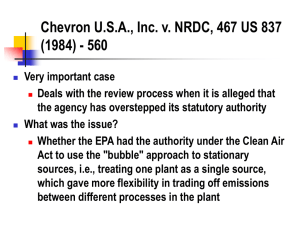

Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 INTRODUCTION & POLICY - - - What is an agency? o Term agency excludes: Legislative, Judicial, or Executive Office. o Congress has no express provisions authorizing agencies. HOWEVER, some clauses imply a federal bureaucracy. Congress has broad authority to “create” governmental “offices” and to structure officers “as it chooses.” BUT cannot touch on President’s constitutional authority. Buckley The Appointments Clause: The President may appoint “Officers” with Senate advice and consent and “Heads of Departments” can possibly also make appointments. Art. II § 2, cl. 2. Opinions in Writing: The President “may require the Opinion, in writing, of the principal Officer in each of the executive Departments, upon any Subject relating to the Duties of their respective Offices.” Art. II, § 2, cl. 1. Take Care Clause: the President “shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” Art. II § 3. o How are agencies created? By statute, an “organic act.” Organic act gives them power to act in certain ways. o Policies underlying Separation of Powers: Helps promote uniformity and impartiality in the application of sanctions. Reduces the power that government can exert against citizens. Reduces the possibility that nay one faction can takeover government. Reserves a special role for an independent judiciary; compliance with applicable law. Legislative Controls (over agency action): o Power of the purse: cut off funding (“No funds can be used for XXX” can only be revived with new appropriation). o Write narrow / specific legislation (this doesn’t always work and doesn’t help you with regulations already passed). o Require congressional approval before certain regulations have effect. (REINS Act— congressional approval required for regulations with over $100 million in effect, would relegate agencies to just “recommenders,” would be very time consuming for Congress). machete o Suspend agency regulation and only allow the proposal of legislation o Congressional Review Act (CRA), permits Congress to repeal regulations within 6o legislative days through a joint resolution of disapproval. Reviewing regulations after the fact, responding to fire alarms but not engaging in police patrols. (Only 1 regulation has been disapproved under this act!) scalpel o Opposite of the CRA, Congress could require approval by joint resolution before regulations go into effect. o Oversight hearings o Sunset Clauses o Insert legislative history (i.e. that dictates scope of regulation/agency action) agencies take LH seriously, when committee issues a report it is important even if courts don’t always take it seriously. o Legislative veto (invalidated in Chadha) o Line-item veto act (invalidated in Clinton) What problems call for regulation? o Spillover & Externalities, ex: smokestacks 1 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 Collective Action Problems—things that are in every person’s interest but there is not enough of an incentive to group together to get to the most efficient outcome. o Inadequate Information—information asymmetries, ex: drug health & safety regulation. o Natural Monopolies—some kinds of enterprises where it will naturally end up in a monopoly and thus we must do something about it. o Other reasons for regulating? Economic: rent control, allocating scare goods based on who could use it best, preventing excessive competition; noneconomic: redistributing wealth, paternalism of government. Regulatory tools: o Price controls, screening or licensing, standards, fees, taxes, grants and subsidies, provision of information, cooperation. Theories of Agency Behavior: o 1787: Madison—suspicion of government power o 1875-87: ICC (first big industry agency) regulatory agency established by Interstate Commerce Act, original purpose was to regulate railroads. Nonpartisan agency with impartial expertise, Congress had to be careful to craft the right structure for technocrats with expertise to implement the rules. Not a big role for the courts. o 1932: New Deal—government wanted to correct “market imperfections,” administrated needed all the authority, no judicial review, no congressional oversight. Post-depression, new administration said it is time to take action, laissez faire capitalism doesn’t work, thus need agencies to regulate. James Landis—key new deal-er, “The Administrative Process” Said separation of power was inadequate to deal with modern problems. View was inapposite to Madison, believed that gov. needed to be able to move quickly. *1936-1976: NOT a single congressional enactment invalidated on separation of powers grounds. Landis’s view was widely held (but today no one uses Landis’s language!). Functionalist view: let’s just make sure we have a functioning democracy. Formalist: Madisonian view, checking powers between branches. o 1946: APA / Capture — agencies have a life cycle, would be captured by industry/unduly influenced and would become an advocate for that industry instead of for the public. Agencies have an interest in industry continuing, want to ensure its existence (symbiotic relationship between agency & industry). o 1962-80: fear of capture becomes very great, agencies are working to help companies they are regulating, screwing up competitive world, this leads to aggressive judicial review, detailed statutes. o 1980s-today: president control, public choice theory, use of cost benefit analysis. Public choice theory: applying economics to political world, everyone actually acts in a self-interested manner, not in manner of public interest. (Hardcore version of this is that it wouldn’t matter who was elected, industries would prevail. BUT obviously this is not the case, different laws get passed with different representatives, public interest plays some role.) o - - THE CONSTITUTIONAL POSITION OF ADMINISTRATIVE AGENCY & NONDELEGATION - Are there things that are explicitly legislative powers? (i.e. cannot be delegated) o Everyone agrees that Congress can make laws and leave implementation to agencies. o When does “mere implementation” cross the line into lawmaking? (KEY question) How much discretion is allowed to be decided on by agencies? 2 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o Visions of ower: 1) no overlap between J, E, L; 2) a little overlap; 3) a lot of overlap; 4) all in the mix. No one really adopts the first position (even Madison), EVERYBODY agrees there is some overlap. Nondelegation doctrine - Art. I, § 1 Const.: “all legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States.” o Intelligible Principle – When Congress does confer decision making authority to agencies, it must lay down “by legislative act an intelligible principle to which the person or body authorizes to act is directed to conform.” Analysis of Non-Delegation Challenge: Nondelegation inquiries begin with interpreting the statute to see if Congress provided an intelligible guiding principle. o 3 positions: 1) vesting legislative powers in Congress is an initial and final allocation, power cannot be transferred; 2) when Congress enacts a statute granting authority to executive the statute is a delegation of legislative power if the scope of the grant is too broad/vests too much discretion; 3) when Congress enacts a statute granting authority to the executive, there is no “delegation” of legislative power, Congress has exercised it by enacting the relevant statute. o ALA Schecter Poultry Corp. v. United States (Slaughterhouse Case)(1935): Facts: Petitioners convicted for violations of Live Poultry Code, contend that code adopted pursuant to an unconstitutional delegation by Congress of legislative power. The National Industrial Recovery Act authorized the President of the United States to approve "codes of fair competition" for a trade or industry. Code promulgated under National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), administered through an “industry advisory committee” (private group). Holding: Congress may not delegate legislative power to the executive branch to exercise unlimited lawmaking discretion to promote trade or industry. Congress must outline specific standards for how the president must exercise that power. No limiting authority in NIRA. Court strikes down statute, too much power is given to president (and then delegated to private groups). o Worried about no political accountability for private groups and aggrandizement of presidential power. o Benzene Case (1980): Facts: Industry challenged regulatory standard limiting occupational exposure to benzene. Under OSHA, Dept. of Labor responsible for developing standards, Act delegates broad authority to secretary. §3(8): standards created by secretary must be “reasonably necessary or appropriate to provide safe or healthful employment.” §6(5): secretary must “set the standard which most adequately assures to the extent feasible, on the basis of best available evidence, that no employee will suffer material impairment of health or functional capacity.” 3 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o o o Where toxic material is carcinogen, secretary took position that no safe level of exposure exists, must set limit at lowest technologically feasible level (= “to extent feasible”) that will not impair viability of industry. Benzene set at 1 PPM, but no evidence that Benzene harms under 25 ppm. Holding: standard unenforceable because it was not supported by appropriate findings. Authorizing statute required OSHA to demonstrate a significant risk of harm in order to justify setting an exposure level (organic statute gives this intelligible principle). o Unreasonable to assume that Congress intended to grant so much unbridled authority to Secretary, such a delegation would be unconstitutional. o *Congress drew the line in the Benzene case of how much power congress could delegate. If a statute has two meanings, choose the one that avoids constitutional question (avoid nondelegation issues). American Trucking Associations v. EPA (D.C. Cir. 2001): Facts: Clean Air Act requires EPA to set standards for national ambient air quality standards for air pollutant at a level requisite to protect public welfare. For each pollutant, the EPA set a primary standard to protect public health “with an adequate margin of safety,” and a secondary standard to protect the public welfare. In 1997, the EPA issued rules revising the NAAQS for particulate matter (PM) and ozone. The rules indicated that any amount of PM or ozone posed a possibility of some health risk. The rules revised the ozone NAAQS from 0.09 to 0.08 but did not explain how the new level was set or how it worked. Holding: Court says “requisite” could mean anything, EPA has not drawn enough lines and there is no intelligible principle set out by Congress in the statute (delegating power). Does not strike down statute, sends back to agency to let them create a determinate standard. Wants agency to be able to promulgate rules. Whitman v. American Trucking Associations (S. Ct. 2001) Facts: Clean Air Act (CAA) requires the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (defendant) to promulgate National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) for certain air pollutants. Section 109(b)(1) of the CAA directs the EPA to set ambient air quality standards, the attainment and maintenance of which in the judgment of the Administrator are necessary to protect the public health. In July 1997, the Administrator revised the NAAQS for particulate matter and ozone. Reasoning: Court flatly rejects idea that statute had no intelligible principle. Scope of discretion in statute is within the outer limits of nondelegation precedent (court has only found two statutes ever to lack an intelligible principle—one which provided literally no guidance and one which conferred authority to regulate entire economy). Degree of agency discretion that is acceptable varies according to scope of the power congressionally conferred. Court said requisite = no more and no less than necessary. Holding: reverse Court of Appeals, remand for reinterpretation that would avoid supposed delegation of legislative power. Gundy v. United States (supplement) Holding: Authorizing the attorney general to enforce the national Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act against pre-act offenders does not violate the nondelegation doctrine under the current intelligible-principle standard. 4 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 THE EXECUTIVE AND THE AGENCIES Legislative Veto - Immigration & Naturalization Service v. Chadha (1983): *foundational case o Facts: Chadha visa expired, ordered deported, Attorney General suspended deportation. Immigration & Nationality Act §244 allows Senate or House to veto AG’s decision within a specific period of time. issue is whether action of ONE House of Congress would violate strictures of Constitution. Art. I vests power in Congress consisting of Senate AND House, every bill that passes through House and Senate shall before becoming a law be presented to president. Bicameral system ensures that legislation should not be enacted unless it is carefully considered by Nation’s elected officials. Congress made deliberate choice to delegate to AG in Exec. branch authority to allow deportable aliens to remain in country. Disagreeing with AG’s decision involves determination of policy that Congress can only implement the traditional way—bicameral passage followed by presentment to president. Only 4 provisions in constitution that allow for one house to act alone (impeachment and trials, ratifying treaties, presidential appointments) o Holding: action by house was not within any express constitutional exception authorizing one house to act alone, action thus subject to standards prescribed in Art. I, need bicameral presentment (formalist opinion). o Dissent: Congress is just reserving some power that it delegated, otherwise it is giving a lot of power to agency. Appointments Clause: - Art. II § 2, Cl. 2—Empowers President of the United States to appoint certain public officials with the “advice and consent” of the U.S. Senate. o Not Covered by clause: Non-Officers (ak amere employees) (Congress can do whatever it wants in deciding how these people are hired). o Officers: Principal officers: president nominates, senate confirms Inferior officers: if Congress so legislates, inferior officers can be appointed by president, or courts of law, or heads of department. *Appointments clause includes all persons who can be said to hold an office under the government, any appointee exercising significant authority pursuant to the laws of the US. An “office” has 2 features: 1) involves a position to which is delegated by legal authority a portion of the sovereign powers of the federal government 2) must be “continuing” (cannot be one-shot position like a gov. contractor) o Control - Most obvious tool by which president can assert control over agencies is hiring and firing officers. o Political appointees have increased in recent decades, premium placed on loyalty and ideological affinity. o Note: these days Congress errs on the side of having everyone Senate confirmed. This results in us not knowing exactly whose position demands senate confirmation. Thus the fact that you are senate confirmed does NOT mean automatically that you are a superior officer. o Buckley v. Valeo (1976) 5 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o o Facts: Federal Election Campaign Act created Federal Election Commission (FEC) agency authorized to write rules, investigate violations, hold hearings, commence civil judicial enforcement actions. FEC had 6 members, president appointed 2 by confirmation by senate AND house, speaker of houses and president of senate each appointed 2, subject to confirmation by both houses, secretary of senate and clerk of house were ex officio members without votes. Issue: what is the line between officers and employees? Holding: appointments of FEC violated appointments clause. Selection process does not align with Art. II process with respect to 4/6 members because neither the president nor head of any department nor judiciary has any voice in selection. House is playing a role and house should not have a role in appointing officers, these people have “significant authority” in holding civil enforcement actions, so must be officers not employees. Power to investigate that is confided in Commission falls into the same general category as those powers which Congress might delegate to one of its own committees Morrison v. Olson (1988): (inferior officers case) Congress can place the appointment of “inferior officers” in the president alone. Facts: Title VI of the Act permitted a court called the Special Division to appoint an independent counsel to investigate and prosecute certain high-ranking government officials for violations of federal criminal laws upon request by the Attorney General. The independent counsel could terminate the position when the investigation and/or prosecution was complete. Additionally, the Act gave the Attorney General sole removal power of an independent counsel “for good cause.” Holding¨independent counsel was an inferior officer and so appointment by a court without Senate confirmation was permissible. Court focuses on 4 factors to find that independent counsel was an inferior officer: Appellant is subject to removal by higher executive branch official. Appellant is empowered by the Act to perform only certain, limited duties…restricted to investigation and if appropriate prosecution. Appellant’s office is limited in jurisdiction…restricted to certain federal officials suspected of certain serious federal crimes. Appellant’s office is limited in tenure. Dissent (Scalia): many indisputably principal officers such as heads of departments are subject to removal by a higher official, appellant is not subordinate to another officer and an inferior officer needs to have a superior. Significant Authority Edmond v. United States (1977): (*Scalia opinion) Facts: Coast Guard Court of Criminal Appeals hears appeals from decisions of court-martials, decisions are subject to review by US Court of Appeals for Armed Forces. Judges appointed by secretary of transportation without advice and consent of senate. Claims that Morrison did not set forth a definitive test for whether an officer is “inferior” under the Appointments Clause. Exercise of significant authority marks line between officer and non-officers NOT officer and inferior officer. 6 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o o o Whether one is inferior depends on whether he has a superior, must be supervised at some level by others who were appointed by President. Holding: Court of Criminal Appeals has no power to render a final decision on behalf of the US, every decision is reviewed. Thus, judges were inferior officers by reason of this supervision. Lucia v. SEC (supplement) Holding: Significant Authority = initial determinations, even if overridable by agency head. Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board “Peakaboo” Case (2010) Facts: Sarbanes Oxley Act created PCAOB, 5 members appointed by SEC and removable by SEC at will. Board members are inferior officers whose appointment congress may permissibly vest in a head of department, doesn’t matter that SEC is composed of a multi-member body (as opposed to a singular person). SEC is still a freestanding component of Exec. Branch which constitutes a “department” for appointment clause purposes. Holding: upheld provision of act regarding appointments of Board members. Court notes superior-inferior rule, cites Edmond (replaces Morrison as case on appointments issue). BUT remember though it is necessary to have a superior (if no superior, then principal officer), it is not necessarily sufficient. *If you have a superior are you necessarily an inferior? We don’t know! Think of the solicitor general has superior AG, but we consider the solicitor general to wield a lot of power. Multilevel good cause protection is impermissible under Art. II. (Commission has power to appoint and remove so cannot restrict this). Freytag Holding: work must be reviewable / supervised by someone who was nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate What if agency loses all Principal Officers? US v. Eaton Holding: Agency can function for a limited period of time without principals under certain conditions Vacancies Reform Act Recess Appointments - - Note: if an agency is headed by someone who needs Senate confirmation and that person is not confirmed, departments cannot function, need principal officer to make decisions for these agencies. Could effectively shut down an agency by never appointing a principal officer and never getting Senate confirmation. Senate is not always available to perform function of confirmation, when it is on recess, president can make temporary appointments (people can at least serve until next session). Noel Canning Case (supplement): o District court says there is only one recess and can only appoint if vacancy arises during that recess. o Supreme Court says no, notes that every past President has made recess appointments that did not meet these qualifications. Can appoint during a recess, BUT senate is in session whenever it says it is (Senate thus can always claim this). If Senate does say it is in session then a “vacancy” appointment would be unconstitutional. 