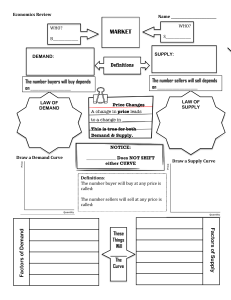

Summary Principles of Economics 1 Chapter 1: Big Ideas Incentives: rewards and penalties that motivates behavior. Big Idea 1: Incentives Matter: Economists don't think everything is self-interested. Economists thinks that people respond in a predictable way to incentives of all kind (fame, power, sex, reputation…). Also benevolence responds to incentives, ex. charities, publicize the name of their donors. Big Idea 2: Good Institutions Align Self-Interest with the Social Interest: Under the right conditions markets align self-interest with social-interest, even if they are at odds. Ex. A u shot prevents you from getting the u but it also reduces the chances that other people will get the u. The Invisible Hand of Adam Smith. But Markets do not always align self interest with social interest, for example a rm that does not pay for the pollution it emits into the air has a too great an incentive to emit pollution. When markets don’t properly align self-interest with social-interest, the government an improve the situation by changing incentives with taxes, subsidies or other regulations. Big Idea 3: Trade-o s are Everywhere: Drug (Medicine) example: Economist worried that approved pharmaceutical could become too safe after the Vioxx incident. A drug being too safe has trade-o s: Researching, developing and testing a new drug cost times and resources. Drug lag and Drug loss: Drug lag: tests takes time, good drugs delayed just like bad drugs. The longer it takes to bring new drugs to the market the more people are harmed who could have bene tted if the new drugs had been approved earlier. You can de because an unsafe drug is approved but you can also die because a safe drug has not yet been approved Drug loss: Greater the costs of testing, fewer drugs will be, higher costs mean a higher hurdle, fewer new drugs, and fewer lives saved. You can die because an unsafe drug is approved, but you can also die because a safe drug is never developed. We face trade o s because of scarcity, there are not enough resources in the world to satisfy all our wants. The Great Economic Problem is how to arrange our scare resources to satisfy as many of our wants. Big Idea 3: Opportunity Cost: The opportunity cost is the value of the opportunities lost. Example: if you are choosing to now attend university. You are paying 10000€ in tuition fees a year. Is that your opportunity cost for attending university? No, it’s not. The main opportunity you lose when you attend university are al the possible things you could have done otherwise. For example, you could have done a job earning you 25,000€ a year instead. This concept is important for two reasons: • If you don’t understand the opportunities you are losing, you won’t recognize the real trade-o s that you face. • The most of the time people do respond to changes in opportunity cost, so if you want to understand their behavior you need to understand opportunity cost. Big Idea 4: Think on the Margin: Thinking on the margin is a requirement when you make a trade-o . Constantly weighing bene ts and costs while making a decision is thinking on the margin. You are thinking in terms of marginal bene ts and marginal costs (a little bit more or a bit less). Big Idea 5: Trade makes people Better O : fi ff ff fi fl ff fl fi ff ff fl ff fi 1 Trade allows us to take advantage of economies of scale, the reduction in costs created when goods are mass-produced. Since not everyone can produce everything, it’s better o if they produce what they are best at and trade for everything else. The theory of comparative advantage says that when people or nations specialize in goods which have allow opportunity cost, they can trade to mutual advantage. Big Idea 6: Wealth and Economic Growth are Important: Wealth brings us ush toilets, antibiotics, higher education, the ability to choose the career we want, etc…, also it brings women’s right and political liberty, at least in most countries. Wealth economies lead to richer and more ful lled, happier lives. Money and happiness are positively correlated in economics. Big Idea 7: Institutions Matters: Some countries have more physical and human capitals than others but still they are not as successful. This is because it’s important that everything is well organized and that institutions are well aligned in the country’s interest. The most important institutions for supporting good incentives are: • Property right • Political stability • Honest government • Dependable legal system • Competitive and open markets Big Idea 8: Economic Booms and Busts cannot be Avoided but can be Moderated: It is impossible to avoid all recessions. Boom and Busts are part of the normal response of an economy to changing economic conditions. However, all of this can be moderated. Most economists believe that if the US Federal Reserve had acted more quickly and appropriated, the great depression would have been shorter and less deep. Big Idea 9: In ation is caused by Increases in the Supply of Money: In ation is an increase in the general level of prices. In ation is one of the most common problems in macroeconomics. When there is too much money circulating in the economy (the government prints too much), the existing currency loses its value which leads to rising prices. Big Idea 10: Central Banking is a Hard Job: The Federal Reserve is often called on to combat recession. This is a tough job since no one can perfectly foresee the future and Fed’s decisions are not always correct. Big Idea 11: Economics is Fun: Lmao funny laugh Key Concepts: Incentives, Scarcity, Great Economic Problem, Opportunity Cost, In ation. ff fl fl fi fl fl fl 2 Chapter 2: The Power of Trade and Comparative advantage Three bene ts of Trades: 1. Trade makes people better o when preferences di er. 2. Trade increases productivity through specialization and the division of knowledge. 3. Trade increases productivity through comparative advantage. Trade and Preferences: Trades creates value by moving goods from people who value them less to people who value them more. People with di erent preferences are eventually better o . Specialization, Productivity and the Division of Knowledge: People will only specialize in the production of a single good when they are con dent that they will be able to trade that good for the many other goods they want and need. Thus, as trade develops, so does specialization and specialization turns out to vastly increase productivity. There is also a creation of new knowledge ad it is shared and explored. Absolute Advantage: A country has an absolute advantage in production if it can produce the same good using fewer inputs that any other country. But to bene t from a trade, a country does not need an absolute advantage. Comparative advantage is best explained using a production possibility frontier. (Mexico and US, computer and t-shirts example). Production Possibility Frontier (PPF): Shows all the combination of goods that a country can produce given its productivity and supply of inputs. Comparative Advantage: The ability of an individual or group to carry out a particular economic activity (such as making a speci c product) more e ciently than another activity. There is a close connection between opportunity cost and the PPF. Even though Mexico is less productive than the US in the diagram (pag. 17), Mexico has a lower cost of producing shirts. Since Mexico has the lowest opportunity cost of producing shirts, we say that Mexico has a comparative advantage in producing shirts. ff ff fi ffi ff ff fi fi fi 3 Production and Consumption in Mexico and the United States with Trade: With no trade, Mexico produces and consumes one computer and six shirts, and the United States produces and consumes 12 Computers and 12 Shirts. With specialization, Mexico produces zero computers and 12 shirts and the US produces 14 computers and 10 shirts. By trading three shirts for one computer, Mexico increases its consumption by one computer and one shirt. Thus, everyone