like prosecutors and give them absolute immunity Immunities & Private Defendants Introduction Whether private Ds receive immunity, if the person is acting under color We saw this in Lugar: one of the issues in deciding that the company that sought the garnishment was actually a state actor is whether that was fair when following a facially valid procedure; the Court in fn. 23 reserved the question stating that it was a question of immunity not affecting the PRIMA FACIE case The Court answers this in Wyatt Cases have very different factual situations Wyatt v. Cole (U.S. 1992) Whether private individuals acting under color of state law in attaching private property are entitled to immunity in a 1983 action (Lugar issue) the Court held NO; similar facts, the statute for the pre-judgment attachment of property was found unconstitutional The Court takes the approach you’d expect from Tower, private party exercising no governmental function but is nonetheless a state actor (Lugar tells us they are) ANALYSIS: (1) common law & history—distinctions between complaining witnesses and those entitled to absolute immunity; for malicious prosecution, if acting without malice, wouldn’t be held liable, good-faith defense, so there’s sort of a historical basis for immunity but it doesn’t translate into the Harlow objective immunity (2) justifications/policies for immunity weren’t present here: holding this person responsible doesn’t harm the public good; it is to encourage individuals to enter into government service and to prevent overdeterrence – this is n/a here: here it’s a private party pursuing his own financial end, no public good involved or government purpose; no need to encourage people to bring replevin actions SCOPE: qualified immunity is not available for private Ds faced with 1983 liability for invoking a state replevin, garnishment, or attachment statute Didn’t answer (specifies that this is a very narrow holding: whether qualified immunity as announced in Harlow applies to…): whether private Ds would be entitled to an affirmative GF/PC defense & what would happen if this were a private person in a different context LOWER COURTS: they did grant a GF immunity and they found that in other contexts, private individuals could claim qualified immunity Wyatt on remand: adopted the GF defense, where the Ds neither knew or should’ve known that the procedures were unconstitutional shouldn’t be held liable absent a showing of malice & evidence that they either knew or should’ve known of the statute’s unconstitutional infirmity Limits of Wyatt: Sherman: doctor administering help to mental patients pursuant to a court order; is he entitled to qualified immunity? The officers are making him do this; how is this different from Wyatt? Here he’s following court orders and it’s serving a government purpose; not acting independently pursuing his private goals when you have someone acting jointly with government as the technical arm of the government performing a job for the government then the private D can get immunity, essentially derivatively Not a private party pursuing private ends A person acting jointly with government pursuing government ends Rodriques: private physician conducting vaginal search for drug COULD assert qualified immunity Sanchez: doctor performing abdominal surgery for cell phone even though X-rays didn’t show it there was NOT entitled to qualified immunity Richardson v. McKnight (U.S. 1997) 77 Private prison guards working for private prison that is a major for-profit corporation; has minimal state oversight and interference—not entitled to qualified immunity in 1983 suit ANALYSIS (Tower): functional approach doesn’t apply here because not dealing with people in government by private individuals (1) historically, no tradition giving immunity to private prison guards (2) policy didn’t support immunity under functional approach mere performance of a governmental function doesn’t make the difference between liability and immunity; it was a for-profit institution; the guard wasn’t acting for government but a profit-making body that had more freedom to reward and punish and who had incentives to act in a certain way to keep the government contract; characteristics of the employer driven by market pressure Unwarranted timidity: not present here because it’s a for-profit company with competitive pressures & deep pockets SCOPE: private firm systematically organized to assume a major lengthy administrative task with limited direct supervision by the government and which does so for profit and potentially in competition with other companies Lower courts to determine state-action issue Limited to private firm, systematically organized to assume a major lengthy administrative task with limited direct supervision by the government and which does so for profit and potentially in competition with other companies (i.e. not private individual briefly associated with a governmental body or acting under close supervision); NOT a private individual briefly associated with a government body, serving as an adjunct to government in an essential governmental activity, or acting under close official supervision Did not answer whether GF defense was available Reach of Richardson: various note cases Two cases with private individual immunity, Wyatt: individual can’t claim immunity who acted jointly with the state in garnishing property because (1) common-law good-faith immunity didn’t translate into Harlow objective immunity and (2) policy wasn’t in favor of it because it was an individual acting for private ends (preventing over-deterrence wasn’t applicable) and no need to encourage individuals to enter government service because the individual wasn’t acting in government service and in Richardson: where court held that guards who worked for a private prison that operated under a long-term state contract largely independent from the state couldn’t claim immunity; the characteristics of the employer counseled against immunity DESPITE these holdings, lower courts still found individuals immune when individuals weren’t engaged in individual decision-making for their own benefit but working closely with the state in an individualized joint decision they aren’t pursuing private ends Filarsky v. Delia (U.S. 2012): Court finds immunity for private defendant suggesting lower courts were right all along P = firefighter who was absent from work and eventually terminated; city had labor lawyer to conduct interview & threaten suit; the Ds ALL got immunity; lawyer is working with the state to fulfill a state end; the Court used the standard approach—(1) common law: didn’t differentiate between part-time and full-time servants and (2) policy: it’s important that the state be able to attract good people to work for it even on individual projects and important to prevent over-deterrence when someone is working on behalf of the state to achieve a state goal Held private D was entitled to qualified immunity (labor lawyer) ***Is consistent with the previous cases because it’s someone who is really working with and for the government and not for private ends or for a for-profit corporation ANALYSIS: Common law—supported immunity; private citizens engaged in government work and conducting criminal prosecutions; didn’t distinguish between full- and part-time employees, either Policy—supported extending immunity because lawyer was working for the state; this was concerned with the public good 6th Circuit applying Filarsky: found psychiatrist who worked for private non-profit entity providing health care for a prison was NOT entitled to qualified immunity for deliberate indifference History: no immunity for private doctors working for the government Policy: differences between public & private employers from Richardson applies here 78 6th Circuit in Gregg v. Ham: bail bondsmen not entitled to immunity because pursuing own financial interests & not working for the government; not historically entitled to immunity Municipalities: Municipalities as “Persons” and the Reach of Municipal Liability The Foundation Generally We’ve been talking about suits against individuals (an individual in that person’s INDIVIDUAL or PERSONAL capacity); the KEY is that the individual defendant is the real party in interest & their bank account is on the line and a judgment would run against the individual as such Why a § 1983 plaintiff wouldn’t be content with suing just individuals: No deep pockets (with municipality, you have that) Jury is more sympathetic to the individual (as opposed to an entity) Individual immunity (whereas municipalities aren’t) Hard to identify the individual who’s responsible (easy to identify the municipality) Nature of constitutional violations (i.e. detainee in a city jail and being held because he can’t make bail; he’s upset about being in jail; he’s in a cell, night shift, only one jailer, doing his best to check on everyone; detainee commits suicide; his estate sues for SDP violation; PROBLEM: is the officer deliberately indifferent? Probably not; lack of funding case & it’s easier to argue the government is responsible for failing to adequately staff the jail—systemic problem can lead to harm) In Monroe v. Pape, municipalities were not “persons” subject to suit under § 1983 this was a PROBLEM after this case that P tried to get around By brining Bivens actions against municipalities—this didn’t work Pendant party jurisdiction BUT in 1978 Monell reversed Monroe in the proposition that municipalities are not persons, concluding that Congress intended for municipalities & other local government units to be included under § 1983 BUT municipalities can only be liable for injuries caused by their policies or customs Municipalities now ARE PERSONS, meaning they are potential Ds in § 1983 actions BUT, Monell set out narrow situations in which municipalities were proper defendants—so the law is essentially an endeavor to figure out what situations give one the ability to sue a municipality Monell v. NYC Dep’t of Social Servs. (U.S. 1978) Class of female employees who work for NYC Dep’t of Social Services; one gets pregnant and pursuant to the policy has to leave work early without pay; to NY Board of Education & Chancellor and Dep’t of Social Services & Commissioner & NY mayor in their official capacities for official policies compelling pregnant women to take unpaid leaves of absence before such leaves were required for medical reasons; they sued under § 1983, seeking injunctive relief & backpay ***Obviously today and back then this was a EP violation Suit is against city & officials IN THEIR OFFICIAL CAPACITY (just a way to get to the city) The question: can Monell sue the city? The Court uses the case to overrule Monroe part that said municipalities weren’t persons I. The non-person rule was based on a misreading of history and the legislative history of § 1983; the legislative history showed that Congress didn’t think it could force a municipality to keep the peace but nothing suggested the municipality couldn’t be responsible for its own wrongdoing; they can be responsible when they themselves are at fault; Court looked at the “dictionary act”—person involved BODIES, corporate and politic and takes this as additional support so NEW YORK CITY IS A PERSON AND CAN BE SUED II. DISCUSSION WHO What is a “municipality”? Fn. 54: they are local governing bodies & there’s no constitutional impediment to suing these bodies; fn. 54: there’s no 11th Amendment problem here because “our holding today is … limited to local government units which are not considered part of the state for 11th Amendment purposes” states and its arms (states, state agencies, universities, etc.) have 11th Amendment protection but local