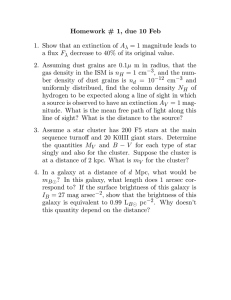

The Astrophotography Manual A Practical and Scientific Approach to Deep Space Imaging Chris Woodhouse First published 2016 by Focal Press 70 Blanchard Road, Suite 402, Burlington, MA 01803 and by Focal Press 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Focal Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2016 Chris Woodhouse The right of Chris Woodhouse to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Notices Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility. Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Woodhouse, Chris. The astrophotography manual : a practical and scientific approach to deep space imaging / Chris Woodhouse. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Astronomical photography. I. Title. QB121.W87 2015 522’.63--dc23 2014047121 ISBN: 978-1-138-77684-5 (pbk) ISBN: 978-1-138-91207-6 (hbk) ISBN: 978-1-315-77301-8 (ebk) Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro and Myriad Pro by Chris Woodhouse www.digitalastrophotography.co.uk Contents Preface About the Author Introduction 5 7 8 Astronomy Primer The Diverse Universe of Astrophotography 13 Space 16 Catalogs 23 Four Dimensions and Counting 25 Limits of Perception 30 Choosing Equipment The Ingredients of Success General Equipment Imaging Equipment Setting Up Hardware Setup Software Setup Image Capture Sensors and Exposure Focusing Autoguiding and Tracking Image Calibration and Processing Post Exposure Getting Started in PixInsight Image Calibration and Stacking Linear Image Processing Non-Linear Image Processing Narrowband Image Processing First Light Assignments Practical Examples M3 (Globular Cluster) C38 (Needle Galaxy) M51a/b (Whirlpool Galaxy) C27 (Crescent Nebula) in Narrowband M45 (Pleiades Open Cluster) M31 (Andromeda Galaxy) IC 1805 (Heart Nebula) in False Color Jupiter Appendices 39 56 70 95 111 119 127 131 149 154 162 172 182 197 Diagnostics and Problem Solving Summer Projects Templates Bibliography and Resources Glossary and Index Glossary Index 206 209 213 218 222 228 232 238 243 249 255 262 268 281 284 “Don’t Panic” Douglas Adams Preliminaries 5 Preface A s a child, I was interested in astronomy and contented myself with identifying the major constellations. It was the time of the Apollo missions and the lunar landings in the early ‘70s. In those days, amateur telescopes were a rarity and even binoculars were an indulgence for a young boy. My first book on astronomy was a Hamlyn guide. I still have it today and it is a quaint reminder of how we viewed the universe and the availability (or lack thereof) of sophisticated amateur equipment. Today, this guide is notable by its lack of photographic illustrations and belongs to the era of the technical illustrator. As a teenager, a family friend showed me the Moon and Saturn through a homemade Newtonian reflector. It wobbled on a wooden tripod and required something resembling alchemy to re-silver the 6-inch mirror that lay at its heart. I still have a black-and-white print of the Moon taken with that telescope. It is a testament to the dedication and practical necessities of early astrophotographers. In the ‘90s the seed was sown by a local astronomer who gave a slide presentation at my photographic club: It was my first glimpse of what lay beyond the sensitivities of the human eye and at a scale that completely surprised me. Those images were on Kodak Ektachrome and although I am saddened by the demise of classical photography and values, I have to concede that modern digital sensors are responsible for making astrophotography a vibrant hobby. Up until this time I was completely engrossed by photography, especially traditional fine-art monochrome. Just like the early astrophotographers, I found that necessity was the mother of invention. I designed and later patented various darkroom accessories and researched film-based photography for many years. At the same time I started technical writing: I started with a few magazine articles and progressed to full scale reference books on traditional photography. I had yet to point a camera at the night sky. Fast-forward to the present day and we are in the midst of an exponential interest in astrophotography in all its forms. Recent popular television series, Mars expeditions and the availability of affordable high-quality telescopes and cameras have propelled the fascinating world of amateur astrophotography. This surge of interest in a way mirrors the explosion of digital imaging in the prior decade, but unlike modern digital photography, astrophotography still appeals to those with a practical mind and handy skills more than those with a large bank balance, though it is safe to say, it certainly helps. In 2011, I took the plunge into the deep end. I was awestruck by what was possible, at the beauty and variety of the many images on various websites that I had previously supposed were the work of professional observatories. As I grappled with this new hobby, I found many books were out of date on digital imaging techniques and others were useful overviews but without sufficient detail in any one speciality. Thankfully, the many friendly astronomy forums were a source of inspiration and I quickly appreciated just how much there was to learn and go wrong. The other forum members and I were asking similar questions and it highlighted the need for a book that stepped through the whole process of setting up, capturing and processing images. It occurred to me I had a unique opportunity to document and share my steep learning curve and combine it with my photographic and technical skills. I have already owned several systems, in addition to using many astronomy applications for Mac OSX, Windows and Apple iOS. It is too soon to call myself an expert but it is a good time to write a book while the research and hard lessons are still fresh in my mind. During this time the constant patient support of my family has provided the opportunity for research and writing. So, in the year that Sir Patrick Moore, Bernard Lovell and Neil Armstrong passed away, I hope to inspire others with this book in some small way and improve the reader’s enjoyment of this amazing hobby through their success. The early chapters include a brief astronomy primer and a nod to those incredible early pioneers. These set you up for the technical and practical chapters and give an appreciation of achievements, past and present. The technical chapters start by looking at the practical limitations set by the environment, equipment and camera performance. After several practical chapters on the essentials, equipment choice and setting up, there are several case studies. These illustrate the unique challenges with practical details and using a range of software. An extensive index, glossary, bibliography and supporting website add to the book’s usefulness and progression to better things. Clear