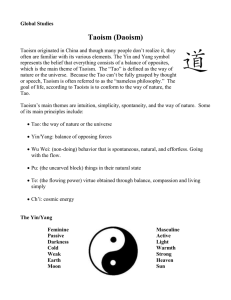

Prompt: Comparing Brahman and Dao Distant Cousins Advaita Vedanta and Daoism are some of the most significant traditions to emerge out of India and China respectively. Daoism provided ancient China with Dao, a new understanding of how to appreciate the natural phenomenon and the cosmos and seek to maintain this natural state. On the other hand, the Advaita Vedanta is a unique branch of the Vedanta tradition which provided a fresh perspective on the nature of Brahman as consciousness. Of interest is the fact that these two traditions came to prominence at very similar Historical periods and within close geographic proximity. Therefore, it warrants us to firstly closely examine what Dao and Brahman exactly are according to these two traditions and then compare and contrast the differences between them. From a metaphysical and epistemological standpoint, I posit that they are very parallel beliefs with a few caveats. In contrast, they are drastically different from an ethical perspective because of the historical context behind the rise of Daoism in China that forced a certain ethical stand to be in stark focus. This relationship between Dao and Brahman whereby they are simultaneously close and yet so far is why I term them distant cousins. Firstly, let us examine the Advaita Vedanta understanding of Brahman as described by Shankara in the Crest Jewel of Discrimination. Shankara lays out a belief system that centres on acquiring an understanding of the true nature of reality being the absolute Atman-Brahman. From a metaphysical standpoint, Brahman is viewed as the absolute, all-encompassing power in the world and that discernment of the truth reveals that the universe itself is Brahman.1 In addition to this, Shankara asserts that notions of individual self, unique to everyone, is simply a false sense of reality that stems from ignorance to the truth of the scriptures. To him there is only Atman, which is pure eternal consciousness that we all possess. Therefore Shankara posits the question, “What can break the misery and bondage of this world?” to which he answers “The knowledge that the Atman is Brahman.”2 This is the absolute and true reality of the world in this tradition that one must gain in order to be liberated from moksha. Shankara states this relationship as almost indescribable but repeatedly uses the phrase, “That art thou” to try and show the interdependence. 3A lack of understanding of this due to ego and ignorance leads to a reliance on our own senses. It causes us to superimpose elements of the Atman-Brahman on to the material and tangible world, this false perception is what Shankara terms as Maya.4 Shankara asserts that for one to be able to gain the true knowledge of Atman, they must have some pre-requisite traits such as intelligence and reason.5 This individual who is qualified to understand Atman, must then seek a teacher who is “a perfect knower of Brahman.”6 The teacher then assists the student to gain the knowledge in the Vedanta scriptures and meditate upon them.7 After these two steps, the last obstacle on one’s path to enlightenment is the individual’s own capability. Ultimately, the ability or lack thereof to renounce pleasure and discriminate between the eternal and non-eternal, determines if you will be enlightened.8 Once 1 Shankara, “Crest Jewel of Discrimination”, 82. Shankara, “Crest Jewel of Discrimination”, 81. 3 Shankara, “Crest Jewel of Discrimination”, 88. 4 Shankara, “Crest Jewel of Discrimination”, 62. 5 Shankara, “Crest Jewel of Discrimination”, 42. 6 Shankara, “Crest Jewel of Discrimination”, 42. 7 Shankara, “Crest Jewel of Discrimination”, 46. 8 Shankara, “Crest Jewel of Discrimination”, 41. 2 one is able to gain the true knowledge of Atman-Brahman they experience a state of pure bliss in constant communion with Atman-Brahman.9 This enlightened being has no regard for the happenings of this world because they understand that it is simply Maya. Shankara declares that “He neither directs his senses towards the external objects nor does he withdraw them. He stands like an onlooker, unconcerned.”10 Their only possible role is as a teacher for others also wishing to gain the true understanding of Atman-Brahman. In summary, Shankara believes that Atman, which is pure consciousness, is the same things as Brahman, the absolute nature of the world and the universe itself. On the other hand, let us consider the view of the Dao as laid out in the Historical Chinese text Daodejing by Lao Tzu/Laozi. The doctrine of Daoism involves acting and living life in a manner that presents minimal disturbance to the natural cosmic patterns and changing society to reflect this. Dao is the central pillar of this tradition and is translated to almost literally mean ‘The Way’, which is seen as enduring path all followers of Daoism must take.11 Dao is seen almost as this inexpressible, transcendent, non-being that pre-existed even the universe but that contains everything.12 Thus, even if it is a non-being it is seen as the mother of heaven and earth, which cannot be named but only be described as the way. It is also described almost like a force of nature in itself, not deliberate in its actions yet responsible for all that happens.13 Here, the earth is seen as a realm for us humans while heaven is seen a pure realm that is not wholly disconnected from the earth. In short, “People follow earth, earth follows 9 Shankara, “Crest Jewel of Discrimination”, 139. Shankara, “Crest Jewel of Discrimination”, 144. 