government units that are not arms of the state do NOT have 11th Amendment protection and are municipalities subject to suit; the definition interrelates with 11th Amendment question of what is a state 79 Official capacity suits are just another way of suing the entity (Fn. 55): individuals sued in their official capacities are municipalities and subject to suit; ex. suing A.C. Wharton in official capacity is a suit against the City of Memphis (just another way of suing the entity; suing the person NOT as an individual but as a representative of an means of reaching the entity) WHEN Local governing bodies can be sued under 1983 … where the action that is alleged to be unconstitutional implements or executes a policy statement, ordinance, regulation, or decision officially adopted and promulgated by that body’s officers (1) official policy, (2) promulgated by body’s officers; ***here, decision to send her on leave was implementing official policy and the persons in the department are the ones who promulgated that policy (they are the ones responsible for it) ^ within this, custom with the force of law is included—if the deprivation were pursuant to government custom, then it would satisfy the official policy portion (equating custom w/ force of law with policy) (Adickes is imported) ^ within this, on the other hand, not liable unless action pursuant to official policy of some nature caused a constitutional tort this is a much broader conception of liability; doesn’t require that someone is implementing an official policy but just has to be PURSUANT to an official policy of some nature; broad terms, causing a TORT; suggesting when there’s a policy in the background that causes a constitutional tort could give rise to § 1983 liability more in tort-like proximate cause terms as opposed to requiring that the decision actually implement an official policy ^ upshot: municipalities cannot be liable under respondeat superior; the language of § 1983, talking about liability against person who subjects or causes to be subjected, forms the idea of causation underlying municipal liability—the municipality has to actually cause the violation (equation: the employee’s tort is the municipality’s liability if the m caused the e to cause the harm) RULES Congress intended municipalities & other local government units to be included among those persons to whom § 1983 applies (overruling Monroe) They can be sued for monetary, declaratory, or injunctive relief where the action implements or executes a policy statement, ordinance, regulation, or decision finally adopted and promulgated by that body’s officers Local governments can also be sued for constitutional violations visited pursuant to the governmental custom (Adickes) But the municipality cannot be liable under respondeat superior or when the policy doesn’t cause a constitutional tort the official policy must “cause” the employee to violate another’s constitutional rights BUT it can’t just be based on the employer-employee relationship; a local government may not be sued under § 1983 for an injury inflicted solely by its employees or agents; instead, it is when execution of a government’s policy or custom, whether made by its lawmakers or by those whose edicts or acts may fairly be said to represent official policy, inflicts the injury that the government as an entity is responsible for under § 1983 ***going beyond the idea of the body’s officers and that official policy can come from lawmakers or OTHERS if their edicts or acts represent official policy there are policy-makers who are not actually the body’s officers; this broadens the first pass—still focused on acts pursuant to an official policy but suggesting that those who make the official policy aren’t just body’s officers but others whose edits or acts make official policy Two theories (1) Unconstitutional policy put into effect and constitutional violation implements or executes that policy (2) If some policy causes a constitutional tort Either way, no respondeat superior; it must be something the municipality is responsible for that CAUSES the harm; there are policies favoring RS but the Court doesn’t believe that’s what Congress intended OFFICIAL POLICY & CAUSATION: the Court said this case is definitely pursuant to official policy; it seems to be explaining the idea of the causal link by saying that the requisite causal link is the policy being the moving force behind the violation problem with this is there’s not tort concept of “moving force”; it’s a bizarre concept of what the causal link is & never really defines it Court said municipals don’t get absolute immunity but reserves the question of whether municipalities may have SOME immunity 80 Development since this—strands of analysis/operate theories of municipal liability harkening back to Monell Pembauer & Praprotnik: Canton: Immunities in Suits Against Municipalities Introduction: Owen held that traditional immunities do not apply in suits against municipalities and Brandon applied this rule to official capacity suits against individuals Owen v. City of Independence (U.S. 1980) City manager appointed Owen as chief of police for an indefinite term; there was a dispute over the police property room, where guns & drugs got out; the City Council investigated it; the Councilman announced it was the fault of Owen; the City Manager discharged him the next day; Owen wasn’t given notice for his discharge or a hearing; he sued the city, the city manager, and the city council alleging a violation of DP for his discharge and a SDP violation (stigma) ***Here, there’s a city body firing the police chief & he sues arguing that this firing without statement of reasons & hearing & opportunity to clear his name violates PDP this is clear after Roth (but it hadn’t been decided after this); sues city officials in their official capacity The THRUST of the claim is against the city The lower court held that The Ds were proper here and the suit was proper There was an official policy/custom responsible for this; the policy was: the city council making the decision to fire the police chief (they’re the body’s officers)—the decision is promulgated by the body’s officers & the termination is implementing the decision by the body’s officers the difference between this and Monell is a ONE-SHOT DEAL but is still implementing a decision from the body’s officers This is enough to constitute policy under Monell: “official conduct of the city’s lawmakers … such conduct amounted to official policy causing the constitutional violation” it doesn’t have to be a pre-existing written policy The respondents had immunity because the law wasn’t clear @ the time of the act (individuals) and municipality having immunity based on its officers (“We extend the limited immunity … to the individual Ds to cover the city as well because its officials acted in GF”) The Court says NO QUALIFIED IMMUNITY FOR MUNICIPALITIES (making them very attractive defendants) History doesn’t support immunity for municipalities (some think this analysis is dead wrong) Policy (see B.) B. RULES [policy supports holding municipality liable] Tower reasoning of not extending immunities to municipalities: legislative purpose and public policy Plaintiffs would be left remediless (because the individual Ds are immune); damages remedy is a vital component for vindicating constitutional violations (the Court doesn’t want hurt people to go without redress); AND It would be a deterrent on the municipality (this will motivate policy-makers to take action to prevent constitutional harm by having unconstitutional policies that subject them to liability); COURT is recognizing the danger of claims falling through the cracks and liability will prevent those who make the systems to make sure those systems don’t lead to harm There aren’t overriding public policy considerations here for granting immunity—it’s FAIR allocating to taxpayers who receive the benefit of municipal governance than to force the victim to bear the cost (1) injustice of subjecting the D to liability Damages award coming from taxpayers (2) whether threat of liability would deter willingness to execute the office with the decisiveness and judgment required by the public good Wouldn’t be a deterrent because it isn’t personal liability Proper allocation of costs with municipal liability between the 3 players involved Victim: compensated for injury Officer: so long as acting in good faith will be shielded from personal liability (pre-Harlow, so now if he’s not qualifiedly immune) Public: forced to bear the costs all together in certain situations Brandon v. Holt (U.S. 1985) [ties everything together with the PLEADING ISSUE] 81 MPD charged with assault; he was known to be extremely violent; he beat some teenagers up after finding them making out; P sought damages from director of the police department (because they employed him knowing that he was violent); lower court thought he was entitled to GF immunity, stating that Owen didn’t apply because it was a suit against an individual; the Supreme Court reversed, though the P didn’t allege they were suing the head of the police department in his official capacity, they WERE (thus it is treated as against the municipality) They filed suit pre-Monell so sued police chief in his official capacity; question is whether police chief can claim immunity (because he wasn’t being sued as an individual) The Court concludes that the official-capacity suit is a suit against the entity (the city of Memphis); if there’s an official-capacity suit, it means that entity-liability rules applies (thus, here, municipal liability applies and there’s no immunity BUT in order for the plaintiff to win here, the plaintiff has to show Monell with policy/custom) If you’re trying to figure out how to get the municipality, the officer isn’t implementing or executing a policy promulgated by the body’s officers—no one said beat up teenagers if they make out & there’s no custom of violence of this nature The theory would be the SECOND theory that a policy of some nature, failure to train/discipline, has caused the constitutional tort; it is the proximate cause of if the higher-ups had trained or disciplined the cop then he wouldn’t have done this so a policy of non-training is what the municipality DOES that causes the tort; [you can try the custom (1) prong idea, but the Court isn’t really keen on that]; ***standard way of looking @ this: there’s a policy of inaction (think in tort proximate cause analysis) ^^^the Supreme Court doesn’t decide this point RULES A judgment against a public servant in his official capacity imposes liability on the entity that he represents provided the public entity received notice and an opportunity to respond Distinguishing between suits against government officials in their individual capacities and those in which only the liability of the municipality itself is at issue Notes & Questions Key distinction: official-capacity and individual-capacity (important re: immunities) No need to sue municipal officials in their official capacities today because of Monell; it’s just another way of suing the municipality (don’t sue A.C. Wharton, just sue the City of Memphis) some people do still bring official-capacity suits either because they don’t understand the law or because they think it will help their cause to personalize the defendant Daskalea v. DC: courts may dismiss official-capacity claims as duplicative if the plaintiff sues both the municipality and the official in an official-capacity suit Brandon didn’t decide the claim on the merits Municipal Liability for Policymakers’ Unconstitutional Decisions [first strand of municipal liability from Monell] Generally: in Monell, liability for official