7 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 Removal - - - - Constitution directly addresses the appointment of federal officers, silent as to their removal. Removal power more important than appointment—can get rid of someone who turns against you! 4 possible ways to remove: o Same way they came in (Senate appointment & senate removal as well) o Take Care - President takes care that law is faithfully executed, thus president must have people that ensure this ability (if they don’t, can remove). Basically, at will removal by the President o Removal by impeachment (Constitution) o Congress has complete power to set rules for removal. Congress legislating removal The Decision of 1789: o pro president position, president gets to remove! President has long seized on this decision, Congress supported this. Removal By President o Myers v. United States (1926): (option 2, opinion written by Justice Taft, former president) Facts: Myers appointed postmaster under statute stating that postmaster “shall be appointed and may be removed by the President by and with the advice and consent of Senate.” Pres. Wilson removed Myers, claimed statute was unconstitutional because it limited president’s power to remove an exec. branch official who the president could find negligent and inefficient. Holding: power to remove subordinates is inherently part of the executive power, Art. II §1 invests in president. Limitations on President o Humphrey’s Executor v. United States (1935): (option 4) FTC created to enforce antitrust law, President Hoover appointed Humphrey, President Roosevelt wanted to get rid of him and put someone else in his place who as more aligned with Roosevelt’s view. Provisions of Act allow for removal only for “inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.” Court distinguishes Myers, office of postmaster is unlike office involved now because postmaster is subordinate to president only, no legislative or judicial power. FTC effects legislative policies—fundamental necessity of keeping 3 branches of gov. separate from control of others. Holding: cannot remove a member of FTC commission except for 3 reasons given. Power of president to remove an officer depends on character of office—can remove purely executive officers, but not those who exercise judicial or legislative powers (like FTC here). President has the authority to remove executive officers but not those performing quasi-judicial powers o Morrison v. Olson (1988) (again) Ethics in Gov. act creates independent counsel post, AG would decide whether there were sufficient grounds to warrant an investigation of an official and need to refer matters to “special division” of 3 federal judges appointed by Chief Justice who would then name independent counsel. Independent counsel could be removed by AG for “good cause, physical disability, mental incapacity.” removal provisions make it analogous to Humphrey’s. Issue = whether removal restrictions impede President’s ability to perform constitutional duty. 8 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o o Holding: not really, cannot say “good cause” standard trammels on exec. authority, cannot see how president’s need to control the exercise of that discretion is so central to the functioning of Exec. branch as to require as a mater of constitutional law that the counsel be terminable at will by the president. Exec. through AG retains authority to terminate for “misconduct.” Court has not revisited this holding because Congress let Ethics in Government Act expire. Dissent (Scalia): Art. II §1, cl. 1 vests ALL executive power in president. This decision is flat out taking power away form president, doesn’t matter if you are not giving it someone else. Takes “unitary executive” position, meaning president can fire because every subordinate is under you. “Peakaboo” Case (2010) (again): *narrow holding (about double layer protection from removal) Issue = whether separate layers of protection may be combined—may the president be restricted in his ability to remove a principal officer, who is in turn restricted in his ability to remove an inferior officer, even though that inferior officer determines the policy and enforces the laws of the United States. Because of restrictions on president’s ability to remove commission members, president cannot hold commission fully accountable for board’s conduct contrary to Art. II vesting of exec. power in president. Holding: two levels of protection from removal for those who nonetheless exercise significant executive power, limits presidential authority—cannot be done. Dissent (Breyer): “For cause” restriction will not restrict presidential power significantly. Cong. and pres. had good reasons to enact this provision, insulate technical experts from political influence. Also, no statute that actually gives SEC commissioners for cause protection (everyone in the case just agreed on this and no one disagreed, so court just assumed). Seila Law v. CFPB Facts: CFPB structure was different from any agency in existence. It had a single director who was appointed by the president with the advice and consent of the Senate. That director served for a five-year period and could only be removed by the president for cause. Additionally, it was funded directly by the Federal Reserve rather than by appropriations from Congress. The CFPB issued Seila Law (defendant) an investigative demand to produce evidence related to possible illegal business practices. Seila Law refused, claiming that the CFPB did not have the authority to issue orders because its structure violated the separation-of-powers doctrine under the Constitution. Holding: President has the power to remove Officers who perform executive functions Exception: o Multimember, bipartisan commissions who do not perform executive functions (Humphrey Executor) Note: Interesting because most multimember bipartisan agencies perform executive functions, like enforcement, but the court still regards them as falling under the exception (Kagan Dissent) 9 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 - - - - - o Inferior Officers (Morrison) o Post-Seila Law – Congress is limited in preventing the President’s removal power Independent v. executive agencies o No definitive list or clear line of demarcation. Look to how heads of departments are chosen. o Most common thing that people look to: Are agency heads protected for “removal for cause?” If protected then independent! Executive can be removed at will (part of exec. branch) If not purely exec. then Cong. can put in the “for cause” requirements. o President’s influence is significantly greater over the executive than independent agencies. President can often determine who will run an independent agency. o President also controls budget requests, retains some control over selection of certain agency personnel, influences agency policy through introduction of substantive legislation. o Independent agencies: general characteristics “Headless fourth branch of government” Tend to be multimember boards (representatives from both parties) (president can pick chair), separate parties, set term lengths, staggered, removal ONLY for cause by president. FCC v. Fox o Holding: Independent agencies are not sheltered from politics but they are sheltered from the President and Presidential oversight. Bowsher v. Synar (1986) o Comptroller general appointed by president, subject to Senate confirmation. 16 year term, removal only for cause by a joint resolution of Congress. o Direct congressional role in removal of officers is inconsistent with separation of powers. Congress cannot reserve for itself the power of removal of an officer, gives Congress influence over Comptroller’s actions. o Holding: powers assigned to Comptroller are executive in nature (calculating budget estimates), Congress thus cannot have a role in the removal of the comptroller without intruding into executive function. Most that Congress could do would be to limit the president in allowing to fire for cause, but this limit is too powerful for Cong. to grant to itself. o *As a member of the house, no role in appointment of ANY officer. Role in removal? Impeachment proceedings (but this is v. cumbersome—never happened for any agency official) House has no other role! Cannot delegate exec. powers to itself (execution of laws), violates separation of powers! If Congress wants to create a new independent agency and wants to maintain removal power, can only delegate legislative powers like investigations (Buckley & FEC). Cannot give exec. powers if you are going to retain ability to remove under Bowsher. Default Removal Post-Seila and Bowsher: o The President has the Constitutional authority, no withstanding legislation, to remove any principal officer and some inferior officers. o There are protections for Principals of multimember bipartisan agencies. o Congress can have no role in the removal of anyone exercising executive authority. From Congress’ POV, this is a disaster, they now have no control in this space. What can the president do as a matter of control? o Presidential memos: written in form of requests (“should” do this, “I request”), no orders, just suggestions. In reality though, no agency head is going to refuse presidential suggestions. This happens less with independent agencies because there is not the same ability to fire. o Executive orders: demonstrate how they are going to exert control over agencies. 10 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o o OIRA: (Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs) all significant ($) regulations go through here, the funnel. Review of what agencies do, began in Regan era (Clinton continued), cost-benefit analysis of all regulations, benefits must outweigh costs. Headed by administrator appointed by president with advice & consent of senate. Staff consists of about 50 professionals. OIRA can propose regulations, prompt letters to agencies suggesting cost effective regulation. Takes all meetings requested, but head of OIRA doesn’t have to be at all meetings. OIRA reviews take a while—1 year +, puts serious time constraints on agencies. Criticisms: Focus too much on costs Slow things down Violation of separate of powers? OIRA driving cost benefit analysis no matter what Cong. sets out, more power going to exec. branch. *None of this applies squarely to independent agencies. AGENCY STRUCTURE & ADMINISTRATIVE DISCRETION, SUBSTANCE, AND REGULATORY PERFORMANCE - - Functions and bias at agency head level o Withrow v. Larkin (1975) L practiced medicine, board investigated him and held a hearing, sued saying it was unfair and unconstitutional to have investigator make final decision. Issue = whether it is unconstitutional to have a party who investigates also have a role in deciding the outcome of the hearing or adjudication process. (DPC challenge) Holding: district court erred in entering restraining order against the Board’s contested hearing and granting a preliminary injunction (hearing should have been able to proceed). Case law rejects the idea that combination of judging and investigating function is a denial of due process. (judges do this all the time with issuing arrest warrants and then judging a trial) o Gibson v. Berryhill (1973) AL Board of Optometry, brought proceedings against Lee Optical. Board acted as prosecutor and judge. Lee did a lot of business in AL, if forced to suspend operations, members of board of optometry would profit. clear personal benefit Holding: affirm district court which found that this bias unconstitutionally disqualified the board from hearing the charges filed against Lee. Those with substantial pecuniary interest in legal proceedings should not adjudicate these disputes. Administrative Judges v. Administrative Law Judges (2 separate things!) o AJ Less of indicia of independence than ALJ Lower pay, less job security Selection by agency themselves Depend a lot on agency regulations Hired the way anyone else at agency is hired Informal adjudications *Vast majority of administrative officials are AJs compared to ALJs o ALJ A lot of separation between ALJ and agency, not housed with agency 11 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 - - See themselves with adjudicative powers (APA § 554(d)) Only required for formal adjudications (with magic words to trigger) Preside over (rare) formal rulemakings as well (i.e. ALJ drafts peanut butter rule, then it goes to agency head who probably redrafts it). Cannot consult anyone on fact/issue when making decisions Not subject to supervision by anyone with professional function Proceedings look like Art. III judicial proceedings Selection by office of personnel (not agency) Still agency employee but removed from agency control *Not judges in constitutional sense, but perform many judge-like functions administer oaths, issue subpoenas, rule on offers of proof… Agency thus combines prosecutorial and adjudicate functions, but different personnel in the agency generally must perform these functions. o After any ruling (by AJ or ALJ) can bring ruling to head of agency, head of agency can then reject decision! o Why do we allow for agency review of judge decisions? If decision were final then would be subject to provisions of Art. III judges. Have no superior so then would be a principal officer. Principal officers must be hired by president, ALJs are not. This is why agency head must have last word (otherwise appointment of ALJs would be unconstitutional)! Only agency head can do this because appointed by President and approved by Senate. Regulatory Performance o Safety based regulations Can create/increase risk: People have behavioral responses that offset intended benefit (ex: light cigarettes, airbags & reduction of seat belt use) Act of complying may pose risk—asbestos in building, someone has to remove it Cost of compliance with regulation, may have negative impacts on society, wealthier are healthier (less $ to take care of yourself) *Note: there are always tradeoffs to gov. regulation! o Why regulate at all? Information asymmetry—need information disclosure Paternalistic element—protect the people, even with full disclosure we’re not going to let you choose it, think people will make bad choices (cognitive bias). Bargaining power—who will expose themselves to various harms? Externalities—serious argument for regulation, control harm to others, ex: whose life should your car save? Cost/benefits—there is always a cost—how should we factor this in? What cost and what benefits should be considered? Value of equality? Alternative Remedies for Regulatory Failure o Deregulation: leave it common law and free marketplace to determine price, range of services. Might not work as a solution for externalities, need collectively managed controls. Non-commodity values might be inadequately reflected in market outcomes (people make different choices as individuals than they do as consumers). o Mismatch: fix mismatch between objective of regulatory program and tools used to achieve that objective. 12 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 - Pick tool that will interfere the least with private marketplace and which will rely to the maximum feasible extent on incentives, rather than administrative rules, to cure problem at hand. o Economic incentives: paying a fee for doing harm. Ex: cap and trade programs, moving away from command & control. o Default rules: in Britain, the “nudge office”—opt in v. opt out rules, comes up a lot with retirement accounts. The default does a lot of work, most people don’t change from default. o Sunset legislation: putting a time limit on agencies, need to re-up and decide all over again, but makes it harder to implement new regulations (definitely more time consuming). o Transparency: freedom of information act, government in the sunshine act of 1976—required open meetings, led to inefficiency because no one wanted to have open meetings so ended up everyone’s staff would talk and meet instead of formal agency heads meeting. o Disclosure and simplification: provide members of the public with relevant information at the right moment, usually when a decision is made. Generic Proposals for Regulation Reform o Cost-benefit analysis: emergence of cost-benefit as a response to economic, democratic, cognitive concerns. Objections: whole framework is wrong, the only things you can measure are things people don’t actually care about, can’t measure important things. Concerns about methodology, i.e. calculating value of life. People do a bad job estimating small risks and what its worth to them. Most often costs overestimated and benefits are a wide range, i.e. saving between 0 and 112 lives. Analysis of costs and benefits often depends on value judgments (same analysis done by two different people could turn out differently). PROCEDURAL REQUIREMENTS: RULEMAKING & ADJUDICATION Rulemaking v. Adjudication - - Londoner v. Denver (1908): o Ps, owner of property, challenged assessment of tax against them to cover costs for street paving. Colorado statute provided that Board of Public Works, after notice & opportunity for hearing, could order paving of a street on petition of majority owners. City council then had to approve and implement, assess costs. o Ps had filed written objectives, city council approved assessment without further opportunity for hearing. o Issue = whether council’s approval of assessments without opportunity for an oral hearing was constitutional. o Holding: something more than opportunity to submit writing is required for due process! Hearing denied to Ps in error, DP of law requires at some stage of proceedings taxpayer shall have opportunity to be heard. Bi-metallic Investment Co. v. State Board of Equalization (1915): o Suit to enjoin State Board from putting in force an order increasing the valuation of all taxable property in Denver. o P is owner of real estate, claims had no opportunity to be heard, therefore property will be taken without due process. o Holding: suit dismissed. Where a rule of conduct applies to more than a few people it is impracticable that everyone should have a direct voice in its adoption. 13 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 - - - *Distinguishes Londoner, that was a case where SMALL number of people were concerned and they were exceptionally affected. TAKEAWAY: Londoner and Bi-metallic cases—when agencies behave like legislature, constitution does not require procedural formality, no due process constraints (and no constitutional right to a hearing). o BUT when agency adjudicates, slightly different than an Art. II court—does not call for ALL procedural requirements that we would expect in a court, usually procedural constraints but not necessarily guaranteed all bells and whistles of a trial. o Generally adjudicative actions must be subject to a hearing, where people can bring their case, versus legislative actions are not subject to such a requirement. o Minnesota Board for Community Colleges v. Knight (1984): O’Connor says: “the Constitution does not grant to members of the public generally a right to be heard by public bodies making decisions of policy.” How do you distinguish between rulemaking and adjudication? o Generality More general rulemaking, legislative Specific adjudication o Prospectivity Forward looking rulemaking Retrospective adjudication o *Generality is more INFLUENTIAL factor. APA: 1946, most important statute in admin. law, but ORGANIC ACT controls if there is disagreement between the two! o Other sources of agency law: EOs, constitution, agency’s own regulations. APA is the default, ends up being left in place in many situations so it does A LOT of work. o Procedural Requirements: *can be supplanted/overridden by provisions in particular statutes. Rulemaking: process for making a rule. Rule = whole or part of an agency statement of general or particular applicability. Word “particular” is ignored, benign disregard for this provision, all act as if phrase is “general applicability.” Note: formal rulemaking is on-the-record, § 553(c) requires that agency follows the procedures set out in § 556 and 557. Involves taking of evidence by an ALJ through adversary trial-type proceedings, but can be more streamlined than formal adjudication. Adjudication: agency process for formulation of an order, anything other than a rulemaking. APA does not have to track constitutional definitions/requirements for adjudication, cannot afford you less rights, but can add more. Almost everything falls into this category, “whole or part of a final disposition…of an agency in any matter other than rulemaking.” Includes resolution of specific controversies between adverse parties, decisions to spend or not spend money, grant a lease, enter into or rescind a contract, licensing… Important distinctions: 1) definition of a rule and whether something falls in it 2) formal v. informal procedures. Formal procedures are triggered when relevant organic statute requires that the agency act on the record after opportunity for an agency hearing. This creates trial-type procedure for formal adjudication (before ALJ). 