11 Kohn, Livia. Daoism Handbook. Leiden: Brill, 2000, 20. 12 Le Guin, Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching, 25. 13 Le Guin, Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching, 37. 10 heaven, heaven follows the Way, the Way follows what is.”14 A key metaphysical and cosmological term connected to the beginning of the world in Daoism is Ying and Yang. These are seen as being opposite dualities whose “interplay of energy makes harmony.”15 In the beginning of the world, this duality is what causes a split to occur starting from the way, heaven and earth and so on. “The Way bears one. The one bears two. The two bear three. The three bear the ten thousand things” with the ten thousand things being a representation for everything.16 Another key term to understand in Daoism is the concept of De which is taken to be the virtue that one attains when they follow the Dao.17 These two notions of Dao and De intertwine closely, with even the Daodejing being split into two Books, Dao and De. The chapters on De look at values like Integrity, love of life, and trust that one acquires if they accept the way and grow in wisdom in it. Finally, it is important to examine the notion of Wuwei, effortless action, within Daoism. This is importance of this is highlighted as “When you do not-doing, nothing’s out of order.”18 Lao Tzu examines the patterns of the world and its natural order of things (ziran) as a sacred object thus “to do anything to it is to damage it.”19 In order to accomplish this inaction, Lao Tzu prescribes being devoid of want and urges contentment with the state of the world on the way.20 An individual who wants less and follows the way is supposed to be completely is selfless in how they act to restore the natural balance. This is the basis of the 14 Le Guin, Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching, 25. Le Guin, Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching, 42. 16 Le Guin, Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching, 42. 17 Kohn, Daoism Handbook, 21. 18 Le Guin, Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching, 3. 19 Le Guin, Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching, 29. 20 Le Guin, Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching, 40. 15 ethical prescriptions that the Daodejing lays out to followers of the way. Goodness is compared to the innate nature of water as being pleasant and nourishing to everyone irrespective of who they are, thus one is urged to magnanimous in their good deeds.21 The Daodejing especially makes the case for what a good leader is and the traits that they should have in line with this ethical view point of selflessness. Therefore, followers of the way must be altruistic and act through inaction so as to maintain the inherent way of the world. Having understood what Brahman and Dao entail, it is evident that there are both some similarities and clear differences between the two that deserve some attention. I shall seek to compare and contrast between the two across metaphysics, ethics and epistemology. The first clear metaphysical parallel between the two is how both Dao and Brahman are viewed as being the absolute enveloping powers in the world. It is also worth noting that Daoism views the self as just being another iteration of Dao, similar to how the self is viewed as Atman in Brahmanism.22 The caveat with this parallel being that Brahman is viewed as pure consciousness, which is the true nature of the universe itself, while Dao is a non being that gave rise to the world. This caveat exposes other differences like the fact that the realms of heaven and earth are seen as being true due to the ying yang effects on the Dao. On the other hand, in Brahmanism the material world as people perceive it is simply a relative plane of existence arising from Maya, which is fundamentally not true. Therefore, there are some clear metaphysical similarities between the Dao and Brahman with a slight caveat. 