policy; (1) implements or executes official policy promulgated by officers or others when acts or edits represent policy (Owen & Fact Concerts; Pembaur and Praprotnik); (2) action pursuant to municipal policy of some nature causes a constitutional tort (Canton) In Owen, there’s an official policy from the body’s officers, but it’s just a one-shot deal, not written to apply in the future; and similar to Owen, City of Newport v. Fact Concerts: the council cancelled the contract for a concert because it was a rock band not a jazz band; the band with a contract sued saying this violated the band’s First Amendment rights; can the city be liable? YES—this is in the Owen mold; it’s a decision made by the body’s officers; ***another reason it’s important: it decides that municipalities are NOT LIABLE FOR PUNITIVE DAMAGES Pembauer looks at the ACTS/EDICTS of persons who are policymakers but NOT officers Pembaur v. City of Cincinnati (U.S. 1986) [whether a SINGLE DECISION by a municipal policymaker can satisfy the requirement that it is taken pursuant to official municipal policy] Physician being investigated for fraudulently accepting payments from state welfare agencies for services not actually rendered; there were subpoenas and capiases to get his employees; the police officers went to his work and they wouldn’t open the door; the deputy sheriffs called the assistant prosecutor for advice on what to do; he contacted the county prosecutor who told them to “go in and get them”; they forced open the door and got some people (the wrong people); Pembauer sued the city, the county, the police chief and sheriff, members of the county commission, assistant prosecutor and police officers for a Fourth & Fourteenth 82 Amendment violation this instance wasn’t pursuant to a written policy and had never happened before The city is responsible for the prosecutor’s order of “go in and get them” (the policymaker gave an unconstitutional order) and the decision to break in implemented that policy of the person whose edits/acts created policy (the prosecutor) They didn’t sue prosecutor in individual capacity because they thought he was absolutely immune but this was investigative action so he wouldn’t have absolute prosecutorial immunity Crucial to get municipal liability here because the case didn’t come down until after the break-in; the individuals would have had immunity (?) ANALYSIS The point of Monell is to determine responsibility and the city should only be liable for acts for which it is responsible; it is responsible for what its policymakers do; not only the body’s officers make policy but there are others whose edits or acts can represent policy; policy can be a one-shot deal or something repeated Who is a policymaker? [Part II is a PLURALITY] Municipal liability attaches where the decision-maker possesses final authority to establish policy (looking @ finality; determining whether the person has final authority is a question of STATE LAW—where does state law, including municipal law, vest final decision-making power?) Holds municipal liability attaches were: A DELIBERATE CHOICE TO FOLLOW A COURSE OF ACTION MADE FROM among various ALTERNATIVES MADE BY the OFFICIALS responsible for establishing final policy with respect to the subject matter in question BUT what about delegation? See fn. 12 hypo: *** RULES It must be pursuant to municipal policy so that it’s not respondeat superior liability; BUT it can be imposed for a single decision by municipal policy-makers under appropriate circumstances (i.e. a final resolution by a legislative body or other officials whose acts or edicts can represent official policy) Municipal liability attaches only where the decision-maker possesses FINAL authority to establish municipal policy with respect to the action ordered he/she must be responsible for that decision, as well, in order to avoid respondeat superior liability ***deputy sheriffs just received instructions from the county prosecutor, so the PROSECUTOR is liable (according to state law for his position, etc.) Stevens: thinks it should just be a suit against the county O’Connor: thinks the case was over-decided Powell (CJ & Rehnquist) DISSENT: this wasn’t a policy; this is respondeat superior liability; inquiry should focus on the NATURE (general applicability) of the decision and the PROCESS by which it was made (formal procedures, deliberation) SUMMARY Municipality is liable for single act attributed to official policy that an official policymaker makes—this is the case regardless of whether the policy applies across-the-board (Monell) or a one-shot deal (Owen & Fact Concerts) Pembauer: issue of policymaking authority—it didn’t rest solely in the legislative body but rather that there were “others” who edits/acts could represent municipal policy; in this case, the Court held that the county prosecutor IS a policymaker with regard to question of HOW to execute a capias the municipality can be liable when the constitutional violation implements or executes the policy promulgated by the decision of a person whose acts/edits represent policy (i.e. a “policymaker”); since the prosecutor is the policymaker, the city can be liable for the unconstitutional action that he ordered—breaking into Pembauer’s office Application of the Owen/Fact Concert liability when it’s the individual policymaker taking the action as opposed to the city council ISSUE: WHO’S A POLICYMAKER? WHO HAS POLICYMAKING AUTHORITY? Some general agreement in Pembauer that what one is looking for is: Look @ state law (whether it vests policymaking authority) Whether the policymaking authority is final authority in the area at issue (according to state law, i.e. Pembauer, whether under Ohio law and Hamilton County law, the prosecutor has final authority to make law enforcement decisions; the majority concludes that the prosecutor does fit this definition) 83 Footnote 12: in the text, “authority to make municipal policy may be granted by LEGISLATIVE enactment or may be DELEGATED by an official who possess such authority” Delegation: the case suggest that in these cases, the delegatee becomes the policymaker—the problem is the fact that someone has authority to make decisions doesn’t mean they’ve been delegated the power; it ultimately hinges on who has the final say Footnote 12 hypo: a sheriff may have discretion to hire/fire employees but is not establishing employment policy (it doesn’t mean the sheriff is the policymaker—whether he is ultimately depends on whether he’s the one who has the final say over employment policy) If there’s no one who can review his decisions, then he’s the policymaker But if the Civil Service Board or some other agency is the one that actually determines employment policy – that doesn’t mean the sheriff is making policy because the decision can be appealed or the commission promulgates a rule that goes against what he’s done (he can violate the rule with his discretion but he’s not making policy) Problem: when determining whether the one with discretion to act is the one with final authority or whether someone else makes policy even if the higher-ups NEVER GET INVOLVED (i.e. sheriff firing someone for an unconstitutional reason; doesn’t mean he’s making policy even if no appeal or appeal rejected; he’s NOT the one who has the final say) City of St. Louis v. Praprotnik (U.S. 1988) [when the person with de facto authority is not the person with legal authority; PLURALITY DECISION]; no one disputes the result in this case but it’s controversial in regard to the dicta P, St. Louis employee, sued for retaliatory actions for a suspension from the Commission; he appeals a decision to the Civil Service Commission—transferred to a lower-level job and then laid off, all in retaliation as he claims; sued, claiming that his lay-off was pursuant to an unconstitutional city policy he claims that the city is liable because the officials who orchestrated the transfer & termination had policymaking authority according to the P; everyone else agrees that the 2 Ds are NOT policymakers because, while they have the discretion to take employment action (the power to do this), they don’t make the FINAL POLICY; the plurality explains that its review of state law leads to the conclusion that the Civil Service Commission & the aldermen have policymaking authority; they then say the 2 Ds are like the hypothetical sheriff in FN. 12 and that they have the power/discretion to act, but they’re not the ones who state law gives policymaking authority ***Concurrence agrees ^ with the FN. 12 analysis—they are just like the sheriff in FN. 12 & aren’t the ones who actually make policy THE FIGHT: the question of delegation—when the municipality can be liable because the policymaker has delegated authority; the plurality takes RIGID APPROACH in determining who makes polic Pp. 348–49: policymaking responsibility can be shared & special difficulties can arise when it’s contended that a municipal policymaker has delegated his authority to another official because if the mere exercise of delegated authority lead to liability, we’d have respondeat superior BUT on the other hand if policymakers could just delegate and be insulated from liability, it wouldn’t fulfill the policy P. 349: plurality suggests different concepts/doctrines that could avoid the problems that come with delegation—one way out of the mess: Custom of delegation, Adickes, theory can avoid a problem of a municipality insulating itself from liability must show a HISTORY and widespread practice of delegation to insulate from liability for unconstitutional acts and no one stepping in to respond, arguing that taking action of unconstitutional nature can amount to municipal custom Ex. every time someone appealed a decision they got transferred to a terrible job, there would be a good argument that there was a custom/usage of punishing people for complaining by transferring them What this is NOT saying: the fact that there is a customary delegation MEANS that the delegatee is the policymaker if the sheriff repeatedly took unconstitutional action, that would be the custom; but this isn’t saying the customary practice of allowing someone else to make decisions becomes a delegation(?) Final policy: if there’s a law on the books that says you can’t do x and the person with authority deviates and gets away with it, it doesn’t make the deviation policy UNLESS it happens all the time so that it’s a custom; if a subordinates decision is subject to review by policymakers (so long as the review is out there whether exercised or not), the person with the power to review still are the policymakers even if they don’t look into or do anything; if they APPROVE A SUBORDINATE’S 84 DECISION AND THE REASON BEHIND IT OR RATIFY IT, their decision would be that of the subordinates Narrow theory: focus on the actual designated policymakers; not looking at the practicalities of the decision-making process ***Unconstitutional custom: pattern of instances of constitutional violations where the policymakers are ignoring it (a specific constitutional violation)—this would be ratification most likely Theory of delegation is very narrow—you can say the policymaker is to blame in a sense—and can in a lot of ways find they aren’t making policy RULES Whether someone is a policy-making official is determined by the JUDGE with reference to state law (custom applies, too) Ratification of a subordinate’s decision can constitute a final decision rendering the person ratifying liable FINALITY The appointing authorities, pursuant to their policy, didn’t make the final decision BUT the Commission did in its review Resembles Pembaur, n. 12: “If city employment policy was set by the mayor and aldermen and by the civil