can bene t from trade. From the world’s greatest genius down to the person of below-average ability, no individuals or countries are so productive or so unproductive that they cannot bene t from the inclusion in the worldwide division of labour. Trade unites humanity. Comparative advantage and Wages: Ultimately it’s the productivity of labor that determines the wage rate. Specialization and trade let workers make the most of what they have. According to the example above, workers in the US often fear trade because they think that they cannot compete with lowwage workers in other countries. Meanwhile, workers in the low-wage countries fear trade because they think that they cannot compete with high-productivity countries like the US. The di erence in wages re ect di erences in productivity. Trade and Globalization: Not everyone bene ts from increased trade. In our simple model, workers within a country can easily switch between the shirt and computer sectors. In the real world, workers in the sector with increased demand will see their wages rise while workers in there sector with decreased demand will see falling wages. Takeaway: Specialization creates enormous increases in productivity. Without trade, the knowledge used by an entire economy is approximately equal to the knowledge used by one brain. With specialization and trade, the total sum of knowledge used in an economy increases tremendously and far exceeds that of any one brain. Key Concepts: - Absolute advantage p. 16 - Production Possibility Frontier p. 16 - Comparative Advantage p. 17 fi fi ff fl fi ff 4 Chapter 3: Supply and Demand Demand Curve: A function that shows the quality demanded at di erent prices If the price of oil was $55 per barrel, the quantity demanded would be 5 million barrels of oil per day. If the price was $20 per barrel, what would the quantity demanded be? It would be 25 millions barrels, according to the demand curve. Quantity Demanded: The quantity that buyers are willing and able to buy at a particular price. The demand for oil depends on the value of oil in di erent uses. When the price of oil is high, oil will be used only in its higher-valued uses. As the price of oil falls, oil will also be used in lower-valued uses. (Higher value=airline ights; lower value=manufacturing of rubber duck toys). Two ways to read a demand curve: 1. Horizontal Reading: At a price of $20 per barrel, buyers are willing to buy 25 million barrels of oil per day. ( g. 1) 2. Vertical Reading: The maximum price that demanders are willing to pay to purchase 25 million barrels of oil per day is $20 per barrel. In summary, a demand curve is a function that shows the quantity that demanders are willing and able to pay at di erent prices. The lower the prices, the greater the quantity demanded. This is often called the “law of demand”. Consumer Surplus: The consumer gain from exchange, or the di erence between the maximum price a consumer is willing to pay for a certain quantity and the market price. Total Consumer Surplus: Measured by the area beneath the demand curve and above the price ff fi fl ff ff ff 5 What Shifts the Demand Curve?: 1. An increase in demand shifts the demand curve outward, up and to the right. 2. A decrease in demand shifts the demand curve inward, down and to the left. It’s also important to understand what kind of things will increase or decrease demand. Important Demand Shifters: Income: When people get richer, they buy more stu . When an increase in income increases the demand for a good, we say that it is a normal good. Most goods are normal, for example cars and electronics. An inferior good is a good for which demand decreases when income increases, for example instant ramen. Population: When there are more people, there is more demand. Price of Substitutes: If two goods are substitutes, a decrease in the price of one good leads to a decrease in demand for the other good. Price of Complements: If two goods are complements, a decrease in the price of one good leads to an increase in the demand for the other good, and vice-versa. Expectations: The expectations of a reduction in the future oil supply increases the demand today. Future assumptions can a ect demand. Tastes: Fashion trends keep changing, that can a ect demand. The environmental movement has made people more aware of climate change and how the consumption of oil adds carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. As a result, the demand for hybrid cars has increased, more people are recycling, and considering to install solar panel. There are changes in tastes and preferences, another example is the demand for bandanas in 1970’s, it was very high, but today its almost impossible to see anyone wearing them. The Supply Curve: A function that shows the quantity supplied at di erent prices. Quantity Supplied: The amount of a good that sellers are willing and able to sell at a particular price. The supply curve for oil is a function showing the quantity of oil supplied at di erent prices. If the price of oil was $20 per barrel, the quantity of oil supplied would be 30 million barrels of oil per day. The same way, suppliers would be willing and able to sell 50 million barrels of oil at $55. As with the demand curve, you can read a supply curve in two ways. 1. Horizontal Reading: At a price of $20 per barrel, suppliers are willing to sell 30 million barrels of oil per day. 2. Vertical Reading: To produce 30 million barrels of oil a day, suppliers must be paid at least $20 per barrel. ff ff ff ff ff 6 Producer Surplus: The producer gain from the exchange, or the di erence between the market price and the minimum price at which a product would be willing to sell at a particular quantity. Total Producer Surplus: Measured by the area above the supply curve and below the price. What Shifts the Supply Curve: Technological Innovation and changes in the price of inputs: Improvements in technology can reduce costs and increase supply. Taxes and Subsidies: With a $10 tax, suppliers require a $10 higher price to sell the same quantity. The subsidy is a reverse of Tax Expectations: Suppliers who expect that prices will increase in the future have an incentive to sell less today so that they can store goods for future sales. Entry or Exit of Producers: Trade barriers/agreements a ect supply. Changes in opportunity: You have to take into account opportunity cost as that a ects the supply curve. Producers may choose to change their eld which shifts the supply curve. ff ff fi ff 7 Chapter 4: Equilibrium: How Supply and Demand Determine Prices Price is determined by supply and demand. Equilibrium occurs when the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied. In the diagram below, the quantity demanded quals the quantity supplied only when the price is $30 and the quantity exchanged is 65; hence, $30 is the equilibrium price and 65 is the equilibrium quantity. Surplus: A situation in which the quantity supplied is greater than the quantity demanded. Shortage: A situation in which the quantity demanded is greater than the quantity supplied Equilibrium Price: The price at which the quantity demanded is equal to the quantity supplied. Surplus Drives Prices DOWN and Shortage Drives Prices UP: Surplus DOWN: When there is a surplus, sellers have an incentive to decrease their price and buyers have an incentive to o er lower prices. The prices decreases at $30 the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied and there is no longer an incentive for price to fall. Shortage UP: When there is a shortage, sellers have an incentive to o er higher prices. The price increases until at $30 the quantity supplied equals the quantity demanded and there is no longer an incentive for the price to rise. ff ff 8 Who competes with whom? Sellers want higher prices and buyers want lower prices so the person in the street often thinks that sellers compete against buyers. However, economists understands that sellers compete with sellers and buyers compete with