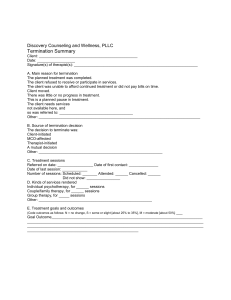

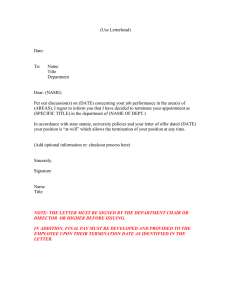

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259553073 How Does Project Termination Impact Project Team Members? Rapid Termination, “Creeping Death,” and Learning From Failure Article in Journal of Management Studies · October 2013 DOI: 10.1111/joms.12068 CITATIONS READS 95 8,112 4 authors, including: Dean A. Shepherd Holger Patzelt University of Notre Dame Technische Universität München 365 PUBLICATIONS 38,265 CITATIONS 163 PUBLICATIONS 10,982 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Trenton A Williams Indiana University Bloomington 41 PUBLICATIONS 2,405 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Entrepreneurial Grief View project Entrepreneurial action View project All content following this page was uploaded by Trenton A Williams on 18 October 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. SEE PROFILE bs_bs_banner Journal of Management Studies 51:4 June 2014 doi: 10.1111/joms.12068 How Does Project Termination Impact Project Team Members? Rapid Termination, ‘Creeping Death’, and Learning from Failure Dean A. Shepherd, Holger Patzelt, Trenton A. Williams and Dennis Warnecke Kelley School of Business, Indiana University; Technische Universität München; Kelley School of Business, Indiana University; Technische Universität München ABSTRACT Although extant studies have increased our understanding of the decision of when to terminate a project and its organizational implications, they do not explore the contextual mechanisms underlying the link between the speed at which a project is terminated and the learning of those directly working on the project. This is surprising because perceptions of project failure likely differ between those who own the option (i.e., the decision maker) and those who are the option (i.e., project team members). In this multiple case study, we explored research and development (R&D) subsidiaries within a large multinational parent organization and generated several new insights: (1) rather than alleviate negative emotions, delayed termination was perceived as creeping death, thwarting new career opportunities and generating negative emotions; (2) rather than obstructing learning from project experience, negative emotions motivated sensemaking efforts; and (3) rather than emphasizing learning after project termination, in the context of rapid redeployment of team members after project termination, delayed termination provided employees the time to reflect on, articulate, and codify lessons learned. We discuss the implications of these findings. Keywords: entrepreneurship, failure, innovation, learning, project, termination INTRODUCTION Central to an organization’s efforts to manage uncertainty is its ability to pursue multiple projects, terminate poorly performing projects quickly, redeploy resources to those projects that show promise, and learn from failure (McGrath, 1999). Failure refers to the termination of an initiative to create value that has fallen short of its goals (Hoang and Rothaermel, 2005; McGrath, 1999; Shepherd et al., 2011; see Ucbasaran et al., 2013 for a review), which can signal the need to revise one’s belief systems and motivates sensemaking efforts Address for reprints: Dean A. Shepherd, Kelley School of Business, Indiana University, 1309 E. Tenth St., Bloomington, IN 47405, USA (shepherd@indiana.edu). © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies 514 D. A. Shepherd et al. (Chuang and Baum, 2003; Pangarkar, 2009). Although there is widespread acknowledgment of the importance of learning from failure, most organizational members find doing so to be quite difficult (Cannon and Edmondson, 2005; Prahalad and Oosterveld, 1999). Indeed, despite the opportunity to learn from failure, organizational members face a number of obstacles to doing so, including individuals’ orientation towards learning (Dweck and Leggett, 1988), cognitive biases (Kahneman et al., 1982), emotional interference (Shepherd et al., 2011) and past successes (Miller, 1994), a competitive orientation between an organization’s teams (Tjosvold et al., 2004), and an organizational context that punishes failure (Cannon and Edmondson, 2001; Prahalad and Oosterveld, 1999). From a cognitive perspective, the timing of a corporate entrepreneur’s decision to terminate a project impacts organizational learning from failure: both terminating early (based on the corporate entrepreneur’s ‘undisciplined’ termination script) and terminating late (based on the corporate entrepreneur’s innovation drift script) obstruct learning from failure (Corbett et al., 2007). Project termination refers to the release of a project’s resources and the reassignment of project team members to other duties (Pinto and Prescott, 1988, 1990) and is a complex ‘dynamic advocacy process that unfolds over time and is influenced by performance judgments and performance thresholds [of the managers involved]’ (Green et al., 2003, p. 419). Investigating termination speed’s impact on both the generation of emotion and learning from failure addresses an important gap in the literature because there is considerable variance in the timing of project termination. While some projects are subject to rapid termination – namely, the decision to end the projects was unequivocal and final, and there was little time from expecting termination to actual termination – others appear to ‘fail’ over an extended period (Green et al., 2003). This delayed project termination – namely, termination was anticipated and drawn out over an extended period of time – has been found to negatively influence stockholder opinion of the project (until it is finally terminated) (Statman and Sepe, 1989) and overall firm value (Clinebell and Clinebell, 1994). Although these studies have increased our understanding of the cognitions underlining the timing of the decision to terminate a project and its learning implications from the perspective of the corporate entrepreneur, we take the perspective of those working on the project (i.e., the project team members). That is, what are the contextual mechanisms that link the speed of project termination to team members’ learning from the experience? This additional perspective is important because there are likely important differences in reactions to project failure between those who ‘own the option’ (i.e., those who make the decision to terminate) and those who ‘are the option’ (i.e., those who work on the project being terminated) (McGrath et al., 2004, p. 96). As prior research has explored real options reasoning from the perspective of top management (those who own the option) but not from the perspective of project team members (those who are the option) and because project team members are likely to react differently to project failure than those with the authority to make the termination decision, we use a multiple case study approach in this article to theorize on the topic. A multiple case study approach provides the opportunity to generate new insights not available through deductive theorizing (Brown and Eisenhardt, 1997). © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies Creeping Death and Learning from Failure 515 The setting is research and development (R&D) subsidiaries within a large multinational parent organization. This is an attractive setting for investigating the link between speed of project termination and learning because R&D projects are exploratory vehicles for large established organizations that lead to highly variable outcomes, including failure (McGrath, 1999). However, R&D projects, termination processes, and outcomes are also typically shrouded in secrecy in this context. Work on these projects represents intellectual property, and secrecy is a common method to protect that property. Due to our personal network, we were granted uncommon access to information on substantial R&D projects, including access to team members, project leaders, the top management of the subsidiary organizations, the top management of the parent organization, and (secret and personal) internal documents. R&D is considered a key component to the parent organization’s overall operations, and the parent has a reputation for generating both groundbreaking and important incremental innovations. Most R&D project team members are engineers and scientists who view advancing knowledge and excellence in finding engineering solutions (i.e., chemical, electrical, mechanical, or computer) as the most significant element of their work. Despite these work values, team members need to balance their fascination with the science of their work with the commercialization of its output, especially when faced with project failure situations. Managers overseeing R&D projects in this company frequently weigh decisions regarding potential and existing project viability and must sometimes terminate projects despite sizable investments from the parent company, customers, and public institutions. On average, in the current setting, a project receives a US$40 million investment, involves 2000 full-time equivalent employee months, and takes one to two years to achieve an outcome (including failed projects). Our study offers three primary contributions to the literature. First, research has established that entrepreneurial endeavours (i.e., projects and businesses) are important to those who pursue them (Shepherd, 2003; Shepherd et al., 2009b; see also Ucbasaran et al., 2013 for a review). The failure of these entrepreneurial endeavours generates negative emotional reactions (Cardon and McGrath, 1999; Cope, 2011; Shepherd, 2003), and negative emotions obstruct learning (Cope, 2011; Singh et al., 2007; Ucbasaran et al., 2010). We extend these streams of research by acknowledging that negative emotions are generated by the loss of something important (Archer, 1999). However, for the project team members in the current study, it was not the project that was highly important (i.e., project failure did not generate negative emotions); rather, they found the engineering challenge of working on solving current problems critical to the organization to be highly important. It was the loss of the opportunity to move on to the next engineering challenge that generated negative emotions. Therefore, to understand the generation of negative emotions from failure, we need to understand what of importance is being lost from the team members’ perspective. Second, rather than the failure event triggering members’ learning from their experiences (Chuang and Baum, 2003; McGrath, 2001; Prencipe and Tell, 2001; Sitkin, 1992), we found that for these R&D engineers, the termination event ended members’ learning from their project experiences. For the engineers in our study, the termination event led to immediate redeployment to other projects with little to no opportunity or motivation to allocate time and energy to reflect on the failed project. Under conditions of rapid © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies 516 D. A. Shepherd et al. redeployment, it appears that the activities necessary to learn from the project experience occur during the period of delayed termination (i.e., reflection, articulation, and codification; Zollo and Winter, 2002). Delayed termination provided a small window of time that enabled (and negative emotions motivated) team members to reflect on, articulate, and codify lessons learned – reflection-in-action. This finding complements studies advocating for after action (post-failure) reviews (Cannon and Edmondson, 2005; Ellis and Davidi, 2005; Prencipe and Tell, 2001) by highlighting that, in the context of rapid redeployment of human resources after project termination, some termination delay facilitates in-situ (pre-failure) learning activities. This finding also suggests that an organization can have two but not all three of the attributes advocated under real options reasoning (Brown and Eisenhardt, 1997; McGrath, 1999; McGrath and Cardon, 1997), that is, two (but not all) of (1) rapid termination of failing projects, (2) rapid redeployment of human resources, and (3) learning from project failures. Finally, from a cognitive perspective of the timing of the termination decision, Corbett et al. (2007) found that delayed termination (‘innovation drift’) was associated with poor learning outcomes, and from an emotion perspective, Shepherd et al. (2009b) proposed that some (but not too much) delay in the termination decision would emotionally prepare the decision maker for the loss such that when termination eventually occurs the negative emotional reaction would not be as great. We complement both these studies by finding that in the organizational context of rapid deployment of personnel following project failure, a period of delay is necessary for project team members to learn from their experience. Rather than acting as emotional preparation, this delay was a source of negative emotions that motivated sensemaking. That is, to gain a deeper understanding of the implications of a project’s termination we need to consider the ‘attractiveness’ and the timing of the replacement project and do so from the perspectives of those whose work is impacted by the decision. In the current article, we offer a counter-weight to the extant research on the detrimental impact of negative emotions on learning: we find that negative emotions generated from not being able to move on to the next engineering challenge, coupled with having time to reflect on the project as the termination decision approached, provided the motivation for sensemaking activities and the time to reflect on, articulate, and codify the lessons learned. In contrast, when negative emotions are absent (or low) because the project is terminated rapidly, team members do not have the motivation or the time to learn from the failure experience. Next, we offer a brief review of the literature on learning from failure and project termination as the theoretical context for our study. We then detail our multiple case study method and results as well as discuss the implications of our findings. THEORETICAL CONTEXT Research on learning from failure and research on the decision of when to terminate failing projects has progressed along relatively independent tracks (for an exception from the cognitive perspective of the decision maker, see Corbett et al., 2007), although both are acknowledged as critical to understanding how innovative organizations successfully manage uncertainty (McGrath, 1999; Meyer and Zucker, 1989; van Witteloostuijn, © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies Creeping Death and Learning from Failure 517 1998). In the sub-sections that follow, we briefly review each literature to provide a conceptual context for our study. Learning from Failure Before we set out on our study, we already knew from the management and entrepreneurship literature that learning from failure is an important task (McGrath, 1999; Shepherd and Cardon, 2009; Sitkin, 1992). Failure signals a problem with one’s current beliefs (Chuang and Baum, 2003; Sitkin, 1992) and motivates a search for solutions (Ginsberg, 1988; McGrath, 2001; Morrison, 2002; Petroski, 1985). Indeed, because failure events motivate and inform the acquisition of new knowledge and/or skills, it is believed that individuals can learn more from their failures than their successes (Petroski, 1985; Popper, 1959). According to Sitkin (1992, p. 243), this learning from failure is most likely to take place if the projects ‘(1) result from thoughtfully planned actions, (2) have uncertain outcomes, (3) are of modest scale, (4) are executed and responded to with alacrity, and (5) take place in domains that are familiar enough to permit effective learning.’ However, despite acknowledging the importance of learning from failure, most organizations and organizational members find it difficult to do so (Cannon and Edmondson, 2005). That is, despite the importance of the information revealed by a failure, individuals may not effectively process that information (Weick, 1990; Weick and Sutcliffe, 2007). Although we are gaining a deeper understanding of organizational obstacles to learning from failure (e.g., reward systems that punish (Sitkin, 1992) or even stigmatize (Cannon and Edmondson, 2005) failure), there has been considerable research on obstacles to learning from failure at the individual level. Prominent in this stream of research is attribution theory, which highlights individuals’ tendency to attribute success to themselves (i.e., internal, personal) and attribute failure to others (i.e., external, environmental) (Wagner and Gooding, 1997). By attributing failure to external causes, individuals are able to ‘protect’ their self-esteem, but these attributions obstruct learning because the event is considered to be beyond their realm of influence (Reich, 1949). However, it appears that over time (i.e., since the failure), attributions can become more internal (Frank and Gilovich, 1989), and taking more responsibility for failure (Pronin and Ross, 2006) can remove a considerable obstacle to learning from failure. Over and above the cognitive strategy of attributions representing an obstacle to learning, there are often emotional obstacles to learning from failure. To the extent that a project was important to an individual, its failure can create a negative emotional reaction – grief (Shepherd and Cardon, 2009; Shepherd et al., 2009a, 2011). Although these negative emotions can stimulate the search for information about the project’s failure necessary for learning (Cyert and March, 1963; Kiesler and Sproull, 1982), they interfere with the attention allocation and information processing necessary for an entrepreneur to learn from his or her failure experiences (consistent with Bower, 1992; Fredrickson, 2001). Indeed, previous research has explored the consequences negative emotions have on R&D effectiveness. First, negative emotions ‘narrow individuals’ momentary thought-action repertoire by calling forth specific action tendencies (e.g., attack, flee) . . . [whereas] many positive emotions broaden individuals’ momentary © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies 518 D. A. Shepherd et al. thought-action repertoires, prompting them to pursue a wider range of thoughts and actions than is typical’ (Fredrickson and Branigan, 2005, p. 314). Therefore, R&D groups seeking to generate novel innovations that lead to future products should seek to limit the presence of negative emotions (Fredrickson, 1998). Second, negative emotions have been found to adversely impact organizational members’ affective commitment, which in turn influences members’ willingness to invest personal resources to achieving organizational goals (Allen and Meyer, 1990; O’Reilly and Chatman, 1986; Shepherd et al., 2011). Affective commitment to an organization can enhance organizational performance (Gong et al., 2009) but is a principle that must be balanced with learning from failure, which can also enhance organizational performance (McGrath, 1999). Finally, and consistent with the previous points, negative emotions have been found to ‘narrow people’s attention, making them miss the forest for the trees’ (Fredrickson, 2001, p. 222), interfere with creative or integrative thinking (Estrada et al., 1997; Fredrickson and Branigan, 2005; Isen et al., 1987), and ultimately interfere with learning (Fredrickson and Branigan, 2005; Masters et al., 1979). Over time (i.e., since project failure), these negative emotions appear to subside (Shepherd et al., 2011), removing obstacles to learning from failure. The key insight from the ‘learning from failure’ literature is that learning from failure is an important yet difficult task. Failure triggers cognitive strategies and emotional reactions that obstruct individuals from learning from their experiences. We suspected that grounding our theorizing in data on contextual factors that actually influence project team members’ learning from failure would enable us to generate additional insights. Speed of Project Termination Research on innovation management using a portfolio approach has found that developing an optimal project portfolio not only includes selecting the best projects to start but, equally important, also includes selecting which existing projects to terminate (Brown and Eisenhardt, 1997; Green et al., 2003; McGrath, 1999; Pinto and Prescott, 1990). During the project termination process, a key challenge for organizations is the need to ‘bound’ failure. Existing literature, particularly from economics, has asserted that the costs of failure are bounded by rapidly terminating poorly performing projects (i.e., rapid cessation of project activities) and rapidly redeploying resources to other projects showing promise (i.e., reallocating resources, including people, to new projects or existing projects that show promise) (Ansic and Pugh, 1999; Ohlson, 1980). However, the task of rapid termination is often difficult to accomplish because of the severity of the consequences of termination (Staw and Ross, 1987), the increased personal responsibility associated with the initiative (Staw et al., 1997), and the political or institutional influences that ‘force’ the project to continue (Guler, 2007). Delayed termination has been attributed to a hope for future payout despite current low performance (including the concept of sunk costs) (Arkes and Blumer, 1985; Dixit and Pindyck, 2008), escalation of commitment (Brockner, 1992; Garland et al., 1990), and procrastination (Anderson, 2003; Van Eerde, 2000). For example, a study on the Long Island Lighting Company’s development of the Shoreham Nuclear Power Plant illustrated how the company’s management delayed the termination of the ‘failing’ project so long (more than 23 years) © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies Creeping Death and Learning from Failure 519 that the costs rose from an initial estimate of $75 million to more than $5 billion (when the project was abandoned) (Ross and Staw, 1993). The reasons for this delay included reinforcement traps based on managers’ history of success, errors in information processing, managers’ external justification needs towards policy makers, and political support and institutionalization of the project within the organization (Ross and Staw, 1993). To assist in counteracting potentially costly delays in project termination, some organizations have introduced measures that are supposed to achieve rapid terminations more easily. For example, ongoing project performance monitoring based on milestones and ad hoc reviews consistently evaluates projects’ commercial and technical progress (Pinto and Prescott, 1988). These stage-gate idea-to-launch processes use various data sources to determine project performance and judge whether a project, at its current stage, falls below a critical performance threshold and should be terminated (Cooper, 2008). However, despite these assistance tools and measures, project termination decisions are made by managers who are subject to psychological, social, and contextual influences that make them prone to delay termination more than objective performance data would suggest they should (Green et al., 2003; Schmidt and Calantone, 1998). To summarize, the project termination literature shows that there is considerable variance in how rapidly failing projects are terminated and what are the determinants of delayed termination. What this literature has not yet explored is the link between the speed of the termination and the individuals involved, specifically in terms of their learning from failure. Indeed, the data led to new insights that extended our knowledge of the link between the speed of termination of and learning from the experience. RESEARCH METHOD Design To generate new insights on the contextual factors that link the speed of project termination to team members’ learning from project failures, we use a multiple case study approach as there is relatively little theoretical precedent for deductive study of this topic (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 2008). Using multiple cases allows for cross-case comparisons to recognize and test emerging patterns of relationships among constructs that lead to important theoretical insights (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007; Yin, 2008). Moreover, case studies are particularly appropriate for investigating contextual questions like the one guiding the research in this study (Yin, 2008). Our research setting is an R&Dintensive multinational corporation. The corporation operates in the energy technology industry, manufacturing a wide range of cutting-edge products. It has sales of more than US$20 billion and more than 50,000 employees, and it spends approximately US$1 billion on R&D. With a broad portfolio of research activities and development projects ranging from basic research to customer-initiated developments, not all projects achieve their targeted results (consistent with other R&D organizations); hence, several projects have been terminated, offering an ideal base for our research. We identified relevant cases for this study by having discussions with the chief technology officer (CTO) of the parent corporation, the technology and innovation managers © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies 520 D. A. Shepherd et al. of the parent corporation, and managers of the strategy department of the parent corporation. These discussions revealed four subsidiary organizations that they believed were excellent candidates for the study – these subsidiaries were actively engaged in R&D and had experienced project failures. Specifically, the subsidiary organizations were focused on (1) high-efficiency conventional electricity-generation products, (2) high-efficiency conventional electricity systems, (3) fast-growing decentralized electricity-generation products, and (4) leading technologies for electricity distribution. (Our descriptions of the subsidiaries are deliberately broad so as not to disclose the exact subsidiary organization.) In the next step, we had discussions with the leaders and other members of projects that had been terminated within the four subsidiary organizations. These discussions led to the identification of eight failed projects, two of them nested within each subsidiary. The CTO, subsidiary leads, and project team leaders of these failed projects then assisted in identifying the project team members to interview based on those individuals’ role as the ‘core team’ on the project and their extensive knowledge of the project (management, financials, etc.), the product(s) involved, and other team members. Prior to conducting interviews we held ‘pre-interview’ conversations with each participant to affirm their credibility as data resource. We conducted interviews with team members and project leaders from these failed projects as well as the head of each subsidiary to assess learning from project failure within each subsidiary (see below). Each of these eight projects serves as a unique case for the multiple case study approach, and data regarding these cases were compared and contrasted to identify underlying constructs and explore similarities and differences relevant to learning from failure. Although there were projects nested within subsidiary organizations, there were differences in projects that could not be simply attributed to subsidiary management practices or termination processes. In Table I, we provide details about the selected subsidiaries and their projects as well as about the parent corporation. Figure 1a describes how we conducted interviews at multiple organizational levels. Data Collection Data for each case were collected through interviews, observations, and archival sources. Consistent with many studies using the case study approach (e.g., Gilbert, 2006), our primary source of data was semi-structured interviews. We assigned a hypothetical name to each case (i.e., project) to preserve the anonymity of the organization and its R&D activities. For each failed project, we interviewed four types of respondents at three levels to provide a comprehensive and consistent picture of the subsidiaries across organizational hierarchies. The first two types were team members of the failed project – employees (i.e., lower-level team members) and the project leader. The next level included a member of the top management of the subsidiary organization, and at the highest level, we interviewed a top manager of the parent organization. Therefore, each case consisted of two employee project members, the project leader, a top manager of the subsidiary organization, and a top manager of the parent firm (the one exception is project Bravo, which had one – rather than two – employee team members). We interviewed informants at multiple levels as this leads to more reliable emergent theory as well as richer data for © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies Project type: Product enhancement Time to terminate: ∼4–5 months Budget: ∼US$10 million Employees/man months: ∼15/∼500 Project type: Flagship replacement Time to terminate: Rapid (∼1–2 days) Reason for termination: Failure to achieve efficiency targets Reason for termination: Cost overrun General: Highly efficient conventional electricity systems Sales: >US$3 billion Employees: >5,000 Project Charlie General: Material redesign in new product to replace, reduce cost of existing product Budget: ∼US$1.25 million Employees/man months: ∼6/∼100 Project Cobalt General: Product redesign to improve the efficiency and product life of an existing product. Subsidiary C General: Centralized conventional electricity-generation products and systems Sales: >US$10 billion Employees: >10,000 Project Alpha General: Development of new product generation to Reason for termination: External environment enter new performance level Budget: ∼US$30 million Project type: Flagship project Employees/man months: ∼70/∼1,500 Time to terminate: ∼8 months Project Argon General: Major upgrade of existing product generation, Reason for termination: Cost overrun and external corresponding to new development of major environment components Budget: ∼US$140 million Project type: Flagship replacement Employees/man months: ∼200/∼4,000 Time to terminate: ∼6–8 months Subsidiary A General: A large multinational player in the energy technology industry Sales: >US$20 billion Employees: >50,000 R&D investment: ∼US$1.0 billion Parent organization Subsidiary D Project type: Flagship, new market entry Time to terminate: Rapid (∼1–7 days) Reason for termination: External environment Reason for termination: Cost overruns (due to foreign supplier) Project type: New product innovation Time to terminate: Rapid (∼1 day) General: Leading technologies for electricity distribution Sales: >US$2 billion Employees: >5,000 Project Delta General: Development of new quality measurement Reason for termination: Cost overrun/failure to define product scope of project Budget: ∼US$3 million Project type: New product innovation Employees/man months: ∼15/∼150 Time to terminate: Rapid (∼1–7 days) Project Dubnium General: Developing and integrating a new, Reason for termination: Cost overrun replacement IT system for a foreign-located customer Budget: ∼US$40 million Project type: Flagship project Employees/man months: ∼150/∼4,500 Time to terminate: ∼6 months Budget: ∼US$16 million Employees/man months: ∼50/∼5,000 General: Decentralized, alternative energy products Sales: >US$3 billion Employees: >3,500 Project Bravo General: Material innovation: introduction of new raw material for serial production Budget: ∼US$0.75 million Employees/man months: ∼3/∼9 Project Boron General: Development of new manufacturing location, ramp up of local production Subsidiary B Table I. Details about the projects, subsidiary companies, and parent organization (while maintaining confidentiality) Creeping Death and Learning from Failure 521 © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies 522 D. A. Shepherd et al. a) Interview structure: Multi-level interviews (28 in total) Corporate CTO Subsidiary B Lead Subsidiary A Lead Subsidiary C Lead Subsidiary D Lead Alpha lead Argon lead Bravo lead Boron lead Charlie lead Cobalt lead Delta lead Dubnium lead Team member 1 Team member 1 Team member 1 Team member 1 Team member 1 Team member 1 Team member 1 Team member 1 Team member 2 Team member 2 Team member 2 Team member 2 Team member 2 Team member 2 Team member 2 b) Project periods and data sources Project phase Termination phase • Interviews (INT) • Corporate CTO, Subsidiary management, Project