service commission only those bodies’ decisions would provide a basis for city liability. This would be true even if they left the appointing authorities discretion to hire & fire employees and they exercised that discretion in an unconstitutional manner.” Court here didn’t think that the failure to investigate, though discretionary, was pursuant to a custom Brennan concurrence: plurality leaves a GAPING HOLE: it basically is an instruction to higher-ups to just say do your job and don’t bother me; the higher-up still has the authority to intervene but as a practical matter isn’t exercising that authority—he could intervene but he doesn’t really want to; city wouldn’t be liable unless the reviewing officials affirmatively approve both the decision and the basis for it Custom & usage won’t help: it doesn’t deal with cases where the policymaker just says do your job and don’t bother me, so “a city practice of delegating final policymaking authority to a subordinate or midlevel official would not be unconstitutional in and of itself and an isolated unconstitutional act by an official entrusted with such authority would obviously not amount to a municipal custom or usage. Under Pembauer … such an isolated act should give rise to municipal liability. Yet a case such as this would …” Reviewing officials may NEVER invoke their plenary oversight authority –the decision is in effect the final pronouncement but NO LIABILITY UNDER THE PLURALITY’S RULE Example: Assume the Dean decides that he wants to get rid of people for saying they won’t give money to the university; he tells Romantz he’d think it was nice to find a way to get rid of the troublemakers and Dean sits back and doesn’t care what happens—he hasn’t given an unconstitutional order and isn’t intervening and doesn’t know what’s going on problem of Dean suggesting something could happen, could stop it but doesn’t it ***A lot of circuits say rubber stamping is NOT enough to amount to delegation Dissent: problem with the formulation of who has the authority to make a final decision—thinks in this case, the advisors de facto did Questions on Pembauer & Praprotnik Jett v. Dallas: question of who’s a policymaker is a question of law to be resolved by the judge before it goes to the jury, reviewing state law and custom with the force of law; must identify those who speak with final policymaking authority—once they are identified, the jury decides whether that decision caused the deprivation of rights—jury doesn’t decide this person really is the policymaker, but the judge must decide with reference to positive law (***commentators read this as a ratification of the plurality’s approach by not looking @ who as a practical matter is making policy—Jett says NO! This isn’t a jury question but a legal question) Zinermon/Parratt: BOTH inquiries are looking for who is the one who makes policy; question of avoiding Parratt under cases like Zimmerman & Zinermon, and it was the question of who is the State and who makes policy because an act of official policy was not random & unauthorized under Parratt Problem 9 (p. 357): Pastal begins construction on residential project; cracks appear and the chief building official issues a stop-work order; under the code, the city official has the power to impose and lift stopwork orders; months later, the repairs are complete and the chief refuses to lift the stop-work order and Pastal appeals it to the board of appeals; Pastal sues the city and chief building official in state court 85 First issue: is the city a proper D here? City can be liable if the dude is the final decision maker and the dude is acting in his official capacity; there’s no written policy about issuing work orders to stop construction (so not like Monell and no decision by legislative body, so not Owen) but a single decision by an individual—we know that the city will be liable if the individual is a policymaker even if it’s a single decision Is Chief a policymaker: do his acts/edicts represent policy? NO because this decision can be appealed to the board of appeals; not final authority under state law End of municipal liability inquiry BUT before even getting there: could be a DP claim if property interest in the license—BUT this could be an emergency situation and there’s post-deprivation process (Parratt)—in order to have the claim under § 1983, the deprivation has to be attributable to official policy and not be random & unauthorized—chief will say if he did violate the Constitution it was random & unauthorized because he’s not the State (not the one who sets official policy) and no facts that suggest Zimmerman; this is basically Hudson v. Palmer—random & unauthorized deprivation; the ISSUE is does our conclusion that we reached before, that chief is not a policymaker, necessarily mean that his action is random & unauthorized and if he were the policymaker would it necessarily mean the action isn’t random & unauthorized Is a policymaker for 1983 determinative who is the State for Parratt purposes & vice versa a # of lower courts have said that if a person makes official policy and is then the policymaker for the city then by definition that person is the State for Parratt purposes (ex. Note 3, p. 356: court clerk in state judicial district who allegedly repeatedly charged more fees than were authorized under law; P files official-capacity suit, a municipal liability suit, municipal liability NOT individual immunity, for liability, it’s a PDP claim so need to get around Parratt and find municipal liability—the circuit said the claim could go forward—the clerk represented the city on fee issues (final say), the decisions were the official policy of fee collection and weren’t random & unauthorized; because it was official policy, he’s also the policymaker so the claim can go forward against a municipality on the Pembauer/Praprotnik theory) A # of circuits use this equation—if someone’s acts are the acts of the State for Parratt, the person is the policymaker and you can then impose municipal liability BUT you can have someone who’s not a policymaker but still the State under a broader theory of Zinermon not a perfect equation but does match up ***MUST be the final decision within that person’s sphere of authority (i.e. when someone who’s a policymaker goes rogue) Note 5: sheriff raping & murdering a suspect—courts are split, some saying this isn’t his authority but some say it’s during investigation it is law enforcement & the fact that it’s total rogueness it shouldn’t shield city from liability (minority view); mayor molesting children—this isn’t his area of authority McMillian v. Monroe County (U.S. 1997): crucial that municipal policymaker be making MUNICIPAL POLICY & NOT STATE POLICY; everyone agreed that the AL sheriff who took the unconstitutional action was a policymaker but they disagreed on whether he made municipal policy or state policy—whether AL sheriffs represent the state or the county in law enforcement; this matters because if he’s making state policy then it won’t lead to state liability & the 11th Amendment and the state isn’t a person; if he’s a municipal policymaker, then the municipality is a proper D; the Court concluded that the sheriffs are state policymakers based on a review of the AL Constitution, AL law, and other AL policies; the UPSHOT: sheriffs due to the intricacies report to the state on law enforcement; DISSENT: they obviously represent the county and this is unlikely to be a decision that matters because it’s so based on AL history (not a general rule) Issue comes up a lot with SHERIFFS & DISTRICT ATTORNEYS: as a general rule, circuits end up finding they BOTH make county policy, not state policy Van de Kamp: prosecutorial immunity case with suit against the prosecutor’s office for failure to have policies of not disclosing the identity of informants; the court said it was a prosecutorial decision—dude was individually immune—but this didn’t preclude municipal liability if there was an unconstitutional municipal policy: argued that dude made unconstitutional policy of not disclosing the identity of informants the dispute: whether this was POLICY (it was policymaking) for CA or for the County; the 9th Circuit found that he made county/city policy Monell’s Policy or Custom Requirement: Municipal Liability for Facially Constitutional Policies Second inquiry under Monell: the policy isn’t unconstitutional, rather the claim is that a municipal policy that is in itself constitutional caused, in the tort sense, a constitutional violation this is the issue that came up in 86 Brandon v. Holt (argument that Memphis was liable because the city knew/should’ve known that the dude was violating all sorts of constitutional rights and there was a policy of not training/disciplining); rule: court can’t infer unconstitutional policy from one unconstitutional act pursuant to a constitutional policy how can the city be liable? Must be some policy in the background that show the municipality is in essence at fault (can’t infer there’s an unconstitutional policy just because someone commits a constitutional violation) First inquiry: unconstitutional policies generally ANOTHER WAY: distinction for municipal liability for unconstitutional policies and constitutional policies that nonetheless cause constitutional harm Unconstitutional policy: the Court was dealing with liability for facially unconstitutional policies (including custom w/ the force of law), when the actor carried them out, mandated a constitutional violation Lawmakers—across-the-board (Monell—lay-offs were mandated at 5th month of pregnancy) Lawmakers—one-shot deal (Owen—mandating an unconstitutional order, Fact Concerts) Indirect policymaking (Pembauer, Praprotnik) Constitutional policy Established pol.-deliberate indifference (Canton): this is different because it’s dealing with a facially constitutional policy; nothing facially unconstitutional about saying that shift commanders can decide whether to get medical care or nothing facially unconstitutional about not training; nothing is mandating a constitutional violation; the claim: the policy makes it likely that there will be a constitutional violation and that a constitutional violation did indeed occur; city can be liable if the policy CAUSES THE VIOLATION AND IF THE POLICY MANIFESTS DELIBERATE INDIFFERENCE Development of the Policy or Custom Inquiry Monell: city can be liable if policies/customs caused a constitutional violation—issues: what causal link and what sorts of policies/customs Polk Cnty.: policy of withdrawal from frivolous cases didn’t violate the Constitution, so it couldn’t be the basis for liability Lower courts’ approaches An unconstitutional policy that mandated violation of someone’s rights Any municipal policy, even a blameless one, if caused a deprivation of rights Blameworthy policies, those showing deliberate indifference on the part of the defendant, can give rise to liability (now the Supreme Court approach) City of Okla. v. Tuttle (U.S. 1985): the district court gave a jury instruction, allowing a finding of liability for a single incident from inadequate training; a majority of the Court found the jury instructions inadequate because it was liability on a city for a single act by a non-policymaking employee Need independent proof of a policy and a causal link to the violation Rehnquist (plurality): no wrong was ascribed to the municipal decisionmakers; it needs to be more of a conscious choice and they weren’t on notice of the potential constitutional violations Brennan, Marshall & Blackmun: improper because it allowed plaintiff to proceed on RS liability, a policy without showing any actions taken by the city Brennan: city should be able to be held liable for