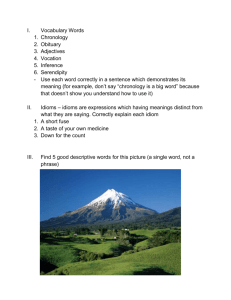

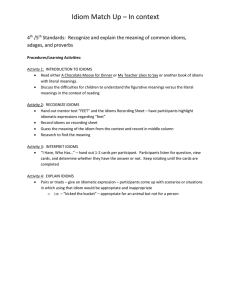

ESL Speaking Activities: Fluency, Idioms, Vocabulary

advertisement