buyer. If the market is competitive don’t blame the seller if you can’t achieve the ideal price, blame the other buyers outbidding you. A free market maximize producer plus consumer surplus (the gains from trade): • The equilibrium quantity is the quantity at which the quantity demanded is equal to the quantity supplied; • There are potential gains from trade so long as buyers are willing to pay more than sellers are willing to accept; • There are unexploited gains from trade at any quantity less than the equilibrium quantity; • If the quantity supplied exceeds the equilibrium quantity, it costs the sellers more to produce a product than it is worth to buyers (additionally, the resources would only be wasted, and it would be better to spend them on production of something people really are willing to pay for); • E ective use of the limited number of resources means to produce neither too little, nor too much of a good. A free market maximizes the gains from trade, when: 1. The supply of goods is bought by the buyers with the highest willingness to pay 2. The supply of goods is sold by the sellers with the lowest costs 3. Between buyers and sellers, there are no unexploited gains from trade and no wasteful trades. Under the right condition, self interest leads to a bene cial order, rather than chaos. In Panel A: Unexploited gains from trade exist when quantity is below the equilibrium quantity. Buyers are willing to pay $57 for the 24th unit and sellers are willing to sell the 24th unit for $15, so not trading the 24th unit leaves $42 in unexploited gains from trade. Only at the equilibrium quantity are there no unexploited gains from trade. In Panel B: Resources are wasted at quantities greater than the equilibrium quantity. Sellers are willing to sell the 95th unit for $50 but buyers are willing to pay only $15 so selling the 95th unit wastes $35 in resources. Only at equilibrium quantity are there no wasted resources. If price drop and the supplied quantity increases (e.g due to technological advances), there will at rst be a surplus (excess supply) - but only temporary. fi fi ff 9 Surplus Supply: Sellers are willing to sell more at the old price than demanders are willing to buy. Competition between sellers pushes the prices down, the prices fall, and the quantity demanded will increase until the new equilibrium price and quantity is met. A decrease in supply will raise the market price and reduce the market quantity, having the opposite e ects to an increase supply Increase/Decrease in Demand: The same logic applies when there is an increase/ decrease in demand: If demand increases, the price and quantity point. A decrease in demand will tend to decrease price and quantity Terminology: Demand Compared with Quantity Demanded and Supply Compared with Quantity Supplied: ff 10 A. Increase in quantity demanded is a movement along a xed demand curve (and is always caused by changes in supply) B. Increase in demand is a shift of the entire demand curve (up and to the right) C. Increase in supply is a shift of the entire supply curve (down and to the right) D. Increase in quantity supplied is a movement along a xed supply curve caused by a shift in the demand curve. Comparing Panel A and C shows that shifts in the supply curve create changes in quantity demanded. Comparing Panel B and D shows that shifts in the demand curve created changes in the quantity supplied. fi fi 11 Chapter 7: The Price System: Signals, Speculations, and Predictions Price: Price is a signal wrapped up in an incentive, because prices convey important information, and they create an incentive to respond to that information in socially useful ways. One market can in uence another, and ultimately, an entire series of markets are t together in a global economy. Prices are the key force integrating markets and motivating entrepreneurs. The primary theme: The price system creates rich connections between markets and enables societies to mobilize vast amount of knowledge toward common ends - yet without a central planner. Markets Link the World: To bring just one product from start to end requires cooperative e orts of millions, as illustrated in the rose-example given in the book. This immense cooperation to bring a product from point/state A to point/state B is voluntary and undirected. Each part of the process is people acting in their own self-interest. Markets Link to One Another: Shifs in supply and demand in one market ripple across the worldwide market, changing distant people and products in unforeseeable ways Entrepreneurs are constantly on the lookout for ways to lower costs, and their cost-cutting measures link markets that at rst seem like they are completely unrelated. For example: the moving of the rose business from the USA to Kenya, due to higher oil prices. It was no longer bene cial to grow roses in American greenhouses, as the increased costs would exceed the costs of production in Kenya combined with the transportation costs. When these things occur, entrepreneurs will look to alternative ways to utilize resources, which can then cause additional chain e ects. Solving the Great Economic Problem: The great economic problem is to arrange our limited resources to satisfy as many of our wants as possible. To economize on scarcity, low-value uses must be substituted by other means, whilst the high-value uses must be maintained (whereas there are few substitutes). • Central planning approaches fail because of problems relating to information and incentives (companies have the incentive to promote allocation to their use, even if it is of “low-value”) (impossible to acquire all this information e ectively) • Ideally, each user of the product would compare the value of their use with the value of alternative uses, and have the incentive to give it up if it is of lesser value; this is what the price system accomplishes. In a free market, the price of product X is equal to the value of product X in its next highestvalue use. The equilibrium price slits the uses of a good into 2: • High-value, satis ed demands • Low-value, unsatis ed demands • The value of the highest-value unsatis ed demand is equal to the market price (just below) (increased availability would incentive the market to satisfy the highest-value unsatis ed demand) ff fi ff fi fi fi fl fi ff fi fi 12 Information issue by collapsing all the information into the price (Hayek) The price system also solves the incentive problem, since it’s in a consumer’s interest to pay attention to prices. When the price of a product increases, consumers have an incentive to look for substitutes. In doing so, consumers free up the product so that it can be used elsewhere in the economy where it is of higher value, e.g. oil; asphalt versus jet fuel. In other words, the markets, guided by prices, works as if an “invisible had” guides the process (Adam Smith). A Price is a Signal Wrapped up in an Incentive: Prices are incentives, signals and predictions: 1. When the price increases, users are incentivized to economize by using less or by looking for substitutes 2. An increase in the price is also a signal to suppliers to invest more in exploration, look for alternatives, increase recycling, etc. Speculation Speculation is the attempt to pro t from future price changes, i.e buying/stocking up on a product for a low price, and selling it when the price is high. • With speculation, preparations are made in case of disruption, resulting in more smoothed prices - Speculations will raise prices today, but lower prices in the future, as the disruption will not imbalance the market to the same extent • It will cause an increase in unsatis ed demands now, however it is compensated by having an increase in satis ed demands in the future (which exceeds the unsatis ed demands in the present) • Speculation is never guaranteed to be correct, which can have devastating e ects for the company/individual speculating. Futures: Standardized contracts to buy or sell speci ed quantities of a commodity of nancial