manager and team members • Field notes (FN) • Participant questionnaires (PQ) • Pre-calls with interviewees (PC) • Follow-up discussions (FD) • Internal documents (ID): • Strategy documents (SD) • Performance data (PD) • Employee magazine (EM) • Internal emails / memos (IE) • Company reports / press releases (CR) • Newspaper articles (NA) Post-project phase • Interviews (INT) • Corporate CTO, Subsidiary management, Project manager and team members • Field notes (FN) • Internal emails / memos (IE) • Interviews (INT) • Corporate CTO, Subsidiary management, Project manager and team members • Field notes (FN) • (Technical) lessons learned (LL) • Follow-up discussions (FD) • Company reports / press releases (CR) • Newspaper articles (NA) c) Project timelines and data generation Interview Period Alpha Argon Bravo Boron Charlie Cobalt Delta Dubnium Start: 2003 2007 2006 2008 2011 2010 2009 2012 Real-time data Retrospective data ID: SD PD CR ID: ID: SD EM PD CR ID: SD PD CR IE LL IE NA ID: SD PD CR NA ID: SD PD CR PC INT PQ FD FN Signs of imminent project termination Figure 1. Data collection case comparison (Eisenhardt, 1989; Miller et al., 1997). At the employee and project leader level, all informants were engineers, and consistent with Brown and Eisenhardt (1997), top managers (of subsidiaries) included a mixture of vice presidents of technology and marketing. We conducted two phases of interviews, progressively narrowing the focus of the interviews to the topics that eventually led to the emerging theory in this paper. Initial © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies Creeping Death and Learning from Failure 523 interviews with executives were more exploratory in nature, and we asked about organizational background, the R&D process, team structures, and potential candidates for study. From these semi-structured interviews, we developed initial themes to guide later interview discussions. The second round of interviews entailed 28 in-depth interviews over a four-month period at the respective office locations. Exceptions include a phone interview with one subsidiary manager (he could not be at the interview location due to an unexpected business event) and a phone interview with one project employee who had been reassigned to a different continent. We taped and then transcribed all interviews. We conducted five interviews in the native language of the interviewees, and the rest were conducted in English. Those in the native language were transcribed in that language and then translated into English, and the translations were verified by the second author, who is fluent in English and the native language of the interviewees. Interviews typically lasted about 90 minutes, but some were as long as two hours. The transcribed interviews resulted in 853 single-spaced pages of source material. The project team members’ interviews were structured into five sections: (1) the nature of the project (e.g., the technology, the target market, the size and composition of the team, and the resources invested into the project); (2) the termination event (e.g., how it was terminated, by whom, whether it was anticipated, and if they agreed with the decision); (3) the emotional reaction (if any) to the termination; (4) organizational processes related to project terminations (e.g., processes or routines for regulating emotions or for generating/capturing feedback about failed projects); and (5) learning from the experience and redeployment (e.g., had they learned from the experience, how and when were they redeployed). We used a similar structure (but slightly different questions) for the top managers of both the subsidiary and parent organizations. In addition to conducting interviews, while onsite, we took notes on our impressions and other observations as we engaged in factory tours, product demonstrations, coffee breaks, lunches, and other informal discussions around the interviews. We immediately captured detailed notes while onsite after each interaction (e.g., factory tour, interview, ad hoc conversation, etc.) and held discussions as a group to discuss insights and impressions. These observations, insights, and impressions were captured as ‘field notes’ that we later used to supplement interview transcriptions as well as confirm emerging theoretical perspectives during analysis. Further, we supplemented data from interviews and on-site field observations (conducted post-project termination) with archival records (including meeting agendas and internal emails providing real-time reports before, at, and after project termination) and additional interviews with employees from the central technology office and strategy department (after the project termination). A large part of this information was confidential and only available within the organization – for example, project-level and subsidiary-level performance data, including internal strategy and reporting documents, internal memos/emails, and employee magazines. Some of the internal documents had such high levels of secrecy that they carried ‘internal shadow numbers’, which excluded most of the organization’s employees from identifying the projects. Although we used this material extensively as corroborating evidence for our analysis and found that it was largely consistent with the interview data, we were unable to report direct quotes from this ‘highly sensitive and secret’ information in this manuscript. Some archival records © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies 524 D. A. Shepherd et al. were publicly available, such as company reports, company press releases, newspaper articles, trade magazines, and analyst reports. Again, although we used these data in the analysis, before quoting from these sources, we altered the content in a way that maintained anonymity for the project and the organization but still communicated the spirit of the information. In sum, this complementary data entailed about 450 pages of single-spaced field notes, internal reports, internal memos, and emails as well as press releases and newspaper articles that complemented and validated team member statements in the interviews (i.e., approximately 1303 pages of single-spaced data in total). Figure 1 provides an illustration of the multiple sources we used for data collection in this study (Figure 1a and b), which projects’ periods were covered by which data (Figure 1b), and the point in time when data were generated (Figure 1c). Data triangulation from different sources, the use of structured interview guides, and multiple site visits allowed us – to some extent – to address weaknesses inherent in interview data, such as retrospective and informant biases arising from the missing introspection of interviewees (Miles and Huberman, 1994). Data Analysis We approached the cases with an open mind (with knowledge of the literature but without preconceived propositions) to allow the data to speak to us (Suddaby, 2006). Following Yin (2008), we coded segments of each interview transcript that we identified as possibly being relevant to addressing the questions of context consistent with the purpose of the study – the contextual factors that link the speed of project termination and team members’ learning from project failures. Specifically, we classified segments and assigned them to nodes that emerged through the classification process. After reading and rereading the transcripts many times, we coded and recoded the data, identifying phrases and specific terminology until the classification system covered the material. We continued coding the transcripts in this manner until we were confident that the identified nodes (i.e., first-order categories) and sub-nodes (i.e., second-order categories) fully addressed the information the members provided. Although we began to notice similarities and differences across cases, we withheld drawing any inferences until all the coding was complete. The data were then organized into large tables such that the rows were the nodes, the columns were the cases, and the cells contained the corresponding segments of text. From this ‘raw’ table, we constructed a summary table. Again, the rows were the nodes and the columns were the cases, but this time, the cells represented assessments of the level of the specific node variable (e.g., whether learning was high or low) for the corresponding case. The assessments were conducted by one of the authors and an independent rater. The two raters had an initial percentage of agreement of 91.6 per cent with differences occurring predominantly at the ‘margins’ of the categories. The sources of disagreement were discussed until agreement was reached. We then used a cross-case comparison to allow differences across groups (i.e., high learners versus low learners) to emerge (Eisenhardt, 1989; Miles and Huberman, 1994). Specifically, we oscillated between the ‘raw’ table and the ‘summary’ table, which is consistent with moving our thinking between details and abstractions. As a result, the key constructs and their relationships began to emerge. © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies Creeping Death and Learning from Failure 525 FINDINGS: TIMING OF PROJECT TERMINATION AND LEARNING FROM FAILURE EXPERIENCES Learning from Project Experiences Details emerged from the data linking the timing of project termination to team members’ learning from the failure experience. In particular, we asked team members to reflect on how much they had learned. This approach is consistent with the sensemaking perspective on the importance of developing a plausible story in order to inform future actions (Weick et al., 2005). Although groups (i.e., organizations and teams) can learn (Fiol and Lyles, 1985), we focused on the outcome of individual team members’ learning from their experiences. Interestingly, we observed variance in learning levels both across and within subsidiaries. In Table II, we illustrate our initial grouping of cases based on learning levels for each case (project). In projects Alpha and Argon (subsidiary A), Cobalt (subsidiary C), and Dubnium (subsidiary D), the team members reported learning a great deal from their experiences. For example, the Dubnium project leader learned critical project management skills: ‘[In the future,] I would lead this project by keeping the team on a much “shorter leash”. . . . In such a project, I would bring people together as close as possible – in one place. . . . Also, I [learned] that we need to exchange people between sites more often. It simply doesn’t work if you know people only by having phone-contact – you must have a personal relationship.’ Further, we heard from a conversation between the project manager and team member 1 that as a result of terminated projects, the subsidiary manager had established a ‘lessons learned’ database, and they discussed specific lessons that had been entered into the database. In addition, internal emails and other field notes demonstrated that team members from project Cobalt expressed hope that the important lessons from this project would be translated to others. The high level of learning for each team member of projects Alpha, Argon, Cobalt, and Dubnium is in contrast to the low level of learning of each team member within projects Bravo and Boron, Charlie, and Delta. For example, all interviewees of projects Bravo and Boron stated that they did not generate any specific learning about how to manage R&D projects or how to improve the R&D process. Similarly, members of project Charlie attributed little learning to having had a project fail but suggested that learning occurred merely through generic work experience. They felt this experience had been obtained as it would have in any other circumstance. Team member 2 of project Charlie even went so far as to say, ‘This project was terminated due to a decision of the top management, not due to our mistakes. We didn’t make any mistakes [to learn from]; we are not bad engineers. We should be thanked.’ Members from these projects were also explicit in asserting that they would not be making changes following the failed project experiences. The leader of project Boron explained, ‘I will do it [future projects] in exactly the same way.’ The rest of this paper deals with our attempt to understand these differences in learning from failure, which generates new insights about the relationship between speed of project termination and learning from the experience. As the data led us to group the R&D cases based on learning levels, we then compared and contrasted across groups to help us understand why these groups experienced such different levels of learning. From © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies 526 D. A. Shepherd et al. Table II. Team members’ reflection on and learning from the terminated project Evidence of higher levels of learning Evidence of lower levels of learning Project/representative quotations Level Project/representative quotations Level Project Alpha Project leader: ‘The most important thing [I learned] about this open communication [about project termination] is to be honest. If you do not know something, it is best to say it right away than to “build castles in the sky”.’ Team member 2: ‘It is not only important to understand the headline but also the sub-items [details]. This became very, very clear during this project. . . . You can still find certain problems you have not thought of before. It has been very important learning from this.’ Project Argon Project leader: ‘[From this experience I learned] the first machine will always cost the most, and the more we build, the cheaper it gets. But our cost calculations were not able to consider this fact. This was one of the “lessons learned” from the project – that we have many weaknesses in the way we calculate product costs.’ Team member 1: ‘I personally have learned a lot from this. I’ve gained a lot of experience regarding the technical content, as well as when to communicate with the internal client and all involved.’ High High Project Bravo Project leader: ‘I am not always that good at learning from failure . . . I was fighting and fighting and fighting, and [reflecting now I see that] I was blind because I wanted the project to succeed. And that was the failure in itself . . . I had blinders on.’ Team member 1: ‘I don’t think we should have a website for sharing learning . . . I don’t think you should make much of it, just discuss it with people and move on [which is what we did].’ Low Low Project Cobalt Project leader: ‘I [personally] documented lessons learned . . . these included learning on how we do things internally, how we deal with third party designers and drafters . . . [it is important] to write it down to help the team, so I can say “we did not do this last time, so let us make sure we cover it this time”.’ Team member 1: [Taking time to reflect] was important and the reviews looking into issues needed to be held. We needed to understand what the problems were . . . We have learned a lesson . . . let us not do that again. Project Dubnium Project leader: ‘I have really learned a lot [as a result of this project] . . . I have learned that it is important to make decisions, no matter whether it is good or bad, because it is really important that the people have a guiding principle during the whole project. It is bad, when decisions are made only half-way or one wobbles around.’ Team member 1: ‘To avoid the mistakes and to learn from them, I started a burdensome task of documenting errors [as the project wound down]. I did this by creating an environment in which I automated unit tests . . . That is, if there is an error, you write a unit test, thus it ensures that this functionality. I have laboriously built up this unit test coverage here . . . This is a method by which I learned from it [the project].’ Team member 2: ‘I personally always have points [during and after projects] where I say, “I would want to do them differently next time,” I think the organization has learned something, which showed in the next project.’ High Low High High Project Boron Project leader: ‘[When the project was canceled] I didn’t think that much about project Boron; I thought about the new project . . . If I learned anything from this project it is that the way I do things is right.’ High Low High Team member 2: ‘Concerning how I relate to our company as an employee and how we do the projects, I would say no [whether he changed the way he worked on projects]. . . . So the recipe itself for how I perform projects will not change a lot.’ Project Charlie Team member 1: ‘From any project we gather experience. Bad experiences are also experiences . . . The most important thing is that we got experience from the project. I mean technical experience . . . For an experience, to get experience, I can get it from any project [succeed or fail].’ Med High High High High High High High Team member 2: ‘To me, it was not a disaster. I gained [generic] experience from this project and I developed new models as well as new data now . . . [to clarify], the learning was only the technical documentation.’ Project Delta Project leader: ‘I think, I have not learned that much . . . I actually was surprised [taken off guard] in this situation where the project was actually canceled. [Now] I’ll try and be a bit more prepared (for failure) . . . I am a bit unsure also [following the failure].’ Team member 1: [When asked if there was a post mortem or if he collected learnings he stated]: ‘Hmm, it is difficult for me to say. I can only tell you about the formal side – that all work was documented; a number of reports were prepared . . . But these were only pure technical reports – the results and the conclusion . . . [as a result of this project] there was no change in our department and I hope no change at headquarters as well.’ Team member 2: [Now] I am goal-oriented in determining how much energy I should invest [knowing it could lead to failure]. [Also], I would force the project to come to defined milestones. © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies Low Low Low Low Low Low Med Creeping Death and Learning from Failure 527 this activity, we found that there was a clear difference in the speed with which projects were terminated. Specifically (and as illustrated in Table III), we found that when a project had an abrupt termination (i.e., rapid termination), members of that project team appeared to learn less than when a project’s termination was drawn out over an extended period of time (i.e., delayed termination). This recognition prompted us to further explore the impact of project termination speed on team members – first in terms of emotional impact and second (as it emerged from the data) in terms of engaging in learning activities. Creeping Death: Negative Emotions from a ‘Stalled Decision’, Not ‘Loss of a Project’ In Table IV, we summarize our findings illustrating those team members’ negative emotional reactions to, what they believed, was a delay in project termination. Members from teams that had experienced delayed project termination appeared to experience greater levels of negative emotion than those with rapid project termination. Team member 1 from project Argon aptly described his experience with delayed termination as ‘creeping death’: ‘I guess it was good that at some point there was a definitive decision. To this day, it still causes people to shake their heads [in disbelief ] because it was such a creeping death.’ Although not all members of projects that experienced delayed termination used the term ‘creeping death’, they all expressed a sentiment consistent with it. Creeping death refers to a project that is on the path to being terminated, and while this likely outcome is known, the steps along the path to termination are small and slow, and the process is emotionally painful. The following statements (and in Table IV) illustrate this conceptualization of creeping death from the perspective of the people involved. First, in creeping death, the eventual project termination was expected for quite some time. For project Argon, team member 2 noted that the termination ‘was to be expected . . . , [and] this discussion was in meetings for some time. . . . I had already resigned myself [to the project’s termination].’ He noted that it was ‘perhaps two or three months from when I saw signs the project would fall until the decision actually came.’ Project Cobalt team member 2 further concurred, stating, ‘By the time the announcement was made, we knew what was happening; there was no surprise there, which is probably why I do not remember it [the actual announcement]. I do not remember the particular meeting [where the final decision was given] simply because it was an inevitability.’ The leader of project Alpha noted that the ‘shutdown was a kind of slow descent’. Dubnium team member 2, exasperated by six months of creeping death, explained that ‘The configuration itself would have likely taken weeks. Errors were still present, and it would have been a miracle to convince any customer that it really could work!’ Second, this delayed termination generated negative emotions. The Dubnium project leader expressed frustration with the lack of decision making and the ensuing uncertainty: ‘I personally fell in a real motivation gap. . . . [The six-month delay in the termination decision] hurt our development department very badly because we actually had finished development in the spring, and we wanted to know the new direction. We knew that we had the people here, and they could not be redeployed back to their home country [office], which would have been a waste of time and money anyway. This was a very, © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies 528 D. A. Shepherd et al. Table III. Speed of termination Higher learning, delayed decision-making cases Lower learning, rapid termination decision-making cases Nature of termination decision representative quotes Project Alpha Project leader: ‘It was not surprising that people no longer believed in the potential of the technology anymore. In the end it was kind of a slow decent.’ Speed Delayed Delayed Team member 1: ‘The termination was not an “event” where we met one afternoon and then had a clear picture of the world, but the termination was a process [. . .] escalated at the end, when a decision had been taken by the entire management hierarchy.’ Project Argon Project leader example: ‘There was not a defined end, but it was a gradual starvation . . . We had many conversations over time [management and customers] and then the CFO pulled the plug . . . We learned a lot during this [time when project was dying] about product cost management.’ Delayed Team member 1: ‘I attended regular team meetings [for updates], it was indicated several times the project would stop as an R&D effort, but then we realized “oh, it continues [as a customer development project] . . . there was a lot of back and forth . . . as I said earlier, it’s a creeping death . . . it [still] flames up.’ Project Cobalt Team member 1: ‘[During testing] we realized that there was something wrong with the performance in the product . . . This was the first concern . . . Then there was a whole series of reviews to talk about where the performance was going. Was it a build issue? Were we looking at leaks within the system? . . . This probably went on for five months, four months within the product for validation [before the project was terminated].’ Team member 2: ‘[After initially finding out the product didn’t work right] we had a period of trying to find out what was wrong because . . . we had to acknowledge the possibility that we aren’t always right. We spent quite a time doing follow up work to trying get to the bottom of it. But after some time the view was to [officially] stop the work.’ Project Dubnium Team member 1: ‘[Initially] we were told the project was put on hold for three months, it was reworked and the revised scope was discussed. At some point we asked “what happens next.” All actions had stopped at the time . . . At this point I personally did not know what would come next [for the project or otherwise].’ Team member 2: ‘I think it was in August last year. At that time, it was said the whole thing was to be put on hold for three months . . . Later the customer said “We’re going to take a break, we’ll stop for now, wait three months and then we’ll decide whether we should continue or not. During that nothing happened on our side.’ Delayed Delayed Delayed Nature of termination decision representative quotes Project Bravo Project leader: ‘[Bert] simply notified us by email . . . as it turns out it would be not so fantastic concerning the figures and at the same time we could see problems on the horizon of automating . . . I shifted quickly onto the project I’m working on now.’ Team member 1: ‘And [Bert] said “Well, we do not believe in that [the project] because of these problems, and we will terminate the project immediately . . . [I quickly moved on as] I had already started a couple of new things [projects].” ’ Project Boron Project leader: ‘Our top guy . . . said: “this is our strategic decision, we need [to stop the project]”. . . . I did not see it [the failure] coming and it was the first time that I’ve made a full stop. In my first email [prior to the CEO’s decision] I wrote: we have a soft stop [delay]. Then two days later I wrote another email saying: we have a hard stop. That was not good.’ Team member 1: ‘This was just a decision made high up in the system . . . [Suddenly] we said “We will not put any more money into this project [and it was all over].” ’ Speed Rapid Rapid Rapid Rapid Rapid Rapid Delayed Delayed Project Charlie Project leader: ‘I had discussions with the office and with my superior about it – if we cannot solve the technical problem, we cannot continue with the project. So they (quickly) decided to terminate the project.’ Rapid Rapid Delayed Team member 1: ‘The project manager informed us practically immediately [after management had come to a decision] that the costs of the development and product had been analyzed and that there is no reason to continue this project [so we stopped working] . . . additional money to complete documentation and prepare everything for the formal closing was not even allocated [as it just ended].’ Project Delta Team member 1: ‘Effectively, we had programmed for about six to nine months and had created specifications drawings [for the product]. And then it was said from one day to the other that the project is discontinued. The feeling, as I said, was that this came as a great surprise.’ Team member 2: ‘There was a day when it was suddenly rumored: “What, the project is stopped?” Then, perhaps an hour or two later, the project manager came and said: “Yes, the project is stopped” . . . this was not communicated in time, management should have told us “listen, there are problems with time and budget” or “we are going in the wrong direction.” Instead, top management simply said “no, there is nothing.” ’ Rapid Delayed Delayed Delayed © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies Rapid Rapid Rapid Creeping Death and Learning from Failure 529 Table IV. Decision to terminate the project and negative emotion Higher learning, delayed decision-making cases Lower learning, rapid termination decision-making cases Project/representative quotes NE Project/representative quotes NE Project Alpha Team member 1: ‘[After a lot of deliberation] we decided to definitively ramp down [but not terminate] this project . . . there were still open tests that needed to be completed . . . so you could see that it wasn’t really shut down . . . nevertheless, [the delay] was very hard.’ Team member 2: ‘The real point is that you suddenly have the feeling that you would really like to press the turn-off button and forget about the project . . . [but instead] you have to pay attention and continue working [on the failing project]. [This situation] was extremely bad as I had the feeling motivation is not only getting lost but is reversing completely.’ Project Argon Project leader: ‘The longer it went on [the delay], the more impossible the task was. . . . Certainly people were frustrated . . . (when the final decision was rendered) but emotionally I’d say it was like adding a scratch to an already battered car.’ Team member 1: ‘Ultimately, if the decision is that a project is not flying, then I can accept that. But I need a clear explanation, which was lacking and the late timing [of termination] was frustrating.’ High High Project Bravo Project leader: ‘[It cost me] One night’s sleep, I think [to get rid of any negative emotions]. That is because I think there were no implications to my working situation.’ Low Low High Team member 1: ‘It [the negative emotion] was just a small scratch – one or two or something like that [on a scale from 1–10]. . . . But it was not a deep frustration. . . . I had no problems.’ Low High High Project Boron Team member 1: ‘It was a three or four [on a scale from 1 to 10 for negative emotion] because it is just bad when something like this happens. But then quickly, the day after, I said: “Ok, now my task has changed, this is what I am doing from now on.’ Team member 2: ‘We talked a lot about it the day that we got the news [of termination], and when I left the office, I just actually left it behind. . . . When I coped with this – which in this case, I could do relatively quickly – I looked ahead.’ Project Charlie Project leader: ‘I’d rate the emotional impact [of the project termination] maybe a three [out of ten] . . . I mean if a project is not fulfilling the KPIs and objectives, we need to discuss how we should continue the project. And if the business case is so bad, it is not good for the business to continue with the project as we have to focus on other, better projects to start.’ Low Low Team member 2: ‘I was informed [of the project termination] by my line manager . . . It was not very difficult to explain [to me] because to me it was absolutely clear . . . All of us had been assigned to new projects with new tasks. There was no time to think a lot – we did not have “free time” because we had other tasks.’ Project Delta Team member 1: ‘It was said from one day to the other that the project was discontinued. [The announcement], as I said, came as a surprise . . . It is of course a pity that our organization lost so much money . . . but regarded purely objectively, the issue was checked off for me . . . It doesn’t haunt me today’ (Interviewee laughs). Low Team member 2: (Interviewee laughs) ‘I remember the [day of termination] very well. First I was not even shocked but wondering. My reaction was: “Aha, I get to go home now” . . . I said: “Okay, I have to think about it,” and then I went home. [I reacted this way] because I did not expect this news to be so abrupt. Suddenly there was nothing. It was said it is stopped, that’s all . . . [I was] in disbelief . . . [However there was some relief] as I definitely felt earlier that the project was actually too much work.’ Med Project Cobalt Project leader: ‘We were all worried about telling headquarters we had slipped a little bit. After some time our business decided to move the machinery around in the factory-every machine was moved. This compounded our problems . . . and meant I could not get my project going until the machines were moved. At this point, the penny finally dropped [in my mind] . . . I was disappointed that they did not come up earlier and explain “We are moving all machines, by the way you are in big trouble!” ’ Team member 2: ‘I felt sick. Yes, I felt absolutely awful. Yes, you know, it was just like a continuous stage fright type of situation [during the delayed termination] . . . Trying to put on a brave face for the family activity the next day sort of thing but really not feeling good at all . . . We were just down in that emotional pit [anticipating failure during the delay].’ Project Dubnium Project leader : ‘[While waiting for a decision] we lost half a year, in the sense that no one knew the direction the unit was heading . . . We had requirements, but no one knew which ones we should implement. As a result . . . we messed around for half a year . . . it really didn’t feel good.’ Team member 1: ‘[The project delay] was rather frustrating . . . of course this was frustrating in itself.’ Team member 2: ‘The project was pulled in October, but you had to ask constantly [about the status] . . . In October, we always thought “When will something happen?” Details were very sparse . . . There was a general lack of understanding, also irritation, why the decision and direction was not really communicated, and what the reasons were for the decision.’ High High High High High High High High Low Low Low M-L Low © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies 530 D. A. Shepherd et al. very bad situation.’ Team member 2 of project Argon commented that he felt ‘frustrated’ with the speed of termination and felt ‘relief ’ when it was finally over: ‘we had an incredibly long time with no definitive decisions, and at least this was a decision.’ Similarly, Argon team member 1 stated, ‘Ultimately, if the decision is that a project is not flying, then I can accept that. But I need a clear explanation, which was lacking and the late timing [of the termination] was frustrating.’ Project Dubnium team member 2 explained his frustration with what he viewed as wasted human and material resources during the creeping death: ‘My frustration, if you will, is that the project members are really good. A lot of people do really a very, very good job, and they are very committed. The fact that we don’t use them sufficiently and effectively and that we waste time with projects that drag on and ultimately we don’t pursue [is very frustrating].’ Indeed, the creeping death caused worry, not worry about the life of the project but worry about being held back from doing other projects or activities; there was a frustration that key human resources (themselves and others) were unnecessarily ‘tied up’. Project Alpha team member 2 explained, ‘As you can imagine, if you keep 20 of the best engineers you have and an extended team of 70 people occupied with such a project, they are not available for other problems and opportunities elsewhere in the organization.’ Our field notes corroborated the evidence mentioned above. For example, in several side conversations with interviewees (after the termination of the project), they repeatedly expressed the negative emotional impact of the delayed termination. In addition, internal emails between individuals (from when the projects were still in operation) confirmed both that the projects were delayed and that the delay was a primary cause of frustration and worry. Therefore, although we found that the final termination event (i.e., team members’ redeployment to other tasks) did not generate negative emotional responses, delayed termination did. Specifically, what is important to team members is not so much the project itself but the engineering challenge – the specific technical aspect of a project or job that the team member performs and that often relates to a team member’s fascination with the science behind potential products. For example, the project leader of Argon commented, ‘It was also satisfying when you design a machine and everything fits. So if the top was put on the machine, our machines are very large, several meters long and several meters in diameter, and you have gaps that are tolerated in tenths of millimeters . . . and everything fits. This is a great feeling. Therefore, this project was really satisfying for me.’ This demonstrates that what was important to him was solving engineering problems; whether the overall project survived or not was far less important. Another example of this phenomenon is noticeable in the description team member 1 of project Argon provided of the terminated project: ‘Ultimately, I believe that we have had a very good project here from a technical perspective: we have set a benchmark in the timeline we needed, we have gone through the product development process appropriately, we have involved all necessary parties.’ Finally, project Charlie team member 2 was indifferent to the failure of the project he was working on but expressed excitement with the engineering challenge: ‘[In my new project,] I get to focus on mathematics and developing algorithms. . . . This is a huge positive as I will be in my element.’ As Green et al. (2003, p. 423) noted, ‘innovators like to innovate; being on the leading edge of a technology can be both scientifically satisfying and ego gratifying.’ © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies Creeping Death and Learning from Failure 531 Consistent with this notion of the importance of the engineering challenge over the importance of the project outcome, we found that it was only when the ‘opportunity’ to work on important problems was denied that team members generated negative emotions. When a project was terminated, team members were quickly deployed to work on other tasks. For instance, many team members noted that their transition to another project was ‘immediate’. However, when the decision to terminate was delayed, the team members perceived this creeping death as being ‘stuck with’ working on an unimportant engineering question/problem. It appears that the engineers in our sample did not have a negative emotional reaction to project failure because they were still able to do what they love to do – offer technical solutions to the most challenging and current engineering problems (rather than the dead-end the failed project had become). In contrast, projects Bravo, Boron, Charlie, and Delta were terminated rather quickly – the decision to end the projects was unequivocal and final, and there was little time from expecting termination to actual termination. One team member explained project Boron’s termination by saying, ‘It was suddenly a reality.’ Project Charlie team member 1 believed that ‘the information [decision to terminate] was delivered abruptly to the team members – practically immediately. It was clear there was a decision to stop the project, so it meant that we should immediately stop spending money.’ When asked if he had anticipated a project shutdown, project Delta team member 2 responded, ‘Quite honestly, not directly. . . . I don’t remember any signs or timeline [red flags] indicating a possible termination. . . . I did not expect the decision to be so abrupt; suddenly there was nothing, and it was said “the project is stopped”, and that was it. . . . As a team, we were all surprised by the decision.’ Similarly, when asked about anticipating project Bravo’s termination, a team member replied, ‘No, not until I had this meeting. . . . And then I thought “Ok, then we have to terminate because we have no chance to get the material”. So we could not continue.’ As another point of contrast and as illustrated in Table IV, the team members of projects Bravo, Boron, Charlie, and Delta did not generate many negative emotions or worry even when we directly asked about it. For example, when asked about the duration of his emotional reaction to the termination, the project leader of Bravo reported that it cost him ‘One night’s sleep, I think. That is because I think there were no implications to my working situation.’ The project leader of Boron noted, ‘I am not that hurt by it. I now have another really big project.’ Project Charlie team leader said, ‘It was not necessarily fun to terminate the project, but we had to do it, and it was “business as usual” (laughs). . . . Really it was no problem.’ The Delta project leader explained, ‘I was also relieved’, a sentiment shared by Delta team member 2 as the stress of the project (e.g., meeting deadlines, etc.) was substantial.[1] Our field notes on site visit observations (after the termination of all projects), internal emails (prior and post project termination), and meeting minutes (prior to termination) substantiated our general finding that a majority of team members in projects Bravo, Boron, Charlie, and Delta experienced lower levels of negative emotions than team members on projects Alpha, Argon, Cobalt, and Dubnium. In these field notes, we recorded team members’ retrospective accounts of the absence of strong and lasting negative emotions both before and after the termination of projects Bravo, Boron, © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies 532 D. A. Shepherd et al. Charlie, and Delta (with one exception in which an individual was assigned to a project he viewed as less interesting). For example, in side conversations after the interviews, team members from these projects said (in reflecting on the terminated project) that they had no or little negative psychological or physical reactions to the terminations. That is, it was ‘no big deal’, and they simply focused on the new task at hand as opposed to reflecting on the recently failed project. Learning ‘Before’ rather than ‘After’ the Termination Event In this study we found that negative emotions stimulated rather than constrained learning from the failure experience. The source of the negative emotions was that the engineering challenge of the current project was diminished (given expectations of its ultimate demise) and these negative emotions stimulated the search for a new challenge – learning why the current project had failed – while they waited for the termination decision. Motivated to find a challenge, despite the creeping death of their current situation, team members dedicated time and effort to learning from failing projects before the termination event. For example, project Argon team member 2 explained that while enduring the negative emotions associated with the delayed termination, he took on a ‘neutral position, a position of an observer’ where he could think about what happened. Argon team member 2 further explained, ‘I’ve been thinking a lot about the project . . . I asked myself again and again how could it happen? . . . So I did learn [from this delayed termination].’ Similarly, Cobalt project team member 2 expressed his desire to enact some meaningful outcome from the delayed termination in spite of the negative emotions caused by the delay, specifically in identifying real, engineering, and hence business value from the experience. He explained ‘I think you feel very isolated [due to the failure] . . . [but] we have to learn from this, capitalize on it, get value from it . . . as long as people sweep it [project failure] under the carpet . . . we lose the opportunity to convert that bad experience into financial value, real business value . . . [normally] we are not good at closing projects out.’ Cobalt team member 2 similarly emphasized that this learning had to take place during the delay (or at least the life of the project) because ‘once the job stops, the reviews stop’. As a final example, Alpha team member 1 described the creeping death as ‘endless misery’ and would have preferred a ‘miserable end’ so he could ‘be staffed immediately, anywhere!’ to resume an engineering challenge. However, to compensate for being ‘trapped’ in a failing project this team member spent a lot of time making sense of and learning about what went wrong and how these learnings could be applied in the future. He explained that he ‘absorbed the termination’ by ‘documenting all our results . . . in an ordered manner so it all wasn’t just thrown away’. As a result, he learned that the decision to terminate was ‘dead right’. He explained that ‘if we really went, with the limited knowledge at that time, directly into a commercial project, then this would have cost our company, I think, a tremendous amount of money in the end.’ We found that the negative emotions generated by delayed project termination (i.e., creeping death) produced a positive outcome: it motivated the allocation of time and effort to learning from experiences with the failing project. This motivation to learn from © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies Creeping Death and Learning from Failure 533 the failing project becomes all the more important when there is a lack of time for team members to reflect on the project after the decision to terminate the project. The primary reasons for this lack of time to reflect appear to be threefold: (1) In nearly every case, project team members were rapidly redeployed after the official termination, forcing them to redirect their attention to starting new assignments, addressing new problems, and ramping up with new team members as opposed to reflecting on what went wrong with the previous project. For example, several team members were redeployed on other projects within several hours (e.g., project Boron team leader, project Charlie employee 2, project Cobalt team leader) while all others were redeployed within one to ten days with the exception of the project Delta team leader who waited about one month. (2) The project team members were motivated to move onto what was next to minimize role uncertainty, and they were anxious to use their competences to solve the next engineering challenge (given that the current failing project no longer represented an engineering challenge). For example, project Charlie employee 2 explained that the most important thing for him following a project failure is ‘to get a new task’. When asked how soon, he said without hesitation, ‘Immediately!’ (3) The combination of a desire to move on and the demand for work appeared to limit project team members’ ability to take the time after project termination to effectively process project failure and thus learn from it. Given this rapid redeployment after project termination for all team members of every project, the period provided by delayed termination took on increasing importance in terms of processing learning opportunities from the failing project. In Table V, we summarize evidence linking termination timing and learning from failure through the activation of key learning mechanisms (i.e., reflect, articulate, and codify; Prencipe and Tell, 2001; Zollo and Winter, 2002). First, members of projects with delayed termination (Alpha, Argon, Cobalt, and Dubnium) had time to reflect on their experience, which enabled learning. The leader of project Argon explained, ‘I personally learned a lot on the project . . . during the [six to eight months of the failing project]. . . . I was almost in the position of an observer, watching what we were doing and [reflecting] on “what exactly did we do here?” ’ Similarly, through his ‘introspective reflection’, team member 1 of project Alpha identified specific lessons he would apply to future projects. He explained, ‘[During this period of delayed termination,] everyone evaluated his experiences and drew conclusions, for example what he would do next time in the same way or what he would do differently. I personally learned that I would deal with the customer differently next time.’ Second, delayed termination provided the opportunity for team members to articulate learning experiences with fellow team members. Setting up forums for team members (in many cases from around the world) could be a challenging and expensive task, especially when a project concluded and there is no longer a profit-driven rationale for the team to stay together. However, given an environment in which termination was inevitable yet delayed, team members took the opportunity to hold meetings that allowed them to articulate their learning experiences. Cobalt team member 1 explained that his team held many intensive ‘reviews’ during the delayed termination, attempting to identify the ‘root cause’ of why the product was not working. He explained, ‘We held a whole series of reviews to talk about where the performance was going. Was it a build issue? Were we looking at leaks within the system? . . . This probably went on for four to five months.’ © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies 534 D. A. Shepherd et al. Table V. Termination speed and learning Higher learning, delayed decision-making cases Lower learning, rapid termination decision-making cases Learning in relation to termination speed representative quotes Learning Learning in relation to termination speed representative quotes Learning Alpha Team member 1: ‘We decided to at least document all our results. But I must admit, in the end it would have been great to have even more time to document things the way we wanted to do it . . . [During the delay] I learned that it would have been better to invest more in exploratory research at the beginning.’ High High: During delay Low Low Team member 2: ‘[We captured learning during the delay] otherwise there is the risk that you throw away what you have laboriously attained. A project can become worthless if you do not pay attention . . . I not only requested [the time to prepare the documentation] but I also got it . . . So damage [in losing learnings] did not occur.’ Argon Project leader: ‘The project was between life and death. It was not yet dead, but it was also not properly alive . . . I personally learned a lot on the project . . . during the [6-8 months of “failing”] . . . I was almost in the position of an observer, watching what we were doing and [reflecting] on: “what exactly did we do here?” ’ High: During delay Bravo Project leader: ‘[After the announcement that the project was terminated] I moved onto a new project . . . it was business as usual more or less, we are used to Bert’s sharp decisions, “digital decisions” as we call them . . . We just have to move on from the failure, and then we work and work and work and work and there is nothing but work to do. So we do not ask so many questions, if there was a failure we simply say – “Ok, up on the horse again.” ’ Team member 1: ‘[When Bert announced the decision regarding the project failure] I had already started a couple of new things . . . this was very interesting to me and my colleagues here [to immediately work on new assignments] . . . I would not say I had key learnings.’ Team member 1: ‘By this slow death one would have lost a lot of time if you would want to continue the project . . . [However, due to the slow death] I had enough time for this [documenting the lessons learned] because I was appointed to . . . initiate process improvements . . . this took a few months during which we regularly discussed what we could do better.’ Cobalt Project leader: ‘Lessons learned? I got those together [myself] . . . Because it is not a formal process, I am trying help myself learn and help the next team I was assigned to with learnings from this current project . . . [during the delay] I documented learning related to internal decision processes and how to work with third party design houses and drafters.’ Team member 2: ‘[This project] was an enormous learning experience, certainly . . . [During the delay] we improved the knowledge of our product, I would say. So you know, we now got a clearer idea of what the beast [complex product] is, that we are trying to work with and what we can do rather than what we should avoid . . . But [after the termination] the formal documentation everything stopped . . . after that I was not involved in anything.’ Dubnium Project leader: ‘We have processes in the development. We make a post-mortem meeting for each development project where the input of the team is collected. We ask “What was good? What was less good? What would you recommend other projects as an outlook?” This happened for us as well, at least immediately after the date in February, it was, I believe, in March and April 2010 [months before the final decision to terminate in November].’ Team member 2: ‘[A big thing I learned during the delay] is that we lacked appropriate contact with the customer . . . If we do this though we will have more information on what they need and they will have more information on what we do [to help avoid a failure like this one].’ High High: During delay High: During delay High High: During delay Boron Project leader: ‘[Eight days after the termination] I am focusing more on my new assignment. I knew it would be a short time between projects and (the new project) came up very fast . . . My boss called me and said “hey, we have tons of work for you to do. Just jump out of that project and then you can focus on this [your new assignment]. This was very helpful.” ’ Team member 2: ‘We got a note from business that this project was stopped. The end . . . I re-motivated myself by looking ahead, telling myself that in this case there was simply nothing I could do about the project failure . . . as for me I was already reassigned before this project officially ended [so I am focused on that] . . . this was the case for all people on my team.’ Charlie Project leader: ‘It is very hard to [learn from failed projects] . . . there are good intentions but it doesn’t work . . . employees have so many other things to do . . . we had no problem reallocating our people and remaining budget to interesting projects [which became the primary focus].’ Low Low Low Low Low Low High: During delay Team member 2: [Interviewer – Do you document anything to learn – e.g., lessons learned for future projects?] ‘No, we only create the technical documentation . . . [in fact] I think a new task is the best action moving forward . . . It is best to [quickly] assign people to a new job . . . we were all assigned to new projects with new tasks. There was no time to think- we did not have “free time” because we had other tasks [new projects].’ Low High High: During delay Delta Project leader: ‘[A project write up] is normally at the end of a project, where we write up a little something, these are one to two pages on the reason the project has been canceled. But it was really just a compilation of the results actually . . . but as soon as we saw a new task on the horizon [which was quite rapidly] it is important to immediately throw yourself into it.’ Low Low High: During delay Team member 1: ‘No one asks about [the failure] actually, no one would know about it anyway and I don’t think that one somehow goes peddling the learnings from the failed project . . . the most important thing that happened . . . was that we were allocated to other projects within a few days.’ Low © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies Creeping Death and Learning from Failure 535 Finally, delayed termination provided the opportunity for team members to codify key learning experiences via lessons learned documents, Excel spreadsheets, database uploads, or other media of choice. As a specific difference to documentation undertaken by some of the projects with low learning, members from projects with high learning documented information focusing on explanations of project outcomes (i.e., why and how the project did not work out) as opposed to descriptions (i.e., what happened, as in money and time spent, etc.). The Argon project leader explained the value these documents provided his team: ‘We found that in essence, it [the time taken to capture lessons learned] is about facts that can be written down for why something did not work. To document that we have used a specific design for the product, why it didn’t work, and what we should have considered in our design. Thus, in the next design phase, colleagues can benefit from the learning and do not have to have the same experience themselves.’ In contrast, for project teams Bravo, Boron, Charlie, and Delta, there was little time for reflection on, articulation of, and codification of learning due to the rapid project termination and subsequent redeployment to new projects. For example, team members from these projects expressed a lack of time to reflect on their experience as explained by one of our interviewees during a joint business lunch: ‘[I did not have] sufficient time to process and document the lessons learned from the terminated project because [after the rapid termination of the project,] I was immediately transitioned to a new project due to the large pipeline of development projects in the firm.’ Rather than having time to reflect on what went wrong, it appeared that when a project was terminated with little warning, team members needed all their cognitive capacity to prepare for and cope with the demands of the new project. Team member 1 of project Boron noted that the transition happened rapidly: ‘the day after [the termination], I just said, “Ok, now my task has changed. I need to do this for that [new project], and this is what I am focusing on now”.’ Members from projects that were rapidly terminated also expressed a lack of opportunity to articulate potential learning experiences from the failed project. The Boron project team leader explained, ‘I would say here at our location, we did not share [lessons learned].’ This lack of opportunity to articulate learning and lack of evidence of learning from the project experience in general was evidenced by several interviewees (i.e., Charlie employee 1, Delta employee 2, Boron employee 1) expressing gratitude for having the chance to sit down and discuss the project and potential lessons learned with the interviewer, explaining that this really was the first time they had been able to reflect on the project failure and its implications. When asked if he would have appreciated doing this earlier with his team, Charlie employee 2 said, ‘Yes, absolutely!’ Furthermore, members from projects Bravo, Boron, Charlie, and Delta did not have the opportunity to effectively codify lessons learned. While several team members mentioned documenting the ‘basics’ – a description (as opposed to an explanation) of the project for record-keeping purposes (e.g., Delta project leader, Charlie team member 1 and team leader), they were explicit that this was simply to track the ‘technical’ aspects of the project, including ‘how much money was spent’ (Charlie project leader) and ‘mathematical results’ (Delta team members 1 and 2). In other cases, however, team members explicitly cite the lack of any documentation. Project Boron team member 1 explained, ‘I haven’t really met anybody who said “Well, make sure if something goes wrong that we document it, that we learn from it, and that we somehow inform others”. © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies 536 D. A. Shepherd et al. Learning before failure Creeping death Speed of termination Delayed Learning from project failure Negative emotions Rapid Cognitively moving away Emotionally moving away Figure 2. A double-edged sword of delayed project termination I have not seen that. . . . There is this saying that I have heard: “If only our company knew what our company knows”.’ The literature acknowledges that individuals can learn from their failures – perhaps even more than from their successes (Sitkin, 1992) – because a failure indicates that current knowledge structures were inadequate, which can motivate sensemaking activities (Ginsberg, 1988; Morrison, 2002). That is, after the termination event, the individual can reflect on and cognitively process his or her experiences and work to construct a plausible account for the failure and thereby learn (Shepherd et al., 2011; Weick et al., 2005). Rather than time after project failure being critical for learning from project experiences, our findings suggest that the time provided by the delayed termination is important in explaining who learns from project experiences and who does not (or who learns less). This is because under conditions of rapid redeployment after project termination, delayed project termination provides the time (and motivation) for team members to learn from a failing project by facilitating (a) reflection on the experience, (b) articulation of lessons learned, and (c) codification of lessons learned, that they would not have otherwise. DISCUSSION We found that delayed termination was like a double-edged sword (as illustrated in Figure 2). On one side of the sword, delayed termination was perceived as creeping death that generated negative emotions among individuals who were (for the most part) more emotionally invested in the engineering process than in the specific project. On the other side of the sword, delayed termination provided time for reflection, articulation, and codification for learning from the project experience. In contrast, for those whose projects were rapidly terminated there was little negative emotional reaction to the © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies Creeping Death and Learning from Failure 537 project failure and little learning from the experience because team members emotionally and cognitively moved away from the previous project towards their new engineering challenge. In this study, we contribute to the scholarly conversation on learning from failure and on the implications of the timing of project termination by exploring the contextual factors that help explain the link between speed of termination (i.e., delayed or rapid) and learning from the failure experience. Research has identified the cognition underlying the timing of the decision to terminate poorly performing projects (Ross and Staw, 1993; Staw and Ross, 1987) and its organizational learning implications (Corbett et al., 2007). Although these studies have deepened our understanding of those who decide on project termination (i.e., who ‘own the option’), they do not explore (because it is not their purpose) the contextual mechanisms that link timing of termination to the reactions of those working on the project (i.e., those who ‘are the option’; McGrath et al., 2004). Our analysis, findings, and theorizing offer an initial step in this direction. In doing so, we make contributions to the literature on both learning from failure and project termination. Learning from Failure: Negative Emotions and the Timing of Project Termination In this study, we provide insight into the link between the timing of project termination and learning from failure from the perspective of those working on the project (i.e., project team workers), which has implications for managing entrepreneurially acting firms. First, team members reduce the negative emotions over project failure through an engineering mindset. The engineering mindset focuses more attention on the criticality of the engineering challenge for the organization than on any one project. With this engineering mindset guiding attention, project failures generate little negative emotion, and there are few obstacles to the rapid redeployment of resources (including human) to the next project. However, if that transition is delayed (from the project team members’ perspective), team members generate negative emotions. Interestingly, such team members generate negative emotions when a (poorly performing) project is not terminated rather than when it is terminated. Overall, an engineering mindset is not only a cognitive script for creatively solving problems, but it also emphasizes the importance of the engineering process of undertaking challenging tasks of significance to the organization over and above commitment to a specific project that is no longer of high importance to the organization. Second, delayed termination provides time for team members to reflect on personal mistakes (i.e., missteps in a particular process, miscalculations, etc.), organizational issues (i.e., management decisions that led to failure, inter-department coordination problems, etc.), technical issues (i.e., technical problems from an engineering perspective), and market- or industry-related issues (i.e., institutional or governmental influence in product development, customer participation, etc.). Such reflections provide a basis for lessons learned that could be articulated and codified with sufficient time, two steps necessary for organizational learning (see Zollo and Winter, 2002). In contrast, team members who face rapid project termination have little time to learn from their experiences with project © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies 538 D. A. Shepherd et al. failure. This is particularly problematic in an organizational context of rapid redeployment because after project termination, there is no time to reflect on, articulate, and codify lessons learned from the failure experience. Indeed, even if project team members find some time to reflect on the project failure, they do not have time to share those reflections with others – which obstructs team-level learning – nor do they have the time to codify any lessons learned – which obstructs organization-level learning. Thus, the interesting insight is that in the context of rapid redeployment, individual team members, teams, and organizations largely do not learn from their failure experiences after the failure event but before it. Finally, team members use negative emotions from creeping death to motivate learning from failure. This use of negative emotions is effective for learning because it signals to team members that something is wrong, that the organization no longer values the project, and that redeployment to a more important engineering problem is being delayed. Team members are able to direct these negative emotions from the thwarted need for an important engineering