State and Politics in India

Digi tized by

Google

Original frcm

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Themes in Politics Series

GENERAL ED._ITORS

Rlljeev Bharg ava

Partha Chatterjee

The Themes in Politics series aims to bring together essays on import­

ant issues in Indian political science and politics - contemporary

political theory, Indian social and political thought, and foreign policy,

among others. Each volume in the series will bring together the most

significant articles and debates on each issue, and will contain a sub­

stantive introduction and an annotated bibliography.

Digiti zed by

Google

Ori ginal from

---IU:1..i�, l�OF MJCHlGAN.

,...

--

State

and

Politics

in

India

k

Edited by

Partha Chatterjee

DELID

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

CALCUTTA CHENNAI MUMBAI

1998

Dl gl tlzeo by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

.

Oxford Univ:::,sity Press, Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP

J 'J j Oxford

New York

Athens Aue/eland Bangkok Calcutta

·5 /]-1 2 Florence

Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi

Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi

/ <J CJ

8

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne J,,. -.:ico City

Mumbai Nairobi Paris Singapore

Taipei Tokyo Toronto

and associates in

Berlin Ibadan

©Oxford University Press 1997

First Published 1997

Oxford India Paperbacks /998

ISBN O /9 564765 3

Typeset by Resodyn, New Delhi 110070

PrinJed in India at Pauls Press, New Delhi 110020

and published by Manzar Khan, Oxford University Press

YMCA Library Building, Jai Singh Road, New Delhi I JO 00/

Digiti zed by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

0

_a-5.

.S2 4

� �,47

�v--',:l c,.

=t/�/O t>

'

Note from the General Editors

T

eaching of politics in India has long suffered because of the

systematic unavailability of readers with the best contem­

porary work on the subject. The most significant writing in Indian

politics and Indian political thought is scattered in periodicals;

much of the recent work in contemporary political theory is to be

found in inaccessible international journals or in collections that

reflect more the current temper of Western universities than the

need of Indian politics and society.

The main objective of this series is to remove this lacuna. 'The

series also attempts to cover as comprehensively and usefully as

possible the main themes of contemporary research and public

debate on politics, to include selections from the writings of lead­

ing specialists in each field, and to reflect the diversity of research

methods, ideological concerns and intellecrual styles that charac­

terize the discipline of political science today.

We plan to begin with three general volumes, one each in

contemponry political theory, Indian politics and Indian political

thought. A general volume on international politics and specific

volumes ofreadings on particular areas within each of these fields

will follow.

RIJEEV BHAR.GAVA

PARTIIA C!-lATfEIUEE

Dig1t1zeo by

Google

Origi�al rrom

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Digiti zed by

Google

Onginal from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Preface

'"T'iiis volume has been planned to provide a general introduc­

.l tion to th e study of politics in contemporary India. Given

the limited number of essays that could be fitted into a single

volume, several importmt topics and writings have had to be left

out. Besides, a few other essays I would have liked to include could.

not be reprinted here because of difficulties with getting permis­

sion from the original publishers. However, I am somewhat reas­

sured because several other volumes in this series will take up the

subject of Indian politics in greater thematic detail; the essays that

have been left out here will doubtless appear in some of those

volumes:

This volume is primarily addressed to advanced undergraduate

and postgraduate students of political science in South Asian uni­

versities. However, given the interest in the subject among many

other kinds of readers, it may be of use to a wider readership. I

have attempted as far as practicable to keep the discussion up-to­

date.

Apart from my consultations with Rajeev Bhargava, my co­

editor in this series, I have g1eatly benefited from the help given

by my colleagues at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences,

Calcutta, in particular Dwaipayan Bhattacharya, Pradip Bose,

Vivek Dhareshwar and Anjan Ghosh. I must especially thank the

members of the staff of the CSSSC library and reprography

sections for their unstinting support without which I could not

have compiled this volume in the time available to me. Finally,

I thank Oxford University Press for its enthusiasm and efficiency

in handling the planning and production of this volume.

Calcutta

P.C.

September 1996

Dlgltlzedby

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

..

Acknowledgements

"T"'he publishers wish to thank the following for granting permis1. sion to reprint the articles included in this volwne.

&momic mul Politi,al Weekly for Sudipta Kaviraj, 'A Critique of

the Passive Revolution', 23, 45-7: 2429-44; Yogendra Yadav, 'Re­

configuration in Indian Politics: State Assembly Elections, 19931995', 31, 2-3: 95-104; T.V. �.athyamurthy, 'Impact of Centre­

State Relations on Indian Politics: An Interpretative Reckoning,

1947-1987', 24, 38: 2133-43; MS.S. Pandian, 'Culture and Subal­

tern Consciousness: An Aspect of the MGR Phenomenon', 24, 30:

pp. 62-8; Amrita Basu, 'When Local Riots Are Not Merely Local:

Bringing the State Back in Bijnor 1988-1992', 29, 40: 2605-21;

Rajni Kothari, 'Rise of the Dalits and the Renewed Debate on

Caste', 29, 26: 1589- 94 and Flavia Agnes, 'Protecting Women

Against Violence? Review of a Decade of Legislation, 1980-1989',

27, 17: WS19-33.

Living Media India Ltd for David Buder, Ashok Lahiri and Pran­

noy Roy, 'India Decides: Elections 1952-1995', in David Buder,

Ashok Lahiri and Prannoy Roy (eds), India Dtades: Ekaions 19521995, pp. 7-41.

Princeton University Press for James Manor, 'Parties and the

Party Sys tem', in Atul Kohli (ed;), India's Dmuxracy: An Analysis of

Changing Statt Society Relations, pp. 62-98.

Cambridge University Press for Paul Brass, 'NationaJ Power and

Local Politics in India: A Twenty-Year Perspective', Modern Asian

Studies, 18, 1: 89-118; Atul Kohli, 'From Breakdown to Disorder:

West Bengal', in Atul Kohli (ed.), Dtm()(Tacy nnd Discontent: India's

Gr<1Wing Crisis of Gov"7Jllhility, pp. 267-96, and Sanjib Baruah,

'Politics of Subnationalism: Society versus State in Assam', Modern

Asian Studies, 28, 3: 649-71.

Myron Weiner for 'India's Minorities: Who Are They? What

Do They Want?', in Ashutosh Varshney (ed.), Tht Indian Paradoz:

Essays in Indian Politia, pp. 39-75.

Dig1t1zeo by

Google

Origi�al rrom

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Contents

Figures

Introduction: A Political History of Independent

India

Partba Chatterjee

l

I. THE SYSTEM

I. A Critique of the Passive Revolution

Sudipta Kavirllj

41

45

II. THE INS1TIVTIONS

2. Parties and the Party System

89

92

James Manor

3. India Decides: Elections 1952-1995

DtlVid Butler, Asholt Lahiri and Prtm1WJ Roy

4. Reconfiguration in Indian Politics: State Assembly

Elections 1993-1995

125

5. Evolving Trends in the Bureaucracy

B.P.R. VithaJ

6. Impact of Centre-State Relations on Indian Politics:

An Interpretative Reckoning 1947-1987

T. V Satbyamurthy

7. Development Planning and the Indian State

208

Yogmdra Y

""8v

m.

Partba Chatterjee

THE POLmCAL PROCESS: DOMINANCE

8. National Power and Local Politics in India:

A Twenty-year Perspective

Paul Brass

D1g1t 1zeo by

Google

Orlgmal frcm

177

232

271

299

303

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

X

Contents

9. From Breakdown to Order: West Bengal

AtuJKDbJi

336

10. Culture and Subaltern Consciousness: An Aspect

of the MGR Phenomenon

367

11. When Local Riots are Not Merely Local: Bringing

the State Back in, Bijnor 1988-1992

390

M.S.S. Ptmditm

Amrita B1ZSU

437

IV. THE POLITICAL PROCESS:-RESISTANCE

12. Rise of the Dalits and the Renewed Debate on

Caste

439

13. India's Minorities: Who Are They? What Do They

Want?

