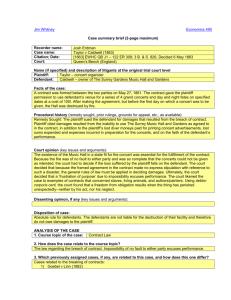

Contract Law Text, Cases, and Materials ( PDFDrive )

advertisement