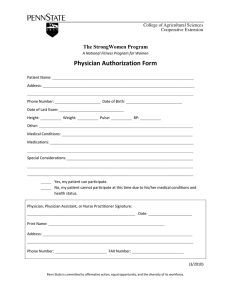

PATiENT EduCATiON ANd COUNSEhNq ELSEVIER Patient Education and Counseling 23 (1994) 131-140 A new model for physician-patient Vaughn communication F. Keller *, J. Gregory Carroll Miles Insiifure for Health Care Communication, 400 Morgan Lane. West Haven, CT 06516, USA Received 21 July 1992; accepted 27 February 1994 Abstract The E4 model for model. Derived from to be a useful tool in Information on how Keywords: physician-patient communication is presented with specific techniques for implementing the an extensive review of the literature on physician-patient communication, the model has proved workshops for and coaching of physicians regardless of specialty, experience or practice setting. to obtain descriptive materials about the workshop and an annotated bibliography is included. Communication; Physician-patient relationships: 1. Introduction The scholarly discussion of physician-patient communication reflects three distinct, although related, perspectives on the topic. Each perspective makes a unique contribution to the discussion (see Fig. 1). The first perspective addresses core beliefs, the philosophy of the physician. It views the physician-patient relationship as a consequence of the physician’s central understanding of the processes of disease and healing. Historically, the dominant construct taught in medical schools has been reductionistic. The healing process has been construed as one in which a physician gathers data about the anatomy, physiology and symptoms of * Corresponding author. 0738-3991/94/$07.00 0 1994 Elsevier Science Ireland SSDI 0738-3991(94)00631-U Adherence; Empathy the patient, constructs a differential diagnosis, determines a treatment plan, and manages the patient in light of that plan. In 1977 Engel challenged this paradigm [ 11. He issued a call for physicians to view disease and healing as open system processes. In this new paradigm the patient becomes a systemic creature with permeable boundaries (mind/body; organism/environment) rather than a complex of isolated symptoms and physical features. In Engel’s approach, mind, body and environment are no longer separated. While Engel’s biopsychosocial model of disease and healing has received significant attention in primary care as an idea, it has received less attention as a guide for physician behavior. Mishler, for example, finds that physicians and patients speak and think about health from very different orientations. Mishler calls these orientations the voice of medicine and the voice of the life world [2]. Ltd. All rights reserved 132 V. F. Keller, J.G. Carroll/ Patient THREE PERSPECTIVES PHILOSOPHY communication BEHAVIOR Psychology of Physician Skills Repertoire of Physician Fig. 1.Three perspectives on physician-patient communication. The second perspective views the physicianpatient relationship as a consequence of the roles that each party enacts towards one another. For instance, Emanuel and Emanuel have written about four role possibilities for the physician to enact: paternalistic, informative, interpretive, and deliberative [3]. Clearly the nature of the relationship and the resulting communication behavior will change depending upon the role position that the physician takes. Similarly, patients may enact different roles. Some investigators have trained patients to become more assertive in interacting with their health care providers [4,5]. Role enactment is a complex process that has ethical consequences since a role both proscribes and prescribes specific behaviors [6]. Consequently, how and what one says in a dialogue is, in part, role determined. The third perspective views the physicianpatient relationship as a consequence of how physician and patient behave towards one another at a verbal level. Two factors have been identified as critical to the physician’s contribution to the difficulties and dialogue: the psychological strengths that the physician brings to this intimate interaction, and the communication skills repertoire of the physician. Psychiatric concepts of transference and counter-transference have been investigated as a method for understanding both the what and the Educ. Couns. 23 (1994) 131-140 why of physician communication behaviors [7]. Small groups called Balint groups are used in some settings to provide physicians with an opportunity to explore the psychological stimuli present in the physician-patient encounter. Similarly, direct educational approaches have been used to increase the repertoire of responses available to physicians as they interact with patients (81. It is our belief that any approach to enhancing the physician-patient relationship must account for all three of these perspectives. We understand this to be a necessary context if one is to avoid the conceptual pitfalls inherent in an atomistic view of physician-patient communication. Beginning, then, with a consideration of illness and healing, we agree with the paradigm that views both illness and healing as complex phenomena that encompass multiple causalities: physical, psychological, familial, communal, cultural, and environmental. Because of these multiple causalities, the amount and kind of information required to understand an illness episode is extensive. Obtaining this information is not always easy as Mishler has demonstrated [2]. The behavioral model which we will present accounts for the complexity of the data gathering and processing tasks