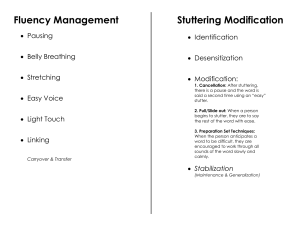

A Review of Stuttering Intervention Approaches for Preschool-Age and Elementary School-Age Children Aimee Sidavi Renee Fabus Brooklyn College, Brooklyn, NY T his article summarizes the literature regarding different stuttering intervention approaches that have been used with preschool-age and early school-age children. The following information for each approach is presented: name, purpose, components, and limitations. Stuttering treatment is a contentious issue for speech-language pathologists (SLPs) and has posed a pressing challenge in the field of speech-language pathology for decades (J. C. Ingham & Riley, 1998; Yaruss, Coleman, & Hammer, 2006). There are many treatments for stuttering; however, there is little agreement as to which should be used and when treatment should begin (especially for preschool- and school-age children). Treatment for stuttering includes ABSTRACT: Purpose: This article describes different intervention approaches for preschool and school-age children who stutter, including the name of the approach and its components and limitations. Method: A review of the literature was conducted to summarize and synthesize previously published research in the area of stuttering treatment. The goal of this literature review was to increase the clinician’s knowledge base about different intervention approaches that are used with children who stutter. If a clinician has an extensive understanding of intervention techniques, then he or she can conduct well-developed therapy sessions. Conclusion: Despite the increasing size of the literature in the area of stuttering, there remains a dire need for evidence-based intervention approaches. KEY WORDS: stuttering, intervention approaches, preschool children, school-age children, literature review 14 CONTEMPORARY ISSUES various techniques and methods: indirect and direct (R. J. Ingham & Cordes, 1998), stuttering modification (Guitar & Peters, 1980; Peters & Guitar, 1991), fluency shaping (Blomgren, Roy, Callister, & Merrill, 2005; Guitar, 1998), Lidcombe Program, altered auditory feedback (Armson & Stuart, 1998; Hargraves, Kalinowski, Stuart, Armson, & Jones, 1994; Howell, Sackin, & Williams, 1999; Van Borsel, Reunes, & Van den Bergh, 2003), self-modeling (Webber, Packman, & Onslow, 2004), and regulated breathing (Andrews & Tanner, 1982; Ladouceur, Cote, Leblond, & Bouchard, 1982; Woods & Twohig, 2000). Understanding the various treatment approaches can pose a challenge for clinicians. To properly select the appropriate treatment method, clinicians must have access to all of the treatment options. The purpose of this article is to review the various treatment methods used by clinicians to help treat preschool- and school-age children’s stuttering. A review of existing literature serves many functions, including summarizing findings, identifying consistencies and inconsistencies in the research available, and identifying implications for future research and practice (Bothe, Davidow, Bramlett, Franic, & Ingham, 2006). A literature review provides clinicians with some of the information necessary for evidence-based practice (Bothe et al., 2006; Yaruss et al., 2006). Moreover, assessing treatment methods has helped researchers establish new approaches for the design and conduct of more rapid clinical studies. Initiating Treatment There is much controversy regarding when intervention should begin for preschool- and school-age children who INCC OMMUNICATION SCIENCE AND D ISORDERS • Volume 37 • 14–26 • Spring 2010 • Spring 2010 © NSSLHA ONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN C OMMUNICATION SCIENCE AND D ISORDERS • Volume 37 • 14–26 1092-5171/10/3701-0014 Downloaded from: https://pubs.asha.org 168.232.62.66 on 02/18/2022, Terms of Use: https://pubs.asha.org/pubs/rights_and_permissions stutter. The matter is complicated because of the high percentage (approximately 70%) of children who recover spontaneously (e.g., Finn, 1996; Peters & Guitar, 1991). Yairi and Ambrose (1999) stated that 74% of children who stutter recover naturally within the first 2 years of onset. The controversy concerning when to begin treatment reflects different philosophies regarding the nature of the disorder. Curlee and Yairi (1997), for example, suggested “active monitoring” for 2 years postonset rather than active intervention. There are many variables that affect treatment time; therefore, knowledge of the variables is essential to determine when treatment for preschool-age children should begin (Rousseau, Packman, Onslow, Harrison, & Jones, 2007). Although guidelines have been developed for the timing of several treatment programs (e.g., the Lidcombe Program; Packman, Onslow, & Attanasio, 2003), it is important to identify the child’s concomitant disorders (e.g. language and phonology) in order to predict treatment time and decide when to begin treatment for early intervention (Rousseau et al., 2007). Treatment Reliability An important aspect of assessing various treatment programs is whether the treatment was administered correctly. This aspect determines whether the treatment was effective as reported in the literature (Conture & Guitar, 1993). Siegel (1990) stated that replication is the most rigorous test of reliability. In a number of studies, researchers have reported that replication in treatment efficacy research has been overlooked (Attanasio, 1994; Meline & Schmidt, 1997; Muma, 1993; Onslow, 1992). Muma (1993), for example, surveyed 1,712 studies in the Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders and the Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. Based on statistical analysis, he claimed that Type I (false positive) and Type II (false negative) errors were likely to be found in 50–250 findings. In addition, Onslow (1992) reviewed the literature on stuttering intervention and reported that few studies have been replicated. These findings could be misleading the development of treatment in the field, indicating the necessity for further replication studies. Indirect and Direct Approaches Indirect approaches to treating stuttering involve modifying the child’s environment rather than working directly with the child (R. J. Ingham & Cordes, 1998; Richels & Conture, 2007). Indirect therapy approaches are often implemented when the child is not aware of, or is frustrated by, his or her stuttering. The aim of indirect therapy is to facilitate fluent speech through changes in the environment and modifications to parents’ speaking patterns. Indirect methods target children’s attitudes, feelings, fears, and language in daily interactions (e.g., pragmatics), and may result in a reduction of the child’s speaking rate (Conture, 2001; Gottwald & Starkweather, 1995; Guitar, 1998; Shapiro, 1999; Starkweather, Gottwald, & Halfond, 1990). This is directly related to the diagnostic theory of stuttering, which states that stuttering is a result of parental attention to the child’s disfluencies (Bernstein Ratner & Tetnowski, 2006). R. J. Ingham (1993) noted that many clinicians favor indirect approaches because they place less pressure on the child; however, she claimed that these practices were not supported by evidence. Furthermore, she noted that indirect treatments have too many variables and are difficult to measure objectively. Direct approaches, on the other hand, target the child’s individual speech behaviors (R. J. Ingham & Cordes, 1998; Richels & Conture, 2007). Direct therapy approaches are often implemented when children are aware of and/or frustrated by their stuttering, as well as when they exhibit secondary behaviors (Coleman, Yaruss, Butkiewicz, & Roccon, 2005). Direct treatment may be professionally directed or parent directed; that is, either the SLP or the parent may target the child’s speech disfluencies. Behavior modification techniques have yielded positive results in various studies (e.g., Onslow, Andrews, & Lincoln, 1994; Onslow, Packman, Stocker, van Doom, & Siegel, 1997). Some examples of direct treatment include modeling reduced speaking rate, increasing pauses during turn taking, allowing the child to finish his or her statement without interruption, and relaxed breathing techniques (Hill, 2003; Kelly, 1995; Walton & Wallace, 1998; Zebrowski, 1997; Zebrowski, Weiss, Savelkoul, & Hammer, 1996). Specific programs include the Lidcombe Program (Onslow, 1997) and Gradual Increase in Length of Complexity of Utterance (Ryan & Ryan, 1983). Onslow (1995), however, noted a decline in the effectiveness of behavior modification techniques after 5 years of age. Some clinicians favor direct approaches to eliminate stuttering behaviors (Adams, 1984; Prins & Ingham, 1983; Shine, 1984). Bernstein Ratner (1997) indicated that clinicians have favored indirect approaches for early stuttering (e.g., Cooper & Cooper, 1985; Cooper & Rustin, 1985). She stated that direct treatment may not be suitable for children with an average age of 2;6 (years;months). Nonetheless, it has become increasingly popular to begin shortterm indirect treatment and proceed, if necessary, to direct treatment (Coleman et al., 2005). Family-Focused Treatment, Counseling, and Support Groups For treatment of preschool children who stutter to be successful, parental intervention is essential (Lawrence & Barclay, 1998). There are two major components involved in parental intervention: (a) parental knowledge and feelings about stuttering in general, their child who stutters, and themselves, and (b) parental behaviors with their child while stuttering and without stuttering (Shapiro, 1999). Parents are advised not to criticize the child, not to constantly remind the child to speak slower, and not to repeat words that were said disfluently (Lawrence & Barclay, 1998). Moreover, Peters and Guitar (1991) and Van Riper (1973) suggested diminishing time pressure, interruptions, rapid speech rates, hectic or unpredictable schedules, punishments, and guessing what the child intends to say. Parents need to be educated about what they can contribute to the Sidavi • Fabus: Stuttering Intervention Approaches Downloaded from: https://pubs.asha.org 