459

14. Politics of Subnationalism: Society versus State in

Assam

496

15. Protecting Women against Violence?: Review of

a Decade of Legislation, 1980-1989

521

RAjni KDtbari

Myron Weiner

SanjibBaruab

Flavia Agner

A Bibliographic Guith

D1g1tizeo by

Google

566

Origlr.al from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Figures

3.1

3.2

3.3

3.4

3.5

3.6

3.7

5.1

9.1

Voter Tum-out, All-India

Voter Turn-out, Men and Women

Average Turn-out in Lok Sabha Elections

Unequal Size of Constituencies in 1991

The Impact of Drawing Boundaries on the Results

Splits in the Congress Party since 1952

The Janat2 Party and the BJP since 1977

Lines of Authority, Lines of Influence

Political Violence in West Bengal, 1955-1985

Digiti zed by

Google

Ongmal from

127

127

132

139

142

150

151

222

343

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Digi tized by

Google

Original frcm

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Introduction: A Political

Hi�tory of Independent India

Partha Chatterjee

H

alf a century may be considered a reasonable time for begin­

ning to write the outline for a political history of inde­

pendent India. The narrative which follows is a running thread

that connects the particular accounts and analyses contained in

the readings collected in this volume.

Continuities and Transformations

Territory

Independent India was created in August 1947 through a negotiated

act of transfer of power from the British rulers of a colonial empire

to the political leadership of two sovereign countries, India and

Pakistan. The· ,erritories of British India were partitioned between

the two new countries on a principle of religious majorities. Thus

provinces with Muslim majorities constituted the territories o_f

Pakistan, divided into two wings, one in the west and the other in

the east. Two provinces - Punjab and Bengal - were themselves

partitioned according to the religious composition of the district

populations in those provinces. However, even these principles had

to be applied with many qualifications, and several exceptions were

incorporated into the final award of the Radcliffe Commission

which undertook the task of actually drawing the lines of division

on the map of British India.

There were some 565 princely states over which the British exer­

cised pararnountcy without actually incorporating those territories

Dlgltlzedby

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

2 State and Politics in India

into the provinces of British India. According to the terms of the

transfer of power, the lapse of British paramountcy meant that the

rulers of those states regained full sovereignty, although they were

also given the option of joining either India or Pakistan. There was

furious diplomatic activity on t h e p- art of the new political auth­

orities of India and Pakistan in the days immediately preceding

independence to get the princes to sign the instruments of accession

to their respective dominions. Vallabhbhai Patel, the deputy Prime

Minister of India, took the initiative in this regard to put together

a single consolidated territorial entity over which the newly inde­

pendent Indian state would exercise sovereignty.1 The princes were

first asked to concede to the Indian union only the powers of

defence, external affairs and communications, and were invited to

continue participating in the upper house of the Dominion legisla­

ture where a new constitution was being made. In the end, most of

the princes of states surrounded by or contiguous to the territory

of India - 554 states, to be exact - agreed to join.

The states were scattered over many regions - in Kashmir and

the Punjab, in Rajasthan, in Gujarat and Saurashtra, in the Deccan,

in the Vmdhya regions of central India, in the Chhattisgarh area,

in Orissa, in Travancore-Cochin and Mysore, on the borders of

Bengal and in the Khasi hills. hnmediately after accession, a con­

certed attempt was made by the leadership in Delhi to consolidate

the territories of the states into larger administrative units similar

to the provinces. The legal forin of seeking the consent of the

ruler was maintained in each case, but the political argument of

the inevitability of popular democratic rule was frequently used,

often with telling effect. The rulers of the Orissa and the Chhattis­

garh states were persuaded to allow their territories to be merged

with the provinces of Orissa and Central Provinces, respectively;

in return, they were allowed a privy purse which they would enjoy

in perpetuity. This method of merger was also followed in the

case of the Deccan and the Gujarat states whose territories were

similarly joined with that of the province of Bombay, and for

several smaller states in other regions. Two hundred and sixteen

states were merged into provinces in this manner. The bulk of the

stat�s were, however, clustered in several contiguous areas in

Kathiawad, Rajasthan, Punjab, the Vmdhyas and central India.

I This is described in detail in V.P. Menon, Tbt Story ofthe lnttgrt,tiun ofthe

Indum StllUS (Bombay: Orient Longman, 1961).

Digi tized by

Google

Original frcm

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Introduction 3

After much negotiation, the rulers of these states agreed to form

unions of States called Rajmandals with one of them being called

the Rajpramukh and acting as the head of the union. Six such

unions were formed by integration, viz. Saurashtra, Vindhya

Pradesh, Madhya Bharat, Patiala and East Punjab States Union

(PEPSU), Rajasthan, and Travancore-Cochin, incorporating 310

states. Mysore, one of the largest states, became an administntive

unit on its own, as did a few others. Each union had its own

constituent assembly to draft a constitution for 'responsible gov­

ernment, and most rulers thought they would prefer some kind

of federal arrangement within their unions. However, some of the

states had active democratic movements, often allied with the

Indian National Congress, which played an important role in

shaping the political relations of the states with the Indian Union.

In the end, with the making of the Constitution of India in 1950,

all of the constituent assemblies of the Unions resolved to adopt

the Indian Constitution.

In three cases, however, there were difficulties with accession.

In Junagadh, a tiny state in Kathiawad surrounded by Indian

territory, the ruling prince signed up for Pakistan. The neighbour­

ing states had all joined India, the population was predominantly

Hindu and there was an active Congress movement in the state

which demanded unification with India. The matter became part

of the series of disputes that now flared up between India and

Pakistan and raised the crucial question of whether independence

was to be seen as the result of a legal transfer of power from one

authority to another or of the assertion of the democratic will of

the people. On the question of Junagadh, Pakistan insisted that

with the lapse of British paramountcy, each ruler had the right to

join either India or Pakistan irrespective of the geographical loca­

tion of'his state or the ethnic composition of its population. India

argued that if negotiations with rulers did not produce a satisfac­

tory agreement, the most fair and democratic way of resolving the

matter would be to hold a plebiscite among the people of the state.

Faced with growing popular agitation and pressure from the In­

dian authorities, the Nll,_wab of Junagadh decided in late October

1947 that he could not liold out any more and fled to Pakistan.

The administration of the state was taken over by the Indian

government and a referendum was held in February 1948 in which

there was an overwhelming vote approving the accession to India.

Digi tized by

Google

Original frcm

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

4 State and Politics in India

The Nizam of Hyderabad refused to join either of the dominions

and insisted on his right to head an independent and sovereign

kingdom. Negotiations for accession continued for several months

in which the Indian government made many concessions that had

not been given to the other states. At the same time, it also insisted

that if the Nizam was unwilling to accede, the matter should be

settled by a popular plebiscite which the ruling group in Hyderabad

was clearly reluctant to race. The Nizam, however, overplayed his

hand and in September 1948 Indian troops moved into Hyderabad.

The Nizam signed the instruments of accession on the same ternlS

as the other princes and in 1950 the Constitution of India came to

apply to Hyderabad.

