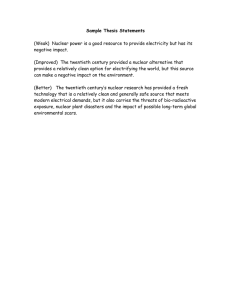

Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk Anti-Nuclear Mobilisation (ANM) and environmentalism in Europe: a view from Portugal (1976-1986). Stefania Barca Ana Delicado Abstract The article addresses the rise of antinuclear mobilization (ANM) in Portugal in the 1970s against the backdrop of similar movements across Western Europe. After performing a brief review of the literature on social mobilisation against nuclear energy, an overview is provided of the available sociological literature on environmental mobilisation in Portugal, mostly developed in a comparative southern-European perspective. The second section adds new empirical evidence on Portuguese ANM, and its connection with environmental mobilisation, based on in depth research conducted through both archival scrutiny and oral history interviews. In the conclusion, a fresh perspective is offered on the contribution of the Portuguese case to the advancement of research on the relationship between anti-nuclear and environmental mobilisation in Western Europe INTRODUCTION On the morning of 15 March 1976, a crowd of about one hundred people gathers at the church square of the Portuguese village of Ferrel, roughly 100 km north of Lisbon, and marches towards a place called Moinho Velho (Old Mill) where, against the will of local citizens and administrators, constructions have begun for the first nuclear power plant of Portugal. Celebrated as the birthplace of the Portuguese environmental movement, Ferrel is also an emblem of the many different, at times contradictory elements which, for the first time in the country’s history, converged towards the common goal of opposing the nuclear option, and thus also de facto connected Portugal with the broader scenario of anti-nuclear and environmental mobilisation in western countries.1 1 This article draws on research carried out under a project funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology: Nuclear Portugal: Physics, Technology, Medicine and Environment (1910- Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk The seventies were a decade of intense anti-nuclear power protests across Western Europe: all of them recurring to a common repertoire of mobilisation and direct action, with which the Portuguese case shows strong similarities. Leading the scene was initially France: in 1971, governmental plans to locate the first light-water reactor power plant in Bugey brought out 15,000 demonstrators, who then organized an anti-nuclear camp, a sit-in and a march to Lyon. In 1975, 400 scientists signed an anti-nuclear manifesto published by the Grupement d’information scientifique sur l’energie nucleaire 2. The French scene, however, soon turned into one of violent repression. In 1976, massive demonstrations at the Super Phoenix breeder reactor in Creys-Malville culminated in violence3, with one young demonstrator killed by a gas grenade. Following the accident, 4000 scientists signed the anti-nuclear manifesto. The same year witnessed site occupations and road blockages at Plogoff, while 20,000 people participated in peaceful demonstrations and occupations at Malville. After a strike at the La Hague reprocessing plant, even the socialist trade union CFDT took a critical position and asked for a moratorium on nuclear power4. The following year, demonstrations against a new fast breeder reactor at the Malville power plant, attended by 60,000 people, were heavily repressed by the police5. ANM starts in other countries of Western Europe approximately in the same years. In 1972, German environmentalist groups oppose plans to build nuclear plants on the French/German banks of the Rhine. After a series of peaceful occupations, in 1975 a Court action halts the construction of a power plant in Wyhl6. In 1976 and ‘77, transnational mobilisation takes place (with 10-15,000 people participating) across the Denmark/Sweden border, against the construction of the Barseback nuclear plant, located in Sweden at 20 km from Copenhagen7. Demonstrations, camping and a permanent occupation take place in 1978-79 against the projected construction of a new 2010) (PTDC/HC0063/2009), hosted by the Institute of Social Sciences of the University of Lisbon, in collaboration with CES, University of Coimbra, coordinated by Tiago Saraiva. 2 D. Rucht, ‘Campaigns, skirmishes and battles; anti-nuclear movements in the USA, France and West Germany’, Organization & Environment 4:3 (1990): 193-222. 3 D. Nelkin and M. Pollack, ‘ Political Parties and the Nuclear Energy Debate in France and Germany’, Comparative Politics Vol. 12, No. 2 (1980): 127-41 4 Rucht, ‘Campaigns, skirmishes and battles’. 5 H. Kitschelt, 'Political Opportunity Structures and Political Protest', British Journal of Political Science, vol. 16, N. 1 (1986): 57- 85; see also Rucht, ‘Campaigns, skirmishes and battles’. 6 Ibid. 7 Kitschelt, 'Political Opportunity Structures and Political Protest'. Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk reactor in Torness, Scotland8. Mass demonstrations against the nearly completed power plant of Zwentendorf took place in several Austrian cities in 19779; demonstrations against the projected construction of a new power plant took place in the same year in Capalbio and in Montalto di Castro, Italy, signalling a split of positions within the left – with a group of intellectuals launching an anti-nuclear manifesto10. Meanwhile, with a series of demonstrations against construction of power plants in Deba (1974-76) and Lemoniz (1977-82), in the Basque Country, and in Xove, Galicia (1976-77), antinuclear mobilisation takes place in Francoist Spain as well: it is strictly connected to independentism, on the one hand, and to anti-dictatorial protest on the other hand11. Many of the above mentioned construction/protest sites became the birthplaces of the environmental movements of the respective countries, while remaining important symbols of anti-nuclear mobilisation well into the 1980s and beyond: the most famous of them being Whyl in Germany, but the same could be argued for Bugey in France12, and Ferrel in Portugal. After briefly outlining the main comparative characters of ANM in western countries between the early 1970s and mid-1980s, the article will offer a detailed examination of the Portuguese case, based on an extensive exploration of archival sources and on oral history interviews.13 ANTI-NUCLEAR MOBILIZATION IN THE WEST (1970s AND 1980s): A BRIEF COMPARATIVE OUTLOOK The rise of anti-nuclear mobilisation in the 1970s can be seen as the core of a broader historical process, the emerging of a new kind of environmental consciousness and politics in the post-war era, what Donald Worster called ‘the age of ecology’. This was 8 I. Welsh, ‘Anti – Nuclear Movements: Failed Projects or Heralds of a Direct Action Milieu?’, Cardiff University, School of Social Sciences, Working Paper Series 11 (ISBN 1 872330 49 5). 9 P. Weishl ‘Austria’s no to nuclear power’, Paper in Japan (Tokyo, Kyoto and Wakayama (1988), http://homepage.univie.ac.at/peter.weish/schriften/austrias_no_to_nuclear_power.pdf 10 P. Pelizzari, ‘Socialisti e comunisti italiani di fronte alla questione energetico-nucleare 1973-1987’, Italia Contemporanea 259 (2010): 237-261. 11 R. López Romo, ‘Antinucleares y nacionalistas. Conflictividad socioambiental en el País Vasco 1y la Galicia rurales de la transición’, Historia Contemporánea 43 (2010): 749-777. 12 On Whyl see for example J.I. Engels, ‘Gender roles and German anti-nuclear protest. The women on Whyl’, in C. Berbhardt and G. Massard Guilbaud eds, Le demon moderne. La pollution dans les societies urbaines et industrielles d’Europe (Clermont-Ferrand: Presses Universitaire Blaise-Pascal, 2002); see also Rucht, ‘Campaigns, skirmishes and battles’. 13 This article is based on the analysis of news articles from national (Expresso, Diário de Notícias, Diário Popular, Diário de Lisboa, O diário) and local (O Arado, Gazeta das Caldas) newspapers, magazines (Frente Ecológica, Pela Vida, A urtiga) and books published by the environmentalist movement, legislation, debates in parliament, documents from the archive of the electrical company, and interviews with scientists, environmentalists and key figures of the local movement against the nuclear power plant. Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk based on the widespread perception of the new risks facing humanity after the development of nuclear technologies, as well as by a thorough shaking of the public trust in science and technology14. In a recent journal issue on ANM across western Europe, the US and Australia, Astrid Mignon Kirchhof and Jan-Henrich Meyer note that the 1950s and early 1960s were marked by a split in public consciousness regarding the military and civil uses of nuclear technology, the latter being largely held as a beneficial promise of cheap and abundant power. This – according to the authors – makes the emergence of anti-nuclear power mobilisation in the western world a puzzling issue, which they explain with four main reasons: 1) the spreading of open contestations, on the part of students and radical-left movements, of the politics of unlimited economic growth, with its correlated needs for an ever expanding energy supply, as a feature that strongly distinguished the new environmentalism emerged between 1968 and ‘70 ; 2) the opportunity that anti-nuclear protest offered to different strands of the counter-culture – from non-orthodox Marxism to religious and philosophical, feminist, peace, and even right-wing ecological thought – to converge on the common cause of social emancipation from centralized State and corporate power structures; 3) the emergence of dissident scientific knowledge about the low-dose effects of radiations; 4) the actual beginning of construction or enlargement of a number of power plants across Europe and the USA, which generated unexpected local protest and an unlikely convergence between rural/grassroots opposition and urban/national ecologist groups and the (inter)national ‘public opinion’15. Despite the historical importance of ANM in the rise of environmentalism in Western Europe, only recently has the issue received an increasing attention on the part of environmental historians16. It is political scientists that have mostly occupied the scene of ANM studies since the early 1980s, turning it into a paradigm case for New Social Movement theory. Developed in the course of three decades, that body of 14 Donald Worster, Nature's Economy: A History of Ecological Ideas (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1977) 15 A.M. Kirchhof and J-H. Meyer, ‘Global Protest against Nuclear Power. Transfer and Transnational Exchange in the 1970s and 1980s’, Historical Social Research vol. 39, n.1 (2014): 165-90. 16 A search on the programmes of past ESEH conferences shows only 1 result for 2003 and 2 results for 2011, whereas in 2013 there were three panels entirely devoted to ANM in Europe with 3 paper presentations each. See: http://eseh.org/event/events-archive/. A search of the E&H journal with the word ‘nuclear’ in article’s title gives no results for the European context. Also noteworthy seems the fact that, in a recent collection of essays on the history of environmentalism worldwide, the chapter on ANM in Europe is authored by a political scientist: see H.A. van der Heijden, ‘The great fear. European environmentalism in the atomic age’, in M. Arrmiero and L.F. Sedrez eds, A History of Environmentalism. Local Struggles, Global Histories, (London: Bloomsbury Press, 2014). Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk literature offers important insights for a comparative environmental history of ANM in Europe17. It shows how, during the 1970s, anti-nuclear movements were capable of challenging more established nature-protection groups, setting a new model of interconnection between local grassroots struggles and broader ecological concerns, one that greatly contributed to the building of stronger and politically more capable environmental movements and new political formations – the Green parties18. Generally speaking, political scientists have tended to represent ANM and environmentalism as a manifestation of the increased importance of post-materialist values, an effect of the unprecedented economic growth and democracy enjoyed by Western Europe in the preceding period19. In this approach, a sharp distinction is posited between ‘materialist values’, i.e. those associated with economic issues such as employment and social welfare – typically held by low-income populations posited on the opposite front with respect to ‘green’ politics – and ‘post-materialist values’, i.e. those associated with life quality and the protection of endangered species – representative of higher-income populations. Some authors allow for a more nuanced view, noting that environmentalism also encompasses materialist values such as the protection of natural resources and of human health against development projects based on life-threatening technologies20. Since the early 1990s, moreover, the existence of any substantial difference between environmental concerns in rich and poor countries has been heavily contested21. In addition, it should be noted that the distinction does not easily apply to ANM and environmentalism occurring in peripheral areas of Europe with mostly agrarian economies and authoritarian or post-authoritarian regimes, as in the case of Greece, Spain and Portugal. Other factors must be drawn into the analysis in order to understand the rise of environmental mobilization in these countries. Based on both the available literature and on new empirical evidence, our detailed analysis of the 17 For a recent review of the political science literature on ANM in Western Europe, see H.A. van der Heijden, ‘The Great Fear’. 18 See for example Dick Richardson and Chris Rootes, The Green Challenge: The Development of Green Parties in Europe (London: Routledge 2006). For the German case, see: William Markham, Environmental Organizations in Modern Germany: Hardy Survivors in the Twentieth Century and Beyond (New York: Berghahn Books, 2013). 19 See van der Hejiden, ‘The great fear’. 20 See for instance Richardson and Rootes, The Green Challenge. 21 See J. Martínez-Alier, "The environment as a luxury good or "too poor to be green"?" Ecological Economics, 13: 1-10. See also R.E. Dunlap, K.D. Van Liere, A.G. Mertig, R.E. Jones, "New Trends in Measuring Environmental Attitudes: Measuring Endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm: A Revised NEP Scale." Journal of Social Issues 56 (2000): 425-42. Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk Portuguese case is intended to help revise long-held distinctions between rich and poor, materialist and non-materialist types of environmentalism, seeing them from a southern Europe perspective. Environmental mobilization in Portugal: the state of the art While Portugal is missing from the Anglophone comparative literature on ANM in Western Europe, it is included in studies on environmental mobilization in Southern Europe developed in late 1990s: we can thus take these as a good starting point for our investigation. In her quantitative comparative study of Greece, Spain and Portugal between the late 1970s and late 1990s, Maria Kousis found that these were characterized by ‘the rising importance of smaller but strong coalitions of mobilizers from urban and rural communities’, based on activist groups that ‘are autonomous and community-based, making claims that are focused on a deeply intertwined set of ecosystem, health, and economy issues’. She found that these groups mobilized ‘more often against nuclear waste, nuclear energy, agricultural infrastructure projects, and the lack of ecosystem protection in undeveloped areas’, and that ‘their claims challenge life-threatening sources or (in)activities’. These cross-regional, urban-rural coalitions – she found ‘seek assistance from the widest variety of bodies or agencies. Yet they also target a wide range of challenged groups’.22 Despite a weakness in formal associational culture, common to the three countries, could have misled scholars to believe that environmentalism was absent or socially insignificant, Kousis concluded, ‘strong community and resistance cultures’ existed which invited to not identify the environmental movement – sic et simpliciter – with formal environmental NGOs. Rather, environmental mobilization was the result of a myriad of non-institutionalized grassroots resistance actions targeting ‘powerful groups in a very direct and confrontational manner about serious problems which have immediate effects on the activists and their communities’. This was evaluated as a successful strategy: evidence from all three countries showed that ‘when links are made 22 M. Kousis, ‘Environmental protest cases: the city, the countryside, and the grassroots in southern Europe’, Mobilisation: An International Journal, 4:2 (1999): 223-38. Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk from the local level to the global, and vice versa, then there is more hope for effective environmental protection’.23 This South-European pattern of environmental mobilization may be explained as related to the commonalities in post-war politics among the three countries – i.e. authoritarian and post-authoritarian regimes – that heightened the level of social conflict and the radical oppositional character of environmental protests. In the Portuguese case, this scenario was at its peak soon after the 1974 revolution which abolished Salazar’s regime, and revolved around the Ferrel protest, commonly reputed as the ‘first environmental conflict of the democracy era’24. According to E. Figueiredo, T. Fidélis and A. Pires, the first two years of the post-dictatorship period (1974-76) had seen the sudden rise of a number of environmental groups, mostly of local reach, which suffered from weak organizational capacity and struggled to get their message heard in the Portuguese society at large. Things changed with the Ferrel protest, which marked the beginning of a new era for Portuguese environmentalists. Based on the analysis of surveys conducted between the late 1980s and late 1990s, this study concluded that the environmental attitudes of Portuguese people tended to be oriented by materialist values, which could be related to the socio-economic context and to the rural distribution of large part of the population: water sanitation and sewage and waste treatment were still considered environmental priorities by the majority of Portuguese people. Post-materialist values, however, such as participation in public decisionmaking, also played an important role25. In his analysis of environmental politics in Portugal, Gil Nave concluded that environmental mobilisation between the mid-1970s and mid-1980s had substantially coincided with the nuclear issue, where ‘a weakly organized, though convincing, discourse-oriented action that strongly mobilized public opinion’ succeeded to halt ‘the powerful public energy planning sector’. In the Portuguese nuclear power debate, he wrote, ‘what was at stake was the legitimacy of decision-making processes centred on 23 Ibid. More recent research, moreover, has confirmed that ‘civil society in Greece, Italy, and Spain appears to be much stronger on environmental matters than anticipated’: see M. Kousis, D. Della Porta and M. Jimenez, ‘Southern European Environmental Movements in Comparative Perspective’, American Behavioral Scientist, Vol. 51 Nr. 11 (2008): 1627-47 24 L. Schmidt, ‘Ambiente e políticas ambientais: escalas e desajustes’, in Villaverde-Cabral, M.,Wall, K., Aboim, S. e Carreira da Silva, Filipe (eds), Itinerários. A investigação nos 25 anos do ICS. Lisboa: Imprensa de Ciências Sociais, 2008, 285-314; see also E. Figueiredo, T. Fidélis and A.R. Pires, ‘Grassroots Environmental Action in Portugal (1974-1994)’, in K. Eder and M. Kousis (eds), Environmental Politics In Southern Europe. Actors, Institutions and Discourses in a Europeanizing Society (Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media, 2002). 25 Figueiredo et al, ‘Grassroots environmental mobilization in Portugal’. Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk the mechanisms of representative democracy and administrative technocracy’. In other words, Ferrel and the ANM represented a strongly political case for the right to public participation in decision-making processes after four decades of authoritarian regime. This political meaning of the struggle, he adds, lost importance once the consolidation of democratic institutions in the following years 'gave rise to new forms of public debate', based on expert knowledge more than on mass mobilization. At that point, ‘other powerful and highly influential actors emerged defending a non-nuclear solution’, such as groups of dissident scientists as well as ‘influential leaders of conventional parties and of several governments’ (including a significant strand of ecological critique led by the monarchist party), and ‘an elite of intellectuals and media opinion-makers’26. Subsequent studies on environmental controversies in Portugal have revealed long-term trends in the national political-economic scenario that need to be taken into account when considering the Ferrel/anti-nuclear case, namely the ability of Portuguese governments to push forward their plans even against strong opposition from grassroots movements and environmental NGOs.27 This trend can be seen as originating in what M.E. Gonçalves calls a ‘traditional administrative practice, which is most typically centralised, hierarchized and secretive’, little used to taking into account scientific advice and/or civil society’s views.28 Indeed, as we shall see in the next section, the historical evidence shows that it was structural constraints, more than grassroots mobilization, that ran against the nuclear option: first, the seismic character of the Ferrel region, which led to its abandonment as a possible plant site in 1981; second, and perhaps more importantly, the serious financial restrictions that prevented all subsequent governments to pursue their nuclear plans, and led to their final demise in 1986. 26 G. Nave, 'Non-Governmental Groups and the State. Environmental Politics in Portugal', in Eder and Kousis, Environmental Politics in Southern Europe. 27 See for instance the case of the incineration of hazardous industrial waste in cement factories in the 1990s and 2000s: Marisa Matias, ‘Dont Treat us Like Dirt’: The Fight Against the Co-incineration of Dangerous Industrial Waste in the Outskirts of Coimbra. South European Society and Politics, vol. 9, no. 2 (2004): 132–158; Maria Eduarda Gonçalves and Ana Delicado, ‘The politics of risk in contemporary Portugal: tensions in the consolidation of science–policy relations’, Science and Public Policy, vol. 36, no. 3 (2009): 229–239; Helena Mateus Jerónimo and José Luís Garcia, ‘Risks, alternative knowledge strategies and democratic legitimacy: the conflict over co-incineration of hazardous industrial waste in Portugal’, Journal of Risk Research, vol. 14, no. 8 (2011): 951–967. 28 Maria Eduarda Gonçalves, ‘Implementation of EIA directives in Portugal How changes in civic culture are challenging political and administrative practice’, Environmental Impact Assessment Review 22 (2002): 249–269. Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk Despite its limited impact on energy policies, and despite its being only one of many environmental protests taking place in the country in the mid to late 1970s, Ferrel remains in collective memory the origin story of Portuguese environmentalism. A recent survey on environmental conflicts in the country found that Ferrel is still reputed the number one case, as forty selected ‘experts’ ranked it first in importance among a pool of thirty-six major protest cases recorded between 1974 and 201429. How should we make sense of this long-term perception on the centrality of ANM in Portuguese environmentalism, and what does this tell us on the history of environmental mobilization in the country? It is now time to turn to a detailed examination of the case. ANTINUCLEAR MOBILIZATION IN PORTUGAL (1976-1986) The antecedents The resistance against the nuclear power plant in Ferrel has precedents in other instances of grassroots environmental mobilisation, some of which have come to have a direct participation in the case under study. The first recorded event of popular protest against environmental threats occurred in 1924, when the population of Águeda, Rios and Frasqueiros held a protest against the pollution of the river Sardão caused by copper mining at Talhadas.30 In 1957, after the death of a miller, the population living on the banks of river Alviela signed a petition and sent it to the President of the Town Council, protesting against the pollution caused by the tanneries. This local struggle assumed a national relevance because it gave rise to an Anti-Pollution Fight Committee - Popular Ecological Association (CLAPA), the first environmental grassroots movement in Portugal.31 Another case of grassroots protest happened in 1971, when a malfunction in the sulphuric acid factory in Barreiro caused a cloud of yellow smoke and 134 persons had to seek medical assistance. The population then organized a petition, first to the 29 The survey was conducted within the research project "Portugal: Ambiente em Movimento"- a cooperation between the Ecology and Society Lab of the Center for Social Studies in Coimbra (Ecosoc/CES), the Center for Mineral Technology of the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, Brazil (CETEM/MCTI), and the Center for Research in Economic and Organizational Sociology of the University of Lisbon (SOCIUS/ISEG). The 16 cases that were reputed more relevant are now published on an online map of environmental conflicts in Portugal and can be visited at http://ejatlas.org/featured/portugal. 