168.232.62.66 on 02/18/2022, Terms of Use: https://pubs.asha.org/pubs/rights_and_permissions 15 development of their child’s communication and fluent speech (Shapiro, 1999). Yaruss et al. (2006) described a family-focused treatment approach for preschool-age children (between the ages of 2 and 6) who stutter. The treatment included parent-focused strategies to help parents alter their speaking patterns and reduce their anxiety about stuttering and child-focused strategies meant to help children modify their behaviors and communication attitudes. Overall, the treatment method targeted improved speech fluency, effective communication skills, and healthy communication attitudes for both parents and children. The efficacy of the treatment was validated with a preliminary study examining the outcomes of treatment for 17 preschool-age children. All children demonstrated gains in fluency and maintained the gains at the long-term follow-up. Treatment groups for both children and parents can also be implemented to help the child achieve fluency (Richels & Conture, 2007). Richels and Conture (2007) explained that whereas child treatment groups help the child achieve fluency, parent treatment groups prepare parents for their child’s therapy expectations and goals. To increase participation from all members, child groups should be limited to 5 children. Throughout the session, the SLP should use a slow rate of speaking and syntactically appropriate utterance lengths and should not interrupt the child or modify the child’s speech. The session should begin with a conversation so the clinician can monitor the child’s disfluencies within a 100-word sample. The disfluency count allows the clinician to monitor the child’s progress. The parents in Richels and Conture (2007) were advised to purchase a book, Stuttering and Your Child: Questions and Answers (Conture, 2002), and a video, Stuttering and Your Child: A Videotape for Parents (Conture, 1997). In addition, the parents were given various strategies and suggestions to facilitate their child’s fluency: use slower rates of speech, use shorter sentences, do not interrupt your child, avoid correcting your child, and avoid reprimanding your child for producing disfluencies (Richels & Conture, 2007). Counseling is another important aspect to the treatment of children who stutter that can help both parents and children deal with the necessary emotional adjustments. Rollin (2000) defined counseling as “a dynamic process that involves a complex interaction between and among people” (p. 2). Furthermore, Luterman (2001) stated that counseling is “a clinician trying to help a client manage change” (p. 9). Counseling, however, has received minimal attention in the stuttering literature (DiLollo & Manning, 2007). Luterman and Shames (2000) suggested that perhaps it is the clinician’s discomfort with counseling children and their parents that has contributed to the scarcity of research in this area. Counseling children, especially preschool- and schoolage children, may be a difficult task (DiLollo & Manning, 2007). The SLP can begin by listening to a narrative, or story, which often reflects the child’s anxiety, tension, and fear (Payne, 2002). The narrative can then be used to externalize the problem, making the stuttering a separate identity. In this way, the stuttering does not become an 16 CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN COMMUNICATION SCIENCE AND internal trait; that is, the disorder does not become a point of identification for the child (Payne, 2002; White & Epston, 1990). Parents of children who stutter may face many emotional reactions (Crowe, 1997). Counseling parents should initially focus on the emotional adjustments such as grief, fear, anxiety, guilt, isolation, denial, and depression (Crowe, 1997; Kubler-Ross, 1969; Manning, 2001). Clinicians begin by listening and acknowledging the emotional responses. The clinician refocuses the parents’ energy, perhaps by making them more active in the treatment process (e.g., Lidcombe Program) or by encouraging them to join support groups. Support groups and self-help groups are playing a larger role in the recovery process of individuals who stutter (Bradberry, 1995; Krall, 2001; Ramig, 1993; Yaruss, Quesal, Reeves, et al., 2002). Support groups provide members with newsletters, literature, and other information about stuttering (e.g., treatment programs). Members may also be provided with advice about treatment programs. These factors play an important role for both the SLP and the individual who stutters. The information received from the support group may play a large role in the attitudes and beliefs the individual may have toward a certain treatment option. The SLP must therefore become an active member in these groups and become acquainted with the information distributed to the members (Yaruss, Quesal, & Murphy, 2002). The National Stuttering Association (NSA; http://www. nsastutter.org) is the largest self-help support group in the United States for individuals who stutter. The NSA-Kids division has many chapters for both preschool- and schoolage children. They have several local support groups and have NSA Youth Days for children and their families. NSA Youth Days are events that bring individuals who stutter together in a supportive environment. FRIENDS (http:// www.friendswhostutter.org) is another national organization by the National Association of Young People Who Stutter that helps children, teenagers, and their families cope with stuttering. FRIENDS has a bimonthly digest titled Reaching Out that provides information based on the experiences of young people who stutter. In addition, the association holds conferences and annual conventions so families and friends can share their experiences. These are just a few ways that parents, children, and therapists can become active members in children’s treatment process. Stuttering Modification Versus Fluency Shaping There are two therapeutic techniques used when treating stuttering—stuttering modification and fluency shaping. Stuttering modification aims to reduce speech-related avoidance behaviors, fears, and negative attitudes (Guitar & Peters, 1980; Peters & Guitar, 1991). The goal of stuttering modification is to modify stuttering moments by decreasing the tension so the stuttering is less severe and the fear or avoidance behaviors of stuttering are eliminated (Blomgren et al., 2005; Guitar, 1998). This may be accomplished by reducing struggle behaviors, tension, and the rate of stuttering (Guitar & Peters, 1980). Underlying this approach is DISORDERS • Volume 37 • 14–26 • Spring 2010 Downloaded from: https://pubs.asha.org 168.232.62.66 on 02/18/2022, Terms of Use: https://pubs.asha.org/pubs/rights_and_permissions the notion that stuttering results from various avoidance behaviors and feared situations (Guitar & Peters, 1980; Peters & Guitar, 1991). Stuttering modification approaches have been referred to in various ways in the literature: “stutter more fluently” (Gregory, 1979, p. 2) and “those that manage stuttering” (Curlee & Perkins, 1984, p. iii). Manning (1999) contended that although stuttering modification may decrease avoidance behaviors, it may in turn increase the frequency of the stuttering moments. This follows a logical pattern because as the individual relinquishes avoidances, the number of speaking opportunities increases. The World Health Organization (WHO, 2001) would therefore not consider the treatment effective because it does not reduce the impairment level (e.g., stuttering frequency). Moreover, Blomgren et al. (2005) stated that any stuttering modification program in its purest form (i.e., without fluency enhancing techniques) will not be effective in reducing an individual’s stuttering or core behaviors. Fluency shaping, on the other hand, focuses on teaching the individual to speak more fluently (Blomgren et al., 2005; Guitar, 1998). The goal of fluency shaping is to work with the speaker’s speech motor control capabilities and apply various approaches to facilitate new speech production patterns (Blomgren et al., 2005). This technique establishes fluent speech in a controlled environment using both positive and negative reinforcement (Guitar & Peters, 1980; Peters & Guitar, 1991; Shapiro, 1999). Fluency is eventually generalized to normal conversational settings through successive approximations (Shapiro, 1999). A drawback of this method is that it does not incorporate the individual’s feelings and reactions to the disorder (Blomgren et al., 2005). Furthermore, Guitar and Peters (1980) stated that by using this method, speech becomes monotonous and artificial as the client strives for fluent speech. Stuttering modification. Stuttering modification may be targeted through Van Riper’s (1972, 1973) exemplar termed MIDVAS: motivation, identification, desensitization, variation, approximation, and stabilization. According to Van Riper, motivation is the first, and most important, phase. During this phase, the SLP becomes a guide and shares positive information about the treatment process with the client. It is essential for both the client and clinician to become comfortable and to share feelings and emotions regarding the disorder. The SLP must stress the fact that being an active participant in treatment is vital to achieve fluency. Following this phase, Van Riper (1973) describes the identification phase, where the individual identifies stuttering moments that are unique to his or her speech. The rationale behind the identification of traits is that once awareness is attained, the habit may be changed. Goals include diminishing denial and identifying stuttering behaviors. The third phase, desensitization, “implies stress” (Shapiro, 1999, p. 197). During this phase, the client’s negative feelings and emotions toward the disorder are addressed. Some techniques include relaxation, pseudostuttering, adaptation, and anxiety reduction by modifying stuttering (Van Riper, 1973). Following desensitization, the SLP may begin modifying the individual’s stuttering (e.g., modifying anticipated behaviors) in the fourth phase, called