a single incident City of Springfield v. Kibbe (U.S. 1987): car chase, inadequate training of officers; the majority rejected cert but the dissent offered reasoning for their dissent—the city’s conduct must be the “moving force” in bringing about the constitutional violation & where the inadequacy of training amounts to deliberate indifference or reckless disregard Plurality argued that there would need to not be just a showing of municipal policy but some degree of fault underlying it; there’s a need to show a close causal nexus between the municipality conduct and the harm—elevated showing of fault Summary: in order to hold the municipality liable for a constitutional violation that a non-policymaker commits, there needs to be some showing of a policy and a showing of some sort of fault City of Canton v. Harris (U.S. 1989): Court held that in some circumstances the city can be held liable for failure to train its municipal employees; here, a woman was brought to the station and didn’t receive medical attention after evidence that she needed it; there was a municipal regulation that they were supposed to determine whether she needed medical attention & there was no special training involved (this was the alleged cause of her injuries— the city policy gave the shift commander discretion over whether to get medical care but didn’t train regarding symptoms; municipal policy of lack of training caused the SDP violation of not getting medical care for 87 someone who needs it); she sued under 14th Amendment for a SDP violation for failure to receive medical attention while in police custody; the Court vacated & remanded Municipalities can be liable for constitutional harms that a facially constitutional policy causes here, we have a facially constitutional policy (nothing unconstitutional about failing to train someone in recognizing symptoms of emotional distress) but the city could still be liable if the facially unconstitutional policy caused the constitutional violation Direct causal link Rejecting the idea that the policy ITSELF has to be unconstitutional Also, a city would NOT be liable merely because one of its employees happened to apply the policy in an unconstitutional manner (RS liability) The inadequacy of police training may serve as the basis for § 1983 liability only where the failure to train amounts to deliberate indifference to the rights of persons with whom the police come into contact DI standard is NOT the same as the constitutional-violation DI standard How do you show DI? Footnote 10 (see below) Reasons for requiring DI: drawing on Kibbe—it’s necessary in order to show causation; and an idea expressed in Pembauer, that a policy is a conscious choice—the municipality is only going to be liable if it made a conscious choice to train inadequately The policy/custom must be the moving force behind the constitutional violation Need to also show causation; “the deficiency of training must be closely related to the injury” … “that it caused the …”; could this have been avoided if they were trained Municipal liability under § 1983 attaches only were a deliberate choice to follow a course of action is made from among various alternatives by city policymakers ***HERE: in light of the duties assigned to specific officers or employees the need for more or different training is so obvious, and the inadequacy is so likely to result in the violation of constitutional rights, that the policymakers of the city can reasonably be said to have been deliberately indifferent to the need It must be CLOSELY RELATED to the ultimate injury HOW TO SHOW DI: 2 modes of showing DI Clear constitutional duty implicated in a recurrent situation: there are some jobs the city knows its officers will encounter and the city knows that officers are going to be faced with choices of constitutional dimension in doing those jobs; if the city doesn’t train people about the constitutional limits, it’s DI; ex. giving police firearms to arrest felons; the city knows to a moral certainty (footnote 10) that the police will have to made a choice as to whether to use force; if the city doesn’t train police on the constitutional limits of the force, it’s deliberately indifference (making a conscious choice to risk/cause the constitutional violations that could result) Policymakers were aware of and acquiesced in a pattern of constitutional violations involving the exercise of police discretion: if the policymakers then sit by and do nothing, they are deliberately indifferent to the continuance of this constitutional violation; ex. officers repeatedly engage in a certain sort of unconstitutional conduct, the city is on notice they need to do something to stop the problem, and if it doesn’t it’s deliberately indifferent This is objective—requiring actual/constructive knowledge OBJECTIVE INQUIRY INTO WHETHER THE POLICE OFFICIALS SHOULD KNOW OF THE NEED TO TRAIN OR SHOULD KNOW OF THE PATTERN OF VIOLATIONS; not enough to show lack of training but need to show CAUSATION; a close causal link between the policy and the harm FN 11: remand for the question of whether it was obvious that the training was insufficient to administer the written policy; only thing the DISSENT talks about; everyone agrees on the OTHER PART O’Connor (Scalia & Kennedy) dissent in part and concurrence in part: Agrees that where municipal policymakers are confronted with an obvious need to train city personnel to avoid the violation of constitutional rights and they are deliberately indifferent to that need, the lack of necessary training may be appropriately considered a city “policy” subjecting the city itself to liability under Monell; causation must be MORE than simply “but for” and the cause of the injury at issue BUT: there’s NO evidence of deliberate indifference here this was a single incident, so the city wasn’t on actual or constructive notice that the particular omission was substantially certain to result in the violation of the constitutional rights of their citizens 88 ***DEBATE: over whether Harris can meet this standard; majority says remand and dissent as to this objects to this idea there’s no obvious need to train about the ability to recognize symptoms of emotional distress and there’s no showing of a pattern of violations Notes & Questions on Harris Pleading: doesn’t have to be specific factual allegations (Leatherman) but some courts hold that conclusory allegations of municipal policy are not sufficient Municipal Liability after Canton Farmer v. Brennan (U.S. 1994): 8th Amendment case with transsexual put in male gen pop; the Supreme Court held that there wasn’t an 8th Amendment violation because the requisite state of mind wasn’t met (deliberate indifference—in the 8th Amendment and this was a subjective inquiry); the DI standard from Canton is DIFFERENT: it’s objective, not subjective & not the same test as that for the 8th Amendment; the Canton test is just the threshold for holding a city responsible for constitutional torts committed by its inadequately trained agents Farmer in reaching this conclusion distinguished Canton, which is objective deliberate indifference different standards make sense because the 8th Amendment inquiry is looking at what is necessary to have punishment (some idea of malice, which is subjective) but the municipal liability inquiry is more a gloss on the idea of causation in 1983; the Court notes it would be hard to consider the subjective state of mind of an entity Injunctive relief: Monell policy or custom requirement applies to claims for injunctive relief (L.A. Cnty. v. Humphries, U.S. 2010) Monell applies no matter what type of relief Bryan Cnty. v. Brown (U.S. 1997): woman sued county and reserve deputy for hiring a dude who had a criminal history; he pulled her over & used excessive force (4th Amendment); her argument is that the municipality is liable because the sheriff hired the deputy and he’s the sort of person who shouldn’t have been a cop (lengthy arrest record) and the city overlooked this; the Court rejected her claim because she didn’t show that the “policy” was the moving force behind the use of excessive force; furthermore, a showing of a single incident does not establish deliberate indifference it must be the risk of violation of the particular constitutional or statutory right following the decision How does this fit into municipal liability law? The sheriff is a policymaker BUT the hiring itself wasn’t unconstitutional; no allegation that the sheriff told the deputy to violate the Constitution; the theory is that the facially constitutional decision caused the constitutional harm this is different from Canton: no showing that as a general matter, that training was inadequate; there’s not even an allegation of a general failure to screen no established policy this is CHALLENGING A ONE-SHOT DEAL AND CANTON CANNOT BE APPLIED Issue: single constitutional decision by a policymaker, could the municipality be liable if the decision shows deliberate indifference? Can one have Canton-type liability when the challenge is to a single decision by a policymaker that manifests deliberate indifference and caused a constitutional violation; this is a melding of Canton and Pembauer The majority appears to accept that theory—Souter in his dissent says the majority does agree that this is a permissible theory of municipal liability; the majority assumes that this is a permissible theory; the majority implicitly accepts this mushed-together theory; despite that it says that Brown can’t recover here because there’s not a strong enough link between the policymaker’s decision and the constitutional violation On the one hand the majority is saying there’s not really enough for DI because there’s not enough here to put the sheriff on notice that the nephew would use excessive force because none of the crimes really involved excessive force; it’s not as if he had a whole history of armed assaults Lack of causation, there’s not enough to show the decision to hire him caused the harm Underlying this: there needs to be even TIGHTER CONNECTION BETWEEN THE ACTION AND THE HARM IN DEALING WITH THE ONE-SHOT DEAL CASES BECAUSE IN THESE CASES WE DON’T EVEN HAVE A PATTERN TO LOOK AT; absence of a pattern, an established policy, makes it even harder to show But there’s still this second theory (melding of Pembauer and Canton) is potentially important although VERY hard to meet Ex. history of arrests for use of violence by the sheriff 89 Connick v. Thompson (U.S. 2011): the Supreme Court reversed a decision imposing municipal liability for inadequate training of district attorneys in introducing exculpatory evidence (Brady violation) after a dude went to jail for 18 years for a crime he didn’t commit; the Court held that this single incident was NOT enough for DI—they weren’t on actual or constructive notice; proving DI generally requires showing a pattern of constitutional violations by untrained employees Suit against the prosecutor? Prosecutorial immunity; Van de Kamp—can’t get around the immunity by suing the head prosecutor for not properly supervising because it’s still a prosecutorial decision Suit against the city? Problem here is a lack of training on how to comply with Brady; need to show under Canton: lack of training that manifests DI 2 ways— (1) obvious, not here because lawyers know the law! Everyone knows about Brady; there’s CLE & ethical obligations; dissent takes issue with this—there should still be an obligation to ensure attorneys know about Brady (also the case is such a nuanced idea, not a clear rule) (2) pattern, no patter here, this were 4 violations over 10 years – this isn’t a PATTERN The case is just a disagreement over Canton, which deals with a deeper policy debate