From Culturally Competent to Anti-Racist---Types and Impacts of Race-Related Trainings (1)

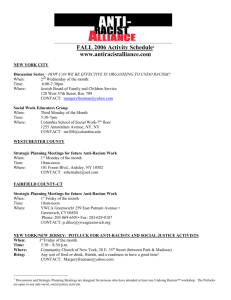

advertisement