InJarnmu and Kashmir too, the Manaraja did not sign in favour

of either dominion until late October 1947 when Parhan tribes­

men from across the border in Pakistan threatened to overrun the

Kashmir valley. On a request from the Maharaja for immediate

military assistance, the Indian government insisted that he fust

sign the instruments of accession, which he did. Indian troops

were flown in to Kashmir and after pushing back the raiders some

distance, a ceasefrre was agreed upon. The Maharaja in the mean­

time had agreed to nominate Sheikh Abdullah, the leader of the

National Conference, as Premier. When the Indian government

agreed to refer the dispute with Pakistan over Kashmir to the

United Nations, it pledged to hold a plebiscite in Kashmir under

UN auspices. This plebiscite, however, has never been held. Sub­

sequently, a separate constitution of Jammu and Kashmir was

promulgated in 1953; this was therefore the only former princely

state which finally got its own constitution, highlighting the very

special circumstances of its accession to India. The Jammu and

Kashmir constitution largely resembles the Indian Constitution

with the important qualification, however, that unlike,the other

states of the Indian union, the residual powers belong to the state

and not to the union. A part of the original territory of the princely

state lying beyond the line of ceasefire is still administered from

Pakistan by a government of Azad Kashmir.

There were two other vestiges of European colonial rule in

India: the Ponuguese colonies in Goa and in a few pockets on the

Gujarat coast, and the French settlements in Pondicherry and

Chandernagore. In 1954, following an agreement with France,

Pondicherry became part of India and was subsequently made a

Digiti zed by

Google

Ori ginal from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Introduction 5

.

Union Territory and Chandemagore was incorporated into West

Bengal. The Portuguese government, however, refused to give up

its colonial possessions and in 1960 Indian troops occupied Goa

and incorporated the Portuguese territories into India.

One can see, therefore, that there is nothing natural or im­

memorial about the territorial boundaries of independent India.

They exist as the result of a particular mode of transfer of power

from British colonial rule and of political negotiations between

the leaders of independent India and the rulers of the princely

states. The subsequent process of the consolidation of this ter­

ritory into a domain for the exercise of a new governmental power

is, of course, a part of the story of Indian politics since inde­

pendence. The only addition to that territory was the incorpora, �on in April 1975 of Sikkim as a constituent state of the Indian

union. Earlier, Sikkim was a sovereign kingdom which through

treaties with India had a protectorate status.

The Constitution

The Constituent Assembly which produced the Constitution of

the Indian republic in 1950 was not elected by direct universal

suffrage but was formed in 1946 as a result of indirect elections

by members of the different provincial legislatures who themsel­

ves had been elected by a very restricted electorate. After parti­

tion, as many as 82 per cent of the members of the Constituent

Assembly were from the Congress. However, the political leader­

ship was especially careful to include in the Assembly repre­

sentatives of a large range of opinion from different regions of

the country and sections of the population, including several

leaders such as B.R. Ambedkar, Shyama Prasad Mookerjee or

Mohammed Saadulla who during their political careers had often

been strongly opposed to the Congress. The Assembly also included many leg;u and constitutional experts.

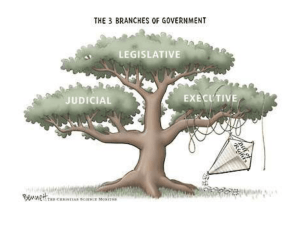

The radically new features of the constitutional system of in­

dependent India, when compared with that prevailing under

colonial rule, were, frrst, a sovereign legislature elected by direct

universal suffrage without communal representation but with re­

servations for the scheduled castes and tribes and, second, the

explicit constitutional guarantee of a set of fundamental rights of

all citizens. It provided for a parliamentary system of government

Dlgltlzedby

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

, St11te and Politics in India

of the British type with an executive responsible to Parliament but

with an indirectly elected President as the head of state. It also

provided for an independent judiciary with certain powers of

judicial review of laws made by Parliament

The Constitution was also a federal one, but of a very distinct

kind, with state governments responsible to directly elected state

legislatures and a distribution of powers between the union and

the states that was heavily inclined towards the union. As a federal

system, the Indian Constitution was far more centralized than

most federations elsewhere, and in this respect often closely fol­

lowed the provisions of the earlier Government of India Act of

1935.

The State Apparatus

The basic apparatus of governmental administration in inde­

pendent India was inherited from the colonial period, although

there soon occurred a huge incrc;ase in its size. It consisted of a

small elite cadre belonging to the all-India services and a much

larger corps of functionaries organized in the provincial services.

The Indian members of the Indian Civil Service, the much ac­

claimed 'steel frame' of the British Raj, were retained after In­

dependence, but a new service called the Indian Administrative

Service, modelled on the ICS, was constituted after 1947 as its

successor. The crucial unit of the governmental apparatus was

the district administration which, under the charge of the disttict

officer, was principally responsible as in colonial ti.mes for main­

taining law and order but was soon also to become the agency

for developmental work.

The basic structure of civil and criminal law as well as of its

administration was also inherited from the colonial period. The

major difference, of course, was in the creation of a Supreme

Court and its position within the new constitutional system. But

apart from the new issues that arose regarding the relation be­

tween Parliament and the judiciary, the working of the high

courts and district courts maintained an unbroken history from

colonial rimes, continuing the same practices of legal tradition

and ·precedent.

The Indian armed forces too maintained a continuing history

from the colonial period. The British ideology of a professional

Dlgltlzedby

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Introductum 7

army strictly under the control of the political leadership was

successfully maintained i n the period after independence, and

unlike most other countries, there was not even a joint command

of the anny, navy and air forces except in the office of the political

head of government.

Framework of a New Order

Tht Reorganization ofSt11tes

When the Constitution was inaugurated in 1950, the country was

divided into four kinds of states. The Part A states were former

provinces of British India, viz. Assam, Bihar, Bombay, Madhya

Pradesh, Madras, Orissa, Punjab, Utt2r Pradesh and West Benpl.

The Part B states were the products of the integration of the prin­

cely states; they were Hyderabad, Jammu and Kashmir; Madhya

Bharat, Mysore, PEPSU, Rajasthan, Saurashtra and Travancore­

Cochin. The Part C states were either the former Chief Com­

missioners' provinces or smaller units formed by the integration of

the princely states, viz. Ajmer, Bilaspur, Bhopal, Coorg, Delhi,

Himachal Pradesh, Kutch, Manipur, Tripura and Vindhya Pradesh.

Finally, there was a Part D state - the Andaman and Nicobar

Islands.

This particular structure did not follow any coherent principle

of organization of territories and was simply the result of a his­

torical cumulation. As f.ar as principles were concerned, the idea

that the units of India should be the linguistic provinces was

something that the Indian National Congress had upheld since

the rise of Gandhi. In 1919-20, the Congress had reorganized its

own provincial and district committee structure according to the

linguistic principle, disregarding the administrative units of British

India. Thus there were Maharashtra and Gujarat provincial com­

mittees in Bombay province, a Kerala PCC when there was no

Kerala, an Andhra PCC when there was no Andhra, and s o on.

In 1953, after a massive popular agitation, the Telugu-speaking

state of Andhra Pradesh was created. This brought up the question

of whether the entire structure of states in India should be reor­

ganized according to the linguistic principle. In 1954, a States

Reorganization Commission was set up to look into this matter.

Following its recommendations, the states were reorganized in

Dlgltlzedby

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

8 State and Politia in India

I 956. The distinction between the former provinces of British

India and the princely states was completely erased. Instead of the

four-tier stt11cture, there were now only states and union ter­

ritories. The linguistic principle was recognized in the formation

of states, but only partially. The principle, however, continued to

be asserted in mass agitations and in 1960 Bombay was divided

into Maharashtra and Gujarat,· while Punjab was divided into

Punjab and Haryana in 1966.