skies. Chris Woodhouse 2013 IC1805 (The Heart Nebula) Preliminaries 7 About the Author “The story so far: In the beginning the Universe was created. This has made a lot of people very angry and been widely regarded as a bad move.” Douglas Adams C hris was born in Brentwood, England and from his teenage years was fascinated by the natural sciences, engineering and photography, all of which he found more interesting than football. At the weekend he could be found building or designing some gadget or other. At school he used a slide-rule and log books for his exams at 16. Two years later, scientific calculators had completely displaced them. He studied Electronics at Bath University and by the time he had completed his M.Eng., the computer age was well under way and 8-bit home computers were common. After a period designing military communication and optical gauging equipment, as well as writing software in Forth, Occam, C++ and Assembler, he joined an automotive company. As a member of the Royal Photographic Society, he gained LRPS and ARPS distinctions and pursued a passion for all forms of photography, including landscape and infrared, as well as portraiture, still life and architectural photography, mostly using traditional monochrome techniques. Not surprisingly, this hobby coupled with his professional experience led him to invent and patent several highly regarded f/stop darkroom timers and meters, still sold throughout the world. During that time digital cameras evolved rapidly and photo ink-jet printers slowly overcame their initial limitations. Resisting the temptation of the early optimistic digital promises, he authored a book on traditional monochrome photography, Way Beyond Monochrome, to critical acclaim and followed with a second edition (by which time used prices had soared to over $500) to satisfy the ongoing demand. Digital monochrome appeared to be the likely next avenue for his energy until an eye-opening presentation on astrophotography renewed a dormant interest in astronomy and the possibilities that digital cameras offered. This was almost inevitable since astrophotography is the perfect fusion of science, electronics and photography. Like many before, his first attempts ended in frustration and disappointment, but he quickly realized the technical challenges of astrophotography responded well to methodical and scientific study. He found this, together with his photographic eye and decades of printing experience, were an excellent foundation to produce beautiful and fascinating images from a seemingly featureless sky. Acknowledgements This book and the accelerated learning that it demands would not have been possible without the support of my family and the generosity and contribution of the wider astrophotography community. I also need to thank Jennifer Wise for making the transatlantic crossing as painless as possible. I still claim to have a garden (with flowers) and not a back yard. It is one of the pleasures of this hobby to share problems and solutions with other hobbyists you will never likely meet. Coming from the photographic community it is refreshing to witness an overwhelming generosity of encouragement and praise to others, irrespective of their circumstances. In turn I have shared ideas and solutions with others and where possible I have tried to acknowledge those contributions that helped me on my way too. As the image of the nebula suggests, we astrophotographers are all heart! This hobby is a never-ending journey of refinement, knowledge and development. It is a collaborative affair and I welcome any feedback or suggestions for this book or the next edition. Please contact me at: chris@digitalastrophotography.co.uk 8 The Astrophotography Manual Introduction “Infinity itself looks flat and uninteresting. Looking up into the night sky is looking into infinity - distance is incomprehensible and therefore meaningless.” Douglas Adams A stronomy is such a fascinating subject that I like to think that astrophotography is more than just making pretty pictures. For my own part, I started both at the same time and I quickly realized that my knowledge of astronomy was deficient in several areas. Reading up on the subject added to my sense of awe and also made me appreciate the dedication of astronomers and their patient achievements over thousands of years. A little history and science is not amiss in such a naturally technical hobby. Incredibly, the science is anything but static; new discoveries are being made all the time and an on-going examination of the Martian surface may reveal secrets that cause us to re-evaluate extraterrestrial life. From the earliest days of human consciousness, mankind has studied the night sky and placed special significance on eclipses, comets and new appearances. With only primitive methods, they quickly realized that the position of the stars, the Moon and the Sun could tell them when to plant crops, navigate and keep the passage of time. Driven by a need for astrology as well as science, their study of the heavens and the belief of an Earth-centric universe was interwoven with religious doctrine. It took the Herculean efforts of Copernicus, Galileo and Tycho, not to mention Kepler, to wrest control from the Catholic Church in Europe and define the heliocentric solar system with elliptical orbits, anomalies and detailed stellar mapping. Astronomers in the Middle east and in south America made careful observations and, without instruments, were able to determine the solar year with incredible accuracy. The Mayans even developed a sophisticated calendar that did not require adjustment for leap years. Centuries later, the Conquistadors all but obliterated these records at a time when ironically Western Europe was struggling to align their calendars with the seasons. (Pope Gregory XIII eventually proposed the month of October be shortened by 10 days to re-align the religious and hence agricultural calendar with the solar (sidereal) year. The Catholic states complied in 1583 but others like Britain delayed until 1752, by which time the adjustment had increased to 11 days!) The invention of the telescope propelled scholarly learning, and with better and larger designs, astronomers were able to identify other celestial bodies other than Year Place Astronomy Event 2700 BC England Stonehenge, in common with other ancient archaeological sites around the world, is clearly aligned to celestial events. 2000 BC Egypt 1570 BC Babylon [Circa] First Solar and Lunar calendars First evidence of recorded periodicity of planetary motion (Jupiter) over a 21-year period. 1600 BC Germany Nebra sky disk, a Bronze age artifact, which has astronomical significance. 280 BC Greece Aristarchus suggests the Earth travels around the Sun, clearly a man before his time! 240 BC Libya Eratosthenes calculates the circumference of the earth astronomically. 