instrument at a speci ed price with delivery set at a speci ed time in the future. Most future contracts are settled in cash (cash settlement). Signal Watching: Speculators can push up the futures price of a product, which created da signal that tells others that people with their own money on the line believe that supply disruptions may soon occur. E.g futures prices for oil, currencies, and many commodities can be found in a newspaper or online, so anyone who wants to forecast events in the Middle East can bene t from reading price signals fi fi fi ff fi fi fi fi fi 13 fi fi When a consumer compares the price of product X to the value of product X for a speci c task Y, he is comparing the opportunity cost. Prediction Markets: A prediction market is a speculative market designed so that prices can be interpreted as probabilities and used to make prediction The best known prediction market is the Iowa Electronics Market. The Iowa market let trader use real money to buy and sell “shares” of political candidates, essentially meaning that the market price for a share that candidate X wins is the speculated prediction of the election. Chapter 11: Costs and Profit Maximization Under Competition To maximize pro t, these questions must be answered: 1. What price to set? 2. What quantity to produce? 3. When to enter and exit the industry? What Price to Set? Usually the prices are set by the market. Pricing is easy; you can’t sell any of your products at a price above the market price and you can sell all your products at the market price (no reason to price it lower than the market price). The market price will be a maximization of your pro ts as it is the equilibrium of supply and demand. If there are plenty of substitutes for your product, the demand for your product is most likely perfectly elastic ( at) at the world price. • A perfectly elastic demand curve for rm output is a reasonable approximation when the product being sold is similar across di erent rms and there are many buyers and sellers, each small relative to the total market ELASTICITY = Price Sensitivity = How Sensitive the Demand is to Price Changes Demand curves are more elastic in the long run • The long run is the time after all exit or entry has occurred • The short run is the period before exit entry can occur There are sometimes many potential sellers, so a perfectly elastic demand curve can be a reasonable assumption even in a market with a few rms, at least in the long run Economists say that an industry is competitive when rms don’t have much in uence over the price of their product; under these following conditions: 1. The product sold is similar across sellers (little di erentiation) 2. There are many buyers and sellers that make up small shares of the total market 3. There are many potential sellers (such as new rms establishing if a monopolist has unfair prices) Firms have a lot of in uence on the price of their product when: They sell a product that there are few or no other sellers of, including potential sellers Maximizing Pro t Sunk Costs: are costs that has already been incurred and that cannot be recovered. E.g $15 dollars for a ticket for a bad lm, they money is gone, so ignore the cost and do the only thing that can be changed, walk out. Fixed Costs: are costs that do not vary with output. E.g paying rent for the land that the rms utilized Variable Costs: are costs that vary with output. E.g costs for electricity, maintenance, storage, transportation, etc. as they will vary depending on output - less output equals less transportation fl fi fi ff fi fi fi ff fi fl fi fl fi fi fi 14 Opportunity Costs: Total costs include explicit money costs and implicit opportunity costs; the costs of foregone alternatives Explicit Costs: ate the costs that require actual monetary spending (a monetary outlay), e.g buying goods for your retail store, rent, electricity, etc. Implicit Costs: are costs that does not require monetary spending, e.g trade-o s of investing your savings into a production versus interest rates from continued saving The economic de nition of pro t di ers from the accounting de nition of pro t because accountants typically don’t take into account all opportunity costs. -Economic pro ts are typically less than account pro ts Economic pro ts is total revenue - total costs including implicit costs [TR - (TC + IC)] Accounting pro ts is total revenue - explicit costs (TR - TC) What quantity to produce? Pro t = π = Total revenue − Total cost (TR - TC Total Revenue (TR) = Price x Quantity Sold (P x Q Total Cost (TC) = Fixed Costs + Variable Costs (FC+VC Total cost is the cost of producing a given quantity of output. Total costs are harder to determine, as they include opportunity costs, not just money costs. Understanding the pro t maximization decision requires us to distinguish among many different costs - not just total costs, but also average costs, marginal costs, xed costs, and a few others. Fixed Costs: are costs that do not vary with output. E.g paying rent for the land that the rms utilized Variable Costs: are costs that vary with output. E.g costs for electricity, maintenance, storage, transportation, etc. as they will vary depending on output - less output equals less transportation Pro t is the di erence between total revenue and total cost. To nd the maximum pro t, one method is to look for the quantity that maximized TR - TC. • Instead of looking at total revenue and total cost, one can also compare the increase in revenue from selling an additional product (marginal revenue), to the increase in cost from selling an additional product (marginal cost) • Producers wants to increase production as long as marginal revenue > marginal cost, which means that the halting point (stop) should be the place where marginal revenue = marginal cost. Marginal Revenue (MR) = Total Revenue / Quantity (TR / Q Marginal Cost (MC): is the change in total cost from producing an additional unit The extra cost related to additional production are marginal costs. It is vital to avoid a situation where marginal costs exceed marginal revenue, as that provides a loss. Marginal costs will increase and become exponentially high at a certain point, as either maximum capacity is reached, the price is pushed down too much by fi fi fi ff fi fi fi ) ) ) ) fi ff fi fi . fi fi fi ff fi fi fi 15 increasing supply, or having an excess surplus that there is no demand for. In the example, the pro t-maximizing quantity is 8, as MC = MR. Additional production would lead to MC exceeding MR. The pro t-maximizing quantity is where MR = MC • If MR = P, the pro t-maximizing quantity is where P = MC. • Pro t-maximization in competitive industries is therefore: P = MC = MR • Even though the additional unit resulting in pro t-maximization does not provide additional pro t, it is “just the right” point between too little and too muc As price changes, so does the pro t-maximizing quantity: If the product price increases signi cantly, the rm will expand production until it is once again maximizing pro t when P = M Pro ts and the Average Cost Curv Even if a rm maximizes pro ts, it can still have low pro ts or losses. The average cost of production is total costs divided by quantity. The average cost of production is the cost per barrel, that is, the total cost of producing barrels dived by Quantity Average Cost (AC) = Total Cost / Quantity (TC / Q) The graph below shows the relation between price, marginal cost and average cos Pro t = Total Revenue - Total Cost (TR - TC) Pro t = [(TR/Q) - (TC/Q)] x TR = P x AC = TC / Pro t = (P - AC) x When marginal cost is below average cost, the average cost curve is falling, and when marginal cost is above average cost, the average cost curve is rising, so AC and MC must meet at the minimum of the AC curve, t . . h fi fi fi fi e C fi fi fi Q fi fi Q fi Q fi Q fi fi fi fi fi fi 16 Always draw the MC curve rising through the minimum point of the AC curve. What is the lowest price per barrel that will give the rm a pro t? (No