The Congress Party

Before Independence, the Congress had run some provincial gov­

ernments only briefly.and had joined the interim government a t

the centre only in 1946. Until that time, it was a mass party with

a well-developed organizational structure starting with village and

taluka units at the bottom and then, in ascendin!J order, district,

provincial and all-India committees, each elected by the lower

units. At the highest level, the All India Congress Committee

(AICC) elected a president and a working committee to look after

the regular functioning of the organization as a whole. After

Independence, the Congress was in charge of running the central

government as well as most of the state governments. It soon

became obvious that the entire focus of party activity would now

be on the performance of its governmental wing. But this also

meant a new centre of leadership around the Prime Minister and

his cabinet What would be the relation between the governmental

wing and the party wing? Should the Congress president and

working committee have a say in the making of decisions by a

Congress government? Or should a mass party of such long stand­

ing as the Congress accept that it must now follow the lead given

to it by government ministers?

These were the questions that were raised within the Congress

in the period immediately following Independence. Jawaharlal

Nehru was president of the Congress when he became Prime

Minister in the interim government in 1946. Soon after, he de­

cided to resign bis party post.J.B. Kripalani, the Congress Socialist

leader, succeeded Nehru but immediately ran into serious dis­

agreements with the ministerial wing over the issue of the relation­

ship between party and government. Nehru, along with bis senior

colleagues in gove.rnment, felt that the party should only provide

Dlgltlzedby

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

'

Introduction 9

long-term guidance in the matter of general policy and could not

expect the government to refer every decision to it for approval.

Kripalani, on the other hand, thought that the party's position was

being undermined. According to him it was the party which kept

in constant touch with the people in the villages and in towns and

reflected changes in their will and temper.

It is 'the party from which the Government of the day derives its

power. Any action which weakens the organization of the party or

lowers its prestige in the eyes of the people must sooner or later

undermine the position of the Governn1ent.2

In November 1947, Kripalani resigned as Congress president;

soon he would leave the Congress altogether along with many

other socialists.

Between 1948 and 1951, the issue of the relationship between

party and government remained at the centre of controversy

within the Congress. The underlying political tensions arose out

of the differences of some sections of Congress leaders with the

emerging policies of the Nehru government. The conservative

groups, in particular, were in favour of a much tougher policy

towards Pakistan and sharply opposed to the proposals for new

social legislation on the reform of personal laws and greater state

control over the economy. They decided to assert their' hold over

the party machinery in order to curb the autonomy of the govern­

ment in pursuing these policies. In the election of the Congress

president in 1948, Pattabhi Sitaramayya, the candidate put up by

Nehru's supporters, won a narrow victory. But in 1950, the right

wing was able to gain ascendancy with the election as president

of Purushottamdas Tandon. The death of Vallabhbhai Patel in

December 1950 deprived this group of its most powerful figure

within the government, and with the first general elections ap­

proaching, the tussle over control of the party organization

reached a climax. In August 1951, Nehru resigned from the

working committee, claiming that there were serious policy dif­

ferences between him and the party leadership. The parliamentary

party expressed its confidence in Nehru's leadership. Within a

few weeks, Tandon was forced to resign and the AICC elected

2J.B. Kripalani's speech to AICC'delegates, November 1947, cited in Stanley

A. Kochanek, The Congress PIIT'tJ oflnditl: Tbt l)yntmricsofOm-PartyDtm()(T11cy

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968), pp. 10-11.

Dig1t1zeo by

Google

Origi�al rrom

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

1 O State and Politics in India

Nehru as Congress president. For the moment at least, the

superiority of the government wing of the party was established

by creating a single unified leadership.

Nehru continued as Congress president until 1954. By then,

the Congress largely came to accept his view that the function of

the party was principally to carry to the people the message rep­

resented by the policies of the government. For the next decade

. or so, this remained the pattern of relationship between government and party. When U.N. Dhebar was elected Congress presi­

dent in 1954, he said quite clearly:

1t is a mistalce to consider that there is a dual leadership in the

country....There is only one leader in India todlly and that is Pandit

JawaharlaJ Nehru. Whether he carries the mantle of Congress Pre­

sidentship on his shoulders or not, ultimately, the whole country looks

to him for support and guidance.3

The Congress in the St11tes

Before 1967, the usual description of the party system in India was

'one-party dominance', the one party being, obviously, the Con­

gress.Sometimes it was also caJleq, simply, the 'Congress system'.

In the ftrst three general elections, the Congress won around 45

per cent of the votes and 75 per cent of the seats in Parliament.

Compared to that, the largest opposition party (the Socialist party

in 1951, the Praja Socialist party in 1957 and the Communist Party

of India in 1962) could manage only around 10 per cent of the

votes and less than 5 per cent of the seats. The concept of 'one­

party dominance' also implied a similar overwhelming position of

the Congress in all of the states. Clearly, this dominance had been

built up in course of the decades of organized political activity b y

the Congress in the nationalist movement in different parts of the

country. However, given the fact that substantial parts of inde­

pendent India were not part of British India, the Congress did not

always inherit a position of equal dominance in all the states at

the time of independence. In fact, in the 1950s, it was often in

those states which included large parts of the territories of former

princely states that the competition to the Congress was the

3 Speech by U.N. Dhebar,Janwry 1955, cited in Kochanek. Ctmgrtss P11rty,

p. 61.

Dlgltlzeo by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

lntroduaion II

strongest - states such as Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Madhya

Pradesh, Manipur, Orissa, Punjab, Rajasthan and Tripura.

Despite some variations in strength, however, the Congress did

rule in every state until 1967. The only exceptions wereJammu and

Kashmir where it was the National Conference which was the

ruling party (although from 1953, after the removal and arrest of

Sheikh Abdullah, the National Conference under Bakshi Ghulam

Mohammed virtually became the Kashmir unit of the CongrC$),

Kerala which had a CPI-led government for a brief period in

1957-9 (a government that was removed by central intervention)

and Nagaland which became a state in 1963 and had a Na ga

National Organization government.Just as the governmental wing

of the Congress asserted its dominance over the party at the centre,

so did Congress rule in the states focus around powerful Chief

Ministers.

An interesting characteristic of the one-party dominance system

i n the Nehru period was the large degree of autonomy that the

provincial party units were able to assert in relation to the central

party leadership. The PCCs largely became financially independ­

ent, raising their own party funds for running the organization or

fighting elections and distributing patronage through their mini­

sters in the state government. Their recommendations for can­

didates for parliamentary or assembly seats were almost always

accepted without modification by the central leadership, except

when the state party was de,eply divided. Congress politics in

the states was dominated in die Nehru period by powerful Chief

Ministers like N. Sanjiva Reddy (Andhra Pradesh), B.P. Chaliha

(Assam), Sri Krishna Sinha (Bihar), Y.S. Parmar (Himachal

Pradesh), S. Nijalingappa (Mysore), Y.B. Chavan (Maharashtra),

H.K. Mahatab (Orissa), Pratap Singh Kairon (Punjab), Mohan Lal

Sukhadia (Rajasthan), K. Kamaraj (Madras), Sampoornanand and

C.B. Gupta (Uttar Pradesh) and B.C. Roy (West Bengal), or

occasionally by party bosses such as S.K. Patil in Bombay or Atulya

Ghosh in West Bengal who worked in close association with their

respective Chief Ministers. The influence and autonomy of the

state units in the Congress party structure were shown most clearly

in 1964 when the successor toJawaharlal Nehru as Prime Minister

was effectively chosen by Kamaraj as Congress pr�ident in as­

sociation with the Chief Ministers and party presidents of the

major states.

