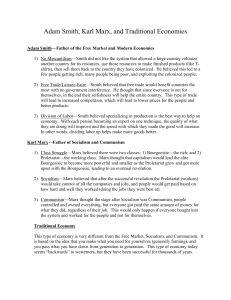

Mode of production In the Marxist theory of historical materialism, a mode of production (German: Produktionsweise, "the way of producing") is a specific combination of the: Productive forces: these include human labour power and means of production (tools, machinery, factory buildings, infrastructure, technical knowledge, raw materials, plants, animals, exploitable land). Social and technical relations of production: these include the property, power and control relations (legal code) governing the means of production of society, cooperative work associations, relations between people and the objects of their work, and the relations among the social classes. Marx said that a person's productive ability and participation in social relations are two essential characteristics of social reproduction, and that the particular modality of those social relations in the capitalist mode of production is inherently in conflict with the progressive development of the productive capabilities of human beings.[1] A precursor concept was Adam Smith's mode of subsistence, which delineated a progression of types of society based upon how the citizens of a society provided for their material needs.[2] Significance of concept Building on the four-stage theory of human development of the Scottish Enlightenment – Hunting/Pastoral/Agricultural/Commercial Societies, each with its own socio-cultural characteristics[3] - Marx articulated the concept of mode of production: “The mode of production inefficiencies within the broader socioeconomic system, most notably in the form of class conflict. The obsolete social arrangements prevent further social progress while generating increasingly severe contradictions between the level of technology (forces of production) and social structure (social relations, conventions and organization of production) which develop to a point where the system can no longer sustain itself and is overthrown through internal social revolution that allows for the emergence of new forms of social relations that are compatible with the current level of technology (productive forces).[9] The fundamental driving force behind structural changes in the socioeconomic organization of civilization are underlying material concerns—specifically, the level of technology and extent of human knowledge and the forms of social organization they make possible. This comprises what Marx termed the materialist conception of history (see also materialism) and is in contrast to an idealist analysis, (such as that criticised by Marx in Proudhon),[10] which states that the fundamental driving force behind socioeconomic change are the ideas of enlightened individuals. Modes of production Tribal and neolithic modes of production Marx and Engels often referred to the "first" mode of production as primitive communism.[11] In classical Marxism, the two earliest modes of production were those of the tribal band or horde, and of the neolithic kinship group.[12] Tribal bands of hunter gatherers represented for most of human history the only form of possible existence. Technological progress in the Stone Age was very slow; social stratification was very limited (as were personal possessions, hunting grounds being held in common);[13] and myth, ritual and magic are seen as the main cultural forms.[14] With the adoption of agriculture at the outset of the Neolithic Revolution, and accompanying technological advances in pottery, brewing, baking, and weaving,[15] there came a modest increase in social stratification, and the birth of class[16] with private property held in hierarchical kinship groups or clans.[17] Animism was replaced by a new emphasis on gods of fertility;[18] and (possibly) a move from matriarchy to patriarchy took place at the same time.[19] Asiatic and tributary modes of production The Asiatic mode of production is a controversial contribution to Marxist theory, first used to explain pre-slave and pre-feudal large earthwork constructions in India, the Euphrates and Nile river valleys (and named on this basis of the primary evidence coming from greater "Asia"). The Asiatic mode of production is said to be the initial form of class society, where a small group extracts social surplus through violence aimed at settled or unsettled band and village communities within a domain. It was made possible by a technological advance in dataprocessing – writing, cataloguing and archiving[20] - as well as by associated advances in standardisation of weights and measures, mathematics, calendar-making and irrigation.[21] Exploited labour is extracted as forced corvee labour during a slack period of the year (allowing for monumental construction such as the pyramids, ziggurats and ancient Indian communal baths). Exploited labour is also extracted in the form of goods directly seized from the exploited communities. The primary property form of this mode is the direct religious possession of communities (villages, bands, and hamlets, and all those within them) by the gods: in a typical example, three-quarters of the property would be allotted to individual families, while the remaining quarter would be worked for the theocracy.[22] The ruling class of this society is generally a semi-theocratic aristocracy which claims to be the incarnation of gods on earth. The forces of production associated with this society include basic agricultural techniques, massive construction, irrigation, and storage of goods for social benefit (granaries). Because of the unproductive use of the creamed-off surplus, such Asiatic empires tended to be doomed to fall into decay.[23] Marxist historians such as John Haldon and Chris Wickham have argued that societies interpreted by Marx as examples of the AMP are better understood as Tributary Modes of Production (TMP). The TMP is characterized as having a "state class" as its specific form of ruling class, which has exclusive or almost exclusive rights to extract surplus from peasants over whom, however, it does not exercise tenurial control.[24][25] Antique or ancient mode of production Sometimes referred to as "slave society", an alternative route out of neolithic self-sufficiency came in the form of the polis or city-state. Technological advances in the form of cheap iron tools, coinage, and the alphabet, and the division of labour between industry, trade and farming, enabled new and larger units to develop in the form of the polis,[26] which called in turn for new forms of social aggregation. A host of urban associations – formal and informal – took over from earlier familial and tribal groupings.