the majority gets nervous about micro-managing city government; the dissent is a lot less worried about this sort of micromanagement and inherent federalism issues Problems on Municipal Liability Davis v. Mason County: rash of incidents over a 1-year period where individuals were arrested for traffic violations, stopped & severely beaten, and then charges are dropped; the victims sued the county and individual police officers, alleging that the officers violated their 4th A rights and the county was liable because of inadequate training of its officers evidenced by DI to citizens’ constitutional rights (they didn’t send them to a training academy but did field training only—not really followed); under WA state law, the sheriff is the chief executive officer but the WA Civil Service Commission has power to make rules/regulations about administrative stuff—implicit in it is a legislative intent to circumscribe county sheriff’s previously unbridled discretion in personnel matters How to argue this meets Canton? Pattern of violations that were unaddressed = deliberate indifference But they will argue the Civil Service Commission is the policy this would be state policy but you can’t sue the state SOMEONE needs to be deliberately indifferent and we assume that needs to be the policymaker the policymaker who is relevant here is the civil service commission which is a state policymaker, so the county can’t be liable for the state’s deliberate indifference under Monroe County; this comes down to a fight over whether it’s a personnel policy … training is either a personnel policy or a lawenforcement decision to put these untrained people on the streets with guns Issues: what policy are we dealing with? Dispute about state law—the role of the csc and the sheriff, etc. The court split 2-1 finding that this was something within the sheriff’s bailiwick; it was municipal policy and people here can get compensation; the dissent said this was more personnel and would be under the csc which would preclude municipal liability Bigger issue: whether you even need to show an identified policymaker if this is all OBJECTIVE, WHY DO YOU EVEN NEED TO POINT TO AN INDIVIDUAL? Courts are just not clear on this; there are decisions like this that look to policymakers but there’s no definitive law; K would argue you don’t need to identify it because this is objective Horton v. Flenory: D, police sergeant, went to night club and didn’t stop an interrogation that later lead to the victim, P’s, death; D followed a hands-off policy re: private club events; then they later didn’t investigate pursuant to the police policy How do the relatives get compensation? Prima facie case: need to show someone acting under color & constitutional violation Looking @ Flenory and say he’s acting under color of state law; theory for acting under state law? There’s a meeting of the minds, conspiracy, with the policy to not interfere (hard to show a meeting of the minds); delegation the state’s law enforcement job and IS A STATE ACTOR under the public function approach; state violation of 4th Amendment so it’s a good case ASSUME THAT DOESN’T WORK: you can’t show conspiracy and that you won’t succeed under public function Look just at Dlubak: we know he’s a state actor; he was involved here by coming & going and telling the dude he has to stay; DeShaney no obligation to intervene; this is state inaction – someone is seeking to hold the state liable for an injury caused by a non-state actor 90 But is it just state inaction; a failure to rescue? TO GET AROUND THIS: told victim not to leave other similar restraint (preventing dude from leaving and trying to protect himself) or put him in a worse position (arguably when the cop shows up and leaves, this emboldens Flenory to do what he wants) Third Circuit suggested either theory could work To get municipal liability after you get your prima facie case won’t get anywhere with Pembauer—no policy about beating up suspected thieves in clubs You’d go under Canton: identify a policy that is causally linked to the violation & requires showing that policy manifests deliberate indifference (policy = hands-off policy); how to show deliberate indifference to the rights of people like Powdrell Did it cause the harm? The court said this falls under Canton—the city is keeping this policy of not caring about what happens in private clubs; would this work today? Probably wouldn’t be liability here for the city because there’s no causal link; there’s no DI because not a pattern and there’s no obvious link between not getting involved in private clubs and constitutional violations Grandstaff: policeman tried to stop dude, thinking he was a fugitive; they end up on the land of a family, the dad comes out and assists the officers; he goes back home and comes back a 2nd time; the cops shoot him; he sued the city & the police chief (their sole policymaker); nothing happened after this incident Budgetary constraints Private entities: most courts use Monell policy or custom to determine when non-governmental entities acting under color of law are liable under § 1983 for the acts of their employees is this correct? CASTLE ROCK: cops not intervening re: restraining order; custom was alleged that the city doesn’t enforce restraining orders as the basis for liability; the Supreme Court said the restraining order didn’t confer a property or liberty interest so it dealt with the problem; ASSUME you could get past this and the case can go forward on a PDP theory This is a case that states a DP violation because we have a deprivation of liberty or property and it was attributable to AN ESTABLISHED POLICY; not a RANDOM AND UNAUTHORIZED FAILURE TO ENFORCE Logan idea what does this mean for the claim against the municipality? Need to show municipal policy—if this is an established policy for purposes of evading Parratt, it is for municipal liability; then we need to show deliberate indifference; if you have a policy that’s a POLICY for Parratt purposes, it’s a policy that at least should be considered as a policy that’s responsible under the municipal liability theory (could this fall under the first prong of Monell???) Summary Municipal Liability & theories: PM took/ordered unconstitutional act or that the municipality is liable because a policy manifesting DI caused the violation ***Last issue in Municipal Liability—how does this interrelate with individual liability? Are they interdependent? (Heller) Note on Supervisory Liability If you can’t establish municipal liability can you just sue the supervisor as a supervisor and seek to get damages that way? The lower courts historically were receptive to supervisory liability if one could show DI on the supervisor’s part—aware of pattern and did nothing or played a role in the violation Supervisory liability basically mirrored municipal liability because no respondeat superior liability for them The Supreme Court cast doubt on this in Ashcroft Pembauer and Praprotnik addressed when a municipality can be held liable because of decisions of an employee who is in a policymaking position—this is not the same as when a supervisor can be held liable because of the actions of an employee who the supervisor controls Rizzo v. Goode (U.S. 1976): a supervisor cannot be held liable on a respondeat superior theory (same as municipality); Court refused an injunction against supervisors of the police department to improve policies in handling citizen police abuse complaints; the Court relied in fn. 58 in Monell FAILURE TO SUPERIVSE IS NOT ENOUGH TO SUPPORT § 1983 LIABILITY LOWER COURTS: have allowed supervisory liability if the D was personally involved: direct participation, failing to remedy a wrong after learning of it, created the policy/custom allowing the unconstitutional practices to continue, or deliberate indifference after being on notice; 6th Cir: supervisor must have encourage the incident or have participated in it 91 Addressed in Ashcroft v. Iqbal, a Bivens action—Court held that government officials are only liable for their misconduct; supervisory liability is a misnomer This is a BIVENS case not 1983 in DICTA it said there’s no supervisory liability under either Bivens or 1983 because there’s no way to distinguish it from respondeat superior; where does this leave us? The lower courts have basically ignored the dicta; rationale: supervisor isn’t be held liable for underlings but for his own supervisory lapses by either being involved in the violation or standing by and doing nothing One could argue that the DI does base liability on wrongdoing Assume you bring the claim against the supervisor, and you can go forward; what defense can the supervisor raise? IMMUNITY—the supervisor can plead qualified immunity because it’s a claim against the individual not official-capacity claims; the P doesn’t need to show policy/custom because it’s not a Canton claim; the P could also seek punitive damages because it’s an individual claim not an entity claim; but it’ll still be hard to show DI The Heller Problem: Linking Individual and Municipal Liability Start of municipal liability Understaffed detention center hypo: someone has incentive to sue the municipality whose in charge of understaffing the detention center because the guard who’s working there may be doing the best he can still isn’t able to prevent the harm The Court recognized this in Owen: municipal liability is important to prevent systemic harms—a bunch of individuals who may be acting in good faith Heller asks if any of this works? Can a person recover against the municipality in the detention center hypo? Does 1983 really protect against systemic harm? City of LA v. Heller (U.S. 1986): city, individuals of police dep’t, and police officers sued for P being arrested without PC and using excessive force in violation of the 4th Amendment; the officers took him in and there was an altercation—he fell through a glass window; the district court bifurcated the trial on the individual police officer liability and the city liability; the JURY held that the officer DIDN’T use unreasonable force; the district court then dismissed the claim against the city, asserting that if the police officer were exonerated, then there was no basis for liability against the city; the COA reversed & the Supreme Court reversed the COA If a person has suffered no constitutional injury at the hands of the individual police officer, the fact that the departmental regulations might have authorized the use of constitutionally excessive force is quite beside the point Dissent (Stevens & Marshall): this inconsistency can be resolved; the officer’s actions could’ve been reasonable in LIGHT of the policies he was acting under This case is per curiam & there weren’t arguments in this case; the implications are HUGE: the lower courts have no idea what to do with it Basic idea: P alleges excessive force when police officers subdue him & push him through a glass window; he sues the individuals & the municipality; 1 individual wins on SJ; case goes forward against 1 officer & the city; the trial court bifurcates—first trying the claim against the individual; the individual wins BUT WE DON’T KNOW WHY (jury didn’t get instructions on immunity so there’s an indication that the jury found the officer didn’t violate the Constitution) the individual officer didn’t violate the Constitution, the municipality can’t be liable because the claim is the municipality is liable for CAUSING THE CONSTITUTIONAL VIOLATION (if no constitutional violation, nothing to be held liable for) You need some constitutional harm and if the only reason the city is being sued is because the city’s responsible for what the officer did WHERE DOES THIS TAKE US? It’s clear that