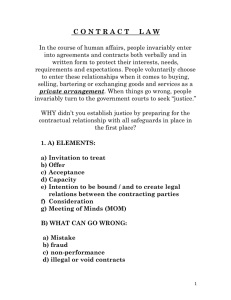

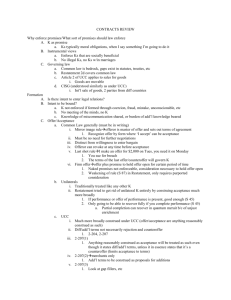

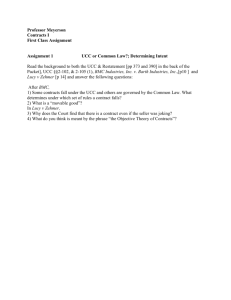

Contracts Spring 2017 - Johnson - Glen Dalakian II TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 2 FORMATION....................................................................................................................................................................... 3 I. MUTUAL ASSENT............................................................................................................................................................. 3 A. Offer and Acceptance in Bilateral Contracts .................................................................................................................... 4 B. Offer and Acceptance in Unilateral Contracts .................................................................................................................. 6 C. Postponed Bargaining: Agreement to Agree ................................................................................................................... 7 i. Good Faith Bargaining ...................................................................................................................................................... 8 II. CONSIDERATION ............................................................................................................................................................ 8 III. UCC FORMATION ......................................................................................................................................................... 10 A. Mutual Assent Under the UCC ....................................................................................................................................... 10 B. The “Battle of the Forms” .............................................................................................................................................. 11 C. CISG .............................................................................................................................................................................. 12 III. ELECTRONIC & LAYERED CONTRACTING ................................................................................................................... 13 IV. PROMISSORY ESTOPPEL ............................................................................................................................................ 13 A. Promises within the Family ............................................................................................................................................ 14 B. Charitable Subscriptions ................................................................................................................................................ 14 C. Promises in the Commercial Context ............................................................................................................................. 14 V. LIABILITY ABSENT ACCEPTANCE ................................................................................................................................. 15 A. Option Contracts ........................................................................................................................................................... 15 B. Reliance on Unaccepted Offers ...................................................................................................................................... 15 C. Statutory Limits on Revocation ..................................................................................................................................... 17 VI. RESTITUTION............................................................................................................................................................... 17 A. Restitution Absent a Promise ........................................................................................................................................ 17 B. Promissory Restitution .................................................................................................................................................. 18 VII. STATUTE OF FRAUDS ................................................................................................................................................. 19 A. Part Performance .......................................................................................................................................................... 20 B. Estoppel ........................................................................................................................................................................ 21 C. Statute of Frauds under UCC ......................................................................................................................................... 22 UCC § 2-201. Formal Requirements; Statute of Frauds. ...................................................................................................... 22 INTERPRETATION ........................................................................................................................................................... 23 VIII. PRINCIPLES OF INTERPRETATION ............................................................................................................................ 23 IX. PAROL EVIDENCE RULE .............................................................................................................................................. 24 X. IMPLIED TERMS ............................................................................................................................................................ 26 XI. GOOD FAITH ................................................................................................................................................................ 27 A. Requirements and Output Contracts ............................................................................................................................. 28 XII. WARRANTIES .............................................................................................................................................................. 28 AVOIDING ENFORCEMENT: BASKET OF CREEPY CASES ............................................................................................. 30 XIII. MINORITY & MENTAL INCAPACITY ........................................................................................................................... 30 A. Minority (Infancy) .......................................................................................................................................................... 30 B. Mental Incapacity .......................................................................................................................................................... 30 XIV. DURESS & UNDUE INFLUENCE ................................................................................................................................. 31 A. Duress ........................................................................................................................................................................... 31 B. Undue Influence ............................................................................................................................................................ 32 XV. MISREPRESENTATION & NONDISCLOSURE ............................................................................................................. 32 A. Misrepresentation ......................................................................................................................................................... 32 B. Nondisclosure (Silence) ................................................................................................................................................. 33 C. Fraud in the Execution ................................................................................................................................................... 34 XVI. UNCONSCIONABILITY ............................................................................................................................................... 35 XVII. PUBLIC POLICY ......................................................................................................................................................... 37 NONPERFORMANCE ....................................................................................................................................................... 37 XVIII. MISTAKE .................................................................................................................................................................. 37 A. Mutual Mistake .............................................................................................................................................................. 37 B. Unilateral Mistake.......................................................................................................................................................... 38 XIX. IMPOSSIBILITY, IMPRACTICABILITY, & FRUSTRATION ............................................................................................ 39 XX. MODIFICATION ........................................................................................................................................................... 40 XXI. EXPRESS CONDITIONS .............................................................................................................................................. 42 XXII. MATERIAL BREACH .................................................................................................................................................. 44 XXIII. REMEDIES FOR BREACH (DAMAGES) ..................................................................................................................... 45 1 INTRODUCTION Contract Law = Rules of Facilitation; “Get out and trade”, however you want. Consideration detriment Promissory Estoppel reliance Restitution unjust enrichment Contract: an exchange relationship created by oral or written agreement between two or more persons, containing at least one promise, and recognized in law as enforceable, reflecting several essential elements: 1. An oral or written agreement between two or more persons. a. Doesn’t require true agreement in a subjective sense (meeting of the minds). 2. An exchange relationship. a. A reciprocal relationship where each party gives up something and gets something. 3. At least one promise a. Some commitment to act or refrain from acting in a specified way at some future time. b. Express OR implied. 4. Enforceability. History of Contract Law Classical contract law (Williston) o Scientific, strictly objective approach o Positivism: stressed preeminence of legal rules o Harsh, formalistic, rooted in logic rather than experience o Rugged individualism; take care of yourself (even if illiterate) o Still prevails in many situations – often have to reconcile with different doctrines o Rules > people Contemporary/Modern contract law (Corbin) o Multidisciplinary approach (justice & equity) o Sociological jurisprudence; basic fairness; more forgiving process/methodology. o Law is made for man, man is not made for law. o Legal realism: dominant approach to the law- loose, flexible approach, challenges preeminence of rules. General standards such as “good faith” and “unconscionability” Recognizes impossibility of true objectivity o Economic analysis: primarily concerned with facilitation of exchanges on the free market Produced a swing back toward a more formalist view of contract law in late 20 th century. Emphasizes efficiency and reducing transaction costs. o Macneil: contracts should seek to preserve long term relationships (good faith/fair dealing) Structure of Contract Law 1. Formation o Offers & counteroffers; Promises; Form agreements 2. Interpretation o Obligations of each party o Conduct can be expressive of intent o Rights and duties required by law (implied terms) 3. Performance 4. Damages o Breaching contract is not a tortious “wrong” against a person. So no punitive damages Johnson’s Pyramid Express terms Course of performance Course of dealing Usage of trade General Inferences 2 FORMATION I. MUTUAL ASSENT “Mutual manifestations of assent” (never “meeting of the minds”) Allen v. Bissinger (1923) Facts: ICC reporter offered meeting minutes for sale. Bissinger requested them for money. Reporter accepted and provided the report. Not what Bissinger expected, so refused to pay. Rule: Mutual assent established. No fraud or misrepresentation; contract valid. Objective Theory of Contract (Test of Mutual Assent) Looks at conduct of parties from perspective of “reasonable person”, rather than attempting to examine party intentions. “Manifestation of mutual assent.” o Holmes: each party has notice that his words will be given a normal meaning and cannot complain if misunderstood. Judge parties by their actual conduct, not “secret intent”. o Learned Hand: “20 bishops” example (below); classic statement of the strict objectivist position. Duty to read. Subjective Theory of Contract Intention to be bound by the party creates a contract, not a party’s conduct, or reasonable outsider view. Requires “meeting of the minds”. Approaches to Contract Interpretation Holmes’ External approach: words understood by normal usage. Williston’s Objective theory: what reasonable person familiar with the circumstances (even a third party) would have guessed the terms were. Corbin’s Modified Objective approach: whose meaning controls the interpretation of the contract? And what is that party’s meaning? Restatement Second of Contracts: Did other party know first party held a different meaning for the terms? o If parties had different meanings, and didn’t know the other held a different meaning, then no mutual assent and no contract. Relational Contract Theory: Contract context changes when same parties exchange frequently; different than a one-off transaction. Second Restatement (§21): rejects subjective approach; law looks merely for sufficient expression of apparent commitment to perform. Ignores disparity in bargaining power. Ray v. Eurice Bros. (1952) Facts: Builder refused to build house based on new specifications he didn’t read because assumed contract based on original bid. Court enforced duty to read. Rule: Objective Theory: what would a reasonable person in the position of the parties think? o Learned Hand: busload of bishops saying you agreed is irrelevant. What matters is what reasonable observer, in that situation, believes you manifested by your action. Notes: Classical doctrine ignores imbalance in bargaining power; self-protection. Expectancy measure of damages makes you whole again. Skrbina v. Fleming Co. Facts: Duress; refuse employee benefits unless you sign. Rule: Absent creepy cases, he read the release and knew what he was doing. Classical doctrine. Notes: What if English was not his first language? Fraud no excuse; should seek held. 3 A. Offer and Acceptance in Bilateral Contracts “Offeror is the master of the offer” o But who is the offeror? What if there are negotiations or counter offers? Whose terms prevail? Offer: expression of the offeror’s fixed purpose requiring no further expression of assent on the offeror’s part. Acceptance: promise to perform induced by the offeror’s promise. o Agreement on terms only, NOT a meeting of the minds o Must be unequivocal and unqualified for a contract to be formed o Silence rarely amounts to acceptance. Qualified acceptance/Counteroffer: rejection of original offer coupled with new offer, unless expressed otherwise. Feldman v. Google (2007) Facts: Feldman signed click-wrap agreement for Google AdWords. Charged for fraudulent clicks. Rule: Agreement enforceable. Price terms existed with formula: practicable method of determining price. Mutual assent better than meeting of the minds. Specht case: No reasonable notice of contract terms for clickers; terms on separate page. Normile v. Miller (1985) Facts: After offer and counteroffer, seller sells to a third party. Rule: Mirror Image Rule: Acceptance must be a mirror image of the offer. Agreement means mutual assessment of deal are the same (meeting of the minds). Note: Sometimes seller could have obligations to more than one party, if you accept two offers for one piece of inventory. Revocation can happen when offeree hears of some behavior by offeror that changes the circumstances. If you have reasonable belief that offer is revoked, it is. Mirror image rule: offer and acceptance must be mirror images of each other/say the same thing. If not, and no performance, no contract. (CL rule; UCC abandons this rule.) Last shot rule: during offer-rejection-counteroffer cycle using forms, last document before performance is the one that controls. Revocation Time period may be specified in the offer. May be varied based on the specific culture. Offeror can revoke until acceptance, or offeree can reject. o Notice can be circumstantial or indirect. What Constitutes an Offer? Intent to enter into a bargain o Reflected by language and surrounding circumstances. Definiteness of terms o Must make clear the subject matter of the proposed bargain, the quantity involved, and the price. Lonergan v. Scolnick (1954) Facts: Exchange of letters over property listed in a newspaper. Offeror sold property to third-party during communications with original offeree. Rule: Invitation to bid, not an offer. There can be no contract unless the parties have mutually agreed upon some specific thing. First Restatement §25: All contingencies must be removed and intent to close the deal must be clear, based on circumstance/context. Requires expression of “fixed offer”. 