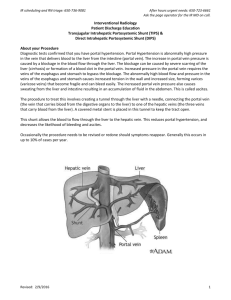

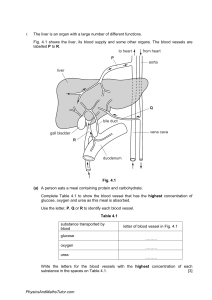

The Liver disease. Surgical anatomy and physiology. The dual afferent blood supply, consisting of the hepatic artery and portal vein, singles out the liver from all other organs. That the portal vein has no valves is the understanding of portal hypertension. The blood in the sinusoids is derived from two sources: 1. The portal system conveys between 60 and 80 % of the afferent blood to the liver. 2. The hepatic artery, which supplies 25% of the 1500-ml blood that enters the liver each minute, provides oxygen for the liver. The pressure relationship of the hepatic artery (100 – 150 mm Hg), the portal vein (8 –12 mm Hg) and the hepatic veins (1-4 mm Hg) testify further as to the unique nature of the circulation through the liver. During exercise the blood flow through the liver, normally about 40% of the cardiac output, falls sharply in favor of the heart, brain and muscles. Surgical lobes of the liver. The right and left branches of the hepatic artery do not supply the two main anatomical lobes as such. Their territory has a boundary running along the gall – bladder bed. The biliary ducts and branches of the portal vein follow the hepatic arterial branches. In this way, the liver is divided in to two surgical lobes, right and left, by a major avascular fissure. The blood from the liver is drained by three major hepatic veins: right and left, the middle one of which is located in the major fissure. Knowledge of the anatomy of the surgical lobes and of the segments is particularly important in planning hepatic resection for injury or tumors. Segmental structure of the liver. Now that resection of primary and secondary tumors of the liver is regularly performed, more detailed segmental anatomy of the liver is needed. One or two segments may be resected leaving the blood supply and bile drainage of the other segments undisturbed. As much as whole lobe plus two other segments can be removed, providing two healthy segments are spared. Intaoperative ultrasound is used to detect the vessels and ducts inside the liver. Functions of the liver. 1. The formation of the bile and the metabolism of bilirubin and of bile salts. 2. The synthesis of albumin, fibrinogen, and prothrombin. 3. Storage and metabolism of carbohydrates, including the conversion monosaccharides (e. d. dextrose) into glycogen, and vise versa. 4. Formation of phospholipids and cholesterol, synthesis of fatty acids from carbohydrate, and other steps in fat metabolism. 5. Desamination of amino – acids with formation of urea. Removal of ammonia from portal blood. 6. Heat production. Intermediate metabolism, both anabolic and catabolic, in the liver requires a large amount of energy derived from the conversion of adenosine triphosphate (ATF) to adenosine diphosphate (ADR) as well as aerobic oxygenation via the Krebs cycle. A byproduct of these activities is the production of an excessive amount of energy in the form of heat. 7. Reticuloendothelial activities. 8. Storage of vitamin B12 (cyancobalamin) and vit. A. 9. Iron and copper storage. 10. Destruction of bacteria. 11. Detoxication of drugs and hormones. Regeneration. Unlike other organs, the liver possesses a completely by compensatory cellular hypertrophy and hyperplasia. Special methods of liver investigation. Usually several tests are undertaken in each patients, and in some instances the individual test must be repeated. No less than 80 %of the liver can be out of action without affecting individual tests, and in patients with cirrhosis they may be within normal limits. Among a large number of tests available the following are the most useful: I. 1. Serum bilirubin estimation. 7 mmol/ l (0.4 mg) 100 ml, 2. Serum alkaline phosphatase. [N = 3 – 13 king - Armstrong (K- A), 5 – 30 iu/ l, ar 1.5 – 4 Bodansky units.]A high alkaline phosphatase (>40 KA units or > 100 in/l) with low transaminase levels favors obstructive jaundice but the alkaline phosphatase can be high in cholestatic jaundice and hepatitis. 3. Estimation of serum albumin is a good general test of hepatic function. A level below 25 g/l (2.5 / 100 ml) indicates that liver function is greatly impaired. Above 30 g/l (3.0 g/ 100 ml) is satisfactory and safe. 4. Serum transaminases (aminotransferase). In creased values (over 100 units) are found in hepatocellular disease. 5. Plasma prothrombin index, if low is an indication for preoperative vitamin K therapy. 6. 