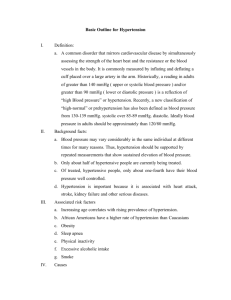

State Establishment “Dnipropetrovsk Medical Academy of Health Ministry of Ukraine” Department of Internal Medicine 1 SECONDARY HYPERTENSION HYPERTENSIVE CRISIS Associate Professor, Olha Cherkasova, M.D., Ph.D. Dnipro, 2020 • Hypertension is sustained elevation of resting systolic BP (≥ 140 mm Hg) and/or diastolic BP (≥ 90 mm Hg), based on the average of two or more seated BP readings during each of two or more outpatient visits. Definition • Secondary hypertension is defined as increased systemic blood pressure (BP) due to an identifiable cause. Only 5– 10% of patients suffering from arterial hypertension have a secondary form When to suspect secondary hypertension clinically (1) Absence of family history of hypertension Severe hypertension ˃180/110 mm Hg with onset at age <20 years or ˃ 50 years Difficult-to-treat or resistant hypertension with significant end-organ damage feature Presents with combination of pain (headache), palpation, pallor and perspiration – 4 P’sof phaeochromocytoma When to suspect secondary hypertension clinically (2) Polyuria, nocturia, proteinuria or hematuria – indicative of renal disease Persons with short or thick neck – Obstructive Sleep Apnoea Hypertension in children Significant elevation of plasma creatinine with use of ACE inhibitors Causes of secondary hypertension with clinical indications Common causes Renal parenchymal disease Renovascular disease Primary aldosteronism Obstructive sleep apnea Drug or alcohol induced Uncommon causes Pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma Cushing’s syndrome Hypothyroidism Hyperthyroidism Aortic coarctation (undiagnosed or repaired) Primary hyperparathyroidism Congenital adrenal hyperplasia Mineralocorticoid excess syndromes other than primary aldosteronism Acromegaly Renal Parenchymal Diseases CAUSES • glomerulonephritis, • diabetic nephropathy (diabetic kidney disease), • kidney damage in the course of systemic connective tissue diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, systemic vasculitis), • tubulointerstitial nephritis, • obstructive nephropathy, • polycystic kidney disease, large solitary kidney cysts (rare), postirradiation nephropathy, hypoplastic kidney, renal tuberculosis (rare). Renovascular Hypertension Patients groups • older arteriosclerotic patients who have a plaque obstructing the renal artery, frequently at its origin, • patients with fibromuscular dysplasia Patient with suspected atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis Primary Aldosteronism PA is defined as a group of disorders in which aldosterone production is inappropriately high for sodium status, relatively autonomous of the major regulators of secretion (angiotensin II, plasma potassium concentration), and nonsuppressible by sodium loading. Excess aldosterone, inappropriately high for the salt intake status, causes hypertension, cardiovascular and renal damage, sodium retention, suppression of plasma renin, and increased potassium excretion that (if prolonged and severe) may lead to hypokalemia. PA is commonly caused by an adrenal adenoma, unilateral or bilateral adrenal hyperplasia, or in rare cases adrenal carcinoma or inherited conditions of familial hyperaldosteronism . Patients with suspected primary aldosteronism Cushing's Syndrome Clinical Features • Symptoms associated with hypercortisolemia include weight gain, lethargy, weakness, menstrual irregularities, loss of libido, depression, hirsutism, acne, purplish skin striae, and hyperpigmentation. • The signs associated with Cushing's syndrome are extremely varied and differ in severity. Signs that differentiate Cushing's syndrome from pseudo-Cushingoid states most reliably include the presence of proximal myopathy, easy bruising, and thinness and fragility of the skin. Pheochromocytoma • Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas are tumors derived from chromaffin cells in the adrenal medulla or extra-adrenal paraganglia. Adrenal tumors and tumors located in the sympathetic paraganglia will be referred to as pheochromocytomas. Pheochromocytomas are found in 0.2-0.6% of subjects with hypertension. The cost-effectiveness of diagnostic workup of pheochromocytoma is markedly restricted by low specificity of clinical symptoms together with symptoms overlapping within a wide variety of other conditions, including idiopathic hypertension, hyperthyroidism, heart failure, migraines, and anxiety. • Hypertension occurs in about 80-90% of patients with pheochromocytoma. About half of these patients develop sustained hypertension, another 45% present with paroxysmal hypertension, while 5-15% are normotensive. • Several additional endocrine disorders, including thyroid diseases and acromegaly, cause hypertension. • Mild diastolic hypertension may be a consequence of hypothyroidism, whereas hyperthyroidism may result in systolic hypertension. • Hypercalcemia of any etiology, the most common being primary hyperparathyroidism, may result in hypertension. Obstructive sleep apnea • Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a disease caused by recurrent episodes of upper airway collapse (causing apnea) or upper airway narrowing (causing hypopnea – a marked decrease in airflow) at the level of the pharynx with normal function of the respiratory muscles. Apnea, hypopnea, or both cause episodes of nocturnal hypoxemia and arousals from sleep that lead to sleep fragmentation (patients are unaware of most of these episodes). Patients with suspected obstructive sleep apnoea Coarctation of the aorta • Coarctation of the aorta refers to a narrowing of the aorta, most frequently at the level of the aortic isthmus, ie, distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery, opposite to the ligamentum arteriosum. CLINICAL FEATURES 1. Symptoms usually develop in the second or third decade of life and are associated with prestenotic hypertension in the aorta. They include headaches, epistaxis, and disturbances of vision. 