4 Advertisements as Offers Traditional rule: ads are invitations to bid, NOT offers. To make an offer via an ad, you need to have expressed terms eliminating contingencies: “Three available, first come, first served.” o If ad isn’t an offer, rule may be abused with bait and switch. Izadi v. Machado Ford Inc. (1989) Facts: Ford ad notes trade-in value for any car, but with fine print Rule: Modern doctrine applied: ”It is time to hold men to their primary engagements to tell the truth and observe the law of common honesty and fair dealing.” / “Prominent thrust of the advertisement.” Where bait-and-switch is suspected, public policy justifies holding ad to be an offer despite seller’s true intentions. Secondary Rule (Williston): The test is not what the party making it thought it meant or intended it to mean, but what a reasonable person in the position of the parties would have thought it meant. o Bait and switch occurred – satisfies misleading ad claim. o Words have a “communal existence”. Jokes as Promises Low predictability: many elements and corresponding values Lucy v. Zehmer Facts: Offered farm for sale on napkin for $50k. Offeree signs it. Court enforces contract, and refuses to credit claim as a joke (drunk too – no doctrine of intoxication allowed). Rule: Court doesn’t want people screwing around with contract rules. Objective manifestations of assent. Note: Modern test: past dealings between parties made it reasonable for buyer to believe seller was serious. Leonard v. PepsiCo Facts: Harrier jet for Pepsi points and $700k. Rule: Commercial/ad was considered a “joke”. No reasonable viewer could have thought this serious. Notes: Maybe Pepsi did it on purpose knowing someone might sue and get publicity for Pepsi. Or the other products seemed more desirable next to this false offer. “Toy yoda” Case Facts: Winner of wings-selling competition wins new “toy yoda”. Rule: Looks like fraud. Ultimately restaurant loses & settles. How did the cruelty/nastiness of the joke leave us dissatisfied with the Willistonian approach? Note: What if employee induced to work extraordinarily hard, extra hours, to win the Toyota. Mailbox (Deposited Acceptance) Rule: Communication of Acceptance An acceptance MAY be effective as soon as dispatched (mailed/sent); default rule unless offeror expressly rejects it. Presupposes proper mailing. Based on practical need of offeree to have a firm basis for action in reliance on effectiveness of her acceptance once dispatched. Does NOT apply if acceptance follows a counteroffer or rejection. Revocation is effective upon communication. CISG – revocable offer cannot be revoked once an acceptance has been dispatched. BUT, must reach the offeror in a timely fashion; no “lost acceptances”. Restatement §63 rejects mailbox rule: acceptance valid upon receipt. Adhesion Contracts: boilerplate contracts; unconscionable. “take it or leave it” No choice (no alternative) Unchangeable (no negotiation) 5 Unequal bargaining power Option Contracts: offer remains locked in and offeree gives payment for that promise. B. Offer and Acceptance in Unilateral Contracts Bilateral contract: two promises made and agreed upon. Unilateral contract: one promise in exchange for performance; ability of person to perform is contingent/uncertain. Promise in exchange for performance; performance is consideration for promise and promise is consideration for performance. Lack mutuality; free to perform or not. Promisor bound once promise begins performance. o Ex: Find my cat; reward $100. Classical contract theory offered maximum protection to offeror, who isn’t bound until performance is received; for offeree, carries risks. o Under classical doctrine, part performance ≠ contract, no remedy. If traditional rules of revocation are applied to unilateral contracts, opportunities for abuse arise Abuse has resulted in adjustments honoring unilateral contracts so people aren’t afraid to trade. Restatement §32: if offer ambiguous, offeree can accept either by making return promise or by rendering performance if offeror will accept; pretty much forms a bilateral contract. Restatement §45: after part performance, offeror becomes bound; can’t revoke if full performance tendered under terms of contract (similar to concept of option contract). Reliance acts as substitute for consideration. (Corbinian) Cook v. Caldwell Banker/Frank Laiben Realty Co. (1998) Facts: Real estate agent works for Caldwell which offers bonus program. Agent achieves commission goals. D subsequently revokes original offer, saying you have to be here until certain date to receive the money. Rule: Used Restatement §45: substantial performance supplies consideration for contract formation. o [Corbin] Substantial performance: Once offeree has substantially performed, offer irrevocable. o [Restatement] In unilateral contract, part performance furnishes consideration. Reliance acts as substitute for consideration. Sateriale v. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Co. (2012) Facts: P saved points for 15 years for Camel Cash rewards Program. D sent notice cancelling the program, but no prizes were available during the last six months. Rule: Not a bilateral contract, it is unilateral. Exchange of a promise for a performance. Purpose of program was to induce as many consumers as possible to purchase Camels. D alone decided how many notes to distribute and could not have had a limited inventory. Advertisements constitute offers where they invite the performance of a specific act without further communication and leave nothing for negotiation. P substantially relied. Notes: Corbin: one party greatly benefited from part performance. Implied duty of good faith and fair dealing. Illusory Contract: If agreement is in the form of a contract, but missing mutual obligation (unfettered ability to rescind) it’s just a promise in form; not enforceable. Mutuality of Obligation: both parties have undertaken substantive promises (opposite of illusory). o Not essential in unilateral contract because there’s only one promise. o 2nd Restatement not a fan of mutuality requirement. But a few courts will apply it. “I’ll sell to you if I feel like it”. Benefits the scoundrel. “Illusory contract” theoretically not a big deal under unilateral contract. If there’s a way to look at illusory contract and make it legit, we enforce; lean in favor of enforcement. Exception: If someone retains discretion on how they perform, is this less than a contract? Look at industry subcultures to see if this is normal (Johnson: “usage of the trade”) o There is an implied assumption of fair trade and fair dealing; industry-specific. Illusory Promise o If at the will of both, then not illusory. If at will of promisor, then yes illusory. o Unenforceable. 6 C. Postponed Bargaining: Agreement to Agree Scenario 1: I’ll sell you my house, but we’ll work out the details next week. o Very weak – unenforceable. Walker v. Keith close to this. Scenario 2: I’ll sell you my house for $500, we’ll meet next week to sign the formal documents. o Should we let people trade this way? Messy. But there is freedom of contract. Promissory estoppel can be used for reliance on letters of intent. Two types of incomplete bargains: o “Agreement to agree”. Walker v. Keith o “Formal contract contemplated”. parties have reached agreement in principle, but contemplate the execution of a formal written contract. Both UCC and Restatement recognize parties may be bound in both situations UCC 2-204(3): Even if one or more terms are left open, contract does not fail for indefiniteness if parties intended to make contract. Walker v. Keith (1964) Facts: P leased a small lot from D with option to renew same terms as original lease, but did not set a new amount for rent. P gave proper notice of renewal, but parties unable to reach agreement on amount of rent. Trial court enforced the option and set rent at $125 per month. Rule: Leaving the terms for future ascertainment, without providing a method for their determination, renders the agreement unenforceable for uncertainty. Notes: Judicial paternalism: Courts shouldn’t waste their time divining terms for indefinite contracts. An “agreement to agree” cannot constitute a binding contract. Nothing could be more vital in a lease than the amount of rent. It is pure fiction to say the court, in deciding upon some figure, is enforcing something the parties agreed to. Consider that open price term was part of consideration for original lease. UCC §2-305: “open price term” will not necessarily prevent enforcement of K for sale of goods. If parties negotiated with intent to be bound by future agreement, court can enforce a “reasonable price”. If one party has power to fix the price, they must do so in good faith. Under UCC, price may not be an essential term, but quantity is. 2nd Restatement: endorses UCC §2-305 for non-goods. Quake Construction, Inc. v. American Airlines, Inc. (1990) Facts: American Airlines cancelled agreement with GC for construction of new facilities. SC alleged letter of intent by GC was a binding contract. Issue: Whether a letter of intent is an enforceable contract such that a cause of action may be brought. Rule: To draft a letter of intent that is not binding include no cancellation clause (if the parties did not intend to be bound by the letter, they had no need for a cancellation clause) and no essential terms. When there’s a complicated deal, then we want more formal agreement. This letter of intent is ambiguous. Court must consider: o Whether the type of agreement involved is one usually put in writing. o Whether the agreement contains many or few details. o Whether the agreement involves a large or small amount of money. o Whether the agreement requires a formal writing for the full expression of the covenants. o Whether the negotiations indicated that a formal written document was contemplated at the completion of the negotiations. o Where in the negotiating process that process is abandoned. o Reasons why it is abandoned. o Extent of assurances previously given. o Other party’s reliance on the anticipated completed transaction. 7 Remanded. i. Good Faith Bargaining For letters of intent, either: o 1) parties intended to be completely bound by a letter of intent (courts may have to fill in the blanks); o 2) they didn’t and there is no mutual obligation; or o 3) letter of intent binds parties to negotiate in good faith to attempt to reach agreement on a contract, but reserved the right to terminate negotiations. Policing this is difficult – court expected to identify damages and fashion a remedy. Calculating expectancy measure of damages is hard when you only have good faith. An “agreement to agree” is not a binding contract. Parties can agree to main terms and then leave details to a “second team of bargainers” (lawyers, accountants, etc.). Bargaining in good faith means both sides should not be completely bound if later unable to agree. Middle ground between pure negotiation and complete agreement. II. CONSIDERATION Value given by one party in exchange for performance or a promise to perform. “Benefit/detriment test”: benefit to the promisor, detriment to the promisee. Consideration = detriment (surrender of something I’m otherwise not obligated to surrender like a legal right) o Not about benefit. My promise induced you to incur this detriment. “Bargain theory” of consideration: parties must have bargained for (agreed to) an exchange of promises, so that each induces the other. “Bargained-for exchange” in the commercial context. o It’s hard to find cases dealing with consideration in the commercial context. Judges work hard to scrape the barrel and find consideration: o Court may stretch to find consideration when the promise appears to be seriously intended and fairly obtained, but may more readily apply the doctrine to invalidate a promise that appears to have resulted from unfair dealing. Obligation without consideration may not be a contract, but it can still be enforced with alternative theories (promissory estoppel, restitution, or moral obligation). You assign rights, you delegate duties. 1nd Restatement §75?: Nominal consideration not enough. But Courts almost never enforce this; will consider the smallest thing consideration (peppercorn). 2nd Restatement §71: Courts shouldn’t inquire into adequacy of consideration, but false consideration that does not in fact induce the return promise should not be treated as sufficient) Hard to find cases where courts have said this fails because only nominal consideration. Partly because courts trust valuations by the parties. Hamer v. Sidway (1891) Facts: Uncle promised nephew $5,000 if nephew didn’t use alcohol or tobacco until 21st birthday; after nephew followed through and turned 21, uncle promised $ with interest later; uncle died not having given him the $ Rule: Waiver of legal right by another party is a sufficient consideration for a promise. Analysis: Surrender of a right caused the promise. D claimed no consideration because no benefit to promisor (“benefit/detriment” test). Focus here is on detriment. Pennsy Supply, Inc. v. American Ash Recycling Corp. of PA (2006) 8 Facts: Paving materials obtained without cost from D by paving SC P. After construction of driveways, paving started to crack. P disposed of the material without charging the district for the repairs. Rule: Bargain theory of consideration doesn’t require parties bargain over the terms of the agreement. Notion of bargaining here, is not synonymous with negotiation. Reciprocal inducement is all that’s required. Quid pro quo. Notes: Maybe no consideration, but just a gift with a condition. The law regards the making of a promise as sufficient legal “detriment to bind the promisor to a return promise of his own under the benefit/detriment test for consideration”. Judges push hard to find consideration, you should too. Conditional Gift vs. Consideration “Tramp” Example – rich man says “go get a coat if you walk around the corner”. Walking is a condition to delivery, not consideration for the gift. Rich man could revoke the gift promise before he gets the coat. To resolve issue of gift vs. contract, ask: “was the condition beneficial to the promisor?” Dougherty v. Salt (1919) Facts: Aunt visiting P, eight-year-old nephew, stated she thought P was a “nice boy”. Aunt expressed desire to take care of P by issuing a promissory note. “You have always done for me, and I have signed this note for you.” Note written on a form containing the words “value received.” Rule: No consideration; Voluntary and unenforceable (executory) gift. Consideration must be regarded as such by both parties. No detriment to the child here. Cash for past service doesn’t fit quid pro quo model. Past consideration is no consideration. Legal Formalities 1. Evidentiary function 2. Cautionary function a. Need to deliberate before acting against the promise. 3. Channeling function a. Facilitation of judicial diagnosis/remedy. Donative Promises Involve neither formality nor explicit reciprocity. Potential for revocation or excuses (abuse) abound. Not enforceable without consideration Promise under seal – outdated. Executed gift – paid now; good. Testamentary gift – by will; could be superseded by later will, not payable until all debts satisfied. Gift in trust – becoming more popular. Promissory note – not useful. Dohrmann v. Swaney (2014) Facts: Adult adoption. Both signed a contract; D was 89 at the time and two years away from dementia. No witnesses present and P never told her long-time lawyer. Contract for $ and apartment in exchange for “past and future services” and continuing the P name by including in children’s’ names. Changed both middle names. Rule: Where consideration is grossly inadequate and shocks the conscience of the court and shows unfairness, contract will fail. Notes: Whether a contract contains consideration is a matter of law, not fact. Disproportionate bargaining power (uneducated and old/dementia, vs. educated neurosurgeon. Johnson: Evidence of gross inadequacy or consideration has been considered tantamount to creepy cases. This case is the most aggressive assault on classical notions of consideration. More traditional assault is to focus on other issues (creepy cases). Analytically it’s a question of which arguments you approach first. Plowman v. Indian Refining Co. (1937) Facts: Employees were fired, promised half-pay for “faithful service” until death or until company ended (different stories). After 1 year, half-pay stopped, they sued. 9 Rule: Past or executed consideration is self-contradictory. Act of picking up checks was merely a condition, not consideration; arrangement gratuitous. Letters said nothing about a time limit. Moral consideration is not valid consideration unless the moral duty was previously a legal duty. Appreciation of P’s service not valid consideration to make promise enforceable. Agreement revocable at the pleasure of D. Notes: What was the quid pro quo? Perhaps consideration given by employees was “industrial peace” – morale. Agency Consensual relationship in which one person, the agent, agrees to act on behalf of, and subject to the control of, another person (or corporation), the principal. o A fiduciary relationship/duty Principal may be bound by agent actions if principal has represented to other party to believe the agent does have that authority o “Apparent authority” – who do I have to go to in order to get this transaction approved? Board of trustees? “Actual authority” / “express authority” to perform acts necessary to achieve the principal’s objectives “Implied authority” Ratification: if agent not authorized, but principal approves. Marshall Durbin Food Corp. v. Baker (2005) Facts: D agreement former employee P that upon occurrence of certain triggering events, like incapacity of D, P would be entitled to five years of his current salary. Contract entered into for consideration of $10 and “other valuable consideration”. When D declared incapacitated by the court, P informed D that the triggering event had occurred and he would now be working as a contractor and not an employee to D. D died, board was dissolved, new board repudiated the agreement. Rule: Company’s promise was contingent (unilateral), not illusory. I’ll sell to you if this happens; “So long as”; “if”; “only when”.) Legal detriment present where the promisee gives up something he was privileged to retain prior to the contract (as opposed to detriment-in-fact). Presence of an illusory promise may create a unilateral contract. Employers side of the issue was illusory, employment at will – could have fired Baker at any time. Some jurisdictions say that when one side is illusory, the whole contract is unenforceable. Picking up the paycheck was the equivalent of a condition (Tramp example) – just a gift with a condition. Notes: Plowman: pay dollars for gratitude. Durbin: Pay dollars in exchange for continued employment (though he could still walk away). jurisdiction allows for unilateral contracts, but still like mutuality of obligation for bilateral contracts. 