variation. As the client begins to learn new responses to diminish stuttering moments, he or she enters the approximation phase. During this phase, the SLP continues to modify the client’s speech to attain fluency. Some approximation techniques include cancellation, pullouts, and preparatory sets (Van Riper, 1973). Treatment is reduced during the stabilization phase. As the client gains a positive self-image, he or she begins to self-monitor the stuttering. Treatment may be terminated in this final stage (Van Riper, 1973). Because stuttering modification focuses on desensitization and reducing the individual’s anxiety, it is difficult to obtain outcome measures and quantify the efficacy of the technique (Blomgren et al., 2005). The Successful Stuttering Management Program (SSMP; Breitenfeldt & Lorenz, 1989) is an example of a stuttering modification treatment; there is, however, no evidence of its effectiveness (Blomgren et al., 2005; De Nil & Kroll, 1996; Ham, 1996). The SSMP is a 3-week program that is based on stuttering modification techniques advocated by Van Riper (1973)—a combination of desensitization techniques and avoidance reduction therapy (Sheehan, 1970). Breitenfeldt and Girson (1995) described positive changes in individuals’ attitudes toward stuttering and secondary behaviors following this program. Eichstadt, Watt, and Girson (1998) also reported positive changes; however, no pretreatment baselines were obtained (Blomgren et al., 2005). Stuttering modification: Measuring attitudes and beliefs. In creating a treatment plan for individuals who stutter, it is not sufficient to count the number of disfluencies or the frequency of stuttering moments. Assessing attitudes, emotions, self-esteem, and environmental factors is an essential aspect in preparing treatment goals. Sheehan (1970) stated, “Stuttering is like an iceberg, with only a small part above the waterline and a much bigger part below” (pp. 184–185). Because the overt aspects of stuttering account for only 10% of the problem (Hicks, 2003), it is important to evaluate the attitudes and emotions of the person who stutters, or 90% of the disorder, using the various scales available. Self-measurement, self-monitoring, and self-observations are considered direct measures of behavior (Cone, 1999); however, they may also include many personal biases (Gilovich, 1991). The main purpose of self-measurement is to serve as a therapeutic intervention (Foster, LavertyFinch, Gizzo, & Osantowski, 1999). Individuals who stutter develop belief systems over time that include attitudes about their individual abilities to speak and the effect of situations and listeners on their speech and fluency. Negative emotional reactions and avoidance behaviors are two measurable types of covert characteristics of stuttering. Building a sense of confidence and self-worth is another central aspect in the treatment of stuttering. According to the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE; Rosenberg, 1965), self-esteem is a broad concept that is used to measure a person’s “global” or “unidimensional” self-evaluation (Gray-Little, Williams, & Hancock, 1997). McCarthy and Hoge (1982) stated that the scale has been found to be valid and reliable among students in Grades 7–12. The RSE includes 10 statements that are scored using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0, strongly agree, to 3, strongly disagree. Cooperman, Bloom, and Klein (2007) adopted Sidavi • Fabus: Stuttering Intervention Approaches Downloaded from: https://pubs.asha.org 168.232.62.66 on 02/18/2022, Terms of Use: https://pubs.asha.org/pubs/rights_and_permissions 17 Rosenberg’s scale for children by simplifying the statements and the Likert scale. The Self-Esteem Scale—Modified for Children also contains a 4-point scale; however, 1 represents Yes, I think this is true, and 4 represents No, I never think this is true. Other scales are used to assess children’s attitudes and perceptions toward the disorder, such as the Communication Attitude Test (CAT; Brutten, 1985) and the Communication Attitude Test—Revised (CAT–R; Brutten, 1985). The CAT consists of 35 true and false questions that are used to assess the child’s perception of stuttering. The CAT has been translated into various languages and has been researched in 15 countries (Brutten & Vanryckeghem, 2003, 2007; De Nil & Brutten, 1991; Vanryckeghem & Mukati, 2006). De Nil and Brutten (1991) and Vanryckeghem and Brutten (1992) have found significant test–retest reliability, high correlations, and interitem reliability for the CAT–R (Brutten & Dunham, 1989). There have been high correlations between negative speech-associated attitudes and emotions among children who stutter and those who do not stutter. Moreover, there is a relationship between the negative beliefs about the speech, attitudes, and emotions of children who stutter and the anxiety associated with their communication (Vanryckeghem, Hylebos, Brutten, & Peleman, 2001). It is important, therefore, to determine a child’s attitudes toward his or her disorder at an early age. Vanryckeghem (1995) found that parents do not accurately convey their child’s belief systems. For this reason, there has been extensive research with the KiddyCat (Langevin, 2007), a communication attitude test for preschoolers and kindergartners who stutter (Ambrose & Yairi, 1994; Vanryckeghem & Brutten, 2007; Vanryckeghem, Brutten, & Hernandez, 2005). Researchers found that children who stutter develop negative attitudes toward their speech as early as 3 years of age. A more comprehensive scale, the CALMS Rating Scale for Children Who Stutter (ages 7–15), is based on Healey, Scott Trautman, and Susca’s (2004) multidimensional model of stuttering. The scale addresses five key factors: cognitive, affective, linguistic, motor, and social. Each item on the scale is rated from 1 to 5, with 1 representing normal and no concern and 5 representing severe impairment and extreme concern. By computing the total value of all of the items and dividing it by the number of items scored, a mean score for each component is obtained. The average score is used to create a CALMS profile (Healey, 2007; Healey et al., 2004). Coleman and Yaruss (2004) devised an alternative instrument, the Assessment of the Child’s Experience of Stuttering (ACES), to assess the overall impact of stuttering on the child’s life from the child’s perspective. The ACES was adapted from an adult scale, Overall Assessment of the Speaker’s Experience of Stuttering (OASES; Yaruss & Quesal, 2004), to assess stuttering in children 7 to 18 years of age. The ACES is divided into four sections: general information about stuttering, reactions to stuttering (affective, behavioral, and cognitive), communication in daily situations, and impact of stuttering on quality of life. The instrument evaluates (a) the child’s perception of speech fluency, speech naturalness, and speech therapy techniques; 18 CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN COMMUNICATION SCIENCE AND (b) the child’s affective, behavioral, and cognitive reactions to stuttering; (c) the child’s difficulty in communicating at school, at home, and in social situations; and (d) the impact of stuttering on the child’s overall quality of life (Coleman & Yaruss, 2004). The questionnaire consists of 100 items that can be completed in 15–20 min. After gathering the necessary information, the clinician can create a more individualized treatment plan for the child. Fluency shaping. Aside from working on desensitization of stuttering, increasing the fluency of stuttering may be targeted by implementing two fluency shaping programs, Programmed Conditioning for Fluency (Ryan & Van Kirk, 1971) and Programmed Therapy for Stuttering in Children and Adults (Ryan, 1974). Fluency is established through one of four techniques: gradual increase in length and complexity of utterances (GILCU), delayed auditory feedback (DAF), programmed traditional, and punishment (Shapiro, 1999). GILCU is a 54-step program that directs the client to produce fluent speech (Shapiro, 1999). It begins with single-word responses and is increased to six words. The client’s speech is gradually increased from 5 min of passage reading to monologue speech, ending in conversational speech with normal speaking rates (Ryan & Ryan, 1995). The method has been found to be effective and efficient (Costello, 1980, 1983; Rustin, Ryan, & Ryan, 1987; Ryan & Ryan, 1995; Shine, 1984). Costello (1980) used a more defined GILCU approach called the Extended Length Utterance (ELU) program. The ELU program is similar to the GILCU program; however, instead of beginning with words, it uses syllables. It is completed in 20 steps, beginning with monologue and ending in conversational speech (Costello, 1980). Traditional programs identify an individual’s stuttered words and then shape fluent responses using Van Riper’s techniques, cancellation, pullouts, and preparatory sets (Shapiro, 1999). Punishment, on the other hand, reduces the frequency of stuttering by presenting an aversive condition (Shapiro, 1999). Lidcombe Program The Lidcombe Program is a behavioral parent-directed treatment for stuttering in preschool children that was developed by the Faculty of Health Sciences at The University of Sydney and the Stuttering Unit of the Bankstown Health Service in Sydney, Australia. Using this program, the SLP teaches the parent to deliver treatment to the child and to use a 10-point Likert scale to measure the severity of the child’s stuttering in his or her everyday environment (Onslow, Packman, & Harrison, 2003; Rousseau et al., 2007). There are two stages to the program. In Stage 1, the parent and child meet with the SLP on a weekly basis for the parent to deliver treatment in the child’s environment daily (Onslow et al., 2003; Rousseau et al., 2007). The SLP measures the percentage of syllables that are stuttered (%SS), and the parent monitors the child’s speech using a 10-point scale where 1 represents the absence of stuttering and 10 represents extremely severe stuttering (Rousseau DISORDERS • Volume 37 • 14–26 • Spring 2010 Downloaded from: