The Lost Generation: Hemingway, Aldington, Fitzgerald Essay

advertisement

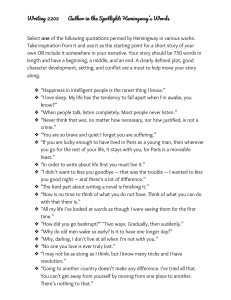

МИНИСТЕРСТВО НАУКИ И ВЫСШЕГО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ КЕМЕРОВСКИЙ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ Институт филологии, иностранных языков и медиакоммуникаций Кафедра переводоведения и лингвистики Реферат Тема реферата: «The ‘Lost Generation’: Ernest Hemingway, Richard Aldington, F.S. Fitzgerald» Подготовила: Туранова Эльвира Студентка группы ПП-201 Факультет: ИФИЯМ Проверила: Башкатова Юлия Алексеевна г.Кемерово 2022 г. Содержание 1 Введение ...................................................................................................................................... 3 2 Ernest Hemingway ....................................................................................................................... 4 3 Richard Aldington ........................................................................................................................ 5 4 F.S. Fitzgerald .............................................................................................................................. 7 5 Заключение. A new lost generation ............................................................................................ 8 6 Использованная литература ...................................................................................................... 9 2 Введение Lost Generation, a group of American writers who came of age during World War I and established their literary reputations in the 1920s. The term is also used more generally to refer to the post-World War I generation. The generation was “lost” in the sense that its inherited values were no longer relevant in the postwar world and because of its spiritual alienation from a United States that, basking under Pres. Warren G. Harding’s “back to normalcy” policy, seemed to its members to be hopelessly provincial, materialistic, and emotionally barren. The term embraces Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, John Dos Passos, E.E. Cummings, Archibald MacLeish, Hart Crane, and many other writers who made Paris the centre of their literary activities in the 1920s. They were never a literary school. Gertrude Stein is credited for the term Lost Generation, though Hemingway made it widely known. According to Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast (1964), she had heard it used by a garage owner in France, who dismissively referred to the younger generation as a “génération perdue.” In conversation with Hemingway, she turned that label on him and declared, “You are all a lost generation.” He used her remark as an epigraph to The Sun Also Rises (1926), a novel that captures the attitudes of a hard-drinking, fast-living set of disillusioned young expatriates in postwar Paris. In the 1930s, as these writers turned in different directions, their works lost the distinctive stamp of the postwar period. The last representative works of the era were Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night (1934) and Dos Passos’s The Big Money (1936).[1] 3 Ernest Miller Hemingway Ernest Miller Hemingway was an American author and journalist. He was born on July 21, 1899 in Oak Park, Illinois, where he was raised. He died on July 2, 1961 in Ketchum, Idaho, where he committed suicide. Hemingway's economical and understated style had a strong influence on 20th-century fiction, while his life of adventure and his public image influenced later generations. Hemingway produced most of his work between the mid-1920s and the mid-1950s, and won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954. He published seven novels, six short story collections, and two non-fiction works. Three novels, four collections of short stories, and three non-fiction works were published posthumously. After finishing high school, Hemingway reported for a few months for The Kansas City Star, before leaving for the Italian front to enlist with the World War I ambulance drivers where he was wounded in 1918 and returned home. Hemingway's experiences in wartime formed the basis for his novel A Farewell to Arms. In 1922, he married Hadley Richardson, the first of his four wives. The couple moved to Paris, where he worked as a foreign correspondent, and fell under the influence of the modernist writers and artists of the 1920s "Lost Generation" expatriate community. The Sun Also Rises, Hemingway's first novel, was published in 1926. Hemingway married Pauline Pfeiffer after his 1927 divorce from Hadley Richardson. However this marriage was also unsuccessful and the couple divorced after Hemingway returned from the Spanish Civil War where he had been a journalist. Drawing from his experience in the Spanish Civil War, Hemingway published For Whom the Bell Tolls. He married his third wife, Martha Gellhorn in 1940. They separated when he met Mary Welsh in London during World War II. Shortly after the publication of The Old Man and the Sea, one of his masterpieces, in 1952, Hemingway went on safari to Africa, where he was almost killed in two successive plane crashes that left him in pain or ill health for much of the rest of his life. Hemingway had permanent residences in Key West, Florida, and Cuba during the 1930s and 1940s, but in 1959 he moved from Cuba to Ketchum, Idaho, where he put an end to his life in the summer of 1961.