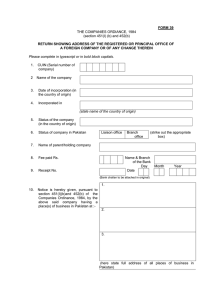

brief reports The press in Pakistan The daily arrest in April and May of this year of journalists protesting against the closure of the Lahore edition of the Musawat newspaper focussed world attention on the restrictions on press freedom in Pakistan. When sentences of whipping as well as imprisonment were imposed by Military Courts on some of those arrested, the reaction of outsiders was one of outrage. However, government action against journalists, as well as government control of the press by using a variety of devices, is not new in Pakistan; indeed, most of the instruments used by General Zia-ul-Haq's Martial Law regime to control or restrain the press were freely used by Mr Bhutto when in office and inherited by him from his predecessors Yahya Khan and Ayub Khan. The purpose of this article is to summarise the methods available for controlling the press and to indicate some of the ways in which they are now being used by the Martial Law regime, compared with Mr Bhutto's practice when in power. There are basically four different methods by which the content of the press is influenced or controlled by the government. First by ownership of newspapers, second by the application of economic pressure, third by the use of legal controls and sanctions on or against the printers and publishers of newspapers, and finally direct action against journalists as in the case of the Musawat protesters. It may also be that papers not in government hands are subject to direct censorship prior to publication. I have been told that army officers supervise the make-up of some newspapers but I have not been able to check this or to establish how widespread such control, if practised, is. I will accordingly concentrate on the four types of control set out above. The National Press Trust, which is a government-owned organisation, owns and operates directly a number of the more prominent newspapers. Among these are two of the three principal English-language newspapers, the Pakistan Times, which has the largest circula- tion, and the Morning News. In addition, it owns Urdu newspapers like Mashriq, which is published in the four provinces of Pakistan, and Imroz. Thus by direct control the government is able to reach a large section of the newspaper-reading public. In the elections of 1970 Mr Bhutto included in his campaign a promise to abolish the National Press Trust, recognising the risk to democracy arising from government ownership of a substantial section of the press. However, once in office the advantages of government ownership outweighed his election pledge. The National Press Trust is not now the only state owner of newspapers or printers. The newspaper Musawat was owned and controlled by the Bhutto family. It was published in two editions, one in Karachi and the other in Lahore, and was the biggest selling Urdu-language newspaper in Pakistan. It was the closure of the Lahore edition which led to the protests, arrests and floggings. Earlier, however, the Karachi edition also had to cease publication, but the cause and the circumstances were different. The presses on which the Karachi Musawat was printed were owned by the People's Foundation Trust controlled by the Bhutto family', headed by Begum Nusrat Bhutto. In addition to the Karachi Musawat these presses were used for printing a daily newspaper, Hilal-i-Pakistan, published in Sindi, and a weekly called Nusrat. This trust was taken over by the Martial Law regime along with the Zulfikan Ali Bhutto Trust, the formality of takeover being completed by means of President's Order Number 4 of 1978 made pursuant to the proclamation of Martial Law of 5 July 1977. The People's Foundation Trust was renamed the Sheikh Sultan Trust and all powers vested in a new board of trustees appointed by the President. One of the first acts of the new trustees was to refuse to print the Karachi Musawat and, being unable to find a new printer, the paper could not publish. The new trust has continued to print and publish Hilal-iPakistan and Nusrat. thus adding to the number of directly operated government newspapers. Economic pressure or control mainly takes BRIEF REPORTS two forms: the control of newsprint and the control of advertising. Both were used by Mr Bhutto when in power to favour those newspapers most sympathetic to his regime, and this kind of pressure continues today. The supply of newsprint is in the hands of the government, and those publications which do not follow government policy have in the past found their supplies cut off or only erratically available, sometimes with catastrophic results. During Mr Bhutto's years in office there was an extensive programme of nationalisation, one consequence of which was that a high proportion of the, major advertisers became state-controlled. Advertising revenue is an important source of newspaper income in Pakistan as elsewhere, and this was also used by the Bhutto government as a means of bringing pressure on the press. It remains true that many major advertisers such as Pakistan International Airlines and the big banks are state-controlled, so that those in charge of placing advertisements are likely to favour publications sympathetic to the government in power. This is particularly so where, as in Pakistan, political opinion is sharply divided. More fundamental to the control of the press is The Press and Publication Ordinance of 1963 introduced during President Ayub Khan's regime and replacing a similar Ordinance of 1960 and amended in 1975 and 1976 during Mr Bhutto's period in office. This Ordinance remains the prime instrument used to ensure that the press substantially reflects the regime's policies. The Ordinance imposes what is effectively a scheme for the licensing of newspapers and journals by requiring the printers and publishers of every newspaper to make a declaration in the prescribed form and making it an offence to print or publish unless such a declaration has been made. In addition to these provisions the Ordinance gives power to the government to require the deposit of security by the keeper of a press if certain conditions are fulfilled, with further powers to forfeit the security and close the press. It is significant that, by Section 67 of the Ordinance, these powers are not subject to challenge or question in any court and that many of them are exercised by the government, not on the basis of objective criteria, but solely where ' it appears to the government' that the conditions have been satisfied. Under the 1963 Ordinance every printer and publisher has to make a declaration in the prescribed form which must be authenticated by a District Magistrate. On reading the Ordin- 55 ance this looks like a formality, but the Magistrate must refuse to authenticate a declaration by a printer ' about whom the government is satisfied . . . that he is likely to act in a manner prejudicial to the defence of Pakistan or to use the press . . . for the purposes of incitement to the commission of any offence