inherent in the biopsychosocial paradigm of illness and healing. Although we refer to the physician-patient dialogue, we use it is an abbreviation. We view the patient as a member of an extended intimate system which includes family members, friends and workmates. We view this intimate system as a contributing force to both illness and healing. This view goes far beyond simply including family members in patient visits on occasion: it is a way of thinking about illness and healing [9]. Because of this perspective, we see the physician as always relating to a patient system regardless of who the physician is talking to at a given time. Second, our understanding of the role relationship between physician and patient is one that allows for multiple roles for physician and patient but uses as its center point a relationship of partnership and collaboration. We acknowledge that there are times when it is inappropriate and ineffective to collaborate with patients because of patient desires for autonomy or dependence or 133 V.F. Keller, J.G. Carroll/ Patient Educ. Couns. 23 (1994) 131-140 because of a patient’s ability physical or psychological - to enter into a collaborative relationship [lo]. However, the role relationship we propose uses collaboration and partnership as the ‘default’ mode. In staking out this position we are consciously rejecting both the autocratic and informative models as default stances. We believe it is inappropriate and ineffective for a physician to continuously function as a parent infantalizing his/her patient or as an uninvolved newscaster reporting information to an audience. Both Lipp [l l] and Katz [6] have written eloquently about the dilemmas of the physician in establishing a role relationship that is rooted in ethical concerns for dignity, respect, and healing. However brief the encounter, we view the physician-patient relationship as a process of role enactment in which ethical issues are always present. Finally we see the physician-patient relationship as bounded by the potential of each party to interact with the other. However, the physician, as the professional who assumes responsibility for delivering a service, has a unique responsibility for developing and enhancing the relationship. We believe that the physician’s potential to interact effectively with the patient is constrained by two phenomena. Both phenomena allow for growth strategies. First, we believe it is useful for a physician to understand his or her own psychological responses to a patient, and this can be done most readily when the physician has available to him or her self both the historical antecedents of the physician’s psychological responses, and an awareness of current stresses that are influencing the physician’s interaction with the patient. This understanding does not, in and of itself, provide the physician with a repertoire of effective responses to the varieties of patient situations that present themselves. We believe, therefore, that it is also important for the physician to consciously develop a repertoire of effective communication strategies that are personalized through practice and subject to adaptation through feedback. It is possible, then, to enhance the physicianpatient dialogue from many perspectives which can be labeled philosophical, role taking, and behavioral. Within the behavioral perspective we include concerns for the physician’s psychological responses to the patient as well as the skills repertoire possessed by the physician [12]. We believe there is merit in, and necessity for, all three perspectives. Because of our institute’s organizational mission to provide continuing educational opportunities for practicing physicians in brief workshops, our specific interest has been in the pursuit of a behavioral approach that develops a core repertoire of effective communication strategies. One model for the development of a behavioral repertoire has been proposed by Bird and CohenCole. This model has been used in workshops sponsored by the American Academy on Physician and Patient and serves as the basis for CohenCole’s book on the medical interview [ 131. The model posits that the medical interview has three functions: ‘(a) gathering data to understand the patient; (b) development of rapport and responding to the patient’s emotions; and (c) patient education and behavioral management’ (p. 378 in Ref. [12]). Originally developed as a teaching model, the Bird and Cohen-Cole approach has served us as a point of departure with which to explore our own thinking about the physician-patient dialogue from a behavioral perspective. We believe that the three-function approach can be improved upon and have sought to do so in the model that is offered below. Although the model is behavioral in nature, it is informed by the philosophical and role taking perspectives in which we believe. 2. A model for physician-patient communication The recent history of the healing arts has emphasized the role of the physician as a discoverer and identifier of pathology and as an agent of healing. More simply, the role has been to find a problem and fix it (see Fig. 2). When fixing the problem was beyond the power of medicine, the task was to ease the patient’s suffering and/or minimize any dangerous outcomes if at all possible. As was mentioned above, with the questioning of this ‘find it and fix it’ role definition as overly V.F. Keller, J.G. Carroll/ Patient Educ. Couns. 