Magical Realism & Alchemy in One Hundred Years of Solitude

advertisement

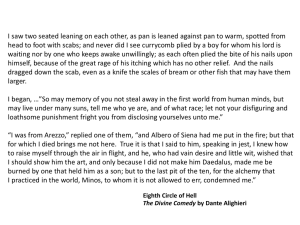

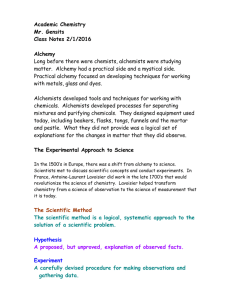

“A DVANCING IN THE O PPOSITE D IRECTION FROM R EALITY ”: O NE H UNDRED Y EARS OF S OLITUDE IS A DECODIFICATION OF THE NATURAL ORDER The novel deliberately undermines the trend toward rational objectivity. It presents the laws of the universe, not as if they were objective and self-evident facts, but instead as if they were unnatural and strange productions of man’s mind. Though Melquíades and José Arcadio Buendía, like other scientists, wonder at the profound mystery of reality, both men’s scientific quests are fuelled largely by alchemy rather than by modern science. The science García Márquez weaves into One Hundred Years of Solitude’s fabric is alchemy, while the age of modern technology stands outside of the magical realist world of the text. A LCHEMY AND MAGICAL REALISM Just as magical realism relies on the juxtaposition of two “realities”—the supernatural and the everyday—so too does alchemy rely on a dichotomy, that is, on its simultaneous physical and spiritual goals. Both alchemy and magical realism depend on the earthly as well as the “other-worldly.” The magical realist writer is an alchemist of words; he metamorphoses both the everyday and the supernatural until they meet on common ground. Alchemy reinforces the sense of a magically real world, stressing that what we know as science, Macondons believe to be magic, and vice versa. Melquíades brings the outside (specifically modern science) to the attention of Macondo not in order to clarify things but rather to mystify. The inhabitants of Macondo attempt to reconfigure the outside world into something magical as it invades the interior of the text and the town. One Hundred Years of Solitude makes no attempts to codify the magical; rather, in Macondo, it is reality that must be rationalized. the balance of the magical and the real is a necessity in Macondo. To do without reality is to go insane, as José Arcadio Buendía proves. Colonel Aureliano’s final solitude proves that to forego the supernatural is no less dangerous in Macondo than is José Arcadio Buendía’s loss of reality. ALCHEMY Among the many alchemists García Márquez creates in One Hundred Years, Melquíades stands out. He and his alchemy arrive on the first page, on the heels of the Buendía family. The home of alchemy in the text—Melquíades’s room—is also residence for, or connected with, many of the magical realist events that occur in the novel. Melquíades’s influence over the Buendías produces a long line of alchemists. the patriarch of the family, José Arcadio Buendía, is Melquíades’s first student. But his neglect of those miracles results in his ultimate failure. José Arcadio Buendía’s lost sense of time offers the most telling bit of evidence that he has failed as an alchemist. “Today is Monday, too,” Monday corresponds to silver, the “little work” of alchemy when compared to the “great work,” that is, the progression from silver to gold Aureliano can only be tempted away from the alchemy lab by two things: war and women. The gold fish he fashions, melts down, and then recreates in his old age seem to connect Aureliano symbolically to the quest for the philosopher’s stone, since the fish is a most common symbol for Christ, who is in turn frequently used in alchemical texts as a symbol of the philosopher’s stone. Next students were Aureliano Segundo And José Arcadio Segundo He shows the most promise as an alchemist. He is the only Buendía, in fact, to make Melquíades’s lab his permanent residence. As the sole survivor of the Banana Company massacre, he seeks solace in his work. o García Márquez describes José Arcadio Segundo through a series of alchemical references like Arab eyes. o Aureliano Babilonia deserves mention among the Buendía alchemists. Like Colonel Aureliano and the patriarch, José Arcadio Buendía, Aureliano’s alchemy is undone by his passion for a woman. He is the last in a long line of Buendía men who, for one reason or another, never fully experience complete and total immersion in alchemy. M ACONDO AS M ACROCOSM The creation and destruction of the Buendía line in Macondo can be considered García Márquez’s attempt at one “run-through” of the alchemical process. In this macrocosmic vision of One Hundred Years of Solitude, the characters must be the ingredients or “elements.” As an alchemist repeats his experiments in order to purify the process, Marquez shows that the impurity of Macondo (which is buendia’s incest) must be filtered out. C HARACTERS AS ELEMENTS Melquíades can be considered the materia prima of alchemy in the text. The many Aurelianos with gold in their names, are perhaps the most obvious. To begin the process, alchemist needed sulphur and mercury. The alchemical process has six stages. Although there were six generations, no result came out. Because they grow multiplicatively rather than spiritually. From one Aureliano spring seventeen golden sons; on the surface, then, it looks as though Macondo fulfills the cycle of alchemy. Instead, it is a multiplication that goes nowhere, since only one son will even live into his twenties. The Buendía line ends just as it begins—with an incestuous couple and their “golden” offspring. “Races condemned to one hundred years of solitude did not have a second opportunity on earth” Their failure to make the final alchemical leap suggests that the macrocosmic alchemy of One Hundred Years of Solitude will fail as well. Though the Buendía family fails, García Márquez succeeds in his literary alchemy. He creates a world where the believable is unbelievable and where the odd barely causes a stir. Magical realism suspends the fate of the Macondons by trapping them in a cyclical web from which they cannot escape. Macondo must, like the alchemists’ experiments, be redone, tried again, and refined.