Heller does not apply if the reason the individual is off the hook is immunity; if the individual is immune, that assumes a constitutional violation (Heller irrelevant in those cases) Lower courts find municipal liability in a case like Barrett Tricky question in a case like the detention center hypo—in which there is an individual in play but the reason the individual isn’t liable is because of state of mind the individual is put in a position where he can’t win; if Heller precluded municipal liability then, the whole idea of preventing system harm goes out the window, so does Heller apply in these cases? That municipal liability is necessarily derivative of individual liability or can it be liable for its own wrong even if no individual violates the Constitution Some lower courts tend to just cite Heller reflexively 92 There are some cases that recognize ways around Heller by differentiating between cases of derivative liability (like Heller) and cases in which the municipality is responsible for its OWN unconstitutional policies: see notes (K thinks the municipality SHOULD be responsible in the detention center hypo because it caused the harm by understaffing; it’s not derivative liability) Questions on Heller Collins v. Harker Heights (U.S. 1992): There must be a constitutional violation before a municipality can be found liable BUT § 1983 doesn’t require a showing of an additional element of abuse of government power this is a case where the P is suing directly on the basis of the unconstitutional nature of the city’s policy itself 3d Cir said there this still must be a constitutional violation even if no one person is responsible Difference between direct liability for policies and derivative liability for officers’ unconstitutional acts Problems Barrett v. Orange County: P, former executive director of Orange County HR Commission, alleged he was fired in retaliation for exercising 1st Amendment rights; sued Commission, county and 2 commissioners (a lot of commissioners, but only sued 2 of them); jury form said county not liable if the commissioners weren’t liable The court said this doesn’t work because there are OTHER PEOPLE INVOLVED; maybe those who weren’t sued committed a constitutional violation (not like Heller where there’s only one officer in play); in cases where there are other officers who might’ve committed the violation, the Court won’t find that the municipality couldn’t be responsible Ruvalcaba v. LA: officer released dog on P and kicked suspect; P sued officer and city—alleging officer used excessive force and challenged the dog bite policy of allowing officers to strike suspects who resists dog attacks, to hire people who are prone to violence, and inadequately train them; court BIFURCATED Evans v. Avery: high-speed chase, killing innocent person; at most negligent but officer was following city police department’s policy on high-speed chase; the policy failed to instruct on the constitutional limits of high-speed chases this wasn’t a constitutional violation (intent to harm)? Prison warden gives guards stun guns but no training; injury could’ve been avoided if proper training in place Dodd v. City of Norwich: Officer response to burglary; tried to handcuff him and did it improperly; dude got a gun and scuffle and the suspect was shot; the mother of the suspect sues alleging that the officer seized him unreasonably in violation of his 4th Amendment rights and violated his DP rights she sued the officer, his employer and the city Gibson v. Chicago: officer who was suspended shot his neighbor; he’s not acting under color (because he has no authority) but is the city liable? 10th Cir. held that Heller applies in supervisory liability cases States as “Persons” and the Eleventh Amendment Just focus on the policy here. It will make a lot more sense. Discussion Liability of states/state employees (1 of 3 possible classes of defendants—individuals in individual capacity; municipalities, including official-capacity suits against municipal actors; and states, including official-capacity suits against state employees) Whether state is proper defendant under § 1983 hinges on the 11th Amendment keep in mind the ACTUAL QUESTION that the Supreme Court is tackling is whether states are “persons” (1983 only authorizes suits against “persons”, so if the D isn’t a person, it can’t be sued) Individuals are logically PERSONS Municipalities are PERSONS (Monell) Issue in Will (whether states are PERSONS) To determine whether states are “persons” the Court finds it important to discuss the 11th Amendment because it’s impossible to understand the issue without understanding the 11th Amendment; the whole issue of state personhood rests on a foundation of 11th Amendment law th 11 Amendment: “The judicial power of the United States shall not be construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, commenced or prosecuted against one of the United States by Citizens of another State, or by Citizens or Subjects of any Foreign State.” It doesn’t mean what it says “Judicially created fiction and paradox” 93 Also applies to citizens of the same state Hans v. Louisiana (U.S. 1890): 11th Amendment doesn’t permit a person to sue his OWN STATE in FEDERAL COURT; the Court said don’t worry about the language of the 11th Amendment; the question is whether the citizen can sue its own state in federal court; the language of the 11 th Amendment doesn’t cover that; despite this, the Supreme Court said that the 11th Amendment does bar suits against one’s own state (i.e. as a TN citizen can’t sue TN in federal court); why? The Court said that the point of the 11th Amendment was basically to constitutionalize sovereign immunity and @ c/l states enjoyed sovereign immunity regardless of who was suing; it makes no sense to think that anyone would’ve ratified the 11th Amendment if it would’ve said you can sue your own state (drafting oversight); the 11th Amendment codifies sovereign immunity— can’t SUE A STATE IN FEDERAL COURT LOGICAL QUESTION: what is a state? See below (1) The 11th Amendment is only applicable in FEDERAL COURT (it’s a restriction on the jurisdiction of federal courts) not state court (2) A citizen of one state can’t sue another state in federal court (i.e. citizen of TN; can’t sue GA in federal court) this isn’t what the 11th Amendment means! What is a state? Municipalities are NOT states (can file a suit, “Kritchevsky v. City of Memphis” in federal court, see Monell & FN. 54 said this applies to local governing units that are not part of the state for 11th Amendment purposes) Why don’t they have 11th Amendment protection? They can set their own policies; they can make their own rules; municipalities can TAX independently of the state/raise their own money; the municipal treasury is separate from the state and can set their own policies to protect their treasury Lincoln County: the Court explained that municipalities don’t share in state immunity because they can make the independent decisions & have independent control over policy & funding Obviously, TN is a state (can’t file a suit, “Kritchevsky v. TN” in federal court) To prevent raids on the state treasury ***Things coming in between Can’t sue state of TN, but you’re a prisoner & think the state is responsible for unconstitutional treatment, can you sue the TN Bureau of Corrections? Can’t sue the TN Bureau of corrections if it’s the an arm of the state; the question for entities that aren’t cities/counties or states is whether they’re “arms of the state” or are they independent entities? Everyone agrees that AGENCIES ARE ARMS OF THE STATE BECAUSE THEY ARE JUST A SUBPART OF THE STATE (TN Dep’t of Corrections can’t sue) Statewide agency or state treasury department? School district? University of Memphis? Assume someone believes that the university have violated the Constitution; can you bring a federal court suit naming as the defendant, “The University of Memphis”? It depends on whether the university is an arm of the state to a large degree their funding comes from state agencies, so a judgment against U of M would target the state treasury; if the state’s not giving it any money doesn’t work or you could just raise tuition but to raise tuition they have to get state permission—ultimately the state calls the shots; unlike a municipality, the U of M can’t make decisions on its own; it’s not politically independent in any way despite the funding issue There are suits addressing state colleges and find that they do have 11th Amendment protection Private entity contracting with the state? Relevant factors—whether the state would be responsible for the judgment; how the state law defines the entity; the degree of control the state has over the entity; and the source of funding ***Does all this mean that there’s nothing you can do? No way to stop the university from violating the Constitution? Assume they have an ongoing practice of violating the Constitution (see Ex Parte Young) Assume U of M had a Monell-like policy—what can you do? Why not sue the state official and say that President Martin is the defendant; the problem is that if you can sue President Martin who will write a check on the U of M bank account, you’re still raiding the state’s treasury but on the other hand, if there’s nothing you can do then there’s no way from using federal courts to stop state entities from violating the Constitution SO, you can sue state officials IN THEIR OFFICIAL CAPACITY for PROSPECTIVE RELIEF TO ENJOIN UNCONSTITUTIONAL ACTS but you cannot sue for retroactive relief 94 Ex Parte Young (U.S. 1980): MN’s attorney general sued in his official capacity for a “confiscatory violation” of the Constitution, arguing that various railroad rates are unconstitutional; they get an injunction prohibiting him from enforcing the statutes; he tried to claim sovereign immunity (under the 11th Amendment) because he was acting & sued in his official capacity, so it was a suit against the STATE; he points to cases that said that a person can’t get around the 11th Amendment by suing a state official in his official capacity in telling that person to cough up money in the state treasury—so there are suits that recognized you couldn’t use the pleading mechanism to raid the state treasury but on the other hand there were cases that allowed injunctions against state officials The Supreme Court rejected this contention This is a suit against an individual; what Young is claiming is that since he’s doing his job, he is covered with the cloak of immunity (that the state is protecting him); the Supreme Court explains that this doesn’t work in cases in which the claim is that the individual official is violating FEDERAL LAW OR THE FEDERAL CONSTITUTION because the Constitution is the Supreme law of the land and supersedes state authority & the state doesn’t have the power to immunize Young vis-à-vis the higher power of federal law; when the claim is a violation of federal law, the state’s attempt to protect him doesn’t work “illegal act upon the part of the state official … use of the name of the State to enforce legislative enactment which is void because its unconstitutional” the federal law strips him of his cloak & subjects his person to the judgment; the state has NO POWER TO IMMUNIZE SOMEONE AGAINST FEDERAL POWER & the person can be sued when the claim is that the state actor is acting unconstitutionally because the state can’t protect him there Everyone calls this the “Young fiction” because none of this would work unless Young were acting under color of state law (he’s still a state actor but he loses his state protection) If the act which the state AG seeks to enforce be a violation of the federal Constitution, the officer in proceeding under such