loss) Assuming that P=MC at all times: 1. When P > AC, the rm is making a pro 2. When P < AC, the rm is making a los When should the rm enter of exit the industry? Entry, exit and shutdown decisions Firms seek pro ts, so in the long run rms will: 1. Enter the industry when P > A 2. Exit the industry when P < A 3. Neither enter or exit when P = AC (zero pro ts) A. Zero/Normal pro ts occur when P = AC. At this price the rm is covering all of its costs, including enough to pay labor and capital/ nance their ordinary opportunity costs. The rm does, however, not make any excess pro ts. Average cost includes wages and payments to capital, so even when the rm earns “zero pro ts”, labor and capital are being paid enough to keep them in the industry. Short-Run Shutdown Decisions: If P < AC, the rm is making a loss so it wants to exit the industry, but exit typically cannot occur immediately. Fixed costs such as rent contracts cannot be terminated immediately. Therefore, the rm wants to keep the operations going until they are no longer committed to the xed costs. In this scenario, by not shutting down, the rm is able to cover all of its variable costs and some of its xed costs, which is better than not producing anything as well as paying xed costs. Total Costs (TC) = Fixed Costs + Variable Costs (FC + VC In the short-run, xed costs have to be paid no matter how much output the rm produces. Thus the rm should shut down immediately only if TR < VC, alternatively P < VC, or dividing both sides by Q as before, the rm should shut down immediately only if: Price < (Variable Costs / Quantity) [VC/Q] = Average Variable Costs (AVC AVC = Variable Costs / Quantity (VC/Q Shut down immediately if: P < VC/Q -> P < AV ) fi fi ) fi fi fi fi fi C fi ) fi fi C fi C fi fi fi fi fi fi t fi fi s fi fi fi fi fi fi fi 17 Entry, exit, and industry supply curve 1. Increasing cost industry is an industry in which industry costs increases with greater output - shown with an upward sloped supply curve. As seen below, when the prices increases, so does the opportunity to pro t-maximize by expanding along the MC curve until P = MC, effectively increasing the industry supply/output as industry costs increase with it. fi s 18 fi fi The AVC curve gets closer and closer to the AC curve as Q increase: As production increases, the MC curve will exponentially increase. At some point, the xed costs will make up less and less of the total costs, as they are more or less static unless they are expanded on, i.e buying more land to expand the production facility. The variable costs will however increase ad production increases (more electricity, labor, etc.), reaching a point where they are higher or equal to the xed costs. 3. Decreasing cost industry is an industry in which industry costs decrease with an increase in output; shown with a downward sloped supply curve A. It becomes cheaper to produce the product in a place where there are already a lot of producers of the same, and environment is laid out for production of this good Key Concepts: long run, p. 197 short run, p. 197 total revenue, p. 197 total cost, p. 197 explicit cost, p. 198 implicit cost, p. 198 economic pro t, p. 198 accounting pro t, p. 198 xed costs, p. 199 variable costs, p. 199 marginal revenue, MR, p. 199 marginal cost, MC, p. 199 average cost, p. 202 zero (normal) pro ts, p. 204 increasing cost industry, p. 206 constant cost industry, p. 206 decreasing cost industry, p. 206 fi fi . fi fi fl fi 19 fi fi fi 2. Constant cost industry is an industry in which industry costs do not change with greater output - shown with a at supply curve. In a constant cost industry, when the industry expands, it does not push up the price of its inputs and thus industry costs do not increase. A. As the industry is so competitive, the rms are forced to price their services at near average cost and earn zero or normal pro ts, as they would lose business otherwise. In a constant cost industry, an increase in demand will raise the prices in the short run as each rm moves up its MC curve. However, the expansion of old rms will quickly push the price back down to average cost. Chapter 12: Competition and the Invisible Hand Invisible Hand property 1: Says that by producing P = MC, the self-interested, pro tseeking behavior of entrepreneurs results in the minimization of the total industry costs of production even though no entrepreneurs intends this result. Every rm in the same industry faces the same prices, thus in a competitive market with N rms, the following is true: P = MC1 = MC2 = … = MCN The way to minimize the total costs of production is to produce just so much on each farm that the marginal costs of production are equalized, MC1 = MC2. In the example provided, the cost-minimizing way to produce 200 bushels is to produce 75 bushels on farm 1 and 125 bushels on farm 2. If one person is the owner, he can “central plan” and allocate productions across the two farms so that the marginal costs are equal, and thus the total costs of production are minimized - however, a “centralized planner” is not necessary due to the invisible hand. • In pursuit of self-interest (pro t), they end up minimizing the total costs of production • The invisible hand property 1 says that even though no actor in a market economy intends to do so, in a free market P=MC1=MC2=…=MCN and, as a result, the total industry costs of production are minimized. Without free trade, the total costs of producing cannot be at a minimum, since the unconnected producers will face di erent prices, and thus have di erent marginal costs. Invisible Hand Property 2: Says that entry and exit decisions not only work to eliminate pro ts, they work to ensure that labor and capital move across industries to optimally balance production so that the greatest use is made of our limited resources. Creative Destruction: That the pro t rate in all competitive industries tends toward the same level is just a tendency. In pursuit of pro t, entrepreneurs are always trying to discover new and better products and processes which is why new pro table and unpro table industries appear constantly. The Elimination Principle: Above-normal pro ts are eliminated by entry and below-normal pro ts are eliminated by exit - a general feature of competitive markets. Perhaps even more importantly, the elimination principle tells us that to earn above-normal pro ts, a rm must innovate. The Invisible Hand works with competitive markets: The Invisible Hand works only in certain circumstances, stated below 1. The prices have to accurately signal costs and bene ts, which isn’t always the case 2. If markets aren’t competitive, the invisible hand doesn’t work either 3. Self-interest doesn’t always align with the social interest. fi fi fi fi ff fi fi fi fi fi ff fi fi fi fi fi 20 Chapter 14: Price Discrimination and Pricing Strategy A rm with market power can use price discrimination to increase pro t. Price Discrimination: Selling the same product at di erent prices to di erent customers The most obvious form of price discrimination is when a rm sets di erent prices in di erent markets. Examples: price can be discriminated by actual physical markets, by each customer’s willingness to pay for the good, or price discrimination based upon the time of buying a service/product in correlation to the use date The demand curve in Arica is much lower and more elastic (price sensitive) the in Europe because, on average, Africans are poorer than Europeans. If GSK wants to set a single world price, it should lower the price in Europe and raise the price in Africa, setting a price somewhere between the pro t-maximizing price in Europe and the pro t-maximizing price in Africa. By doing this, GSK reduced their pro t in Europe, and by raising the price in Africa, they also reduced their pro t in Africa. Thus, pro t at the single price must be less than when GSK sets to di erent prices earning the combined pro t. Principles of Price Discrimination 1. If the demand curves are di erent, it is more pro table to set di erent prices in di erent markets, than a single price that covers all markets. A. Therefore, GSK wants to price discriminate, however, by doing that, they encourage drug smuggling - which hurts GSK’s pro ts 2. To maximize pro ts, the monopolist should set higher prices in markets with more inelastic demand. 