125 BC Greece Hipparchus calculates length of year precisely, notes Earth’s rotational wobble. 87 BC Greece Antikythera mechanism, a clockwork planetarium showing planetary, solar and lunar events with extraordinary precision. 150 AD Egypt Ptolemy publishes Almagest; this was the astronomer’s bible for the next 1,400 years. His model is an Earth-centered universe, with planet epicycles to account for strange observed motion. 1543 AD Poland Copernicus, after many years of patient measurement, realizes the Earth is a planet too and moves around the Sun in a circular orbit. Each planet’s speed is dependent upon its distance from the Sun. 1570 AD Denmark Tycho Brahe establishes a dedicated observatory and generates first accurate star catalog to 1/60th degree. Develops complicated solar-system model combining Ptolemaic and Copernican systems. 1609 AD Germany Kepler works with Tycho Brahe’s astronomical data and develops an elliptical-path model with planet speed based on its average distance from the Sun. Designs improvement to refractor telescope using dual convex elements. 1610 AD Italy Galileo uses an early telescope to discover that several moons orbit Jupiter and Venus and have phases. He is put under house arrest by the Inquisition for supporting Kepler’s Sun-centered system to underpin his theory on tides. fig.1a An abbreviated time-line of the advances in astronomy is shown above and is continued in fig.1b. The achievements of the early astronomers is wholly remarkable, especially when one considers not only their lack of precision optical equipment but also the most basic of requirements, an accurate timekeeper. Year Preliminaries Place Astronomy Event 1654 AD Holland Christiaan Huygens devises improved method for grinding and polishing lenses, invents the pendulum clock and the achromatic eye-piece lens. 1660 AD Italy Giovanni Cassini identifies 3 moons around Saturn and the gap between the rings that bear his name. He also calculates the deformation of Venus and its rotation. 1687 AD England Isaac Newton invents the reflector telescope, calculus and defines the laws of gravity and motion including planetary motion in Principia, which remained unchallenged until 1915. 1705 AD England Edmund Halley discovers the proper motion of stars and publishes a theoretical study of comets, which accurately predicts their periods. 1781 AD England William Herschel discovers Uranus and doubles the size of our solar system. Notable astronomers Flamsteed and Lemonnier had recorded it before but had not realized it was a planet. Using his 20-foot telescope, he went on to document 2,500 nebular objects. [Circa] 1846 AD Germany Johann Galle discovers Neptune, predicted by mathematical modelling. 1850 AD Germany Kirchoff and Bunsell realize Fraunhofer lines identify elements in a hot body, leading to spectrographic analysis of stars. 1908 AD U.S.A. Edwin Hubble provides evidence that some “nebula” are made of stars and uses the term “extra-galactic nebula” or galaxies. He also realizes a galaxy’s recessional velocity increases with its distance from Earth, or “Hubble’s law”, leading to expanding universe theories. 1916 AD Germany Albert Einstein publishes his General Theory of Relativity changing the course of modern astronomy. 1930 AD U.S.A. Clyde Tombaugh discovers planet Pluto. In 2006, Pluto was stripped of its title and relegated to the Kuiper belt. 1963 AD U.S.A. Maarten Schmidt links visible object with radio source. From spectra realizes quasars are energetic receding galactic nuclei. 1992 AD U.S.A. Space probes COBE and WMAP measure cosmic microwaves and determines the exact Hubble constant and predicts the universe is 13.7 billion years old. 2012 AD U.S.A. Mars rover Curiosity lands successfully and begins exploration of planet’s surface. 2014 AD ESA Rosetta probe touches down on comet 67P after 12-year journey. fig.1b Astronomy accelerated once telescopes were in common use, although early discoveries were sometimes confused by the limitations of visual observation through small aperture devices. 9 stars, namely nebula and much later, galaxies. These discoveries completely changed our appreciation of our own significance within the universe. Even though the first lunar explorations are 40 years behind us, very few of us have looked at the heavens through a telescope and observed the faint fuzzy patches of a nebula, galaxy or the serene beauty of a star cluster. To otherwise educated people it is a revelation when they observe the colorful glow of the Orion nebula appearing on a computer screen or the fried-egg disk of the Andromeda Galaxy taken with a consumer digital camera and lens. This amazement is even more surprising when one considers the extraordinary information presented on television shows, books and on the Internet. When I have shared back-yard images with work colleagues, their reaction highlights a view that astrophotography is the domain of large isolated observatories inhabited with nocturnal Physics students. This sense of wonderment is one of the reasons why astrophotographers pursue their quarry. It reminds me of the anticipation one gets as a black and white print emerges in a tray of developer. The challenges we overcome to make an image only increase our satisfaction and the admiration of others, especially those in the know. New Technology The explosion of interest and the ability of amateurs has been fuelled by the availability of if not new then certainly applied affordable technology in mechanics, optics, computers, digital cameras and in no small way, software. Of these, the digital sensor is chiefly responsible for revolutionizing astrophotography. Knowledge is another essential ingredient and the ingenuity and shared experience through the Internet rapidly contribute to the recent advancement of amateur astrophotography. It was not that long ago that a bulky Newtonian reflector was the most popular instrument and large aperture refractors were either expensive or of poor quality. Computer control was but a distant dream. In the last few years however, Far east manufacturing techniques have lowered the cost of high-quality optical cells, mirrors and motor-driven mounts. Several U.S. companies have taken alternative folded designs, using mirror and lens combinations, and integrated them with computer-controlled mounts to make affordable, compact, high-performance systems. The same market forces have lowered the price of digital cameras and the same high-quality camera sensors power dedicated cameras, optimized with astrophotography in mind to push the performance envelope further. At the same time computers, especially laptops, continue to 10 The Astrophotography Manual reduce in price and with increased performance too, including battery life. The software required to plan, control, acquire and process images is now available from several companies at amateur and professional level and from