enactment comes into conflict with the superior authority of that Constitution, and he is in that case STRIPPED OF HIS OFFICIAL OR REPRESENTATIVE CHARACTER and is subjected in his person to the consequences of his individual conduct. ***Key to understanding the 11th Amendment law IS TO FOCUS ON THE POLICY This is really just a way to balance competing interests; it’s a desire to protect state sovereignty while allowing the federal courts to act as guardians of constitutional rights by recognizing that federal courts can enjoin unconstitutional state conduct through the fiction of acting against the individual defendant It’s just an allegation of a constitutional violation, the Court isn’t talking about the merits here; it also would be federal statutory violation allegations So does he have to write the check on the state’s treasury? If YES, then it’s the same problem! Edelman v. Jordan (U.S. 1974) [federal STATUTORY CLAIM]: IL Dep’t of Human Services officers in statefederal program of aid; that they misadministered federal benefits; injunction requiring compliance with the law in the future & demand to pay applicants benefits that were wrongly withheld; the Supreme Court allowed the injunction (prospective) but NOT the payment to the applicants (it was “retroactive relief”) because the funds are coming from the state The Young fiction works for prospective relief but not retroactive relief in that case it was just an injunction; to the extent there’s a forward-looking injunction requiring compliance with the law it’s fine In order to pay funds wrongfully withheld is retrospective; measured against a past wrong—it’s damages for a past wrong; this would basically raid the treasury and give rise to all the problems that the 11 th Amendment aims to protect (it would to a virtual certainty come from the coffers of IL) Upshot: prospective relief permissible, retroactive relief is not Prospective relief may cost money; the reason no one was complying with the timeline in the case is because they didn’t have money! The Court says this is permissible; the ancillary effect of it costing the state money doesn’t matter ***This makes sense: when the relief is prospective, the state can budget or get out of the program BUT the state has no such flexibility when it’s simply being ordered to cough up money from the past Millikan v. Bradley (U.S. 1977): order for school desegregation case for remedial education & in-service training programs; state officials had to pay ½ of the costs; the Court upheld this it would apply prospectively to wipe out CONTINUING CONDITIONS OF INQUALITY produced by the inherently unequal dual school system; it’s okay because the programs are remedial, forward-looking to undo the effects of discrimination; this is prospective & permissible; it’s not an award to compensate & wipe the slate clean This comes up in employment cases—reinstatement is fine! You have to pay them! Back pay is not permissible 95 SUMMARY: can sue individual in official capacity seeking prospective relief when the allegation is that the individual violated federal law or the Constitution PROBLEMS ON EDELMAN Recent Elaborations of Ex Parte Young Va. Office for Protection & Advocacy v. Stewart (S. Ct. 2011): said Young allowed a federal court to hear a suit brought by 1 state agency against another state agency for injunctive relief under federal law Verizon Md. v. Pub. Serv. of Md. (U.S. 2002): for cases pursuant to Young, the Court only needs to ask whether the complaint alleges an ongoing federal law violation and seeks relief properly characterized as prospective The D under Young must be connected with the enforcement of the allegedly unconstitutional statute Indemnifying: the fact that a department claims liability, as opposed to the state, doesn’t mean that the state is open for suit under the 11th Amendment—it is only the entity’s potential legal liability, rather than its ability or inability to require a TP to reimburse it that’s relevant Supplemental Jurisdiction: Pennhurst II: a suit challenging the constitutionality of a state official’s action is NOT ONE AGAINST THE STATE (Young)—this doesn’t apply when the official violated only state law Congressional Power to Abrogate the 11th Amendment: under § 5 of the 14th Amendment, Congress can eliminate state’s sovereign immunity under the 11th Amendment by enacting legislation subjecting the states to suit Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer (U.S. 1976): authorized federal courts under Title VII to allow private individuals to sue state governments for money damages How does this happen? The Court said that the 14th Amendment came later than the 11th and that the terms of the 14th Amendment necessarily reflect limits on the states and § 5 says Congress can enforce this prohibition by appropriate legislation, so Congress can enact legislation subjecting the states to suit if acting pursuant to § 5 of the 14th Amendment What does Congress have to do to abrogate? There are stringent standards of statutory construction though: Atascadero (U.S. 1985): Congress must make its intention UNMISTAKABLY CLEAR & CA didn’t waive it in the Constitution because it wasn’t specific; Dellmuth v. Muth (U.S. 1989): need an UNEQUIVOCAL DECLARATION (explicit reference to either state sovereign immunity or the 11th Amendment) Why does this matter for 1983? Because since 1983 is a statute that Congress enacted pursuant to its § 5 power, Congress COULD abrogate the state’s 11th Amendment immunity; if it amended it to say “states are persons” there would be no 11th Amendment problem does it abrogate? NO Application to § 1983: did this abrogate state sovereign immunity? NO! Quern v. Jordan (U.S. 1979)—no explicit language that Congress intended it to abrogate; there’s no clear language in the statute itself 11th Amendment & Meaning of “Persons”: doesn’t apply to states in state court suits; whether states can waive States as “Persons” Will v. Mich. Dep’t of State Police, (U.S. 1989) [reading into the silence in 1983]: Will filed suit in state court alleging violations of the U.S. and Mi. Constitutions—1st Amendment retaliatory claim; he sued the Dep’t of State Police and the Director of Police in his official capacity; the COA determined that neither the state nor the official in his official capacity are a “person” under § 1983 (Congress didn’t intend this & can square with Monell because the municipal immunity was GONE at that time) If suing in state court, must look to whether states are persons because 11th Amendment doesn’t apply! Also states can waive their 11th Amendment immunity in federal court (so has a state that waived its 11th Amendment immunity a person?) Question is “person” to determine this question, the Court finds it necessary to discuss the 11 th Amendment Discussion As a matter of statutory construction, person doesn’t include states because Congress has to be explicit if it intends to alter the balance of power (CLEAR STATEMENT RULE EVEN THOUGH THIS ISN’T AN 11TH AMENDMENT CASE) As a matter of policy, to give a federal right in federal court but Congress couldn’t give a federal right in federal court against state defendants because the 11th Amendment would bar that suit; if states were persons, Congress would be giving a remedy only available in state court, but the point was to avoid state court! If states were persons, you’d have 1983 cases that would have to be brought in state court How to square with Monell 96 The case only applies to entities that are NOT part of the state for 11 th Amendment purposes—same as FN. 54 of Monell but backwards—holding limited to local government units which are not considered part of the state; here, it applies only to states or government entities that are considered arms of the state for 11th Amendment purposes Overlap: if you’re an arm of the state, then you are NOT a person BUT if you’re a municipality, you are a person; ***key: only way to determine who’s a person is by using 11th Amendment law States & state employees sued in their OFFICIAL CAPACITIES for DAMAGES are not “persons” subject to suit under § 1983 EXCEPT: FN. 10: A state official in his/her official capacity, when sued for injunctive relief, would be a person under § 1983 because official-capacity actions for prospective relief are not treated as actions against the state (Ex Parte Young) incorporating this case law in the definition of person (i.e. can’t sue President Martin in his official capacity for damages under 1983 because he’s not a person; you CAN bring an official-capacity suit against President Martin for injunctive relief because the suit will be against a “person”); ***even though the Court purports to be engaging in statutory construction, it hinges on the 11th Amendment (what is an arm of the state, what’s a person) and for official-capacity suits, turning on 11th Amendment cases; rules re: who is a person are the same as under the 11th Amendment (at bottom, look @ the policy of protecting the state’s treasury but preserving a way for federal courts to enforce the law) This is how you get an official under state law engaging in a pattern of constitutional violations Dissent (Brennan + Marshall, Blackmun & Stevens): this isn’t a fair reading of § 1983 Dissent (Stevens): we allow attorney’s fees against states Cant Sue U of M in Federal Court or State Court? No. David Rudd for Damages? No. David Rudd for injunction to comply w/ constitution. Individual v. Official Capacity Suits Hafer v. Melo (U.S. 1991): Hafer sought election and in her campaign she promised to fire people who “bought” their jobs; she did fire them; it was an employment decision; the 3d Cir. determined that this was a suit against Hafer in her individual capacity State officials sued in their INDIVIDUAL CAPACITIES challenging actions she took as an official are “persons” for § 1983 purposes The P was trying to recover damages from HER, not the state’s treasury Issue: whether the dicta in Will talking about acting in official capacity was how it acted or was sued the Court explains it’s capacity in which the person is SUED, not acting When person sued in official capacity, the state is the party in interest Difference A suit against a state official in her official capacity should be treated as a suit against the state. When the official is sued in this capacity in federal court (if she dies or leaves office), her successor automatically assumes her role in the litigation. In these suits, the entity’s policy or custom must have played a part in the violation, thus there aren’t immunities available. (only those for the entity itself) For individual capacity suits, need not establish a policy/custom & the individual may assert personal immunity. State’s treasury not implicated so there’s no need to look at ex parte Young (suing them for damages is fine) The person still has QUALIFIED immunity Hafer tried to distinguish between functions outside official authority & not essential to the operation of government and those within the authority & necessary for the function of government (the Court doesn’t buy this) Immunity from suit under § 1983 is predicated upon a considered inquiry into the immunity historically accorded the relevant official @ common law and the interests behind it; the official seeking absolute immunity must show that it is justified for the government function @ issue Q.I. for administrative functions Questions on Will & Hafer ***footnote * & notes: P is well-advised to indicate the capacity in which you are suing someone in your complaint (say “in his/her individual capacity seeking damages & in his official capacity seeking injunctive relief”); if not explicit, the court will try to figure out what you mean 97 98