3. Arbitrage makes it di cult for a rm to set di erent prices in di erent markets, thereby reducing the pro t from price discrimination. A. Arbitrage: Taking advantage of price di erences for the same good in di erent markets by buying low in one market and selling high in another market To succeed at price discrimination, the monopolist must prevent arbitrage. Arbitrage can e.g be prevented through the usage of electronic tracking, bar codes or physical appearance di erences (red pills vs blue pills) Price Discrimination is common: Businesses care about how much customers are willing to pay, which is the basis they use for their price discrimination. Airlines set prices ff ff ff ff fi fi ff fi ff ff fi fi ff fi fi fi ff ff fi fi fi ff ff ffi fi fi fi ff 21 according to characteristics that are correlated with the willingness to pay. New attractive products will usually always be highly priced to bene t o the most interested customers. Perfect Price Discrimination (PPD): Under perfect price discrimination (PPD), each customer is charged their maximum willingness to pay. A monopolist with PPD results in zero consumer surplus, as every consumer is charged their maximum. Is Price Discrimination Bad? Price discrimination is bad if the total output with price discrimination falls or stays the same, but if the output increases under price discrimination, the total surplus will usually increase. • Price discrimination has additional bene ts in industries with high xed costs: E.g The reason there are more drugs to treat common diseases is because the market is larger; it costs the same to develop a drug for a rare or a common disease, but the revenue are much greater for the drug that treats a common disease. Thus, the larger the market, the more pro table is to develop a drug for that market. Tying: Occurs when to use one good, the consumer must use a second good that is sold (only) by the same rm. Firms can price-discriminate by trying two goods and carefully setting their prices. The printer itself is cheap, so that it meets the consumers with a low willingness to pay those that use printers. Ink cartridges are expensive, which meet the consumers with an high willingness to pay, those that use printers a lot. Bundling: Is requiring that products be bought together in a bundle or package. When individuals purchases are expensive, whilst the bundle is much more coste cient, more customers can be more inclined to spend a little more for additional components; ref. O ce Bundle. fi ff fi fi fi fi ffi ffi 22 Chapter 27: The Wealth of Nations and Economic Growth Economic growth and quality of life. There is a strong correlation between a country’s GDP per capita and infant survival, as it is with many other bene ts that come with economic growth. Just about any standard indicator of societal well-being tends to increase with wealth. Key Facts about the wealth of nations and economic growth 1. Fact 1: GDP per capita varies enormously among nations. 75% of the world’s population (5b) lives in a country with a GDP per capita less than average (most of the world’s population is poor relative to the US). The distribution of GDP per capita is also not balanced within each nation. 2. Fact 2: Everyone used to bee poor. For most of recorded human history, there was no long-run growth in real per capita GDP. 3. Growth rate is the percentage change in a variable over a given period such as a year. When we refer to economic growth, we mean the growth rate of real per capita GDP 4. Fact 3: There are growth miracles and growth disasters. In principle, economic growth can occur everywhere, and it can be exponentially fast; so fast that it can surpass top nations within a much shorter time window. Growth is not automatic, and some countries show few signs that they have started the growth path, whilst others have fallen o the growth path, such as Argentina. The Factors of Production Physical Capital: Is the stock of tools, including machines, structures and equipment more capital means more productivity. Human Capital: Is the productive knowledge and skills that workers acquire through education, training, and experience. It is produced by an investment of time and other resources. Human capital is the knowledge and skills that a person needs to understand and to make productive use of technology an technological knowledge. Technological Knowledge: Is knowledge about how the world works that is used to produce goods and services - e.g. genetics, chemistry, physics. Technological knowledge is fi ff 23 potentially boundless, and it is possible to advance even if human capital is relatively constant. Organization: Human Capital, Physical Capital and Technological Knowledge must be organized to produce valuable goods and services. Factors of production do not develop themselves; they must be produced and organized to be productive. The key to producing and organizing the factors of production are institutions that create appropriate incentives. Institutions: Are the “rules of the game” that shape human interaction and structure economic incentives within a society. Institution of Economic Growth 1. Property rights: Under communal property, e ort is divorced from payment, meaning that there is little incentive to work. Communal property actually incentivizes free riding; consuming resourced without contributing to the resource’s upkeep 2. Honest Government: E.g when property rights exist on paper - but only paper - it has no value. Corruption is like a heavy tax that bleeds resources away from productive entrepreneurs. Corruption can cause a poverty trap as few people want to be entrepreneurs since their hard work can be taken away from them - thus there is no wealth to steal. 3. Political Stability: Who wants to invest in the future when civil war threatens to wash away all plans? Civil war, military dictatorship, and anarchy can destroy the institutions necessary for economic growth. 4. A Dependable Legal System: If there exists no reliable record of true ownership, there processes can take a long time, hindering e.g. the establishment of stores 5. Competitive and open markets: Failure to organize capital e ciently (factors of production) has a huge e ect on the wealth of nations. ffi ff ff 24 Chapter 29: Savings Investment, and the Financial System The bankruptcy of the investment bank Lehman in 2009 shook the nancial system, having assets worth $691 billion - it was an important nancial intermediary that worked to transform savings into investments Savings: Is income that is not spent on the consumption of goods Investments: Is the purchase of new capital, such as tools, machinery, and factories Savings are necessary for capital accumulation, and the more capital an economy can invest, the greater GDP per capita. The supple of Savings Four major factors that determine the supply of savings: 1. Smoothing consumption 2. Impatience 3. Marketing and psychological factos 4. Interest rates 1. Smoothing Consumption: The desire to smooth consumption over time is a reason to save and, also a reason to borrow. Savings are necessary to nance the capital accumulation that generated high standards of living; no savings results in dried up investment, declining economic growth, and the standard of living drops. 2. Impatience: Time preference is the desire to have goods and services sooner rather than later (all else being equal). The more impatient a person, the more likely that person’s savings rate is low. Impatience is re ected in any economic situation where people compare costs and bene ts over time. 3. Marketing and Psychological Factors: Marketing matters, even for savings. Individuals are more likely to save if it is perceived as the natural or default alternative. Simple psychological changes, in combination with marketing and promotion, can change how people save for their retirement. 