not a few generous individuals who share their software free or for a nominal amount. At the same time, collaboration on interface standards (for instance ASCOM) reduces software development costs and lead-times. If that was not enough, in the last few years, tablet computing and advanced smart phones have provided alternative platforms for controlling mounts and can display the sky with GPS-located and gyroscopicallypointed star maps. The universe is our oyster. Scope of Choice Today’s consumer choice is overwhelming. After trying and using several types of telescope and mount, I settled on a hardware and software configuration that works as an affordable, portable solution for deep space and occasional planetary imaging. Judging from the current rate of change, it is impossible to cover all other avenues in detail without being dangerously out of date on some aspects before publishing. Broad evaluations of the more popular alternatives are to be found in this text but with a practical emphasis and a process of rationalization; in the case of my own system, to deliver quick and reliable setups to maximize those brief opportunities that the English weather permits. My setup is not esoteric and serves as a popular example of its type, ideal for explaining the principles of astrophotography. Some things will be unique to one piece of equipment or another but the principles are common. About this Book I wrote this book with the concept of being a fast track to intermediate astrophotography. This is an ambitious task and quite a challenge. Many astrophotographers start off with a conventional SLR camera and image processing software like Photoshop®. In the right conditions these provide excellent images. For those users there are a number of excellent on-line and published guides noted in the bibliography. It is not my intention to do a “me too” book, but having said that, I cannot ignore this important rung on the ladder either. The emphasis will be on the next rung up, however, and admittedly at significantly more cost. This will include the use of more sophisticated software, precision focusing, cooled CCD cameras and selective filtering. It is impossible to cover every aspect in infinite detail. Any single person is limited by time, budget and inclination. My aim is to include more detail than the otherwise excellent titles that cover the basics up to imaging with a SLR. Year Astrophotography Event [Circa] 1840 1850 1852 1858 First successful daguerreotype of Moon 1871 1875 Dry plate process on glass 1882 1883 1889 1920 1935 Spectra taken of nebula for first time 1940 Mercury vapor film treatment used to boost sensitivity of emulsion for astrophotography purposes 1970 Nitrogen gas treatment used to temporarily boost emulsion sensitivity by 10x for long exposure use 1970 Nitrogen followed by Hydrogen gas treatment used as further improvement to increase film sensitivity 1974 1989 First astrophotograph made with a digital sensor 1995 By this time, digital cameras have arguably ousted film cameras for astrophotography. 2004 Meade Instruments Corp. release affordable USB controlled imaging camera. Digital SLRs used too. 2010 Dedicated cameras for astrophotography are widespread, with cooling, combined guiders; in monochrome and color versions. Consumer digital cameras too have improved and overcome initial long exposure issues. First successful star picture First successful wet-plate process Application of photography to stellar photometry is realized Spectra taken of all bright stars First image to discover stars beyond human vision First plastic film base, nitro cellulose Cellulose acetate replaces nitro cellulose as film base Lowered temperature was found to improve film performance in astrophotography applications SBIG release ST4 dedicated astrophotography CCD camera fig.2 A time-line for some of the key events in astrophotography. It is now 30 years since the first digital astrophotograph was taken and I would argue that it is only in the last 5 years that digital astrophotography has really grown exponentially, driven by affordable hardware and software. Public awareness has increased too, fuelled by recent events in space exploration, documentaries and astrophotography competitions. To accomplish this, the book is divided into logical sections. They quickly establish the basics and become more detailed as they go on. It starts with a brief astronomy primer suitable for a newcomer or as a refresher. This sets out a basic understanding of astronomy, explains the terminology and the practical limitations set by Physics and our Earth-bound location as well as what is required for success. This subject is a magnet for specialized terms and acronyms. Getting past the terminology is an early challenge and an understanding allows one to confidently participate in forums and ask the right questions. The following section sets out the important imaging priorities and compares general and imaging-specific equipment and software. There is no one solution for all and depending on inclination, budget and location, your own ideal setup will be unique. The aim is to provide sufficient information to enable you to ask the right questions and make informed purchasing decisions. As technology advances, this section will be prone to go out of date, but on the positive side, as real costs come down, advanced technology, for example mounts fitted with digital encoders, will become more affordable. The third section is a systematic guide and explanation of a typical setup. It starts with the physical assembly and goes on in detail to describe the alignment, exposure planning and operation of the entire imaging system, with tips and tricks along the way. Unlike conventional photography, setting the correct exposure in astrophotography can be a hit and miss affair. There are many more variables at work and alternative proposals are discussed and compared. Not surprisingly, a section dedicated to image calibration and processing follows, using mainly specialized dedicated imaging applications such as PixInsight®, as well as some techniques in Photoshop. Image processing is particularly exciting in astrophotography; there are few rules and everyone has a unique trick up their sleeve. Some of these are heavyweight image processing algorithms and others a series of gradual manipulations to transform a faint fuzzy into a glowing object of beauty. Each image has its own unique challenges but most can be systematically analyzed and processed to bring out the best. This is a vast subject in its own right and there are several excellent references out there, especially using Photoshop as the main processing tool. The invention is amazing and few approaches are the same! I do my best to rationalize this in the space allowed and provide references for further reading in the bibliography and resources in the appendix. Preliminaries 