Veterinary Parasitology Assignment: Filaroidea, Parafilaria, Onchocerca

advertisement

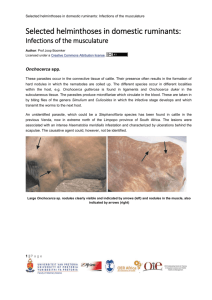

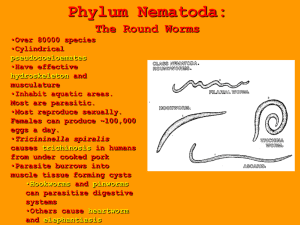

DILLA UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT OF ANIMAL HEALTH ASSIGNMENT OF VETERINARY PARASITOLOGY FOR VET.SC WEEKEND 3RD YEAR STUDENTS SECTION 1 GROUP 1 NAME ID 1.ABAYINEH ESHETU………………………………………….. 002/19 2.ABEL BELAYINEH……………………………..……………… 007/19 3.AYELE WAKO………………………………..………………..027/19 4.EBISA BELAY……………………………...…………………..042/19 5.EJIGAYEHU SHIBIRU………………………..………………...043/19 6.ELIAS IBRAHIM…………………………...…………………..044/19 7.FEYISA WAKAYO………………………………..……………049/19 DATE OF SUBMISSION 6/9/2014 E.C SUPER FAMILY FILAROIDEA Genus Parafilaria and Genus Onchocerca The Filarioidea are a superfamily of highly specialised parasitic nematodes.Species within this superfamily are known as filarial worms or filariae (singular filaria). Infections with parasitic filarial worms cause disease conditions generically known as filariasis. Drugs against these worms are known as filaricides. In and about endemic regions filarial diseases have been public health concerns for as long as recorded history. Archaeological evidence for elephantiasis for example extends back some 3000 years, by which time apparently it already was no novelty. Currently perhaps some hundreds of millions of people worldwide, mainly in tropical regions, are infected with pathogenic species of filariae. Where the diseases are endemic many times more are exposed routinely to infection. Some victims harbour more than one medically significant infection simultaneously and this can complicate diagnosis and treatment. Humankind is the definitive host of at least eight species of filariae in various families. Six are particularly significant in medical terms. The ones that mainly occupy lymph vessels and cause conditions such as adenolymphangitis, elephantiasis, and filarial fever are: -Brugia malayi -Brugia timori -Wuchereria bancrofti Three other Veterinary important parasitic species are: -Loa loa causes Loa loa filariasis also known as Calabar swelling -Mansonella streptocerca, which causes streptocerciasis, an itchy condition that creates depigmented skin lesions sometimes mistaken for the first signs of leprosy. -Onchocerca volvulus causes cutaneous onchocerciasis and river blindness The other two are less seriously pathogenic but commonly parasitise humans. Mansonella ozzardi and Mansonella perstans Some Dirofilaria species usually parasitize animals such as dogs, but occasionally infect humans as well. They are not well adapted to humans as hosts and seldom develop properly though they may cause various confusing symptoms. Life cycle of Filarioidea The mature worms live in the body fluids and cavities of the definitive hosts, or predominantly in particular tissues. Details vary according to species. Some of the worst pathogens invade lymphatic vessels and may be numerous enough to clog them. Some species invade deep connective tissues; some infest subcutaneous connective tissue, causing unbearable itching. Some invade the lungs or serous cavities such as the pleural cavity, or pericardial cavity. Wherever established, they may survive for years, the fertilized females continuously producing motile embryos called microfilariae rather than eggs. A microfilaria cannot reproduce in the definitive host and cannot infect another definitive host directly, but must make its way through the host's body to where an intermediate host that acts as a vector can swallow it while itself acting as an ectoparasite to the definitive host. It must succeed in invading its vector organism fairly soon, because, unlike adult filarial worms, microfilariae only survive for a few months to a year or two depending on the species and they develop no further unless they are ingested by a suitable blood-feeding female insect. In the intermediate host the microfilaria can develop further till the vector conveys it to another definitive host. In the new definitive host the microfilaria complete the final stage of development into sexual maturity; the process takes a few months to a year or more depending on species. The mature filaria then must mate before a female can produce the next generation of microfilariae, so that invasion by a single worm cannot produce an infection. Accordingly, it takes years of exposure to infections before a serious disease condition can develop in the human host. Once a new generation of microfilariae is released in the primary host, those in turn must seek out host tissue suited to the nature of the vector species. For example, if the vector is a skinpiercing fly such as a mosquito the microfilaria must enter the peripheral blood circulation, whereas species borne by skin-rasping flies such as Simuliidae and skin-cutting flies such as Tabanidae tend to establish in hypodermal tissues. For obscure reasons, some such species actually undergo daily migrations to bodily regions favoured by the vector ectoparasites.Outside those periods