4. Interest Rates: Higher interest rates usually cal forth more savings (individually and by more people). Interest rate is a market price, and it has the same properties of market prices. There are 3 reasons people borrow: 1. Individuals wants to smooth consumption: Through borrowing, more people will be able to attend i.e university, as well as being able to spread out the sacri ces 2. Borrowing is necessary to nance large investments: Many new businesses cannot get a proper start without borrowing. More generally, businesses borrow to nance large projects fi fi fi fi fi fl fi fi 25 3. The Interest Rate: The quantity of funds that people want to borrow depends on the cost of the loan, or the interest rate. Equilibrium in the market for loanable funds: The market for loanable funds occurs when suppliers of loanable funds (saver) trade with demanders of loanable funds (borrowers). Trading in the market for loanable funds determines the equilibrium interest rate. In equilibrium, the quantity of funds supplied equals the quantity of funds demanded. Shifts in Supply and Demand: Changed in economic conditions will shift the supply or demand curve and change the equilibrium interest rate and quantity of savings. An increase in the supply of savings causes the equilibrium interest rate to fall, and the quantity of savings to increase. Temporary Investment Tax Credit: An investment tax credit grievers rms that invest in plants and equipment a tax break The Role of Intermediaries 1. Banks: Banks receive savings from many individuals, pay them interest, and then load these funds to borrowers, charging them interest. Banks participate in the process of economic growth, because the bank oversees a process by which our savings are turned into productive investments and also pay a role in the payments system. 2. The Bond Market: A bond is a sophisticated IOU that documents who owes you how much and when payment must be made. Instead of borrowing from a bank, a corporation can borrow directly from the public, e.g. a relative. When a member of the public lends money to a corporation, the corporation acknowledges its debt by issuing a bond. The advantage of bond nance is that large sums of money can be raised and invested in long-lived assets, and the money can be paid back over a long period of time. All bonds involve a risk that the borrower will be unable to pay; default risk A. Collateral: Something of value that by agreement becomes the property of the lender if the borrower defaults (like a deposit) B. Crowding Out: The decrease in private consumption and investment that occurs when government borrows more C. T-Bonds: US Treasury bonds 30-year bonds that pay interest every 6 months D. T-Notes: Bonds with maturities ranging from 2 to 10 Yeats that also pay interest every 6 months E. T-Bills: Bonds with maturities of a few days to 26 weeks that pay only at maturity. A bond that pays only at maturity is also called a zero-coupon bond or a discount bond since these bonds sell at a discount to their face value Bond Pricing Key Factors 1. Equally Risky assets must have the same rate of return (arbitrage principle) 2. The Interest rates and bond prices move in opposite directions The Stock Market: A stock or a share is a certi cate of ownership in a corporation. Owners have a claim to the rm’s pro ts, however, the pro t is what is left after everyone else has been paid. Shareholders can directly bene t if the rm pays out its pro t in dividends, or indirectly if the rm reinvests its pro ts in a way that increases the value of the stock. fi fi fi fi fi fi fi fi fi fi fi 26 What Happens when Intermediation Fails? 1. Insecure Property Rights: Some government do not o er secure property rights to savers, meaning that the saved funds are not immune to con scation, freezes, or other restrictions. Individuals will therefore be reluctant to invest in intermediaries like banks. 2. Control on Interest Rates: An interest rate control will cause a misallocation of savings and a loss of potential gains from exchange. Investment, determined by the supply of savings, will fall below what it would be at the market equilibrium 3. Politicized Lending and Government-Owned Banks: Government-owned banks are useful to authoritarian regimes that use the banks to direct capital to political supporters, which means that the allocation is not as e cient as it can be. 4. Bank Failures and Panic: Systematic problems in the banking systems usually lead to large-scale economic crises, due to the ripple e ects. Therefore, bank failures can often be followed by many small business failures. Owners Equity: The value of the asset minus the debt, E = V - D. The ratio of debt to equity is called the leverage ratio (D/E). Insolvent Firm: Has liabilities that exceeds its assets (can occur if the assets fall in value to a lower value than the debt) Securization: The seller of a secured asset gets up-front cash while the buyer gets the right to a stream of future payments. Sometimes mortgage loans are “securitized” or bundled together and sold on the market as nancial assets The Shadow Banking System: In a commercial bank the money comes from depositors, and they typically have some source of legally guaranteed funding. Due to the insurance, depositors are less likely to panic if “trouble arises”. The shadow banking system included investment banks, hedge funds, money market funds, and a variety of other complex nancial entities. They behave like banks, but they are less heavily regulated and monitored, and their short term sources of funds are not government guaranteed. fi ff ffi ff fi fi 27 ff fi Initial Public O ering (IPO): The rst time a corporation sells stock to the public in order to raise capital Chapter 19: Public Goods and the Tragedy of the Commons This chapter starts with a story about how the world could have ended on September 29, 2004. It refers to an asteroid known as the Armageddon which almost collided with earth. In today’s age, we have something known as asteroid defense. Asteroid defense is a public good because even those that don’t pay for it, bene t from it. It’s not like the whole world will decide that it’s better to just get hit by an asteroid because you are a freerider unwilling to pay. Instead, someone else will pay more. There are 4 important terms: 1. Excludable: A good is excludable if people who don’t pay for can be easily prevented from using the good. E.g. Jeans (If you don’t pay, you can’t wear it) 2. Nonexcludable: A good is non excludable if people who don’t pay cannot be easily prevented from using it. E.g. National Defense 3. Rival: If the use of one good by a person leads to a reduction in the ability of another person to use the same good. E.g Hamburger (If a person eats half of it, your ability to eat it decrease to half as well) 4. Nonrival: If one person’s use of the good does not reduce the ability of another person to use the same good. E.g. Public WiFi (All can use it) There are 4 types of goods 1. Public Goods: Goods that are non excludable and nontrivial E.g. Street Lights 2. Private Goods: Goods that are excludable and Rival E.g. Airplane rides 3. Common Resources: Goods that are non excludable but rival. E.g. Public Roads 4. Club Goods: Goods that are excludable but nonrival E.g. Digital Music Free Rider: A free rider is somebody that enjoys the bene ts of a public good without paying a share of the costs. This is very common for goods like street lights, where even if a non-tax payee drives through a lit street, he is bene tting from it. A forced rider: Somebody who pays a share of the costs of a public good but does not enjoy the bene ts. E.g. If you pay tax in Estonia for public defense but live in South Korea. Entrepreneurs are always looking for ways to turn non-excludable, non-rival goods into club goods. An example is of