[27] Constitutionally agreed law replaced the vendetta[28] - an advance celebrated in such new urban cultural forms as Greek tragedy: thus, as Robert Fagles put it, “The Oresteia is our rite of passage from savagery to civilization...from the blood vendetta to the social justice”.[29] Classical Greek and Roman societies are the most typical examples of this antique mode of production. The forces of production associated with this mode include advanced (two field) agriculture, the extensive use of animals in agriculture, industry (mining and pottery), and advanced trade networks. It is differentiated from the Asiatic mode in that property forms included the direct possession of individual human beings (slavery):[30] thus for example Plato in his ideal city-state of Magnesia envisaged for the leisured ruling class of citizens that “their farms have been entrusted to slaves, who provide them with sufficient produce of the land to keep them in modest comfort”.[31] The ancient mode of production is also distinguished by the way the ruling class usually avoids the more outlandish claims of being the direct incarnation of a god and prefers to be the descendants of gods, or seeks other justifications for its rule, including varying degrees of popular participation in politics. It was not so much democracy, but rather the universalising of its citizenship, that eventually enabled Rome to set up a Mediterranean-wide urbanised empire, knit together by roads, harbours, lighthouses, aqueducts, and bridges, and with engineers, architects, traders and industrialists fostering interprovincial trade between a growing set of urban centres.[32] Feudal mode of production The fall of the Western Roman Empire returned most of Western Europe to subsistence agriculture, dotted with ghost towns and obsolete trade-routes[33] Authority too was localised, in a world of poor roads and difficult farming conditions.[34] The new social form which, by the ninth century, had emerged in place of the ties of family or clan, of sacred theocracy or legal citizenship was a relationship based on the personal tie of vassal to lord, cemented by the link to landholding in the guise of the fief.[35] This was the feudal mode of production, which dominated the systems of the West between the fall of the classical world and the rise of capitalism. (Similar systems existing in most of the world as well.) This period also saw the decentralization of the ancient empires into the earliest nation-states. The primary form of property is the possession of land in reciprocal contract relations, military service for knights, labour services to the lord of the manor by peasants or serfs tied to and entailed upon the land.[36] Exploitation occurs through reciprocated contract (though ultimately resting on the threat of forced extractions).[37] The ruling class is usually a nobility or aristocracy, typically legitimated by some concurrent form of theocracy such as the divine right of kings. The primary forces of production include highly complex agriculture (two, three field, lucerne fallowing and manuring) with the addition of non-human and non-animal power devices (clockwork and wind-mills) and the intensification of specialisation in the crafts—craftsmen exclusively producing one specialised class of product. The prevailing ideology was of a hierarchical system of society, tempered by the element of reciprocity and contract in the feudal tie.[38] While, as Maitland warned, the feudal system had many variations, extending as it did over more than half a continent, and half a millennium,[39] nevertheless the many forms all had at their core a relationship that (in the words of John Burrow) was “at once legal and social, military and economic...at once a way of organising military force, a social hierarchy, an ethos and what Marx would later call a mode of production”.[40] During this period, a merchant class arises and grows in strength, driven by the profit motive but prevented from developing further profits by the nature of feudal society, in which, for instance, the serfs are tied to the land and cannot become industrial workers and wage-earners. This eventually precipitates an epoch of social revolution (i.e.: the English Civil War and the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the French Revolution of 1789, etc.) wherein the social and political organization of feudal society (or the property relations of feudalism) are overthrown by a nascent bourgeoisie.[41] Capitalist mode of production By the close of the Middle Ages, the feudal system had been increasingly hollowed out by the growth of free towns, the commutation for money of servile labour,[42] the replacement of the feudal host by a paid soldiery, and the divorce of retainership from land tenure[43] - even if feudal privileges, ethics and enclaves would persist in Europe till the end of the millennium in residual forms.[44] Feudalism was succeeded by what Smith called the Age of Commerce, and Marx the capitalist mode of production, which spans the period from mercantilism to imperialism and beyond, and is usually associated with the emergence of modern industrial society and the global market economy. Marx maintained that central to the new capitalist system was the replacement of a system of money serving as the key to commodity exchange (C-M-C, commerce), by a system of money leading (via commodities) to the re-investment of money in further production (M-C-M’, capitalism) - the new and overriding social imperative.[45] The primary form of property is that of private property in commodity form – land, materials, tools of production, and human labour, all being potentially commodified and open to exchange in a cash nexus by way of (state guaranteed) contract: as Marx put it, “man himself is brought into the sphere of private property”.[46] The primary form of exploitation is by way of (formally free) wage labour (see Das Kapital),[47] with debt peonage,[48] wage slavery, and other forms of exploitation also possible. The ruling class for Marx is the bourgeoisie, or the owners of capital who possess the means of production, who exploit the proletariat for surplus value, as the proletarians possess only their own labour power which they must sell in order to survive.[49] Yuval Harari reconceptualised the dichotomy for the 21st Century in terms of the rich who invest to re-invest, and the remainder who go into debt in order to consume for the benefit of the owners of the means of production.