2nd Restatement §77: promise is not consideration if illusory (entirely optional to promisor; “at will”). III. UCC FORMATION: Article II Governs the sale of goods (between consumers and consumers, merchants and merchants, and merchants and consumers) o Goods = “movable property” (car or computer) (commercial or consumer). How movable? Fixtures? Buildings? Direct response to change in mode of trading in the world; people weren’t reading forms when trading goods. Supplemented by local common law. Very different outcomes depending on which law applies: Common law or UCC. Predominant Purpose/Thrust Test: Goods must be the predominant aspect of a trade, when there is a goods + services combo, to fall under UCC. (Fact-intensive inquiry.) A. Mutual Assent Under the UCC UCC §2-204: (contract formation) – formation more flexible than rules of formation under CL; encourages courts to consider business practices to resolve formation disputes. 10 2-204(1) recognizes oral contract formation: “any manner sufficient to show agreement”. 2-204(2): “an agreement sufficient to constitute a contract for sale may be found even though the moment of its making is undetermined.” 2-204(3): “Even though one or more terms are left open, a contract for sale does not fail for indefiniteness if the parties have intended to make a contract.” UCC § 2-201: (Statute of Frauds): Any deal over $500 must be in writing. Jannusch v. Naffziger (2008) Facts: P sold D Festival Foods truck + goodwill (habit of the customer in relation to the brand). Took out the truck, paid taxes, paid employees. Talk of future formal meeting/document. Rule: Predominant purpose test: sale of goods here. Under UCC, conduct indicates agreement. E.C. Styberg Engineering Co. v. Eaton Corp. (2007) Facts: Both parties previously had transactions creating and shipping brakes. Engaged in back and forth talks over amounts. Rule: Essential terms not agreed upon. No repeated and ongoing conduct (Course of Dealing). Disagreement over quantity – tough to see how they came to an agreement. Doesn’t work under UCC §2-204; No agreement on quantity, no contract. Johnson: sometimes price can be inferred; but quantity is essential. B. The “Battle of the Forms”: Qualified Acceptance Where at least one party is not a merchant, new terms fall away Where both parties are merchants, new terms fall in, unless 2-207 (2)(a), (b), or (c) § 2-207: Additional Terms in Acceptance or Confirmation (1) A definite and seasonable expression of acceptance or (a written confirmation) which is sent within a reasonable time operates as an acceptance even though it states terms additional to or different from those offered (or agreed upon), unless acceptance is expressly made conditional on assent to the additional or different terms. [Dismisses mirror image rule.} (2) The additional terms are to be construed as proposals for addition to the contract. Between merchants such terms become part of the contract unless: (a) the offer expressly limits acceptance to the terms of the offer; (b) they materially alter it; or (c) notification of objection to them has already been given or is given within a reasonable time after notice of them is received. (3) Conduct by both parties which recognizes the existence of a contract is sufficient to establish a contract for sale although the writings of the parties do not otherwise establish a contract. In such case the terms of the particular contract consist of those terms on which the writings of the parties agree, together with any supplementary terms incorporated under any other provisions of this Act. Varying Acceptance Non-matching communications can form a contract under 2-207. Princess Cruises Inc. v. General Electric Co. (1998) Facts: Princess contracted with GE for ship repairs. Repairs resulted in damage and cancelled cruises. Procedure: Trial court mistakenly analyzed the contract under UCC, because they claim it’s a maritime contract. But appellate court says admiralty would defer to common law. Rule: When K for both goods and services, UCC applies if the predominant thrust/purpose is sale of goods. Consider Coakley Factors (below) to make the determination. At CL, acceptance that varies the offer is a rejection and counteroffer. Terms of last offer control. Last Shot Rule: person who fires last shot wins. Only 11 concerned with acceptance by performance, rather than explicit acceptance. Worry about giving too much impact to last document. Princess dealt specifically with “Service department” – name (label) of department is consistent with the purpose at hand. Johnson: Should we move in the direction of the UCC (lenient on contract terms) for non-goods transactions? Coakley Factors For determining goods or services (predominance test): 1. Language of contract. 2. Nature of the supplier’s business. 3. Intrinsic worth of materials. Knockout Rule Cancel out any offer and acceptance terms that differ, but keep the rest of the contract. Brown Machine, Inc. v. Hercules, Inc. (1989) Facts: D responds to P purchase order form with acknowledgment containing indemnity (liability) provision. Rule: To make a more solid contract, demand/condition acceptance upon express assent of other party. No magic language here, so acknowledgement is an acceptance, NOT a counteroffer. Under 2-207(2), additional term (indemnity clause) was a material alteration, so knocked out. Assent. Notes: Whole purpose is to avoid the sins of the “last shot” rule. One of the reasons we end up with imperfect versions of the magic language is opposing party gets wind of the stipulation and clearly see it as unfavorable. Material Alteration: “Surprise and Hardship” Test: Answers what constitutes a material alteration? Posner: you can’t just claim hardship, because then anyone with buyer’s remorse would take advantage. What we’re really looking for is surprise (in context). Is it common in the trade for this sort of term to appear? (usage of the trade). Not reading the form hurts you when making the surprise argument. Look at the mosaic: The more factors you have showing surprise, the better off you are. Paul Gottlieb & Co. v. Alps South Corp. (2007) Facts: P created prosthetics, contracted with D for fabric. P upset about worse fabric being used and wants to transfer costs to D. D didn’t give notice about costs. Limitation of damages clause in contract. Issue: Is this clause a material alteration? Rule: Both merchants, terms fall in under UCC. Must prove contract was materially altered. Surprise and hardship test. Court says no surprise here. Can’t get away with not reading terms. (Hard rule to square with modern cases.) Johnson: Court standard consumes the rule: any term included in the form can’t be a surprise and is therefore not a material alteration. Terms are part of bigger industry story: you should not be surprised to have these terms in a contract because everybody knows about these terms in this industry. Once you make these terms part of the mosaic, then inclusion of term in contract doesn’t equal material alteration. Johnson: Offeror and offeree identities are contestable, but outcome determinative. 2-207 triggered when offeree accepts. If buyer doesn’t inform seller of potential for consequential damages (notice), surprise exists. Notes: Many books recommend the knockout rule. NOTE 1: “duty to read”: part of fact-intensive kind of assessment. Tell the cultural story. NOTE 2: Additional vs. Different Terms. Courts tend to say that inclusion of different terms drops out (majority). C. CISG (Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods) Applies when parties are from different countries. o Subsidiaries in the same country don’t count. UK not a signatory. Excludes consumer transactions. Parties can waive CISG rules in a contract, and choose some other source of law. Offer must include sufficiently definite list of goods, quantity, price, and willingness to be bound upon acceptance. 12 III. ELECTRONIC & LAYERED CONTRACTING Shrinkwrap Terms: upon opening plastic wrap, contract states certain number of days by which purchaser can return. No return is assent to the contract. o Called “rolling contracts” or “layered contracts”. Clickwrap Terms: before completing purchase, purchaser must scroll through the seller’s terms of sale and click “I agree.” o Sometimes initials required. Browsewrap Terms: by using a site, user agrees to terms of use that may not be in your face. No agreement. DeFontes v. Dell (2009) Facts: P wants to get out of Dell contract. Dell refund policy has improper tax. Rule: Test: whether a reasonable person would have known that return of the product would serve as rejection of terms. Terms of rejection unclear. Consumer right to reject terms not reasonably apparent, thus additional terms (tax) cannot be part of contract under UCC. No adequate notice for procedure to reject terms. Agreement illusory because it provided for Dell to change at a whim. Notes: Is software considered a “good” under the UCC? Unknown. Hines v. Overstock.com, Inc. (2009) Facts: P buys vacuum on Overstock.com and decides to return. Charged $30 restocking fee and filed class action. Overstock mentions arbitration provision to avoid class action. Overstock said accessing site is tacit agreement (even though terms in hyperlink at bottom of page). Rule: Notice is essential to assent and browsewrap is not enough; no affirmative assent needed. Notes: Where terms hidden, contract unenforceable. Website design must be calculated to force assent. Johnson: Compare Hines with Feldman: Both similar in theme of notice, but they offer different arrangements/notice of their terms (click agree vs. find link at bottom of page). Easterbrook on Layered Contracting What if new terms include you must pay $10,000? Unconscionable. What if only a $50 fee? Unknown. When purchaser places order for either software or hardware, purchaser has NOT made an offer. Vendor is “master of the offer.” If purchaser doesn’t return product, bound by vendor’s terms Policy: at the time of order, software company could read out terms of contract, but buyers wouldn’t like that: inefficient, ineffective, costly, so inclusion of terms in package is acceptable. Critique: Easterbrook says that initial action by buyer was a non-event. But then what is everything else that comes before that? There’s the advertisement, the buyer handing over $, etc. Concluding that the seller is making the offer allows court to solve problem more easily, but opens up a new world of abuse. IV. PROMISSORY ESTOPPEL Promise + Reliance + Justice (Don’t confuse consideration with reliance.) Antithesis of classical bargain theory. Contracts & PE are “matter and anti-matter” Reliance is simply detriment (no matter what it is). Want to protect people from “detrimental reliance”. PE is rarely successful except in situations of imbalance of bargaining power o There are siloes of cases where PE usefulness is higher: family & charity. Enforcing a promise without a corresponding reciprocal promise is confusing under contract law (no real trade/exchange). No quid pro quo. 13 Comes out of theme of equitable estoppel: if you make a statement or misstatement of fact, and someone acts in reliance on it, then you are estopped from denying that you said it. Promisor is obligated, not promisee. 2nd Restatement § 90. Promise Reasonably Inducing Definite and Substantial Action A promise which the promisor should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance of a definite and substantial character on the part of the promisee and which does induce such action or forbearance is binding if injustice can be avoided only by enforcement of the promise. When deciding whether a promise without consideration should be binding, consider these factors: o A promise was made with reasonable expectation that promisee would rely on it. o Promisor did in fact induce promisee’s action or forbearance; reliance must be justified. o Enforcement of the promise is necessary to avoid injustice. o Remedy may be limited as justice requires. Johnson: o 1st Restatement: reliance had to be of definite and substantial character. o 2nd Restatement: only requires reasonable expectation of reliance. Was it reasonable for P to rely at all? Was the degree and manner of reliance reasonable? o Difference between Restatements: Addition of charitable subscriptions even without detrimental reliance. Allows 3rd parties to bring case. Eliminates requirement of definite and substantial character. Remedies are limited as justice requires. A. Promises within the Family Highest rate of success for PE arguments. Harvey v. Dow (2008) Facts: Daughter built house on family homestead. Led to believe she would inherit the land. Father agreed to let her build the house there, offered to finance, helped build the house. Relationship deteriorates. Rule: She can stay; reasonable reliance on parents’ promises. Families create additional considerations; a Dad is different than Overstock.com. Familial subculture; not really commercial. Notes: Quid pro quo vs. condition (“come home and care for me”). Looks like conditional arrangement, but in the family context it can be better argued as quid pro quo. Reliance may be higher standard than consideration, which only requires a “peppercorn.” B. Charitable Subscriptions Oral or written promise to do certain acts or to give property to a charity or for a charitable purpose. King v. Trustees of BU (1995) Facts: Martin Luther King, Jr. estate ants papers back. Rule: Promise enforced as consideration or as reliance. Court careful about applying principles of enforcement. Was there reliance? We don’t find it in fact of bailment, but extra work of indexing, etc. Notes: Quid pro quo that institution will name a wing after you. 2nd Rest.: charitable subscriptions binding without reliance. Response: some courts have embraced this theme. C. Promises in the Commercial Context Little clarity or predictability here. 14 Katz v. Danny Dare, Inc. (1980) Facts: Employer negotiated with employee to resign and accept pension. After a time, stopped paying pension. Rule: The order has to be promise first, then reliance. Not the other way around. At-will employee had no right to future employment, so he didn’t give that up as consideration. But this isn’t a consideration question, but reliance. Reliance is simply detriment, not a quid pro quo of giving up a right (consideration). Missed opportunity cost due to reliance. Notes: Similar to Plowman – pay based on gratitude for something already done. Past consideration is no consideration. Reliance can be a replacement for consideration, but there is still a timing problem here. Feinberg Different from Katz because offered option to retire with pension at any time she wants. A promise induced her later decision to retire. She had her hands on a paycheck every week. Only reason she gave up the job late was because she had the promise of a pension. Harder case is simultaneous exchange. Missed opportunity cost of 2.5 years before quitting. Pitts Retired first, then got promise of pension; no reliance to his detriment. Timing problem; past consideration is no consideration. But we don’t care about consideration. All we care about is a promise inducing reliance. Not willing to embrace promissory estoppel here because action comes before the promise. Aceves v. U.S. Bank, N.A. Facts: P tries to file Ch. 13 bankruptcy but gave up the opportunity in reliance on the bank’s promise. They didn’t allow refiling. Rules: In CA, reasonableness matters. How does court measure reasonable reliance? P’s objective situation; injustice. Reasonable reliance on bank’s assurances here. Promisor liable for not seriously engaging in negotiation. Notes: Promissory fraud: did not intend to comply with promise at the time you made it. Wrongful – a tort. Misrepresented a material fact. Can result in punitive damages. Hard to prove – need a document/smoking gun. Johnson: Inaction is sufficient reliance. V. LIABILITY ABSENT ACCEPTANCE A. Option Contracts Promise to keep an offer open, supported by consideration. Berryman v. Kmoch (1977) Facts: D had option contract with P for piece of land for $10 consideration that was never paid. D spent time and $ looking for investors, then P asked to be released from contract and sold to another. Rule: Reliance not reasonably foreseeable by P. If you have reliable notice of a revocation before you accept, then properly revoked. No real consideration here because $10 not paid. Recruiting other future buyers is not reliance. Johnson: Court is wrong here. Should be considered an option promise, not a contract. If a bilateral contract, nonpayment does not mean no contract, just means breach of a contract. Under unilateral contract, promise of option is contingent on payment of $10. If never paid, then promise can be revoked. Implicit that an option contract is unilateral. Be careful about revocation; don’t want client in a position where two acceptances come in. Offers can expire by rejection, counter-offer, death, or incapacity of offeror. Option stays in place if you pay the consideration before death. B. Reliance on Unaccepted Offers Baird v. Gimbel (1933) Facts: GC solicits bid (offer) for a public building from SCs. SC sends wrong bid on accident. GC selects SC at cheap price. Sends offer based on SC price. SC withdraws offer. 