11 The fifth section is made up of several case studies; each of which considers their conception, exposure and processing and an opportunity to highlight various techniques. A worked example is often a wonderful way to explain things and these case studies deliberately use a variety of equipment, techniques and software. These include Maxim DL, Nebulosity, PHD, PixInsight and Photoshop, to name a few. The subjects include lunar and planetary imaging as well as some simple and more challenging deep-sky objects. Practical examples are even more valuable if they make mistakes and we learn from them. These examples have some warts and they discuss short- and long-term remedies. On the same theme, things do not always go to plan and in the appendices before the index and resources, I have included a chapter on diagnostics, with a small gallery of errors to help with your own troubleshooting. Fixing problems can be half the fun but when they resist several reasoned attempts, a helping hand is most welcome. In my daytime job I use specialized tools for root cause analysis and I share some simple ideas to track down gremlins. Keeping on the light side and not becoming too serious is essential for astrophotography. In that vein, I found the late Douglas Adams’ numerous quotes relate to this subject rather too well and a quote graces each chapter! Astrophotography and astronomy in general lends itself to practical invention and not everything is available off the shelf. To that end, a few practical projects are included in the appendices as well as sprinkled throughout the book. The other resources in the appendices list the popular Caldwell and Messier catalogs and an indication of their season for imaging. Some of these resources lend themselves to spreadsheets, and my supporting website has downloadable versions of tables, drawings and spreadsheets as well as the inevitable errata that escape the technical edits. It can be found at www.digitalastrophotography.co.uk. References Contents “Don’t Panic” Douglas Adams 268 The Astrophotography Manual Bibliography and Resources “First we thought the PC was a calculator. Then we found out how to turn numbers into letters with ASCII – and we thought it was a typewriter. Then we discovered graphics, and we thought it was a television. With the World Wide Web, we’ve realized it’s a brochure.” Douglas Adams Bibliography Steve Richards, Making Every Photo Count, Self Published, 2011 This is a popular book that introduces digital astrophotography to the beginner. It is now in its second edition and is been updated to include modern CCD cameras. The emphasis is on using digital SLRs. Stefan Seip, Digital Astrophotography, Rockynook, 2009 This book gives a wide overview of modern techniques using a range of equipment for Astrophotography. It gives the reader a flavor for the different specialities and what can be accomplished. Robin Scagell, Stargazing with a Telescope, Philips, 2010 Robin Scagell is a seasoned astronomer and this comes through in the pages in his book. This is not an astrophotography book as such, but one that places an emphasis on general astronomy equipment as well as choosing and using telescopes. He offers many practical insights that apply equally to astrophotography. Greg Parker, Making Beautiful Deep-Sky Images, Springer, 2007 Greg takes you through the planning and execution of his observatory and equipment choices. Using a mixture of telescope types he showcases many excellent images and goes on to show how some of these are processed using Photoshop. His fast aperture system helps collect many photons and his trademark are his richly colored images. Nik Szymanek, Shooting Stars, Pole Star Publications, 2015 This Astronomy Now publication is available as a stand-alone book. Its 130 pages are filled with practical advice on imaging, and especially processing, deep sky images. Allen Hall, Getting Started: Long Exposure Astrophotography, Self Published, 2013 This is an up-to-date book which makes use of affordable equipment on a modest budget. It has an interesting section on spectroscopy and includes several practical projects for upgrading equipment and making accessories. It also features a section on imaging processing, including some of the common tools in PixInsight. Charles Bracken, The Deep-sky Imaging Primer, Self Published, 2013 This up-to-date work is focused on the essentials of image capture and processing using a mixture of digital SLRs and astronomy CCD cameras. One of its highlights are the chapters that clearly explain complex technical matters. Robert Gendler, Lessons from the Masters, Springer, 2013 It is not an exaggeration to say that this book is written by the masters. It provides an insight into specific image processing techniques, which push the boundaries of image processing and force you to re-evaluate your own efforts. Highly recommended. Heather Couper & Nigel Henbest, The Story of Astronomy, Cassell 2011 This book tells the fascinating story of the development of astronomy and is an informative and easy read. Ruben Kier, The 100 Best Astrophotography Targets, Springer, 2009 This straightforward book lists well- and lesser-known targets as they become accessible during the year. A useful resource when you wish to venture beyond the Messier catalog. Appendices Internet Resources Less Common Software (or use Internet search) Maxpilote (sequencing software) www.felopaul.com/software.htm PHD2 (guiding software) www.openphdguiding.org Focusmax (focusing utility) www.focusmax.org Nebulosity (acquisition / processing) www.stark-labs.com/nebulosity.html Sequence Generator Pro (acquisition) www.mainsequencesoftware.com PixInsight (processing)www.pixinsight.com Straton (star removal) www.zipproth.com/Straton PHDMax (dither with PHD) www.felopaul.com/phdmax.htm PHDLab (guiding analysis) www.countingoldphotons.com EQMOD (EQ6 ASCOM) www.eq-mod.sourceforge.net APT (acquisition)www.ideiki.com/astro/Default.aspx Cartes du Ciel (planetarium) www.ap-i.net/skychart/en/start C2A (planetarium)www.astrosurf.com/c2a/english Registax (video processing)www.astronomie.be/registax AutoStakkert (video processing) www.autostakkert.com Polar Drift calculator celestialwonders.com Processing Tutorials Harry’s Pixinsightwww.harrysastroshed.com PixInsight support videos www.pixinsight.com/videos PixInsight support tutorials www.pixinsight.com/tutorials PixInsight tutorialswww.deepskycolors.com/tutorials.html PixInsight DVD tutorials www.ip4ap.com/pixinsight.htm Popular Forums Stargazer’s Lounge www.stargazerslounge.com (UK) Cloudy Nightswww.cloudynights.com (US) Ice in Spacewww.iceinspace.com(AU) www.progressiveastroimaging.com Progressing Imaging Forum Astro buy and sell(regional) www.astrobuysell.com/uk PixInsightwww.pixinsight.com/forum Maxim DLwww.groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/MaxImDL/info Sequence Generator Pro