they take refuge in blood circulation of the lungs. GENUS-PARAFILARIA parasitic roundworms of CATTLE & HORSES. Parafilaria is a genus of filarial parasitic roundworms that is found mainly in the skin of domestic an wild animals worldwide. The most relevant species for domestic animals are: Parafilaria bovicola- that infects mainly cattle, buffaloes and other bovines. It is found worldwide but is more abundant in Africa, Asia and certain European countries (e.g. Russia, Scandinavia, Mediterranean). Parafilaria multipapillosa- is a related species that affects horses, donkeys and mules and is particularly abundant in Eastern Europe. Incidence varies considerably by region and season and is highly dependent on the abundance of the vector flies. These worms do not affect sheep, pigs, poultry, dogs or cats. The disease caused by Parafilaria worms is called parafilariasis, also called summer bleeding disease, verminous nodules, verminous haemorrhagic dermatitis, etc. Are cattle or horses infected with Parafilaria worms contagious for humans? NO: The reason is that these worms are not human parasites. -Predilection site of adult Parafilaria worms is the skin. -Anatomy of Parafilaria Adult Parafilaria are slender worms with a whitish color and up to 6 cm long, whereby females are longer than males. As in other roundworms, the body of these worms is covered with a cuticle, which is flexible but rather tough. The worms have a tubular digestive system with two openings. They also have a nervous system but no excretory organs and no circulatory system, i.e. neither a heart nor blood vessels. Males have a copulatory bursa with two spicules for attaching to the female during copulation. The eggs measure ~30x45 micrometers, have a thin shell and contain a fully developed larva (microfilaria). -Life cycle of Parafilaria Parafilaria worms have indirect life cycles that are not yet completely elucidated. Main intermediate hosts of Parafilaria bovicola are fly species of the genus Musca (e.g. Musca domestica). These flies become infected with microfilariae when they feed on the wounds that cause the worms in the skin of infected hosts. Microfilariae develop to infective larvae inside the flies in a few weeks. Such flies re-infect their hosts while feeding, often on eye tears or other exudates from skin wounds. These larvae penetrate into the skin up to the dermis and migrate further to other locations of the body surface (neck, shoulders, rump, loins, etc.), where they complete development to adults and cause the appearance of nodules. To lay eggs female worms make a hole in the nodule, which results in so-called summer bleeding. The prepatent period (i.e. time between infection and first eggs shed) is 7 to 10 months. Harm caused by Parafilaria, symptoms and diagnosis -Parafilaria infections are not highly pathogenic for cattle or horses. Nevertheless, the worms in the skin can cause hemorrhagic dermatitis ("summer bleeding") with subcutaneous edema.Secondary infections with bacteria can also occur. -Main economic loss results from trimming or even full carcass rejection and/or degradation of hides after slaughter. In working horses, the sores may interfere with the harness. -Diagnosis is based on the characteristic nodules and is confirmed by detection of larvated eggs or microfilariae in exudate samples observed under the microscope. Serodiagnosis (ELISA) is available in some countries. -Prevention and control of Parafilaria -reduce cattle infection. -insecticides. -Sanitation of cattle facilities (e.g. manure removal) can contribute to reducig the fly population. -macrocyclic lactones (e.g.ivermectin) are effective against adult worms, but may not completely control migrating larvae. *This means that after treatment new nodules may appear due to surviving larvae. There are also reports on efficacy of nitroxinil against these worms. GENUS-ONCHOCERCA ONCHOCERCA spp, parasitic roundworms of CATTLE, HORSES & DOGS. Onchocerciasis Onchocerca is a genus of parasitic, thread-like roundworms that belong to the group of Filarioidea, also called filariae. This genus is found mainly in tropical and subtropical regions of the world, including parts of Europe and the USA. Some species with veterinary importance are: Onchocerca armillata nodules on the wall of the aorta. Onchocerca dukei, Onchocerca ochengi and Onchocerca armillata in cattle in Africa. Onchocerca gutturosa in cattle in Australia, North Africa and Europe. Onchocerca gibsoni in cattle in Australia, Asia, Southern Africa and North America. Onchocerca lupi in dogs, worldwide Onchocerca cervicalis in horses worldwide Onchocerca reticulata in horses worldwide Onchocerca raillieti in horses in Africa Incidence varies strongly regionally and seasonally, and depends on the abundance and activity of the intermediate hosts. Dogs were infected with Onchocerca lupi, although most of them were asymptomatic. Onchocerca lupi affects occasionally dogs in North America and Europe, mainly in rural regions, and very occasionally humans as