Dig1t1zeo by

Google

Origi�al rrom

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

I2 State and Politics in India

The Developmental State

Apart from the dominance of the Congress at the centre and in the

states, a very important feature of the framework of political rule

, established in the Nehru period ,vas the developmental state, inter­

' vening in the economy, planning and guiding its growth and trying

1 directly to promote the welfare of the population. This was perhaps

I, the principal governmental function t;hat legitimized the position

of the Congress leadership within the new post-colonial state.

It meant considerable state intervention in the economy, not

only through progressive taxation of personal and corporate in­

comes or the provision by the state of public services such as

education, health and transport, all of which had become hallmarks

/ of the new welfare state even in advanced capitalist economies in

the period after World War II. In addition, the state in India in

the Nehru period consciously chose elements from socialist re­

1

. gimes such as the Soviet Union in order to create a planned

/ economy, albeit within the framework of a mixed and not a so­

l cialist economy, where the state sector would control the 'com­

i manding heights of the economy'. The idea was to industrialize

··, rapidly by setting up new public enterprises in areas such as metals,

, minerals, machine building, chemical industries, fuel, power and

J transport through direct investments by the state. Private capital

1

! was meant to be confined primarily to the consumer and inter­

/ mediate goods sectors. Rapid industrial growth was seen to be the

· key to the removal of poverty in the country and the provision of

welfare for the people.)A Planning Commission was set up as an

expert body relatively ihdependent of the central government with

the function of defining the goals and strategies of development

and carrying out investment planning. Although the First Five

Year Plan was launched in 1951, it was really with the Second Five

Year Plan (1956-61), prepared under the guidance of

P.C. Mahalanobis, that the characteristic strategy ofIndian indus­

trialization in the Nehru period was inaugurated.

The Interregnum

End of the Nehru Era

Before speaking of how the framework of political rule built i n

the Nehru period became unsettled, one further feature of that

D1g1t 1zeo by

Google

Orlgmal frcm

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Introduction I3

framework - India's foreign policy - must be mentioned. Since

this will be the subject of a separate volume in this series, foreign

policy will not-be discussed at any length in this volume. Neverthe. less, a description of the political order in the Nehru period, and

even of its economic strategy, will be incomplete without a mention

of the policy of non-alignment. The policy was developed in the

context 9f the bipolar world that emerged after World War II with

two rival military blocs around the two super powers - the United

States and the Soviet Union - claiming to represent two opposed

economic and political systems and, indeed, two contending paths

of social development. The Indian policy of non-alignment sought

to strike a middle ground by refusing to align with either military

bloc and choosing a path of state-sponsored development within

the social framework of capitalist democracy. Pursuing this foreign

policy, the Indian government under Nehru sought to build up a

third bloc of non-aligned nations consisting largely of the newly

independent countries of Asia and Africa, and to seek the aid of

both the Western and the socialist blocs in the economic and

technological fields.

The border war with China in 1962 was the first major occasion

when the wisdom of Nehru's foreign and defence policy was

seriously questioned at home. Indian positions at several places

along the disputed Himalayan border had to be abandoned as its

troops retreated; the policy of non-alignment too seemed to lose

credibility because India now had to seek military aid from the

United States. Nehru's biographer writes: 'No one who lived in

India through the winter months of 1962 can fo:-Eet the deep

humiliation felt by all Indians, irrespective of party. Criticism of

Nehru's leadership began to be voiced both within and outside

the Congress. Hardly a year after the general elections of 1962,

which the Congress had, as expected, won, its candidates lost three

by-elections to J.B. Kripalani, Ram Manohar Lohia and

M.R. Masani, three of the government's bitterest critics. In August

1963, for the first time in sixteen years in power, Nehru's govern:­

ment faced a no-confidence motion in Parliament. There were

also reports of Nehru's deteriorating health.

The origins and motives of the so-called Kamaraj Plan have

been a subject of conq-oversy: it has often been attributed to

4 Sarvepalli

Gopal,]1TW11har/al Nthnl:A Biography (Delhi:

Oxford University

·

Press, 1984), vol. 3, p. 232.

.

Digi tized by

Google

Original frcm

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

14 Statt and Politics in India

discussions between two Chief Ministers - Kamaraj of Madras

and Biju Patnaik of Orissa.5 The Plan,· as proposed by Kamaraj

and accepted by the Congress Working Committee in August

1963, was to ask leading Congressmen in government to leave

their posts and devote themselves to the task of revitalizing the

party organization. Accordingly, front-ranking ministers such as

Morarji Desai, Lal Bahadur Shastri, S.I(. Patil and Jagjivan Ram

and Chief Ministers such as Kamara;, Biju Patnaik, C.B. Gupta,

Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed and Binodanand Jha of Bihar re­

signed from their governments. In October 1963, K Kamaraj

was elected Congress president.

The Kamaraj plan has been interpreted in many ways: as

Nehru's ploy to reassert his control over the party, as an attempt

by left-wingers to remove Morarji Desai and S.K Patil from the

government, as a preemptive strategy for a possible battle o f

succession. As events unfolded, it became clear that the most

significant effect ofthe plan was to give to the Congress presidency

and the working committee a degree of authority they had not

enjoyed for many years. Indeed, as factional and ideological loyal­

ties were put to the test in those months of crisis, the most

powerful group that formed within the Congress was precisely

around the new party president. Popularly dubbed the Syndicate,

the group comprised Kamaraj, Sanjiva Reddy, Nijalingappa, S.K

Patil and Atulya Ghosh, all of them Chief Ministers or party bosses

from non-Hindi-speaking states. When Nehru died in May 1964,

it was the Syndicate which secured the election by the parliamen­

tary party of Lal Bahadur Shastri as the next Prime Minister.

The most important event in Shastri's brief tenure as Prime

Minister was the war with Pakistan in October 1965. I t raised his

stature immensely and at public meetings he drew crowds as large

as Nehru did before him. He worked closely with Kamaraj as party

president and in August 1965 played a crucial role in securing,

against the open challenge put up by Morarji Desai, Kamaraj's

reelection to the post.

Lal Bahadur Shastri died inJanuary 1966. This time the work­

ing committee was unable to secure a unanimous succession since

Morarji Desai insisted on a vote. The Syndicate decided to put up

S Michael Brecher, Nth"'� M11ntlt: Tbt Politics of Sucarsion in JndiJ, (New

Yorlt: Frederick A. Praeger, 1966).

D1g1t 1zeo by

Google

Orlgmal frcm

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Introduction 15

Indira Gandhi as its nominee. The Congress members of parlia­

ment chose her against Morarji Desai by a huge margin. Once

again, the powerful group of regional party leaders assened its

hold over the central structure of political rule.

.•

The 1967 Ekctions

By this time, however, some of the problems of the economic

strategy of rapid industrialization began to be felt. By the middle

o f the 1960s, there was an acute food shortage in the country,

making it necessary for the government to import large quantities

o f foodgrains. There was also a severe foreign exchange crisis,

exacerbated by hugely increased defence expenditures. Soon after

its formation, therefore, Indira Gandhi's government was forced

to go in for a large devaluation of the Indian rupee. With high

food prices and a slowing down of growth, economic hardship was

at its peak. This was reflected in massive, and often violent, politi­

cal agitations all over the country.

In this situation, it was only to be expected that in the 1967

elections the Congress would not repeat its earlier overwhelming

victories. But the setbacks that occurred surprised even the pes­

simists. The Congress vote dropped by almost 5 per cent, and

while it had held 74 per cent of the seats in the previous parliament,

it now managed to win only 54 per cent. Even more stunning was

the number of states in which it failed to win a majority (or lost

it because of defections soon after the elections): there were as

many as nine states - Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya

Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, Orissa, Madras and Kerala -which

now had non-Congress governments. This brought in a complete­

ly new situation in Indian politics, not only because the Congress

had lost its overwhelming dominance at the centre but also because

the federal structure was now called upon to deal with the relations

between a Congress government at the centre and several non­

Congress governments in the states.