14 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 Rulemaking Adjudication All agencies have their own procedural rules, generally labeled “rules of practice” that elaborate, supplement APA requirements. If triggering language is ABSENT (and no LH), then agency is in informal adjudication, APA imposes essentially no requirements. What if there is some suggestive language but no magic words? Defer to agency for determination if statutory language is ambiguous. Dominion Energy Bayton Point v. Johnson (2006) 1. Dominion holds permit through CWA issued by EPA to pollute. 2. Renewed permit, EPA denied request for variance, no formal hearing, CWA only states that there must be “an opportunity for public hearing”—no magic words. 3. Issue = does agency get Chevron deference as to interpretation that no formal hearing is required. 4. Holding: EPA not required to provide an evidentiary hearing—Chevron deference is appropriate. Formal § 554, 556, 557 § 554, 556, 557 Informal § 553 (notice-and-comment) nothing *APA requires basically nothing for informal adjudication, but a fair amount for informal rulemaking (takes up to 1 year). o What does informal rulemaking entail? Notice of proceedings Opportunity to participate—anyone can submit a comment! Statement of basis & purpose Effective in not less than 30 days BUT…no right to cross-examine those you disagree with, must accept ALL comments (this is a lot more than is required by the legislature) *Statutes can impose requirements beyond APA, without requiring full on formal rulemaking (remember limitations on what court can require Vermont Yankee). *Formal rulemaking is VIRTUALLY NEVER DONE (so burdensome and “informal N&C rulemaking has become pretty comprehensive). o Comparison to § 556 and § 557 Apply to hearings, formal proceedings (i.e. formal adjudication) Presiding officer, ALJ, who has general control of the proceeding. Can present evidence, rebut, cross-examine. Laborious process, very slow. *Similar to Art. III trial o What does informal adjudication entail? No requirements by APA! § 554, 556, 557 inapplicable. SCOPE OF JUDICIAL REVIEW - Courts and deference—why have deference at all? o Congress chose to give agency this task, agency has expertise, can’t keep retrying facts, full review would be too much trouble for courts, courts just as political as agencies. o But…how much deference do we give? Different deference based on the question—fact, law, or policy (different ways agency decisions are made and then reviewed). Examples: 15 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 - Factual finding (question of fact): GHGs do or do not cause global warming. Legal interpretation (question of law): the statute does or does not require use to regulate GHGs causing global warming. Policy determination (question of policy): now that we have determined whether GHGs cause global warming and now that we have decided whether the statute does or does not require us to regulate GHGs, is regulating GHGs a good idea in light of our statutory authority? Review of Question of Fact o NLRB v. Universal Camera Corp. I. (2d. Cir. 1950) Issue = whether findings of the board (in reversing the examiner) were justified (question of fact, what effect to give to officer’s findings). Petition to enforce order of Labor Board, order was to reinstate supervisory employee named Chairman. Chairman had been discharged, claimed it was for hostile testimony he gave at a hearing against W conducted by board on another issue. Examiner hearing, not satisfied that W’s motive in discharging Chairman was reprisal for testimony. Board reviewed record, found the opposite, and reversed. Holding: Board’s order should be enforced. Board’s finding is within bounds of rational entertainment, cannot say that with all circumstances, no reasonable person could have concluded that Chairman’s testimony was one of the causes of his discharge. o Universal Camera Corp. v. NLRB (Supreme Court 1951) (foundational case!) Issue = effect of APA and the legislation of the Taft-Hartley Act on the duty of the Court of Appeals when called upon to review orders of the NLRB. Taft-Hartley: tried to conform statute to corresponding section of APA, substantial evidence test prevails, “questions of fact, if supported by substantial evidence on the record considered as a whole.” Courts must consider whole record, not just one side! Here, Court of Appeals had deemed itself bound by Board’s rejection of examiner’s findings—they are not! Examiner’s report is as much part of the record as the complaint or testimony. Holding: remand to Court of Appeals, on reconsideration of the record it should accord the findings of the trial examiner the relevance that they reasonably command. Looks first to organic act here, then says organic act is same as APA. § 706—scope of review (e)—formal adjudication, similar language to Taft, “substantial evidence” standard. o NLRB v. Universal Camera Corp. II (2d. Cir. 1951) Upon reexamination of record as a whole and upon giving weight to examiner’s findings, Board should have dismissed complaint. Holding: order reversed, complaint to be dismissed. o Result of Universal Camera Corp. cases: Peaking behind the standard to see, could a reasonable expert (i.e. the hearing examiner) come to and reached this factual finding? Look at the whole record! (could an unbiased person reach this conclusion?) Agency is least likely to be reversed on factual grounds than legal or policy. Question for reviewing court is always: is the agency’s decision supported by substantial evidence? o Allentown Mack Sales and Service v. NLRB (1998): (surprising reversal but not much precedential value because very fact specific circumstance) 16 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 - Allentown factory branch, sold, purchased under new independent dealership, 32/45 of Mack employees hired. Employees made statements suggesting that incumbent union had lost support. Union asked to be recognized, employer rejected, claimed good faith doubts about support for union. Board said no, Allentown had not demonstrated reasonable doubt, ordered Allentown to recognize union. Board had disregarded certain statements. these statements lead to reasonable uncertainty of union support. Board must draw all inferences that evidence fairly demands. Issue = whether the Board’s factual determinations in this case are supported by substantial evidence in the record. Holding: Board’s factual finding that Allentown Mack Sales had not demonstrated that it harbored a reasonable doubt based on objective considerations as to the union’s continued majority status, is NOT supported by substantial evidence on the record as a whole. Reversed Board’s decision and remand. o Zhen Li Io v. Gonzalez (7th Cir. 2005) Posner gets really mad at ALJ determination! Immigration judge ordered citizen of China seeking asylum deported. Board of Immigration Appeals affirmed. Immigration judge gave 5 reasons for denying application, Posner says immigration judge’s opinion cannot be regarded as reasoned, findings were actually incorrect. Holding: petition for review granted, vacate decision. *Q: is ALJ uninformed/overburdened or should we trust expertise? Posner makes factual assumptions as well! Often huge variation in ALJ decisionmaking. o Standard of Review: Formal Informal Rulemaking 706(2)(E) “substantial 706(2)(A) arbitrary or evidence” capricious Adjudication 706(2)(E) “substantial 706(2)(A) arbitrary or evidence” capricious 1. “Substantial evidence” v. “arbitrary or capricious” a. D.C. Cir. case: (Scalia) held that two standards afford same level of deference (even though Cong. used different words). i. BUT this does not mean that there is no difference between the two. ii. *This has become the adopted view of all circuit courts even though there has been no Supreme Court opinion. 2. Difference between informal and formal proceedings? a. Informal: agencies can make their decision based on arguments not shown or known by private parties, can add to the “record.” i. Easier time satisfying (hard look/arb. & capricious) standard, have more control over record in making factual determinations. b. Formal: record is only what has been presented or brought in via parties and ALJ decision. i. Harder to satisfy substantial evidence standard than arbitrary or capricious. Review of Questions of Law o When agencies interpret and decide meaning of statutes questions of LAW. o Legal determination trickier than facts: distinguish between pure questions of law versus application of that definition to the case. 17 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o o NLRB v. Hearst Publications (1944) Hearst refused to bargain collected with union representing newsboys because they are not required to bargain with people who are not employees. NLRB hearing, fulltime newsboys were employees. Court of Appeals reversed. Issue = whether newsboys were employees under the meaning of the term in the National Labor Relations Act. Board’s determination that specified persons are “employees” under this Act is to be accepted if it has “warrant in the record” and a reasonable basis in law. Task of defining term has been assigned primarily to agency created by Congress to administer Act. Holding: Board concluded that newsboys ARE employees, record sustains the Board’s findings, upheld. *Court really asked two questions here: 1) does common law govern the interpretation of the Wagner Act (question of law); 2) if not limited to common law, does employee include newsboys (application of law to fact). Question 1 court does not defer at all Question 2 court does defer significantly Why make this distinction? This is what Congress intended. (plus judge’s sense of their own desired roles) 1. Comparative expertise! a. Courts are as good as anyone at reading law books. 2. Comparative functionality/procedural advantage: a. Procedure of appellate courts are well-suited to answering the first question. 3. Comparative legitimacy: a. Courts are the legitimate expositors of law. b. Agencies are the legitimate managers of the economy. Skidmore v. Swift (1944) (sliding scale of deference! Gets rid of clear distinction between pure law and law to facts application from Hearst case) Employees brought action to recover overtime, administrator said hours spent in fire hall did constitute hours worked. Trial court reversed, Circuit Court affirmed reversal. Issue = whether hours spent in fire hall not actively answering the alarm constitute labor and whether any deference should be given to administrator’s interpretation. No principle of law found in statute or court decisions preclude waiting time as working time. Office of administrator has considerable expertise in this area. Opinion is not conclusive (not an interpretation of the act) but does constitute informed judgment, give it weight. Holding: evaluation of administrator’s opinion was erroneously restricted—reverse Circuit Court’s finding that hours spent were not hours worked. The Skidmore Standard: agency interpretations have persuasive authority whose weight depends on the circumstances (interpretive rules get Skidmore, not Chevron). Factors: thoroughness of agency consideration; validity of agency reasoning; consistency of the interpretation with past interpretations; any other factor that makes the interpretation persuasive (flip-flops). “The weight of such a judgment in a particular case will depend upon the thoroughness evidence in its consideration, the validity of its reasoning, its consistency with earlier and later pronouncements, and all those factors which give it power to persuade, if lacking power to control.” 18 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o o 2 things that were most influential were 1) whether agency’s interpretation was longstanding and 2) whether it was consistent. Changes in agency’s position with political tides less deference because it’s less consistent See Young v UPS (S. Ct. 2015): we’re not going to defer because the new interpretation is inconsistent with old interpretation. *After this, critique of courts for just making it all up. ***Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council (1984) CAA requires states to develop air pollution plans that require permits for construction of new major stationary sources, EPA promulgated rules that allowed states to define an entire plant (with many different pollution units) as if it were a single stationary source. Court of Appeals said statute did NOT permit EPA to create this “bubble-like” definition, would undermine Congress’s goal of speedy complain with national air quality standards. Issue = interpretation of the words “stationary source” in 1977 amendments to Clean Air Act and whether agency’s answer is based on permissible construction of statute. Court may not substitute its own construction of a statutory provision for a reasonable interpretation made by the administrator of an agency. Court of Appeals misconceived its role in reviewing regulations, its role should be deciding whether administrator’s view is reasonable. Holding: EPA’s use of bubble concept is a reasonable policy choice for the agency to make, definition of source is permissible construction of statute. Court of Appeals reversed. Deferred to agency because language of statute and clauses of the CAA indicated that Congress intended to enlarge the agency power to act (did not limit agency action by saying what it could or couldn’t do), here added language that suggested broad scope (i.e. can do anything to effectuate this). Complexity of field being regulated can be relevant, i.e. who has expertise. 2 KEY questions come out of Chevron: 1) Has Congress directly spoken on question at issue? If Congress has specific intention, then the end. If not, silent and ambiguous (second question) 2) Is the agency’s answer based upon a permissible interpretation of the statute? As long as it’s reasonable, your interpretation will be reasonable. Nets out with more deference to agencies. Post-Chevron: turn to more bright-line approach, if no Cong. speech then huge deference. Not looking at multiple factors, Court breaks new ground in invoking democratic theory—agencies are part of executive branch, political agent and court is not they are the preferred gap-filler because they are political, democratically accountable, and we are not. United States v. Mead Corporation (2001) (Chevron Step Zero “triggers”) Mead Corp. imports planners and 3-ring binders, at first these fell into category of goods exempt from tariff, then policy changed tax implemented. Sec. of Treasury establishes and promulgates rules and regs, U.S. Customs reclassified day planners as “diaries” resulting in change in tariff application. Issued a ruling letter, cannot be relied on and subject to revocation. Issue = whether a tariff classification ruling by U.S. Customs Service deserves judicial deference. 19 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o o Supreme court decide to treat Skidmore as default, Chevron did nothing to eliminate Skidmore holding about amount of deference owed. Chevron applies when Congress delegates authority and agency promulgates a rule in line with that authority. When Congress give you ability to act in formal ways and you do act in such a way, then you have interpretative agency—deference is given. What qualifies as formal? Trial adjudication, formal rulemaking (rare), notice-and-comment (and not even every notice-and-comment qualifies—some circuit courts have said no when agency says rules they promulgate don’t have precedential value and don’t have force of law). Here, on face of statute terms of congressional delegation gave no indication that Congress meant to delegate authority to customs to issue classification rulings with force of law. Classifications are best treated like interpretations contained in policy statements, manuals, and enforcement guidelines beyond the Chevron pale!! Holding: tariff classification has no claim to judicial deference under Chevron, no indication that Congress intended such a ruling to carry the force of law, BUT under Skidmore, ruling is eligible to claim respect according to its persuasiveness. Dissent (Scalia): anytime there is authoritative action by agency, deference should be given. Chevron should be the default presumption. Majority has put in a totally muddled world, leads agencies to act only in formal ways to try and guarantee themselves Chevron deference. *Scalia is least likely to defer to agencies because he is most likely to find clarity at step one—sees text as giving clear answer! Post-Mead: Must ask more questions about Congress’s intent to decide whether deference is warranted, less predictability. General principle of Mead suggests that informal adjudication usually will not merit Chevron deference. BUT Chevron certainly does apply to formal adjudications, trial type procedures governed by § 554, 556, 557 of APA and other not exactly formal proceedings but those with trial-type attributes. Skidmore generally applies when an agency has expressed views about the meaning of a statute it administers and Chevron is inapplicable. Barnhart v. Walton (2002) Holding: upheld Social Security Administration’s interpretation of “disability.” Agency’s interpretation was one of long standing, doesn’t matter that it was achieved through less formal “notice and comment” rulemaking. Whether a court should give Chevron deference depends in part upon interpretive method used and nature of question at issue. Here, nature of legal question, expertise of agency, importance of question to administration of statute, complexity of that administration, and careful consideration the agency has give the question over a long period all indicate that Chevron is appropriate legal lens. Gonzalez v. Oregon (2006) CSA regulates manufacture and distribution of certain drugs, AG sets out rules that physicians must comply with, can revoke licenses. Issue = whether AG’s interpretive rule determining that using controlled substances to assist suicide is not a legitimate medical purpose is valid. 20 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o o o Interpretive rule receives no deference under Chevron because although AG has rulemaking power to fulfill his duties under CSA, not authorized to make a rule declaring illegitimate a medical standard for care. CSA does not grant AG broad authority to make rules, limited power. Holding: no Chevron deference (failed Step Zero), under Skidmore follow an agency’s rule only to the extent it is persuasive, here AG’s opinion is not persuasive. 5 factor test to decide whether a practitioner’s registration is in the public interest—AG ignored these factors likely because would have lost on them. Also did not go through notice-and-comment rulemaking because likely would have taken too long. Long Island Care at Home v. Coke (2007): (unanimous opinion) Fair Labor Standards Act exempts certain categories from min. wage. Exempted from coverage certain subsets of employees including those in domestic service. Department of Labor promulgated regulation defining “domestic service employment,” exempted companionship workers. Issue = whether Department of Labor’s regulation is valid and binding. Dept. of Labor has rulemaking authority to define what employee includes, power to fill gaps left by FLSA. Used full public notice and comment procedures, no indication that Dept. did not intend for regulation to carry legal weight. Holding: regulation is valid and binding. Babbit v. Sweet Home Chapter of Communities for a Great Oregon (1995) (*Chevron Step ONE—did Congress speak directly enough to reject agency’s interpretation?) Endangered Species Act, contains protections designed to save animals from extinction. § 9 makes it unlawful to “take” any endangered species. Sec. promulgated reg. to define “take.” Includes indirect and direct actions. Issue = whether Secretary exceeded authority under ESA by promulgating this regulation. Court gets into reasonableness of interpretation, looks to ordinary understanding of words and dictionary definition, broad purpose of ESA, LH and Congress’s action in authorizing Sec. to use permits for activities under § 9. Holding: Secretary reasonably construed the intent of Congress when he defined “harm” to include “significant habitat modification…” Question of how many interpretive tools should be brought in under step 1? The more considerations you bring at step 1, less often you will actually get to step 2. Four Major Potential Formulations of Statutory Clarity for Purposes of Chevron’s Step One: After using every interpretive device at your disposal, and after exhausting all your interpretive efforts, an answer emerges as correct. After using every interpretive device at your disposal, and after exhausting all your interpretive efforts, an answer emerges as correct with a very high level of confidence. In other words, you end up (after your exhaustive review) fairly certain that your answer is correct. So courts must have great confidence in their interpretation to find a statute clear. After a relatively cursory review of the statute, an answer emerges as correct. The interpretation must arise from the words of the statute for a statute to be clear. After a relatively cursory review of the statute, an answer emerges as correct with a very high level of confidence. For a statute to be clear, there must be great confidence and the interpretation must arise from the words of the statute 21 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o o MCI Telecommunications Corp. v. American Telephone & Telegraph Co. (1994) 1934 Communications Act, long distance telephone carriers must file tariffs for services and rates with FCC, FCC can “modify” these requirements. Created a new rule that only AT&T was required to file tariffs. Issue = whether “modify” in Act allows FCC to promulgate such a rule. Look to dictionary defs, modify has connotation of increment or limitation. Change here is not mere modification, elimination of crucial provision of statute for 40% of major sector of industry. Unlikely that Cong. would leave such a determination to agency. Major Questions Doctrine: Congress does not hide elephants in mouse-holes. Questions of big economic and political importance wouldn’t just be delegated away, need some indication that Congress intended to delegate. 