2. Signs involve hypertension (blood pressures measured on the upper extremities are >10 mm Hg higher than those measured on the popliteal artery); different blood pressures on both brachial arteries in patients with stenosis including the origin of the left subclavian artery; weak or absent pulse on the femoral arteries; and rarely, intermittent claudication (usually collateral circulation is well developed). Drug-related hypertension • NSAIDs • glucocorticoids • diet pills (i.e. phenylpropanolamine and sibutramine), stimulants (i.e. amphetamines and cocaine), • decongestants (i.e. phenylephrine hydrochloride and naphazoline hydrochloride); • cocaine • licorice • Oral contraceptives (oestrogen + progestin) Drug-related hypertension (2) • Antidepressant agents (i.e. venlaflaxine and monoamine oxidase inhibitors) • Immunosuppressive agents, particularly cyclosporine A, • Inhibitors of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGFi) (i.e. bevacizumab, Avastin®) or tyrosine kinase inhibitors (i.e. sunitinib, Sutent®, sorafenib, Nexavar®) Hypertensive crisis • Hypertensive crisis (acute severe hypertension): an acute severe increase in systolic blood pressure ≥ 180 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 120 mm Hg with a high risk of complications. • The two categories of hypertensive crises are: urgent and emergency. Hypertensive Urgency • Hypertensive crisis that is either asymptomatic or with isolated nonspecific symptoms (e.g., headache, dizziness, or epistaxis) without signs of organ damage • Blood pressure can be brought down safely within a few hours with blood pressure medication Hypertensive emergency • hypertensive crisis with signs of end-organ damage, mainly in the cardiovascular, central nervous, and renal systems • Blood pressure must be reduced immediately to prevent imminent organ damage. This is done in an intensive care unit of a hospital. Organ damage associated with hypertensive emergency may include • • • • • • • • Changes in mental status, such as confusion Bleeding into the brain (stroke) Heart failure Chest pain (unstable angina) Fluid in the lungs (pulmonary edema) Heart attack Aneurysm (aortic dissection) Eclampsia (occurs during pregnancy) Signs and symptoms of end-organ dysfunction (1) Cardiac • Heart failure exacerbation, pulmonary edema: dyspnea, crackles on examination • Myocardial infarction: chest pain, diaphoresis • Aortic dissection: chest pain, asymmetric pulses Neurologic • Hypertensive encephalopathy: headache, vomiting, confusion, seizure, blurry vision, papilledema • Ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke: focal neurological deficits, altered mental status Signs and symptoms of end-organ dysfunction (2) Renal • Acute renal failure: azotemia and/or oliguria, edema Ophthalmic • Acute hypertensive retinopathy: blurry vision, decrease in visual acuity, retinal flame hemorrhages, papilledema Other • Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia: fatigue, pallor Additional clinical features that may be present • Signs of sympathomimetic drug toxicity • In pregnant patients (in the second or third trimester ): signs of pre-eclampsia or eclampsia • Signs of catecholamine-secreting tumors Approach to management (1) 1. Confirm blood pressure manually and on bilateral upper extremities. 2. Determine if there are signs of end-organ damage. • Focused history/physical • Select screening tests 3. For hypertensive emergencies • ABCDE approach • Admit patients (ideally to ICU). • Lower the blood pressure acutely using IV agents and aim for targets based on the affected end-organs • Evaluate and treat underlying disorders. Approach to management (2) For hypertensive urgency • Select, reinstitute, or modify oral antihypertensive therapy. • In patients with a new diagnosis, evaluate for secondary causes of hypertension. • Arrange follow-up, monitoring, and counseling. Red flags for hypertensive crisis • Dyspnea • Chest pain • Altered mental status • Focal neurologic symptoms Treatment Hypertensive urgency (1) • Outpatient treatment is recommended. • Move patient to a quiet room for 30 minutes. • Reinstitute or increase the dosage of existing oral antihypertensive therapy. • For patients with nonspecific symptoms that do not constitute endorgan damage (e.g., isolated headache, nonspecific dizziness, and epistaxis), consider a rapid-acting oral antihypertensive agent prior to discharge. • Clonidine • Captopril • Labetalol • Prazosin Treatment Hypertensive urgency (2) • Monitor the patient for a few hours to ensure BP is improving. • For patients with a first diagnosis of hypertension, consider evaluation for secondary hypertension. • Discharge and follow-up • Ensure close follow-up with an outpatient provider. • Long-term treatment goals: See “Treatment” of hypertension. • Sodium restriction diet • Hypertensive urgency is usually caused by nonadherence to antihypertensive therapy. Aggressive intravenous antihypertensive therapy is not reiqured. Hypertensive emergency General principles • ICU admission and immediate initiation of intravenous antihypertensive therapy (see table below) • Continuous cardiac monitoring • Consider intra-arterial blood pressure monitoring. • Identify and treat any contributing comorbidities (e.g., chronic renal failure). • IV fluids if signs of volume depletion • Monitor BMP every 6 hours. Hypertensive emergency Rate and target of blood pressure reduction General goal • Reduce BP by max. 25% within the first hour to prevent coronary insufficiency and to ensure adequate cerebral perfusion pressure. • Reduce BP to ∼ 160/100–110 mm Hg over the next 2–6 hours. • Reduce BP to patients baseline over 24–48 hours. Intravenous antihypertensives Calcium channel blockers • Nicardipine Nitric-oxide dependent vasodilators • Sodium nitroprusside • Nitroglycerin Direct arterial vasodilators: hydralazine Antiadrenergic drugs Selective beta-1 antagonist: esmolol Nonselective beta blocker with alpha-1 antagonism: labetalol Nonselective alpha antagonist: phentolamine ACE inhibitor: enalaprilat