Non-Congress G(f1Jernmmts

Although the Congress was defeated in several states in 1967, it

was not replaced in power by a single party, except in the case

of Madras where the DMK won an absolute majority and

Digi tized by

Google

Original frcm

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

16 State and Politics in India

C. Annadurai became Chief Minister. The non-Congress gov­

ernments that were formed in the other states were coalitions of

several parties, often having little ideological similarity, even

though a common minimum programme was usually formulated.

Thus in J3ihar, a Samyukta Vidhayak DaJ was formed between

the SSJ?; the PSP, the Jana Sangh, the Jan Kranti Dal (which

later merged with the Bharatiya Kranti Dal) and the CPI. The

SVD commanded a majority in the assembly and Mahamaya

Prasad Sinha of the JKD became the first non-Congress Chief

Minister of Bihar. In Punjab, all the non-Congress parties in the

assembly - the Akali Dal (Sant Group), the CPl(M), the CPI,

the Jana Sangh, the Akali Dal (Master Group), the SSP and the

Republican Party - came together to form a Popular United

Front which elected Gurnam Singh of the Akali Dal (Sant Group)

as its leader and Chief Minister. In West Bengal, the two non­

Congress fronts, one led by the C.Pl(M) and the other by the

Bangla Congress, came together to fonn the United Democratic

Front consisting of fourteen parties. Ajoy Mukherjee of the

Bangla Congress became the first non-Congress Chief Minister

of West Bengal. In· Kerala, a United Front ministry headed by

EM.S. Namboodiripad of the CPl(M) came to power. In Orissa,

the Swatantra Party, consisting mostly of former princes, formed

a coalition ministry under R.N. Singh Deo with a breakaway

Congress group called theJana Congress, led by the former Chief

Minister, H.K. Mahatab.

In Haryana, where the Congress had won an absolute majority

in the elections, the government of Bhagwat Dayal Sharma was

defeated in the assembly within a week of assuming office. A large

chunk of dissident Congressmen left the party and joined the

opposition. A United Front was formed and Rao Birendra Singh

became its leader and Chief Minister. In Madhya Pradesh too,

there were defections from the Congress, exemplified in particular

i

by Vjay Raje Scindia, the Rajmata of Gwalior, who left the Con­

gress and declared her support for the Jana Sangh. Four months

after the elections, the government of D.P. Mishra was defeated.

An SVD ministry, led by G.N. Singh and consisting of Congress

defectors, the Rajmata's group, the Jana Sangh, the SSP and the

PSP, came to power. In Uttar Pradesh, the Congress could not

win an absolute majoiity and was also hampered by a leadership

tussle between C.B. Gupta and Charan Singh. Nevertheless, the

D1g1t 1zeo by

Google

Orlgmal frcm

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Introduction 17

Governor asked C.B: Gupta to form the ministry. Three weeks

later, the government collapsed when Charan Singh, along with

his followers, joined the opposition. Charan Singh became Chief

Minister of an SVD ministry.

However, it was not as though one-party dominance was re­

placed by an alternating party system. The coming together of

opposition parties to form non-Congress governments in the

states did not produce the consolidation of an alternative ideo­

logical or organizational formation, nor indeed, as would soon

become clear, did it mean the end of Congress dominance. Soon

after their formation, the non-Congress governments were them­

selves thrown into crises as they failed to hold their ranks together.

Defections became the order of the day as, one after the other,

the United Front governments in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West

Bengal, Haryana, Punjab and Madhya Pradesh were ousted. A

Congress government was installed in Madhya Pradesh with the

support of defectors, while governments of defectors were in­

stalled with Congress support in Bihar, West Bengal and Punjab.

Even these did not last long and president's rule was imposed in

Haryana, West Bengal, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Punjab. It has

been calculated that whereas in the ten-year period between 195 7

and 1967 there had been in all of India a total of 542 legislators

changing parties, in a single year following the 1967 elections

there were as many as 438 defections.6

This period of the formation and collapse of non-Congress

governments in the states also for the first time turned into a major

controversy the question of centre-State relations and especially the

role of the Governor. In Rajasthan, where no party had an absolute

majority, Sampoornanand, the Governor, faced a barrage of criti­

cism when, after much prevarication, he decided to ask Mohan Lal

Sukhadia as the leader of the single largest party to form the

government. Sampoornanand was accused of having acted in a

partisan manner since he refused to consider the loyalties of inde­

pendents, many of whom had expressed their support for the

non-Congress United Fl'bnt. The protests led to a situation of

serious unrest, forcing the Union government to declare Pres­

ident's rule in Rajasthan for a few months. In Haryana, where

defections by legislators reached the most extreme limits, Governor

6 Subhash C. Kashyap, 11,e Politia ofP(IWer: Defections 1171dState Politics in India

(Delhi: National, 1974), p. 15.

Dlgltlzedby

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

18 St11te and Politics in India

B.N. Chakravarty recommended President's rule even when Rao

Birendra Singh's ministty commanded a majority since he felt the

government had lost stability and was only retaining its majority by

engineering repeated counter-defections. In West Bengal, in a

situation of growing industrial and agrarian unrest and dissensions

within the ruling UDF, the Governor Dhanna Vira, after urging

the Chief Minister to set an early date for a trial of strength in the

assembly, dismissed Ajoy Mulcherjee's government and installed a

minority ministry formed by defectors with Congress support. The

action was roundly criticized and led to widespread unrest cul­

minating in the imposition of President's rule.

The Congress Split

The 1967 elections were a severe blow to the Congress. Not only

was the party ousted from power in several states, the period

immediately before and after the elections also saw a tremendous

weakening of its internal strength, with constant dissension and

acrimony in the ranks, rampant factionalism and a tide of defec­

tions. There was a general feeling that the old guard was too set

in its conservative ways, mired in corruption and out of touch with

the people. The so-called Young Turks belonging to the Socialist

Forum within the Congress, who now gathered around Indira

Gandhi, were particularly strident in their criticism of the party

bosses and blamed them for the election debacle. The Syndicate,

on the other hand, began to feel that the Prime Minister was

moving away from party control and trying to build up an auto­

nomous centre of power.

Things came to a head at the Baµgalore session of the AICC

in July 1969. Indira Gandhi presehted to the Congress a set of

'stray thoughts' on economi<policy, arguing for land reforms,

restriction of monopolies, nationalization of banks and other

radical measures. Although leaders like Morarji Desai were vocal

against the proposals, the Syndicate members were quick to see

that to oppose them would mean further unpopularity. The Prime

Minister's note was passed by the AICC. The Syndicate struck

back when the time came to select the Congress candidate for

the upcoming Presidential election. Indira Gandhi had suggested

the names ofV.V. Giri, theVice-President, or Jagjivan Ram, the

most prominent scheduled caste member of her cabinet. But the

Digi tized by

Google

Original frcm

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Introduction 19

Congress parliamentary board overruled her suggestion and in­

stead nominated N. Sanjiva Reddy.

As soon as the Ban galore session ended, Indira Gandhi re­

moved Morarji Desai from her cabinet, took up the finance

portfolio herself and announced the nationalization of fourteen

major banks. At the same time, V.V. Giri decided to contest the

election for President as an independent candidate and appealed

for a 'vote of conscience'. Nijalingappa, the Congress president,

asked for a whip to be issued requiring all Congress legislators

to vote for Sanjiva Reddy, the official candidate. Jagjivan Ram

and Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed, acting on behalf of Indira Gandhi,

declared that all legislators must be allowed to vote 'according

to their conscience'. It was a trial of strength between the Syn­

dicate and Indira Gandhi, with parties like the Communists, the

other left parties, the Akalis, the DMK and the Muslim League

supporting the latter. Giri won the election on second preference

votes, securing a majority in the Parliament and in eleven of the

states. While the Congress was split right down the middle, that

itself would turn out to be a major triumph for Indira Gandhi.