https://pubs.asha.org 168.232.62.66 on 02/18/2022, Terms of Use: https://pubs.asha.org/pubs/rights_and_permissions et al., 2007). Once the child’s stuttering decreases, Stage 2 (maintenance stage) begins, where the parent and child attend sessions less frequently, and treatment is decreased (Onslow et al., 2003). Kingston, Huber, Onslow, Jones, and Packman (2003), as well as Jones, Onslow, Harrison, and Packman (2000), found that children with more severe stuttering took longer to complete Stage 1; however, those who had been stuttering longer completed Stage 1 faster than those who had been stuttering for a shorter period of time. Based on the authors’ retrospective file audits, the median treatment time was 11 visits. Rousseau et al.’s (2007) findings, however, indicate a median treatment time of 16 visits. The exact cause of the discrepancy is unclear; Rousseau et al. suggested that possible demographic differences may be responsible. Rousseau et al. (2007) investigated the effect of language and phonology as predictors of treatment time using the Lidcombe Program. Knowing the relationship between language and phonology and whether it affects the timing of intervention is important for clinician decision making during the time of assessment (Rousseau et al., 2007). The authors did not find a relationship between phonological development and the time it takes to complete the first stage of the Lidcombe Program. They did, however, find a relationship between language and treatment time; that is, the higher the child’s mean length of utterance, the shorter the treatment time, and the higher the child’s receptive scores on the Clinical Evaluations of Language Fundamentals (Semel, Wiig, & Secord, 2003), the longer the treatment time. Because the Lidcombe Program does not require programmed instructions, nor does it require the child to change his or her manner of speaking, it is currently the first choice for treatment in preschool-age children (Conture & Curlee, 2007). Because of the social anxiety associated with stuttering at the school-age level (Conture & Curlee, 2007), there is a need to investigate the efficacy of the Lidcombe Program for older children (i.e., between 7 and 11 years of age). Rousseau, Packman, and Onslow (2005) began investigating the efficacy of the Lidcombe Program on school-age children. They investigated how well the children responded and how long it took them to respond. There is some data that suggest that the Lidcombe Program may be effective for school-age children (Lincoln, Onslow, Lewis, & Wilson, 1996); however, Conture and Curlee (2007) stated that based on the data from Rousseau et al. (2005), there are compelling reasons to believe that the program may not be suitable for school-age children. Altered Auditory Feedback Altered auditory feedback (AAF) is a term that is used to encompass altering the speech signal electronically so that the speaker perceives his or her voice differently. There are several types of AAF, including DAF, frequently altered feedback (FAF), and masking auditory feedback (MAF). AAF techniques have been found to reduce stuttering by decreasing the child’s rate of speech (Armson & Stuart, 1998; Hargrave et al., 1994; Howell et al., 1999; Van Borsel et al., 2003). Kalinowski, Armson, RolandMieszkowski, Stuart, and Gracco (1993) and Hargrave et al. (1994), however, found that a reduction in speech rate is not necessary for the production of fluent speech using AAF programs. DAF, or prolongation, has been studied extensively to reduce stuttering in adolescence and in adults who stutter (Boberg, 1980; R. J. Ingham & Andrews, 1973; Ryan & Ryan, 1995; Ryan & Van Kirk, 1974; Webster, 1980). DAF occurs when there is a 50–100 ms delay in the arrival of the voice signal to the speaker’s ear. In the early stages of DAF, a long delay was used (250 ms), which produced slow and prolonged speech (Ryan, 1974; Ryan & Ryan, 1995). There are 25 steps to the program. The least amount of time needed to complete the program is 110 min (Ryan, 1974; Ryan & Ryan, 1995; Ryan & Van Kirk, 1974). The aim of the DAF program is to produce slow, paced speech: a total of 40 words or less produced per minute (Ryan & Ryan, 1995). Current research indicates the effectiveness of the treatment with short delays (50 ms). In this manner, the person can continue a fast-paced speech while maintaining fluency (Kalinowski, Stuart, Sark, & Armson, 1996). The goal of DAF is to prolong the speaking rate so the client can produce fluent speech (Ryan & Ryan, 1995; Shapiro, 1999). FAF alters the frequency of the individual’s speech (either up or down) between ¼ to 1 octave, affecting the perceived pitch of the person’s voice (Hargrave et al., 1994; Howell, El-Yaniv, & Powell, 1987). Howell et al. (1987) found that study participants using FAF produced fewer disfluencies than those using DAF. Several studies have reported a decrease in stuttering using 1-, ½-, and ¼-octave increasing or decreasing the frequency of speech (Hargrave et al., 1994; Howell et al., 1987; Kalinowski et al., 1993; Stuart, Kalinowski, Armson, Stenstrom, & Jones, 1996); nonetheless, the most consistent results have been found using the 1-octave increase and decrease (Hargrave et al., 1994). DAF, however, has been consistently reported to be more effective than FAF in reducing stuttering (Stuart, Kalinowski, & Rastatter, 1997; Zimmerman, Kalinowski, Stuart, & Rastatter, 1997). Masking noise delivered via headphones or electronic devices has been used to help control stuttering in everyday situations (Armson & Stuart, 1998). The results regarding the effectiveness of masking studies are inconclusive (R. J. Ingham, Southwood, & Horsborough, 1981). This method, however, is now rarely employed because DAF and FAF have been found to be more effective than masking noise at reducing stuttering (Howell et al., 1987; Kalinowski et al., 1993). Overall, AAF, specifically FAF, has been found to increase speech naturalness and reduce the degree of stuttering in difficult speaking situations (White, Kalinowski, & Armson, 1995). Lincoln et al. (2006) reviewed the literature over the past 10 years to assess the effect of AAF on different speaking situations. The authors concluded that in the laboratory, clinic, or classroom, AAF results in reduced stuttering during oral reading for those who stutter. The studies, however, did not suggest the reduction of stuttering in conversational speech. The authors concluded that the Sidavi • Fabus: Stuttering Intervention Approaches Downloaded from: https://pubs.asha.org 168.232.62.66 on 02/18/2022, Terms of Use: https://pubs.asha.org/pubs/rights_and_permissions 19 true efficacy of the treatment cannot be determined until the effects on conversational speech are examined (Lincoln et al., 2006). Yaruss and Gable (2005) reviewed the use of AAF devices, specifically, the SpeechEasy device. SpeechEasy is a fluency enhancing device for people who stutter who use DAF, FAF, or a combination of the two. Kalinowski, Stuart, and Rastatter invented the device after reviewing the effects of AAF on people who stutter. The device resembles a hearing aid and was designed for monaural use. There are three main models: behind the ear, in the canal, and completely in the canal. There are no published studies regarding the efficacy of the devices, and no studies have been reported regarding the use of the device with children. Only temporary fluency gains have been reported when using the device. Additionally, because the device is placed in one ear, there may be competing signals in the other ear, causing disruptions in communication. Recently, Saltukaroglu and Kalinowski (2005) proposed that AAF may be a promising treatment option for schoolage children. Howell et al. (1999) and Stuart et al. (2004) studied participants between 9 and 12 years of age and found that children did not respond as well as adults to AAF conditions. No conclusions can therefore be made regarding the effects of AAF devices on children. There is no evidence in the literature that suggests the use of AAF in children under the age of 9 years. Lincoln et al. (2006) stated that altered auditory input on children developing speech and language may create further complications. Monterey Fluency Program The Monterey Fluency Program (Ryan & Van Kirk, 1978) is a structured therapy program for preschool- and schoolage children. The program is often combined with the token economy system (Dalton, 1983). This program was designed to provide two alternative schedules for fluency: GILCU and DAF (Bloodstein & Bernstein Ratner, 2008). The GILCU program is based on operant conditioning principles where there is an established structured program for reinforcement of utterances. The DAF program is used with older children and helps the client to read and speak in a slow manner where all the words are prolonged. Fluency Rules Program The Fluency Rules Program (FRP; Runyan & Runyan, 1993, 1999) was designed for preschool- and school-age children. Originally, the program was named “Rules for Good Speech” and consisted of 10 fluency rules. The program was expanded, however, to include three sections: universal rules, primary rules, and secondary rules. It was realized that not all children who stutter need the 10 rules. Universal rules, therefore, are rules that all children who stutter use. These rules include reduce the rate of speech, say each word once, and say it short. Reducing the rate of speech allows children to monitor their speech. Slow speech was reported by SLPs to have a calming effect on children who stutter (Runyan & Runyan, 2007). Using symbolic therapy materials (e.g., turtle or snail) may 20 CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN COMMUNICATION SCIENCE AND assist children in establishing a slow speech rate (Runyan & Runyan, 1986) The second rule, say the word once, reduces the number of repetitions (e.g., whole-word repetition, part-word repetition, single syllable repetition). The third universal rule, say it short, was designed to decrease prolongations (Runyan & Runyan, 2007). If airflow and/or laryngeal difficulties are