30 O Século, 30 Jun.1924. 31 Afonso Cautela, Ecologia e luta de classes em Portugal. Reportagens (Lisboa. Socicultur, 1977); Luís Humberto Teixeira, Verdes anos: história do ecologismo em Portugal (1947-2011) (Lisbon, Esfera do Caos, 2011). Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk local authorities, then to the Ministry of Health.32 Nevertheless, environmental protests were strongly discouraged by the repression of the political police under the authoritarian regime that lasted between 1926 and 1974.33 The first Portuguese environmental NGO, the Liga para a Proteção da Natureza (Environmental Protection League), had been created in 1948, but its membership base was almost entirely limited to academics. Until the revolution of 25 April 1974, grassroots protesters thus had no organized environmental movements to turn to for support. Plans for building a nuclear power plant in Portugal also far predate the events in Ferrel in 1976: before the creation of the Nuclear Energy Board (JEN) in 1954, the government had already started funding the training of nuclear researchers, through the Nuclear Energy Study Committee at the Institute of Higher Culture (CEEN/IAC); in 1961 the National Laboratory of Nuclear Physics and Engineering (LFEN) was created, with a mandate for developing research and training future plant workers. In 1968 the government commissioned JEN to make a series of studies for preparing the implementation of a nuclear power plant and dozens of reports were produced. Legal diplomas published in 1969 (DL n. 49398) and 1972 (DL n. 487/72) established the requirements for demanding a preliminary license for a nuclear power plant. The revolution may have put the government’s plans on hold, but only for a short period. The studies continued to be conducted by JEN and by the national electrical company (CNE, which later changed its name to EDP). In November 1974 at the 1st Meeting of the Portuguese Ecological Movement (MEP) – a new organization, led by the journalist and activist Afonso Cautela, that was formed right after the revolution – a campaign in favour of a nuclear moratorium in Portugal was launched; in March of the following year a petition was started, in favour of a national debate on the nuclear option, which gathered 500 signatures.34 This and other emerging environmental groups started publishing translations of anti-nuclear French books and pamphlets (e.g. Pierre Pizon’s Atom and history in 197535). In December 1975, CNE filed the report concerning the preliminary studies of the Nuclear Power Plant, a necessary step in obtaining the construction license and the 32 Luísa Schmidt and Francisco Manso, Portugal, um Retrato Ambiental, (RTP videos, Ed FILMS4YOU, 2011) 33 K. Hamann & P. C. Manuel ‘Regime Changes and Civil Society in Twentieth-Century Portugal, South European Society and Politics, 4:1 (1999), 71-96. 34 Afonso Cautela, ‘Estratégia ecológica contra centrais nucleares’, Expresso, 13 Apr. 1976. 35 Pierre Pizon, L’atome et l’histoire (Paris: Protection contre les rayonnements ionisants revue bimestrielle, 1973) Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk first time an actual location is mentioned: Ferrel, a coastal village of 1,886 inhabitants 100km north of Lisbon.36 The local controversy hatches At first, the debate was circumscribed mainly to scientific and political circles: in November 1975 and again in March 1976, the electric company organized meetings on energy policy in which the nuclear option was discussed and some scientists (in particular Delgado Domingos, a physicist from the Lisbon Instituto Superior Técnico Higher Technical Institute) and MEP raised their objections.37 The issue of the Ferrel nuclear power plant began to be mentioned in the national newspapers in February and March 1976, when the Council of Ministers mandated EDP to have the preparatory studies finished by October, in order to start commissioning its construction to foreign contractors, and the issue was for the first time discussed in Parliament (on solicitation from a representative of the Socialist Party)38. The Comissão Nacional do Ambiente (National Environmental Committee), a government advisory board created in 1971, did not issue a formal statement on the nuclear issue, but its president wrote an opinion piece in the newspaper Expresso,39 in which he complained that the environmental bodies had not been consulted, and criticised the project on five bases: the need to explore alternative energy sources, the problem of radioactive waste, the need to import uranium, the risks of accidents, the issue of thermal and radioactive pollution. Construction works started at Ferrel in this period. Though the actual facilities under construction were just a meteorological station, it attracted the ire of the population, who had not been at all informed or consulted regarding the nuclear power station. Silvino João, at the time a young man just returned from the colonial war in Africa (he was the head of the parish council in 2013), describes how the population started to mobilise We were all wondering what was going on at Moinho Velho, they were digging big holes and nobody told us anything. We went the mayor and he told us he knew 36 Afonso Cautela, O suicídio nuclear português (Lisboa: Socicultur, 1977). Ibid. 38 A member of parliament makes a request for further clarification to the Minister for Industry and to the Secretary of State for Environment, which receives an answer only in April. See: Transcription of the parliamentary debate of 2 Apr. 1976, Parliament Diary, 21 Apr. 1976; see also: ‘Projecto de central nuclear provoca contestação‘, Expresso, 6 Mar.1976 39 Correia da Cunha, ’Um brinquedo perigoso que exige um estudo exaustivo‘, Expresso, 13 Mar. 1976 37 Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk just as much as us, he knew nothing. We had to make a stand, we had to know what was going on. (…) We had a meeting with the board of ‘Casa do Povo’ [a local corporative organisation], that was perhaps the most democratic organisation here, even though it was founded during the dictatorship, and they also weren’t informed. We started threatening the national authorities that if they didn’t tell was what was happening we would tear down the constructions.40 Though Ferrel was mainly a rural community of fishermen and farmers, some members of the younger generations were already studying in Lisbon and in contact with environmental activists, so they were able to pass on the information of what was being built and the risks it entailed. Such is the case of António José Correia, then a student of economics and the editor of a local handcrafted newspaper, O Arado, who had been in meetings with Afonso Cautela. At a certain point we received information that that was to be a nuclear power station. I had a friend called Afonso Cautela who was very important. I used to meet him at his house (…) He had this organisation that was the Portuguese Ecological Movement, whose head office was at the Avenida da Liberdade [Lisbon], it might have been an [illegally] occupied building, I don’t know. That’s where we got our information from. I can read better in French, so I went there to get some papers and magazines, things that he had there, it was the