well. Onchocerca volvulus is a human parasite of this genus, the causative agent of river blindness in numerous tropical countries. The disease caused by Onchocerca worms is called onchocerciasis. Are cattle, dogs or horses infected with Onchocerca contagious for humans? Usually No. The main reason is that these worms do not lay eggs or larvae that contaminate their environment or output (droppings, urine, exudates, etc.) and the infective larvae need to spend some time inside an intermediate host (see life cycle below) to become infective for other mammals. Additionally most Onchocerca species that are parasitic for livestock or dogs are not human parasites. Predilection sites of adult Onchocerca depend on each species: Onchocerca dukei subcutaneous, muscular and perimuscular tissues of cattle. Onchocerca ochengi causes nodules in the flanks, udders and scrotum of cattle. Onchocerca armillata in the tunica media (middle layer) of the aorta of cattle. Onchocerca gutturosa in the nuchal ligament and in the connective tissue around the spleen and the rumen of cattle. Onchocerca gibsoni causes subcutaneous nodules in the chest and the hind legs of cattle. Onchocerca lupi in the sclerotic coat of the eyes of dogs. Onchocerca cervicalis in the ligamentum nuchae of horses. Onchocerca reticulata in the connective tissue of the flexor and suspensory ligaments of the fetlock, mainly in the forelimbs of horses. Onchocerca raillieti in the cervical ligament (adults), cysts in the penis and in the connective tissue around the muscles of horses. However, there can be regional differences and the predilection sites depend also on the behavior of the intermediate hosts (see life cycle below). Microfilariae can be found transiently in the blood. Anatomy of Onchocerca Adult Onchocerca worms can be up to 50 cm long, depending on the species, but rather thin. Males are always significantly smaller than females. As other roundworms, the body of Onchocerca worms is covered with a cuticle, which is flexible but rather tough. In this genus the cuticle is transversally striated forming structures like rings. The worms have a tubular digestive system with two openings. They also have a nervous system but no excretory organs and no circulatory system, i.e. neither a heart nor blood vessels. Males have unequal spicules for attaching to the female during copulation.Adult females are viviparous, i.e. they do not lay eggs but already hatched larvae (microfilariae) that are not longer than 0.5 mm. The time between infection and release of infective larvae (prepatent period) is quite long. Depending on the species it may take up to one year. Life cycle and biology of Onchocerca Onchocerca worms have an indirect life cycle with cattle, dogs and other mammals as final hosts and several bloodsucking insects as intermediate hosts, which are species specific. Midges of the genus Culicoides are intermediate hosts of Onchocerca gibsoni, and black flies of the genus Simulium are intermediate hosts of Onchocerca gutturosa and Onchocerca dukei. Adult female worms in final hosts release larvae that reach the blood stream. The bloodsucking insect gets the microfilariae with its blood meal on an infected host. Microfilariae mature inside the insect, which transmits them further to another final host.However, the life cycles of some species have not been completely elucidated. Harm caused by Onchocerca, symptoms and diagnosis Usually, most Onchocerca species that affect cattle do not cause clinical signs. Nodules may be palpable in the predilection sites of some species. Economic damage is mainly the consequence of carcass rejection at slaughter due to the repugnant nodules. Dogs infected with Onchocerca lupi may develop nodules as large as a bean in the sclerotic coat of the eye. Untreated infections can cause blindness. In horses, Onchocerca cervicalis and Onchocerca raillieti are non-pathogenic, but microfilariae can cause skin irritation. Onchocerca reticulata may cause chronic inflammation leading to calcification and lameness. Diagnosis depends on each species. Subcutaneous nodules can be identified through palpation, those in deeper organs are usually detected only after slaughtering. In horses, a full skin biopsy (>6 mm) properly macerated and stained may reveal microfilariae under the microscope. Prevention and control of Onchocerca There is little experience on how to prevent infections with these worms. Whatever reduces the population of midges and black flies - the intermediate hosts - will reduce the incidence in cattle or dogs. Protecting cattle against these vectors (e.g. with pour-ons containing synthetic pyrethroids) may reduce the number of infected cattle in a herd or the number of worms in an infected animal. Normally the use of anthelmintics is not indicated on livestock. No anthelmintic controls the adult worms. Nevertheless it is known that some macrocyclic lactones (e.g. ivermectin), levamisole, and diethylcarbamazine, a piperazine derivative, are effective against the larvae (microfilariae).