advertisement on radios and television. Even though they are public goods and can be o ered to anyone, money can still be made o of them by private entrepreneurs through advertisement revenue. Tragedy of the Commons: The tendency of any resources that is unowned and hence nonexcludable to be overused and under maintained. Overexploitation and undermaintenance of the common resource How do you solve the tragedy of the commons? In recent years, command and control, and more recently, tradable allowances have been used to solve the tragedy of the commons problem. As well as that, ITQ’s (Individual transferable quotas) - just like pollution allowances are used. ff fi fi fi ff fi 28 Chapter 32: Business Fluctuations: Aggregate Demand and Supply Business Fluctuations (business cycles): are uctuations in the growth rate of real GDP around its long-term trend growth rate. Recession: Recession is a signi cant, widespread decline in real income and employment Recessions are a concern because they increase unemployment dramatically, in a time when all kinds of resources are not fully employed. The model of aggregate demand and aggregate supply (AD/AS) shows how unexpected economic disturbance or “shock” can temporary increase/decrease the economy’s rate of growth. How does an economy respond to these two types of shocks? 1. Real shocks (aggregate supply shocks) 2. Aggregate demand shocks The AD/AS model have 3 curves: • The aggregate demand curve (AD) • The long-run aggregate supply curve (LRAS) • The short-run aggregate supply curve (SRAS) The Aggregate Demand Curve: The aggregate demand curve shows all the combinations of in ation and real growth that are consistent with a speci ed rate of spending growth (M+v). • • • • Spending growth = In ation + Real Growth M + v = P + Yr OR M + v = In ation + Real Growth M is the growth rate of the money supply v is growth in velocity (how quickly money is turning over) P is the growth rate of prices, the in ation rate (π) Yr is the growth rate of real GDP which we simplify and call real growth Shifts in the Aggregate Demand Curve: Increased spending must ow into either a higher in ation rate or a higher growth rate (M or v respectively). In other words, an increase in spending growth can be caused by either an increase in M or v The Long-Run Aggregate Supply Curve (LRAS) The Solow growth rate: is an economy’s potential growth rate, the rate of economic growth that would occur given exible prices and the existing real factors of production capital, labor and ideas. LRAS is a vertical line at the Solow growth rate fi fl fl fi fl fl fl fl fl fl 29 In the RBC framework, business uctuations are simply changes in economic growth in the short run driven by real shocks. Real Shocks: Rapid changes in economic conditions that increase or diminish the productivity of capital and labor, which in turn in uences GDP and employment. Short-Run Aggregate Supply Curve: The SRAS is upward-sloping, meaning that in the short run an increase in aggregate demand will increase both the in ation rate and the growth rate, and a decrease in demand will decrease both the in ation rate and the growth rate. Menu Costs: The costs of changing prices In the long run, unexepectd in ation always turns into expected in ation and the SRAS curve shifts up and to the left. In the long-run, the in ation rate is found where the LRAS curve intersect the AD curve. The SRAS curve is always moving towards the point where the LRAS curve intersect the new AD curve. fl fl fl fl fl fl 30 fl fl Shifts in the long-run aggregate supply curve Putting the AD and LRAS curve together makes it possible to explain how businesses uctuation can be used by real shocks (often called the “real business cycle” (RCB) model). They are called real shocks or productivity shocks because they increase or decrease an economy’s fundamental ability to produce goods and services and thus, they increase or decrease the Solow growth rate. Shocks to the component of aggregate demand • Changes in M (growth rate of money supply) can create AD shocks • Changes in v (velocity) can be broken into changes in C, I, G, or NX • Changes in v can be thought of as increasing or decreasing the spending rate, holding the money supply constant. Why Changes in Velocity of Money Supply (v) tend to be temporary: A decrease in consumer spending reduces AD and the rate of in ation in this period, however, in the longrun, consumer spending will return to its normal rate, and when it does, AD and in ation will return as well Other Shocks 1. Wealth Shocks can also increase or decrease AD 2. Taxes are another important shifter of C and I National Spending Identity: Y = C + I + G + NX fl fl 31 Fiscal Policy: Federal government policy on taxes, spending, and borrowing that is designed to in uence business uctuations There are two general categories whereas scal policy is used to ght a recession 1. The government spends more money 2. The government cuts taxes, giving people more money to spend Fiscal Policy: The Best Case (Increased government spending) During a recession, whereas C falls, and v falls, the short-run e ects will be noticeable. In the longrun, prices and wages will become “unstuck”, fear will pass, and C will return to its normal growth rate so the economy will return to where it was. The government has some control over G, so if C falls, they can increase G to compensate. Increase In G means that the government is spending more money, and thus, commanding more real resources. The money used must come from taxes or increased borrowing, and that will mean reduced aggregate demand from some quarters, thereby making the increase in G less e ective. The Multiplier: In the best-case scenario, the increase in G does not have to be as large as the fall in C in order to restore the economy, because as G increases, so does C. Since the increase in C multiplies the e ect of expansionary scal policy on AD, this e ect is called the multiplier e ect. Limits to Fiscal Policy: There are 4 major limits to scal policy, and 3 of them have to do with the di culty of using scal policy to shift aggregate demand (AD) 1. Crowding out: If government spending crowds out or leads to less private spending, then the increase in AD is reduced or neutralized on net 2. A drop in the bucket: The economy is so large that government can rarely increase spending enough to have a large impact 3. A matter of timing: It can be di cult to time scal policy so that the AD curve shifts at just the right moments A. Recognition lag: the problem must be recognized B. Legislative lag: congress must propose and pass a plan C. Implementation lag: bureaucracies must implement the plan D. E ectiveness lag: the plan takes time to work fi fi ff ff fi fl ffi fi ff fl ff ff ffi 32 ff fi fi Chapter 37: Fiscal Policy E. Evaluation and adjustment lag: did the plan work? Have conditions changed? 4. Real Shocks: Shifting AD does not help much to combat real shocks. Tax Rebate: A given check, and does not increase the incentive to invest or work Ricardian Equivalence: If people save their tax cut instead of spending it, the aggregate demand curve does not shift to the right and there are no systematic macroeconomic e ects, also known as the Ricardian equivalence Automatic Stabilizers: Automatic stabilizers are changes in scal policy that stimulate AD in a recession without the need for explicit action by policymakers Fiscal policy does not work well to combat real shocks: If the recession is not caused by a fall in C, but by a real shock that reduces the productivity of capital and labor, shifting the long-run aggregate supply curve to the left. Fiscal policy (and monetary policy) is most e ective when the relevant shock is to aggregate demand and there are many unemployed resources Fiscal policy is most likely to matter when: 1. The economy needs a short-run boost, even at the expense of the long-run 2. The problem is a de ciency in aggregate demand rather than a real shock 3. Many resources are unemployed fi fi ff ff 33