The Prime Minister's supponers now demanded a requisition

meeting of the AICC to elect a new Congress president. In

November 1969, two rival meetings, both claiming to be of the

working committee, were held at the same time, one presided

over by Nijalingappa and the other by Indira Gandhi. A few days

later, Nijalingappa's working committee expelled Indira Gandhi

from the pany, whereas the Congress parliamentary pany, at­

tended by 330 out of 432 members, declared this move 'invalid

and unjustified'. It was clear that Indira Gandhi had asserted her

hold over a majority of Congress parliamentarians. Outside the

party, her, popularity was at its peak. A requisitioned AICC meet­

ing was held in November 1969 at which Nijalingappa was re­

moved from the post of party president. A month later, Jagjivan

Ram was elected president of what was now called the Congress

(Requisitionists).

Sixty-two Congress members of the Lok Sabha had declared

their opposition to the Prime Minister and, forming a bloc called

the Congress (Organization), had joined the opposition. Indira

Gandhi's government was now reduced to a minority but con­

tinued in office with the support of the DMK, the CPI, the Akali

Dal, the Muslim League and some independents. In September

Digiti zed by

Google

Ori ginal from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

20 State and Politics in India

1970, Indira Gandhi moved a constitutional amendment for the

abolition of privy purses and privileges of the former rulers of the

princely states. The amendment was very narrowly defeated in the

Rajya Sabha, upon which privy purses were abolished by a Pres­

idential order. The order was then struck down as unconstitutional

by the Supreme Court. In December 1970, the Prime Minister

decided not to continue any further with her minority govern­

ment. For the first time since Independence, Parliament was dis­

solved before completing its full tenn when Indira Gandhi asked

for fresh elections.

The Congress Restoration

The 1971 Elections

At the time of its dissolution, the Lok Sabha of 523 seats had a

party composition in which the Congress (R) had 228 members,

the Congress (0) 65, the Swatantra Party 35, the Jana Sangh 33,

the DMK 24, the CPI 24, the CPl(M) 19, the SSP 17 and the

PSP 15, besides members of other smaller parties and independ­

ents. For the 1971 elections, Indira Gandhi received the support

of the CPI, the DMK, the Akali Dal and a section of the PSP. But

she faced an opposition alliance consisting of the Congress (0),

the Jana Sangh, the Swatantra Party, the SSP and the BKD. Indira

Gandhi's election campaign was stridently populist, the principal

slogan being garibi hatao (remove poverty). It was the most massive

election campaign undertaken in India until that time. It was also

the first time that elections to Parliament were separated from

elections to the state assemblies, making national issues the ex­

clusive focus of the campaign.

The results were a surprise even to her supporters. The Con­

gress (R) won 350 seats, while the parties of the opposition alliance

were routed. Even in the Congress (0) strongholds of Mysore and

Gujarat, it was a sweep for the Congress (R). Only the DMK and

the Left parties, many of which were now aligned with Indira

Gandhi, retained their strength. Ideologically, there seemed to

have occurred a decisive leftward swing in the country as a whole.

In 1971 again, the political leadership in East Pakistan declared

its autonomy from the western wing of the country. There was

virtual military occupation of East Pakistan and a massive influx

Digi tized by

Google

Original frcm

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

lntroduaum 21

of refugees across the borders into West Bengal and Tripl11"2.

Indira Gandhi at this time made a series of international diplo­

matic manoeuvres - signed a treaty of friendship with the Soviet

Union, withstood the pressures exerted by the United States and

launched a war to liberate Bangladesh. The military action was

well-planned and swift and the Pakistan army in the eastern sector

surrendered within two weeks. The Bangladesh war boosted Indira

Gandhi's image to unprecedented heights and she began to be

acclaimed as the leader of one of the world's more powerful

nations. It also sealed the close ties between her government and

that o f the Soviet Union.

Indira's Congress

To understand the structure of the restored Congress under Indira

Gandhi and how it differed from the Congress in Nehru's time,

we will have to consider the changes that had taken place in the

country in the two decades since Independence. Many of these

changes were, in f.act, the direct result of the policies and actions

of the government in the Nehru period.

First of all, the idea was now fmnly established that the state was -:,

the principal, and in many instances the sole, agent of bettering the 'I

condition of the people and providing relief in times of adversity. _

Unlike in the days before Independence, when most modem in­

stitutions of education, health, culture, sports or social welf.are in

the country had been set up through voluntary action, by raising

contributions from both rich and poor and often under the leader­

ship of nationalist political organizations, now the general expecta­

tion among all classes of people was that _the state must perform

this role. The performance of particular parties and leaders came

to be judged by how much they had 'done' for their respective

constituents.

Second, the particular strategy of economic development fol­

lowed in the Nehru period produced a division between large

public undertakings in the capital goods and infrastructure sectors

and private capitalists, dominated by a few monopoly houses, in ·,

the consumer goods sector. The public sector grew rapidly and �

the urban middle class and a large section of the working class

became dependent upon its-further expansion. Agricultural growth

did not receive much attention and by the mid- l960s there was a

Dlgltlzeo by

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

22 State mul Politics in India

massive food crisis. To tackle this, a strategy for a quick increase

in foodgrains production through state subsidy of irrigation water,

seeds and fertilizers, and government support for minimum food­

grain prices was formulated. Widely known as the 'green rev­

olution', this strategy relied heavily on the enterprise of larger

farmers and was first tried out in the better irrigated zones of

Punjab, Haryana and western UP. This meant, however, that a

new organized class interest - that of the rich farmer - would

now become a player in national politics.

Third, the political consolidation that the Congress represented

as the principal organization of the freedom struggle was now a

thing of the past. Most of the leaders of the major opposition

parties were themselves former Congressmen who were now no

longer prepared to engage in working out a political consensus

under the aegis of the Congress. Even within the Congress, the

problem of establishing a harmonious relationship between the

government and the party, which was first resolved in favour o f

the former in the early 1950s and swung towards the latter after

Nehru's death, became a bitterly contentious issue in the. late

1960s.

The restoration of the Congress under Indira Gandhi relied on

several new political strategies. Following the split, the Congress

(R} became an organization that derived its identity from its leader.

This was not merely symbolic, because even in its organization

the Congress now became strongly centralized, with power flow­

ing directly from the central high command. The older phe­

nomenon of Congress rule through strong Chief Ministers was

gone: Chief Ministers were now virtually nominated from the

centre and held office only as long as they enjoyed the confidence

of the high command. Between 1968 and 1989, there were as many

as fourteen Congress ministries in Bihar with nine different Chief

Ministers; in UP, between 1970 and 1988, there were ten Con­

gress ministries and seven Chief Ministers; in Maharashtra, be­

tween 1975 and 1988, there were eight Congress ministries and

five Chief Ministers; in Andhra Pradesh, between 1971 and 1982,

there were six Congress Chief Ministers.

Second, the developmental ideology of the Nehru era was

now purveyed in a new rhetoric of state socialism with the

1 central executive structures of government playing the pivotal

role. Other structures of government such as the j�diciary, or

D1g1t 1zeo by

Google

Orlgmal frcm

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

lntroduaiOJI 23

the local bureaucracy, or local political leaders were frequently

criticiud for being conservative, corrupt, and acting as hindran­

ces to development.