involving violence or for defamation '. In theory, the printer is entitled to be heard by the government before authentication is refused under this section, but in fact this enables the government to hold up almost indefinitely the authentication of a declaration and so prevent publication of a newspaper. Although the Ordinance refers to the provincial government, in practice control is firmly in the hands of the Martial Law regime through the Zonal (Provincial) Martial Law Administrators. The technique of withholding, or simply failing to deal with, applications for declarations was frequently used by the Bhutto government to deter unsympathetic newspapers. Section 23 of the 1963 Ordinance entitles the government, ' whenever it appears to the government ' that a press is used for printing any one of the matters set out in Section 24, to require the keeper of the press to deposit security of up to 30,000 rupees. The matters under Section 24 fall into 14 categories and include such things as reporting ' crimes of violence or sex in a manner likely to excite unhealthy curiosity ' and matters which amount to ' false rumours or to information calculated to cause public alarm, frustration or despondency ' or tending ' directly or indirectly to bring into hatred or contempt the government established by law in Pakistan or the administration of justice or any class or section of the citizens of Pakistan or to excite disaffection towards the government'. Under Section 24, where the printing press has been used for such matters, the government may either order the closure of the press or forfeit any security deposited under Section 23. Furthermore, there is nothing in the Ordinance to prevent repeated orders for the deposit of security, and indeed deposits of up to 100,000 rupees are often called for. The demand for security under the 1963 Ordinance by the Martial Law regime forced the Karachi weeklies Meyar, Al Fathe and Shah Jehan to cease publication. A demand for security is also sometimes used as a pre-condition for the authentication of a declaration. It must also be remembered that when a newspaper's printer is compelled under this procedure to stop printing it is not just a question of finding another printer but of finding a printer and then going 56 INDEX ON CENSORSHIP 5/1978 through the often lengthy and difficult process of his obtaining a declaration. The 1963 Ordinance is not the only statutory restraint on newspapers containing powers of closure and forfeit. Section 99A of the Criminal Procedure Code 1898 (as amended) enables the Provincial Government to forfeit publications where it appears to that government that they contain various things such as ' matters prejudicial to national integration' or matters which promote ' feelings of enmity or hatred between different classes of citizens '. An order under this Act may, however, be challenged in Court. Indeed, following the closure of the Lahore Musawat under these provisions — apparently because it published a statement made by Mrs Bhutto about the case against her husband in the Lahore High Court - proceedings were started in the Lahore High Court challenging closure. Musawat Karachi, had similarly been closed as a consequence of the publication of allegations by Mr Bhutto that the court trying him was biased. The actual arrest of journalists, sometimes with scant respect for precise legality, is no novelty in Pakistan. Prominent anti-Bhutto journalists like Mujibur Rehman Shami, Mohammed Salahuddin, and the Qureshi brothers were imprisoned by him before 1977, just as journalists such as Sayed Badruddin and Zaheer Kashmiri (editor and deputy editor of Musawat) and many leaders of the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ) have been arrested since, though they were subsequently released. There have been two new developments in the first few months of 1978. These were the widespread protests organised jointly by the PFUJ and the All-Pakistan Newspaper Employees' Confederation (APNEC), to which the Martial Law regime responded by arresting the journalists concerned under the Martial Law Regulations. These protests followed the closure of Musawat and took the form of daily attempts by groups of four journalists to launch a hunger strike. Each group was arrested, tried and convicted by a Military Court under Martial Law Regulation (MLR) 5 which prohibits public meetings, and 33 which prohibits political activity. MLR 33 is very widely drawn and bans publication of anything ' furthering the cause of any political party or politician ', ' likely to cause sensation or misunderstanding amongst the people or which is prejudicial to the precepts of Islam or the ideology or integrity or security of Pakistan ', or ' likely to cause dis- affection towards the Martial Law Administration or any martial law authority ' and ' arranging or holding any reception for any politician ' or ' in furtherance of the cause of a political party or politician '. MLR 33 carries a maximum sentence of seven years' imprisonment and/or 20 strokes. Two effects of the journalists' protests were the polarisation of opinion within the newspaper trade unions PFUJ and APNEC and the realisation by the Martial Law authorities that some compromise with the press was desirable. As a result a section of the Punjab Union of Journalists (PUJ) favourable to the regime entered into negotiations with the government for the re-opening of Musawat; no doubt they represented only a minority of journalists and perhaps their concern was as much with the unemployment faced by their members in consequence of newspaper closures as with freedom of the press. However, it also provided the government with the opportunity of acknowledging through its supporters the desirability, in principle at least, of some measure of press freedom. The concept may fairly be described as one of ' responsible dissent', and while this is a concept more appropriate to a benevolent autocracy than a democracy, at least the fact that dissent is accepted as possible may indicate that the Musawat protesters did not suffer in vain. However, it must also be recognised that there are subjects that are taboo in the Pakistan press and likely to remain so, not only because of possible government sanctions but also because of the self-censorship by journalists themselves. Thus there can be no discussion of the Islamic foundation of Pakistan, nor anything which may encourage the national aspirations of individual groups within the state - the structure of the country is too fragile and the memory of the secession of Bangladesh too recent for that. • J. Melville Williams Norwegian secrets case The September 1977 general election in Norway was accompanied by a controversy concerning alleged surveillance of Norwegian organisations and the Soviet bloc carried out from Norwegian soil by the CIA and Norwegian military intelligence. A Sosialistisk Venstreparti (Socialist Left Party) MP claimed during the election campaign that there was a secret agree-