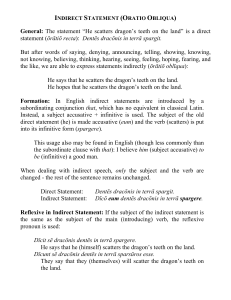

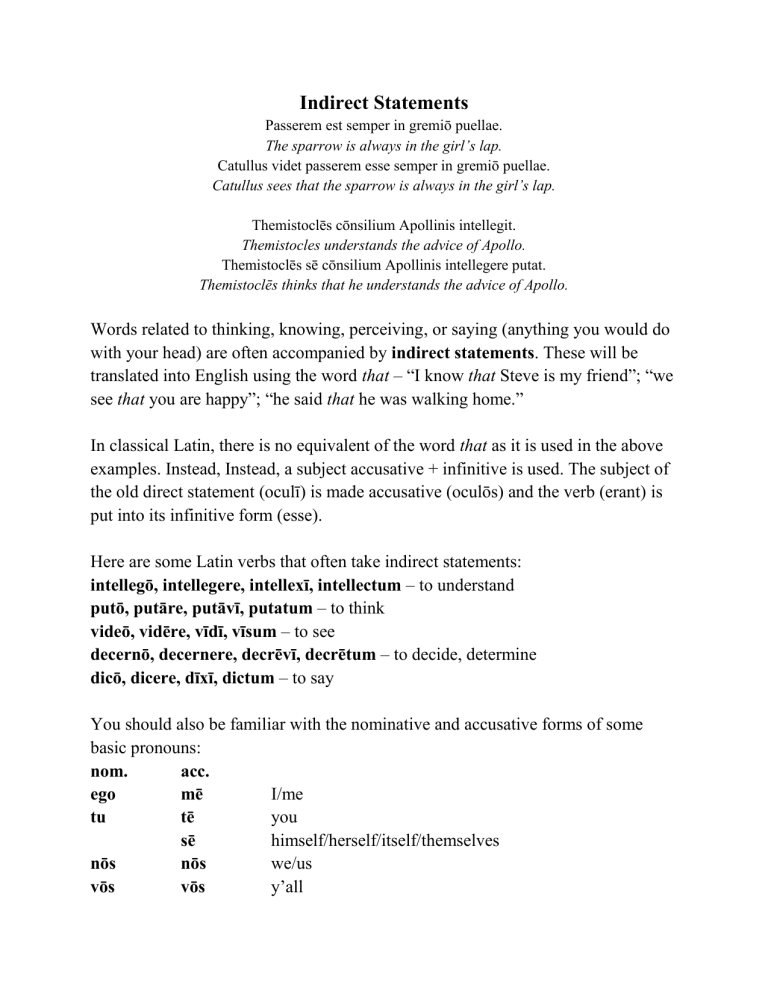

Indirect Statements Passerem est semper in gremiō puellae. The sparrow is always in the girl’s lap. Catullus videt passerem esse semper in gremiō puellae. Catullus sees that the sparrow is always in the girl’s lap. Themistoclēs cōnsilium Apollinis intellegit. Themistocles understands the advice of Apollo. Themistoclēs sē cōnsilium Apollinis intellegere putat. Themistoclēs thinks that he understands the advice of Apollo. Words related to thinking, knowing, perceiving, or saying (anything you would do with your head) are often accompanied by indirect statements. These will be translated into English using the word that – “I know that Steve is my friend”; “we see that you are happy”; “he said that he was walking home.” In classical Latin, there is no equivalent of the word that as it is used in the above examples. Instead, Instead, a subject accusative + infinitive is used. The subject of the old direct statement (oculī) is made accusative (oculōs) and the verb (erant) is put into its infinitive form (esse). Here are some Latin verbs that often take indirect statements: intellegō, intellegere, intellexī, intellectum – to understand putō, putāre, putāvī, putatum – to think videō, vidēre, vīdī, vīsum – to see decernō, decernere, decrēvī, decrētum – to decide, determine dicō, dicere, dīxī, dictum – to say You should also be familiar with the nominative and accusative forms of some basic pronouns: nom. acc. ego mē I/me tu tē you sē himself/herself/itself/themselves nōs nōs we/us vōs vōs y’all Try translating the following sentences that use indirect statements. intellegō Stephanum esse amicum meum. vidēmus te esse laetam. dixit sē domum ambulāre mater dicit periculum esse prope rīvum. Xerxēs se Graecōs vincere posse putat. Graecī Xerxem esse malum regem putant. Herōdotus dicit Xerxem militēs mare verbere iubēre. Atheniensēs putant Themistoclem esse callidum. Marcus se laborāre magnā cum industriā dīxit, sed ego Marcum esse in theatrō vīdī.