5–nucleotidase and - glutamynly transferase is raised particularly in alcoholic liver disease. II. Liver biopsy is a common procedure of: considerable diagnostic value. III. Imaging techniques. A. Noninvasive methods: a. A plain x- ray of the abdomen is only of limited diagnostic value (calcification). b. Ultrasound. This is a safe, simple and noninvasive method that is of particular value in demonstrating dilatation of bile ducts and stones in the gallbladder as well as primary and secondary liver tumors and cysts. c. Computed axial tomography. This is of considerable value in showing the nature and relations of tumors and cysts in the liver. (Expansive). d. Radioactive scanning. A gamma emitting isotope such as 198 colloidal gold and Techetium 99 is taken by the reticuloendothelial system and can be useful in local lesions in the liver. Rose – Bengal labeled with 131 I is taken up by the liver parenchyma. The normal liver presents as even distribution of activity, and lesion that do not take up isotopes, e. d. abscesses, cysts and tumors, appear as defects in the scan. Generalized decrease in up take suggests a diffuse hepatocellular disorder such as cirrhosis. B. Invasive methods: a. Angiography by means of coeliac axis or superior mesenteric arteriogram can show vascular obstruction or an avascular lesion, or a vascular tumor. In case of portal hypertension films in the venous phase of superior mesenteric angiography are useful. Splenic punctures are more hazardous but if a fine needle is used it is an acceptable alternative. b. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (RTC). c. Endoscopic retrograde cholangeopancreatography (E R C R). Hydatid Disease of the Liver. Although the larval stage of the parasite Echinococcus granulosus can thrive in many parts of the body, in 80% of cases it does so in the liver; after ingestion it enters this organ through a radical of the portal vein, and usually the right lobe is affected. Source of infection. Dogs are the chief mediators of hydatid disease to human beings by direct contact. Humans may also eat salads on which the ova hake been deposited. Animals, particularly sheep, are infected by eating contaminated grass. Once in the stomach, the ova burrow through the stomach wall to enter the portal system and the liver. Dogs become infected by feeding on offal of infested sheep. The disease is relatively common in the sheep - rearing districts of Australia and South America, Greece, Turkey, Iran and Iraq. In other parts of the world the life – cycle can be completed in other animals: the wolf → moose → wolf ( in the frozen north ) often maintains the cycle. Pathology A hydatid cyst consist of thee layers. 1) The adventitia (pseudocyst), consisting of fibrous tissue, the result of reaction of the liver to parasite, is grey in color and blended intimately with the liver, from which it is inseparable. 2) The laminated membrane (ectocyst) formed of parasite itself is whitish and elastic and contains the hydatid fluid. The membrane peels readily from the adventitia. Hydatid fluid is crystal – clear, contains no albumin. The cyst grows very slowly. 3) The only living part of the hydatid cyst is a single layer of cells (germinal epithelium) lining the cyst (endocyst). This secreted: a) internally: the hydrated fluid; b) externally: the laminated membrane. Brood capsules within thy cyst develop from the germinal epithelium and are attached by pedicles to its innermost wall. Within the brood capsules, scolices (heads of the future worms) develop. Should the laminated membrane become damaged, it disintegrates, and the brood capsules, becoming free, grow into daughter cysts. In this event the mother cyst ceases to exist as such, the hydatid fluid and its content being confined by the adventitia only. Clinical features. For a long time, perhaps for some years after the original infestation (which often occurs in childhood), a hydatid cyst remains symptomless. In the course of time a visible and palpable swelling in the upper abdomen is discovered. An unruptured cyst present as a rounded calcified shadow in the liver. Ultrasound and CT scanning can localize the cyst and ERCP can show the cyst communicates with bile duct. The intradermal test (Casoni’s test) is positive in 75 % of cases, but gives up to 40% of false positives. Recent serologic tests are of greater accuracy be indirect haemagglutination reaction. A blood count often shows an eosinophilia (6% or more). Course of the disease. 1. Occasionally the parasite dies. The fluids absorbed, and all that remains is encapsulated, laminated, bile – stained membrane the walls of the cyst may calcify. 