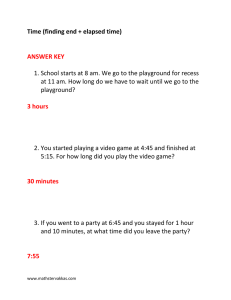

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/298526069 A community built playground in Tel-Aviv Article · January 1999 CITATION READS 1 68 1 author: Yodan Rofé Ben-Gurion University of the Negev 66 PUBLICATIONS 780 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Public open spaces in the city: activities, functions and standards View project Learning from the development patterns of informal settlements how to improve city planning View project All content following this page was uploaded by Yodan Rofé on 09 February 2019. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. A Community Built Playground in Tel-Aviv YODAN Y. ROFE This field note reviews the immediate and wider significance of a neighbourhood playground built in 1990 by the local community from a deprived area of Tel-Aviv, Israel in partnership with its municipality. The success of the project is manifest in its continued use, upkeep and maintenance by the local community, and in recent moves by the city of Tel-Aviv to extend the initiative in conjunction with local schools, in an attempt to foster children's involvement with, and care for, their immediate environment. Introduction Before: A Dilapidated Community Space This is the story of the transformation of a popular community space from a spartan and dilapidated play environment into a public garden and children's playground in a low-income neighbourhood of Tel-Aviv in Israel. This achievement was made possible by a unique co-operation between pro­ fessionals, city officials and the people of the community. In this field note, I describe the prior condition of the area, the circum­ stances that led to the project, the design of the playground and its construction, and the outcomes of the project in the neighbour­ hood and beyond . The site of the playground was a sandy lot, roughly in the centre of the neighbourhood, along a major public transit street. It was strewn with old metal play equipment and lacked trees and shade. Yet it was still heavily used despite its 'neglected' state, given the absence of any other play space in the vicinity. For local residents, renewal of the playground was of functional and symbolic significance. They saw it as an important local resource (use value) within the neigh­ bourhood. The city administration's negation of its periodic promises to renew the Figure 1. Before: state of the playground before the beginning of the project. (Source: Jimmy Jolley) BUILT ENVIRONMENT VOL 25 NO 1 61 PLAYGROUNDS IN THE BUILT EN VIRONMENT playground was perceived as an indication of the city's disregard for the neigh­ bourhood (symbolic significance). I became involved with the issue after moving to the neighbourhood in 1988. An opportunity for progress was presented when I approached Jimmy Jolley, the playground designer who had been invited by Aenahem Granoff, Chair of the Israeli chapter of the International Association for the Child's Right to Play (IPA) to help build two playground projects in Israel. The rationale for building playgrounds with the community is both economic and social. From an economic viewpoint, one is able, by using volunteer labour, and materials donated or recycled locally, to build a rich and interesting play environ­ ment for much less cost than if contracted privately. Socially, the process of building the playground helps to bring people in the community together, and fosters a sense of shared ownership. In turn, this sense of ownership helps to reduce vandalism, and to ensure better maintenance once the project is completed. During: The Design and the Process of Construction Jolley tries to involve local children and adults from the initial design stage of playground construction. However, at the outset, neither the community nor the municipality were active participants in this 'local project'. On one hand, because of the legacy of mistrust between the people and the municipality, local people were reluctant to become involved until construction had started. On the other hand, the Head of the Parks Department, unsure of the seriousness of the project, wanted us to present a design and an estimate before approving funds for the project. Local participation was contingent on the initial progress of the playground designers. In this respect, the project is unique among 'community built' playgrounds. Furthermore, the project is unique in Israel where 'community built' playgrounds tend to focus on schoolyards and to have the support of a strong community organization - the school's parent association - which is responsible for organizing the volunteer work. The design of the playground was simple, and was intended to allow for various groups to use the playground simul­ taneously. We kept the existing informal paths, which defined two major play areas, a separate swing area, and two seating areas. One play area is for toddlers, while the other, with more challenging play struc­ tures, is for older kids. One seating area is central with a view to the sea, while the other is near the major street entrance underneath a pergola. Furthermore, within the pergola, facilities for babies were planned to allow them to play under the close supervision of their parents. The first contingent condition for participation had been met and municipal funds were approved on the basis of this design. The first week was spent preparing the site by landscaping and digging the trenches for irrigation lines. Thereafter, more and more local people joined in, particularly at the pOint where the play equipment was being introduced. Children came first, curious to see what was going on, and willing to help. Soon after came the parents, both mothers and fathers. Last came the teenagers, who stood on the sidelines not wanting to appear too enthusiastic or to lose face by seeming to do something for nothing. At times we had over fifty people working together on the site, some of them adults who grew up in the neighbourhood and now lived elsewhere, but who still came to visit their parents and friends. Restaurant owners in the vicinity sent food and drinks for the workers. For a period of two weeks the playground became a real focus of the community (figure 2). Perhaps the most important moment in the construction process was the arrival of the