internet of that time, my Google. So I translated these texts, the main information we had to convey to the people. We adapted stickers, in blue, with the sun and a power station, saying ‘je ne fume, mais je tue’ – I don’t smoke but I kill’. I translated it into Portuguese41 O Arado was used to disseminate information about the risks of nuclear power among the population. Silvino João was in touch with José Luís Almeida e Silva, a journalist at the Gazeta das Caldas (a local newspaper in the nearby city of Caldas da Rainha), who 40 41 Interview with S. João, 2013 Interview with A. J. Correia, 2013 Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk also made leaflets and posters alerting to the nuclear risk and had them displayed in local cafés.42 On 5 March, the local Comissão de Moradores (Residents’ Committee) (one of thousands that had been formed across the country in the revolution’s aftermath)43 sent telegrams to several national and regional authorities (among which the Prime Minister and the Ministry of Industry, EDP) to protest against the plant constructions and announce the decision to oppose it. Despite receiving copies of the telegrams, the media paid very little attention to the issue: no articles were found in either quality or popular newspapers. Ten days later, having received no reply, a meeting of the Residents’ Committee was held, in which it was decided to take direct action. In the morning of 15 March 1976, roused by the tolling of the bells, the population of Ferrel gathered in the village churchyard and marched to the construction site, evicting the builders and destroying the incipient foundations of the meteorological station. The population issued then a statement, declaring their intention of repelling any attempts to resume the construction works and setting up Comissão de Apoio à Luta Contra a Ameaça Nuclear (Committee for Supporting the Fight against the Nuclear Threat) (CALCAN).44 This statement describes the main arguments that were invoked to justify the decision: the disadvantages of such construction, in particular the pollution of the environment, with serious dangers for health (increase in cancer, etc.), death of marine species (algae and fishes), thus affecting important agricultural and fishing activities, the increase in the economic and political dependency of our country with regard to the country that is selling the power plant and that will 42 ‘Os 36 anos do levantamento de Ferrel contra o Nuclear foram assinalados em Peniche’, Gazeta das Caldas, 5 Apr. 2012. 43 C. Downs, ‘Comissões de moradores and urban struggles in revolutionary Portugal’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 4, no. 2 (1980), 267-294; P. R. Pinto, ‘Urban social movements and the transition to democracy in Portugal, 1974–1976’, The Historical Journal, vol. 51, no 4 (2008), 1025-46; T. Fernandes, ‘Rethinking pathways to democracy: civil society in Portugal and Spain, 1960s–2000s, Democratization 22:6 (2015), 1074-1104 44 Cautela, O suicídio nuclear; Teixeira, Verdes anos; A. Moniz, ’Peniche: da produção de peixe à produção de lixo radioactivo‘, Raíz e Utopia nº 2 (1977): 159-165 Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk prepare the uranium for its functioning, are far superior to the advantages it may bring45 Environmental, public health and economic considerations at the local level were combined with global economic and geopolitical ones, stemming conceivably from political alignments. This fact prevents possible readings of the Ferrel uprising as a NIMBY case: the protesters did not want nuclear power plants in anyone’s backyard, not just their own. The country mentioned in the statement was West Germany, but the United States, with its ‘atoms for peace’ policy, had supported much of the research endeavours in the past decades in Portugal. As for the political implications, Residents’ Committees were often associated with communist and other left-wing parties46, and in fact A. J. Correia was later elected mayor of Peniche with support from the communist party. However, there was never a clear-cut political division around nuclear energy in Portugal. The nuclear option had been strongly pushed forth by the left-wing provisional government, appointed after the revolution, and a socialist government, elected in June 1976, continued to work towards the construction of the nuclear power plant. In the following years, socialists and conservatives alternated in power (sometimes even in coalition with each other) without noticeable changes in energy policy. The anti-nuclear stance was first taken to Parliament by a member of the socialist party, but one of the most outspoken opponents of nuclear energy was a member of parliament elected by the monarchic party, which became part of the conservative government coalition that ruled the country between 1980 and 1983. The communists also had an ambivalent position: they opposed the nuclear power plant because it was not bought from the Soviet Union. That much is clear in a debate in 1977, in which a parliamentarian labelled the proposed power plant as ‘an option dictated by imperialism’, imposed by a foreign ‘nuclear industry dominated by powerful monopolies’. Without rejecting nuclear energy per se, the Member of Parliament proposed a construction of a pilot nuclear power plant and the training of necessary personnel in ‘socialist countries more evolved in the field of nuclear energy’. Also, several scientists that manifested their opposition to the nuclear 45 CALCAN Statement, 15/03/1976, author’s translation. Source: http://www.cmpeniche.pt/News/newsdetail.aspx?news=f5165cc1-f135-4dc3-aff7-0323e68ab207 (last accessed 22 September 2015) 46 M. Lisi, ‘O PCP e o processo de mobilização entre 1974 e 1976’, Análise Social XLII(182) (2007):181–205. Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk power plant were affiliated to the communist party. News coverage in national newspapers affiliated with the communist party also show that, though the latter supported the popular movement in Ferrel47;48), its stance was not against nuclear energy as such (a few weeks previously Diário had published an article lauding the achievements of the Russian nuclear industry)49 but rather against a Western block sponsored nuclear power plant instead of a Russian one.50 Conversely, in mainstream newspapers, the events in Ferrel went fairly unreported. Though the nuclear debate received a fair amount of exposure, it was limited to the controversy among political and scientific elites. CALCAN persisted in trying to be recognised as a legitimate stakeholder in the decision making process, but to no avail. It issued other statements, claiming the need to involve the public in the decisions and denouncing the risks of nuclear energy, using examples from Germany and the Netherlands.51 Another telegram to the Prime Minister was sent, this time signed also by several residents’ committees, local civil society organizations, the canned fish and fishermen’s trade unions, and the local technical school.52 The mayor announced that meetings would be held across the municipality to discuss the nuclear issue. A debate took place in a nearby town, organized by the local newspaper Gazeta das Caldas, with two officials from JEN, one representative from the Residents’ Committee of Ferrel and Afonso Cautela. In the following months several other debates were organized locally, with the participation of scientists (Delgado Domingos, Carlos Matos Ferreira) and environmental activists from Lisbon and other parts of the country. Conversely, scientific debates organized in Lisbon, such as the 2nd National Meeting on Energy Policy (March 1977), included the participation of representatives from the local community of Ferrel. Two petitions, demanding an open public debate on the nuclear power plant and a thorough discussion in Parliament, were launched locally, but the Prime Minister refused to receive a delegation of residents.53 Government officials also failed to attend any of the local meetings. 