www.forum.mainsequencesoftware.com FocusMaxwww.groups.yahoo.com/group/FMaxUG EQMOD (EQ mount software) www.groups.yahoo.com/group/eqmod Software Bisque (mounts/software) www.bisque.com/sc/forums 10Micron (mounts)forum.10micron.eu Weather Metcheck (UK)www.metcheck.com The Weather Channeluk.weather.com 7Timerwww.7timer.com Clear Sky Chart (N. America) www.cleardarksky.com Scope Nights (App for portable devices) eggmoonstudio.com The Astrophotography Manual Book resources and errata www.digitalastrophotography.co.uk 269 270 The Astrophotography Manual Messier Objects – suitable for imaging from London latitudes (~50°) Deep space objects are seasonal. Assuming that you need a good 4 hours or more of imaging per night, in northern latitudes, it requires low DEC objects to rise in the east and set in the west. The following table selects those Messier objects above the imaging horizon (30° altitude or more), along with the month in which they first achieve this altitude at dusk and the likely imaging time span until it sets below 30°. The items were identified by using a planetarium program, selecting nautical sunset for the middle of each month and noting which Messier objects first appeared in the east above the imaging horizon. The imaging duration is the general span of time from astronomical dusk to dawn for that calendar month. This then is the maximum imaging time available assuming the object rises above the imaging horizon as it gets dark. M NGC constellation type RA [hr] DEC [deg] mag size [arcmin] imaging visible from [hr] M82 3034 Ursa Major Galaxy 9.93 69.6833 8.4 11.2 all night all year M81 3031 Ursa Major Galaxy 9.9266 69.0666 6.9 25.7 all night all year M35 2168 Gemini Open Cluster 6.1483 24.3333 5.1 28 11.7 Jan M45 0000 Taurus Open Cluster 3.7833 24.1166 0 0 11.7 Jan M1 1952 Taurus Nebula 5.575 22.0166 8.4 6 11.7 Jan M77 1068 Cetus Galaxy 2.7116 -0.0166 8.8 6.9 11.7 Jan M40 0000 Ursa Major Open Cluster 12.3733 58.0833 0 0 10.2 Feb M108 3556 Ursa Major Galaxy 11.1916 55.6666 10.1 8.3 10.2 Feb M97 3587 Ursa Major Nebula 11.2466 55.0166 11.2 3.2 10.2 Feb M109 3992 Ursa Major Galaxy 11.96 53.3833 9.8 7.6 10.2 Feb M106 4258 Canes Venatici Galaxy 12.3166 47.3 8.3 18.2 10.2 Feb M44 2632 Cancer Open Cluster 8.6683 19.9833 3.1 95 10.2 Feb M67 2682 Cancer Open Cluster 8.84 11.8166 6.9 30 10.2 Feb M78 2068 Orion Nebula 5.7783 0.05 8 8 10.2 Feb M43 1982 Orion Nebula 5.5933 -5.2666 9 20 10.2 Feb M42 1976 Orion Nebula 5.59 -5.45 4 66 10.2 Feb M101 5457 Ursa Major Galaxy 14.0533 54.35 7.7 26.9 8.3 Mar M102 5457 Ursa Major Galaxy 14.0533 54.35 7.7 26.9 8.3 Mar M51 5194 Canes Venatici Galaxy 13.4983 47.2 8.4 11 8.3 Mar M63 5055 Canes Venatici Galaxy 13.2633 42.0333 8.6 12.3 8.3 Mar M94 4736 Canes Venatici Galaxy 12.8483 41.1166 8.2 11 8.3 Mar M65 3623 Leo Galaxy 11.315 13.0833 9.3 10 8.3 Mar M66 3627 Leo Galaxy 11.3366 12.9833 9 8.7 8.3 Mar M105 3379 Leo Galaxy 10.7966 12.5833 9.3 4.5 8.3 Mar M96 3368 Leo Galaxy 10.78 11.8166 9.2 7.1 8.3 Mar M95 3351 Leo Galaxy 10.7333 11.7 9.7 7.4 8.3 Mar M48 2548 Hydra Open Cluster 8.23 -5.8 5.8 54 8.3 Mar M50 2323 Monoceros Open Cluster 7.0533 -8.3333 5.9 16 8.3 Mar M Appendices NGC constellation type DEC RA [hr] [deg] mag size [arcmin] imaging [hr] visible from M3 5272 Canes Venatici Glob Cluster 13.7033 28.3833 6.4 16.2 5.9 Apr M64 4826 Coma Berenices Galaxy 12.945 21.6833 8.5 9.3 5.9 Apr M85 4382 Coma Berenices Galaxy 12.4233 18.1833 9.2 7.1 5.9 Apr M53 5024 Coma Berenices Glob Cluster 13.215 18.1666 7.7 12.6 5.9 Apr M100 4321 Coma Berenices Galaxy 12.3816 15.8166 9.4 6.9 5.9 Apr M98 4192 Coma Berenices Galaxy 12.23 14.9 10.1 9.5 5.9 Apr M91 4548 Coma Berenices Galaxy 12.59 14.5 10.2 5.4 5.9 Apr M99 4254 Coma Berenices Galaxy 12.3133 14.4166 9.8 5.4 5.9 Apr M88 4501 Coma Berenices Galaxy 12.5333 14.4166 9.5 6.9 5.9 Apr M90 4569 Virgo Galaxy 12.6133 13.1666 9.5 9.5 5.9 Apr M86 4406 Virgo Galaxy 12.4366 12.95 9.2 7.4 5.9 Apr M84 4374 Virgo Galaxy 12.4183 12.8833 9.3 5 5.9 Apr M89 4552 Virgo Galaxy 12.595 12.55 9.8 4.2 5.9 Apr M87 4486 Virgo Galaxy 12.5133 12.4 8.6 7.2 5.9 Apr M58 4579 Virgo Galaxy 12.6283 11.8166 9.8 5.4 5.9 Apr M59 4621 Virgo Galaxy 12.7 11.65 9.8 5.1 5.9 Apr M60 4649 Virgo Galaxy 12.7283 11.55 8.8 7.2 5.9 Apr M49 4472 Virgo Galaxy 12.4966 8 8.4 8.9 5.9 Apr M61 4303 Virgo Galaxy 12.365 4.4666 9.7 6 5.9 Apr M92 6341 Hercules Glob Cluster 17.285 43.1333 6.5 11.2 2.3 May M13 6205 Hercules Glob Cluster 16.695 36.4666 5.9 16.6 2.3 May M5 5904 Serpens Glob Cluster 15.31 2.0833 5.8 17.4 2.3 May M52 7654 Cassiopeia Open Cluster 23.4033 61.5833 6.9 13 0 Jun M103 581 Open Cluster 1.5533 60.7 7.4 6 0 Jun M39 7092 Cygnus Open Cluster 21.5366 48.4333 4.6 32 0 Jun M29 6913 Cygnus Open Cluster 20.3983 38.5333 6.6 7 0 Jun M57 6720 Lyra Nebula 18.8933 33.0333 9 2.5 0 Jun M56 6779 Lyra Glob Cluster 19.2766 30.1833 8.3 7.1 0 Jun M27 6853 Vulpecula Nebula 19.9933 22.7166 8.1 15.2 0 Jun M71 6838 Sagitta Glob Cluster 19.89667 18.78333 8.3 7.2 0 Jun M14 6402 Ophiuchus Glob Cluster 17.62667 -3.25 7.6 11.7 0 Jun M11 6705 Scutum Open Cluster 18.85167 -6.26667 5.8 14 0 Jun M15 7078 Pegasus Glob Cluster 21.5 6.4 12.3 0.5 Jul M12 6218 Ophiuchus Glob Cluster 16.78667 -1.95 6.6 14.5 0.5 Jul M10 6254 Ophiuchus Glob Cluster 16.95167 -4.1 6.6 15.1 0.5 Jul M26 6694 Scutum Open Cluster 18.75333 -9.4 8 15 0.5 Jul M76 650 Nebula 1.705 12 4.8 4.6 Aug Cassiopeia Perseus 12.16667 51.56667 271 272 The Astrophotography Manual M NGC constellation RA type [hr] DEC [deg] mag size [arcmin] imaging [hr] visible from M110 205 Andromeda Galaxy 0.67333 41.68333 8 17.4 4.6 Aug M31 224 Andromeda Galaxy 0.71167 41.26667 3.5 178 4.6 Aug M32 221 Andromeda Galaxy 0.71167 40.86667 8.2 7.6 4.6 Aug M2 7089 Aquarius Glob Cluster 21.55833 -0.81667 6.5 12.9 7.5 Sep M34 1039 Perseus Open Cluster 2.7 42.78333 5.2 35 7.5 Sep M33 598 Triangulum Galaxy 1.565 30.65 5.7 62 9.5 Oct M74 628 Pisces Galaxy 1.61167 15.78333 9.2 10.2 11.2 Nov M38 1912 Auriga Open Cluster 5.47833 35.83333 6.4 21 12 Dec M36 1960 Auriga Open Cluster 5.60167 34.13333 6 12 12 Dec M37 2099 Auriga Open Cluster 5.87333 32.55 5.6 24 12 Dec Messier Data – full listing This alternative database lists all the Messier objects and is compiled from various databases on the Internet, including those linked to by SEDS and others. The object size is shown by means of its longest dimension and I noted that published values vary slightly between sources. Messier only worked in the Northern Hemisphere and his list excludes those deep space objects visible only from the Southern Hemisphere. For that, the Caldwell Catalog goes a long way to make amends. RA size [hr min] [deg min] DEC mag Remnant 5 34.5 22 1 8.4 6 Aqr G Cluster 21 33.5 0 49 6.5 12.9 CVn G Cluster 13 42.2 28 23 6.2 16.2 Sco G Cluster 16 23.6 -26 32 5.6 26.3 5904 SerCap G Cluster 15 18.6 25 5.6 17.4 6 6405 Sco O Cluster 17 40.1 -32 13 5.3 15 Butterfly Cluster 7 6475 Sco O Cluster 17 53.9 -34 49 4.1 80 The Scorpion’s