23 (1994) 131-140 134 Biomedical Tasks Communication Tasks Find It Engage / b Fix It --;’ Fig. 2. Biomedical tasks. narrow, and too focused on pathophysiology, a new paradigm of disease and healing has emerged which accounts for the psychological, sociological, and behavioral forces that are always present. This expanded context has focused attention on the medical interview, and the transactions that occur during the interview, as an area for change. The following model for physician-patient communication presents specific communication strategies to be used in the interview. The model was developed from an extensive review of the literature on physician-patient communication and has been tested in more than 500 workshops conducted for over 8000 practicing physicians from every specialty and region of the USA during the years 1989- 1994. 2.1. Four communication tasks Four communication or relationship tasks must be performed during the medical encounter (see Fig. 3). Each of these tasks requires specific skills. While presented in a sequential manner, these tasks are not performed sequentially. In fact, they recycle during the progress of the encounter. These tasks do not replace or compete with the tasks of Fig. 3. Communication tasks. finding and fixing the problem. Instead, they make it possible to perform the traditional tasks more successfully, while contributing to a more complete approach to the long-term well-being of the patient (see Fig. 4). Since the four elements of the model begin with the letter ‘E,’ we have dubbed it the ‘E4’ component of clinical care. It serves as a complement to the ‘find it and fix it component’ or F2. 3. Engage the patient For a successful encounter to occur, there must be a human engagement. Information and meaning exchange will only take place if the patient and physician are actively engaged in the communication process. The physician can do several things to facilitate this. First, the physician can accept and utilize the knowledge that the thought and articulation process of the physician and patient are essentially different. The physician has a unique vocabulary which has been mastered through years of schooling (some estimates are that a physician learns 13 000 new words during the training process). In V.F. Keller. J.G. Carroll/ Patient Educ. Cows. 23 (1994) Complete Clinical Care Fix It / Fig. 4. Complete clinical care. addition, the physician’s way of thinking and problem solving is also learned. Diagnostically, the decision tree dominates the physician’s thinking. The patient, on the other hand, has an experience of illness which includes lifestyle consequences, fears, and altered roles. The patient does not know the language or the thought process of the physician. However, the patient is the only one who knows and understands the personal story of the illness. This story must, and will, come out as a narrative rather than a scientific outline [2]. The task, for the physician, is to elicit and understand the story. Specific techniques help this happen. The physician can encourage the patient to tell the story in his/her own words [ 141. Specifically inviting the patient to tell the story and supporting the patient while the story is being told will facilitate this process. This does not mean that the decision tree will not be used. However, thinking of the first two to three minutes of the interview as the patient’s time to tell the story in an uninterrupted manner is useful. Unfortunately, observation research indicates that the average 131-140 135 physician interrupts the patient narrative for the first time after only eighteen seconds [15]. Second, the physician can discover all of the complaints. This is especially necessary in primary care settings. Just as most of us do not go off to the cleaners with one garment, most patients do not come to the office with one complaint. Three is more typical. Rarely do patients know how much time the physician has budgeted for a visit. The first complaint presented may not be the most critical one. It is important to engage the patient in such a way that all complaints can be elicited and then prioritized [ 151. Clearly, all complaints will not be addressed in one encounter. However, after the complaints have been elicited the patient can be asked, ‘What were you hoping we would accomplish today?’ Physician and patient can then discuss and agree upon priorities. Without this process, major complaints may be mentioned at the end of the encounter, literally as the patient or physician is about to leave the room. Following are specific strategies for engagement. 3.1. Join the patient Joining takes place during the opening minutes of the encounter. With a new patient, joining takes more time than with a returning patient. The exception to this sequence is an emergency in which the biomedical tasks must dominate. Even in an emergency, introductions are important. Communicate warmth and welcome. Welcome the patient to your setting. It is not unlike being a host or hostess. Introduce yourself and others. Be curious about who the person is as a person rather than their medical problem. Find some common experience, background, or identity on which the two of you can establish some similarity (comfort and trust). Joining goes beyond discussing the weather and parking. It is more than establishing rapport. Listen to the language of the patient and adapt your language system to meet theirs. It is easiest to listen for key words and to use those words. 