2. Usually the cyst enlarges gradually and becomes manifest by its size. Sometimes sessile cyst float in the peritoneal cavity, or they may be confused with mesenteric, pancreatic or renal cysts. 3. Complications arise. Complications: a/Jaundice: → due to pressure of cyst on the biliary ducts. → due to cyst within the bile ducts. b/ Rupture → in to peritoneal cavity. →in to alimentary canal. →in to the biliary channels the most common complication. →in to a plural cavity. Rupture into the peritoneum is accompanied by profound shock, and all the signs of diffuse peritonitis. As with any of rupture of a hydatid cyst, anaphylactic phenomena, notably urticaria, are prone to occur. The treatment of intraperitoneal rupture must be immediate, and directed to combating shock and cleansing the peritoneal cavity. Even in those who survive, the ultimate prognosis is poor, for if, as is usual, the cyst contains brood capsules, however meticulous the cleansing the disease tends to become disseminated within the peritoneum. c/Suppuration. Treatment of hydatid cyst of the liver Small cysts do not require treatment. For larger cysts surgical treatment is required because there is no safe effective medical treatment. Recently the mebendasole, in doses of 400 to 600 mg three times a day for 21 to 30 days, has been found to be effective in some patients. Operation. The cyst is exposed by an incision that gives the best access. Abdominal packs, wrung out in solutions of either hypertonic sodium chloride (23 – 30 %) or sodium hydrochloride (0,5 %) are tucked around the exposed liver. The cyst is aspirated; a scolicidal solution (e. d. hypertonic saline solution or sodium hypochloride solution) is injected so as to render the cyst about three – quarters full. An incision is made through the liver overlying the cyst, and the adventitia is opened. The laminated membrane is separated from the adventitia with a finger. The aim should be to deliver the cyst intact. When the intact cyst can be enucleated, the resulting cavity in the liver can be closed completely. In less favorable circum stances, it is advisable to drain the cavity, particularly when infections present when the contents of the cyst are bile stained, or when there is uncertainty of its complete removal. Every precaution must be taken to prevent spilling the contents of the cyst into the peritoneal cavity or the layers of abdominal wall, otherwise dissemination is lively. Where there are larger or multiple cysts, partial hepatectomy may be necessary. Mebendazole is recommended postoperatively to present recurrence. Cirrhosis Of Liver Hepatic cirrhosis is a necrosis of the liver followed by fibrosis and regeneration of liver cells and involving the whole organ. Portal Hypertension Aetiology: increase of the portal vein blood pressure is due to an obstruction which can be: (1)prehepatic, (2)intrahepatic, (3)posthepatic. 1. Prehepatic. About 20% of patients belong to this group the patients with prehepatic portal obstruction is nearly always young and often a child. The most usual cause of for advice is being sought is either a sudden hemorrhage or listlessness due to anemia. On examination : liver is not palpable ,spleen is obviously enlarged. The anemia usually due to oozing from esophageal varices but sometimes hypersplenism is a factor .As the liver is normal ,or nearly so, liver function test remains normal as disease advanced. Ascites does not occur unless there is active phlebitis in the portal vein .The obstruction arises in the one of two ways : (a) There is congenital abcenss or abnormality of the portal vein. (b) Thrombosis of the portal vein due to extension of the normal obliterative process of the umbilical vein and ductus venosus sometimes associated with omphalitis in newborn. (c) Obstruction of portal vein in adult may be due to chronic pancreatitis and carcinoma of the pancreas or thrombosis of the vein may followed by acute pancreatitis ,but these may just thrombosis the splenic vein may follow acute pancreatitis. The vein becomes replaced by a mass of collateral channels. 2. Intrahepatic accounts for nearly 80% of all cases. The causes are cirrhosis (fricvently alcogolic in origin) and schistosomiasis in which blood flow through the liver is obstructed. Enlarged portosystemic venous communications are present long before serious oesophageal hemorrhage occurs. Oesophageal varices can be demonstrated radiologically or seen through oesophagoscope. Enlargement of veins of abdominal wall radiating from umbilicus may be present. As long as hypertrophy of liver tissue is sufficient to compensate for the cellular destruction by cirrhosis, the liver function tests remain within normal limits. 