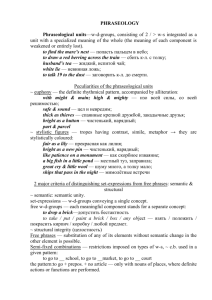

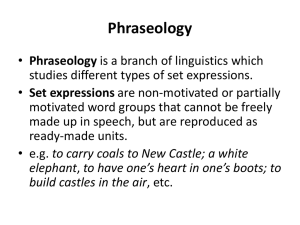

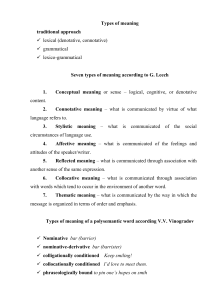

English Phraseology & American State Nicknames: A Linguistic Study

advertisement