1. Keeps court in Step 1. 2. Ex: Utility Air Regulatory Group v. EPA (2014): CAA case, court said EPA’s interpretation is unreasonable because it would bring about an enormous and transformative expansion in EPA’s regulatory authority without clear congressional authorization. Holding: Act does not give commission authority to make such a fundamental change to the scheme. Dissent (Stevens): Dictionaries are extra-textual, must look to meaning in particular statutory context. Commission came to present policy through series of rulings that gradually relaxed filing requirements—regulation cannot be deemed unreasonable. *Is this a Step one opinion? Scalia writes it as one! But could also be a Step Two? could have easily been framed as agency’s interpretation of modify any requirement is unreasonable. Step zero? courts considering the importance of discretionary authority in context and likelihood that congress intended agency to make that decision. Flavor of what court is saying is that application of Chevron is influenced by enormous importance of decision and the unlikely fact that Cong. would delegate this decision in first place. City of Arlington Telecommunications Act of 1996 limits traditional authority of state and local govs to regulate wireless towers. FCC prescribes rules that are necessary to carry out act, issued a ruling on what a “reasonable time period” meant. Issue = whether court must defer under Chevron to an agency’s interpretation of a statutory ambiguity that concerns the scope of the agency’s statutory authority. Don’t separate jurisdictional and non-jurisdictional Qs, just about whether agency has stayed within bounds of statutory authority. If agency’s answer is based on a permissible construction of the statute that is the end of the matter. Dissent: Before a court can grant deference to an agency interpretation, it must on its own decide whether Congress has in fact delegated to the agency lawmaking power over the ambiguity at issue. need this delegation! Jurisdictional questions don’t get deference! Don’t get deference in deciding how much power you have to administer statute. 22 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o o If Congress has exempted particular provisions from authority then exemption must be respected. Food and Drug Administration v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp. (2000) (very broad Step 1 analysis) FDA concluded that nicotine was a drug within meaning of Food, Drug, Cosmetic Act and that cigarettes/smokeless tobacco were “combination production.” Thus it had jurisdiction to promulgate regulations intended to reduce tobacco consumption. Also had policy justifications for regulation. Issue: whether FDA had jurisdiction to regulate tobacco. Looks to other statutes, overall purpose (much more than just the text very broad step 1) wants to understand what has been woven into the law. FDA’s claim contravenes congress’s intent, Congress had directly precluded FDA jurisdiction on this issue. Cong. has considered and rejected 6 specific pieces of legislation permitting the FDA such jurisdiction. Decision is of economic and political significance, Congress would not have delegated. *Major Questions Doctrine comes up again! This regulation would impact major sector of the economy. MCI as instructive here. Holding: FDA’s assertion of jurisdiction is impermissible, Congress has precluded the FDA from asserting jurisdiction to regulate tobacco products. Court considers entire statutory scheme when determining authority that Congress delegated, not just piece at issue. big takeway from this case and O’Connor opinion! Dissent: Read too much into Congress’s considerations of proposal and inaction. After FDA asserted jurisdiction, silence from Congress—what to do with silence? Only wants to look at words of statute and their meaning (contrasted with majority approach). What is really going on here? Political battle! Should judges take this into account? Chevron allows this, new administration can come in and change policy, as opposed to Skidmore which values consistency over time. Massachusetts v. EPA (2007) Petitioned EPA to regulated GHGs under CAA. EPA denied petition to promulgate rule because it said it lacked authority under the statute to do so (CO2 not an air pollutant as the term is defined) this is the Chevron Q, and even if it did possess authority it would decline to regulate because regulation would conflict with other administration priorities Hard Look. Issue = whether EPA has statutory authority to regulate/whether reasons refusing to do so are consistent with statute. Agency has broad discretion to choose how best to marshal its limited resources, but refusals to promulgate rules are susceptible to judicial review even though it is limited and highly deferential. Holding: action was arbitrary, capricious, or otherwise not in accordance with law. EPA must ground its reason for action or inaction in the statute. Statutory text embraces all airborne compounds, repeated use of word “any.” Carbon dioxide fits within words of text. 23 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o o o EPA’s decision to not regulate rests on reasoning divorced from statutory text, EPA must make judgments as to whether an air pollutant causes or contributes to air pollution. Agency loses on step 1 because it is clear that CO2 is a pollutant under the CAA. Distinguished Brown v. Williamson, because EPA jurisdiction would not lead to extreme measures and no congressional action conflicts in any way with regulation of GHGs. Dissent (Scalia): Administrator gave reasons, policy judgments, but majority rejected them. Acted within law in declining to promulgate, text says nothing about what reasons the administrator may have for deferring making a judgment. Air pollutant defined in terms of air pollution, could reasonably mean only a ground level or surface of earth. Note: Williamson and MA v. EPA: Both have pretty aggressive Step 1, Chevron is really doing no work. Court is saying we can interpret the statute and the statute says X so you don’t get to not do X. In a world without Chevron these cases come out the same way—we interpret the statute and we’re done. Entergy Corp. v. Riverkeeper (2009) (Chevron Step Two—about whether the agency’s interpretation is “reasonable” or “permissible.”) Under CWA EPA regulates cooling water intake structure, requires that structure reflect “best technology available for minimizing adverse environmental impact.” EPA concluded that closed-cycle systems would impose far greater compliance costs and achieve only small gains—not justified by CBA. Issue = whether statute permits consideration of CBA. Minimize is a term of degree, looks to other provisions of CWA—when Cong. wished to mandate the greatest feasible reduction in water pollution, did so in plain language. Other provisions used “best” coupled with CBA language, not the case with this provision. Holding: EPA’s current practice is reasonable, legitimate exercise of discretion. (Scalia)—would be absurd to not consider cost at all. Concurrence (Breyer): statute doesn’t forbid CBA, legislative permits restrictively. Dissent (Stevens): forbids CBA, this is what canon of construction, expressio unius dictates. EPA has misinterpreted plain text. *Majority treats this as a Step Two case, Dissent as a Step One! National Cable and Telecommunications Association v. Brand X (2005) Act defines two categories of regulated entities: telecommunications carriers and information-service providers. Agency issues declaratory ruling that broadband internet service providers are information service providers. Previous court opinion held that cable modem services was telecommunications provider. Court of Appeals said that this holding overrode contrary interpretation reached by agency. Issue = proper regulatory classification under Act of broadband cable & what happens if before agency rules, a court rules on it? (can agency “overrule” that interpretation). If there is some ambiguity in the statute, then okay for agency to interpret, room for agency discretion (i.e. if there is a gap to fill). 24 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 - Why allow this? Agency as the best policymaker. If not, then would create a race to the courthouse—if you don’t like what you think agency will do, race to a friendly court and get judge to interpret statute differently. Holding: before a judicial construction of a statute, whether contained in a precedent or not, may trump agency’s, the court must hold that the statute unambiguously requires the court’s construction. Upheld agency interpretation. *Note: this issue does not come up often. o AT&T Corp. v. Iowa Utilities Board (1999) (example of Chevron Step Two LOSS— generally agencies otherwise always win at this step!) Local exchange carriers need to open up pieces of their network to competitors, if absence of access to these pieces would increase cost of competitor to enter the market. “Necessary and impair” standard. Issue = whether FCC rules are consistent with statute. Holding: commission has NOT interpreted the terms of the statute in a reasonable fashion. Act requires limiting standard, rationally related to goals of act, as to type of access afforded. FCC has failed to provide any, rendered “impair” meaningless inconsistent with normal FCC practice. Cannot mean nothing—whole section becomes surplusage because rule basically allows access to whatever element. o Auer/Seminole Rock Deference: Agency interpretation of an agency rule is controlling unless plainly erroneous or inconsistent with the regulation. Does not have a 2-step, and no Mead equivalent, get deference for everything. Must give effect to agency’s interpretation of its OWN regulation. LIMITS? When you parrot the statute itself, don’t get deference. Generally Auer very broad, courts will defer to positions expressed solely in briefs prepared for litigation. Auer wins you cases more often than Chevron! o Decker v. Northwest Environmental Defense Center (2013) CWA requires point sources to obtain a permit for discharge of water pollution, storm water not associated with industrial activity exempted. EPA said logging operations were covered by storm exemption. Holding: invoked Auer, statute and regulation ambiguous, no independent analysis done on regulation’s meaning, accepted EPA’s interpretation. Dissent (Scalia): Rejects argument that agency knows what it means, Scalia says we know what words mean, don’t need to defer. Chevron Recap: o No consensus on when Step Zero kicks in. o No consensus on what tools of statutory construction to use at Step One (LH, enacted and unenacted statutes), no consensus of level of confidence needed. o Agency almost always wins at Step Two. Step Zero: did Congress delegate general authority to the agency to make rules carrying the “force of law” and did the agency promulgate the interpretation in question in exercise of that authority? (Mead). Grant of authority can be implicit through: 1) generally conferred authority; or 2) other statutory circumstances indicating that Congress expected the 25 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 agency to speak with the force of law when addressing ambiguity or gap filling. Invalidate regulation if interpretation is impermissible. *Note major questions doctrine may also come up here, See Gonzalez. Generally speaking, look to notice-and-comment rulemaking or formal adjudication presume to have acted with force of law because jumped through procedural hoops. NOT a bright line rule, Congressional intent = lodestar. Sometimes agencies will act with less than procedural formality and court will find acted with force of law. 1. Ex: Barnhart case, indicia of force and rigor to process creating interpretation to warrant Chevron deference application. 2. Note: if good cause exception invoked, no n&C, then Skidmore over Chevron deference. Step One: has Congress directly decided the precise question at issue? Turns on how many tools of statutory interpretation that the court has employed. (step one ends up looking a lot like any other statutory interpretation issue). Confidence Issue: two ways to view Step One: can use statutory interpretation tools to determine meaning, or if cannot determine without extrinsic tools then you just move onto step two if not on its face clear. Tools: Statutory text Dictionaries Legislative history Other statutes Context Absurdity Grave constitutional avoidance (regulations must pose “grave and doubtful constitutional questions before constitutional avoidance triggers). Qualifications: Major Questions Doctrine really a STEP ZERO QUESTION. (Brown v. Williamson, affecting how they considered the issue in the first place). 1. It would be a remarkable intent to attribute to Congress that a few stray words in a provision empowered an agency to change a massive aspect of the economy. 2. Note: tension between Brown and MA v. EPA, where in latter case agency is actually being told they have to regulate a big issue. Could argue that this is not a mousehole, air pollution is a capacious term. Context counts (there is no effectively irrefutable presumption that the same defined term in different provisions of the same statute must receive identical interpretations. Duke Energy Corp.) Jurisdictional rules (no difference between agency interpretation regarding jurisdictional and non-jurisdictional grants). Broad Discretion (when Congress has entrusted the agency with broad discretion, the court is reluctant to substitute its views of wise policy. Babbit) Immigration context (judicial deference in the immigration context is of special importance because executive officials “exercise 26 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o o especially sensitive political functions that implicate questions of foreign relations.” Negusie.) Step Two: agency determinations stand if “permissible” or “reasonable.” Overrule an action only if: 1) is inescapably precluded by the statute or 2) “arbitrary or capricious” in substance. Note: Step 2 and hard look often look similar but have different implications. Note: what doesn’t get Chevron deference? Agency litigating positions, articulated for the first time in briefs. Agency acting as a prosecutor No deference for interpreting statutes also administered by other agencies, like APA. Ex: EEOC does not get deference for interpreting Title VII. Typically not applied to informal adjudication, policy statements, or general guidance. Probably because informal adjudication is usually about question of fact not law (where Chevron always applies). Policies underlying Chevron: Agencies have edge over courts in accountability and technical expertise. Deference reduces the disparateness and balkanization of federal administrative law by limiting the number of circuit conflicts. Incentivizes Congress to write laws with greater precision. Congress implicitly delegated law-interpreting powers. II. ARBITRARY AND CAPRICIOUS/“HARD LOOK” REVIEW - Legal determinations v. policy: o Legal: when statute is totally ambiguous o Policy: statute not ambiguous, a lot of power given to agency to make a judgment, authority to make a policy call. - Steps involved in setting a standard: o Agency must obtain accurate information o Agency must determine an overall approach to determining the stringency of the standard it will promulgate. o Agency must consider a host of questions related to the type/form of standard it wishes to promulgate. o Agency must modify or shape the standard in light of enforcement needs. o Agency should take account of various competitive concerns. o Agency may have to negotiate a final standard with relevant groups. o The standard must survive judicial review. - Arbitrary and Capricious Review o Note: “substantial evidence” standard applies only to formal adjudication, we are talking about informal now. o Concerns about agency capture lead to development of “hard look” review. Judges must ask: “did the AGENCY take a hard look at facts, data, arguments presented to it?” (not about what court did) May sometimes involve how agency could have come to the conclusion, even if that wasn’t the thought process that was actually taking place. The point is to get agencies to explain their decisions, cannot just look at procedure or bare minimum reasonableness. o Hard look review is highly contextualized, based on the framework established by the relevant statutes, agency’s program and policies, past and present, issues in particular case, the record, and contentions advanced by those opposing agency action. 27 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o - *How does an agency figure out what language they need to respond to (to constitute a hard look)? Reasonable alternatives (significant and viable), not every alternative device ever conceived. Anyone can submit comments for agency to respond to, must also respond to dissenting opinions on multi-member commission boards. Place yourself in judge’s shoes, anticipate what they might point out is important. o A rule is arbitrary and capricious if the agency: relied on factors that Congress did not intend the agency to take into account or failed to account for factors required by any authoritative source of law; the action does not bear a reasonable relationship to statutory purposes or requirements; the asserted or necessary factual premises of the action do not withstand scrutiny under the relevant standard of review; the action is unsupported by any explanation or rests on seriously flawed reasoning; the agency failed to give reasonable consideration to an important aspect of the problems presented by the action without adequate justification, like effects, costs, or factual circumstances; the action is inconsistent with prior agency policies or precedent, without adequate justification; the agency failed to consider or adopt an important alternative solution to the problem, without an adequate justification; the agency failed to consider substantial arguments—or respond to relevant and significant comments—made by participants in the proceeding that gave rise to the agency action; the agency has imposed a sanction generally out of proportion to the magnitude of the violation; the action fails in other respects to rest on reasoned decision-making. Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe (1971) o Organic statute prohibits Sec. of Transportation from authorizing use of federal funds to finance the construction of highways through public parks if “feasible and prudent” alternative route exists. If no route exists, must take steps to minimize harm. Informal adjudication takes place. o Sec. announced highway to cut through park. Petitioners sued. o Issues = whether petitioners are entitled to review and under what standard. 706(2)(A) APA: a reviewing court shall hold unlawful and set aside agency action findings and conclusions found to be . . . “arbitrary, capricious, or an abuse of discretion.” this is the standard to be applied in this case! Petitioners try to argue that standard is “substantial evidence” (2)(E) or de novo review (2)(F). BUT substantial evidence is only for formal rulemaking or adjudication. This is an informal adjudication (look to organic act, no formal procedures), for which APA prescribes nothing. Under arb./capricious standard, court must decide whether secretary acted within scope of authority, if did act within authority, require a finding that actual choice made was not arbitrary, capricious. “To make this finding the court must consider whether the decision was based on a consideration of the relevant factors and whether there has been a clear error of judgment. . . . Although this inquiry into the facts is to be searching and careful, the ultimate standard of review is a narrow one. The court is not empowered to substitute its judgment for that of the agency.” 