47 ‘Nuclear power plant threatens fishing’, ‘Ferrel population calls off nuclear power plant’, ‘Peniche council rejects nuclear plant’ For negotiators of the power plant: tourism is more important that the people’s health: Headlines in Diário 15th March, 16th March, 18th March and 20th April 1976 48 ‘In Ferrel the bells tolled calling out to the fight against the nuclear dragon’ Headline, Diário Popular 23rd January 1978 49 Diário Popular, 1st March 1976 50 ‘Energy: is Portugal being governed from Washington? World Bank imposes rise in tariffs. Nuclear power plant: an obscure deal’ Headline in Diário, 27 March 1976. 51 Moniz, ‘Peniche: da produção de peixe’ 52 Cautela , O suicídio nuclear;Teixeira , Verdes anos… 53 Moniz (1977), Peniche: da produção de peixe Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk In order to appease the local protest, in April 1976 the Minister of Industry announced that JEN and EDP would conduct an ‘enlightenment campaign’ regarding the safety of nuclear power plants, appointing a ‘Coordination Committee for Informing the Public on Nuclear Issues’ in September of the same year (despacho n. 124/76, 9 September 1976). Besides holding some sessions for the media, this Committee prepared a booklet aimed at the population of Ferrel explaining the choice of the location. The booklet ‘Site studies for the nuclear power plant’54 was remarkably patronizing (filled with colourful childish drawings – see Figure 1 and 2) and dismissed all risks as manageable through safety regulations, but it was never distributed. However, JEN did publish in 1977 a series of brochures on nuclear energy,55 also rich on images, containing a tranquillizing message. Figure 1 Illustration of the location of the nuclear power plant Source: booklet ‘Site studies for the nuclear power plant’, EDP, 1976, p. 8 Figure 2 Illustration of natural and artificial radiation risks 54 Archive of the electrical company, reference I12.03.03-07. Jaime Manuel da Costa Oliveira and Eduardo J. C Martinho, Energia nuclear: origem e aplicações (Lisboa: Junta de Energia Nuclear, 1978). 55 Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk Source: booklet ‘Site studies for the nuclear power plant’, EDP, 1976, p. 13. Aiming at pacifying political and scientific opponents, the government declared in August 1976 that a Livro Branco do Programa Nuclear (White Book on the Nuclear Program) would be prepared, but the committee in charge of its drafting, led by a researcher from LFEN and composed by other scientists and engineers from the same institution and EDP, was only appointed in December. This committee revised the scientific literature and reports and conducted auditions with several parties, pro and against nuclear. Its conclusions were ambiguous: albeit in favour of nuclear energy, the report concluded that ‘in light of the available data, it would not go amiss to postpone the decision about the immediate setting up of nuclear power plants’.56 However, despite being submitted to the government in December 1977 and even published in book form in 1978, the report was only publicly disseminated in June 1980. Meanwhile, the anti-nuclear movement gained momentum. Though the focus was still Ferrel, the local population played a gradually diminishing role, whereas environmental activists, supported by sympathetic scientists, became the driving force of the protest. In February 1977 an environmental magazine named Viver é Preciso (To Live is Necessary) published a manifesto against the government’s pro-nuclear stance, significantly entitled ‘We are all people of Ferrel’. In June a forum was held in Caldas da Rainha, where motions for a ‘Moratorium for the Portuguese Nuclear Program’ and a ‘Popular Creative Intervention in Defence of a non-depleted environment’ were 56 Ministério da Indústria e Tecnologia, Centrais nucleares em Portugal: projecto de livro branco (Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda, 1978) Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk presented. A few months later the local newspaper started publishing a supplement called ‘Pela Vida’ (‘For Life’), addressing environmental and energy issues. The crowning moment of this movement occurred in January, again at Caldas da Rainha: the two-day Festival ‘Pela Vida e Contra o Nuclear’ (‘For life and against nuclear’) brought together close to 3,000 participants. The Festival comprised debates, workshops, exhibitions, performing arts and music shows and several other activities,57 in what Luisa Schmidt characterizes as ‘fitting to the ‘demo-festive’ [a witticism joining the words demonstration and party] climate of the period’.58 Scientists, artists, environmentalists (including the above mentioned CLAPA and some activists from Spain), and the Residents’ Committee of Ferrel took centre stage. The festival celebrated the 1976 Ferrel uprising with a march to the power plant site, where potatoes were planted to symbolize the victory of agriculture over hazardous energy generation. At this point, non-local activists (mostly from Lisbon) already outnumbered the local population. Moreover, some of the leading figures of the 1976 events declined the invitation to participate: I had already done my work. I didn’t go to that [march], I can explain why. I felt the veracity of the population march. To me that was the real thing. Since I had been there, at the real thing, it’s not really my character to follow in the heard. I don’t like crowds. I don’t know who’s coming with me and for what reasons59 Again, these events received very little coverage from national media.60 The few newspaper articles published on that year concerned only the delays on the publication of the Livro Branco. Afonso Cautela called the Festival the ‘unifying current’ of the ecological community, although he also acknowledged that it fizzled out after the event and the movement was emptied out.61 But the centrality of the nuclear mobilization for the Portuguese environmental movement can be easily discerned by searching through the 57 Associação Portuguesa de Ecologia Amigos da Terra, Antes... durante... e depois de Chernobyl: o nuclear no mundo e em Portugal, (Lisboa, A.P.E., 1987) 58 L. Schmidt. ’Ambiente e políticas ambientais: escalas e desajustes’, in M. V. Cabral et al. (eds.) Itinerários: a investigação nos 25 anos do ICS, pp. 285–314 (Lisboa: Imprensa de Ciências Sociais, 2008). 59 Interview with A. J. Correia, 2013 60 An exception was the article published in Diário Popular ‘Party against the nuclear danger’ 23rd January 1978 61 ‘Antinuclear: uma internacional pela vida’, A urtiga, September/October 1978. Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk publications of environmental organisations (magazines and books)62 of the time: throughout the second half of the 1970s dozens of articles were published on the nuclear issue, giving particular attention to anti-nuclear movements across Western Europe. Although the presence of foreign activists in Portugal was scarce during the protests, some sent support letters, which were published in the environmental movement magazines. Several of the Portuguese environmentalists and scientists that led the protests had lived abroad, mainly in France, where they had come into contact with the anti-nuclear movement. I went to France in 1969 to avoid the draft for the colonial war. I didn’t agree with the colonial politics. (…) I went on a scholarship to study French literature (…) I used to read a satirical newspaper, Charlie Hebdo, (…) that had a column about environmental issues, I knew nothing about this at the time, from a civic and public but also philosophical perspective. (…) The opinion column was very combative, it was written by Pierre Fournier (…) who later founded ‘La Gueule Ouverte’ , due to the need to create an autonomous space focused on ecological issues. (…) The antinuclear fight started in France with that magazine (…) I started to think about that paradigm, started questioning my previous thoughts and opened a new line of reflection and thought63 Therefore, the impact of the anti-nuclear international movement over the national one cannot be disregarded, even though the Portuguese television (constrained by political censorship) had not broadcasted any coverage of the international anti-nuclear movements of the 1950s and 1960s64. The anti-nuclear movement in Portugal adopted much of the same imagery of protests elsewhere, e.g. the symbol of the red smiling sun, against a yellow backdrop, surrounded by the slogan ‘Nuclear power? No thanks’. However, the movement also created its own iconography, used in posters, stickers and as illustration of magazine articles, deploying natural elements (animals, trees) to symbolise the opposition to nuclear, death symbols (graveyards, skeletons) to represent nuclear energy and national references (map of the country, local political figures) to embed antinuclear struggle in the Portuguese context (Figures 3 to 5). 