3.2. Elicit the agenda and the story Invite the patient to tell the story of the illness. The story is told throughout the joining and during the presentation of complaints. Sometimes it is 136 V.F. Keller, J.G. Carroll/ Patient Educ. told after the agenda is set. It must be heard. The first few minutes of the interview is the ‘patient’s time’. This is time to inhale information rather than to organize it. Use open ended questions. ‘I’m curious about.’ ‘Tell me more about.’ Avoid the ‘wh’ questions (when, what, why, where, etc.) during the early stages of the interview. Avoid questions that can be answered with one word. Acknowledge the story. Do not simply say, ‘urn’. Use responses that communicate your interest: ‘That must have been uncomfortable’. Communicate interest physically by leaning towards the patient and looking at the patient. Monitor time. Monitor time at first to make sure you are giving the initial few minutes to the patient to tell his or her story. One physician trained himself by using a silent egg timer. At first he was shocked by his urge to interrupt. 3.3. Set the agenda Do not assume you know why the patient is there. Even when you suspect why the patient has come, you probably do not know the entire story. The task is to establish an agreed upon agenda. Find out all the complaints. Assume there is more than one. Ask for all of them: ‘Anything else on your mind?’ ‘What else has been happening?’ ‘Anything else you are wondering about?’ If the physician does not learn all of the complaints, she or he is not in a position to discuss with the patient what is most critical. It also leads to the ‘door knob’ complaint: ‘By the way doctor . . . .’ Find out the patient’s expectation or goal for the visit. This may differ from the presenting complaint. At times it is as simple as getting a form signed. Frequently, gaining reassurance is the patient’s goal. Agree upon the agenda. It may be necessary to schedule another visit for complaints of less urgency or complaints requiring more time. One physician calls this ‘referring to myself.’ The physician is not passive in establishing the agenda. It is a negotiated process. 4. Empathize with the patient Physicians recognize the medical care they would like for themselves. When they are asked to Couns. 23 (1994) 131-140 describe personal episodes in which they experienced or observed excellent health care, they inevitably mention two things. First, the physician providing care was technically excellent; second, the physician was empathic and present to the patient as a human being. Empathy is not a genetic trait; it can be learned [ 161.It is an active concern for and curiosity about the emotions, values, and experiences of another [ 171. Again, several specific actions are useful. First, the physician can demonstrate awareness that the patient has feelings and values. Noticing and commenting upon what the physician sees and hears from the patient communicates this awareness. Emotions and values are communicated nonverbally as well as verbally. Literally, the physician sees and hears the patient and lets the patient know what is seen and heard. Second, it is important to accept the feelings and values of the patient. Let the patient know that not only are these feelings and values seen and heard, but they are acceptable and, at times, valuable to the physician. Sometimes self-disclosure is an appropriate method for communicating that feelings and values are appropriate topics for discussion. Third, empathy conveys an impression that the physician is ‘present’ and ‘with’ the patient. The opposite of being ‘present’ and ‘with’ is easier to describe. Spiro et al. refer to the physician’s distance as the physician’s communication of equanimity rather than empathy [17]. Or, the physician is distracted by other activities. The physician avoids eye contact, has a blank stare, or allows frequent interruptions: telephone calls, nurse’s questions. Being ‘present’ and ‘with’ requires attention, curiosity, and sincere interest in the world of the patient. The following techniques support the communication of empathy. 4.1. The setting The non-verbal posture and physical setting of the visit facilitate or frustrate an empathic connection. Some practices are simple to initiate. Greet a new patient while they are fully clothed. This need only take seconds. It is not as important for returning patients as it is for new patients. It can be as simple as stopping in the examination room for a few seconds and saying, ‘Hello, I am Dr X. I’ll be with you in a few minutes. The nurse will V.F. Keller. J.G. Carroll/ Patient Educ. Couns. 23 (1994) show you where a gown is and where you can put your clothes’ (if appropriate). Do not write and listen at the same time. Alternate. When listening and questioning, look at the patient. It is more time effective to alternate listening and writing than trying to do them simultaneously. When a physician writes while a patient is speaking, the physician does not hear all that a patient has said and subsequently asks questions that the patient has already answered but the physician did not hear because he or she was busy writing. Sit or stand relative to the patient so that head level is approximately even. (This does not pertain to all parts of the physical examination.) Unequal height conveys dominance. It is a very primitive phenomenon and communicates being ‘above’ the other. It detracts from establishing a physical situation in which empathy is facilitated. Do not permit physical barriers to come between you and your patient. Two that stand out are (a) the chart, (b) the desk. Come from behind the desk so you can sit face to face with the patient. Do not bury your head in the chart. Videotapes of hospital physician-patient visits reveal frequent instances of physician visits with the chart rather than with the patient. 