28 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 - - NOT a rubber stamp (agency must really justify decisions it makes and how it reaches them). o Holding: remand, Sec. failed to make formal findings as required for hard look review. No specific procedures required but review must be probing and on the FULL administrative record. How do you get information about how agency made its decision? Not legal affidavits Can inspect procedures of agency (but this case does not require any specific procedures). If there is an inadequate record, can get depositions of decision-makers. But if there are administrative findings, need strong showing of bad faith or bad behavior to allow investigation into decision-makers. Conclusion: paper these decisions over! Leave a hefty paper trail. (although technically there is no formal requirement of what to do, but as a practical matter, agencies will take action and compile a record). Motor Vehicle Manufacturer’s Association v. State Farm (1983) (first S. Ct. direct affirmance of “Hard Look” Review!) o National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act directs of Sec. of Transportation to issue motor vehicle safety standards. Regulation has complex history: 1966 statute passed, 1967-72 formulation of standard that would require full passive protection for all (automatic seat belts). 1976 Sec. suspends passive restraint requirement. 1977 Sec. mandated either airbags or belts. 1981 Sec. modifies regulation, people will detach automatic belts, so longer a basis for reliably predicting that the standard would lead to any significant increased usage of restraints at all. o Act called for standard to be promulgated under informal rule-making procedure of § 553 APA. action may be set aside if found to be arbitrary and capricious. Gov. tries to equate rescission of statute to refusal to promulgate (because this would get greater deference), court says no, this is like promulgating any other action. o Organic statute required record. Agency must examine relevant data and articulate a satisfactory explanation for its action including a rational connection between facts found and choices made. Agency failed to consider requiring airbag installation (don’t have to adopt it but must explain why not), thought agency also should have considered evidence about people not detaching detachable seatbelt (inertia). o Holding: agency failed to present an adequate basis and explanation for rescinding the passive restraint requirement. Agency must either consider the matter further or adhere to or amend the standard along the lines which its analysis supports. Massachusetts v. EPA (2007) o EPA denies rulemaking petition. Agencies have discretion but here because denial of petition for rulemaking this is different than just not prioritizing it. Decision to deny IS reviewable. Agency can deny, that is within their discretion. But that decision is reviewable, so under hard look review need to show that they put in work, here is WHY they denied. Need an action for hard look (doesn’t work for inaction cases) can’t say you failed to take a hard look at something you didn’t do. o Only question is whether this decision threatens the health of citizens, “judgment” is not a roving license to ignore statutory text. o If scientific uncertainty is so profound then EPA must say so! its because they didn’t make this call that it failed under hard look and was “arbitrary and capricious.” 29 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 - - FCC v. Fox (2009) o Communications Act prohibits use of profanity, 2004 declares that nonliteral expletive use of “F” and “S” words could be actionably indecent, even if word is only used once. o Fox aired Billboard Music Awards, two incidents of curse words. o Holding: new enforcement policy and order NEITHER arbitrary nor capricious. Agency was free to decide that the old regime no longer tracked its overall enforcement policy. No heighted standard despite change in policy APA does not mention such a standard and statute makes no distinction between initial action and subsequent agency action. Majority says must show that new policy is reasoned, but also acknowledge that you are CHANGING your position (cannot just disregard change and pretend policy has always been that way). BUT don’t have to show that new policy is better. Here, commission acknowledged change, disavowed old policies, reasons were rational. o Dissent (Breyer): FCC is an independent agency, broad authority to determine relevant policy, but does not permit them to make policy choices for purely political reasons nor to rest them primarily upon unexplained policy preferences. Should have different review for independent agencies. Agencies must answer Q: WHY did you change (more than acknowledging change)? o 3 significant things going on in this case: Hard look—no added burden, besides acknowledging change in mind. Level of justification for changing mind *After Fox, agency that is changing its position must at least acknowledge the change justify the new position on the merits. Need not directly compare the old and new policies and explain why the latter is preferable. Independent agencies (don’t get treated differently) + empirical evidence (if there is scant empirical evidence, don’t have to come up with it (don’t have to obtain the unobtainable). o Why isn’t this Chevron instead of “hard look?” Its not about interpretation of word “indecent,” it is just about change in policy so Chevron cannot apply. Step Two v. policy judgment: At Step Two invalidate interpretation, interpretation is impermissible and come up with a different one. Policy go back and take a second look, take that “hard look”—can come to same conclusion. In some ways level of deference of “arbitrary and capricious” and step two are similar, but looking at different materials! Arent v. Shalala Hard look = tell us what you looked at Chevron = its about authority to act (step 2—don’t care how agency came to conclusion). Why have hard look review? We don’t ever think that agency goes into meeting with an open mind, but maybe sometimes it will change its mind, at least at the margins! May be persuaded. Michigan v. EPA (2015) 30 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o - III. - EPA must consider costs. Interpreted the CAA unreasonably when it determined that it did not need to consider costs when it issued a "finding" that it was "necessary and appropriate" to regulate. Agency Bias in Rulemaking o Need: “clear and convincing evidence” of an “unalterably closed mind.” o Courts have been reluctant to find this standard. o Cinderella Career & Finishing Schools v. FTC (1970) FTC brought a complaint against Cinderella School for false claims, hearing examiner dismissed, appealed. Holding: FTC erred in overturning the decision of its hearing examiner without adequate reason. Chairman of FTC had participated in decision, had previously made a speech that indicated his beliefs about culpability of school. Test for disqualification = whether a disinterested observer may conclude that the agency has in some measure adjudged the facts as well as the law of a particular case in advance of hearing it. Litigants entitled to an impartial tribunal. o Association of National Advertisers v. FTC (1980) Chair of FTC gave a speech suggesting that advertising aimed at children harms them, suggested commission take action. Commission issued a notice of proposed rulemaking that considered banning televised advertising of sugar products on children’s programs. Advertising associations moved to disqualify P under Cinderella. Holding: a commissioner should be disqualified only when there has been a clear and convincing showing that the agency-member has unalterably closed mind on matters critical to the disposition of the proceeding. Never intended Cinderella to apply to rulemaking. Legitimate function of a policy-maker, unlike adjudicator, is to engage in debate and discussion. RISK REGULATION Regulation of Carcinogens o Practical problems that regulatory agencies like OSHA, EPA, FDA deal with when evaluating potential cancer-causing substances. Defining what “safety” means. Outlining proper regulatory objectives Finding the right “does-response” curve. How to accurately test for risk. Using experts. o Cost-Benefit Analysis Methodology Many people favor CBA on economic grounds: want regulation to be efficient. Others think CBA helps to overcome people’s errors in thinking about risks. On the other hand, CBA is incompletely specified, much needs to be done how relevant variables should be valued. Seems logical to try and reduce largest risks first, this would not necessarily result in the most efficient reduction in risks because our ability to reduce risks is not constant—some risks costs more than others. IV. PROCEDURAL REQUIREMENTS IN AGENCY DECISIONMAKING - How do you get rid of old administration’s regulations? o If it hasn’t yet gone into effect, can simply step in and stop it. 31 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 Discretion that new administration has ex: gas mileage regulations. If predecessor issued only guidance, can undo through new guidance. Least common form of rollback (because most rules are made through notice-and comment). Ex: transgender rules from Obama administration. o Congressional Review Act: fast-tract legislative repeal of regulations that have been promulgated in the last 6 months. Has been used a lot more recently (4 times), prior to this administration has only been used once! No filibuster allowed—easier to get rid of rules than create new ones. o Implement new regulations to replace old (State Farm case) Time consuming process Can always do this (new administration or not) o If you had an initial policy decision through an adjudication, need either a new adjudication or a rulemaking to supersede old adjudication. Cannot have done original policymaking through rulemaking and then try to change through adjudication, need new notice-andcomment. If an agency is changing its mind about a policy, must change it through adjudication or rulemaking and also acknowledge and explain why you are changing it. Choice between rulemaking and adjudication o Agencies are understood to have the choice (if they have authority to do so). Usually an agency may choose rulemaking. However, think Londoner, if issue is specific to a narrow group of people, adjudication with DP protections may be necessary instead of a rule. o Generally speaking there has been a move from adjudication to rulemaking. Beefing up of requirements of rulemaking. o Why choose rulemaking over adjudication? Create more general rules instead of case by case specifics, allows more parties to be involved. All parties treated the same—fairer outcome. Agencies not bound by adjudication (just like courts) BUT agencies ARE bound by rules. Can improve quality of rule, get something that is procedurally fairer. Scope of judicial review (can be hard to win in an adjudication). Priority setting—adjudication can only decide what is in front of you v. rulemaking—can decide what you want to rule on. Longevity: bind your successors in rulemaking Formal adjudication is VERY burdensome—ALJ, independent of agency, you can’t control anything! NLRB v. Wyman-Gordon (case not assigned) o NLRB tried to create a prospective only adjudication decision. o Issue = is this permissible? o S.Ct. split—plurality said if prospective only then it is really just a rule. o *At this time move towards rulemaking anyway, so limits on adjudication didn’t end up being that meaningful. BUT note that shift to rulemaking does NOT eliminate adjudications. Adjudications are still required when: an agency considers an application for a permit or a license or benefits and when it enforces the requirements set out in the relevant statute or in its own regulations. National Petroleum Refiners Association v. FTC (1973) o - - - 32 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o - - - Issue = whether FTC can promulgate substantive rules of business conduct under its governing statute. o Section 6(g): Commission may from time to time make rules and regulations “for purpose of carrying out the provisions” of this act. o Commission will be able to proceed more expeditiously, give greater certainty to businesses subject to act with a mixed system of rulemaking and adjudication than just adjudication alone. o Holding: under terms of statute, FTC is authorized to promulgate rules. *Fundamental proposition that agencies have only those powers they have been granted by statute. FPC v. Texaco (1964) o FPC adopted through notice-and-comment rulemaking, regulations governing the terms of contracts between natural gas producers and pipelines. o Holding: Can have a rule that makes adjudication less meaningful: particularize statutory standards through rulemaking process that bar threshold adjudication claims. If you don’t like this then you can contest the rule! American Airlines o Through rulemaking an agency can change right to a license. Heckler v. Campbell (1983) o Sec. of Health and Human Services adopted regulations, established through rulemaking the types and number of jobs that exist in the national economy as part of determination of whether a disability claimant retains the ability perform work. o Where a claimant’s qualifications correspond to job requirements identified by a rule, claimant is not considered disabled. o Campbell, hotel maid with back condition, denied disability, guidelines said she could perform other jobs that existed in national economy. Claim of right o present evidence and relevant facts (in adjudication) o Issue = whether use of these guidelines is valid. Court rejects arguments that petitioner can present individualized evidence. Sec. can rely on rulemaking to resolve certain classes of issues, can do this in advance of adjudication. o Holding: Sec.’s use of medical-vocational guidelines does not conflict with statute, nor are they arbitrary and capricious. *Moral of the story: agencies can do a lot through rulemaking even when there is a statutory requirement for a hearing (but some things require individual determination). Formal On-the-Record Rulemaking o Rulemaking MUST be formal if organic act calls for a “hearing on the record.” (magic words!) o United States v. Florida East Coast Railway (1973) Issue = whether Act provision calls for a formal rulemaking. § 556 and 557 apply if organic act uses words “after hearing on the record.” § 1(14)(a) uses the words “after hearing” but not “on the record” not enough to invoke 2 sections of the APA (doesn’t match closely enough the language of § 553(c) which triggers 556 and 557). This result is dictated by precedent, Allegheny-Ludlum Steel Corp. Holding: Commissions’ proceedings were governed only by § 553 of the APA, appellees received the “hearing” required by the Act (did not require formal rulemaking). But note that just because APA isn’t invoked, doesn’t mean that there are no requirements—there can be independent requirements. 33 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 - *This case is significant because this statue is about as strong a case as “hearing” means “hearing on the record” as one could present. Background of this case: pronounced increase in agency rulemaking and desire to escape long delays and resource burdens involved in formal adjudications, procedures of formal rulemaking found to be inordinately cumbersome and time-consuming. Some lower courts have said that formal adjudication can be required without magic words BUT NO court has said that statute minus magic words can require formal rulemaking. *Most things are done in informal rulemaking!! Very very few formal rulemakings today! (only formal adjudication). Informal Rulemaking o Almost NO procedural requirements—just need to know how you reached your decision (Overton Park) o § 553 of APA: general notice of proposed rulemaking § 553(b) Need general statement, concise, has purpose Statement of time, place, nature of rulemaking Reference to legal authority § 553(c): Interested parties can submit comments Issue of final rule must include concise statement of general purpose o United States v. Nova Scotia Food Products (1977) FDA conducted notice-and-comment rulemaking, promulgated safety regulations for smoking of fish to safeguard against botulism. Enforcement proceeding, sued to stop Nova Scotia from processing hot-smoked fish in violation of regulations. Issue = whether agency provided enough evidence of its decision to allow for adequate judicial review on whole record and thus showed it took all relevant factors into account when making regulation. *Hard look review informing court’s opinion, but doesn’t strictly apply it because court says this is about problems in the process, procedural problems: relied on scientific data that no one knew about. Holding: reversed lower court’s grant of injunction, dismissed complaint against corporation. No contemporaneous record made, FDC provided only cursory responses to some important suggestions and no responses to others, never acknowledged whether proposed regulation was commercially feasible. Case demonstrates how court built on requirements of § 553 to transform notice-and-comment procedures into more elaborate “paper hearing” process that generates documentary record and full agency opinion as basis for “hard look” review. Read “meaningful” comment into § 553, in order for groups to be able comment meaningfully, need to be able to access all information (i.e. scientific data agency is relying on). o Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Corp. v. Natural Resources Defense Council (1978) Issue comes up with licensing, agency creates a rule to deal with one licensing issue. Underlying rule challenged. 34 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 - D.C. Cir. (most important court in admin law—perceived to be more hostile to agencies, more sympathetic to enviro groups), had concerns that rulemaking procedures failed to allow for adequate probing. Issue = whether APA requires more than informal rulemaking (i.e. whether commission should have required further elucidation on certain subjects). Agencies are free to grant additional procedural rights in the exercise of their discretion, but reviewing courts are generally not free to impose them if the agencies have not chosen to grant them. If courts could continually review agency proceedings to determine whether the agency employed procedures which were, in the court’s opinion, perfectly tailored to reach what the court perceived to be the “best” or “correct” result, judicial review would be totally unpredictable. Holding: S. Ct. says no to D.C. Cir.—cannot ask for more in rulemaking procedures, courts have no legal authority to go beyond § 553, cannot add additional requirements. *Vermont Yankee reads the APA to preclude, absent unspecified exceptional circumstances, judicial requirements that agencies use additional procedures beyond those specified in the APA or other relevant statutes. BUT explicit paper hearing or hybrid rulemaking requirements imposed by statute (like those established under the CAA) survive Vermont Yankee. No new requirements can be imposed upon APA onto agencies in informal rulemaking. o Sierra Club v. Costle (1981) Issue = whether off-the-record meeting between agency and president is allowed when an agency is promulgating a rule and thus doesn’t include contents of meeting on record. Need key policy makers to be able to talk to each other! Interaction with president do not need to be on the record. “Our form of govt simply could not function effectively or rationally if key executive policymakers were isolated from each other and from the Chief Executive” Holding: CAA did not prohibit off-the-record meetings and Vermont Yankee precluded the court form imposing its own rule to that effect. Arguments of policy from public must be disclosed, hard science disclosed. o Vermont Yankee v. Hard Look v. Pre-Vermont Yankee Hard look: did you agency think carefully about what you information you have? Comments, data, reports? Pre-VY: agency you let everyone in the world know all arguments made, you let other people have the maximum amount of information. VY: court cannot impose new requirements. Contemporary (INFORMAL) Rulemaking Process o What is required of NPRM? Find a rule that must be a logical outgrowth of proposals in NPRM—some wiggle room here (implicit in § 553). Agencies must show their hand (put on notice) at time of promulgating NPRM, disclosing as much relevant data as possible. Must public NPRMs that afford interested parties an opportunity to participate. o Long Island Care at Home v. Coke (2007) Issue = whether notice-and-comment procedure leading to promulgation of rule was legally defective because notice was inadequate. 