62 A urtiga, Frente Ecológica, suplemento ‘Pela Vida’, Cautela O suicídio nuclear Interview with José Carlos Marques, 2013 64 Luisa Schmidt, Ambiente no ecrã: emissões e demissões no serviço público televisivo, (Lisboa, Imprensa de Ciências Sociais, 2003), p. 301. 63 Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk Figure 3: Sticker of the Festival For Life Against Nuclear Source: Archive José Pacheco Pereira, http://ephemerajpp.com/ Figure 4: Sticker of the CALCAN group Source: Archive José Pacheco Pereira, http://ephemerajpp.com/ Figure 5: Sticker of the Portuguese Ecological Movement Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk Source: Archive José Pacheco Pereira, http://ephemerajpp.com/ Figure 6: Cartoon published in the environmental magazine A urtiga Source: A urtiga, n. 1, February 1978 As in the French case, a number of Portuguese dissident scientists became steadfast supporters of the local protest, lending credibility and legitimacy to the risk claims of citizens and environmentalists. They participated in local meetings, wrote opinion pieces for the newspapers, issued a manifesto in favour of a public debate on the nuclear option in June 1977, subscribed by over a hundred scientists and engineers (including Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk some from LFEN and EDP, a further sign that the controversy was far from clear-cut)65 and a year later formed a ‘Promoting Committee for the National Debate on the Nuclear Option’, with double the number of signatories of the manifesto. The post-revolutionary background, though, is the fundamental backdrop of the movement: it brought the newly achieved freedoms of association and public demonstrations and the surge of Residents’ Committees that helped mobilize the citizens of Ferrel. It also spurred a solidarity movement from Lisbon’s intellectual elites (scientists, journalists, environmental activists, artists) towards the plights of rural populations that were expressed through massive literacy campaigns66 and the Serviço Cívico Estudantil (Student Civic Service).67 Some of the scientists and activists that were involved in the protest had been away from the country and did not take part in the 1974 revolution, thus the anti-nuclear protest gave them the opportunity to give their contribution to the ongoing process of democratization from below. The leading cultural magazine of the time,68 Raíz e Utopia, published a roundtable titled ‘O núcleo do nuclear ou Energia nuclear, uma ilusão cara?’(‘Nuclear’s nucleus or nuclear energy: an expensive illusion?’) on its first issue, and the Manifesto on energy policy on its second issue (both in 1977). The involvement of artists – several released protest songs against nuclear power, one directly mentioning the case69, which was considered ‘almost the official anthem of Ferrel’70 – was also typical of the spirit of the time, with its strong link between art and revolution.71 Students and a professor from Porto’s Faculty of Arts painted a mural against the nuclear power plant on a house near the town square of Ferrel. Since the house was later demolished, the mural was reproduced in a tile panel and placed in the same location, in celebration of the uprising.72 65 C. M. Ferreira, ‘Por um debate nacional sobre a opção electronuclear (Manifesto sobre política energética)’, Raíz e Utopia 2 (1977), 151-158 66 S Vespeira de Almeida, A caminhada até às aldeias: A ruralidade na transição para a democracia em Portugal Etnográfica, . ‘ ’, vol. 11, no. 1 (2007):115– 139. 67 L Tiago de Oliveira ,’ Schools without walls during the Portuguese Revolution: the Student Civic Service (1974-77)’. Portuguese Journal of Social vol. (2005): 145-168; Fernandes, ‘Rethinking pathways to democracy 68 Cristiano Pinheiro da Paula Couto, ‘Raiz & Utopia: Democracia E Discurso Crítico No Pós-25 De Abril(1977-1981)’ XVIII Simpósio Nacional de História, Florianopolis, July 2015. 69 “In Ferrel, close to Peniche/they are building a power plant/that for some is nuclear/but for many is deadly/Fishes will come to your hand/One is sick, the other dead/The fisherman has no livelihood/The shad and the salmon die/’This is civilization?/do said the gentleman/Be careful”, Rosalina, Fausto, in Teixeira , Verdes anos, p. 96. 70 Interview with José Manuel Almeida Silva, 2013. 71 N. Guimarães-Costa, M.P.E Cunha, M.P.E. and J. V. da Cunha, ‘Poetry in motion: protest songwriting as strategic resource (Portugal, circa 1974)’, Culture and Organization, vol. 15, no. 1 (2009):.89–108. 72 Interview with José Manuel Almeida Silva, 2013. . Science, 4 no. 3 Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk Figure 7 Tile panel reproducing a mural painted in the 1970s Source: author’s photo, Ferrel, 2013 Closure of the case Although at the end of 1978 the first intervention from the International Monetary Fund in Portugal made abundantly clear that the financial resources for building a nuclear power plant were non-existent, the project was officially cancelled only in 1981, on the basis of seismological studies that had shown high earthquake risk at Ferrel. However, the political will to adopt nuclear energy in Portugal took a while longer to dispel. The National Energy Plans of 1982 and 1984 still envisaged the construction of nuclear power plants (against which a new petition was launched ‘by a large number of people from different sectors and left-wing sensibilities’)73 and the main right-wing party held a conference in 1984 about the nuclear option. However, the economic background was far from favourable: Portugal was forced to ask for another intervention of the International Monetary Fund in 1983. Much like what many of the antinuclear critics claimed, the country simply lacked the resources for setting up nuclear energy generation. In 1986, under a right-wing government, the Secretary of State for the 73 Schmidt (2003), Ambiente no ecrã, p. 400. Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk Environment Carlos Pimenta, a staunch defender of environmental protection, announced that the nuclear option was definitely abandoned.74 As already mentioned, the anti-nuclear movement can hardly claim that it played a significant role in the decision to call off the construction of the nuclear power plant, as successive governments failed to engage with protesters in any meaningful way, or even to recognise the need for public debate. Moreover, only half-hearted attempts at persuading the local population were made, with no intention of taking its concerns into consideration. The aftermath Even though Portugal remained nuclear energy free, it has still been exposed to risks from nuclear power plants in neighbouring Spain, some of which were built close to the border or near rivers that cross both countries. In the 1980s, the construction of the power plant of Almaraz and the plan to create nuclear waste repository in Aldeadávila de la Ribera, a village located in the Douro river basin just 4 km from the Portuguese border, motivated protests from environmental organizations and local citizens from both sides.75 As to the environmental movement, many of the small groups which were active in the anti-nuclear protest eventually disappeared. Conversely, new Environmental NonGovernmental Organizations (such as Quercus or Geota) emerged in the 1980s, with a larger support base, often lead by members of the scientific community: they became gradually recognized by the governments as legitimate partners and effective pressure groups. Celebrations for the 30th anniversary of the Ferrel uprising, in 2006, brought together old and new environmental activists, scientists, left-wing politicians and the local leaders – some of the leading figures of the protest were by now heading the local authorities of Ferrel and Peniche, having been elected the previous year. The celebration included the re-enactment of the march against the power plant, the unveiling of a commemorative plaque in the churchyard and of a panel of tiles reproducing a mural against nuclear power painted at the time of the protest (Figure 3). A fiction book 74 Teixeira, Verdes ano.; José Paiva ‘Marcos ambientais da década de 70’, in 60 anos pela natureza em Portugal (Lisboa, LPN, 2008); Inês Mansinho, and Luisa Schmidt, , ’A emergência do ambiente nas ciências sociais : análise de um inventário bibliográfico‘ Análise Social, 125-126(1-2) (1994):441–481. 