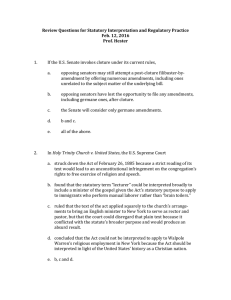

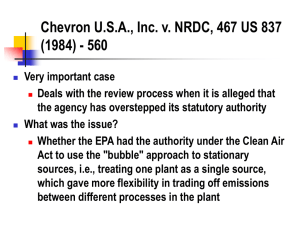

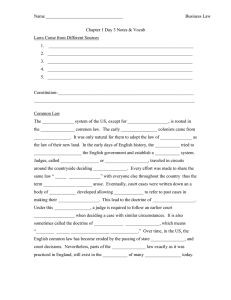

Theories of Interpretation Intentionalism “what was in congress’s mind” - narrow - faithful agent of the legislature Method Problems Arguments Legislative history and context There could be more than one intent The legislative history shows Congress intended … Purposivism “what was congress’s purpose in enacting the statute” - broad (1) purpose of the statute – reason they did it/mischief to be avoided - can consider context New Textualist “historically frozen definition” Economic (ex ante) (1) Look for the ordinary public meaning of the word in the statute at the time it was drafted (specific term or whole code) – apply the ordinary meaning If the language of the statute is plain and unambiguous, we do not need to look further than the words themselves, unless such an interpretation produces an absurd result. (2) in rare cases depart from the textual meaning (a) the literal meaning is absurd, court provides an alternative meaning - legislative history just to confirm the meaning is absurd - Don’t use extrinsic evidence to get meaning (b) Provide meaning though the least violence to the text 1. Facts 2. Interpret the statute a. words b. apply facts c. check precedent Fix a problem, court made a mess. Resolve a difficulty. Literalist Can be more contextual - can be read as it is today Pragmaticism (ex post) Dynamic Interpretation Aggressive Partnership: court keeps the law relevant (2) apply the facts to the purpose (3) will the language support/bear it (extending it past what they possibly could have intended) The dynamic approach encourages judges to be more flexible and consider what the enacting legislature would have wanted when and social moral value changes. There is a problem that needs to be fixed and the court should fix it. There could be more than one purpose and those purposes can conflict. How do you get the meaning from the past. We are interpreting in the present The court's duty is to discern the intent of the representative body and interpret statutes to further that intent. The judicial role is to be a faithful agent of the legislator, working to ensure that legislative policy choices are implemented. Courts must read a statute in context, and according to the purpose it serves because a statute only makes sense in light of its purpose. Purposivism renders statutory interpretation adaptable to new circumstances. Whole Rule Act Language and Grammar Cannons The Whole Act Rule It is Congress's job not the judiciary to change the statute . If Congress meant that then they would have changed it. Legislature's choose the words in a statute to express their intent. Dictionaries If Congress meant that then they would have said it. Too literal Amelia Bedelia problem Criticized as Judicial activism or Judicial power grabbing Criticized as Judicial activism or Judicial power grabbing The court failed to consider this situation. Therefore, the judge would craft a solution that accords as much as possible with the purpose. P1 P2 Tools of Statutory Interpretation: Plain Meaning: Interpret the statute according to the plain meaning you can extract from the language of the statute itself. The words mean, what they mean. Problems: Everyone understands the meaning differently. Language itself is ambiguous. People will interpret the meaning and context differently. Language evolves with time so the meaning of words are constantly changing. *Uses dictionaries*/ Counter – dictionary definitions are acontextual, meaning requires context. Ordinary Meaning: Typically, courts will assume that the legislature uses words in their ordinary sense. What the words convey to the ordinary and reasonable reader? Problems: there could be more than one ordinary meaning. Language is ambiguous and requires context to define it. Another criticism is that dictionaries are just historical recollections of how language is used. *Uses dictionaries and google searches* Technical Meaning Super Strong Stare Decisis: Courts are reluctant to overturn power judicial decisions absent of the reason to do so. Story decisis further certainty in the law and faith in the judicial system. It provides the appearance of objectivity. ex ante: To evaluate a rule based on whether it sets up a legal directive that will be good for the average case and provides proper incentives for the citizenry and not because you like its result in a particular case (People understand the rule before they act. Judges read as written). ex post: To evaluate a rule based on making the result fair or prevent needless hardship upon a sympathetic claimant in a particular case (interpret after they act. No one knows the real before they act. Case specific). Coherence with Public Norms: Judges have a duty to add coherence to the body of law with their decisions, requiring them to infer, as much as possible, that the legislature is not directing a departure from a generally prevailing principle or policy of the law. Language Cannons: Noscitur a Sociis: It is known from its associates. In determining the meaning of an ambiguous word you should reference the words associated with it to give it meaning. (Helps to give meaning based on the other words in the same string). Ex: Jarecki, “exploration, discovery, or prospecting” Can conflict with the rule against surplusage. Noscitur a Sociis directs that word share meaning, while the rule against surplusage directs that each word should have a different meaning. Edjusdem Generis: Of the same kind, class, or nature. Where general words follow specific words in a statutory in numeration, the general words are construed to embrace only objects similar in nature to those objects enumerated by the preceding specific words. (Of the same kind or class) Ex: Circuit City, “seamen, railroads, employees, or any other class of workers engaged in commerce” - only applies to transportation Reverse Edjusdem: broad define the specific The point of this Canon is to narrow down general or “catch-all” phrases at the end of a list (“and all others”). Identify the attribute that the listed items share so you can interpret the “catch-all” to be of the same type as the items listed. Expressio Unius: Words admitted may be just as important as words set forth. Expression or inclusion of one thing indicates exclusion of others. (Excludes those not listed) Ex: Holy Trinity They are excluded because they're not specifically included and there is no general word or catchall phrase following the list. Whole Act Rule: Statutory language should be interpreted in the context of the code as a whole. Language is used consistently, every time it is used it means the same thing (Consistent usage). Whole Code Rule: looking at multiple statutes. Meaningful Variation: If the legislature uses a word in one part of an act or a related act, then changes to a different word in another part of the same or related act, the legislator intended to change the meaning. (Counter to the Whole Rule) Consistent usage: under the holistic assumption in the whole world act, it is reasonable to presume that the same meaning is implied by the use of the same expression in every part of the act. Rule against surplusage (or redundancy): the proper interpretation of a statute is one in which every word has meaning. Nothing is redundant or meaningless. If different words had the same meaning, then the second word would be surplusage, or unnecessary. Belt and suspenders (counter to the rule against surplusage): They were duplicative on purpose . They intended to do this in order to get their point across Punctuation & Grammar Cannons: Oxford Comma: comma placement can be critical. Ex: red, green, yellow, and blue vs. red, green, yellow and blue. Punctuation Rules: The punctuation canon in America has assumed at least three forms: (1) adhering to the strict English rule that punctuation forms no part of the statute; (2) allowing punctuation as an aid in statutory construction; and (3) looking on the punctuation as a less than desirable, last-ditch alternative in statutory interpretation. Conjunctive vs. Disjunctive: The “And” vs “Or” Rule: DeMorgan’s Rules for conjunctions and disjunctions Not (A and B) means Not A or Not B Not (A or B) means Not A and Not B Mandatory vs Discretionary Language: The “May/Should” vs the “Shall/Must” Rule When a statue uses mandatory language, courts often interpret the statue to exclude discretion to take account of equitable or policy factors. On the other hand, ordinary usage does sometimes consider may and shall interchangeably. Singular vs Plural Numbers, Male and Female Pronouns: Both of these rules are not often followed The Golden Rule (Against Absurdity) - and the Nietzche Rule The golden rule is that interpreters should adhere to the ordinary meaning of the words used, and to the grammatical construction, unless that leads to any manifest absurdity or repugnance, in which case the language may be varied or modified, so as to avoid such inconvenience, but no further. Referential and Qualifying Words: The “Last Antecedent Rule” Referential and qualifying words or phrases refer only to the last antecedent, unless contrary to the apparent legislative intent derived from the sense of the entire enactment. The modifier would apply to all of the antecedents (Lockhart Pg. 612- whether minors/wards modified all or part). Cannons For choosing or avoiding ordinary meaning: Ambiguous: susceptible to more than one meaning and therefore it is open to looking outside of the text (purposivist, intentionalist, pragmatic) Lexical: “hard” Structural: Tibetan history teacher – Tibetan history/ teacher or Tibetan/ history teacher Absurdity rule: when words have one ordering meaning, but that ordinary meaning seems odd given the circumstances of the case. Allows judges to correct legislative policy mistakes and is thus compatible with intentionalism and purposivism. The absurdity doctrine says that if legislators had foreseen the problems raised by a specific statutory application, they could and would have revised the legislation