35 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o V. - - - Agency must publish in its notice, either the terms or substance of the proposal rule or a description of the subjects and issues involved. Department initially considered a rule that would include third-party companionship workers in exemption. Then withdrew proposal. Reasonably foreseeable because department was just considering initial proposal. Requirement of FAIR NOTICE: if agencies propose X, can still also do less than X, gives basic notice, don’t need to revise everytime. Holding: procedure was not legally defective—notice adequate. *Note: some agencies have begun to issue Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPR), common in major rulemakings for agencies to issue this first, identify general nature of proposed rulemaking, solicit comments. Then agency will use a more specific proposed rule on which it will take comments before issuing final rule. Many key convos happen before rulemaking takes place! Can avoid notice-and-comment by implementing policy or interpretive rules: Interpretive rules are clarifications and non-binding no force of law so no Chevron deference. If practically binding (though not “legally” binding), may require notice-andcomment. If creating binding norm then requires notice-and-comment rulemaking. EXCEPTIONS TO NOTICE-AND-COMMENT REQUIREMENTS The current state of procedural requirements: o Informal adjudication = required to give something to a court o Formal adjudication = basically article III judges o Informal rulemaking = hard look + procedural requirements Procedural requirements bare language of APA requires very little, but in reality rulemaking has become very time consuming. Rule has to be: 1) logical outgrowth from proposals in NPRM 2) at time of promulgation show your hand with all data you possess 3) publish NPRMs to afford parties opportunity to participate. This adds up to a ton of pre-work for agencies when issuing NPRMs! Hard look: don’t have to reveal information itself, but hard look is about agencies internal processes—how it responds to comments, information, etc. Hard look and procedural requirements are related but can have one without the other. Notice-and-comment has become a much more elaborate process than you might guess from bare words of § 553. What does this mean? Take a lot longer. People don’t actually have input until later on in the process (agencies do a lot of pre-work). Should we change things? o E-rulemaking to de-ossify the process? Does this work though? Million comments, generally ignored anyway, doesn’t affect rule, agencies seem to pay no attention. o If we actually care about public opinion are comments the way to do it? Those who comment misrepresent society, all higher income, higher educated people not a random sample of “we the people.” Exceptions to § 553 36 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o o o Agencies have a non-trivial interest in avoiding § 553, incentive to find that you are subject to an exception (see below!): Any organic act counts over APA. Congress can say (explicitly or not) no need to comply with § 553, i.e. promulgate within 15 days everyone understands that 553 doesn’t apply. Military/foreign affairs excluded entirely (APA says so). Agency management, personnel, benefits (i.e. combing photocopy departments). Public property, loans, grants Interpretive rules, general statements of policy, rules of agency organization, procedure, or practice ((b)(3)(A)) Interpretive rules = allows agencies to explain ambiguous terms in legislative enactments without having to undertake cumbersome proceedings. Statements as to what an administrative officer thinks the statute or regulation means (in comparison to legislative law which creates law). General policy statements = allows agencies to announce their “tentative intentions for the future.” (note a policy statement is different than a question of policy) 2 criteria test: 1) does the statement of policy have a present effect (it cannot); 2) whether a purported policy statement genuinely leaves the agency and its decision-maker free to exercise discretion. Rules of agency organization, procedure, or practice = ensure that agencies retain latitude in organizing their internal operations. Focus on whether agency action also encodes a substantive value judgment or puts a stamp of approval or disapproval on a given type of behavior. Impracticable to public interest (“good cause” exception) ((b)(3)(B)) Often invoked to speed up process, if regulation needs to be promulgated in short period of time, need to act quickly. If you cannot invoke a good cause exception, 2 options: Promulgate through notice-and-comment anyway Promulgate rule that is not formally legally binding (i.e. interpretive rules—not legally binding on the rule) 1. “Formally binding” = legislative or substantive rules American Hospital Association v. Bowen (1987) Congress enacted legislation requiring creation of Peer Review Organizations to oversee expenditure of Medicare Money. Dept. of HHS promulgated regulations concerning organization of PROs. Did not follow notice-and-comment procedures. Holding: rules and regulations were procedural in nature (exempted under 553(b)(3)(A)), another regulation that defined substantive terms of contracts were statements of policy (exempted under 553(b)(3)(A)). *Note: substantive rules grant rights, interpretive rules clarify pre-existing obligations. Appalachian Power Co. v. EPA (2000) Without notice-and-comment, EPA issued monitoring guidance docs. Issue = if an agency claims its rule is interpretive but is treating is it like a binding rule what do you do? (do guidance documents fall into a 553 exemption) 37 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 VI. - - - - Holding: guidance document here “commands,” “requires,” and “orders.” For all practical purposes it is binding, so cannot fall within an exception to 553, need opportunity for notice-and-comment. CONSEQUENCES OF THE TRANSFORMATION OF NOTICE-AND-COMMENT RULEMAKING Legislative v. Interpretive Rules: norm now is that rulemaking takes at least a couple of years, this is why agencies may want to avoid notice-and-comment rulemaking and invoke exceptions. o *From an agency standpoint not going through notice-and-comment is potentially dangerous, makes you more vulnerable. Agencies prefer to secure their rules. Don’t get to rely on interpretive rules but certainly are persuasive and can note in your brief. Don’t need n-and-c to change interpretive rules. o Interpretive Rules: alternative to legislative rules, doesn’t actually bind, interpreting previous rule or creating policy, not imposing any new laws, just clarifying what was implicit. Everyone agrees if formally binding must go through notice and comment, but even sometimes if not formally legally binding, may still need to go through noticeand-comment because practically binding. o Community Nutrition Institute v. Young Rule or interpretation? If you ever want to rely on it, must do notice-and-comment rulemaking and make this choice in advance of reliance. Court says doesn’t look like statement of policy, FDA treating it as binding effect. o United States Telephone v. FCC If you yourself treat it as a rule, then it will be a rule (and thus need notice-andcomment). o Guidance documents: different than interpretive rules—key is they both don’t cabin agency discretion. Guidance on guidance, some suggestions for what should happen in order to issue guidance, insert rigor into guidance so people will take them seriously. Ways to get rid of regulations: o CRA: need simple majority to get rid of regulations o Legislation that changes everything (coming out of Congress) o Rescind regulations you don’t like: rescind with adjudication, notice-and-comment. Mere guidance rescind with new guidance. o *Remember: rescinding and creating new regulations are done in the same manner. Usually most major regulations take 1 year to promulgate, if statute gives you authority to promulgate without notice-and-comment then you utilize this procedure. Negotiated Rulemaking (Reg Neg) o Develop rules through a process of negotiation. o Can speed up overall process, produce better rules and lead to greater compliance (greater buy-in), may also narrow range of disagreement. o Drawbacks? Can distort proper role and responsibility of an agency (reduces agency to level of mere participant). Also issues of who is at the table and what kind of participation is appropriate. o Rarely done (only 10% of rulemakings) Rules of Procedure: o Procedural rules do not substantially alter rights, don’t encode value judgment. If you really want to do something substantively need legislative rule. o Leads to creation of made up terms: “Interim-final rules” and “Direct-final rules” 38 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 - Interim-final rules = we have good cause to impose this rule immediately, but we are going to try and cover ourselves and call it an NPRM therefore if you lose in court over good cause, already on their way to creating a rule. ***If you don’t go through notice-and-comment don’t get Chevron later down the line! Procedural Constitutional Rights o SEC. v. Chenery Corp. I (1943) Chenerys were officer, directors, controlling SHs of Federal Water Service Corporation, public utility holding company subject to reorganization under Act. Respondents negotiated with SEC over terms of proposed voluntary reorganization, had purchased shares of preferred stock during reorganization. SEC round that this violated duty of fair dealing, preferred stock would not be converted. Relied on principles from prior cases (common law). Longstanding equitable principle to not let managers buy such shares. However court finds no such longstanding principle exists. Holding: SEC’s order cannot be upheld. There must be actual responsible finding and there is no such finding here. Congress did not proscribe respondent’s conduct, nor has SEC promulgated new general standards of conduct. *Rule of Chenery I: No post hoc rationalizations at litigation, need to show argument is actually one you considered at time of problem. (Absolute bed rock rule!! Need to articulate what you are basing decision on). “But the difficult remains that the considerations urged here in support of the Commission’s order were not those upon which its action was based.” Must put in all the best arguments before litigation! o Chenery on Remand: SEC disavowed any intention to create a new rule. Covered Chenery I by explaining that they did rely on their expertise. Reaches same result as before remand. o Chenery II Responding to new SEC decision. Latest order of Commission avoids fatal error of relying on judicial precedents which do not sustain it. Did not mean to imply in previous decision that failure of Commission to anticipate this problem and to promulgate a general rule withdrew all power from that agency to perform its statutory duty. (only alternative was NOT just to approve proposed transaction) Can make policy through administrative adjudication (refuse to say that Commission was forbidden from utilizing this particular proceeding for announcing and applying a new standard of conduct). Holding: unable to say that SEC erred in reaching result it did. Commission made an informed, expert judgment on the problem. Chenery II Takeaways: Totally up to agency to use rulemaking or adjudication. And you can have a new approach/principle that applies retroactively 1. *some limits on this, how far back retroactivity can go (not always accepted). a. Retroactive adjudications are limited by a 5-factor analysis: i. Courts have not infrequently declined to enforce administrative orders when in their view the inequity of retroactive application has not been counterbalanced by sufficiently significant statutory interests. Among the 39 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 - VII. - - - considerations that enter into a resolution of the problem are: ii. Whether the particular case is one of first impression iii. Whether the new rule represents an abrupt departure form well established practice or merely attempts to fill a void in an unsettled area of law. iv. The extent to which the party against whom the new rule is applied relied on the former rule. v. The degree of the burden which a retroactive order imposes on a party vi. The statutory interest in applying a new rule despite the reliance of a party on the old standard. 2. See Bowen v. Georgetown University Hospital: S.Ct. says retroactivity not favored by law, will not assumed retroactivity unless there is clear language in the statute that provides for retroactivity. How do agencies change their minds? o Rules have precedence over adjudication: Arizona Grocery Principle—an agency is bound to adhere to existing rules when adjudicating and may not make ad hoc exceptions or departures. o Can always change rules through rulemaking but cannot appeal a rule in an adjudication (*unless “rule” established by adjudication, then can change it through another adjudication). o Agencies can choose to do things that they are not required to do. o Stare decisis is no more an inexorable demand for agencies than for article III courts. o Due Process requires an explanation for new policy and deviations from past decisions. DUE PROCESS HEARING RIGHTS DPC not relevant when agency acts as legislature only when adjudicating. Cong. could set up rulemaking however it wants. o DPC only applies to life, liberty, property. o If there is no adequate post-deprivation remedy, then likely entitled to a hearing. Bailey v. Richardson (1951) o Fired, requested administrative hearing, hearing was held, Bailey testified and presented other witnesses. Same day letter was sent to her saying that there were reasonable grounds for believing she was disloyal to gov. of U.S. o Dismissed from gov. employment. o Issue = whether DPC of 5th A requires that Bailey be afforded a hearing of the quasi judicial type. DPC does not apply to holding of gov. office (not “property” nor liberty nor life). Job is privilege not a right! Gov. can take away benefits without triggering constitutional limits. o Holding: no such hearing right exists here. Cafeteria Workers v. McElroy (1961) o Invokes right v. privilege distinction (don’t care about life, liberty, property), evaluates “grievous loss.” o Short order cook on naval base, security clearance revoked. o Issue = whether denial of employment violated DPC. 5th A does not require a trial-type hearing in every conceivable case of gov. impairment of private interest. o Holding: no violation. *Changes to membership of Court moving away from right v. privilege distinction. 40 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 - - - - North American Cold Storage Co. v. Chicago (1908) o Ordinance prohibited cold storage houses from storing food unfit for human consumption, warehouse applied for injunction prohibiting the stoppage of deliveries and threatened destruction. o Issue = when do you get a hearing? o Holding: DPC not denied to owner—provision of hearing is not necessary. Note: issue of timing of hearing: pre-termination hearing imposes a greater cost on gov. Goldberg v. Kelly (1970) o NYC residents received aid through fed. assisted programs, benefits were going to be terminated without prior notice and hearing. o Issue = whether DPC requires that recipients be afforded an evidentiary hearing before termination of benefits? (and what “process” is due) *again a question of TIMING of hearing! The extent to which procedural due process must be afforded to the recipient is influenced by the extent to which he may be condemned to suffer “grievous loss.” o Holding: Pre-termination hearing is required. (when welfare is discontinued, only a pretermination evidentiary hearing will provide recipient with procedural DP) Does not need to be full hearing, i.e. Art. III judges. Get notice, oral argument, cross-examination, impartial decision-maker (looks like a quasi-judicial trial). Board of Regents of State Colleges v. Roth (1972) (*the template going forward— FOUNDATIONAL CASE) o *2 previous approaches rejected: rights v. privileges, grievous loss. o This case separates out liberty and property. Makes grievous loss relevant only to question of how much process if process applies. First need to answer threshold question: does DPC kick in at all? (no longer focused only on weight of interest i.e. Goldberg). o Roth hired for 1 year term at Wisc. State U., fired after 1 year, filed suit claimed that University’s failure to give him reasons/opportunity for hearing violated DPC. o Issue = whether DP was required? To determine whether DP applies in the first place: look not to the “weight” but to the nature of the interest at stake—look to see if interest is within the 14th A’s protection of liberty and property. Here, respondent’s property interest in employment was created and defined by the terms of his appointment (no interest in re-employment). o Holding: respondent did not show that he had been deprived of liberty or property (no DP required). Liberty v. Property: Liberty rests on constitutional bottom—essential to orderly pursuit of happiness by free men. Property—doesn’t rest on constitutional bottom, comes from existing rules under state law. (a creature of state law!) Ask whether you have a legitimate claim of entitlement? State statutes, contracts. Perry v. Sindermann (1972) (*companion case to Roth but comes out differently!) o Teacher employed in TX state college system for 10 years with 1year contracts, no formal tenure system. o Contract not renewed. o Holding: teacher entitled to a hearing. Informal system of tenure gave him a property interest in continued employment. 41 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 - - - - - - Respondent must be given an opportunity to prove the legitimacy of his claim of such entitlement in light of the policies and practices of the institution. Bishop v. Wood o NC case—policeman fired, state law says police are employees at will so no property interest in employment. o Holding: no DP issue, if state fires without a reason no claim available. *State gov. has a significant amount of control whether you will ever have the amount of property interest to satisfy the threshold. Arnett v. Kennedy (1974) o Kennedy, civil service employee, discharged for recklessly accusing superior of bribery. Informed of charged and afforded hearing after dismissal. o Did not respond to opportunity for hearing, instead asserted proceedings unlawful because he had right to pre-termination trial-type hearing. o Holding: purpose of hearing in this case is to provide the person with an opportunity to clear his name. Hearing afforded by administrative appeal procedures after actual dismissal is a sufficient compliance with the requirements of due process. Must take the “bitter with the sweet” entitlement wrapped up with process, you have to take both, even though process might be less than what ordinarily might be constitutionally required. *“Bitter with sweet” is no longer good law, squarely rejected by Loudermill. Cleveland Board of Education v. Loudermill (1985) o Rejects “bitter with sweet” principle! Due process clause provides that certain substantive rights—life, liberty, property— cannot be deprived except pursuant to CONSTITUTIONALLY adequate procedures. While legislature may elect not to confer a property interest in public employment, it may not constitutionally authorize the deprivation of such an interest once conferred, without appropriate procedural safeguards. *A way around constitutional DP: If you do not want to give full constitutional protection, then case it not as a property interest, limit the interest! (don’t trigger procedural DP in the first place). Wisconsin v. Constantineau o Drunk being prevented from buying alcohol at liquor stores. o “Where a person’s good name, reputation, honor, or integrity is at stake because of what gov. is doing to him, notice and opportunity be heard is essential.” Paul v. Davis o Put on a list of known shoplifters. o Comes out opposite of Constantineau even though still about reputation! In above case there was a liberty interest of being prevented from buying alcohol. o No DP protections before deprivation if all that is at stake is reputation. Harm to reputation standing alone will not entitle you to anything. o *After this case: reputation alone is never enough of a liberty interest to guarantee DP protection. Cases involving prisoners: o Meachum v. Fano (1976) Conviction has sufficiently extinguished the D’s liberty interest to empower state to confine him in any of its prisons. That life in one prison is much more disagreeable than in another does not in itself signify that a 14thA liberty interest is implicated. o Sandin v. Conner (1995) 42 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 - - - Prisoner in max. security prison sentenced to solitary confinement after disciplinary hearing. Denied