Third, welfare packages were now targeted towards specific

groups of the population, such as scheduled castes or tribes, or

minorities, or workers, or women, and delivered in such a way as

to produce the impression that they were a gift of the central \

leadership, Indira Gandhi in particular. In fact, the traditional _J

pattern of Congress support - a somewhat paradoxical alliance

of urban elites and rural landholding castes at the top with low

castes and minority groups below - was accentuated and

strengthened in this period. However, whereas the older Con­

gress, with its loose consensual structure, also relied on a populist

ideology, the populism of Indira Gandhi's Congress W2S far more

centraliud, statist and focused on a single leader.

One particular aspect of the new strategy deserves special

mention - namely the reorganization of the north-eastern re­

gion. After Independence, this region of the Indian union was

administratively organized within the state of Assam, with the

two former princely states of Manipur and Tripura becoming

union territories in 1956. However, within Assam there were

major natural, social and political differences between the plains

and the hill regions. The latter, which was almost entirely in­

habited by tribal peoples, was administered in the 1950s through

elected autonomous district councils which had some limited

legislative powers. However, there was resistance in many areas

to the new order. The Naga National Council under the leader­

ship of Angami 2.apu Phiw organiud a complete boycott of the

first general elections in the Naga Hills district where not a single

nomination paper was submitted and not a single vote was cast.

The insurgency continued in the Naga Hills for most of the nen

two decades, requiring the constant p�nce of Indian army

troops i n the area. Insurgency also arose in the Miro hills in the

1960s and the Miro National Front, led by Laldenga, was out­

lawed. Even in the Khasi and Garo hills, where the Congress

had secured a strong following within the political leadership, the

1967 elections proved to be a major setback when the Congress

lost most of the seats to the opposition All-Party Hill l!.eaders'

Conference. In 1972, the union government effected a major

reconstitution of the region by giving full statehood to Meghalaya,

Dlgltlzedby

Google

Original from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

24 State and Politia in India

Manipur and Tripura and making Arunachal Pradesh (the former

North-East Frontier Agency) and Mizoram union territories. The

move certainly made possible a political settlement of the unrest

in · the hill states in the subsequent years, although it did not

necessarily improve the position of the Congress in all the new

states.

Unrest and Repression

Despite Indira Gandhi's massive electoral victory in 1971 and the

success of the Bangladesh war, the political scene at this time was

marked by considerable unrest. This came from both ends of the

political spectrum. On one side, there were large-scale agitations

led by the communists and other left parties among the middle

classes and workers in industrialized states such as West Bengal.

To some extent, the nationalization of banks and mines, and an

expanding public sector were meant to satisfy these interests.

However, the industrial economy did not show signs of revival

and, following the international oil crisis of 1973, there were huge

price rises. In 1974, there was a massive country-wide strike by

railway workers that was ruthlessly crushed.

From the late 1960s, there was also unrest among peasants in

many parts of the country. Espe cially in the most backward

agricultural regions where feudal-style oppression' by landlords

and state officials still prevailed, there now occurred locally or­

ganized resistance by poor peasants and agricultural labourers,

often belonging to low-caste or tribal groups. One such move­

ment in a place called Naxalbari in the foothills of Darjeeling

district in West Bengal suddenly came into prominence in 1967

when the local organizers belonging to the CPI(M) clashed with

the party leadership which wanted them to withdraw the move­

ment in the interest of saving the United Front ministry in West

Bengal. By 1969, the radical groups split from the CPI(M) and

formed their own party called the CPl(M-L). 'Naxalite' peasant

movements spread in West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala,

Bihar and Punjab, and in all cases were suppressed by the use of

massive armed force by state agencies.

It was at this time that, alongside a centralized developmental

ideology, there also grew a hugely expanded central machinery of

police and paramilitary forces for use against political movements.

D1g1tizeo by

Google

Origlr.al from

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

lntroducticm 25

The Defence of India Rules, handed down from colonial times,

were widely used against political opponents, and in 1971 a Main­

tenance of Internal Security Act (MISA) was passed specifically

for tackling political agitations. The Central Reserve Police Force

and the Central Industrial Security Force were also set up at this

time, as was the Border Security Force which too was often de­

ployed for internal security purposes. Finally, there was the Re­

search and Analysis Wmg (RAW), the intelligence agency of the

government, directly under the charge of the Prime Minister.

The waves of unrest that spread through India in the early 1970s

were not confined to Communist agitations. In many parts of

northern India, especially in Bihar, and then in 1974 in Gujarat,

there was widespread agitation against corruption in government,

initially led by students but soon ta.king on the form of a popular

anti-government movement. Some of the ideological and organ­

izational inspiration here was provided by the Socialist followers

of the late Ram Manohar Lohia as well as by Gandhian activists,

and at various stages most opposition parties except the Com­

munists joined the movement. But it was galvanized by the leader­

ship given to it by Jaya Prakash Narayan who emerged from

political retirement to announce a call for 'total revolution'. This

too was a populist movement, making general demands that voiced

the discontent of large sections of the people and specifically

targeted against the ruling government. But Congress populism

at the time of Indira Gandhi was, as one commentator has put it,

a 'jealous populism', utterly intolerant of rival populist mobiliza­

tions, and hence violently repressive.7

The government dubbed the movements in Bihar and Gujarat

anti-national and fascist, and came down on them with a heavy

hand. In June 1975, the Allahabad High Court delivered a judg­

ment on a petition against Indira Gandhi's election to the Lok

Sabha in 1971. Finding her guilty of electoral malpractices, the

court set aside her election. The opposition parties now began to

clamour for her resignation and Jaya Prakash Narayan, at a huge

rally in New Delhi on 25June 1975, declared that the government

had lost all moral claims to rule. That night, a state of emergency

was promulga'ted in India.

7 David Selboume, A.n Eye to India: Tht Umnaslting of a Tyr111111J

mondsworth: Penguin, 1977), p. 90.

·-·

Dlgltlzeo by

Google

Original from

(Har­

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

26 State and Politics in India

The Emergency

Tens of thousands of opposition leaders and activists from all

over the country, including fifty-nine members of Parliament,

were arrested during the emergency. They were from the Socialist

Party, the Congress (0), the CPl(M), the CPI(M -L), the Alc:ali

Dal, the DMK, the Bharatiya Lok Dal and the Jana Sangh. A

few of those arrested were critics of Indira Gandhi from within

the Congress. Twenty-six political organizations from both left

and right were banned, including the CPI(M-L) and most other

'Naxalite' groups, the RSS, the Ananda Marg and the Jamait-c­

Islami. Censorship was imposed on the press and the fundamental

right of equality before the law (Article I4), the right to life and

liberty (Article 21) and protection against arbitrary arrest (Article

22) were suspended. MISA was strengthened by making it vir­

tually unnecessary for the authorities to give .any reasons

· for

detaining a person.

.

The DMK government in Tamil Nadu (as Madras was called

from 1969) was removed for its 'economic failures' in January

1976 and President's rule imposed. In actual fact, the DMK had

resisted the enension of the emergency regime i n Tamil Nadu

and the Chief Minister M. Karunanidhi had publicly called for

an end to authoritarian rule. In March 1976, the only other

non-Congress government in the country, the coalition rninistry

in Gujarat headed by Babubhai Patel of the Congress (0), was

similarly dismissed for its alleged failure to maint2in law and

order. Now all st2tes in India either had Congress governments

or were under President's rule.

A week after the emergency was declared, the government

announced a 20-point programme to 'change the face of India in

a truly revolutionary manner'. It included implement2tion of land

reforms, liquidation of rural indebtedness, abolition of bonded

-labour, socialization of urban land, prevention of tax evasion and

punishment to economic offenders, participation of workers in

industric;s, and special beneftts to the landless, agricultural