4.2. Create a setting that is psychologically safe Several verbal behaviors contribute to establishing an empathic connection. Awareness of psychological safety is important. Safety exists when we feel welcome, valued, and accepted. Invite a patient to tell you what she/he is feeling or thinking. Be curious about the total experience of the patient as a person who has feelings, values and thoughts. Acknowledge feelings, values and thoughts. Do not evaluate them. ‘I understand that you are scared at the thought of surgery. Lets talk more about it’; not, ‘There’s no reason to be scared’. Notice facial expressions. While facial expressions communicate feelings, you cannot always be sure what feelings are being communicated. Noticing and commenting, however, often gives the patient permission to report the feelings. ‘I see you frown when I mention exercise.’ Use self-disclosure when appropriate. Do not tell the patient your life story. Do share something 131-140 of your life when you believe it will facilitate patient’s well-being. 13-l the 5. Educate the patient Education is a complicated process. A patient will frequently have questions which the patient will not ask or which will occur to the patient only after he or she has left the offtce. Patients have different desires for information. This raises a perplexing dilemma because of the need for informed consent. One position is to assume that most patients want answers to questions about (a) diagnosis, (b) etiology, (c) treatment, (d) prognosis, and (e) functional consequences (impact on lifestyle). The education task is to answer these questions during the course of the visit. There are also questions that certain specialties can expect. For example, geriatricians, obstetricians and pediatricians are consistently asked questions that have a sub-text of, ‘Am I doing the right thing?’ The role of ‘care giver’ to a patient (e.g. a child or parent) brings about a unique anxiety and consequently a different kind of questioning. Patients do not come into the medical encounter as blank slates. Typically they have already talked to someone about what is taking place with them. They may have read something about what they believe their condition to be. Education is not simply giving information. It requires understanding the cognitive, emotional, and value perspectives of the patient. It includes the struggles of the patient to respond to the illness and the health care system. To accomplish this, the physician must discover what the patient knows and how the patient is thinking and feeling about whatever knowledge he or she possesses. The only way to accomplish this is to ask. Thus, patients both want information and have information. Patients may have an incomplete or different map of reality, but they have some map. The physician’s educational task is to explore the map and present the physician’s view of the situation. However, it is the patient’s map that is central and will impact patient behavior, not the physician’s map. The patient may have functional questions that seem trivial to the physician. For 138 V.F. Keller, J.G. Carroll/ Patient Educ. Couns. 23 (1994) example, ‘Do I have to stop working on the night shift?’ The question, though, may reflect a difficult reality for the patient: ‘I get an important pay differential by working on the night shift, but I’ve been doing it for live years now and would like to have a reason my family would accept for changing shifts and making less money’. The following outline can be useful. 5.1. Assess the patients understanding Under customary circumstances, patients will forget 50% of what the physician says the minute they walk out the door. It is important to provide information that fills in gaps and is important to the patient’s health care questions. Find out what the patient knows. Find out how the patient understands the situation and what is to take place. There are only two ways of discovering the patient’s map: listening carefully to the talk of the patient, and asking specific questions. Ask for questions and things they wonder about. Not all patients will ask questions or tell you what they wonder about (anxieties) without being prompted. The statement, ‘Is there anything else that you have been thinking or wondering about’, is more open ended than, ‘Any questions?’ 