Tail, Ptolemy’s Cluster 8 6523 Sgr D Nebula 18 3.8 -24 23 6 90 Lagoon Nebula 9 6333 Oph G Cluster 17 19.2 -18 31 7.7 9.3 10 6254 Oph G Cluster 16 57.1 -4 6 6.6 15.1 12 6218 Oph G Cluster 16 47.2 -1 57 6.7 14.5 13 6205 Her G Cluster 16 41.7 36 28 5.8 16.6 14 6402 Oph G Cluster 17 37.6 -3 15 7.6 11.7 15 7078 Peg G Cluster 21 30 12 10 6.2 12.3 16 6611 SerCau O Cluster 18 18.8 -13 47 6.4 35 associated with the Eagle Nebula 17 6618 Sgr D Nebula 18 20.8 -16 11 7 46 Omega, Swan, Horseshoe, or Lobster Nebula 18 6613 Sgr O Cluster 18 19.9 -17 8 7.5 9 M NGC const. type 1 1952 Tau 2 7089 3 5272 4 6121 5 [arcmin] common name Crab Nebula Hercules Globular Cluster Appendices 273 [hr min] [deg min] DEC mag G Cluster 17 2.6 -26 16 6.8 13.5 Sgr D Nebula 18 2.6 -23 2 9 28 6531 Sgr O Cluster 18 4.6 -22 30 6.5 13 6656 Sgr G Cluster 18 36.4 -23 54 5.1 24 23 6494 Sgr O Cluster 17 56.8 -19 1 6.9 27 24 6603 Sgr Patch 18 16.9 -18 29 4.6 5 25 0 Sgr O Cluster 18 31.6 -19 15 6.5 40 26 6694 Sct O Cluster 18 45.2 -9 24 8 15 27 6853 Vul P Nebula 19 59.6 22 43 7.4 15.2 28 6626 Sgr G Cluster 18 24.5 -24 52 6.8 11.2 29 6913 Cyg O Cluster 20 23.9 38 32 7.1 7 30 7099 Cap G Cluster 21 40.4 -23 11 7.2 11 31 224 And S Galaxy 0 42.7 41 16 3.4 178 32 221 And E Galaxy 0 42.7 40 52 8.1 8 near Andromeda Galaxy 33 598 Tri S Galaxy 1 33.9 30 39 5.7 62 Triangulum Galaxy 34 1039 Per O Cluster 2 42 42 47 5.5 35 35 2168 Gem O Cluster 6 8.9 24 20 5.3 28 36 1960 Aur O Cluster 5 36.1 34 8 6.3 12 37 2099 Aur O Cluster 5 52.4 32 33 6.2 24 38 1912 Aur O Cluster 5 28.4 35 50 7.4 21 39 7092 Cyg O Cluster 21 32.2 48 26 4.6 32 40 0 UMa Binary 12 22.4 58 5 8.4 0.8 41 2287 CMa O Cluster 6 46 -20 44 4.6 38 42 1976 Ori D Nebula 5 35.4 -5 27 4 66 Orion Nebula 43 1982 Ori D Nebula 5 35.6 -5 16 9 20 De Mairan’s Nebula, part of Orion Nebula 44 2632 Cnc O Cluster 8 40.1 19 59 3.7 95 Beehive Cluster 45 0 Tau O Cluster 3 47 24 7 1.6 100 Pleiades 46 2437 Pup O Cluster 7 41.8 -14 49 6 27 47 2422 Pup O Cluster 7 36.6 -14 30 5.2 30 48 2548 Hya O Cluster 8 13.8 -5 48 5.5 54 49 4472 Vir E Galaxy 12 29.8 80 8.4 9 50 2323 Mon O Cluster 7 3.2 -8 20 6.3 16 51 5194 CVn S Galaxy 13 29.9 47 12 8.4 11 52 7654 Cas O Cluster 23 24.2 61 35 7.3 13 53 5024 Com G Cluster 13 12.9 18 10 7.6 12.6 54 6715 Sgr G Cluster 18 55.1 -30 29 7.6 9.1 55 6809 Sgr G Cluster 19 40 -30 58 6.3 19 M NGC const. type 19 6273 Oph 20 6514 21 22 RA size [arcmin] common name Trifid Nebula Sagittarius Star Cloud Dumbbell Nebula Andromeda Galaxy Winnecke 4 Whirlpool Galaxy 274 The Astrophotography Manual [hr min] [deg min] DEC mag G Cluster 19 16.6 30 11 8.3 7.1 P Nebula 18 53.6 33 2 8.8 2.5 Vir S Galaxy 12 37.7 11 49 9.7 5.5 Vir E Galaxy 12 42 11 39 9.6 5.1 4649 Vir E Galaxy 12 43.7 11 33 8.8 7.2 61 4303 Vir S Galaxy 12 21.9 4 28 9.7 6 62 6266 Oph G Cluster 17 1.2 -30 7 6.5 14.1 63 5055 CVn S Galaxy 13 15.8 42 2 8.6 12.3 Sunflower Galaxy 64 4826 Com S Galaxy 12 56.7 21 41 8.5 9.3 Blackeye Galaxy 65 3623 Leo S Galaxy 11 18.9 13 5 9.3 8 in the Leo Triplett 66 3627 Leo S Galaxy 11 20.2 12 59 8.9 8.7 in the Leo Triplett 67 2682 Cnc O Cluster 8 50.4 11 49 6.1 30 68 4590 Hya G Cluster 12 39.5 -26 45 7.8 12 69 6637 Sgr G Cluster 18 31.4 -32 21 7.6 7.1 70 6681 Sgr G Cluster 18 43.2 -32 18 7.9 7.8 71 6838 Sge G Cluster 19 53.8 18 47 8.2 7.2 73 6994 Aqr Asterism 20 58.9 -12 38 9 2.8 74 628 Psc S Galaxy 1 36.7 15 47 9.4 1 0.2 75 6864 Sgr G Cluster 20 6.1 -21 55 8.5 6 76 650 Per P Nebula 1 42.4 51 34 0.1 4.8 77 1068 Cet S Galaxy 2 42.7 01 8.9 7 78 2068 Ori D Nebula 5 46.7 03 8.3 8 79 1904 Lep G Cluster 5 24.5 -24 33 7.7 8.7 80 6093 Sco G Cluster 16 17 -22 59 7.3 8.9 81 3031 UMa S Galaxy 9 55.6 69 4 6.9 25.7 Bode’s Galaxy 82 3034 UMa I Galaxy 9 55.8 69 41 8.4 11.2 Cigar Galaxy 83 5236 Hya S Galaxy 13 37 -29 52 7.6 11.2 Southern Pinwheel 84 4374 Vir L Galaxy 12 25.1 12 53 9.1 5 85 4382 Com L Galaxy 12 25.4 18 11 9.1 7.1 86 4406 Vir L Galaxy 12 26.2 12 57 8.9 7.4 87 4486 Vir E Galaxy 12 30.8 12 24 8.6 7.2 88 4501 Com S Galaxy 12 32 14 25 9.6 6.9 89 4552 Vir E Galaxy 12 35.7 12 33 9.8 4.2 90 4569 Vir S Galaxy 12 36.8 13 10 9.5 9.5 91 4548 Com S Galaxy 12 35.4 14 30 0.2 5.4 92 6341 Her G Cluster 17 17.1 43 8 6.4 11.2 93 2447 Pup O Cluster 7 44.6 -23 52 6 22 94 4736 CVn S Galaxy 12 50.9 41 7 8.2 11 M NGC const. type 56 6779 Lyr 57 6720 Lyr 58 4579 59 4621 60 RA size [arcmin] common name Ring Nebula Little Dumbbell Nebula Cetus A Virgo A Appendices [hr min] [deg min] DEC mag S Galaxy 10 44 11 42 9.7 7.4 Leo S Galaxy 10 46.8 11 49 9.2 7.1 3587 UMa P Nebula 11 14.8 55 1 9.9 3.2 4192 Com S Galaxy 12 13.8 14 54 0.1 9.5 99 4254 Com S Galaxy 12 18.8 14 25 9.9 5.4 100 4321 Com S Galaxy 12 22.9 15 49 9.3 6.9 101 5457 UMa S Galaxy 14 3.2 54 21 7.9 26.9 Pinwheel Galaxy 102 5457 UMa S Galaxy 14 3.2 54 21 7.9 26.9 duplicates M101 103 581 Cas O Cluster 1 33.2 60 42 7.4 6 104 4594 Vir S Galaxy 12 40 -11 37 8 8.3 105 3379 Leo E Galaxy 10 47.8 12 35 9.3 4.5 106 4258 CVn S Galaxy 12 19 47 18 8.4 18.2 107 6171 Oph G Cluster 16 32.5 -13 3 7.9 10 108 3556 UMa S Galaxy 11 11.5 55 40 0 8.3 109 3992 UMa S Galaxy 11 57.6 53 23 9.8 7.6 110 205 And E Galaxy 0 40.4 41 41 8.5 17.4 M NGC const. type 95 3351 Leo 96 3368 97 98 RA size 275 common name [arcmin] Owl Nebula Sombrero Galaxy a satellite of the Andromeda Galaxy Caldwell Catalog The Caldwell Catalog, by the late Sir Patrick Moore, documents a number of notable omissions from the Messier list and includes significant objects for observers in the southern hemisphere. The Caldwell Catalog is listed in order of distance from the North Celestial Pole. The most southern objects are given the highest catalog numbers. It is not the last word in deep space objects but is a good starting point after the Messier list. Several of the first light assignments are of Caldwell objects. Caldwell NGC const. type RA DEC mag. size 1 188 Cep Open Cluster 00 44.4 +85 20 8.1 14 2 40 Cep Planetary Nebula 00 13.0 +72 32 11.6 0.6 3 4236 Dra Spiral Barred Galaxy 12 16.7 +69 28 9.7 21 4 7023 Cep Bright Nebula 21 01.8 +68 12 6.8 18 5 IC 342 Cam Spiral Galaxy 03 46.8 +68 06 9.2 18 6 6543 Dra Planetary Nebula 17 58.6 +66 38 8.8 5.8 7 2403 Cam Spiral Galaxy 07 36.9 +65 36 8.9 18 8 559 Cas Open Cluster 01 29.5 +63 18 9.5 4 9 Sh2-155 Cep Bright Nebula 22 56.8 +62 37 7.7 50 10 663 Cas Open Cluster 01 46.0 +61 15 7.1 16 common name Bow Tie Nebula Iris Nebula Cat’s Eye Nebula Cave Nebula 276 The Astrophotography Manual Caldwell NGC const. type RA DEC mag. size 11 12 7635 Cas Bright Nebula 23 20.7 6946 Cep Spiral Galaxy 20 34.8 13 457 Cas Open Cluster 14 869/884 Per 15 6826 Cyg 16 7243 17 147 18 185 19 common name +61 12 7 15 +60 09 9.7 11 01 19.1 +58 20 6.4 13 Owl or E.T. Cluster Open Cluster 02 20.0 +57 08 4.3 30 Double Cluster, h & chi Persei Planetary Nebula 19 44.8 +50 31 9.8 2.3 Blinking Planetary Lac Open Cluster 22 15.3 +49 53 6.4 21 Cas Elliptical Galaxy 00 33.2 +48 30 9.3 13 Cas Elliptical Galaxy 00 39.0 +48 20 9.2 12 IC 5146 Cyg