75 Mansinho and Schmidt ’A emergência do ambiente’; Schmidt , Ambiente no ecrã. See also: Ejolt Atlas Portugal: http://ejatlas.org/conflict/nuclear-waste-storage-near-the-spanish-frontier-of-portugal. Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk retelling the events of 1976 was launched with the occasion76 and a new platform of ENGOs against nuclear energy was formed in response to the re-emergence of the nuclear lobby.77 Also, the mayor of Peniche signed an agreement with a renewable energy company to set up a wind farm close to the proposed location of the nuclear power plant.78 Over the coming years, the anniversary was often marked with commemorative events, such as a film festival in 2012. CONCLUSION The previous section shows how the anti-nuclear movement was indeed a foundational moment for the environmentalist community in Portugal. Mobilisation was mainly fostered by the local youth in contact with environmental activists from Lisbon, fairly well informed on the ANM across Europe. Scientists were drawn into local debates and in turn invited local activists to participate in technical discussions. Celebratory events, just as the festival in Caldas da Rainha brought together environmentalists, scientists, artists and local residents. It was this coalition of different actors that marked the difference from previous cases of environmental protest and led to labelling Ferrel as the founding moment of the environmental movement in Portugal. In addition, joining together disparate activists working in near isolation and giving them a common goal, nuclear protest laid the foundations for far more stable ENGOs. It had also helped forge links between environmentalists, scientists and other cultural elites, strengthening the foothold of environmental issues in public opinion and policy making. After Ferrel, environmental grassroots movements became increasingly more common79. From the ‘kaolin wars’ in Barqueiros80 to the protracted fight against the coincineration of hazardous industrial waste in Souselas,81 through the protests against the contamination of the river Lis with sewage from pig farms,82 there have been many instances of local populations rising against perceived environmental threats. What has changed since the 1970s is the repertoire of action available to protesters, in particular 76 Mariano Calado, A maldição das bruxas de Ferrel, (Porto, Edições Sempre em Pé, 2006). ‘População de Ferrel revive primeiro protesto antinuclear30 anos depois’, Público, 19 Mar. 2006; “Ambientalistas criam plataforma contra o nuclear”, Público, 20 Mar. 2006. 78 Later, a wave power experimental facility was set up in the sea, directly in front of the nuclear power plant site, also a project supported by the local authority. 79 Figueiredo et al, ‘Grassroots Environmental Action in Portugal (1974-1994)’.. 80 Schmidt, ‘Ambiente e políticas ambientais’ 81 Matias “Dont Treat us Like Dirt’; Gonçalves and Delicado, ‘The politics of risk’; Jerónimo e Garcia, ‘Risks, alternative knowledge strategies’. 82 J. G. Ferreira ‘Façam o milagre! Poluição, media e protesto ambiental na bacia do Lis’. In VII Congresso Português de Sociologia. (Porto, APS, 2012). 77 Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk summoning the media to report on the case (receiving much more attention than before, especially since the emergence of private TV channels)83, legal actions and injunctions in Portuguese and European courts, and complaints to European authorities. Also, European environmental laws have made public consultation mandatory in environmental impact assessments. However, authorities still seems reluctant to let local residents and ENGO concerns stand in the way of profitable projects, placing all sort of obstacles in the way of effective public participation.84 Overall, our research has found strong convergences between ANM in Portugal and in other western countries: as delineated in the literature, the protest in Ferrel adopted languages and motivations originated in the counter-culture and radical left politics of the 1960s, including radical critiques of economic growth and technocracy; it represented a convergence between different political groups, beyond the party system; it enjoyed support on the part of dissident scientists; it was originated by the starting of construction works. As in most other cases of anti-nuclear protest in the same period, also in the Portuguese case middle-class and grassroots movements can be seen as allies, rather than competitors85. However, Portuguese ANM also reveals three peculiar aspects, which should be understood against the backdrop of the country’s position at the European periphery, both in the geo-political and the economic sense: 1) a combination of materialist and post-materialist values; 2) a strong connection to revolutionary politics; 3) the relevance of financial constraints in halting the implementation of the nuclear plan. As regards the first aspect, the mostly agrarian character of the Portuguese economy of the time explains why protests emerged as a defense of ecosystem integrity and natural resources (land and fisheries) which were vital for the local economy. Such materialist values combined with those of the ecologist counterculture, with the defense of local autonomy and sovereignty and with the struggle for the democratization of public decision-making. It was such combination of different values what made possible the coalition between local and national, rural and urban levels of mobilization. 83 Figueiredo et al., ‘Grassroots Environmental Action in Portugal (1974-1994)’; Schmidt, ‘Ambiente e políticas ambientais’. 84 Chito, B. & R. Caixinhas ‘A participação do público no processo de avaliação do impacte ambiental’, Revista Critica de Ciências Sociais 36 (1993): 41–55; Lima, M.L.P. ‘Images of the public in the debates about risk: consequences for participation’, Portuguese Journal of Social Sciences 2(3) (2004): 149–163. 85 On this aspect see for example: J.A. Carmin, ‘Voluntary Associations, Professional Organisations and The Environmental Movement in the United States’. Environmental Politics, 8:1, 101-121. See also Forthcoming in Environment and History ©The White Horse Press http://www.whpress.co.uk Second, the mobilization was strongly marked by the political climate of the period, whose most important driver was the struggle over the democratization of public decision making. Although this element of the ANM is found everywhere else throughout western countries in the 1970s, it assumes a greater importance here because, unlike other western European countries, Portugal did not have wellestablished environmental organizations before the Revolution. Coinciding with ANM, Portuguese environmentalism thus assumed a radical political character as a movement for the democratization of environmental policies. In this sense, however, the Ferrel protest should be considered a lost battle, for it failed to fundamentally alter the decision-making process on energy and environmental policies in Portugal. Despite article 66 in the Portuguese Constitution (1976) recognized the “right to a healthy and ecologically balanced living environment” and the “duty to defend it”, the environmental impact of modernization policies was kept out of the governmental agenda until 1987, when a "Basic Law of the Environment" was issued as an effect of Portugal’s integration in the EU86. Finally, what strongly marks the Portuguese case is the relevance of structural constraints, and especially of extra-national financial decision-making, in determining the demise of the national nuclear power plan. 86 See Ejolt Atlas – Portugal - ‘Description’: http://ejatlas.org/featured/portugal.

![The Politics of Protest [week 3]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005229111_1-9491ac8e8d24cc184a2c9020ba192c97-300x300.png)