5.2. Assume questions Patients have questions. They do not always ask them. You can assume they are present. We believe the following eight questions are present in most situations. Consequently, it is useful to develop a protocol for answering them with the same regularity that one asks standard diagnostic questions. Answer questions about their situation. Assume they want to know: (1) (2) (3) What has happened to me? Why has it happened to me? What is going to happen to me, in the shortterm, in the long-term? Answer questions about your actions. Assume they want to know: (1) What are you doing to me (examination, tests)? (2) (3) (4) (5) 131-140 Why are you doing this rather than something else (diagnostic or treatment options)? Will it hurt me or harm me, for how long, and how much (diagnostic and treatment)? When and how will you know what these tests mean? When and how will I know what these tests mean? 5.3. Assure understanding Providing information (teaching) is not educating. Education does not take place until the patient is able to utilize the information in an effective manner. Assuring understanding is an active process. Ask if the patient wants answers to additional questions. Give permission to ask. There are not always answers. It is useful, therefore, to engage around the issue of answers: ‘Are there other answers that you need’, ‘What information would be useful to you at this time?’ Sometimes this will surface the patient’s frustration at the lack of answers or strong reactions to the information he or she did receive. Ask what or how they understand. Discover whether or not the patient understands everything you believe it is important for him/her to understand. Do not ask if they understand. A simple way of doing this is to acknowledge your own fallibility: ‘I know that I forget to mention things at times. So, would you tell me what your understanding is at this point so I am sure we are on the same wavelength and I haven’t forgotten anything.’ 6. Enlistment Enlistment involves two processes, decision making and encouraging adherence, that have the same goal: increasing a patient’s responsibility and competence to care for his or her own health. 6.1. Decision making The first process is that of decision making. A change in the role relationship between physician and patient has developed over the years. The language used by medical settings reflects both the old and new understanding of the role relationship. V.F. Keller, J.G. Carroll/ Patient Fduc. Couns. 23 (1994) For example, ‘doctor’s orders’ and ‘patient management’ reflect role definitions that assigned all power to the physician. By contrast, ‘informed consent’ and ‘advanced directives’ reflect the power of the patient to self-determination, to make decisions about his/her health care. It is insuflicient to believe that patients should become involved in making decisions about their health care. Just as physicians struggle with the new role alignments, so do patients. Some patients will say, ‘I’ll do whatever you tell me to’, or, ‘I’ll do what you think is best’. Consequently, the physician frequently has to take an active role in enlisting the patient in the decision making process [6]. This might include (a) asking the patient about his/her own thoughts about diagnosis and treatment, and (b) clarifying that the physician wants the patient and the physician to think through and reach agreement about critical issues as a collaborative process. Most patients make a self-diagnosis. It is human nature to do so. If your diagnosis and the patient’s differ, the patient will act based upon his or her own diagnosis. Consequently, it is imperative that and discuss the patient’s You understand diagnosis. Ask for the self-diagnosis! One researcher suggests the formulation: ‘I’ve arrived at one explanation of what the difficulty is [provide your explanation]. How does that lit in with what you have been thinking?’ [18]. Listen to, but do not evaluate, the input of others. Be careful not to evaluate the diagnostic suggestions that have been made to the patient by others: spouses, friends, relatives, magazines, or other physicians. Discovering a different opinion is common. Since you cannot determine the veracity of the patient’s report of conversations with others, and you do not know the nature of their relationship to the third party, it is best to maintain a completely neutral position. By contrast, a cardiologist recently told his patient who had asked questions about the Dean Ornish cardiac care program, ‘Only a psychotic would follow that diet’. Strive for agreement. Patients frequently have preferences for treatment. This will influence how they think about diagnosis. They may favor a diagnosis because they favor the treatment associated 131-140 139 with that diagnosis. Consequently the physician must be sensitive to the manner in which the patient brings diagnosis and treatment together. Agreement about a diagnosis improves the likelihood that the treatment will be adhered to. Time spent in discussion bringing about agreement regarding diagnosis is time well-spent. 6.2. Adherence The second enlistment process involves adherence to an agreed upon regimen. The research on adherence, the term currently used to replace ‘compliance’, indicates that roughly fifty percent of the time patients do not adhere to their physician’s recommendations [19]. It is important to note that physicians are not good at predicting who will and will not adhere to a therapeutic regimen. It is also important to note that the patient characteristics that physicians believe influence adherence, do not: sex, socio-economic status, age, etc. It is important for the physician to take an active role in enlisting the patient in the healing process. Research has shown that six specific actions will increase the likelihood of adherence. (1) Keep the regimen simple. The fewer the required behaviors, the more likely it is that the regimen will be adhered to. Complicated regimens can often be better implemented if they are broken down into sequential steps. (2) Write out the regimen for the patient. Much of what a physician says is forgotten the moment the patient leaves the encounter. If pre-printed forms are used, underlining and personalizing the form in any way possible will help. (3) Motivate the patient and give specifics about benefits and timetable. Too frequently patients are not sure why they are doing what they have been asked to do and do not know when they will experience benefits. (4) Prepare the patient for side-effects and for optional courses of action. This is more than a matter of informed consent. Unanticipated sideeffects are much more likely to interfere with a patient’s adherence than those that are anticipated. (5) Discuss with the patient any obstacles to moving forward with the regimen. What will keep 140 V.F. Keller, J.G. Carroll/ Patient Educ. Couns. 