[50] Under Capitalism the key forces of production include the overall system of modern production with its supporting structures of bureaucracy, bourgeois democracy, and above all finance capital. The system’s ideological underpinnings took place over the course of time, Frederic Jameson for example considering that “the Western Enlightenment may be grasped as part of a properly bourgeois cultural revolution, in which the values and the discourse, the habits and the daily space, of the ancien régime were systematically dismantled so that in their place could be set the new conceptualities, habits and life forms, and value systems of a capitalist market society”[51] - utilitarianism, rationalised production (Weber), training and discipline (Foucault) and a new capitalist time-structure.[52] Socialist mode of production Socialism is the mode of production which Marx considered will succeed capitalism, and which will itself ultimately be succeeded by communism - the words socialism and communism both predate Marx and have many definitions other than those he used, however - once the forces of production outgrew the capitalist framework.[53] In his 1917 work The State and Revolution, Lenin divided communism, the period following the overthrow of capitalism, into three stages: First is the workers state, and then later, once the last vestiges of the old capitalist ways have withered away, Higher and Lower phase Communism which would actually have a socialist mode of production; These are known to most as Socialism and Communism. Marx typically used the terms the "first phase" of communism and the "higher phase" of communism, but Lenin points to later remarks by Engels which suggest that Marx's "first phase" of communism typically equates with what people commonly think of as socialism.[54] The Marxist definition of socialism is a mode of production where the sole criterion for production is use-value and therefore the law of value no longer directs economic activity. Marxist production for use is coordinated through conscious economic planning,[55] while distribution of economic output is based on the principle of to each according to his contribution.[56] The social relations of socialism are characterized by the working class effectively owning the means of production and the means of their livelihood, through one or a combination of cooperative enterprises, common ownership, or worker's self-management. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels deliberately wrote very little on socialism, neglecting to provide any details on how it might be organized on the grounds that, until the new mode of production had itself emerged, all such theories would be merely Utopian: as Georges Sorel put it, “to attempt to erect an ideological superstructure in advance of the conditions of production on which it must be built...would be un-Marxist”.[57] However, later in life, Marx pointed to the Paris Commune as the first example of a proletarian uprising and the model for a future socialist society organized into communes, observing: The Commune was formed of the municipal councilors, chosen by universal suffrage in the various wards of the town, responsible and revocable at any time. The majority of its members were naturally working men, or acknowledged representatives of the working class.... The police, which until then had been the instrument of the Government, was at once stripped of its political attributes, and turned into the responsible, and at all times revocable, agent of the Commune. So were the officials of all other branches of the administration. From the members of the Commune downwards, the public service had to be done at workmen's wages. The privileges and the representation allowances of the high dignitaries of state disappeared along with the high dignitaries themselves.... Having once got rid of the standing army and the police, the instruments of physical force of the old government, the Commune proceeded at once to break the instrument of spiritual suppression, the power of the priests.... The judicial functionaries lost that sham independence... they were thenceforward to be elective, responsible, and revocable... The Commune, was to be a working, not a parliamentary, body, executive and legislative at the same time...Instead of deciding once in three or six years which member of the ruling class was to represent and repress the people in parliament, universal suffrage was to serve the people constituted in communes, as individual suffrage serves every other employer in the search for workers, foremen and accountants for his business.[58] Communist mode of production Communism is the final mode of production, anticipated to arise inevitably from socialism due to historical forces. Marx did not speak in detail about the nature of a communist society, which he would describe interchangeably with the words socialism and communism. However, he did refer briefly in the Critique of the Gotha Programme to the full release of productive forces in "the highest phase of communist society [...] [when] society will be able to inscribe on its banner: 'From each according to his capacities, to each according to his needs'".[59] Different communities in specific society or country, different modes of production might come up and exist alongside each other, linked together economically through trade and mutual obligations. To these different modes correspond different in social classes and strata in the population. For instance urban capitalist industry might co-exist with rural peasant production for subsistence and simple exchange and tribal hunting and gathering. Old and new modes of production might combine to form a hybrid economy. However, Marx's view was that the expansion of capitalist markets tended to dissolve and displace older ways of producing over time. A capitalist society was a society in which the capitalist mode of production had become the dominant one. The culture, laws and customs of that society might preserve many traditions of the preceding modes of production, thus although two countries might both be capitalist, being economically based mainly on private enterprise for profit and wage labour, these capitalisms might be very different in social character and functioning, reflecting very different cultures, religions, social rules and histories. Elaborating on this idea, Leon Trotsky famously described the economic development of the world as a process of uneven and combined development of different co-existing societies and modes of production which all influence each other. This means that historical changes which took centuries to occur in one country might be truncated, abbreviated or telescoped in another. Thus, for example, Trotsky observes in the opening chapter of his history of the Russian