15 Rule: No contract made. PE does not apply. Promise unenforceable. SC never made aware GC accepted his bid, so no promise. Revocation effective when done before acceptance. Offers revocable until exchanged for consideration (counterpromise or some act). Analysis: Promissory estoppel has no application to quid pro quo. Why? Judge Hand says promissory estoppel deals with reliance on promises; an offer isn’t meant to become a promise until consideration is received. In commercial transactions it does not in the end promote justice to aid those who do not protect themselves. Notes: Do I want the opportunity to bid shop? Or bid chop? Today public contracting has lots of protections for subcontractors. Counterpoint to majority rule in Drennan. Bid Shopping/Chopping SC has ability to revoke if GC is: o Bid shopping: GC tries to find another subcontractor who will do the work more cheaply while continuing to claim that the original bidder is bound. o Bid chopping: GC attempts to renegotiate with the bidder to reduce price. Drennan v. Star Paving Co. (1958) Facts: GC relies on low SC bid (offer) and submits SC identity for contract. SC notifies GC bid was too low from error. GC’s bid is accepted, SC refuses to perform. Holding: GC justifiably and substantially relied on SC’s offer (the bid). GC looks for someone else who can do it close to their bid (mitigation) and sues for damages (difference between new and original bid) Rule: Majority rule for GC-SC contracting. Court held for GC using PE: reasonable reliance held offeror in lieu of consideration (Restatement §90); and (§ 45) no revocation after part performance of or reliance on unilateral contract. Reasonable (reinforced by commercial subculture) that GC would rely on SC bid. Applying PE, the court says “you gotta say it” if retain right to revoke; make an affirmative claim, put revocation mechanism in the agreement (similar to 2-207 “magic language”). Johnson: This merges freedom of contract with PE. We’re uncomfortable trying to merge these two things. If “Unilateral mistake”, harm falls on party that made mistake, unless the party who tries to enforce knew, or should have known, about the mistake. If GC should have realized from low bid that it was probably due to error, GC’s reliance wouldn’t have been justifiable and there would have been no recovery. Notes: Is the court saying a SC can never withdraw a bid? PE only binds the promissor. Looks like unilateral contract: offer made, consideration given, offeror bound. Drennan is in conflict with Baird, and wins. Pop’s Cones, Inc. v. Resorts International Hotel, Inc. (1998) Facts: Negotiation for P to rent storefront from D, who advised P not to renew lease because deal was “95% done,” then withdrew. Rule: Why would court enforce this amorphous promise? Damages sought are only reliance damages, not expectation. Promises are different than offers. Test is whether you can say exactly what offeree/promisee has undertaken to do. If can’t answer, then likely PE. If you can, then contract. Court allows PE claim to move forward because reliance was reasonable and detrimental. We’re looking for justification of court accepting a mosaic of statements that constitute a promise. Johnson: We are willing to count an amorphous promise as long as the remedy matches up to the character of the promise: clear and definite. Not clear here (no price of rent), but court still upheld it because seeking reliance damages (not expectation). Strong imbalance of bargaining power here, even though the ice cream store owner should not have relied on someone with the Resort’s interests. Notes: No more “clear and definite promise” needed. Sophisticated people have higher bar to pass for reliance. Sometimes assurances lead to duty to bargain in good faith. On Shark Tank, the judges would say decision to move out on hope that you will have better premises is a decision about business risk. Why should the law protect someone so dumb? Greater the business experience, the less sympathetic. Here there is a huge disparity in bargaining power. Outlier case of PE; Why would this “precedent” destroy the market? Hoffman v. Red Owl Assurances made during negotiations that a contract will be forthcoming amount to a promise sufficient to invoke 16 PE when promisee has relied to his detriment by giving up another business location and incurring out-of-pocket expenses in preparation for the new location. C. Statutory Limits on Revocation Common law: an offer is revocable unless and until it is accepted by the offeree, even if the offer itself expressly states that it cannot and will not be revoked. “Natural law” (CISG): offer can’t be revoked if expressly stated and if offeree reasonably relied on offer as being irrevocable. UCC is more demanding than PE in making promises irrevocable (Drennan). UCC demands writing and an explicit assurance. PE better where imbalance of power (like Drennan). UCC §2-205: Firm Offers An offer by a merchant to buy or sell goods in a signed writing which by its terms gives assurance that it will be held open is not revocable, for lack of consideration, during the time stated or if no time is stated for a reasonable time, but in no event may such period of irrevocability exceed three months; but any such term of assurance on a form supplied by the offeree must be separately signed by the offeror. Restatement 2nd §43 Buyer’s power of acceptance terminated after learning of sale to someone else. o “You snooze, you lose” rule: Normile VI. RESTITUTION What happens when something falls into your lap that you don’t deserve? Unjust enrichment. When contract claims fail, look at unjust enrichment. Implied-in-fact contract: surrounding facts indicate a trade/contract (ordering food at McDonald’s). Implied-in-law contract: restitution; quasi-contract. Saying there’s a contract when there isn’t. o Elements of a cause of action for a quasi-contract: P has conferred benefit on D. D has knowledge of benefit. D has accepted or retained the benefit conferred. Circumstances are such that it would be inequitable for D to retain the benefit without paying fair value for it (unjust enrichment). A. Restitution Absent a Promise Restatement 3rd of Restitution §107: A person who has supplied things or services to another, although acting without the other’s knowledge of consent, is entitled to restitution if: He acted officiously and with intent to charge. Services were necessary to prevent the other from harm. The person supplying them had no reason to know that the other would not consent to receiving them. It was impossible for the other to give consent or, because of extreme youth or mental impairment, the other’s consent would have been immaterial, Comment to Restatement: if person is insane, even if refuses to accept services, other party entitled to recover. No restitution where a contract gives express terms of bargain. Officious Intermeddler: scenario where someone finds your property and protects it; deserve compensation. What happens if a random pedestrian stops to help someone injured on the street? o Maybe just a Good Samaritan – no payments necessary. o Maybe under Pelo you should get paid. Credit Bureau Enterprises, Inc. v. Pelo (2000) Facts: Guy incarcerated and unwillingly brought into care of hospital. Refuses to pay. Rule: Benefitted party may be required to make restitution; contract implied-in-law (3rd RST of Restitution §116). 17 Notes: We want people to give care to people who cannot assent. Hospital bill is not contractual; they should get paid the reasonable value for their services in restitution. Commerce Partnership v. Equity Contracting (1997) Facts: D contracted GC who contracted SC. SC (P) claims it was not paid. GC bankrupt, but already paid by D. Rule: Did P had exhausted his ability to get remedy from original breacher? If D paid someone the value, then no restitution to another because no unjust enrichment. SC can only recover against property owner if 1) exhausts all remedies against GC, and 2) owner hasn’t already paid GC. Johnson: Implied-in-fact contract case stronger if SC was connected with owner in some way. Was D unjustly enriched? No. D paid GC (even though GC didn’t pay SC). Notes: Not all courts accept this standard. Tenant-contractor-landlord agreement: tenant hires contractor for aesthetic improvement of home without landlord knowing about it. Majority of courts: landlord escapes liability because of lack of knowledge, no opportunity to stop work from being done. Watts v. Watts (1987) Facts: Couple lived together for 12 years, had two kids, built a business together, and broke up. Woman sues for her share of couple’s property, even though not married. Rests her claim on equitable division of property. Rule: Should we enforce illegal contracts? Both parties have “unclean hands”. Looked at value of services she offered (would have been different if married). Arguments: “Marriage by estoppel” argument. Notes: Marvin v. Marvin: court began to contemplate that married cohabitants could bring these sorts of claims. Intra-family claims: presumption of gratuity for families; should they be deemed family as cohabitants Johnson: Should parent be able to bring restitution claim against kid for value of education. How much more attenuated before the presumption of gratuity fades? Emancipated child? Older child returning to take care of parents? Illegality/Unclean Hands: How should we treat two drug dealers who have a contractual argument over an oz of weed? If we are hands-off to illegal contracts like this? Person who seeks equity, must do equity. You must come to equity court with “clean hands”. B. Promissory Restitution Middle ground between classical contracts and pure restitution. When recipient of services makes an express promise to pay for them, but only after the benefits are received: classical contract theory would hold promise not binding because it’s past consideration. Restatement §86: Material Benefit Rule: if a person receives a material benefit from another, other than gratuitously, a subsequent promise to compensate the person for rendering such benefit is enforceable. (Not all courts follow.) Mills v. Wyman Facts: P helps D son who later died. D said will pay P back. P brought suit to enforce promise. Rule: Promise not binding because past consideration is no consideration and moral consideration is no consideration. In some cases, court will enforce promissory restitution if promise remade (usually for economic reasons), when: o Contract enforcement barred by SOL and promissor agrees to pay the money anyway. o Infancy/Incapacity (decide to go back later and pay) “Infancy doctrine”. o Barred by bankruptcy, if want to pay anyway, because original quid pro quo. Johnson: Why as a policy reason do we want to enforce these promises? o Originally quid pro quo; not a matter of logic (natural justice). o We prefer creditors get paid so they continue to give credit. o Benefit to consumer to later access credit by restituting/redemption. o Maybe they want to do business again with these people. Can re-establish yourself as a “good risk”, as a viable trading partner. Webb v. McGowin (1936) Facts: Factory worker saved D’s life, injuring himself instead. D promised to pay P $15 every two weeks for life. 18 Rule: When promisor receives material benefit from promisee, promisor morally bound to repay. If promisor vows to make payment on that obligation, valid and enforceable. Moral obligation + material benefit + subsequent promise can be an exception to “past consideration is no consideration”. Notes: Outlier case; logic is hard to square. RST §86. VII. STATUTE OF FRAUDS Courts must often choose between injustice of enforcing a possibly fraudulent claim and injustice of refusing to enforce a possibly honest one. Courts err in favor of disregarding the Statute of Frauds because minimal consequences, no definitive outcome, just allows the chance to prove at oral argument. Linking documents: o Restatement Comment: Even if no internal reference or physical connection, documents may be read together if they clearly relate and the party to be charged has acquiesced in the contents of the unsigned writing. Courts seem readier to combine writings if P’s story is persuasive. Three Main Inquiries 1. Is it “within” the statute? a. Restatement (Second) §110 requirements: i. Executor to answer for a duty of his decedent. ii. To answer for the duty of another (suretyship). iii. Upon consideration of marriage. iv. For sale of land: 1. Can apply to transfer of interests in land other than sale, including easements, mortgages, and leases. v. Not to be performed within one year from its formation: 1. Contract is not subject to statute if it is possible to be performed within a year, even if the prospect is unlikely. 2. Possibility of termination within one year doesn’t remove from statute. 3. Lifetime contracts qualify under one-year clause. 2. Is the statute satisfied? a. Writing/signature requirement (no signature requirement for UCC). i. Restatement and UCC take liberal view of “signed writing” (UCC allows a printed letterhead). ii. Situation in which a writing can be enforced against party who didn’t sign it: 1. Both parties are merchants. 2. Within a reasonable time of oral contract, one party sends written confirmation to other party (signed by sender). 3. Recipient has reason to know of contents. 4. No objection to written confirmation within 10 days. iii. Doesn’t guarantee performance- just allows sender to prove at oral agreement 3. Is there an exception? a. Part performance (only for equitable remedy of specific performance) i. Traditional rule applies to land transfers: 19 1. Valuable improvements; or 2. Taking possession and paying part of purchase price. ii. Modern rule: 1. Part performance that provides reliable evidence that a contract was made. 2. When refusal of enforcement of K would be too rigid- courts often require some degree of prejudice to have been suffered in reliance on the agreement. 3. Courts don’t always enforce this exception. iii. For contracts for sale of goods (UCC): 1. Specially manufactured goods 2. Seller has received and accepted payment a. Partial payment will validate entire K if goods cannot be apportioned 3. Buyer has received and accepted goods One Year Provision Can’t be possible within one year. Even contract to build Taj Mahal could be done in one year. Theoretically can this be done in one year? I have the power to breach the contract immediately, but not the right to terminate. We don’t include a contract’s termination (within one year) in the calculation. Crabtree v. Elizabeth Arden Sales Corp. (1953) Facts: Company president refused to honor a bonus promised to P in two different payroll memos. Said no contract existed, but if it did, barred by SoF. Issue: Can we stack signed and unsigned documents? Rule: Multiple documents sufficient if refer to same writing and signed by responsible party; fit under statute of frauds. Because the contract cannot be performed in under a year, it falls under the statute of fraudsIt may be multiple documents if they are linked together expressly or internally by evidence of subject matter and occasion. Notes: The memo written on the telephone order, the payroll change form initialed by D’s general manager, and the paper signed by D’s comptroller all refer to the same transaction on their face. Justified in finding that the 3 documents comprised a sufficient memo. Contract not subject to the statute of frauds if it is possible to be performed within a year, even if the likelihood is remote. Contracts of no duration or indefinite duration are thus not within the statute of frauds Johnson: We need a signature. Under Second Restatement, you want to push hard on question of whether there is a signature. But people manifest assent in a variety of ways (on her letterhead). Judges want to be friendly to harsh impact of SOF. Robust/rigid rule: documents must explicitly refer to each other. Looser/Crabtree rule: only have to be talking (can be oral) about the same thing. Policy: Better to run the risk of fraud than to deny enforcement to all agreements, merely because the signed document made no specific mention of the unsigned writing. Crabtree Rule for multiple disparate writings to constitute same contract (loose rule): 1. Signed writing must itself establish a contractual relationship between the parties. 2. The unsigned writing must refer to the same transaction as the signed writing. Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 133 A memorandum sufficient to satisfy the statute of frauds need not have been made as a memorandum of a contract. Johnson: Judges want to be friendly to harsh impact of SOF. A. Part Performance Beaver v. Brumlow (2010) Facts: Parties work together. Employee got land promise from boss and moved onto land. After hired by competitor, boss rescinded promise, after already living there. Never formalized contract for sale. Rule: Agreement within SoF because sale of property. But partial performance exception if “unequivocally referable: outside viewing the situation would “reasonably and naturally” conclude that a contract exists. 20 Payment of fair market value by appraiser will be specific performance. Court willing to do this based on equity; remedy being pled is outcome determinative (asked for specific performance, not damages, which put them into court of equity). Analysis: Two part performance variables: 1) Did you take possession of property? 2) Did you make valuable (“permanent”, “substantial”) improvements? These signals, are the test for adequate part performance for sale of land to justify exception to SOF. Notes: What if the P’s did not take possession and no improvements, but they did cash in the 401k and down payment on mobile home? Equitable argument still exists – clear elements of reliance. Land is unique. Specific performance based on fair market value. Johnson: *Handshake agreement to sell house fails for indefiniteness. Missing term is price. Looks similar here. How is it that we can reconcile Beaver with Johnson’s example? EQUITY. We are “in equity” here, because specific performance is an equitable remedy. Equity is looser than law. § 129. Action In Reliance; Specific Performance (Part performance doctrine) (1) A contract for the transfer of an interest in land may be specifically enforced notwithstanding failure to comply with the Statute of Frauds if it is established that the party seeking enforcement, in reasonable reliance on the contract and on the continuing assent of the party against whom enforcement is sought, has so changed his position that injustice can be avoided only by specific enforcement. B. Estoppel Equitable estoppel: If one party claims there is a writing or one will be made. Promissory estoppel and the SoF (Restatement § 139). Elements: o A promise reasonably expected to induce reliance. o Inducement of justifiable reliance on promise. o Need to enforce the promise to prevent injustice. o No other legal remedy (like restitution) available. o Reliance of “definite and substantial character”. § 139. Enforcement by Virtue of Action in Reliance (PE) (1) A promise which the promisor should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance on the part of the promisee or a third person and which does induce the action or forbearance is enforceable notwithstanding the Statute of Frauds if injustice can be avoided only by enforcement of the promise. The remedy granted for breach is to be limited as justice requires. (2) In determining whether injustice can be avoided only by enforcement of the promise, the following circumstances are significant: (a) the availability and adequacy of other remedies, particularly cancellation and restitution; (b) the definite and substantial character of the action or forbearance in relation to the remedy sought; (c) The extent to which the action of forbearance corroborates evidence of the making and terms of the promise, or the making and terms are otherwise established by clear and convincing evidence; Page 21 (d) the reasonableness of the action or forbearance; (e) the extent to which the action of forbearance was foreseeable by the promisor. Alaska Democratic Party v. Rice (1997) Facts: P working with Dem. Party and offered employment on Gore campaign. Accepted offer, resigned, and moved to Alaska; obvious reliance on oral contract. Within SoF because explicit contract for more than one year. Issue: What exceptions to SoF exist? Rule/Analysis: Awarded damages. PE can be an exception to SOF. Court here adopts § 139 of Second Restatement (majority): PE may be invoked to enforce an informal contract, notwithstanding SOF, if only way to remedy injustice. Notes: Why is restitution an important consideration here when thinking about alternative remedies? Restitution is an “equitable” remedy (not legal, like unjust enrichment.) If no remedy at law (SoF prevents enforcement at law), we move to restitution (in equity). Does justice demand relief in equity? §178 of the 2nd RST: reflects a middle ground between courts that do not create a reliance exception to the statute of fraud and the courts that adopt §139 that will broadly apply oral agreements simply because there was reliance. Unclear which is majority/minority, but more towards §139. 21 C. Statute of Frauds under UCC Value of >$500 must be in writing. Reduced writing requirement to: o Signed or authenticated. o Indicated contract made (oral evidence). o Quantity listed. UCC § 2-201. Formal Requirements; Statute of Frauds. (1) Except as otherwise provided in this section a contract for the sale of goods for the price of $500 or more is not enforceable by way of action or defense unless there is some writing sufficient to indicate that a contract for sale has been made between the parties and signed by the party against whom enforcement is sought or by his authorized agent or broker. A writing is not insufficient because it omits or incorrectly states a term agreed upon but the contract is not enforceable under this paragraph beyond the quantity of goods shown in such writing. (2) Between merchants if within a reasonable time a writing in confirmation of the contract and sufficient against the sender is received and the party receiving it has reason to know its contents, it satisfies the requirements of subsection (1) against such party unless written notice of objection to its contents is given within 10 days after it is received. (3) A contract which does not satisfy the requirements of subsection (1) but which is valid in other respects is enforceable [exceptions]: (a) if the goods are to be specially manufactured for the buyer and are not suitable for sale to others in the ordinary course of the seller's business and the seller, before notice of repudiation is received and under circumstances which reasonably indicate that the goods are for the buyer, has made either a substantial beginning of their manufacture or commitments for their procurement; or (b) if the party against whom enforcement is sought admits in his pleading, testimony or otherwise in court that a contract for sale was made, but the contract is not enforceable under this provision beyond the quantity of goods admitted; or (c) with respect to goods for which payment has been made and accepted or which have been received and accepted. Merchant Definition (§ 2-104 (1)) "Merchant" means a person who deals in goods of the kind or otherwise by his occupation holds himself out as having knowledge or skill peculiar to the practices or goods involved in the transaction or to whom such knowledge or skill may be attributed by his employment of an agent or broker or other intermediary who by his occupation holds himself out as having such knowledge or skill. Who is a merchant is contestable. Jeff Bezos at Amazon? o Farmers engaged in practice of growing grain are not deemed merchants in different transactions with commercial grain elevator operators. Disparity in bargaining power; broker buys and sells daily; farmer does so infrequently. 22 Can anyone who sells any good of any kind be a merchant? Or only when specialized in one product? What constitutes a signature/writing? Does secretary’s stamp count as acceptance between merchants? § 2-201(c) – “reason to know of its contents” (notice) o Signature/stamp is a diversion; who is the party and do they know of contents? o Core of 2201 simply requires notice, not a signature. Buffaloe v. Hart (1994) Facts: Tobacco barns being sold; movable goods. Handshake agreement to buy. Check is unsigned, and fails because D tears it up before cashing. Biggest failing here may be the signature. Rule: Insufficient to meet UCC writing requirement: Name, signature. Describe property (5 tobacco barns). Amount, representing at least partial payment. What is agreed price? Still enforeceable. Falls within exception: partial performance exception to SoF applies. Seller did not return check for 4 days, indicating check accepted as partial payment. Notes: Saying SoF is satisfied doesn’t mean all the terms are reflected. We may have to embellish those terms from the course of trade. INTERPRETATION VIII. PRINCIPLES OF INTERPRETATION Whose meaning controls? What was that party’s meaning? Interpretation vs. Construction (judicial role of determining the legal effect of language). What drives judicial decision-making? Subjectivist Approach: required meeting of the minds or no contract. (Holmes’) External approach: words understood by normal usage. o Criticism: language could be given a meaning that neither party intended. (Williston’s) Objective theory: reasonable person familiar with the circumstances (even a third party). (Corbin’s) Modified Objective approach: courts should ask: 1) whose meaning controls the interpretation of the contract? and 2) what is that party’s meaning? o Avoids problem of interpreting based on what a reasonable person who is not even a party to the contract would have assumed it meant. 2nd Restatement §201: if both parties attach the same meaning, done (even if contrary to reasonable person). If parties attach different meanings, agreement interpreted in accordance with one party if other party knew or had reason to know of the other party’s meaning. If parties had different meanings, and they didn’t know the other held a different meaning, then no mutual assent and no contract. §201(2)(b): Contractual ambiguity should generally be resolved against the party who drafted the language in question. (Contra proferentem). Joyner v. Adams (1987) Facts: P contracted to develop property with lots. Time to “develop” set, but ambiguity as to whether construction should be completed or only begun by end date. Issue: How do you deal with a disagreement over meaning? Do we know who drafted the document? Rule: Court needs to find D knew or should have known of P’s meaning, or no case. Privilege innocent party’s meaning. Ambiguity construed against person who drafted contract. We don’t know who drafted, so remanded. Notes: Adhesion contracts are like contracts with immense disparities in bargaining power; usually decided against drafter. Johnson: Usage of trade concerns; what are the borders of usage of trade definition – national? 23 Types of Ambiguity Patent/intrinsic: words are unclear, all courts allow evidence to determine meaning. Latent/extrinsic: ambiguity not apparent from the words alone. How do we figure out the terms of an ambiguous contract? “Four corners” / “plain meaning” approach: o The plain meaning of words dominates interpretation o Most words have more than one meaning, but most courts at least require that an agreement be ambiguous before extrinsic evidence is admitted. Modern approach: o Accepts that most words have more than one plain meaning, admits extrinsic evidence to determine meaning. Types of extrinsic evidence admitted to determine intent (Johnson’s pyramid). Express words used by parties Course of performance: discussions and conduct of parties during negotiations. Course of dealings: Any relationship parties may have had in similar or analogous transactions. Trade usage or custom: meaning of words according to a particular industry. General impression. UCC §1-103: to interpret a goods contract, use usage of trade, course of performance, and course of dealing. Frigaliment Importing Co. v. B.N.S. International Sales Corp. v. Adams (1987) Facts: D did not have knowledge of what “chicken” means in the industry (ambiguous). D is new to the trade. Testimony coming from other industry experts testifying as to use of words “chickens.” Rule: With respect to trade usage, when one party is not a member of the industry, the other must prove that the new party had 1) actual knowledge, or 2) that the usage is so pervasive that the party’s acceptance may be presumed. Notes: At what point do we decide you’re a player in the industry? Do you have experienced personnel? Relational contract theory suggests that repeat players may assume things. Does selling this low ever happen? Johnson: Can the drafters adopt a different definition than typically used in federal regulations? There will be overarching regulatory structures that take precedence over common law. Do we have the opportunity in a private arrangement to shift definition that control many transactions in this context/industry? C&J Fertilizer v. Allied Mutual Insurance (1975) Facts: Insurance policy wouldn’t be enforced because needed marks on exterior of premises to prove burglary. Rule: Explicit language not enforced when not within objectively reasonable expectations of other party to the contract. Term unreasonable if still evidence of third-party burglary elsewhere. Notes: We don’t like insurance companies so we have special rules for them (even Williston knows this). Nobody reads an insurance contract. Even if they did, they wouldn’t understand it. Lots of times it’s read after transaction performed. Vast disparity in bargaining power; no ability to negotiate (adhesion). Court suggests it will remake contract for you (contradicts every principle of formation. Here, we step away from duty to read. Johnson: What is peculiar about insurance companies and how far is that from layered contracts? How much more reasonable could layered contract be? 2nd Restatement §237: Explicit language not enforced when not within objectively reasonable expectations of other party to the contract. Reasonable Expectations Doctrine IX. PAROL EVIDENCE RULE Parol Evidence: extrinsic evidence (oral and written) of prior agreements or negotiations. Rule: When the parties to a contract have mutually agreed to incorporate a final version of their entire agreement in a writing, neither party will be permitted to contradict or supplement that written agreement with “extrinsic” evidence (written or oral) of prior agreements or negotiations between them. o When the writing is intended to be final only with respect to a part of their agreement, the writing may not be contradicted, but it may be supplemented by such extrinsic evidence. 24 o Rule operates only to exclude evidence. Classical (Williston) (“four corners”) Approach: if contract looks complete and fully integrated, no extrinsic evidence allowed. o “Merger Clause”: stating plainly as a term that this agreement is final. (Willistonian) Modern (Corbin) (Restatement §210) Approach: finding of integration should always depend on the actual intent of the parties, and courts can use extrinsic evidence to uncover that intent. o Existence of a merger clause is non-determinative. o Hidden assumptions are that an agreement is construed according to King’s English, common sense of men. But realize you can’t do that in the modern world without taking into account full context. Parties might believe “sick” = “good”, or “dope” = “yes”, or “pwn noobs” = “win”. Conclusive presumption: final written agreement is assumed done and complete as a base. Johnson: Difference between contradiction/supplementation and interpretation is thin. Exceptions: Parol Evidence Rule does not apply to: 1. Evidence offered to interpret or explain the meaning of the agreement. a. Partially integrated agreement may be supplemented by consistent terms. b. Any integrated agreement may be explained by extrinsic terms. i. Ex: evidence of trade usage. ii. Agreements (oral or written) made after the execution of the writing. c. Course of performance argument, or argument for modification of a contract. 2. Evidence offered to show that agreement is subject to oral condition precedent. a. (Ex: “Deal, unless I don’t get the bank loan.”) 3. Evidence offered to show that the agreement is invalid for any reason such as: fraud, duress, undue influence, incapacity, mistake, or illegality. a. “Fraud in the execution”: signed the wrong thing. b. “Fraud in the inducement”: misrepresentations of fact that induce the other party into contract. 4. Evidence offered to establish right to an “equitable” remedy. a. Such as “reformation” of the contract. b. Something mistakenly omitted (scrivener’s error). c. Requires clear contradictory intent. 5. Evidence introduced to establish a “collateral” agreement between the parties. a. Collateral exception: subject distinct from that to which the writing relates. b. Restatement (Second) §216(2): an agreement will not be regarded fully integrated if the parties have made a consistent additional agreement which is either agreed to for separate consideration or might naturally be omitted from the writing. Thompson v. Libby (1885) Facts: Written agreement didn’t include warranty for log quality. Had a warranty in previous oral agreements. Issue: When can you use extrinsic evidence to supplement a contract? Rule: Parol evidence rule finds evidence inadmissible when it contradicts or varies the terms of a valid written instrument that is meant to be the entire agreement. If writing not final and complete (not integrated), consistent, not contradictory, parol evidence may be used to interpret. Parol evidence cannot be used to determine if a contract is complete; must review contract itself. Notes: Rule founded on the obvious inconvenience and injustice that would result if matters were controlled by “the uncertain testimony of slippery memory.” A warranty is collateral to a contract of sale. Notes: Four corners approach to interpretation. Supplementation of the original agreement (not interpretation). Johnson: Williston: Where the writing is incomplete on its face, it’s easy: not fully integrated because missing clear/essential terms. When ambiguity, make presumption in favor of writing being integrated. Back and forth of negotiation is excluded. Taylor v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co. (1993) Facts: P sued D for bad faith, claimed D improperly failed to settle a claim against him within his policy limits. D says P signed a release relinquished his right to sue. Bad faith release. Issue: Whether parol evidence properly admitted to interpret the release and determine ambiguity. 