21 22 Le Guin, Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching, 8. Le Guin, Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching, 54. From an ethical perspective, there are some very distinct differences between Brahman and Dao. There is not really a comprehensive ethical framework established in Brahmanism with the focus simply being on being able to gain the right knowledge of Atman-Brahman. Shankara does state that karma from one’s actions does apply, however when one gains the true knowledge of Atman-Brahman they are stated to be uncaring as to what occurs elsewhere. This calls into serious question the ethical implications of one enlightened by the AtmanBrahman because they would exhibit extreme passive inaction even in the face of injustice. Under Brahmanism, ethics takes a back seat to answering the question on the nature of reality. Daoism is the complete polar opposite with ethical considerations taking center stage throughout the Daodejing. This can clearly be understood when one looks at the Historical context of the writing of the rise of Daoism in China. It was written at a time when China was undergoing great political turmoil, hence Daoism rose up to try and restore order in China.23 It was also in response to Confucianism, which was the dominant philosophical school of thought at the time. Confucianism promoted humanism above all else and the Daoist believed that this emphasis on humanist values led to desire and greed, which was responsible for society’s ills.24 Therefore, to the Daoists true humanity is not contrived but rather acts in simplicity and in harmony with nature.25 Thus, not only are ethical considerations of the individual considered, there is also a lot of thought put into how a leader should treat his people. This specific ethical advice to leaders ranges from not waging wars, ensuring the populace is unknowing, and not 23 Coutinho, An Introduction to Daoist Philosophies, 75. Coutinho, An Introduction to Daoist Philosophies, 65. 25 Coutinho, An Introduction to Daoist Philosophies, 66. 24 levying unnecessary taxes.26 For example, Lao Tzu states that, “A Taoist wouldn’t advise a ruler to use force of arms for conquest; that tactic backfires” in response to the constant civil wars.27 Therefore, the historical context of the rise of Daoism and Brahmanism provides key insight as to the significant difference in the weight of ethical considerations that these two traditions give. Lastly, we should examine the close relationship between the epistemology of Dao and Brahman. Epistemology in this sense is the “the study of the interrelation of mind and matter in the processes of perception and knowledge.”28 Both of these texts place heavy emphasis on the fact that true understanding of Dao and Brahman transcends all physical senses and intelligence. For both of these traditions, knowledge only forms the initial level of understanding that one can gain about the true understanding of the world. Shankara does assert that for one to gain the true knowledge of the Atman, they must meditate upon the scriptures and find a teacher to help them along the process. To finally achieve enlightenment one must go a step ahead and once they do all the scripture in the world becomes irrelevant to them. Similarly, the Daodejing itself forms a cursory introduction to the nature of Dao that one can use but ultimately, knowledge is not enough. In fact the importance role that intuition plays in the bid to follow the natural way is stressed in the Daodejing, arguing that intellect can actually be counterproductive to the Dao. Lao Tzu laments that “The more experts a country has the more of a mess it is in” instead advising that one should intuitively “Run the country as 26 Le Guin, Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching, 30. Le Guin, Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching, 30. 28 Theodor, Ithamar, and Zhihua Yao. Brahman and Dao: Comparative Studies of Indian and Chinese Philosophy and Religion, 41. 27 expected.”29 Even in trying to bring out the true nature of the Dao, Lao Tzu still describes it as being a “mystery of all mysteries”, something that we cannot fully discern.30 It is also important to note that, ultimately it is the individual that has to come to this realization of the true understanding. Consequently, it is clear that Dao and Brahman are very similar when it comes to the relationship between knowledge and gaining true understanding. In conclusion, it is clear there are some clear metaphysical parallels between Dao and Brahman because of their transcendent nature, however caveats arise due to their exact nature. They are also very similar when it comes to the relationship between how members acquire knowledge and true understanding of the absolute truth of Brahman or Dao. That being said, they differ greatly in terms of their outlook on ethics because of the Historical contexts in which they arose. Therefore, it feels completely justified to term Brahman and Dao as distant cousins. Bibliography Coutinho, Steve. An Introduction to Daoist Philosophies. New York. Columbia University Press, 2014. Kohn, Livia. Daoism Handbook. Leiden: Brill, 2000. Laozi., Ursula K. Le Guin, and Jerome P. Seaton. Lao Tzu : Tao Te Ching : a Book About the Way and the Power of the Way : a New English Version / by Ursula K. Le Guin with the Collaboration of J.P. Seaton. Boston, Mass: Shambhala, 2009. 29 30 Le Guin, Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching, 57. Le Guin, Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching, 1. Shankara, Crest-jewel of Discrimination (Prabhavananda & Isherwood translation), 1947. Theodor, Ithamar, and Zhihua Yao. Brahman and Dao: Comparative Studies of Indian and Chinese Philosophy and Religion. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2015.