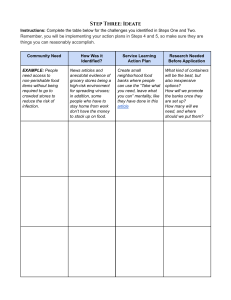

Global Economics | 15th February 2022 GLOBAL ECONOMICS UPDATE What to expect from QT • Quantitative tightening (QT), namely the shrinking of central banks’ balance sheets, is likely to play an active role alongside rising interest rates in the tightening of monetary policy over the coming months. However, central banks will have to play it by ear when it comes to the mix of these policies. If QT sparks a bigger tightening of financial conditions than expected, then interest rates may not have to rise by much. • The unconventional policy measures undertaken during the pandemic have taken central banks’ balance sheets to new highs. (See Chart 1.) Some of the rise has reflected temporary liquidity assistance to ease strains in financial markets, much of which has already reversed as these short-term measures expired. But most reflects longer-lasting policies related to monetary policy objectives. (See Chart 3 in here.) • This balance sheet expansion is only just coming to an end. The Bank of Canada finished buying new assets in October, and the Bank of England did so in December. The RBA is due to stop this month, the US Fed in March and the ECB at the end of this year (though we think this will be brought forward). But already a reversal of this expansion is on the horizon in many of these countries. (See Chart 2 for the US and UK.) While there are good reasons for central banks to keep their balance sheets bigger than they were before the financial crisis (see here), they will want ultimately to reverse a good part of the increase. • The US Fed was the only central bank to undertake QT after the global financial crisis, and it did so extremely slowly. It did not start until October 2017, almost two years after the first interest rate rise, once rates had reached 1% to 1.25%. And caps on the run-down were set very low; initially at only $10bn per month, before rising to $50bn per month (equivalent to only 1.2% of the balance sheet then). • However, there are reasons for the US Fed – and other central banks – to move more quickly now. (See here.) Financial conditions are even looser now, and the US Fed in particular faces an unusually flat yield curve for the start of a tightening cycle. (See here.) Inflation is higher. Central bank balance sheets are much bigger. And in the case of the US, the Fed has a new standing repo facility which should help to avoid a recurrence of the bout of volatility in markets seen during the QT of 2019. • Most central banks want to wait until they have begun to raise interest rates before starting QT. The exception is the Riksbank, where we think that balance sheet reduction will take precedence over rate hikes, given the substantial stock of mortgage-backed covered bonds that the central bank has acquired over the past year. (See here.) There are various reasons for prioritising rate rises over QT. Interest rates are quicker and simpler to control. They have a more reliable relationship with inflation. And central banks seem to view creating headroom to cut rates again more important than creating headroom to expand QE. • But in most cases, the gap between raising rates and starting QT will not be long. As it happens, we don’t think that central banks need to be in a rush to reduce the size of their balance sheets. (See here.) Nonetheless, the Bank of England this month said that it would start its run-off now that Bank Rate has reached 0.5%. The Bank of Canada has said it expects to start QT when its raises interest rates or soon after. And while the US Fed has not yet issued a timetable, it has given a strong indication that the period of time between stopping purchases and shrinking the balance sheet will be short. (Continued overleaf.) Chart 1: Central Banks’ Assets/Liabilities as a % of GDP 140 Japan (LHS) US Fed (RHS) Bank of England (RHS) ECB (RHS) 120 100 Chart 2: Central Banks’ Assets/Liabilities 70 10,000 60 9,000 50 8,000 60 30 40 20 3,000 10 2,000 0 2008 Source: Refinitiv 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020 2022 5,000 1,000 600 4,000 400 200 1,000 0 1,200 800 6,000 40 0 2006 UK (RHS, £bn) 7,000 80 20 US (LHS, $bn) 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 0 Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics Vicky Redwood, Senior Economic Adviser, +44 (0)20 7808 4989, victoria.redwood@capitaleconomics.com Global Economics Update Page 1 Global Economics • The ECB will be more cautious than other DM central banks about shrinking its balance sheet because of the risk of triggering an increase in the spread between core and peripheral bonds. Indeed, it has said that it does not intend to shrink its PEP portfolio until the end of 2024 and that it will maintain its APP portfolio “for an extended period of time past the date when it starts raising the key ECB interest rates”. • Initially, central banks will undertake