25 Rule: Court considers offered evidence and, if “reasonably susceptible” to the interpretation asserted, the evidence is admissible to determine the meaning intended by the parties. (Corbinian). Notes: Under Willison, ambiguity must exist before use of extrinsic evidence. Johnson: Interpretation vs. contradiction plays differently between approaches. “King’s English vs. Rapper’s English.” Reasonably acceptable standard: Was it ambiguous? Is the evidence convincing as to P’s interpretation? Is there extrinsic evidence to support that interpretation? Nanakuli Paving & Rock Co. v. Shell Oil Co. (1981) Facts: Under UCC. Hawaii asphalt company read price protection into agreement (not explicit). Contract stated price of shale would be sold at “Shell’s posted price.” Price protection was routine, customary trade practice. Rule: UCC liberal approach. Background for interpretation set by the commercial context, which can supplement even the language of a formal or final writing. Trade usage to price protect could reasonably be construed as consistent with express terms. Most important evidence is thus the actual performance of the contract. D said previous dealings was a waiver and now rescinded the waiver. But usage of trade was clear here. Johnson: Symbiotic relationship makes good faith argument stronger (relational contract theory). White & Summers (pg. 455 footnote): Usage of trade may not be well known, or even universal, just needs to be regular enough to justify one party’s expectation. UCC: departs from the common law by being more liberal in parol evidence rule. We will embrace course of trade, usage, evidence if it can be construed to work with the express terms. Only binding on parties if it can be reconciled with express terms. Under UCC, we will ignore express term as dominant piece of evidence, when trade usage/course of dealing/performance evidence is more probative as agreement between parties. If the express terms had said no price protection, then the case is obvious. But if not explicit, we can write the price protection in. This allows you to push the interpretation envelope. Obligation of good faith and fair dealing: fair for jury to conclude that reasonable commercial standards would demand proper notice; price protection is about notice. Requirements contract: a contract in which one party agrees to supply as much of a good or service as is required by the other party, and in exchange the other party expressly or implicitly promises that it will obtain its goods or services exclusively from the first party. UCC §2-202: Negation of Johnson’s Pyramid would require explicit language outside the boilerplate, long hand description. Very hard to disclaim these without being very descriptive. X. IMPLIED TERMS Implied-in-law: new terms made a part of the agreement by operation of law (courts) rather than contract itself. Implied contracts vs. implied terms o Contracts implied-in-law (fake; no real contract) based on restitution. o Terms implied in law (gap-fillers) are fake too, but come from a real desire to facilitate transactions. Wood v. Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon (1917) Facts: Fashionista (D) gave P exclusive right to sell and market her designs. She breached by entering into new agreement. D claimed contract illusory because no obligation listed under contract. Rule: Implied obligation to use reasonable efforts will prevent a somewhat indefinite promise from being illusory. Without implied term, the transaction can’t have business “efficacy as both parties must have intended.” As a matter of policy, court tilts away from illusory to implying term of exclusivity and duty to perform. Equity is recognition that pushing your facts into a square peg can lead to fairness issues. Implied terms serve our purpose of keeping parties together. Johnson: Minimum value of this case: it only applies to exclusivity contracts. Broader value: imposition of reasonable/best efforts beyond exclusivity. What is the line of efforts? Court built on this risk and said, when someone involved in this type of arrangement where one side can choose how to perform, and the other relies on them doing well, then we imply a term on party with discretion, that they behave reasonably, or best way possible. We’re really just groping around for terms without real guidance. UCC advances exclusivity. But does the code really demand exclusivity under 2-306? No, not a literal requirement. NOTE 3: courts more willing to incorporate implied term if exclusivity. 26 UCC §2-306: Instead of “reasonable efforts”, calls for “best efforts.” Best efforts is subjective. Reasonable effort is objective; determined by the market. Which seems more demanding? Exploit this. Gap-filling Provisions of UCC Article 2 “Off-the-rack terms” o 2-308, place of delivery o 2-310, time of payment o 2-509, risk of loss o 2-513, buyer’s right of inspection Usually subject to preemption by express terms, but some are mandatory. Justified by fairness and probable intention of the parties; economic efficiency. Default rules: reflect a hypothetical bargain. o If more informed party excludes implied terms strategically, court may impose “penalty default rules”. Distributorship Agreements of Indefinite Duration Governed by UCC. Termination of indefinite (at will) contracts requires reasonable notification. UCC §2-309: Reasonable Notice Factors Distributor’s need to sell off remaining inventory. Whether this is an unrecouped investment made in reliance on agreement (return “on” investment). Whether this is a return “of” investment. Sufficient or “reasonable time” to find a substitute arrangement. Terms in present or prior agreements. Type of business (some goods sell faster). Spectrum of time. Some courts won’t enforce agreements of indefinite duration if duration is vital to contract. Leibel v. Raynor Manufacturing Co. (1978) Facts: Deal between dealer-distributor selling garage doors. K lists this as a sale of services (really it’s goods). Issue: Was this a sale of goods? Was notification of termination reasonable under the circumstances? Rule: Reasonable notice required to terminate ongoing oral agreement for sale of goods in a dealer-distributor relationship. Application of UCC not avoided by merely writing in: “sales distribution plan”. 3 options when time isn’t specified: forever, at will, or reasonable length. Johnson: What’s the alternative story? How would Code not apply (what labels should we use)? Characterize the relationship as a salesman (based on commission): “Independent contractor salesman”. Seller must change behavior to match what document says. You can write all you want. But what actually happens? What factors would we tell client they should change to make document have higher probability of enforcement? Inventory. What about Pyramid scheme sellers? XI. GOOD FAITH Often easier to think of what bad faith is. o Good faith (not a separate cause of action) is merely an “excluder” of bad conduct. o Bad faith injures the “spirit” of the contract. Johnson Criticism: don’t really need good faith to enforce (fraud, duress, failure to mitigate (damages), etc. UCC already provides policing options. Good faith to protect the “fruits of the contract” Bad faith by one party to capture “foregone opportunities”. 27 Generally preventing “opportunistic behavior”. UCC §1-304: Every contract or duty within its scope imposes an obligation of good faith in its performance and enforcement. 2nd Restatement §205: Extends duty of good faith and fair dealing to every contract. Seidenberg v. Summit Bank (2002) Facts: D fired P after acquiring P’s company. P alleges breach of implied covenant of good faith; claims D was never committed to developing business with P, just wanted to acquire business. Rule: Parol evidence rule cannot be applied to prove breach of good faith because good faith is an implied, not express, term. Good faith covenant permits: 1) inclusion of terms which have not been expressly included in the contracts, 2) redress for bad faith performance even when D hasn’t breached any express term, and 3) inquiry into party’s exercise of discretion expressly granted by a contract’s terms. Notes:: Presence of bad faith is found in the eye of the trier of fact. To determine a breach of good faith, a court must allow parol evidence. Johnson: Concern that too much policing under good faith will disrupt bargaining. But we do want to file a warning shot with cases along the edges. Sons of Thunder v. Borden Analysis: Implied covenant of good faith could not override the express right to terminate, but also held that D could have breached the implied covenant of good faith before exercising the right to terminate. Johnson: Acted lawful, but wrongful. Most vigorous refutation of parol evidence rule we’ve seen. UCC approaches “good faith” with caution; courts have moved toward giving express terms near absolute priority, rendering the implied duty of good faith irrelevant in many situations. A. Requirements and Output Contracts When parties leave quantity of goods to be delivered open/flexible. (Sometimes seen as illusory.) Requirements contract: seller will supply all goods that the buyer may require during the term of the contract. o Breach if buy from someone else. Output contract: buyer obligated to buy all the seller’s output. o Breach when seller sells to someone else. Initially were called illusory, too indefinite, not mutual, no consideration. Consideration problem solved because party either buys from that seller or not at all (gives up a right). o Under UCC, if agreement does not bind the buyer to buy only from that seller, likely to be viewed as invalid and unenforceable. Not totally clear how breach of requirement contract is established; reduction in need probably in good faith if it results from something beyond the buyer’s control. How to avoid abuse via good faith dealing? o Focus on how to avoid clear breaches. Require exclusivity. Require all output from seller to be purchased by buyer. How to avoid abuse when change in market conditions? UCC 2-306: good faith requirement concerning output and requirements contracts. Allows exit for disproportionate departure from a stated norm: a factual judgement. XII. WARRANTIES Contrast idea of implied warranties with the historical norm of caveat emptor. UCC §2-313: Express warranties (what you negotiate for). Seller may provide the basis for an express warranty by making a representation about the goods, giving a description, or displaying a sample or model. Puffery vs. verified statements. UCC §2-314: Implied warranty of merchantability: a merchant who regularly sells goods of a particular kind impliedly warrants to the buyer that the goods are of good quality and are fit for the ordinary purposes for which they are used. Must determine seller is a merchant with respect to the goods sold. Tests: 28 Ex: Big Lots buys surplus inventory and sells at bargain prices—do you claim particular knowledge in regards to that product? Do you specialize in this item? Are you a merchant in regards to this item? If so, this implied warranty of merchantability applies to you. UCC §2-315: Implied warranty of fitness for a particular purpose: created only when the buyer relies on the seller’s judgment to select suitable goods and the seller has reason to know of this reliance. Breach requires showing that the goods are not fit for the buyer’s particular purpose. Not limited to merchants Was reliance legitimate? Look at surrounding circumstances. Uniform Sales Act §14: implied warranty in sale by description §15: implied warranties of quality §16: implied warranties in sale by sample Uniform Residential Landlord Tenant Act: Warranty of habitability: landlord must comply with applicable building and housing codes affecting health and safety. Bayliner Marine Corp. v. Crow (1999) Facts: Bayliner boat sold with many modifications; didn’t perform the same way as base model. Rule: To prove a product is not merchantable, the complaining party must establish the standard of merchantability in the trade. Fact-intensive analysis required. None on record here. P failed to prove that the boat “would not pass without objection in the trade.” Implied warranty of merchantability: look at whether seller is merchant in goods of that type (whether they sell them with regularity or whether they claim some specific knowledge). No proof that boat wasn’t able to be used for the offshore fishing purpose. Implied warranty of fitness for a particular purpose: focus on how client failed to fully articulate purpose. On flip side, tell story about how seller was familiar with nearby fishing waters and knew about what client’s purpose would have been. Under UCC 2-313, a statement that’s merely the sellers opinion is not a warranty – this was just a comment on the boat’s performance, it doesn’t describe the boat’s specific characteristics. Notes: Disclaimers of express warranties allowed. Merchantability and fitness can both be disclaimed. Johnson: Should’ve gotten an expert in the trade to testify (trade association) and discuss documents that show that this is standard of the trade. Everything that you want to put into evidence needs to be testified to by expert. Was reliance legitimate? Look at surrounding circumstances. Speight v. Walters Development Co. (2008) Facts: P third owner of a house with defective roof. Sued builder D. Issue: Whether remote purchasers can pursue claim for breach of implied warranty of workmanlike construction. Rule: The purpose of the implied warranty of workmanlike construction is to ensure that innocent home buyers are protected from latent defects. Equally applicable to subsequent purchasers who are in no better position than original purchasers. Lack of privity does not preclude recovery. Notes: Court recedes from the doctrine of caveat emptor; latent defects are undiscoverable for some time. Implied warranty is a judicial creation and does not itself arise out of the language of any contract. Many jurisdictions don’t apply this warranty to subsequent purchasers. Lack of contractual relationship (privity). Purpose of the warranty/public policy: o Bargaining Power: subsequent buyers aren’t in a better position than original owners to discover latent defects. 29 o o o To ensure that home is “fit for habitation” depends on the quality of the home, not the status of the owners. Society increasingly mobile; homeownership likely to change; this would be injustice; unequal bargaining power between builders (experts) and buyers. Builders aren’t any more exposed to suit than originally; same SOL. If the first buyer sells the house after a year, the builder is no longer liable and this isn’t fair. Implied warranty of workmanlike construction: (judicially created doctrine) to protect an innocent buyer by holding the builder accountable for the quality of construction. Due to unequal bargaining power/knowledge between builder and purchaser Implied warranty in the sale of a new home: (could be called workmanlike construction, merchantability, habitability, etc.) Courts make two distinctions: 1) habitability (suitable for occupation), 2) workmanlike or skillful construction. (reasonable standards of quality of work and materials). AVOIDING ENFORCEMENT: BASKET OF CREEPY CASES XIII. MINORITY & MENTAL INCAPACITY A. Minority (Infancy) Traditional minority doctrine: return and full reimbursement is completely at the choice of the minor (voidable). Modern minority doctrine: o Benefit rule: upon rescission, recovery of the full purchase price is subject to a deduction for the minor’s use of the merchandise. o Depreciation rule: recovery of full purchase price is subject to a deduction for the depreciation or deterioration of consideration in his possession. Dodson v. Shrader (1992) Facts: Minor wants to cancel contract for pickup truck. Pickup truck engine blew up and car hit it, reducing value to $500 in 9 months of ownership. Refund refused. Rule: Where the minor has taken and used the article purchased, he can recover the amount paid after allowing the vendor reasonable compensation for the use of, depreciation, and willful or negligent damage to the article. Johnson: Protection of minors but also handicaps them; adults won’t want to sell to minors with these protections! We won’t allow minors to void contracts for “necessaries” because contrary to how we want them to be used (nobody would sell to minors). If contract voidable, and reaches age of majority, and doesn’t act in reasonable amount of time, then implied ratification. Avoidance of employment contract provisions: courts divided. Courts split over whether at age of majority, minor can disaffirm agreements made by parents. Emancipated minors subject to contract law. Courts split over liability if minor misrepresented age. B. Mental Incapacity Mentally incapacitated required to make restoration to the other party unless special circumstances. Other party can’t easily find out if someone is mentally incompetent, so statutes impose limitations; usually, if one is under guardianship, can’t enter into contracts. Tests for mental competency: o Traditional (Cognitive) (True) Test: party incapable of understanding and/or deciding on terms and consequences. o Modern (Effective) (Volitional) Test: party unable to act in a reasonable manner. Courts struggle to define behavior/phenomena causing us to say contract is unenforceable. Consider mental state at time of transaction. Restrictions used to also include married women, racial minorities (protection or oppression). Infancy vs. Mental Incapacity: must investigate age; no excuse unless misrepresentation. Excuse if incapacity unknown and incapacitated trader must make restitution. Sparrow v. Demonico (2012) 30 Facts: Dispute over family home. Settlement with voluntary mediation to give part of profit to wife after selling home. Husband testified that wife had a mental breakdown. Layperson evidence of distress. Rule: Innovation: long-term mental illness not necessary, it can be momentary and undiagnosed. Evidence that comes from laypeople still not good enough; we require professional medical testimony to prove even temporary mental incapacity. Johnson: Do we want to create a wider sphere of incapacity so adults would be afraid to deal with each other for future revelation of unseen incapacity. Not an excuse not to know they’re not an infant (unless misrepresented). Default rule to investigate. but what about incapacity? Would we have to place a duty on everyone to figure out/discover incompetence first. 