trees. The Parks Department sent us BUILT ENVIRONMENT \'VL_ fully mature trees : \\':: centimetres in di amet be dug, and the treec:. n place. The transforma immediate. In the desi the blank side wall falin _ was envisaged as a m;.. cheerful background to f play structures were c cessfully applied for hu· Aviv Art foundation, an local artist, painted the .. registered in the public aT: ~ of Tel-Aviv (figure 3). Mr. Haim Massou ri, \·yorker, and local acti\ diligently during the co upon himself to be the UT. of the playground. He carr. watered the trees, and m 'vIENT VOL 25 NO 1 A COMMUNITY BUILT PLA YGROUND IN TEL-AVIV fully mature trees: with trunks more than 20 centimetres in diameter, deep holes had to be dug, and the trees had to be hoisted into place. The transformation of the space was street cleaners did their job properly. In a sense he nursed it along the most difficult months after construction until it became firmly established. Figure 2. During: moments in the process of constructing the playground. (Source : Jimmy Jolley) immediate. In the design of the playground, the blank side wall facing the playground was envisaged as a mural, to provide a cheerful background to the space. Once the play structures were completed, we suc­ cessfully applied for funds from the Tel­ A viv Art founda tion, and Carlos Basanta, a local artist, painted the mural, which is now registered in the public art guide of the city of Tel-Aviv (figure 3). Mr. Haim Massouri, a retired metal worker, and local activist, who worked diligently during the construction, took it upon himself to be the unofficial custodian of the playground. He came there every day, watered the trees, and made sure that the BUILT ENVIRONMENT VOL 25 NO 1 After: User Evaluations and Feelings about the Playground Neighbourhood residents who participated in the construction were immensely proud of their achievement. They began to appreciate the uniqueness and interest of the play­ ground for the kids. The children them­ selves felt that they owned it. They had no doubts that it was the best playground in the city. The last doubters in the community, who continued to believe that it was merely a way for the city to get the neighbourhood to agree to a cheaper and less 'beautiful' playground, were finally convinced by the exposure that the neighbourhood and the 63 PlAYGROU N DS IN THE BUILT ENVIRONMEN T process received in the local and national press. This pride and sense of ownership, as well as the use-value of the dense play environment, were important for the con­ tinued upkeep of the playground . Although undergoing wear and tear due to heavy use, none of the structures in the playground were vandalized, nor was the mural defaced by graffiti - this in a neighbourhood where there is usually little respect for public property. However, because the equipment is unique and does not conform to any now using the park, it is just another park built by the city, and therefore they do not see themselves as responsible for it, or able to contribute to it in any way. Wider Outcomes, and Lessons to be Learned From the Project The publicity surrounding the success of this playground helped secure support for two more community built playground projects in Israel. In parallel, Jolley, the playground designer, held a short workshop local environment. "'"T project to transform parents, teachers it!'. projects have beer _­ by architects Yael -,(_ who participated : , Saadia Mandl. Each communi t\· ::' its place and the eire: possible. On the o c!' this have been bui!, idea is certainly tran to be adapted to i attitudes. Tremen do...., ment is needed frorr: project. In our case was expended in aCL were promised b\" seemed tha t the co:'.,. against all the ac(__ departments, as d ili Figure 3. After: the completed playground. (Source: Anat Basanta) standard design, there has been no regular maintenance plan for tasks such as replacing torn tyres or re-tightening the chains and wires of bridges. In recent years, with population changing in the community, there seems to be less involvement of people in the playground. For the kids and parents 64 on designing and building community playgrounds at the Faculty of Architecture in the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem. More recently, the city of Tel­ Aviv decided that building playgrounds with the community would be a good way to educate kids to care more about their BUILT ENVIRON ME NT VOL 25 NO 1 BUILT ENVIRO NMENT VOL ~~ A COMMUNITY BUILT PLA YGROUND IN TEL-A VIV local environment. The city has initiated a project to transform ten schoolyards by parents, teachers and children. Four of these projects have been built so far, supervised by architects Yael Mann, one of the students who participated in the workshop, and Saadia Mandl. Each community built project is unique to its place and the circumstances that make it possible. On the other hand, projects like this have been built all over the world. The idea is certainly transferable, although it has to be adapted to local circumstances and attitudes. Tremendous energy and commit­ ment is needed from the organizers of the project. In our case, much of this energy was expended in accessing the support we were promised by the city. At times it seemed that the construction process went against all the accepted practices of city departments, as did the pace at which we BUILT ENVIRONMENT VOL 25 NO I View publication stats were working (building a playground in three weeks). This 'loss' of energy to admini­ strative tasks, could be avoided by estab­ lishing a special municipal programme for community playgrounds that provided design know-how and logistical support. While not all communities may be interested in building such a playground, it is a means for neighbourhood groups who seek to mobilize and unite the community. The continued success of this playground shows, I believe, that the city has much to gain from more projects like these, particularly in low­ income areas. In the end, building the playground has been an incredibly re­ warding experience for all participants. It is still a source of pride to know that we have been able to improve an area in our neigh­ bourhood that had been neglected for years, and to foster the sense of community and collective satisfaction that it generates. 65