3.Posthepatic is rare. It may be caused by: (a) constrictive pericarditis and tricuspid valve incompetence and it is also a component of the Budd-Chiari syndrome. This syndrome is result from obstruction of the hepatic veins. (b) Spontaneous thrombosis of the hepatic veins or neoplastic encroachment from other organs account for the majority of cases .The syndrome is also associated with clotting disease especially polycythaemia and the use of hormones for contraception and infertility. Some cases, presumably congenital are caused by an obstruction of the suprahepatic portion of the inferior vena cava with a membranous web. The importance lies in its potential curability by operation. Collateral circulation .When there is obstruction of blood flow to or from the liver, the body responds by opening up normally insignificant anastomotic channels. When the obstruction is prehepatic, collaterals between the portal vein above and below the obstruction enlarged. Depending upon the site of the obstruction, some of the collaterals between the portal and systemic venous systems, notably the oesophageal plexus, also becomes dilated. When the obstruction is intrahepatic, anastamotic channels outside the liver between the portal and systemic systems become engorged, dilated and so an increasing proportion of the obstructed portal venous blood bypasses the liver. The only dilated veins which are dangerous to life are those in the submucosa of the oesophagus and upper end of the stomach. In patients with portal hypertension hemorrhoids, if present are usually of the idiopathic type but rectal varices are common and can lead to severe haemorrhage. Anastamoses between The portal and Systemic venous system. Sites of anastomos. Portal vessels Systemic vessels Signs and Symptoms 1 . Plexus around Oesop hg. lower End branches Lower systemic Haema temesis or melena of of left oesophageal oesophagus gastric veins vein & short Gastric veins 2 . Around umbilicus Parau Superfici mbilical al veins of veins anterior (accompan abdominal y the wall caput medusae round Ligament of the liver) 3 . Plexus Superi Middle around or and inferior lower Third haemorrho haemorrhoida of rectum idal veins l veins and Rectal varices (heavy bright red bleeding) Anal canal 4 . Extrape ritoneal Tribut aries of superior and Subdiaph ragmatic and silent Surface s of abdominal inferior retroperitonea mesenteric l veins vein Organs Oesophageal varices are dilatations of the normal submucosal oesophageal veins and are the most important collaterals of the portal circulations. They may extend from below the gastro-oesophageal junctions for 10-15cm up to oesophagus. Bleeding, which is nearly always from the lower 5cm of the oesophagus may be slow ooze or sudden and severe. The presence of oesophageal varices can be demonstrated by several methods but it cannot be assumed that they are the site of bleeding without investigation. 1. Fibrooptic or rigid oesophagoscopy will demonstrate them in all cases ,and should be carried out along with gastroscopy to confirm the presence of varices and determine if they are the source of bleeding .If the lower oesophagus is full of fresh blood it may be impossible to see varical bleeding. • Duodenal and gastric lesion. • Reendoscoping an hour or two after. 2. Radiology after a barium swallow will show filling defects but endoscopy is far more accurate. The presence of varices and the cause of the portal hypertension ,e.g.: portal thrombosis or cirrhosis can be demonstrated by angiography .The venous phase of a celiac angiogram is now preffered to direct puncture of the spleen. Treatment of massive hemorrhage from oesophageal varices. By the time patients reach hospital about 1/3 will have stopped bleeding heavily. There are 4 stages in management : 1. Resuscitation of the patients. -Ensure a clear airway and rapid replacement of blood volume is the priorities. Fluids containing sodium should be avoided because patients with liver diseases retain sodium excessively and great care must be taken with sedation as opiates and the tranquilizers are normally metabolized in the liver. 