to avoid such an absurd result. The absurdity and Holy Trinity was to avoid the result that would be contrary to legislative intent (using the ordinary meaning would lead to an absurd result). o Intentionalism: It is a familiar rule, that a thing may be within the letter of the statute and yet not within the statue, because now within its spirit, nor within the intention of its makers. – Holy Trinity Constitutional avoidance: if two reasonable or fair interpretations exist, one of which raises is a constitutional issue, the other interpretation should control. If the statue can be construed in more than one way and it raises a serious constitutional question then we must interpret it in the way that avoids the constitutional question. An act of Congress ought not to be construed to violate the constitution if any other possible construction is available. o We assume Congress clearly want everything to be constitutional Intrinsic Cannons: Title: Argue the purpose from the title. However, they are not controlling. Preambles, Purpose Clauses and legislative findings Provisos: Exceptions or provisos are clauses that create an exception or limit the effect of the general rule. Extrinsic Cannons: Legislative History and Purpose Context: social and historical, political, legal, and economic. Legislative history: can be used to shed light on the intent or purpose of the statute. The dog that did not bark (Sherlock Holmes Cannon): when Congress is silent. Policy-based Cannons: The rule of lenity: if two reasonable interpretations of a penal statute exists, the court should adopt the less penal interpretation (criminal statutes only). This is always the last argument for a narrow reading. Other Cannons: Elephant in the mouse hole: Congress ‘does not . . . hide elephants in mouseholes. Where an agency uses “vague terms and ancillary provisions” (the mousehole) to alter “the fundamental details of a regulatory scheme” (the elephant), the agency’s assertion of authority is forbidden. Avoid the greatest injustice Canons and Legal Reasoning Debunking Canons - Llewellyn’s Dueling Canons (Pg. 700) There are two opposing Canons to every point. Just because there are always counters does not mean they are useless. Context will tell you which is more persuasive - turns on context. Extrinsic Doctrines of Statutory Interpretation Common Law Use the Common Law to get the ordinary meaning. Rejected Proposals Rule Interpreters should be reluctant to read statutes broadly when a committee, chamber, or a conference committee rejected language explicitly encoding that broad policy. Other Statutes Statutory Interpretation is a holistic endeavor In pari materia rule: other statutes might use the same terminology or address the same issue as the statute being interpreted. Modeled or borrowed statute rule: another statute might have been the template from which the statute in issue was designed. Presumption against implied repeals: there might be a later statute possibly changing the implications of the statute being interpreted. The courts routinely assume that, unless there are strong indications to the contrary, the newer statute should be interpreted consistently with the older statutes upon which it was modeled. Context: Contextualism: the process of using the context to determine why a legislature acted in order to understand what the statute means. Social and Historical Context Political Context Legal Context Economic Context Legislative History: Legislative History: includes everything that was developed during a legislative process: committee reports, floor debates, conference committee reports, executive signings and veto statements, override memos, hearing transcripts, and even statements from sponsors. Most persuasive is the conference committee report o Will not overcome the text of the statute Justice Scalia believed that committee reports in particular are untrustworthy Using Legislative History: Generally, a judge uses legislative history to find a specific intent, they are looking to discover whether the legislature had a specific idea about a precise issue before the court. The argument for using Leg History is to confirm absurd meaning, to find the ordinary meaning of terms at the time enacted. o Constitutionally required that congress maintains a journal to be open and transparent. Criticizing Legislative History: The argument against using Leg History are that: o Constitutionality Issues: it is anti-democratic to the point of unconstitutional - not voted on by both houses and signed by the president. o Reliability Issues: practical concerns because it is unreliable Legislatures do not read every report or attend every event. Can contain conflicting issues Legislative history can be manipulated to support a result (cherry picking) - Ex: Weber When Congress Does Not Speak: Dog that did not bark canon Using Legislative History to find the Purpose: Knowing why a law was enacted can explain its purpose. Legislative Inaction A legislature's silence to an interpretation means agreement with that interpretation.