challenge to a new challenge while they wait – the challenge of learning from failure. By shifting attention from the delay (and thwarted need), they are able to learn from the experience. Therefore, the negative emotions of creeping death facilitate rather than obstruct learning from failure. In sum, our team members’ perspective highlights individuals’ reactions to the timing of project termination for learning from project failure. Namely, in the context of creeping death, team members are able to (1) reduce negative emotions over project failure by emphasizing the importance of the engineering challenge vis-à-vis any one project; (2) provide time for team members to reflect on, articulate, and codify lessons learned (in the context of rapid deployment, this time comes before termination); and (3) redirect negative emotions from creeping death to the challenge of learning from the failure experience. Rethinking Portfolio Management and Corporate Entrepreneurship Theories of portfolio management and corporate entrepreneurship are central to extant efforts to link project termination (and the timing thereof) to learning from failure. The insights generated from this study provide the opportunity to contribute to both these streams of research. First, the findings provide a deeper understanding of the interrelationship between the main components of portfolio management. We reaffirm the importance of managing uncertainty by creating projects as options (McGrath, 1999) or probes (Brown and Eisenhardt, 1997) that explore the unknown. Under these conditions, exploration efforts can help improve overall performance when poorly performing projects are rapidly terminated and resources are rapidly redeployed to projects that show promise and/or to new projects (Brown and Eisenhardt, 1997; McGrath, 1999). However, the insights from this study suggest that rather than learning from a project that has failed, team members learned from their experiences with a poorly performing project before it is terminated. Specifically, although failures are expected to capture project members’ attention and motivate them to make sense of the experience (Chuang and Baum, 2003; Sitkin, 1992), we did not find evidence supporting this conventional wisdom. Our findings suggest that because all team members were rapidly redeployed © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies Creeping Death and Learning from Failure 539 after project failure, they were not motivated and did not have the time and cognitive capacity to reflect on what went wrong and how things could have been done differently. This relationship between speed of termination and learning from failure has implications for the portfolio and real options reasoning perspectives for managing innovation projects. An implicit mechanism of managing uncertainty using R&D projects as options or probes is that they reveal information that contributes to new knowledge, including learning from project failure (McGrath, 1999). Indeed, real options reasoning advocates for (1) rapid termination of failing projects, (2) rapid redeployment of human resources, and (3) learning from project failures (Brown and Eisenhardt, 1997; McGrath, 1999; McGrath and Cardon, 1997). Based on our findings reported above, we propose that an organization can have two but not all three of these attributes. That is, an organization can rapidly terminate a failing project and rapidly redeploy human resources, but learning from failure will be limited. Alternatively, team members can learn from the project failure experience when termination is delayed. Specifically and consistent with real options reasoning (McGrath, 1999), in the R&D organization of this study, delay in project termination was considered costly by the parent firm’s management, the subsidiaries’ management, and especially those directly involved in the projects’ operations. Similarly, delay in resource (particularly human resource) redeployment was resoundingly deplored by those involved in the projects. However, the novelty of our findings is they show that in a context in which team members are quickly reallocated to new tasks once a project team is finally dissolved, some termination delay does come with benefits as it provides time (and motivates) reflection on, articulation of, and codification of lessons learned from project experiences. Although our data do not have variation in the speed of human resource redeployment (i.e., it was rapid in all cases), we suspect – and hope future research investigates – the possibility that rapid termination and learning are possible when human resource redeployment is delayed. Given that learning is crucial to R&D-intensive organizations (Hoang and Rothaermel, 2005; McGrath, 1999), our findings underline the importance of complementing the current focus on the immediate financial impact of delayed project termination with a more long-term learning perspective to better capture the effects of project termination on organizational outcomes. Second, our findings contribute to theories of corporate entrepreneurship, specifically complementing those related to cognition. Although we reaffirm the importance of the timing of the project termination decision for learning from the experience, we take the perspective of those who work directly on the project. In prior research, the decision makers’ perspective is of primary concern and the implications for those individuals or their organizations are investigated (McGrath, 1999; Royer, 2003; Sitkin, 1992). For example, in investigating how corporate entrepreneurs approach project failure through various cognitive scripts (linked to organizational-level rules and procedures), Corbett et al. (2007) found that when decision makers terminate projects without a developed understanding of critical market and organizational factors (i.e., ‘undisciplined termination’) or when project leaders keep a project in the system too long with little to no tie to strategic outcomes (i.e., ‘innovation drift’), learning is stunted. In contrast, they found that those who terminated projects in accordance with market and strategic goals (i.e., ‘strategic termination’) were more able to learn about the organizational and market factors needed to drive future success (Corbett et al., 2007, p. 838). This approach has © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies 540 D. A. Shepherd et al. enhanced our understanding of the cognitions and ‘termination scripts’ of those who make decisions on whether and when to terminate projects, particularly in terms of how learning from failure can benefit firms’ capabilities in other areas (Corbett et al., 2007). Similarly, in the terminology of a real options reasoning approach to entrepreneurship (e.g., McGrath, 1999; McGrath et al., 2004), previous research has focused on the ‘owner of the option’, yet those who ‘are the option’ are likely to have different reactions to the timing of project termination. By taking the perspective of the project team members – those who are not the project termination decision makers – we gain an appreciation of the frustration (and other negative emotions) team members feel over what they believe is a delayed decision to terminate the project. That is, we contribute to the implications of decision makers’ termination scripts (Corbett et al., 2007) on the interpretation and emotional reactions of non-decision makers involved in the project. This analysis suggests that decision makers and project team members differ on the ‘appropriateness’ of the timing of project termination and that these differences impact the extent to which team members learn from the experience. The key take away is that if team members perceive a subsidiary manager is taking too long to terminate a project, they have a negative emotional reaction and also take this opportunity to learn from their experience. Finally, the literature on loss suggests that most people will have negative emotional reactions to the loss of something important (Archer, 1999), such as the losses associated with divorce (Kitson et al., 1989), death of a loved one (Archer, 1999), and bankruptcy (Shepherd, 2003). Similarly, Shepherd et al. (2011) recently found that research projects are important to research scientists and that they have negative emotional reactions to these projects’ failure. Despite expectations based on the literature that R&D projects are important to team members and that their termination would generate negative emotions, this was not the case in the current study: all team members for all projects had minimal negative emotional reactions to the loss of the project specifically. A possible explanation for this lack of negative emotional reaction to the termination event is that the team members had become desensitized to failure (either through experiencing many failures or operating in an organization that normalizes failure; Ashforth and Kreiner, 2002; Shepherd et al., 2011), but our data suggest something different. Although failure was not considered normal for the engineers in our sample, transitions from one project to the next were. When transitions are considered normal, a delayed transition can be considered non-normal and is likely to generate a negative emotional reaction. Indeed, this is what we found in the current study: project team members were prepared for transition but had a negative emotional reaction when this transition was delayed. So, rather than attributing the lack of negative emotions from project failure to normalization, this lack of negative emotions could be attributed to an ‘engineering’ mindset of moving from one project to the next. The advantage of this engineering mindset is that project team members are unlikely to advocate for the persistence of (or escalation of commitment to) a poorly performing project, and negative emotions are unlikely to obstruct their ability to learn from failure experiences. However, consistent with criticisms that small wins may not be large enough to capture sufficient attention (Sitkin, 1992), this mindset towards project failure is unlikely to result in sufficient attention being allocated to learning from © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies Creeping Death and Learning from Failure 541 project failure after the actual termination is over. More research is required to investigate the role of individuals’ mindsets (with a focus on projects or process) in understanding the extent of the negative emotional reactions to a lack of (or delay in) change, such as feelings of creeping death. For example, empirical research can investigate whether engineers (self-selected and trained engineers as in the current study) focus more on process whereas scientists (self-selected and trained as in Shepherd et al., 2011) focus more on specific projects. Boundary Conditions and Future Research As with most case study research, we selected cases that facilitated theory building but also provided some boundary conditions for our model. First, we focused on R&D project termination. It is unclear whether the model will extend to other projects, such as joint venture projects, service-related projects, or projects focused on the implementation of a new product launch. Second, our cases involved engineers within subsidiaries within a parent organization that had an ‘engineering’ mindset. There is some doubt that our model will extend to all individuals with different (i.e., non-engineering) backgrounds or organizational cultures. For example, would a team of lawyers working on a death penalty case have such little emotional reaction to project failure and an eagerness to move on to the next death penalty case? Do biochemists, management consultants, architects, and academics have similar emphases as these engineers? Subsequent research designs could incorporate additional contexts and settings like these (including those mentioned in the first point) and could draw upon our theorizing and qualitative foundation when developing questionnaires or other means for obtaining cross-sectional or longitudinal data for analysis. Third, the individuals in the current study had alternate attractive opportunities to ‘move on to’ after their projects were terminated. Perhaps their reactions to delayed termination and project failure would be different if alternate projects were unattractive or non-existent. Fourth, we investigated eight project failures within four subsidiaries of one multinational corporation. It is unclear how the comparison between the four organizations (i.e., subsidiaries) would be different without the parent umbrella. Perhaps, for example, differences in the contextual factors between organizations would be greater than between the subsidiaries studied here. Fifth, we relied primarily on self-reports of learning as evidence of learning during delayed termination (consistent with the sensemaking perspective’s emphasis on individuals constructing plausible stories of events). Our theorizing does not necessarily extend to learning that results in increased accuracy or improved performance. Certainly future research could address these issues. Sixth, we took a relatively coarse-grained perspective of emotions. Future research can extend this boundary condition with a finer-grained exploration of the antecedents and consequences of specific emotions, such as frustration over delayed failure and relief when it is eventually terminated. Seventh, we investigated the consequences of delayed termination, not its antecedents. Future research can move beyond the notion of the escalation of commitment to explain © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies 542 D. A. Shepherd et al. heterogeneity in termination delay including the organizational context; the attitudes, cognitions and decisions to top management, and the organizational processes, systems, and norms that increase termination delay. Finally, our analysis and theorizing focused on individual team members. The individual level of analysis provides insights into the early stage of organizational learning, namely intuiting – the ‘recognition and/or possibilities inherent in a personal stream of experience’ – and interpreting – ‘the explaining through words and/or actions of an insight to one’s self and to others’ (Crossan et al., 1999, p. 525). To gain a deeper understanding of the link between project failure (and its timing) and organizational learning from failure, future research can explore the mechanisms underlying integrating – ‘developing shared understanding among individuals and taking coordinated action through mutual adjustment’ – and institutionalizing – ‘the process of ensuring that routinized actions occur’ (Crossan et al., 1999, p. 525), which is likely facilitated by (and contribute to) absorptive capacity (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990). Our findings that team members engage in articulating and codifying lessons learned from their experience (see Zollo and Winter, 2002) provide some evidence that research at the group and organizational level (and across levels) will make further contributions to the literature. CONCLUSION This paper explored learning from projects that had been terminated in the context of R&D-intensive subsidiaries of a multinational organization. Although scholars have acknowledged the link between the decision of when to terminate a project and organizational outcomes, including learning from failure, these studies have focused on decision makers’ cognitions. In this paper, we take a different perspective – that of the project team members impacted by the decision – which provides a number of counterintuitive insights. Rather than a desire to persist with a poorly performing project, team members perceive delayed termination as creeping death; rather than having negative emotions over project failure, team members experience negative emotions over delayed termination that thwarts their ability to move on to the next engineering challenge; and rather than negative emotions obstructing learning, the negative emotions of creeping death motivate learning from experience before a termination event. Based on the above, project team members’ reactions (cognitive and emotional) to the timing of the decision to terminate their project are likely to play a greater role in future research on learning from failure. NOTE [1] While a majority of the team members in the rapidly terminated projects expressed a lack of negative emotions relating to the event, three individuals did express some negative emotion, although it appears this was due to those team members’ unique circumstances. Team member 1 of Boron, for example, explained that his emotional reaction had more to do with his reassignment, which required that he and his family relocate to a different continent. It was moving his family that caused anguish, not the terminated project per se. Similarly, the Delta project leader was frustrated for reasons other than the project termination. First, he was upset that his next project was in ‘basic research’ whereas he was more © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies Creeping Death and Learning from Failure 543 interested in new product development, and second, he saw that the company restarted this project in another division only a year later (which also failed) and was ‘annoyed’ the company had not learned. Finally, project Delta team member 2 experienced some negative emotions but was explicit in providing a ‘historical context’ for those emotions. He explained, ‘perhaps I need to more deeply explain my past professional life [to explain why I reacted how I did]’, whereupon he described being part of two failed entrepreneurial firms before moving to Subsidiary D in the hope of finding more stability. His negative reaction appeared to be primarily due to this unique series of events, not the specifics of project Delta’s termination. REFERENCES Allen, N. J. and Meyer, J. P. (1990). ‘The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization’. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63, 1–18. Anderson, C. J. (2003). ‘The psychology of doing nothing: forms of decision avoidance result from reason and emotion’. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 139–67. Ansic, D. and Pugh, G. (1999). ‘An experimental test of trade hysteresis: market exit and entry decisions in the presence of sunk costs and exchange rate uncertainty’. Applied Economics, 31, 427–36. Archer, J. (1999). The Nature of Grief: The Evolution and Psychology of Reactions to Loss. London: Routledge. Arkes, H. R. and Blumer, C. (1985). ‘The psychology of sunk cost’. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 35, 124–40. Ashforth, B. E. and Kreiner, G. E. (2002). ‘Normalizing emotion in organizations: making the extraordinary seem ordinary’. Human Resource Management Review, 12, 215–35. Bower, G. H. (1992). ‘How might emotions affect learning’. In Christianson, S.-A. (Ed.), The Handbook of Emotion and Memory: Research and Theory. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 3–31. Brockner, J. (1992). ‘The escalation of commitment to a failing course of action: toward theoretical progress’. Academy of Management Review, 17, 39–61. Brown, S. L. and Eisenhardt, K. M. (1997). ‘The art of continuous change: linking complexity theory and time-paced evolution in relentlessly shifting organizations’. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 1–34. Cannon, M. D. and Edmondson, A. C. (2001). ‘Confronting failure: antecedents and consequences of shared beliefs about failure in organizational work groups’. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22, 161–77. Cannon, M. D. and Edmondson, A. C. (2005). ‘Failing to learn and learning to fail (intelligently): how great organizations put failure to work to innovate and improve’. Long Range Planning, 38, 299–319. Cardon, M. S. and McGrath, R. G. (1999). ‘When the going gets tough . . . Toward a psychology of entrepreneurial failure and re-motivation’. In Reynolds, P., Bygrave, W. D., Manigart, S., Mason, C. M., Meyer, G. D., Sapienza, H. J. and Shaver, K. G. (Eds), Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research. Wellesley, MA: Babson College Press, 58–72. Chuang, Y. T. and Baum, J. A. C. (2003). ‘It’s all in the name: failure-induced learning by multiunit chains’. Administrative Science Quarterly, 48, 33–59. Clinebell, S. K. and Clinebell, J. M. (1994). ‘The effect of advance notice of plant closings on firm value’. Journal of Management, 20, 553–64. Cohen, W. M. and Levinthal, D. A. (1990). ‘Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation’. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, 128–52. Cooper, R. G. (2008). ‘Perspective: the Stage-Gate (R) idea-to-launch process-update, what’s new, and NexGen systems’. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 25, 213–32. Cope, J. (2011). ‘Entrepreneurial learning from failure: an interpretative phenomenological analysis’. Journal of Business Venturing, 26, 604–23. Corbett, A. C., Neck, H. M. and DeTienne, D. R. (2007). ‘How corporate entrepreneurs learn from fledgling innovation initiatives: cognition and the development of a termination script’. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31, 829–52. Crossan, M. M., Lane, H. W. and White, R. E. (1999). ‘An organizational learning framework: from intuition to institution’. Academy of Management Review, 24, 522–37. Cyert, R. M. and March, J. G. (1963). A Behavioral Theory of the Firm. Englewood Hills, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Dixit, R. K. and Pindyck, R. S. (2008). Investment Under Uncertainty. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Dweck, C. S. and Leggett, E. L. (1988). ‘A social cognitive approach to motivation and personality’. Psychology Review, 95, 256–73. Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). ‘Building theories from case study research’. Academy Management Review, 14, 532–50. © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies 544 D. A. Shepherd et al. Eisenhardt, K. M. and Graebner, M. E. (2007). ‘Theory building from cases: opportunities and challenges’. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 25–32. Ellis, S. and Davidi, I. (2005). ‘After-event reviews: drawing lessons from successful and failed experience’. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 857–71. Estrada, C. A., Isen, A. M. and Young, M. J. (1997). ‘Positive affect facilitates integration of information and decreases anchoring in reasoning among physicians’. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 72, 117–35. Fiol, C. M. and Lyles, M. A. (1985). ‘Organizational learning’. Academy of Management Review, 10, 803–13. Frank, M. G. and Gilovich, T. (1989). ‘Effect of memory perspective on retrospective causal attributions’. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 399–403. Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). ‘Cultivated emotions: parental socialization of positive emotions and self-conscious emotions’. Psychological Inquiry, 9, 279–81. Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). ‘The role of positive emotions in positive psychology – the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions’. American Psychologist, 56, 218–26. Fredrickson, B. L. and Branigan, C. (2005). ‘Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thoughtaction repertoires’. Cognition & Emotion, 19, 313–32. Garland, H., Sandefur, C. A. and Rogers, A. C. (1990). ‘De-escalation of commitment in oil-exploration: when sunk costs and negative feedback coincide’. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 721–7. Gilbert, C. G. (2006). ‘Change in the presence of residual fit: can competing frames coexist?’. Organization Science, 17, 150–67. Ginsberg, A. (1988). ‘Measuring and modeling changes in strategy: theoretical foundations and empirical directions’. Strategic Management Journal, 9, 559–75. Gong, Y., Law, K. S., Chang, S. and Xin, K. R. (2009). ‘Human resources management and firm performance: the differential role of managerial affective and continuance commitment’. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 263–75. Green, S. G., Welsh, M. A. and Dehler, G. E. (2003). ‘Advocacy, performance, and threshold influences on decisions to terminate new product development’. Academy of Management Journal, 46, 419–34. Guler, I. (2007). ‘Throwing good money after bad? Political and institutional influences on sequential decision making in the venture capital industry’. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52, 248–85. Hoang, H. and Rothaermel, F. T. (2005). ‘The effect of general and partner-specific alliance experience on joint R&D project performance’. Academy of Management Journal, 48, 332–45. Isen, A. M., Daubman, K. A. and Nowicki, G. P. (1987). ‘Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving’. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 1122–31. Kahneman, D., Slovic, P. and Tversky, A. (1982). Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. New York: Cambridge University Press. Kiesler, S. and Sproull, L. (1982). ‘Managerial response to changing environments: perspectives on problem sensing from social cognition’. Administrative Science Quarterly, 27, 548–70. Kitson, G. C., Babri, K. B., Roach, M. J. and Placidi, K. S. (1989). ‘Adjustment to widowhood and divorce: a review’. Journal of Family Issues, 10, 5–32. Masters, J. C., Barden, R. C. and Ford, M. E. (1979). ‘Affective states, expressive behavior, and learning in children’. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 380–90. McGrath, R. G. (1999). ‘Falling forward: real options reasoning and entrepreneurial failure’. Academy of Management Review, 24, 13–30. McGrath, R. G. (2001). ‘Exploratory learning, innovative capacity, and managerial oversight’. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 118–31. McGrath, R. and Cardon, M. (1997). ‘Entrepreneurship and the functionality of failure’. Seventh Annual Global Entrepreneurship Research Conference, Montreal, Canada. McGrath, R., Ferrier, W. and Mendelow, A. (2004). ‘Response: real options as engines of choice and heterogeneity’. Academy of Management Review, 29, 86–101. Meyer, M. W. and Zucker, L. G. (1989). Permanently Failing Organizations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Miles, M. B. and Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Miller, C. C., Cardinal, L. B. and Glick, W. H. (1997). ‘Retrospective reports in organizational research: a reexamination of recent evidence’. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 189–204. Miller, D. (1994). ‘What happens after success: the perils of excellence’. Journal of Management Studies, 31, 325–58. Morrison, E. W. (2002). ‘Newcomers’ relationships: the role of social network ties during socialization’. Academy of Management Journal, 45, 1149–60. © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies Creeping Death and Learning from Failure 545 Ohlson, J. A. (1980). ‘Financial ratios and the probabilistic prediction of bankruptcy’. Journal of Accounting Research, 18, 109–31. O’Reilly, C. A. and Chatman, J. (1986). ‘Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: the effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial behavior’. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 492–9. Pangarkar, N. (2009). ‘Do firms learn from alliance terminations? An empirical examination’. Journal of Management Studies, 46, 982–1004. Petroski, H. (1985). To Engineer Is Human: The Role of Failure in Successful Design. New York: St. Martin’s Press. Pinto, J. K. and Prescott, J. E. (1988). ‘Variations in critical success factors over the stages in the project life-cycle’. Journal of Management, 14, 5–18. Pinto, J. K. and Prescott, J. E. (1990). ‘Planning and tactical factors in the project implementation process’. Journal of Management Studies, 27, 305–27. Popper, K. R. (1959). The Logic of Scientific Discovery. London: Hutchinson. Prahalad, C. K. and Oosterveld, J. P. (1999). ‘Transforming internal governance: the challenge for multinationals’. Sloan Management Review, 40, 31–9. Principe, A. and Tell, F. (2001). ‘Inter-project learning: processes and outcomes of knowledge codification in project-based firms’. Research Policy, 30, 1373–94. Pronin, E. and Ross, L. (2006). ‘Temporal differences in trait self-ascription: when the self is seen as an other’. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 197–209. Reich, W. (1949). Character Analysis. New York: Orgone Inst Press. Ross, J. and Staw, B. M. (1993). ‘Organizational escalation and exit: lessons from the Shoreham nuclearpower-plant’. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 701–32. Royer, I. (2003). ‘Why bad projects are so hard to kill’. Harvard Business Review, 81, 48–56. Schmidt, J. B. and Calantone, R. J. (1998). ‘Are really new product development projects harder to shut down?’. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 15, 111–23. Shepherd, D. A. (2003). ‘Learning from business failure: propositions of grief recovery for the self-employed’. Academy of Management Review, 28, 318–28. Shepherd, D. A. and Cardon, M. S. (2009). ‘Negative emotional reactions to project failure and the self-compassion to learn from the experience’. Journal of Management Studies, 46, 923–49. Shepherd, D. A., Covin, J. G. and Kuratko, D. F. (2009a). ‘Project failure from corporate entrepreneurship: managing the grief process’. Journal of Business Venturing, 24, 588–600. Shepherd, D. A., Wiklund, J. and Haynie, J. M. (2009b). ‘Moving forward: balancing the financial and emotional costs of business failure’. Journal of Business Venturing, 24, 134–48. Shepherd, D. A., Patzelt, H. and Wolfe, M. (2011). ‘Moving forward from project failure: negative emotions, affective commitment, and learning from the experience’. Academy of Management Journal, 54, 1229– 59. Singh, S., Corner, P. and Pavolvich, K. (2007). ‘Coping with entrepreneurial failure’. Journal of Management and Organization, 13, 331–44. Sitkin, S. B. (1992). ‘Learning through failure: the strategy of small losses’. Research in Organizational Behavior, 14, 231–66. Statman, M. and Sepe, J. F. (1989). ‘Project termination announcements and the market value of the firm’. Financial Management, 18, 74–81. Staw, B. M. and Ross, J. (1987). ‘Behavior in escalation situations: antecedents, prototypes, and solutions’. Research in Organizational Behavior, 9, 39–78. Staw, B. M., Barsade, S. G. and Koput, K. W. (1997). ‘Escalation at the credit window: a longitudinal study of bank executives’ recognition and write-off of problem loans’. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 130–42. Suddaby, R. (2006). ‘From the editors: what grounded theory is not’. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 633–42. Tjosvold, D., Yu, Z. and Hui, C. (2004). ‘Team learning from mistakes: the contribution of cooperative goals and problem-solving’. Journal of Management Studies, 41, 1223–45. Ucbasaran, D., Westhead, P., Wright, M. and Flores, M. (2010). ‘The nature of entrepreneurial experience, business failure and comparative optimism’. Journal of Business Venturing, 25, 541–55. Ucbasaran, D., Shepherd, D. A., Lockett, A. and Lyon, S. J. (2013). ‘Life after business failure: the process and consequences of business failure for entrepreneurs’. Journal of Management, 39, 163–202. Van Eerde, W. (2000). ‘Procrastination: self-regulation in initiating aversive goals’. Applied Psychology – An International Review, 49, 372–89. van Witteloostuijn, A. (1998). ‘Bridging behavioral and economic theories of decline: organizational inertia, strategic competition, and chronic failure’. Management Science, 44, 501–19. © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies 546 D. A. Shepherd et al. Wagner, J. A. and Gooding, R. Z. (1997). ‘Equivocal information and attribution: an investigation of patterns of managerial sensemaking’. Strategic Management Journal, 18, 275–86. Weick, K. E. (1990). ‘The vulnerable system: an analysis of the Tenerife Air Disaster’. Journal of Management, 16, 571–93. Weick, K. E. and Sutcliffe, K. M. (2007). Managing the Unexpected: Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Weick, K. E., Sutcliffe, K. M. and Obstfeld, D. (2005). ‘Organizing and the process of sensemaking’. Organizational Science, 16, 409–21. Yin, R. K. (2008). Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications. Zollo, M. and Winter, S. G. (2002). ‘Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities’. Organization Science, 13, 339–51. © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies View publication stats