2. Arrest of haemorrhage. (a) Tamponade is the most direct and reliable method of arresting hemorrhage if carried out carefully by an experienced team. A Sengstaken-Blackmore type of tube with gastric and oesophageal balloons is the most commonly used . Which ever is used there must be some method of aspirating saliva from the oesophagus to prevent inhalation pneumonia. The gastric balloon should be inflated with 300-400 ml of air to ensure that the tube does not fall out and to compress the varices round the upper part of the stomach. The oesophageal balloon is inflated to a volume which was found before insertion to procedure an even distention. The pressure should be 20-30mm Hg above that recorded before insertion .The tube is secured to the forehead to prevent if advancing into the stomach but strong traction is unnecessary .The tube is kept in position until the bleeding point is treated. This should not be more than 24 hours, preferably 12 hours. (b) Drugs. Vasopressin (20 IU in 200 ml i.v. over 20 min. and then 0.4 U/minute for up to 24 hours) may be used to lower portal venous pressure and so reduce bleeding (side effect : abdominal gripping ; coronary artery vasoconstriction). The hormone somatostatin is effective in lowering intravariceal blood pressure and flow. Morphine is contraindicated. (c) Endoscopic ligation of esophageal varices: - The varix is drawn into the ligator by suction. An “O” ring is applied. (d) Endoscopic sclerotherapy is now the simplest and relatively safe way of treating hemorrhage from esophageal varices and stops bleeding in over 90% of cases. Technique. A fibroptic flexible oesophagoscope . Sedation with pharyngeal analgesia. Blood will be sucked away while the injection needle is in place. 1) In the intravariceal method: 5-6 ml of ethanolamine oleate or other sclerosant is injected in each varix at or just above the gastroesophageal junction to produce thrombosis. 2) In the paravariceal technique : very small quantities (0.5 ml) of sclerosant is injected in many different sites along side each varix to produce perivascular fibrosis Ballon compression maybe used for a short time afterwards.Sclerotherapy may be repeated the following day. 3/ combined method. (d) Operations. Emergency operations are avoided if possible because of the high mortality; but if bleeding persists after sclerotherapy there is no alternative. There are 2 alternatives: devascularization and transection or portosystemic shunting. Devascularization and transection operation. The Miles-Walker and Borema-Crile procedures were transthoracic operations and involve direct ligation of veins in the oesophagus and Tanner’s porto-azygos disconnection used as abdominal approach with transaction of the upper stomach. Combined devascularization transection operation where upper half of the stomach and lower part of the oesophagus are devascularised and then the gastro-oesophageal junction transected and reanastamosed, thereby interruption in intramural and submucosal veins. The devascularisation must be continued well up the oesophagus even an abdominal incision is used. Oesophageal stapling(Johnston). The stapling gun makes the transaction and reanastamosis relatively easy. To pass a stapling instrument into the lower oesophagus through a small hole in the anterior wall of stomach. When operated ,the instrument simultaneously divides the oesophagus and joins it together again with staples which occludes the vessels .The results of this operation are reasonably effective and it has the merit of simplicity. Portal vein shunt. The operation is not easy. It is best avoided in the presence of active bleeding except by very experienced surgeons. Portasystemic shunt operations. Premilinary investigation should have determine the cause of the venous block and its site. Portalcaval anastamosis: a) end- to- side portacaval shunt b) side-to-side portacaval anastomosis. With careful selection of cases the mortality of an elective portacaval operation is about 6% and recurrent bleeding from varices after this operation is most unusual. Up to 30% of patients may have post shunt encephalopathy because of venous deprivation the liver and slow deterioration of the liver function. (c) Splenorenal anastomosis. This may be performed if there is thrombosis of the portal vein, but it is contraindicated if the splenic vein is less than 1cm in diameter. This operation is less effective than a portacaval anastomosis in preventing further hemorrhages, but carries a lower risk of encephalopathy. The spleen is removed .The splenic vein is anatomized by end-toside anastomosis with the renal vein. Distal splenorenal shunt (DSRS). The distal splenic vein is joined to the renal vein without splenectomy. (d) Superior mesentericocaval anastomosis. When the portal vein is thrombosed this alternative may be possible. The inferior vena cava is divided .The proximal end is joined to the side of the superior mesenteric vein in the root of mesentery. (e) Splenectomy. This has no place