present, primary rules are enforced. These rules include use speech breathing and “start Mr. voice box running smoothly.” Speech breathing, or speaking on exhaled air, is illustrated to the child (Runyan & Runyan, 2007). In addition, children are taught to begin vocal fold movement smoothly, also referred to as easy onset (Bennett, 2006; Schwartz, 1999; Zebrowski & Kelly, 2002). Lastly, when concomitant behaviors are present, two additional, secondary, rules are implemented: “Touch the speech-helpers lightly” and use only the “speech-helpers” to talk. The “speech-helpers” (e.g., tongue, lips, teeth) are depicted using cartoon characters. Children are taught to “touch the speech-helpers lightly” because if they close the articulators too tight, they will stop speech breathing, and speech production will cease (Runyan & Runyan, 2007). Runyan and Runyan (1985) pilot tested the FRP in a public school on 9 children who stuttered (3–7 years of age) to determine its efficacy in a public school setting in school-age children. The results indicated, as per the Stuttering Severity Instrument—3rd Edition (SSI–3; Riley, 1972), that the frequency of stuttering, as well as the severity of the blocks, decreased. Additionally, the children remained fluent 1–2 years after treatment. Comprehensive Stuttering Program for School-Age Children Attitudinal and emotional aspects of stuttering and overt stuttering are addressed with the Comprehensive Stuttering Program for School-Age Children (CSP-SC; Boberg & Kully, 1985). The CSP targets four main goals: speechrelated goals, attitudinal–emotional goals, self-management goals, and environmental goals. Teaching fluency enhancement skills, addressing attitudes and emotions, and incorporating the family into therapy address the targeted goals (Langevin, Kully, & Ross-Harold, 2007). Speech-related goals are achieved by teaching fluency enhancing skills in various environments with normal rate and prosody, managing residual stuttering, and improving communication skills (Langevin et al., 2007). Fluency enhancing skills include prolongations, easy breathing, gentle starts, smooth blending, light touches, and tension modification. Feelings, attitudes, and emotions are addressed as well. Attitudinal–emotional goals include creating positive attitudes toward communication; comfort with fluency enhancing skills; comfort with stuttering; and ability to manage fear and anxiety, recognize relapse, and improve social skills (Langevin et al., 2007). Self-management goals include problem-solving techniques, self-monitoring, self-evaluation, and the ability to manage the environment. Lastly, environmental goals target parental understanding of the disorder. Environmental goals include the etiology and development of stuttering, how to DISORDERS • Volume 37 • 14–26 • Spring 2010 Downloaded from: https://pubs.asha.org 168.232.62.66 on 02/18/2022, Terms of Use: https://pubs.asha.org/pubs/rights_and_permissions deliver therapy, and how to deal with relapse (Langevin et al., 2007). Regulated Breathing Regulated breathing is designed to help individuals who stutter become aware of their stuttering moments. Using this technique, the SLP teaches the client to interrupt or prevent the occurrence of stuttering by completing responses that involve regulating airflow during speech. The technique includes awareness training, relaxation training, motivational training, and generalization training (Watson & Skinner, 2004). Researchers have shown that regulated breathing is an effective technique for increasing fluency in both children and adults. Reports regarding regulated breathing have indicated a decrease in stuttering without a reduction in speech rate (Andrews & Tanner, 1982; Ladouceur et al., 1982; Woods & Twohig, 2000). Ladouceur et al. (1982), as well as Andrews and Tanner (1982), replicated the study done by Azrin and Nunn (1974) on the treatment of stuttering using regulated breathing training. The authors repeated the study for various reasons, including the various methodological limitations of the study, the lack of a definition of stuttering, and the fact that the measures of stuttering were based solely on self-reported estimates. Furthermore, Andrews and Tanner stated that no other accounts of the efficacy of the treatment method had been published. Self-Modeling Self-modeling has been described in the literature as selfas-a-model (Hosford, 1981) and as self-observation (McCurdy & Shapiro, 1988; Shear & Shapiro, 1993). Selfmodeling includes training an individual using self-exposure of error-free behaviors to promote change (Webber, Packman, & Onslow, 2004). Dowrick (1999) defined selfmodeling as an intervention approach in which the individual views a 2- to 4-min edited videotape of him- or herself engaging in exemplary behaviors. Through self-modeling, an individual learns the target behavior by observing himor herself engaging in positive behaviors from prerecorded and pre-edited videotapes (Murphy, 2001). According to Dowrick (1999), individuals can learn by observing their own behaviors. The efficacy of selfmodeling has been reported to be successful: Meharg and Woltersdorf (1990) reviewed 27 articles, all of which indicated positive outcomes using the treatment method. Furthermore, Bray and Kehle (1996) found a reduction in stuttering and maintenance of treatment gains using self-modeling for the 3 students involved in their study. Bray and Kehle (2001) examined the long-term effects of self-modeling over 2 and 4 years of treatment. The authors found that the study participants’ fluency was maintained for the two periods under investigation. Webber et al. (2004) investigated whether their aims could be attributed to the watching of selfmodeling videotapes. The authors found that self-modeling can reduce stuttering; however, they suggest incorporating the technique into other treatment methods. There are several limitations to this intervention approach. First, it may be difficult to edit an acceptable behavior(s) into or out of the videotape to indicate the target behavior(s). In addition, the actual editing of the videotape is difficult, and the equipment may be expensive (Clark & Kehle, 1992). Second, the child’s interpretation of the behavior may not be in accordance with the clinician’s interpretation of the behavior (Clark & Kehle, 1992). Last, the client’s age and cognitive capacity need to be taken into account because the videotapes represent a behavior that will appear in the future. The child may or may not be able to self-reflect on his or her own abilities (Clark & Kehle, 1992). Synergistic Stuttering Therapy Bloom and Cooperman (1999) developed the Synergistic Model of Intervention with children who stutter. This model accounts for the integration of the physiological or speechlanguage factors (e.g., respiration, voice, articulation, and hearing), attitudes and feeling components, and communication environment (e.g., social and pragmatic influences of communication and family influences). The “treatment principles of the synergistic approach are based on the same principles that relate to normal speech production” (Bloom & Cooperman, 1999, p. 117). Bloom and Cooperman stressed the importance of teaching the mechanics of normal speech production so that clients could learn about the general processes of respiration, phonation, and articulation using visual devices. They then use various activities to help the client increase his or her awareness about the stuttering moment. Afterward, the client is taught the respiratory, phonatory, and articulatory targets of normal speech production. The treatment principles for the speech-language factors encompass using the target skills during four phases: identification phase, modification and establishment phase, stabilization phase, and transfer and maintenance phase. Bloom and Cooperman indicated that feelings and attitudes encompass three main areas: self-esteem, locus of control, and assertiveness. The last main domain is environmental aspect of the stuttering. Implications for the Treatment of Preschool Children Who Stutter For children younger than 6 years, response-contingent approaches (e.g., Martin, Kuhl, & Haroldson, 1972) to treating stuttering were most effective (Bothe et al., 2006). Response-contingency approaches may be delivered immediately after a stuttering moment or as part of a structural performance-contingent maintenance program (R. J. Ingham, 1980). Martin et al. (1972) achieved near zero stuttering in the home by using response contingencies in therapy: The authors shut the light on the puppet stage for 10 s contingent on stuttering for two preschool boys. Reed and Godden (1977) provided the verbal contingency “slow down” and found a dramatic decrease in the percentage of words stuttered. Onslow, Costa, and Rue (1990) found that verbal contingencies provided by parents reduced the frequency of stuttering as well. Sidavi • Fabus: Stuttering Intervention Approaches Downloaded from: https://pubs.asha.org 168.232.62.66 on 02/18/2022, Terms of Use: https://pubs.asha.org/pubs/rights_and_permissions 21 According to Bothe et al.’s (2006) systematic treatment review of stuttering treatment, the Lidcombe Program (Onslow et al., 2003) is the best response-contingent approach for preschool children who stutter. Lincoln and Onslow (1997) provided follow-up treatment for children 2 to 7 years posttreatment, with results indicating a mean stuttering below 1%SS. In addition, children’s psychosocial levels increased after Lidcombe treatment (Woods, Shearsby, Onslow, & Burnham, 2002). One important impediment in treating preschool children who stutter is the spontaneous, or natural, recovery (Bothe et al., 2006). R. J. Ingham (1993) and R. J. Ingham and Cordes (1999) estimate that 30% to 50% of preschool children recover without treatment. The solution is to have continuous assessments over time (J. C. Ingham & Riley, 1998). Bernstein Ratner, N. (1997). Leaving Las Vegas: Clinical offs and individual outcomes. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 15, 296–302. Bernstein Ratner, N., & Tetnowski, J. (2006). Stuttering treatment in the new millennium: Changes in the traditional parameters of clinical focus. In N. Bernstein Ratner & J. Tetnowski (Eds.), Current issues in stuttering research and practice (pp. 1–16). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Blomgren, M., Roy, N., Callister, T., & Merrill, R. M. (2005). Intensive stuttering modification therapy: A multidimensional assessment of treatment outcomes. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 48, 509–528. Bloodstein, O., & Bernstein Ratner, N. (2008). A handbook on stuttering. Clifton Park, NY: Thomson Delmar Learning. Bloom, C., & Cooperman, D. (1999). Synergistic stuttering therapy: A holistic approach. Boston, MA: Butterworth Heineman. Boberg, E. (1980). Intensive adult therapy program. Seminars in Speech, Language, and Hearing, 1, 365–374. CONCLUSION Boberg, E., & Kully, D. (1985). The comprehensive stuttering program. San Diego, CA: College-Hill Press. In developing a treatment program for children who stutter, one must consider many variables and decide on an appropriate outcome measure: The measures should include both overt and covert behaviors. Bennet (2006) has written about the ABCs of stuttering, which include affective, behavioral, and cognitive components of stuttering. A treatment program should integrate all of these aspects of the disorder. For these reasons, the clinician’s task consists of choosing a well-developed, evidence-based assessment instrument that meets the client’s needs and goals. Bothe, A. K., Davidow, J. H., Bramlett, R. E., Franic, D. M., & Ingham, R. J. (2006). Pharmacological approaches to stuttering treatment: Reply to Meline and Harn. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17, 98–101. ACKNOWLEDGMENT Thank you to Ciara Leydon for reviewing this manuscript before submission. Bradberry, A. (1995). The role of support groups and stuttering therapy. Seminars in Speech and Language, 18, 391–399. Bray, M. A., & Kehle, T. J. (1996). Self-modeling as an intervention for stuttering. School Psychology Review, 25, 358–369. Bray, M. A., & Kehle, T. J. (2001). Long-term follow-up of self modeling as an intervention for stuttering. School Psychology Review, 30, 135–141. Breitenfeldt, D. H., & Girson, J. (1995). Efficacy of the Successful Stuttering Management Program workshops in the United States of America and South Africa. In C. W. Starkweather & H. F. M. Peters (Eds.), Proceedings of the First World Congress on Fluency Disorders (pp. 429–431). Nijmegen, The Netherlands: Nijmegen University Press. Breitenfeldt, D. H., & Lorenz, D. R. (1989). Successful stuttering management program for adolescent and adult stutterers (1st ed.). Cheney, WA: Eastern Washington University. REFERENCES Adams, M. R. (1984). The differential assessment and direct treatment of stuttering. In J. Costello (Ed.), Speech disorders in children (pp. 261–290). San Diego, CA: College Hill Press. Brutten, G. (1985). Communication Attitude Test. Unpublished manuscript, Carbondale University, Southern lllinois. Ambrose, N., & Yairi, E. (1994). The development of awareness of stuttering in preschool children. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 19, 229–245. Brutten, G., & Dunham, S. (1989). The Communication Attitude Test: A normative study of grade school children. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 14, 371–377. Andrews, G., & Tanner, S. (1982). Stuttering treatment: An attempt to replicate the regulated breathing method. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 47, 138–140. Brutten, G., & Vanryckeghem, M. (2003). Behavior Assessment Battery: A multi-dimensional and evidence-based approach to diagnostic and therapeutic decision making for children who stutter. Destelbergen, Belgium: Stichting Integratie Gehandicapten & Acco Publishers. Armson, J., & Stuart, A. (1998). Effect of extended exposure to frequency altered feedback on stuttering during reading and monologue. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 41, 479–490. Brutten, G., & Vanryckeghem, M. (2007). Behavior Assessment Battery for Children Who Stutter. San Diego, CA: Plural. Attanasio, J. S. (1994). Inferential statistics and treatment efficacy studies in communication disorders. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 37, 755–759. Clark, E., & Kehle, T. J. (1992). Evaluation of the parameters of self-modeling interventions. School Psychology Review, 21, 246–255. Azrin, N. H., & Nunn, R. G. (1974). A rapid method of eliminating stuttering by a regulated breathing approach. Behavior Research and Therapy, 12, 279–286. Coleman, C. E., & Yaruss, J. S. (Eds). (2004). ACES: New stuttering assessment tool. Stuttering Center of Western Pennsylvania, 2(6), 1. Bennett, E. M. (2006). Working with people who stutter: A lifespan approach. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. Coleman, C. E., Yaruss, J. S., Butkiewicz, D., & Roccon, R. (2005). Research and training update in fluency disorders. 22 CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN COMMUNICATION SCIENCE AND DISORDERS • Volume 37 • 14–26 • Spring 2010 Downloaded from: https://pubs.asha.org 168.232.62.66 on 02/18/2022, Terms of Use: https://pubs.asha.org/pubs/rights_and_permissions Retrieved from www.stutteringcenter.org/PDF/ 2004%20PSHA%20-%20TrainingUpdate.ppt. Cone, J. D. (1999). Introduction to the special section on selfmonitoring: A major assessment method in clinical psychology. Psychological Assessment, 11, 411–414. Conture, E. (Ed.). (2002). Stuttering and your child: Questions and answers. Memphis, TN: Stuttering Foundation of America. Conture, E. G. (1997). Stuttering and your child: A videotape for parents [Videotape]. Memphis, TN: Stuttering Foundation of America. Conture, E. G. (2001). Stuttering: Its nature, diagnosis and treatment. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Conture, E. G., & Curlee, R. F. (2007). Stuttering and related disorders of fluency (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Thieme Medical. Conture, E. G., & Guitar, B. E. (1993). Evaluating efficacy of treatment of stuttering: School-age children. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 18, 253–287. Cooper, E. B., & Cooper, C. S. (1985). Clinicians’ attitudes toward stuttering: A decade of change (1973–1983). Journal of Fluency Disorders, 10, 19–33. Cooper, E. B., & Rustin, L. (1985). Clinician attitudes toward stuttering in the United States and Great Britain: A cross-cultural study. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 10, 1–17. Cooperman, D., Bloom, C., & Klein, J. (2007). Modified Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Costello, J. (1980). Operant conditioning and the treatment of stuttering. Seminars in Speech, Language, and Hearing, 1, 311–326. Costello, J. (1983). Current behavioral treatments for children. In D. Prins & R. Ingham (Eds.), Treatment of stuttering in early childhood (pp. 69–112). San Diego, CA: College Hill Press. Crowe, T. A. (Eds.). (1997). Applications of counseling in speechlanguage pathology and audiology. Philadelphia, PA: Williams & Wilkins. Curlee, R. F., & Perkins, W. H. (Eds.). (1984). Nature and treatment of stuttering: New directions. San Diego, CA: College Hill. Curlee, R., & Yairi, E. (1997). Early intervention with early childhood stuttering: A critical examination of the data. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 6(2), 8–18. Dalton, P. (Ed.). (1983). Approaches to the treatment of stuttering. New York, NY: Routledge. De Nil, L., & Brutten, G. (1991). Speech-associated attitudes of stuttering and nonstuttering children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 24, 60–66. De Nil, L. F., & Kroll, R. M. (1996). Therapy reviews: Successful Stuttering Management Program (SSMP). Journal of Fluency Disorders, 21, 61–64. DiLollo, A., & Manning, W. H. (2007). Counseling children who stutter and their parents. In E. G. Conture & R. F. Curlee (Eds.), Stuttering and related disorders of fluency (3rd ed., pp. 115–130). New York, NY: Thieme. Dowrick, P. W. (1999). A review of self-modeling and related interventions. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 8, 23–39. Eichstadt, A., Watt, N., & Girson, J. (1998). Evaluation of the efficacy of a stutter modification program with particular reference to two new measures of secondary behaviors and control of stuttering. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 23, 231–246. Finn, P. (1996). Establishing the validity of recovery from stuttering without formal treatment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 39, 1171–1181. Foster, S. L., Laverty-Finch, C., Gizzo, D. P., & Osantowski, J. (1999). Practical issues in self-observation. Psychological Assessment, 11, 426–438. Gilovich, T. (1991). How we know what isn’t so: The fallibility of human reason in everyday life. New York, NY: The Free Press. Gottwald, S. R., & Starkweather, C. W. (1995). Fluency intervention for preschoolers and their families in the public schools. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 2, 117–126. Gray-Little, B., Williams, V., & Hancock, T. (1997). An item response theory analysis of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Personality and Society Psychology Bulletin, 23(5), 443–451. Gregory, H. H. (1979). Controversial issues: Statement and review of the literature. In H. H. Gregory (Ed.), Controversies about stuttering therapy (pp. 1–62). Baltimore, MD: University Park Press. Guitar, B. (1998). Stuttering: An integrated approach to its nature and treatment (2nd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins. Guitar, B., & Peters, T. J. (1980). Stuttering: An integration of contemporary therapies [Publication 16]. Memphis, TN: Stuttering Foundation of American. Ham, R. E. (1996). Therapy review: Successful Stuttering Management Program (SSMP). Journal of Fluency Disorders, 21, 64–67. Hargraves, S., Kalinowski, J., Stuart, A., Armson, J., & Jones, K. (1994). Effects of frequency altered feedback on stuttering frequency at normal and fast speech rates. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 37, 1313–1319. Healey, C. E. (2007). A multidimensional approach to the assessment of children who stutter. Perspectives on Fluency and Fluency Disorders, 17(3), 6–9. Healey, C. E., Scott Trautman, L., & Susca, M. (2004). Clinical applications of a multidimensional approach for the assessment and treatment of stuttering. Contemporary Issues in Communication Science and Disorders, 31, 40–48. Hill, D. (2003). Differential treatment of stuttering in the early stages of development. In H. Gregory (Ed.), Stuttering therapy: Rationale and procedures (pp. 142–185). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Hosford, R. E. (1981). Self-as-a-model: A cognitive, social-learning technique. Counseling Psychology, 9, 45–62. Howell, P., El-Yaniv, N., & Powell, D. J. (1987). Factors affecting fluency in stutterers when speaking under altered auditory feedback. In H. F. M. Peters & W. Hulstijn (Eds.), Speech motor dynamics in stuttering (pp. 361–369). New York, NY: SpringerVerlag. Howell, P., Sackin, S., & Williams, R. (1999). Differential effects of frequency-shifted feedback between child and adult stutterers. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 24, 127–136. Ingham, J. C., & Riley, G. (1998). Guidelines for documentation of treatment efficacy for young children who stutter. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 41, 753–770. Ingham, R. J. (1980). Modification of maintenance and generalization during stuttering treatment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 23, 732–745. Ingham, R. J. (1993). Spontaneous remission of stuttering: When will the emperor realize he has no clothes on? In D. Prins & R. J. Ingham (Eds.), Treatment of stuttering in early childhood: Methods and issues (pp. 113–140). San Diego, CA: College Hill Press. Ingham, R. J., & Andrews, G. (1973). Behavior therapy and stuttering. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 38, 405–441. Sidavi • Fabus: Stuttering Intervention Approaches Downloaded from: https://pubs.asha.org 168.232.62.66 on 02/18/2022, Terms of Use: https://pubs.asha.org/pubs/rights_and_permissions 23 Ingham, R. J., & Cordes, A. K. (1998). Treatment decisions for young children who stutter: Further concerns and complexities. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 7, 10–19. Luterman, D. M. (2001). Counseling persons with communication disorders and their families (4th ed.). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. Manning, W. (1996). Clinical decision-making in the diagnosis and treatment of fluency disorders. Albany, NY: Delmar. Ingham, R. J., & Cordes, A. K. (1999). On watching a discipline shoot itself in the foot: Some observations on current trends in stuttering treatment. In N. B. Ratner & E. C. Healey (Eds.), Stuttering research and practice: Bridging the gap (pp. 221–230). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Manning, W. H. (1999). Creating your own map for change. Retrieved from http://www..mnsu.edu/dept/comdis/isad2/papers/ manning2.html. Ingham, R. J., Southwood, H., & Horsborough, G. (1981). Some effects of the Edinburgh masker on stuttering during oral reading and spontaneous speech. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 6, 135–154. Jones, M., Onslow, M., Harrison, E., & Packman, A. (2000). Treating stuttering in young children: Predicting treatment time in the Lidcombe Program. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 43, 1440–1450. Kelly, E. M. (1995). Parents as partners: Including mothers and fathers in the treatment of children who stutter. Journal of Communication Disorders, 28, 93–106. Kingston, M., Huber, A., Onslow, M., Jones, M., & Packman, A. (2003). Predicting treatment time with the Lidcombe Program: Replication and meta-analysis. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 38, 165–177. Krall, T. (2001). The International Stuttering Association: Objectives activities outlook: Our dreams for self-help and therapy. In H. -G. Bosshardt, J. S. Yaruss, & H. F. M. Peters (Eds.), Fluency disorders: Theory, research, treatment, and self-help. Proceedings of the Third World Congress on Fluency Disorders (pp. 30–40). Nijmegen, The Netherlands: Nijmegen University Press. Kubler-Ross, E. (1969). On death and dying. New York, NY: Macmillan. Ladouceur, R., Cote, C., Leblond, G., & Bouchard, L. (1982). Evaluation of regulated breathing method and awareness training in the treatment of stuttering. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 47, 422–426. Langevin, M. (2007). Review of the KiddyCat: Communication attitude test for preschool and kindergarten children who stutter. Canadian Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, 31, 194–195. Lincoln, M. A., & Onslow, M. (1997). Long-term outcome of early intervention for stuttering. American Journal of SpeechLanguage Pathology, 61(1), 51–58. Lincoln, M. A., Onslow, M., Lewis, C., & Wilson, L. (1996). A clinical trial of an operant treatment for school-age children who stutter. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 5, 73–85. 24 CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN COMMUNICATION SCIENCE AND Meharg, S. S., & Woltersdorf, M. A. (1990). Therapeutic use of videotape self-modeling: A review. Advances in Behavior Research and Therapy, 12, 85–99. Meline, T., & Schmidt, J. F. (1997). Case studies for evaluating statistical significance in group designs. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 6, 33–41. Kalinowski, J., Stuart, A., Sark, A., & Armson, J. (1996). Stuttering amelioration at various auditory feedback delays and speech rates. European Journal of Disorders and Communication, 31, 259–269. Lawrence, M., & Barclay, D. (1998). Stuttering: A brief review. American Family Physician, 57(9), 2157–2158. McCarthy, J. D., & Hoge, D. R. (1982). Analysis of age effects in longitudinal studies of adolescent self-esteem. Developmental Psychology, 18(3), 372–379. McCurdy, B. L., & Shapiro, E. S. (1988). Self observation and the reduction of inappropriate classroom behavior. Journal of School Psychology, 26, 371–378. Kalinowski, J., Armson, J., Roland-Mieszkowski, M., Stuart, A., & Gracco, V. (1993). Effects of alterations in auditory feedback and speech rate on stuttering frequency. Language and Speech, 36, 1–16. Langevin, M., Kully, D. A., & Ross-Harold, B. (2007). The comprehensive stuttering program for school-age children with strategies for managing teasing and bullying. In E. G. Conture & R. F. Curlee (Eds.), Stuttering and related disorders of fluency (3rd ed., pp. 131–149). New York, NY: Thieme. Martin, R. R., Kuhl, P., & Haroldson, S. K. (1972). An experimental treatment with two preschool stuttering children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 15, 743–752. Muma, J. R. (1993). The need for replication. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 36, 927–930. Murphy, J. J. (2001). Video self-modeling. Retrieved from http:// faculty.uca.edu/~jmurphy/SFPS/Innovations/Self_Modeling.htm. Onslow, M. (1992). Choosing a treatment procedure for early stuttering: Issues and future directions. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 35, 983–993. Onslow, M. (1995). Behavioral management of stuttering. San Diego, CA: Singular. Onslow, M. (1997). Seminar: The Lidcombe Program of early stuttering intervention: Overview. New York, NY: Columbia University. Onslow, M., Andrews, C., & Lincoln, M. (1994). A control/experimental trial of an operant treatment for stuttering. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 37, 1244–1259. Onslow, M., Costa, L., & Rue, S. (1990). Direct early intervention with stuttering: Some preliminary data. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 55, 405–416. Onslow, M., Packman, A., & Harrison E. (2003). Lidcombe Program of early stuttering intervention: A clinician’s guide. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. Onslow, M., Packman, A., Stocker, C., van Doom, J., & Siegel, G. (1997). Control of children’s stuttering with response-contingent time-out: Behavioral, perceptual, and acoustic data. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 40, 121–133. Payne, P. A. G. (2002). How in the world did you ever get interested in stuttering? Newsletter of the ASHA Special Interest Division 14, 8(2), 5–8. Packman, A., Onslow, M., & Attanasio, J. S. (2003). The timing of early intervention with the Lidcombe Program. In M. Onslow, A. Packman, & E. Harrison (Eds.), The Lidcombe Program of early stuttering intervention: A clinician’s guide (pp. 41–55). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. Peters, T. J., & Guitar, B. (1991). Stuttering: An integrated approach to its nature and treatment. Baltimore, MD: William & Wilkins. Prins, D., & Ingham, R. J. (1983). Issues and perspectives. In D. Prins & R. J. Ingham (Eds.), Treatment of stuttering in early DISORDERS • Volume 37 • 14–26 • Spring 2010 Downloaded from: https://pubs.asha.org 168.232.62.66 on 02/18/2022, Terms of Use: https://pubs.asha.org/pubs/rights_and_permissions childhood: Methods and issues (pp. 141–145). San Diego, CA: College Hill Press. Ramig, P. (1993). The impact of self-help groups on persons who stutter: A call for research. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 18, 351–361. Reed, C. G., & Godden, A. L. (1977). An experimental treatment using verbal punishment with two preschool stutterers. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 2, 225–233. Richels, C. G., & Conture, E. G. (2007). An indirect treatment approach for early intervention for childhood stuttering. In E. G. Conture & R. F. Curlee (Eds.), Stuttering and related disorders of fluency (3rd ed., pp. 77–99). New York, NY: Thieme. Riley, G. D. (1972). A stuttering severity instrument for children and adults. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 37, 314–322. Rollin, W. J. (2000). Counseling individuals with communication disorders: Psychodynamic and family aspects (2nd ed). Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann. Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Rousseau, I., Packman, A., & Onslow, M. (2005, Summer). The Lidcombe Program with school-age children: A phase I trial. Paper presented at the 7th Oxford Dysfluency Conference, Oxford, UK. Rousseau, I., Packman, A., Onslow, M., Harrison, E., & Jones, M. (2007). An investigation of language and phonological development and the responsiveness of preschool age children to the Lidcombe Program. Journal of Communication Disorders, 40, 382–397. Runyan, C., & Runyan, S. (1993). Therapy for school-age stutterers: An update on the fluency rules program. In R. Curlee (Ed.), Stuttering and related disorders of fluency (3rd ed., pp. 101–114). New York, NY: Thieme Medical. Runyan, C. M., & Runyan, S. E. (1986). A fluency rules therapy program for young children in the public school. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 17, 276–284. Runyan, C. M., & Runyan, S. E. (1999). Therapy for school-age stutterers: An update on the fluency rules program. In R. Curlee (Ed.), Stuttering and related disorders of fluency (3rd ed., pp. 110–123). New York, NY: Thieme Medical. Runyan, C. M., & Runyan, S. E. (2007). The Fluency Rules Program for school-age children who stutter. In E. G. Conture & R. F. Curlee (Eds.), Stuttering and related disorders of fluency (3rd ed., pp. 100–114). New York, NY: Thieme. Rustin, l., Ryan, B., & Ryan, B. (1987). Use of Monterey programmed stuttering therapy in Great Britain. British Journal of Disorders of Communication, 22, 151–162. Ryan, B. (1974). Programmed therapy for stuttering in children and adults. Springfield, IL: Thomas. Ryan, B., & Ryan B. V. K. (1983). Programmed stuttering therapy for children: Comparison of four establishment programs. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 8, 291–321. Ryan, B. P., & Ryan, B. V. K. (1995). Programmed stuttering treatment for children: Comparison of two establishment programs through transfer, maintenance, and follow-up. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 38, 61–75. Ryan, B., & Van Kirk, B. (1971). Programmed conditioning for fluency. Monterey, CA: Behavioral Sciences Institute. Ryan, B., & Van Kirk, B. (1974). The establishment, transfer, and maintenance of fluent speech in 50 stutterers using delayed auditory feedback and operant procedures. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 39, 3–10. Ryan, B., & Van Kirk, B. (1978). Monterey Fluency Program. Monterey, CA: Behavioral Sciences Institute. Saltukaroglu, T., & Kalinowski, J. (2005). How effective is therapy for childhood stuttering? Dissecting and reinterpreting the evidence in light of spontaneous recovery rates. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 40, 359–374. Schwartz, H. D. (1999). A primer for stuttering therapy. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Semel, E., Wiig, E. H., & Secord, W. S. (2003). Clinical Evaluations of Language Fundamentals—4th Edition. Toronto, Canada: The Psychological Corporation. Shames, G. H. (2007). Counseling the communicatively disabled and their families. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Shapiro, D. A. (1999). Stuttering intervention: A collaborative journey to fluency freedom. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. Shear, S. M., & Shapiro, E. S. (1993). Effect of using self-recording and self-observation in reducing disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 31, 519–534. Sheehan, J. G. (1970). Stuttering: Research and therapy. New York, NY: Harper & Row. Shine, R. E. (1984). Direct management of the beginning stutterer. In W. H. Perkins (Ed.), Stuttering disorders (pp. 57–75). New York, NY: Thieme-Stratton. Siegel, G. M. (1990). Concluding remarks. In L. B. Olswang, C. K. Thompson, S. S. Warren, & N. J. Mingetti (Eds.), Treatment efficacy research in communication disorders (pp. 151–176). Rockville, MD: American Speech-Language-Hearing Foundation. Starkweather, C. W., Gottwald, S. R., & Halfond, M. H. (1990). Stuttering prevention: A clinical method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Stuart, A., Kalinowski, J., Armson, J., Stenstrom, R., & Jones, K. (1996). Fluency effect of frequency alterations of plus/minus one-half and one-quarter octave shifts in auditory feedback of people who stutter. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 39, 396–401. Stuart, A., Kalinowski, J., & Rastatter, M. P. (1997). Effect of monaural and binaural altered auditory feedback on stuttering frequency. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 101, 3806–3809. Van Borsel, J., Reunes, G., & Van den Bergh, N. (2003). Delayed auditory feedback in the treatment of stuttering: Clients as consumers. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 38, 119–129. Van Riper, C. (1972). Speech correction: Principles and methods (5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Van Riper, C. (1973). The treatment of stuttering. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Vanryckeghem, M. (1995). The Communication Attitude Test: A concordancy investigation of stuttering and nonstuttering children and their parents. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 20, 191–203. Vanryckeghem, M., & Brutten, G. (1992). The Communication Attitude Test: A test–retest reliability investigation. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 17, 77–90. Vanryckeghem, M., & Brutten, G. (2007). The KiddyCat: A speech-associated attitude test for preschoolers and kindergartners. San Diego, CA: Plural. Sidavi • Fabus: Stuttering Intervention Approaches Downloaded from: https://pubs.asha.org 168.232.62.66 on 02/18/2022, Terms of Use: https://pubs.asha.org/pubs/rights_and_permissions 25 Vanryckeghem, M., Brutten, G., & Hernandez, L. (2005). The KiddyCat: A normative investigation of stuttering and nonstuttering preschoolers’ speech-associated attitude. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 30, 307–318. Yaruss, J. S., Coleman, C., & Hammer, D. (2006). Treating preschool children who stutter: Description and preliminary evaluation of a family-focused treatment approach. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 37, 118–136. Vanryckeghem, M., Hylebos, C., Brutten, G., & Peleman, M. (2001). The relationship between communication attitude and emotion of children who stutter. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 26, 1–15. Yaruss, J. S., & Gable, R. (2005). The National Stuttering Association’s position on the SpeechEasy and other assistive devices. Retrieved from http://www.nsastutter.org/material/index. php?matid=328. Vanryckeghem, M., & Mukati, S. (2006). The Behavior Assessment Battery: A preliminary study of nonstuttering Pakistani grade-school children. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 41, 583–589. Yaruss, J. S., & Quesal, R. W. (2004). Overall Assessment of the Speaker’s Experience of Stuttering. In A. Packman, A. Meltzer, & H. F. M. Peters (Eds.), Theory, research, and therapy in fluency disorders (pp. 237–240). Nijmegen, The Netherlands: Nijmegen University Press. Walton, P., & Wallace, M. (1998). Fun with fluency: Direct therapy with the young child. Bisbee, AZ: Imagineart. Yaruss, J. S., Quesal, R. W., & Murphy, B. (2002). National Stuttering Association members’ opinions about stuttering treatment. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 27, 227–242. Watson, T. S., & Skinner, C. H. (Eds.). (2004). Encyclopedia of school psychology. New York, NY: Plenum. Webber, M., Packman, A., & Onslow, M. (2004). Effects of selfmodelling on stuttering. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 39(4), 509–522. Webster, R. L. (1980). Evolution of a target-based behavioral therapy for stuttering. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 5, 303–320. White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. New York, NY: Norton & Company. White, C. Kalinowski, J., & Armson, J. (1995, December). Clinician’s naturalness ratings of stutterers’ speech under altered auditory feedback. Poster session presented at the annual meeting of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Orlando, FL. Woods, D. W., & Twohig, M. P. (2000). Treatment of stuttering with regulated breathing: Strengths, limitations, and future directions. Behavior Therapy, 31, 547–558. Woods, S., Shearsby, J., Onslow, M., & Burnham, D. (2002). Psychological impact of the Lidcombe Program of early stuttering intervention. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 37, 31–40. Zebrowski, P. M. (1997). Assisting young children who stutter and their families: Defining the role of the speech-language pathologist. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 6(2), 19–28. Zebrowski, P. M., & Kelly, E. M. (2002). Manual of stuttering intervention. New York, NY: Singular. Zebrowski, P. M., Weiss, A., Savelkoul, E., & Hammer, C. (1996). The effect of maternal rate reduction on the stuttering speech rates and linguistic productions of children who stutter: Evidence from individual dyads. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 10, 189–206. Zimmerman, S., Kalinowski, J., Stuart, A., & Rastatter, M. (1997). Effect of altered auditory feedback on people who stutter during scripted telephone conversations. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 40, 1130–1134. World Health Organization. (2001). International classification of functioning, disability, and health: ICF. Geneva, Switzerland: Author. Yairi, E., & Ambrose, N. G. (1999). Early childhood stuttering I: Persistency and recovery rates. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 42, 1097–1112. Yaruss, J. S., Quesal, R. W., Reeves, L., Molt, L., Kluetz, B., Caruso, A. J., … McClure, J. A. (2002). Speech therapy and support group experiences of people who participate in the National Stuttering Association. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 27, 115–135. Contact author: Aimee Sidavi, Department of Speech Communication Arts and Sciences, Brooklyn College, Brooklyn, NY. E-mail: ASidavi@gmail.com. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. 26 CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN COMMUNICATION SCIENCE AND DISORDERS • Volume 37 • 14–26 • Spring 2010 Downloaded from: https://pubs.asha.org 168.232.62.66 on 02/18/2022, Terms of Use: https://pubs.asha.org/pubs/rights_and_permissions