opportunity to call prison staff as witnesses. Holding: no protected liberty interest. Not only must there be an entitlement but there must be an atypical significant deprivation. (Based on what is atypical for prisons) *This is specific to prisoners! Does not apply outside bounds of prison. Mathews v. Eldridge (1976) (all of the above cases have been about whether or not you have a DP interest…now a question of how much!) *This case is the template for how much DP o Gov. conceded the question of whether there was DP, now the issue is… o Issue = whether DPC requires that PRIOR to termination of Social Security disability benefit payments the recipient be afforded an opportunity for an evidentiary hearing. (even though statute provides for hearing after termination) Consideration of 3 Factors: 1) private interest affected by official action; 2) risk of erroneous deprivation; 3) government’s interest, fiscal and administrative burdens (and going to defer to gov. on this) ONLY apply once you have crossed legalistic threshold. *Court does not say HOW to weigh, just gives factors. HERE: 1) disabled worker’s need is less than welfare recipients in Goldberg; 2) value of oral hearing is less in this context than in Goldberg, medical sources here are more effectively communicated through written documents; 3) public interest: costs and administrative burden not insubstantial. o Holding: evidentiary hearing is NOT required prior to termination of disability benefits. Present procedures comport with DP. *Note: balancing test looks like cost-benefit analysis. Formula = value of additional procedures x interest of claimant > increased burden on government. But what about dignitary interest that can’t be quantified? There are no obvious places for these kinds of intangibles. Walters v. National Association of Radiation Survivors (1985) o Veterans benefit program, veterans appearing in front of board can retain attorney but can only pay $10. o Issue = whether this fee limitation is a violation of due process right (to liberty). Under Mathews v. Eldridge great weight must be accorded to gov. interest. Marginal gains from affording an additional procedural safeguard often may be outweighed by the societal cost of providing such a safeguard. o Holding: DP not violated, process which is sufficient for the large majority of a group of claims is by constitutional definitions sufficient for all of them. Post-deprivation remedies as substitute for pre-deprivation agency hearings: o Extent of post-deprivation procedures and remedies are relevant to Mathews v. Eldridge test under this test you may not get anything even if you have an identified interest. o Ingraham v. White (1977) Ps had been paddled at school, without prior notice or opportunity for hearing. Issue = whether failure to afford a hearing prior to paddling violated due process. Liberty interest = interest in not physically retraining your body (constitutional arguments, no positive state law that gives you that interest). Requirement of a hearing would burden use of corporal punishment as disciplinary measure. Holding: DPC does not require notice and hearing prior to imposition of corporal punishment in public schools as that practice is authorized/limited by common law. 43 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 VIII. - Gov’s interest in having paddling is so strong and post-deprivation procedures could grant some relieve and make you whole if excessive punishment is found. Also court finds it unlikely that there will be erroneous paddling because this punishment is usually reserved for actions teacher saw. AVAILABILITY AND TIMING OF JUDICIAL REVIEW Reviewability o Federal courts are not courts of general jurisdiction. Often sovereign immunity is a huge roadblock to suit. o § 702 = Right of Review allows you to bring a claim in combination with federal jurisdiction statute (but still a gap-filler, if there is a more specific statute, that controls) o § 703 = Form and Venue of Proceeding o § 704 = Actions Reviewable Agency action made reviewable by statute and final agency action for which there is no other adequate remedy in a court are subject to judicial review o Specific statutory review = comes from right to review under specific statutes begins with organic act. o American School of Magnetic Healing v. McAnnulty (1902) P ran mail-order healing business. Postmaster stopped letters with payments from going to P. Congressional statute gives P this authority upon evidence satisfactory to him that party is engaged in fraud. Issue = whether P has remedy in court. Holding: injunction to prohibit further withholding by Postmaster. Court assumes you have a right to bring a lawsuit if you are hurt through an unlawful action. Didn’t focus on whether there was a statutory cause of action. o Switchmen’s Union v. National Mediation Board (1943) Opposite of above case! Brotherhood sought to represent all yardmen of rail line, Switchmen contended that yardmen were permitted to vote for separate representatives. Mediation Board decided dispute, said yardmen were participants in the election. Switchmen sought to have decision cancelled. Issue = whether judicial review was available under the statute. When Congress has not expressly authorized judicial review, the type of problem involved and the history of the statute in question become highly relevant in determining whether judicial review may be nonetheless supplied. Here, Cong. took pains to protect Mediation Board, if it had wanted to implicate federal judiciary it would have. Holding: no power to review. Statute does not explicitly preclude review but court finds preclusion by omission. o Preclusion under the APA (§ 701) Two preclusion options: § 701(a)(1) statutes preclude judicial review (i.e. organic statutes); § 701(a)(2) agency action is committed to agency discretion by law. § 701(a)(1) statutes preclude judicial review: express preclusion and implicit preclusion. Express contravenes presumption of judicial review (Abbott Labs) 44 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 1. 2. 1. 2. 1. 2. 1. 1. Judicial review of a final agency action by an aggrieved person will not be cut off unless there is a persuasive reason to believe that such was the purpose of Congress. Implicit not obvious what the source of law is for this presumption (not in the APA or Art. III) Johnson v. Robison (1974) (EXPLICIT) P, conscientious objector, tried to access veterans’ benefits, denied because only for veterans of military service. Challenged Congress’s creation of statutory class limiting access. Statute at issue has no explicit provision that bars judicial consideration of constitutional claims. LH indicates no-review. Holding: challenge to statute IS allowed despite how preclusive statute looks. Seize on “administration” of statute, agency doesn’t administer the constitution so can get around preclusion in statute itself. Court does not answer question of whether Congress can preclude constitutional claims (we know Cong. can preclude statutory claims). Traynor v. Turnage (1988) Veterans brought a claim about being denied educational benefits because they were alcoholics. Holding: no bar to review even though a “no review statute.” Because “no review” statute insulated from review decisions of law and fact under any law administered under Veterans’ Administration. This case was about whether the law was valid in light of a subsequent statute whose enforcement is not within the exclusive domain of the Veteran’s administration. Pretty strong presumption here! But explicit preclusions read V narrowly. Block v. Community Nutrition Institute (1984) (IMPLICIT) (note: somewhat of an outlier case) Agricultural Marketing Agreement Act allow Sec. of Agriculture to set price for milk handlers to pay producers for their milk. Consumers challenged decision that higher price applied to reconstituted milk. Issue = whether judicial review of administrative decision was available. (about who can sue) Court says buyers are not relevant to the pricing scheme. Congress made the act with handlers and producers in mind—this was a deal cut among them. Omission indicates Cong. intended to foreclose participation by consumers. Holding: implied preclusion (cannot review, no clear statutory language like in Johnson v. Robison). Block is good law although hard to find similar examples, has not been extended at all. Bowen v. Michigan Academy of Family Physicians (1986) Association of family physicians challenged regulation of Sec. of Health setting higher Medicare reimbursement levels for board v. non-board certified physicians. Issue = whether decision of agency can be reviewed. Under statute, individuals given insufficient payment are afforded opportunity for hearing, statute does not speak to challenges mounted against 45 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 method by which such amounts are to be determined (which is the issue here). 2. LH indicates that Congress did not preclude review of the method, not a minor matter at risk of clogging up court system. Holding: presumption of judicial review has not been surmounted. (judicial review allowed, references strong presumption Abbott Labs) How do you square Block and Bowen? Not in direct conflict! 1. In Bowen question is would anyone have right to sue? 2. In Block question is who gets to sue? Sackett v. EPA (2012) Under CWA, EPA found Sacketts had discharged fill material onto wetland without a permit. Sacketts didn’t think their property was subject to act, asked for a hearing, denied. Holding: compliance order was “final” and reviewable. 1. Court emphasizes presumption of reviewability (Scalia finds it in the APA although it must be in more than this because otherwise it would be a battle of statutes, i.e. organic v. APA). Nothing in CWA expressly precludes judicial review (and CWA afforded a review only if EPA sued for compliance this was not enough for court). § 701(a)(2) agency action committed to agency discretion by law (Second Exception to Reviewability!) Note: § 706(2)(a) “hold unlawful and set aside agency action, findings, and conclusions found to be—arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law.” also talks about agency discretion! Two big questions about reviewability? What does 701(a)(2) add to 701(a)(1) and how do we square (a)(2) discretion with 706 discretion? Heckler v. Chaney (1985) (applying “No law to apply”) Residents of OK and TX sentenced to death, petitioned FDA claimed drugs being used were not approved for this use. Requested FDA take investigatory and enforcement action. FDA commissioner refused, said could decline to exercise jurisdiction in this area. Issue = extent to which a decision of an administrative agency to exercise its “discretion” not to undertake certain enforcement actions is subject to judicial review under the APA. 1. 701(a)(1) applies when Congress has expressed an intent to preclude judicial review. 2. 701(a)(2) applies where Congress has not affirmatively precluded review, review is not to be had if the statute is drawn so that a court would have no meaningful standard against which to judge agency’s exercise of discretion. 3. Avoids conflict with 706 “abuse of discretion” because if no judicially manageable standard available for judging how and when agency should exercise its discretion then it is impossible to evaluate agency action for abuse of discretion. 4. When agency refuses to act (no enforcement), presumption that judicial review is not available. BUT presumption can be rebutted where the substantive statute has provided guidelines for the agency to follow in exercising its enforcement powers. 46 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 1. 2. 1. 2. 1. 2. 3. 4. Holding: Nothing in statute to rebut presumption of no reviewability (so NO review is available). *Note: in some situations (not common) a Court will lack power to invalidate agency action that is unlawful! Some situations where an agency has abused its discretion but it has discretion to do so, so nothing can be done about it. (Cong. has just given ENORMOUS discretion to agency). How do we define/identify these situations? Overton Park: NO LAW TO APPLY Functional factors: will this interfere with agency ability to carry out statutory mandates? a. No metric/standard to say you abused your discretion. b. When authority given to agency is SO broad that there is no judicially manageable standard to say that you broke the rule. c. A court cannot tell you how to prioritize your resources, agencies get to engage in their own resource allocation. d. Decision to enforce is more oppressive than decision not to enforce this explains the difference in the presumptions of reviewability. Norton v. Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance (2004) *How is this different than above case? obligation here to take some kind of action (in some situations agency is being told to do something specifically) Issue = whether the authority of a federal court under the APA to “compel agency action unlawfully withheld or unreasonably delayed” (706) extends to the review of the US Bureau of Land Management’s stewardship of public lands under certain statutes. Act had policy in favor of retaining public lands for multiple use management, use of off-road vehicles had negative enviro consequences. Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance filed action seeking injunctive relief for failure to protect public lands from off-road vehicles. Holding: no judicial action available. Why? Under 702 right to review if suffering legal wrong because of agency action. Agency action is defined to include the whole or part of an agency rule, order, license, sanction… All of these categories are discrete agency actions. Failure to act and denial are not the same thing! Failure to act is limited to a discrete action. But only agency action that can be compelled is that which agency is legally required to do (706 “unlawfully withheld”). THEREFORE, a claim under 706 can proceed ONLY where a P asserts that an agency failed to take a discrete action it was required to take. a. The more discrete the action the more likely to can be reviewed. b. Ex: of a discrete action : regulate all BPA levels in water bottles, versus regulate in the public interest is NOT a discrete action. HERE, Statute leaves BLM a great deal of discretion in deciding how to achieve mandatory goal of protecting wilderness does not mandate with clarity necessary to support judicial action. *Two separate issues in these cases: Is there any law to apply? Review of “agency inaction?” 47 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o 1. Failure to act = inaction presumption now law to apply and nothing to review 2. Denial = an action reviewability Webster v. Doe (1988) CIA agent fired for being gay, claims constitutional right not be fired and statutory right. But statute allows for discretion by CIA director to terminate employees. 1. Agency employees may be fired whenever the Director shall deem such termination necessary or advisable in the interest of the United States. Issue = whether and to what extent termination decisions of Director are judicially reviewable? 1. This is not about some complicated statutory scheme that you were left out of (implicit preclusion), this is an incredibly broad grant of discretion to the Director/agency. Holding: statute precludes statutory review (because committed to agency discretion by law (701(a)(2)). Constitutional claims were reviewable because closing off of such review may be unconstitutional. Dissent (Scalia): 1. “Now law to apply” is wrong, there is always some law to apply (common law review of agency action). No non-delegation problem, because it’s a broad grant of power in a very narrow scope BUT, the Constitutional claims CAN go forward: 1. This is a question about who gets to be the ultimate decider of what is Constitutional – Congress or the courts? Nothing says it necessarily has to be the courts, but we inherently believe that courts should be able to review Constitutional claims. *Case arose in national security context but has been cited outside of it! If you give agency “untrammeled” discretion then no law to apply. Reviewability at war: Hamdi v. Rumseld (2004) Although Congress had authorized the detention of enemy combatants in the circumstances of the case, due process requires that a citizen held in the US as an enemy be given a meaningful opportunity to contest the factual basis for that detention. Cites to Mathews v. Eldridge balancing test to balance serious competing interests. Reviewability even during wartime! Preclusion Summary Preclusion under § 701(a)(1) “statutes preclude judicial review.” Express: does a statute clearly preclude review? With regard to constitutional claims does it clearly intend to preclude them? Implicit: absent explicit preclusive statutory language, is judicial review for these plaintiffs plainly inconsistent with the statutory structure or does that structure otherwise indicate a congressional intent not to allow these plaintiffs to sue? Preclusion under § 701(a)(2) “agency action is committed to agency discretion by law.” 48 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 IX. - - If there is no explicit or implicit preclusion of review should review nonetheless be denied on the ground that there is no law, in the relevant statute or anywhere else, by which to assess the plaintiffs’ particular claim? STANDING In addition to establishing that administrative action is reviewable, litigant must also have “standing.” Standing requirements limit who is able to get in the courthouse door. Organic statutes sometimes delineate this, sometimes they are silent. “Public action” idea that any citizen can sue gov. for any law violation, some states allow this but GENERALLY courts don’t accept this claim, must prove more. o Only exception = Flast v. Cohen (1968): court grants standing to taxpayers to challenge as a violation of establishment cause federal statute authorizing federal grants for instruction and teaching material in religious schools. Established nexus between taxpayer status and statute challenged and nexus between taxpayer status and constitutional provision invoked. *Note: this case has not been generative, has been cut back on itself. “Zone-of-interest” test: o Prudential/statutory standing as distinct from constitutional standing. o But Lexmark case (supplement) disclaims idea of “prudential standing” now just ask generally, whether one has a right to sue by interpreting what Congress has done and what the statute says (just common statutory interpretation). Note: there may still be references to “prudential standing” but generally this term is out. o ADAPSO v. Camp (1970) Petitioners sell data processing services, challenge ruling by Comptroller that national banks can make data processing services available to other banks and their customers. Competition with national banks might entail future losses for petitioner. Issue = whether petitioner has standing (whether P alleges that challenged action has caused him injury in fact economic or otherwise). Little question that ADAPSO suffered injury in fact. Question of standing concerns the interest sought to be protected by the complainant and whether it is arguably within the zone of interests to be protected or regulated by statute. § 4 of Bank Services Corporation Act brings competitor within zone of interest protected by it. Holding: petitioners HAVE STANDING to sue. *Note: no one ends up liking this opinion! Some think it goes too fair some say not enough—does not do much to flesh out zone-of-interest test. o Clarke v. Securities Industry Association (1987) (clarifies test!) Ps, association of securities dealers, sued comptroller claiming he exceeded authority in permitting national banks to open offices that sold “discount brokerage services.” Issue = whether Ps were in zone-of-interest and had standing to sue. In cases where P is not itself the subject of the contested regulatory action, the zone-of-interest test denies a right of review if P’s interests are so marginally related to or inconsistent with the purposes implicit in the statute that it cannot reasonably be assumed that Congress intended to permit the suit. 49 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o o o This is kind of like a reasonable interest about what Congress was considering when it wrote the statute: i.e. who was around the lobbying table. Don’t have to show that Congress explicitly intended to benefit you, just show interests that are more than marginally related. Holding: respondent was a proper party to bring the suit. No congressional intent to preclude review for this group. Air Courier Conference v. American Postal Workers Union (1991) *First case EVER where P lost under zone-of-interests test! (this was not generative though). Private Express Statutes grants postal service monopoly over carriage of latters, but allows service to suspend its restrictions on particular mail route when “public interest requires.” Union challenged service’s suspension of its monopoly to allow private couriers to deliver some types of mail. Holding: union lacked standing, although possible injury to employment of postal workers, did not fall within zone-of-interest protected by the statute. National Credit Union Administration v. First National Bank & Trust Co. (1998) FCUA authorizes chartering of credit unions, provides that federal credit unions can only offer banking services to members. Section 109 restrict membership in unions to those groups having a “common bond of occupation,” NCAU reversed policy, interpreted common bond requirement to apply to employer groups within multigroup credit union (thus expands reach of credit union). Respondent banks brought action, said interpretation contrary to the law. Issue = do respondents have standing? (whether interest sought to be protected is within zone-of-interest of statute) Finds there is an interest, banks have a market interest to be protected in limiting markets that credit unions can serve (banks lobbied to have this language put in statute). Banks are competitors of federal credit unions. Do NOT need to ask whether in enacting the statutory provision at issue, Congress specifically intended to benefit the P, instead FIRST discern the interests arguably to be protected, THEN inquire whether the P’s interests affected by the agency action in question are among them. Holding: respondents DO have standing. Dissent (O’Connor): All but eviscerate zone-of-interest test with this holding. Banks are being injured not in a way that is protected by the act (their injury is about loss of customers), just being a competitor is not enough (court’s approach is too wide)! In previous cases Congress had enacted anti-competition limitation in statute, this is not the case here. Potawatomi Indians v. Patchak (2012) Indian Reorganization Act, about tribal lands. Indian group sought to build a casino on their land, neighbor filed suit alleging that casino would destroy piece and quiet of community. Holding: court found that neighbors can sue even though they are not mentioned in statute because their interests are within zone-of-interest. They were in the “background” of the statute, not just bystanders. Requirement was just a relation to the acquisition or use of territory for Indian tribes, Patchak’s suit concerned that acquisition and use of territory. 