in treatment of portal hypertension except in the rare cases of thrombosis confined to the systemic vein or in combination with some other operation. General management of patients. Stopping the bleeding is the first priority but the general state of the patient must not be forgotten and the earlier support measures are started, the better the outlook. (a) Encephalopathy. Absorption of protein metabolism from the alimentary tracts leads to encephalopathy .The bowel should be cleared of blood by enemas or purgatives (e.g. magnesium sulphate). In addition neomycin are given by mouth or tube to alter and reduce the proteolytic bacteria in the gut. (b) Corrections of clotting problems. Vitamin K is given to correct the abnormal prothrombin time. Table: Child’s table indicating suitability of a patient with portal hypertension for shunt surgery Observations Very suitable , Marginal , B Unsuitable ,C A Serum bilirubin mmol(mg %) Below 34 34-50 (2.0) Serum albumin (2.0-3.0) Over 35 30-35 g/l (mg %) (3.5) Ascitis None Neurological Over 50 (3.0) Below 30 (3.0-3.5) (3.0) Easily Poorly controlled controlled Minimal Coma Good Poor None disorders Nutritional status Excellent Preventing of rebleeding Long term treatment: (a) Repeated sclerotherapy with regular check endoscopies at 2 weeks, 1 month, 3 months and then 6 month, to diagnose and sclerose non thrombosed varices or new varices that develop with time. (b) Devascularization and oesophageal transaction. (c) Portasystemic shunts. Transjugular intrahepatic portasystemic shunt ( TIPS). TIPS is placed via the right internal jugular vein. The right hepatic vein is catheterized and a needle is punctured through the hepatic parenchyma to enter the main right portal vein. A balloon is placed over a guide wire to dilate this parenchymal tract and finally, a metallic stent is placed in the dilated tract. Stents must bridge all the parenchyma between the portal and hepatic veins but not protrude significantly into either of the veins. Portography before and after stent placement should document both flow patterns to the liver and varices, as well as measuring pressure. The portal to hepatic pressure gradients should be reduced to < 12mm Hg. Currently, the wall stent, a self expanding stent is the most widely used. The risk for this procedure are similar to the risks for any portal systemic shunt with bleeding, infection and precipitation of liver failure as the main risks. As with other minimally invasive surgical procedures, hospitals stay can be shortened. Immediate fluid management, antibiotic coverage, liver functions monitoring guidelines should be followed strictly. The major problem with TIPS at this time is stenosis or occlusion of the shunts in the first 6 months. Liver transplant. The final surgical approach to portal hypertension and variceal bleeding is liver transplantation. However, the indication for transplantation is end stage liver disease, not variceal bleeding. The decision to proceed to transplantation should be based on full evaluation following stabilization of initial bleeding. Quantitative liver function testing can help make this definition. The Child-Pugh class C patient with variceal bleeding may require liver transplantation. The benefits of liver transplantation in the patient with variceal bleeding and end stage disease is that it not only decompresses the varices and controls bleeding but also restores functional hepatic mass. The disadvantage is that liver transplantation requires long term immunosupression with its associated morbidity. However, survival rate achieve in this patient subset are significantly better than the outcome historically achieved with other forms of therapy. Management Algorithm of varicceal bleeding. Acute variceal bleed sclerotherapy EVALUATION Good liver function Poor liver function Non-alcoholic disease Alcoholic cirrhosis Transplant candidate SCLEROTHERAPY + B- BLOCK No Yes DSRS Transplant TIPS Transplant candidate DSRS – Distal splenorenal shunt TIPS - Transjugular intrahepatic portocaval stent shunt Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt Portal hypertension TIPS-transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. TIPS is placed via the right internal jugular vein.The right hepatic vein is catheterized and a needle is punctured through the hepatic parenchyma to enter the main right portal vein.A ballon is placed over a guide wire to dilate this parenchymal tract and finally ,a metallic stend is placed in the dilated tract.Stends must bridge all the parenchyma between the portal and hepatic veins but not protrude