Bright Nebula 21 53.5 +47 16 10 12 Cocoon Nebula 20 7000 Cyg Bright Nebula 20 58.8 +44 20 6 120 North America Nebula 21 4449 CVn Irregular Galaxy 12 28.2 +44 06 9.4 5 22 7662 And Planetary Nebula 23 25.9 +42 33 9.2 2.2 23 891 And Spiral Barred Galaxy 02 22.6 +42 21 9.9 14 24 1275 Per Seyfert Galaxy 03 19.8 +41 31 11.6 2.6 25 2419 Lyn Globular Cluster 07 38.1 +38 53 10.4 4.1 26 4244 CVn Spiral Galaxy 12 17.5 +37 49 10.6 16 27 6888 Cyg Bright Nebula 20 12.0 +38 21 7.5 20 28 752 And Open Cluster 01 57.8 +37 41 5.7 50 29 5005 CVn Spiral Barred Galaxy 13 10.9 +37 03 9.8 5.4 30 7331 Peg Spiral Barred Galaxy 22 37.1 +34 25 9.5 11 31 IC 405 Aur Bright Nebula 05 16.2 +34 16 6 19 32 4631 CVn Spiral Galaxy 12 42.1 +32 32 9.3 15 Whale Galaxy 33 6992/5 Cyg Supernova Remnant 20 56.4 +31 43 - 60 East Veil Nebula 34 6960 Cyg Supernova Remnant 20 45.7 +30 43 - 70 West Veil Nebula 35 4889 Com Elliptical Galaxy 13 00.1 +27 59 11.4 3 36 4559 Com Spiral Galaxy 12 36.0 +27 58 9.8 10 37 6885 Vul Open Cluster 20 12.0 +26 29 5.7 7 38 4565 Com Spiral Barred Galaxy 12 36.3 +25 59 9.6 16 Needle Galaxy 39 2392 Gem Planetary Nebula 07 29.2 +20 55 9.9 0.7 Eskimo or Clown Nebula 40 3626 Leo Spiral Barred Galaxy 11 20.1 +18 21 10.9 3 Bubble nebula Blue Snowball Perseus A Crescent Nebula Flaming Star Nebula Caldwell Appendices NGC const. type RA DEC mag. size 41 - 42 7006 Tau Open Cluster 04 27.0 Del Globular Cluster 21 01.5 +16 00 1 330 +16 11 10.6 2.8 43 7814 Peg Spiral Barred Galaxy 00 03.3 +16 09 10.5 6 44 7479 Peg Spiral Barred Galaxy 23 04.9 +12 19 11 4 45 5248 Boo Spiral Galaxy 13 37.5 +08 53 10.2 6 46 2261 Mon Bright Nebula 06 39.2 +08 44 10 2 47 6934 Del Globular Cluster 20 34.2 +07 24 8.9 6 48 2775 Can Spiral Galaxy 09 10.3 +07 02 10.3 4.5 49 2237-9 Mon Bright Nebula 06 32.3 +05 03 - 80 50 2244 Mon Open Cluster 06 32.4 +04 52 4.8 24 common name Hyades Hubble’s Variable Nebula Rosette Nebula 51 IC 1613 Cet Irregular Galaxy 01 04.8 +02 07 9 12 52 4697 Vir Elliptical Galaxy 12 48.6 -05 48 9.3 6 53 3115 Sex Elliptical Galaxy 10 05.2 -07 43 9.1 8 54 2506 Mon Open Cluster 08 00.2 -10 47 7.6 7 55 7009 Aqr Planetary Nebula 21 04.2 -11 22 8.3 2.5 56 246 Cet Planetary Nebula 00 47.0 -11 53 8 3.8 57 6822 Sgr Irregular Galaxy 19 44.9 -14 48 9.3 10 58 2360 CMa Open Cluster 07 17.8 -15 37 7.2 13 59 3242 Hya Planetary Nebula 10 24.8 -18 38 8.6 0.25 Ghost of Jupiter 60 4038 Crv Spiral Galaxy 12 01.9 -18 52 11.3 2.6 Antennae Galaxies 61 4039 Crv Spiral Galaxy 12 01.9 -18 53 13 3.2 Antennae Galaxies 62 247 Cet Spiral Galaxy 00 47.1 -20 46 8.9 20 63 7293 Aqr Planetary Nebula 22 29.6 -20 48 6.5 13 64 2362 CMa Open Cluster 07 18.8 -24 57 4.1 8 65 253 Scl Spiral Galaxy 00 47.6 -25 17 7.1 25 66 5694 Hya Globular Cluster 14 39.6 -26 32 10.2 3.6 67 1097 For Spiral Barred Galaxy 02 46.3 -30 17 9.2 9 68 6729 CrA Bright Nebula 19 01.9 -36 57 9.7 1 69 6302 Sco Planetary Nebula 17 13.7 -37 06 12.8 0.8 70 300 Scl Spiral Galaxy 00 54.9 -37 41 8.1 20 71 2477 Pup Open Cluster 07 52.3 -38 33 5.8 27 72 55 Scl Spiral Barred Galaxy 00 14.9 -39 11 8.2 32 73 1851 Col Globular Cluster 05 14.1 -40 03 7.3 11 Spindle Galaxy Saturn Nebula Barnard’s Galaxy Helix Nebula Sculptor Galaxy Bug Nebula 277 278 The Astrophotography Manual Caldwell NGC const. type RA DEC mag. size common name 74 75 3132 Vel Planetary Nebula 10 07.7 -40 26 8.2 0.8 Eight Burst Nebula 6124 Sco Open Cluster 16 25.6 -40 40 5.8 29 76 6231 Sco Open Cluster 16 54.0 -41 48 2.6 15 77 5128 Cen Peculiar Galaxy 13 25.5 -43 01 7 18 78 6541 CrA Globular Cluster 18 08.0 -43 42 6.6 13 79 3201 Vel Globular Cluster 10 17.6 -46 25 6.7 18 80 5139 Cen Globular Cluster 13 26.8 -47 29 3.6 36 81 6352 Ara Globular Cluster 17 25.5 -48 25 8.1 7 82 6193 Ara Open Cluster 16 41.3 -48 46 5.2 15 83 4945 Cen Spiral Galaxy 13 05.4 -49 28 9.5 20 84 5286 Cen Globular Cluster 13 46.4 -51 22 7.6 9 85 IC 2391 Vel Open Cluster 08 40.2 -53 04 2.5 50 86 6397 Ara Globular Cluster 17 40.7 -53 40 5.6 26 87 1261 Hor Globular Cluster 03 12.3 -55 13 8.4 7 88 5823 Cir Open Cluster 15 05.7 -55 36 7.9 10 89 6087 Nor Open Cluster 16 18.9 -57 54 5.4 12 90 2867 Car Planetary Nebula 09 21.4 -58 19 9.7 0.2 91 3532 Car Open Cluster 11 06.4 -58 40 3 55 92 3372 Car Bright Nebula 10 43.8 -59 52 6.2 120 93 6752 Pav Globular Cluster 19 10.9 -59 59 5.4 20 94 4755 Cru Open Cluster 12 53.6 -60 20 4.2 10 95 6025 TrA Open Cluster 16 03.7 -60 30 5.1 12 96 2516 Car Open Cluster 07 58.3 -60 52 3.8 30 97 3766 Cen Open Cluster 11 36.1 -61 37 5.3 12 98 4609 Cru Open Cluster 12 42.3 -62 58 6.9 5 99 - Cru Dark Nebula 12 53.0 -63 00 - 400 Coalsack Nebula 100 IC 2944 Cen Open Cluster 11 36.6 -63 02 4.5 15 Lambda Centauri Nebula 101 6744 Pav Spiral Barred Galaxy 19 09.8 -63 51 9 16 102 IC 2602 Car Open Cluster 10 43.2 -64 24 1.9 50 Theta Car Cluster 103 2070 Dor Bright Nebula 05 38.7 -69 06 1 40 Tarantula Nebula 104 362 Tuc Globular Cluster 01 03.2 -70 51 6.6 13 105 4833 Mus Globular Cluster 12 59.6 -70 53 7.3 14 106 104 Tuc Globular Cluster 00 24.1 -72 05 4 31 107 6101 Aps Globular Cluster 16 25.8 -72 12 9.3 11 108 4372 Mus Globular Cluster 12 25.8 -72 40 7.8 19 109 3195 Cha Planetary Nebula 10 09.5 -80 52 11.6 40 Centaurus A Omega Centauri Omicron Vel Cluster S Norma Cluster Eta Carinae Nebula Jewel Box 47 Tucanae Appendices Useful Formulae Most of the relevant formulae are shown throughout the book in their respective chapters. This selection may come in useful too: Autoguider Rate This calculates the autoguider rate, in pixels per second, as required by many capture programs. The guide rate is the fraction of the sidereal rate: autoguider rate = 15.04 • guide rate • cos(declination) autoguider resolution (arcsec/pixel) Multiplying this by the minimum and maximum moves (seconds) in the guider settings provides the range of correction values from an autoguider cycle. Polar Drift Rate This calculates the drift rate in arc seconds for a known polar misalignment: declination drift(arcsecs) = drift time(mins) • cos(declination) • polar error (arcmins) 3.81 Polar Error Conversely, this indicates the polar alignment error from a measured drift rate: polar error (arcmins) = 3.81• declination drift(arcsecs) drift time(mins) • cos(declination) Dust Distance This calculates the optical distance in millimeters, of the offending dust particle, by its shadow diameter on an image. The CCD pitch is in microns: distance = CCD pitch • focal ratio • shadow diameter in pixels Periodic Error This calculates the periodic error in arc seconds for a given declination and pixel drift: periodic error (arc seconds)= pixel drift • CCD resolution (arcsec/pixel) cos(declination) Critical Focus Zone This alternative equation calculates the zone of acceptable focus for a given set of seeing conditions and uses a quality factor Q (a percentage defocus contribution to the overall seeing conditions). (f is the focal ratio.) : critical focus zone (microns) = seeing (arcsecs) • aperture (mm) • f 2 • Q 279