2nd Restatement §16: Intoxication Contract voidable if party has reason to know that other party is intoxicated and is unable to either understand the transaction or act reasonably. o Johnson: We wrestle with cocktail parties to encourage people to buy a car, for example. Hypotheticals If you’re emancipated, who will deal with you contractually if still a minor, if outside necessities? This person is in a spot where essential to trade as an adult. Can you be partially/temporarily emancipated? What about incapacitated minor? Minor dealing with an incapacitated person? What about incapacitated and emancipated? XIV. DURESS & UNDUE INFLUENCE A. Duress Contracts made under economic coercion are voidable. 2nd Restatement §175: economic duress requires three elements: 1) wrongful or improper threat (need not be illegal), 2) lack of reasonable alternative, 3) actual inducement of the contract by threat. Comment B: Reasonable Alternatives: availability of legal action/remedy, alternative sources of goods, services or funds, toleration of the threat if only a “minor vexation.” Totem Marine Tug & Barge Inc. v. Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. (1978) Facts: Totem transporting materials. Alyeska makes it extra hard for Totem. Settlement under duress because needed money to pay debts incurred doing work for Alyeska. Accepted low settlement to avoid bankruptcy. Issue: Economic duress? What was the coercive act? Rule: Economic duress exists when: 1) wrongful or improper threat (need not be illegal), 2) lack of reasonable alternative, 3) actual inducement of the contract by threat. Contracts made under economic duress are voidable, not void. Alternative not reasonable if delay causes irreparable loss. Why is a settlement a contract? Settlement = consideration: give up claims in exchange for money. Notes: What happens on the margins? If someone enters into a contract only because going bankrupt (not pressure on purpose) and later wants to rescind it because no longer in dire straights? Taking advantage? Notes: A party’s use of increased bargaining power, resulting from dramatic changes in the market, does not amount to economic duress. Threat of criminal proceedings is clearly wrongful. Sometimes knowing about and exploiting a hardship is a surrogate for creating it. Unless the party caused the hardship, fact that someone has no choice but to work with them is not undue influence (most courts). 31 Johnson: What is duress? We can feel it naturally. We are looking for a pile up of circumstances that make P look sympathetic and D look like a nasty SOB. Is it possible to engage in a contract whose terms seem reasonable if it’s also true that you have no alternative but to enter into the agreement? B. Undue Influence Use of excessive pressure by a dominant party in overcoming the will of a vulnerable person. o Often a special relationship is a significant factor in a court’s assessment. o Hallmark of duress is overpersuasion; no threat; it’s almost friendly. o Contracts made under undue influence are voidable. Factors indicating undue influence: 1) Discussion at an unusual time. 2) Consummation at an unusual place. 3) Demand the business be finished immediately. 4) Extreme emphasis on negative consequences of delay. 5) Multiple persuaders against single party. 6) Absence of third-party advisors. 7) Statements that there is no time to consult financial advisors or attorneys. Statements that there is no time to consult financial advisors or attorneys. Odorizzi v. Bloomfield School District (1966) Facts: Teacher arrested on charges of homosexual activity; after being arrested and held in jail for 40 hours without sleep, school principal and superintendent came to his house and advised him to resign. Rule: Where excessive pressure is used to persuade a party in a weakened mental state, so that the dominant party’s will replaces the servient party’s, the agreement may be rescinded as obtained by undue influence. Seven Factors accompanying undue influence (above). Moore v. Moore: Husband just murdered and she’s pregnant. She is certainly vulnerable to undue influence. Reasonable deal, but still unduly influenced. Johnson: Confidential and fiduciary relationships very susceptible: Doctor-patient, lawyer, trustee, family. Cadillac fetish known by doctor who induces patient to buy a Cadillac. Can an ordinary, non-susceptible, person be vulnerable to undue influence? Yes. If you are in a tough spot; your ability to say no is overcome. Notes: Could be lawful but still wrongful threat. Didn’t meet CA duress standard in 1966, merely undue influence. XV. MISREPRESENTATION & NONDISCLOSURE A. Misrepresentation Remedy for misrepresentation is rescission. Rescission: judicial return of the parties to the status quo that existed before the contract was formed. o For legal rescission, tender must first be given. Victim of misrepresentation has choice between: o Tort action for damages. No need for return of property, just damages. o Right to avoid the enforceability of the contract by way of rescission. Requires victim to return any money or property received. Distinction between statements of opinion and representations of fact: o Classical rule: statement of opinion could not be fraudulent (allows for “puffing”). Zumba high-five example. Are you actually good at Zumba? Why is that different? 2nd Restatement §161: a party may rescind a contract for a material misrepresentation even if the misrepresentation was not made with fraudulent intent. 2nd Restatement §169: Statement of opinion can be misrepresentation if false. Opinion may also be actionable if opiniongiver: 1) stands in a fiduciary relationship with other party, 2) is an expert in the matter, 3) renders opinion to one particularly susceptible. 2nd Restatement §164: Contract voidable if a party’s manifestation of assent is induced by a fraudulent or material misrepresentation by the other party relied upon. 32 2nd Restatement §162: “Fraudulent” can also include statements made recklessly or negligently. Syester v. Banta (1965) Facts: Predatory selling of dance lessons to old woman. D planned divertive campaign to get her to drop suit. Rule: Fraudulent inducement; misrepresentation. Jury instructions for finding fraud: o Did D make one or more of the representations claimed by P? o Were said statements false? o Were the statements in reference to material matters? o Did D known the representations were false? o Were said representations made with intent to deceive or defraud? o Did P believe or rely upon these false representations? o Was P damaged due to this reliance? Analysis: D argues mere expression of opinion, or “puffing”. Misrepresentation standard requires material misrepresentation that induced other party to enter a contract. Johnson: “This case smells to high heaven.” Pufing/Statements of opinion (expression of belief, without certainty, as to the existence of a fact) vs. representation of fact. Normally court would find her willingness to sign unreasonable, but she was unique. Fraud is more for courts of law, unconscionability is for courts of equity. But as things get creepier, solid concepts like fraud become as mushy as unconscionability. Long con: Signed a release which actually turned out to be a promissory note. D said doc was just a mistake. But knew he could collect on her estate when she died. B. Nondisclosure (Silence) Classical view: cannot avoid transaction because of nondisclosure of material information by the other party; duty to investigate for oneself. Modern view: nondisclosure of a material fact may justify rescission of a contract. Party only has an obligation to affirmatively disclose material facts when: o Disclosure is necessary to prevent a previous assertion from being a misrepresentation or from being fraudulent or material. o Disclosure would correct a mistake of the other party as to the contents or effect of a writing. o Disclosure would correct a mistake of the other party as to a basic assumption on which that party is making the contract and nondisclosure amounts to a failure to act in good faith. o Fiduciary relationship between parties. (Terms must be clear and fully explained.) Rescission is the relief when the nondisclosure amounts to a failure to act in good faith and with fair dealing. Factors to consider: o Differences in intelligence of the parties. o Relationship (fiduciary relationship of trust and confidence? Mere friendship?). o Manner in which the info was acquired (chance or effort). o Whether the nondisclosed fact was readily discoverable. o Whether the person failing to make disclosure was the seller rather than the buyer. o Type of contract (disclaimers? insurance release?). o Importance of the fact not disclosed. o Whether active concealment occurred. Stechschulte v. Jennings (2013) 33 Facts: D purchased home with water leaks, made bandaid fixes, resold house. and did not represent in disclosure addendum that there were leaks. After storm, major leaks came to light. Rule: Seller may not avoid liability by claiming buyer signed off on a form on which seller intentionally misrepresented information. Disclaimer of statutore obligation not going to be upheld. Elements of fraudulent inducement: 1. D made false representations as a statement of existing and material fact. 2. D knew the representations were false or made them recklessly without real knowledge. 3. D made representations intentionally to induce another part to act upon them. 4. Other party reasonably relied/acted upon the representations. 5. Other party sustained damages. o A representation is material when it relates to some matter so substantial as to influence the party to whom it is made, Fraud by silence: D had knowledge of material facts that P did not have and could not have discovered through reasonable diligence. D was under an obligation to communicate the material facts to P. D intentionally failed to communicate to P the material facts. P justifiably relied upon D to communicate the material facts. P sustained damages. Negligent misrepresentation: Person supplying the false info failed to exercise reasonable care or competence in obtaining or communicating the false info. Person who relies upon the info is the person for whose benefit and guidance the info is supplied. The damages are suffered. Johnson: Would inspector notice this problem? No. Obligation for D to disclose. Concealment piece of fraud. Also, fraud by silence. Look like the same thing. Notes: Classical view that duty of buyer to make sure they’re not screwed; rugged individualism. 2nd Restatement §173: where fiduciary relationship exists, duty of disclosure, and terms of transaction must be fair and fully explained to the party. Elements of actual fraud: D knowingly made false representations to P. Representations were material to contract. Representations were made with intent to deceive and defraud. P believed and reasonably relied upon false representations to her injury and wouldn’t have entered the contract without them. Types of fraud: (“Fraud vitiates every transaction.”) Fraudulent inducement Fraudulent concealment (cover up) Fraud by silence (fraudulent nondisclosure) Negligent misrepresentation o Probably won’t go to jail for this. Careless misrepresentation is less serious than intentional misrepresentation. Get to unwind the contract. Misrepresentation of material facts Fraud in the execution Breach of contract C. Fraud in the Execution When party alleging fraud was misled as to nature of the writing before signing. Fraud in the inducement: party knows what he is signing but does so as the result of misrepresentation. 2nd Restatement: in a case of fraud in the execution, court may reform contract to express terms of agreement as asserted if the recipient was justified in relying on the misrepresentation. Park 100 Investors, Inc. v. Kartes (1995) 34 Facts: P caught Ds on their way to daughter’s wedding rehearsal dinner, gave them “contract” to sign; it was a personal guaranty of their lease. D didn’t read before signing, but fraud overcomes duty to read only because D’s behavior in the circumstances was reasonable (D called lawyer) and there was misrepresentation. Rule: But where one employs misrepresentation to induce an obligation under contract, one cannot bind the party to said terms. Silence is a fraudulent omission of material fact. Johnson: Slipping additional document, or lying about what it means, is all fraud in the execution. Called and asked lawyer before signing. Told it was fine to sign because he thought it was the original agreement. What if they couldn’t get in touch with lawyer? What if it was just one page, properly titled? How does the tight time (late for daughter’s wedding) affect the argument? Duress? Not really. Maybe undue influence? Incapacity? We must square fraud in the execution with the duty to read (Eurice Bros). 2nd Restatement §166 (Fraud in the execution): If a party’s manifestation of assent is induced by other party’s fraudulent misrepresentation as to the contents of the writing, the court may reform the writing to express original terms. Defense to “duty to read” argument. Johnson’s publisher agreement: Johnson deleted provision in Word, signed and sent back. Didn’t disclose change to them. Bargaining power? Expertise? Size of publisher? Significance of deletion? Do they expect you to make changes? Did both sides sign the document? What if only a space for Johnson’s signature? o Is letterhead enough? Duty to read? Against the original drafter? Fraud in the execution? Concealment? Adhesion contract? Sent in Word, not PDF. No gamesmanship between lawyers here. XVI. UNCONSCIONABILITY Vague catch-all for creepy cases that are “grossly unfair,” “monstrously inappropriate,” or “shocking to the conscience.” Procedural unconscionability: lack of choice by one party or some defect in the bargaining process (such as quasi-fraud or quasi-duress). Substantive unconscionability: relates to the fairness of the terms of the resulting bargain. o Courts generally require a showing of both; don’t have to be to same degree. Williams v. Walker-Thomas Furniture Co. (1965) Facts: Store sold furniture and other items door-to-door to poor people on credit, used confusing add-on clause saying if customer defaulted on one payment, every item they had ever purchased was repossessed. Rule: Where the element of unconscionability is present at the time a contract is made, the contract should not be enforced. Unconscionability defined as absence of meaningful choice on the part of one of the parties together with contract terms which are unreasonably favorable to the other party. Sometimes due to gross inequalities in bargaining power. Notes: Court seems to argue that real problem is selling to someone you know is poor. Consider the terms in light of the general commercial background and the commercial needs of the particular trade or case. 35 Intrinsic fraud: a bargain that no man in his senses and not under delusion would make and no honest and fair man would accept. Johnson: Should the doctrine apply to major terms consumers usually do focus on, like price? Does unconscionability only apply to the chronically poor? We think differently if someone is well off but down on her luck. Any social policy justification for allowing the company to operate this way? Maybe she saw this as an opportunity (to make money on the stereo). After this case, poor will not be able to get credit at all; overprotected. Neighbors knew about this guys reputation. Should she have? Uniform Consumer Credit Code §5.108: multifactor balancing approach, assessing unconscionability: Whether the seller believes that consumer likely to default Whether the consumer will receive substantial benefit from the transaction Gross disparity between the contract and market price Whether the seller knowingly took advantage of a consumer’s bargaining impairment due to mental impairment Lack of education Other similar factors (Kansas): o Use of a standard form contract o Limitation on available remedies for breach o Use of inconspicuous or incomprehensible terms o Overall imbalance in the bargain o Inequality of bargaining and economic power UCC §2-302: Unconscionability is a legal question for the court after evidence collected. Used by some to find unconscionability due to excessive price. Unclear if writers intended this. Higgins v. Superior Court of LA County (2006) Facts: Extreme Makeover Home Edition. Orphaned siblings kicked out of house built for them. Arbitration provision prompts the unconscionability discussion. Court is affected by overarching “creepiness.” Rule: Arbitration clause is unconscionable. Nothing in the agreement brings the reader’s attention to the provision. Procedural unconscionability focuses on oppression and surprise due to unequal bargaining power. Substantive element focuses on overly harsh or one-sided results. Both must be present to find unconscionability. But not in the same degree. Entire arbitration clause was itself one-sided; only plaintiffs have a duty to arbitrate. Contract of adhesion; presented as take-it or leave-it. Notes: Adhesion contracts usually satisfy procedural unconscionability. Substantive unconscionability usually includes prohibitive arbitral cost and lack of bilateral application. Johnson: We care about unconscionability in arbitration agreements. Really these kids were exploited due to nature of contract, more so than the arbitration clause. Opinion: Arbitration clauses should only apply to commercial use. Arbitration Agreements Many courts have held that arbitration agreements may be substantively unconscionable if excessive costs of arbitration effectively preclude claimant from pursuing relief. Some have also held that arbitration agreements need to be bilateral. In modern era, default arbitration provisions are very common. Advantage of arbitration for large companies: no precedent established if they lose. Quicken Loans, Inc. v. Brown (2012) Facts: P sees popup ad online for Quicken refinancing. Very predatory home loan and lie about ability to refinance later. Closing docs signed without Quicken rep and in tight timeframe. No opportunity for questions. Balloon payment: huge lump sum. State statute says that if a lender offering balloon payment, must be conspicuously disclosed. If not disclosed, then probably fraud. Rule: Fraudulent concealment: concealment of facts by one with knowledge, duty to disclose, coupled with intention to mislead. Unconscionable: unfair bargaining power, completely one-side, and no alternative/choice. Johnson: “Unconscionable because it’s unconscionable” – circular definition. The real message is that this is factdependent. Why pursue both fraud and unconscionability? Fraud requires intent; hard to prove. Unconscionability 36 requires subjective fact-based arguments. Does unconscionability only apply to poor people? Typically we look for imbalance in bargaining power, without that, hard to prove. For fraud you must prove reliance on the misrepresentation; hard to do if P didn’t understand the terms at all. XVII. PUBLIC POLICY Restraint on trade vs. freedom of contract. 