QT by no longer fully reinvesting the proceeds from maturing assets. This has the benefit of providing a predictable and gradual path for the reduction in the stock and is operationally straightforward. Some central banks have large amounts of assets with a relatively short maturity and so are likely to introduce a cap on the run-down. (See Chart 3.) This includes the Fed, which has bought a large amount of short-term Treasuries and which we expect to issue a cap that quickly rises to $100bn per month before the end of the year. (See here.) The Bank of Canada is likely to introduce a cap too, in part due to the bumpy profile of its maturing assets. (See here.) • If this process goes smoothly, then central banks may decide to accelerate the process by actively selling assets. This is especially the case for the UK and Australia where the average maturity of the assets held is quite long. Indeed, the Bank of England has said that it will consider actively selling assets once Bank Rate reaches 1% (which we expect to happen in August.) • There are worries about the losses that QT might generate for central banks if it sparks a big rise in bond yields. Given the scale of assets that central banks hold, it would not take much of a loss to wipe out their equity. The simple measure of central banks’ equity on their balance sheets equates to only around 1% of the total value of their assets. (See Chart 4.) However, we have pointed out before that losses do not matter for central banks in the same way they do for companies. (See here.) After all, various central banks, including Chile, the Czech Republic, Israel and Mexico, have pursued their policy aims effectively in spite of technical insolvency in recent years. And if needs be, governments could recapitalise central banks. • It is unlikely that QT will have a big direct impact on the real economy given that – as far as we can tell – QE itself did not have a particularly big effect. Although in theory QE could have led to a surge in bank lending and broad money, this never materialised. So there is little risk of a big monetary contraction now. And it seems unlikely that QT will put a big dent in sentiment. • The main impact of QT is therefore likely to be on financial markets, where QE itself probably had at least some impact. It is possible that QT strengthens expectations of future rate rises. Yet rate rises are already widely anticipated; in fact, if markets view QT as a substitute for rate hikes, it could prompt rate expectations to fall. QT’s main impact will probably be to contribute to a rise in the term premium. (See here.) That said, we are not anticipating a “taper tantrum” style spike in bond yields. Even if this did happen, central banks would probably just pause QT or even resume QE. • If QT generates some tightening of financial conditions over and above that which would be achieved by raising policy rates alone, then it probably makes sense to think of QT as substituting for rate rises to at least some degree. Indeed, some Fed officials have talked about more adjustment to the balance sheet allowing a flatter funds-rate path. If central banks succeed in their aim of undertaking QT in a controlled way, then the impact on the path of interest rates will probably be fairly marginal – although there are still good reasons for them to peak at a relatively low level compared to past cycles. (See our forthcoming Global Economics Focus.) But if QT were to generate an unexpectedly big tightening of financial conditions, then interest rates would presumably peak at a significantly lower level than otherwise. Chart 3: % of Central Bank Holdings of Government Bonds By Maturity Date 25 25 2022 2023 20 15 15 10 10 5 5 0 0 UK Canada Sources: Central banks, Capital Economics Global Economics Update 1.4 1.4 1.2 1.2 1.0 1.0 0.8 0.8 0.6 0.6 0.4 0.4 0.2 0.2 2024 20 US Chart 4: Central Banks’ Equity As a % of Assets Australia 0.0 Japan UK US EZ 0.0 Sources: Central banks, Capital Economics Page 2 Global Economics Disclaimer: While every effort has been made to ensure that the data quoted and used for the research behind this document is reliable, there is no guarantee that it is correct, and Capital Economics Limited and its subsidiaries can accept no liability whatsoever in respect of any errors or omissions. This document is a piece of economic research and is not intended to constitute investment advice, nor to solicit dealing in securities or investments. Distribution: Subscribers are free to make copies of our publications for their own use, and for the use of members of the subscribing team at their business location. No other form of copying or distribution of our publications is permitted without our explicit permission. This includes but is not limited to internal distribution to non-subscribing employees or teams. Email sales@capitaleconomics.com Visit www.capitaleconomics.com