[2] 4 Richard Aldington Richard Aldington was prominent in several literary capacities; most notably as a founding poet of the Imagist movement and as a novelist who conveyed the horror of World War I through his written works. He was also a prolific critic, translator, and essayist. Though he considered his novels to be his most important works, he received much critical attention for his biographies of such contemporaries as Lawrence of Arabia and D.H. Lawrence. Aldington began his literary career in London as a part-time sports journalist after leaving college and quickly became part of an influential circle of British writers that included William Butler Yeats and Walter de la Mare. However, he became disillusioned with the literary scene after returning from battle in World War I, and he moved to France and lived the life of an expatriate writer abroad. Aldington first received critical attention as a poet whose works were dubbed Imagist, a style marked by a minimalist free verse that incorporated succinct and vivid images. This movement became prominent around 1912 primarily because Aldington's friend, the poet Ezra Pound, promoted it and its practitioners tirelessly. Other popular poets of Aldington's circle who participated in the movement included H.D. (Aldington's wife, Hilda Doolittle), James Joyce, D.H. Lawrence, and William Carlos Williams. Aldington's strain of Imagist poetry is heavily influenced by Japanese art and contains many references to Greek tragedies and myths. These Greek influences are especially prominent in The Love of Myrrhine and Konallis, a prose piece describing a “Sapphic” love affair, which critic May Sinclair of the English Review says contains “the most exquisite love poems in the language.” Glenn Hughes in Imagism & the Imagists characterizes Aldington's poems as being full of “long and voluptuous” cadences that exhibit “imagery weighted with ornament.” Douglas Bush in Mythology and the Romantic Tradition in English Poetry compares Aldington's poetry with H.D.'s by noting that “in intention and technique his early Hellenic-Imagist poems were much the same as H.D.'s, but with a more diffuse softness, a more openly Victorian weariness and nostalgia.” Aldington interrupted his writing career to serve in the army during World War I. The trauma of modern trench warfare affected him deeply, and his post-war writings convey an extreme pessimism that some critics have attributed to shell shock. Aldington's writing shifted “from Imagism to verse of the Pound-Eliot kind, and then to the novel,” according to Bush. Noting the effect of the war on Aldington's writing, Bush concludes that he “made a career of disillusioned bitterness.” His first writings about his war experiences were the poetry collections Images of War and Images of Desire, both published in 1919. Still evident are Aldington's earlier Greek influences, but they are now infused with a melancholy tone. A Times Literary Supplement reviewer notes that in these poems Aldington increases the contrast “between the integrity and cleanliness of the Greeks ...and the dingy muddle of the present.” Hughes remarks that in Images of War that we “see and feel the cataclysm of 5 bombardment, the loneliness of ruined fields and villages.” Critics note that Aldington's bitterness affected his nonfiction writing as well. Though perhaps unfairly biased by his close friendship T.E. Lawrence, Robert Graves in a review of Aldington's biography Lawrence of Arabia, noted that, “instead of a carefully considered portrait of Lawrence, I find the self-portrait of a bitter, bedridden, leering, asthmatic, elderly hangman-of-letters.” Aldington's somewhat autobiographical novel, Death of a Hero, published ten years after the war, graphically depicts the impact of war on a soldier's civilian life. The story explores the alienation and isolation of a young soldier, George Winterbourne, upon his return home on a leave of absence. Readers know from the outset that Winterbourne is eventually killed in battle, and the book outlines the events and social conditions that lead up to the tragedy. Death of a Hero is regarded as an important first-hand account of war on par with Erich Maria Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front and Ernest Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms. London Times critic Kay Dick calls Death of a Hero a “very angry” and “virulent” work that demonstrates Aldington's “near paranoic hatred of his fellow man.” Despite this, Aldington's account of the horrors of trench warfare seems accurate, Dick concludes; “the mud, the rats, the gas.... It is gruesome and shocking, but it is true.” Though L. P. Hartley of the Saturday Review calls the novel a failure for its “grotesquely unfair” portrayal of the Victorian middle classes and its exaggerated characters, A. B. Parsons of the Nation says that Death of a Hero “takes its place among the half dozen superb stories of the