23 (1994) the patient from following through? Develop strategies for overcoming these barriers. (6) Get feedback from the patient. It is important for the physician to be assured that the patient understands the regimen. To accomplish this, physicians can ask the patient to state what the patient understands he or she will do. It is also important to ask about adherence to the regimen during subsequent visits. In addition, it is important to discuss how the patient feels about following the regimen. Emotionally, are they committed or reluctant? Enlistment is an active process in which the physician deliberately sets out to establish a health partnership. It begins, however, with the concept that the patient has already thought about what is taking place. Finally, then, be sure that you understand what the patient believes is taking place and how the situation is affecting his/her life. 8. References 1 4 5 6 9 IO 7. Summary II We have identified three perspectives that influence the physician-patient relationship and have taken the position that all three are valid and must be addressed in understanding what takes place between physician and patient: the philosophy of disease and healing held by the physician, the role that the physician assumes and its ethical consestrategies quences, and the communication employed by the physician. The E4 model above describes communication presented strategies that are informed by assumptions about these three perspectives and have proven to be effective through research and clinical experience. The model has been presented to thousands of physicians in a half-day interactive workshop on physician-patient communication for physicians of all specialties and practice settings throughout the USA. Evaluations of the workshops, postworkshop focus groups and follow-up surveys of these physicians months after the completion of workshops show that the model is judged to be useful by the physician participants. Currently, more than two hundred workshops are conducted throughout the United States each year’. 131-140 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 I9 Engel CL: The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977; 196: 126-136. Mishler EC: The Discourse of Medicine. Norwood, NJ: Abler Publishing Corporation, 1984. Emanuel E, Emanuel L: Four models of the physician-patient relationship. J Am Med Assoc 1992; 267( 16): 222 I-2226. Greenfield S, Kaplan S, Ware J: Expanding patient involvement in care. Ann Intern Med 1985; 102: 520-528. Roter D: Patient participation in the patient-provider interaction: the effects of question asking on the quality of interaction, satisfaction, and compliance. Health Educ Monogr 1977; 5: 281-315. Katz J: The Silent World of Doctor and Patient, New York: The Free Press. 1984. Balint M: The Doctor, His Patient, and the Illness. New York: International Universities Press, 1972. Maiman L, Becker M, Liptak G, Nazarian L. Rounds K: Improving pediatricians’ compliance-enhancing practices. Am J Dis Child 1988; 142: 773-779. McDaniel S, Campbell T, Seaburn D: Family-oriented primary care: a manual for medical providers. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1990. Steele D, Blackwell B, Gutmann M, Jackson T: The activated patient: dogma, dream, or desideratum. Patient Educ Couns 1987; IO: 3-23. Lipp MR: Respectful Treatment: A Practical Handbook of Patient Care (2nd edn.). New York: Elsevier, 1986. Epstein R, Campbell T, Cohen-Cole S, McWhinney 1. Smilkstein G: Perspectives on patient-doctor communication. J Fam Pratt 1993; 37(4): 377-388. Cohen-Cole S: The Medical Interview: The Threefunction Approach. St Louis: Mosby Year Book. 1991. Rowland-Morin P, Carroll J: Verbal communication skills and patient satisfaction: a study of doctor-patient interviews. Eva] Health Prof 1990; 13: 168-185. Beckman H, Frankel R: The effect of physician behavior on the collection of data. Ann Intern Med 1984; 101: 692-696. Platt F, Keller V: Empathic action: a teachable skill. J Gen Intern Med (in press). Spiro H, Curnen M, Peschel E. St. James D. eds. Empathy and the Practice of Medicine. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993. Becker M: Improving Adherence [audiotape]. West Haven CT: Miles Institute For Health Care Communication, 1991. Meichenbaum D, Turk D: Facilitating Treatment Adherence: A Practitioner’s Guidebook. New York: Plenum Press, 1987. ‘Information about the physician-patient communication workshop and an annotated bibliography of the literature on physician-patient communication are available at no cost from the Miles Institute for Health Care Communication, 400 Morgan Lane, West Haven, CT 06516, USA; Tel. +I (800) 800-5907.