50 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o - Block v. Community Nutrition Was really a case about standing! Supreme Court never reached this issue though because they said separate from standing there was also a prelusion hurdle (preclusion of review). o When will there ever be an injury in fact but outside zone-of-interest? Military changes what ammo it uses, this impacts specific hunters that now have to pay more for that ammo. Constitutional Standing o Even if you satisfy zone-of-interests test, must satisfy constitutional “case and controversy” language. o 3 Elements of Standing as a Constitutional Matter: Injury in fact: “concrete and particularized” and “actual and imminent” FACTUAL QUESTION Causal connection: traceable to challenged action Injury must be redressable *Note this is not a matter of statutory construction Congress cannot authorize suits if above 3 elements aren’t met. Not a good argument to say: If I don’t have standing to sue then no one has standing to sue (because sometimes no one does have standing to sue). o Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife (1992) Endangered Species Act, Sec. revised rule to limit geographical scope to US wildlife conservation, Defenders sued claiming revised rule misinterpreted the statute. Issue = whether Defenders have standing to sue? Party invoking federal jurisdiction bears the burden of establishing the elements of standing. When P is not himself the object of gov. action or inaction, standing is not precluded but it is ordinarily substantially more difficult to establish. Here, respondents claim to injury is increase in extinction in animals abroad and its members not being able to travel to see these animals. Holding: respondents lack standing. Affidavits of Wildlife members not enough, contain no facts showing how damage to species will produce “imminent” injury. Also failed to show how injury could be redressed by victory on merits. A P raising only a generally available grievance about the gov. does not state an Art. III case or controversy. Also no redressability—case against Sec. of Interior, even if Sec. changed its decision, wouldn’t give you what you want because funding agencies are not bound to that decision and projects might go forward anyway. o Sierra Club v. Morton (1972) US Forest Service approved proposal from Disney to build ski resort in Mineral King Valley, area of “great natural beauty” in Sierra Nevada Mountains. Sierra Club brought suit as a membership corporation with a special interest in conservation. Issue = whether Sierra Club has alleged an injury in fact to gain standing to sue. Injury alleged says that development would destroy the scenery, natural, and historic objects and wildlife of the park. (didn’t allege injuries to its members) A party itself must have been injured! (cannot allege injury to environment) Holding: no standing to sue. 51 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o o o Sierra Club never actually alleged that its members used the valley—why? Wanted the bigger win to be able to just bring cases on behalf of the environment (but this is what they lost on—court didn’t buy this argument). United States v. SCRAP (1973) Environmental groups challenged as violation of NEPA, ICC’s failure to prepare environmental impact statement on increase in rates by railroads. Group said that increase in rates would discourage production of recycled goods. P said their members would suffer harm by being exposed to increased pollution and increased litter in forests. Holding: environmental interests that SCRAP sought to protect were clearly within the zone of interest protected by NEPA Unlike Sierra Club in Morton, SCRAP had sufficiently alleged “specific injury” to its members in form of harm to their use and enjoyment of natural environment in DC area. Nexus here is attenuated but court avoids this because the motion is just to dismiss not sum. judgment for SCRAP. Friends of the Earth v. Laidlaw Environmental Services (2000) Laidlaw got permit to pollute under CWA, polluted too much. FOE filed citizen suit against Laidlaw, seeking declaratory and injunctive relief + civil penalties. Issue = standing Relevant showing for purposes of Art. III standing is not injury to environment but injury to P. Ps established this injury with their affidavits (not getting to use the environment like the wanted to). must be reasonable basis for concern in not using enviro. Compare with Clapper v. Amnesty International (2013) (supplement) 1. References Laidlaw, where fears were reasonable, fears here not reasonable (although post-Snowden doesn’t seem quite as tenuous). 2. Challenge to Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, which allowed Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court to authorize without probable cause surveillance of people outside US. 3. Here, maybe the government doesn’t care a fig about you at all – you might be just imagining things that there is no reason to believe is going to actually happen definitely not “certainly impending” 4. Court found no standing 5. Still “good law” in cases where there is all kinds of uncertainty (when we can’t say with certainty that there is any injury as to you). In comparison to Lujan, proximity helps here, the people live right next to the pollution, whereas in Lujan had to show they were going back to Sri Lanka. Civil penalties found to have deterrent effect (redressability). Holding: standing components satisfied. Dissent (Scalia): Must show objective harm to the environment and subjective harm to yourself. (In response to this majority says that this raises standing hurdle too high, don’t even have to show this much to win on the merits). Generalized remedy that deters all future unlawful activity against all persons cannot satisfy the remediation requirement. Coalition for Responsible Regulation v. EPA (2013 D.C. Cir. case) Industry didn’t have standing even as an entity subject to regulation because regulation challenged actually lessened their injuries (they had challenged it 52 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o o o nonetheless because wanted regulation thrown out so that Congress would legislate and that would likely be even better for them. Court says: too speculative, supposition that Cong. will be compelled to act better with better legislation is too tenuous. Simon v. Eastern Kentucky Welfare Rights Organization (1976) Ps, indigents, and orgs representing them challenged revenue ruling by IRS modifying responsibilities of nonprofit hospitals. Hospitals could qualify as nonprofits even if they didn’t accept indigent patients who couldn’t pay. Ps alleged specific incidents of deprivation where they were denied medical services. Claimed IRS ruling encouraged such denials. Issue = whether individual respondents have established an injury in fact. Injury at hands of hospital is insufficient because hospital is not the defendant (Ds are dept. of treasury) and injury cannot result from independent action of some third party not before the court (here, hospitals). Purely speculative whether denials of services can be traced back to IRS. (too little information to be confident about connection between causal link not direct enough). Holding: no standing, complaint dismissed. Massachusetts v. EPA (2007) State and enviro group challenged EPA denial of rulemaking petition. Issue = whether petitioners (MA) have standing. Harm here is coastline being imperiled by global warming. Emphasizes special status of MA as a state (“special solicitude”), but also goes through nexus and redressability argument. Weight given to status of MA is hard to tell because most of analysis is just ordinary standing. Not dispositive that developing countries like China and India are poised to increase GHGs, EPA still has duty to stake steps to slow or reduce climate change. Holding: have alleged injury and remedy sufficient for standing. Dissent (Roberts): Climate change is cumulative, most emissions not from US anyway, doesn’t believe regulation will fix anything. Bigger question: what is the role of the courts? Is this for the courts to answer or policy for exec. or legislative branch to work through? What do we do when there are 1000 different things that can influence a global trend? This is the choice in this case! *Causal nexus & redressability: not purely factual questions, also underlying question of law—if redressed a tiny is this enough? Here, a tiny amount is enough (Court finds don’t have to be sure that there still won’t be other causes of global warming). Steel Company v. Citizens for a Better Environment (1998) Private enforcement action under citizen-suit provision, sued manufacturing company for violations of EPCRA which required it to make certain filing deadlines and submit hazardous chemical inventory and toxic chemical release forms. Respondents said they had a right to know about toxic chemical releases, interest in protecting enviro and health of members. Issue = whether EPCRA authorizes suits for past violations and whether P has standing to sue over those past violations. 53 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 - - - X. Complaint fails redressability: civil penalty, but fine goes to Dept. of Treasury not citizens (doesn’t redress your injury need money that goes to you and cost of litigation is not sufficient in this situation). No allegation of ongoing injury (past failures rectified), nothing to deter with penalties. Generalized interest in deterrence is not enough. Don’t have the right stake in the litigation so don’t get in the door. Holding: complaint dismissed, no standing. *Case contrasts Laidlaw where court found that fines will affect future actions (although Scalia says that this is too speculative to have penalty for past conduct). Majority in Laidlaw thinks that a D hit once in the pocketbook will think twice about polluting again (this is just the court’s idea—not citing to anything). How do you make a statute have general standing? o Make any penalty payments available to individual Ps—this give a person redressability. o Could try to go farther—every American has a property interest in endangered species (likely this would never happen). o Citizen suit provision: why do we want this if DOJ could use enforcement mechanisms? Citizens will pick up what gov. couldn’t prioritize, want individuals to do things beyond gov. enforcement priorities. More consistency if citizens always have that power, not affected by political winds. Threat of potential litigation might make agencies more diligent. *Note Scalia doesn’t like citizen suits: this is an Art. II argument, separation of powers issue—give citizens power that is ordinarily given to Exec. branch (President has “take care” authority). o Courts have held that qui tam relators have Art. III standing, not addressed whether they have violated Art. II. (qui tam = civil whistleblower lawsuit, get rewards if qui tam case recovers money from gov.) Summary: o In some situations no one gets to sue o In other situations only regulated parties get to sue (Asymmetric against those who want more regulation, unfair one way street?) o Limits on Congress’s power: Cong. cannot let just anyone sue freely (although citizen suits can open the door). Court’s control. Although the more we allow things like citizen suits, the more Congress is opening the door for suits and diminishing agency control over the enforcement priorities that they want to have. To bring a cause of action in administrative law: o Cause of action APA o Waiver of sovereign immunity APA o Standing show prudential standing through statutory interpretation—did Congress in general intend to include your interests (zone of interest)? AND “case and controversy”— constitutional requirement: injury in fact, causation, redressability. a. *Injury in fact, causation, and redressability are judge-made interpretations of “case and controversy.” o Remember! There may be some government actions that NO ONE will be able to challenge because simply no standing—not a constitutional issue because limited by provisions of Art. III (of the Constitution) not congress. RIPENESS, FINALITY, AND EXHAUSATION 54 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 - - - Standing is about whether you get to sue, ripeness, finality, and exhaustion are about when you can sue. Finality: only one in the APA! Focuses on agency itself, 1) consummation of the process of decisionmaking. 2) Legal consequences must follow. if these two factors are not present then cannot challenged EVEN if you have been injury. (See Sackett, agency had come to end of a process,). If not final, not reviewable under APA. o FTC v. Standard Oil Co. of California (1980) (interlocutory review) (standard finality case!) FTC issued complaint against oil companies, they moved to dismiss complaint asserting that it had been filed as a result of political pressure by Congress. Commission denied motion, respondents sought judicial review of refusal to dismiss. Unlike in Abbott, no practical or legal effect on oil companies if no review allowed. In fact, effect of judicial review is likely to interfere with proper function of agency and burden the courts. Holding: commission’s denial of motion to dismiss was not “final agency action” and was not presently subject to judicial review. o Franklin v. MA SEC’s decision was not final because sent report to president, cannot sue president because under the APA president is not an agency. Exhaustion: not in APA, what you have done—have you taken all the steps? o Argument is strongest when agency has not passed upon a question and is willing to consider it. o Myers v. Bethlehem Shipping Corp. (1938) *note: pre-APA case Act implemented, meant to diminish causes of labor disputes burdening interstate and foreign commerce. Complaint filed against Bethlehem for engaging in unfair labor practices, B filled bill in court to enjoin proceedings against it. Issue = whether court has jurisdiction to enjoin board hearing. No claim that such hearings were illegal or that B was not accorded opportunity to answer complaint. Cong. vested power in Board to prevent groups from engaging in unfair practices. Grant of such exclusive power is constitutional because act also provide for procedures before board and later review by court of appeals. Holding: Court without power to enjoin Board from holding hearing. Agency should have opportunity to correct its own mistakes, change its mind, so you don’t have to bother courts, avoids unnecessary litigation and piecemeal litigation (court of appeals can later hear all objections at once). *APA enacted in 1946, then 1993 first exhaustion case post-APA. Court finds no exhaustion requirement in APA, gets rid of Bethlehem common law notion of exhaustion. APA applies UNLESS trumped by another statute (organic act), so unless organic act includes exhaustion, no claim can be made. Ripeness: position of courts, are courts in a position to be able to decide the issue? o Abbott Laboratories v. Gardner (1967) Amendments to Food, Drug, Cosmetic Act required prescription drug manufacturers to print on labels the “established” name of the drug prominently as large as “proprietary” name of drug (generic v. trademarked brand name). Purpose was to encourage price competition among manufacturers. Done through APA rulemaking procedure notice-and-comment. Pharmaceutical Manufacturer’s Association brought injunction action in court (has not been any enforcement action yet, agency has only just promulgated rule). 55 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o o XI. - Issue = whether Cong. intended to forbid pre-enforcement review and whether issues were “ripe” for review. APA provides specifically for review of agency action made reviewable by statute, and also for review of final agency action for which there is no other adequate remedy in a court. final agency action + aggrieved person Only upon a clear and convincing evidence of contrary legislative intent should the courts restrict access to judicial review. Ripeness = 2 fold inquiry: 1) evaluate both the fitness for judicial decisions and 2) the hardship to parties of withholding court consideration. Fitness = concede this is a legal Q, no facts to develop and this final agency action (making rule). Hardship = direct effect, expensive compliance and non-compliance (fines). Holding: Pre-enforcement review is available, issues are ripe. Where the legal issue presented is fit for judicial resolution and where a regulation requires an immediate and significant change in the P’s conduct of their affairs with serious penalties attached to noncompliance, access to the courts under the APA and the Declaratory Judgment Act must be permitted absent a statutory bar or some other unusual circumstance. Gardner v. Toilet Goods (1967) Not ripe in the same way as Abbott Labs, court not so persuaded that hardship to parties is great. Regulations are final but even with final regulations, need to learn more about their implementation (goes to “fitness”—a lot of unresolved questions about what will happen when regulation implemented). Two different responses to Abbott Labs: Makes judicial review too easy (ossifying rulemaking, need to do more and more beforehand). Makes judicial review too hard, ripeness is made up, all § 704 requires is finality + legal wrong + no other remedy in court. *As a practical matter, ripeness is rarely a problem when it comes to preenforcement review. Note: Abbott Labs decided before Overton Park and State Farm—post these cases rulemaking looks different, threat of hard look review leads to a lot more detail in rulemaking process. Wouldn’t have as many unresolved questions as you do in Toilet Goods. Leads to pre-enforcement review being the norm today, also a lot of statutes authorize such review. Agencies don’t try to push ripeness challenges anymore. SUMMARY What are the hurdles to agency action? o Choices get complex quickly! o Rulemaking: time consuming, respond to every argument, take a hard look. Non-trivial chance of reversal of rulemaking! o If you choose adjudication instead…can also be time consuming! Informal adjudications aren’t binding. o Guidance documents, interpretive rules, policy statements cannot effect change in the law this way—cannot have legally binding effect. o Good cause (Exception to rulemaking)—time pressure, move quickly to get regulations out. 56 Admin Law Outline, Spring2022 o o o OIRA—check CBA, this check happens before you even get to court. Executive Orders—can reverse other Eos, but doesn’t get rid of regulations. If want to remove a regulation, need a whole new action! At some point, the last “check” comes from somewhere. It’s not always the courts, although for most things it is. 57