war that will not let men forget.” Many critics in retrospect forgive Aldington's pessimism and the negativity of his work. Clifton Fadiman, in a New Yorker review of Aldington's autobiography, Life for Life's Sake, calls Aldington's reminiscences “good gossip,” the work of the “typical literary man” in the first half of the twentieth century. Though Aldington does not enjoy as widespread a popularity today as some of his contemporaries, his writings remain a good example of the thoughts and style of his generation. Terry Comito writes in Dictionary of Literary Biography that Aldington “had a gift for evoking with considerable fluency large, uncomplicated emotions that readers have often found easy to share, and his champions frequently cite Aldington's verse in order to argue that contemporary poetry need not be obscurely intellectual.”[3] 6 F. S. Fitzgerald American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940) rose to prominence as a chronicler of the jazz age. Born in St. Paul, Minn., Fitzgerald dropped out of Princeton University to join the U.S. Army. The success of his first novel, This Side of Paradise (1920), made him an instant celebrity. His third novel, The Great Gatsby (1925), was highly regarded, but Tender is the Night (1934) was considered a disappointment. Struggling with alcoholism and his wife’s mental illness, Fitzgerald attempted to reinvent himself as a screenwriter. He died before completing his final novel, The Last Tycoon (1941), but earned posthumous acclaim as one of America’s most celebrated writers. Born in St. Paul, Minnesota, Fitzgerald had the good fortune—and the misfortune— to be a writer who summed up an era. The son of an alcoholic failure from Maryland and an adoring, intensely ambitious mother, he grew up acutely conscious of wealth and privilege—and of his family’s exclusion from the social elite. After entering Princeton in 1913, he became a close friend of Edmund Wilson and John Peale Bishop and spent most of his time writing lyrics for Triangle Club theatrical productions and analyzing how to triumph over the school’s intricate social rituals. He left Princeton without graduating and used it as the setting for his first novel, This Side of Paradise (1920). It was perfect literary timing. The twenties were beginning to roar, bathtub gin and flaming youth were on everyone’s lips, and the handsome, witty Fitzgerald seemed to be the ideal spokesman for the decade.[4] 7 Заключение. A new lost generation The next generation, sometimes referred to as 'Generation Z' or 'Gen Z', includes children and young people born after 1995/1996. Also known as the 'iGeneration' they are the first digital natives: they have grown up with smartphones and tablets, and most have internet access at home. While, in the EU, they are the most diverse generation when it comes to their origins, and best educated, in terms of level of education, they are the most vulnerable, including on the labour market. They are the generation most at risk of poverty, and worst affected by the lack of intergenerational earning mobility. In addition, they have been hardest hit by the coronavirus crisis, following school closures and also job losses. The negative trends this generation was facing prior to the pandemic solidified during the outbreak and the lockdown measures. The well-being, educational success and labour market integration of this generation have a major impact on the general well-being of society, as well as on productivity growth, and thus on the entire economy now and in the future. It will, however, be another 15 years before this generation, along with the 'Millennials' (born between 1981 and 1995/1996) form the majority in the voting age population across the EU, and their views, expectations and attitudes are taken into consideration when designing policies. In this context, policies must address Generation Z from a young age as active citizens who need to be both protected and empowered. In the von der Leyen Commission more than half the Commissioners have been entrusted with tasks that directly address challenges for this generation, ranging from access to quality education, health, housing, nutrition and labour markets to combating poverty and protecting children's and young people's rights. This is an opportunity to design comprehensive policies that cut across sectors and that address the entire generation under the age of 22/24 in a multidimensional way. It is also a way to include children and young people in the democratic process and monitor their progress across multiple indicators in relation to the United Nations sustainable development goals. Stronger pro-child and pro-youth policies can help to achieve more balanced and efficient welfare states that genuinely protect the entire population.[5] 8 Использованная литература 1.https://www.britannica.com/topic/Lost-Generation 2.https://www.myenglishpages.com/english/reading-ernest-hemingway-biography.php 3. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/richard-aldington 4. https://www.history.com/topics/roaring-twenties/f-scott-fitzgerald 5. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2020)659404 9