2nd Restatement: preserves CL rule that a covenant not to compete is unenforceable unless it only supplements a valid transaction (i.e. more likely upheld for sale of business than employment). Valley Medical Specialists v. Farber (1999) Facts: Doctor worked for corporation, then left to practice on his own; P sued to enforce restrictive covenant that would have prevented him from practicing in a 235-square-mile area for three years. Rule: Non-compete covenant must be strictly scrutinized for reasonableness: 1) reasonable as to time, place and scope, 2) hardship on promisor, 3) public interest. Public policy interest in doctor-patient relationship; Court wants to preserve patient choice. Consider amount of time needed to make sufficient contacts with customers to solidify relationship. Some professions present a more significant policy question (lawyer, doctor). Johnson: What if I sell my business, then open the same business across the street? Not cool – want to protect against this. Contracts in restraint of trade generate harm if too broad (over protective) and too specific (not protective). When selling your business, you’re selling your goodwill – client base and relationships. Severance: court endorsed “blue pencil,” mechanical reduction of an objectionable covenant if the term can literally be crossed out and the remainder enforced. Restatement rejects mechanical approach, endorses more flexible method that allows reduction of the scope of a clause to make it reasonable. May incentivize people to engage in overreaching conduct. NONPERFORMANCE If for one of the parties a circumstance not expressly provided for in the contract has adversely affected either performance itself or the value thereof, should that party be permitted to escape an obligation of performance? XVIII. MISTAKE A. Mutual Mistake Ordinary remedy: rescission. Buyer and seller can unwind a contracts based on mutual mistake, not unilateral. Look for area where initial description is proved to be false. “Fine cow” vs. “breeding cow” vs. “barren cow” o What if you get home and the cow is actually a donkey? Mutual mistake; rescission. o Buy painting and find out it’s worth $5M later. Described as by one artist. But really by another. Unwind. But if never described as by a different artist, or just as “a painting” no mutual mistake. Mutual mistake generally does not encompass mistakes as to value, only substance (essence). o Ultimately an illusory distinction; can’t disassociate these two. Mutual mistake does not apply when general description at time of sale is contradicted by later rise in value. 37 o E.g., if “car” sold for $5,000 but later turned out to be “JFK’s car,” description of “car” is still accurate, doesn’t contradict On the other hand: Barren Cow (Sherwood v. Walker) o Sale was for x (“barren cow, worth $5”), party sold y (“pregnant cow, worth $100”) deal can be unwound because y directly contradicts x. But if description generic (“cow for $5”), then no unwinding. Sherwood Rule: When a mistake only affects the quality or value of the bargained-for exchange, and not the essence of the thing, no basis for relief. Lenawee County Board of Health v. Messerly (1982) Facts: Purchase of a revenue-generating rental property. Land can’t support required septic system. Worthless after leak. Rule: Essence vs. value distinction removed. Rescission not available to party who assumed the risk of loss in cases of mistake by two equally innocent parties. P assumed risk with “as is” clause. Always look for risk-allocation provision. Johnson: Some court says distinction between essence and value, but there is none; they’re intertwined. But use this analysis before debunking. Value: maybe cow isn’t as fertile as thought. Essence: barren/fertile cow at all. Argue this is clearly a mistake as to essence, then explain what was contracted for and what was ultimately transferred. To resolve a mutual mistake problem, ask did after-acquired info make earlier information false? Notes: “As is” clause not uniform across jurisdictions. Phrase is so ubiquitous that it is no longer seen at all. As is, or time is of the essence don’t have concrete meanings anymore. Starts as customized provision, then so ubiquitous as to be white noise. Then looks more boilerplate, and we underenforce. Then pendulum swings back to being fact-specific. If these terms are considered in negotiations, more weight. Conscious ignorance; assuming the risk by ignoring pertinent facts (2nd Restatement §154). Mutual mistake in writing. B. Unilateral Mistake Old rule: granting relief for unilateral mistake required that mistake be “palpable”: so obvious that other party knew or should have known that a mistake had been made (can’t snap up an offer that’s too good to be true). Rescission will permitted for clerical errors or other mistakes of fact, but not for mistakes in judgment. Negligent unilateral mistakes: o Many courts have held that unilateral mistakes must be non-negligent, but clear tendency to relax requirement where proof of mistake is strong and effect of enforcement will be devastating. o Restatement expressly negates non-negligence requirement. Restatement requires either: 1) Mistake is such that enforcement of contract would be unconscionable (severe enough to cause substantial loss), or 2) Other party had reason to know or was responsible for causing the mistake. 2nd Restatement §153: granting relief for unilateral mistake. DePrince v. Starboard Cruise Services (2015) Facts: P wants to buy diamond. Quoted outrageously low price. Despite “too good to be true” warning by partner, buys anyway. Seller’s supplier imprecise in describing the price (per carat rather than total). Rule: Defense of unilateral mistake requires evidence that the breaching party did not act negligently or without due care. How we treat unilateral mistakes is evolving. Three tests to use, all examine: conduct of the party seeking to enforce the contract (did he know of the mistake?), 2) conduct of the party claiming relief from mistake, and 3) extent to which enforcement would be unjust or unconscionable. Notes: In the past, no relief for unilateral mistake unless other party knew or should have known. Now, courts are more generous re: unilateral mistake. Some jurisdictions look for “palpable mistake”: other party knew or had reason to know about mistake of other party. Johnson: Mutual mistake claim is far easier to sustain, and precedentially deeper, than the unilateral mistake claim; new kid on the block. Drennan and Baird: In Baird argument between GC and SC asking for rescission by unilateral mistake, vs. Drennan argument of reliance. Which doctrine should trump? We might tilt in favor of Drennan argument because of change in status of GC due to reliance. Unilateral mistake in advertising. You 38 might lose ad as an offer argument if it’s explicit enough to be treated as an offer. Could still escape performance if someone else makes the mistake; if publisher made the mistake. Unless duty to read the copy/approve/etc. XIX. IMPOSSIBILITY, IMPRACTICABILITY, & FRUSTRATION Changed circumstances treated as questions of law for the judge, rather than fact for jury to decide. Low-probability moves; unlikely to win these cases. Literal impossibility most likely to win, but still not very strong. o Personal services contract: Picasso enters into contract to paint family portrait. He died and obligation dies with him. o Not personal services: What if Picasso has mortgage and dies? Wife still liable. Somebody has to pay. Impossibility Requires showing literal impossibility (objective). Includes prohibition of performance by government action. o Not whether you can perform, but whether it can be performed. When a person or thing necessary for performance of the agreement dies or is incapacitated, destroyed, or damaged, the duty of performance is excused. o Often doesn’t apply to fungible items. Usually for unique goods/things. Objective/literal Impossibility: no one could do it; excuses performance. o Taylor v. Caldwell: music hall burned down, performance of contract to rent it out excused. Subjective Impossibility: “I cannot do it” does not excuse. o Just because performance became difficult or more expensive, no excuse. Frustration of Purpose Exchange called for by contract has lost all value to D because of a change in extrinsic circumstances. o Krell v. Henry: rent room overlooking coronation path. King becomes ill, room rental worthless. Exists in theory, hard to find cases; some overlap with mutual mistake. Impracticability Even though performance is not literally impossible, it was sufficiently different from what parties had both contemplated at time of contracting as to be impracticable. o Performance becomes really, really expensive. Mineral Park Land v. Howard: gravel removal would cost 10-12x original anticipated cost. Most courts have refused to grant relief under impracticability or frustration to avoid a contract that has become more expensive or less profitable (unless extreme) or because of a natural disaster. For terrorism, impracticability is a rare scenario, also looks a lot like impossibility. Foreseeability: some courts have held that relief under impracticability and frustration should not be denied simply because the event may have been foreseeable. 2nd Restatement §261: to claim impossibility, a party must demonstrate: 1. Supervening event prevented promised performance and made it impracticable. 2. Nonoccurrence of the event was a basic assumption on which the contract was made. 3. Impracticability resulted without the fault of the party seeking excuse. 4. Party has not agreed to perform in spite of impracticability that would otherwise justify nonperformance. Comment D: requires reasonable effort and diligence. 2nd Restatement §262 & 263 / UCC §2-613: Performance only excused if a person or thing necessary for performance dies, is incapacitated, or is destroyed Impossibility and impracticability. Waddy v. Riggleman (2004) 39 Facts: P entered into a contract to purchase land requiring D to convey title clear of all defects. Attorney failed to timely secure two mortgage releases by the closing date so D backed out of the agreement. Rule: The doctrine of impossibility may not be used by a party to avoid a contract unless he took virtually every action within his power to perform the duties required by the agreement. Analysis: To claim impossibility, see Restatement factors above. Performance is not excused simply because a responsibility required by the contract is more difficult than expected. A party should use reasonable efforts to overcome obstacles to perform as required by the terms of the agreement. D cannot place himself in a position to be unable to perform the sale and then plead inability to perform as an excuse for their non-performance. P cannot rely on the time-is-of-the-essence clause in the contract to excuse performance. Notes: Some courts require unforeseeability, lack of fault and no assumption of risk to determine impracticability. Economic analysis: best cost avoider should bear the risk, if risk not already allocated in the contract. Johnson: Example of party manipulating impossibility doctrine to get out of a contract. Look for extraordinary difficulty. Market failure? No. Natural disaster might work, but it might not. Terrorism: maybe, not a slam dunk. Courts are stingy with impracticability. Problem must not be your fault. Frustration of purpose. Mel Frank Tool & Supply, Inc. v. Di-Chem Co. (1998) Facts: D leased property from P to store chemicals. Some considered “hazardous material.” Lease required P to comply with all city ordinances. City later inspected the premises and determined violation of the city’s fire code. D informed P that it would be relocating due to the city’s limited, although some chemicals would still be allowed. Rule: A party is not excused from performance unless the law or ordinance completely restricts use to purposes otherwise allowed under the lease. Performance must be rendered virtually worthless by government restriction to find frustration of purpose. Parties can contract to include force majeure clauses. If traffic regulations make gas station lease less profitable. Too bad. What’s the unexpected event that would ruin your contract? Johnson: Reduction in value must be VERY significant for frustration of purpose. Frustration easy if can’t use space at all. Mutual mistake is similar: If lease said this is a lease for exclusive storage of hazardous material, then can’t use for that purpose, mutual mistake. But may even be impossibility. Seems like implied warranty for a particular purpose (UCC). PUSH HARD on all of these options. Contract around them. XX. MODIFICATION Modification of a preexisting contract is always voluntary and consensual (must be mutual). Raises issues of consideration, duress, and good faith. Requiring new performance for an existing obligation is problematic. Attempt by one party to impose something on the other is not modification. o Simply trying to get more money is breach (unilateral). o Applies to employers who change benefits of employees, etc. One-sided modifications common in long-standing relationships as long as good faith maintained. 2nd Restatement: Pre-existing duty rule: new consideration is required for a modification to be enforceable; merely promising to perform an existing obligation is not valid consideration. Easy to work around: nominal consideration (peppercorn) is sufficient. Three Exceptions: o Unforeseen circumstances (solid rock unexpectedly encountered). o Reliance (PE) on a promised modification (what is sufficient reliance? Continuing original agreement?) PE reflected here. We might have a failure of consideration. o Mutual release: replacing an old contract (a raise for example). Respecting freedom of contract. As long as in good faith. UCC 2-209 gets rid of pre-existing duty rule, but allows for duress arguments. 40 UCC 2-209: Modification, Rescission, and Waiver 2-209(1): eliminates pre-existing duty rule except in special circumstances (must still be in good faith), 2-209(2): if parties decide on a no-oral-modification (NOM) clause, UCC will enforce o Departs from CL, which says NOM clauses are ineffective because parties are always free to modify however they want 2-209(3): Statute of Frauds must be satisfied if modified contract is within SoF. o CL NOM clause unenforceable (freedom of contract), UCC is enforceable. Most courts have held that not only is a writing required when the modification brings the K within the statute, but also that all mods must be in writing when K was originally within the statute o Commentators disagree, say an oral mod of written agreement would be enforceable unless the modification would either change the quantity term or increase the price above the $500 UCC threshold 2-209(4): an oral modification made under a NOM clause will be effective as a waiver of NOM clause when one party relies on the oral modification. o Alternative view uses traditional meaning of a waiver (surrender of a known right- it’s a subtraction from K, as opposed to a modification, which is an addition to K) of NOM clause, so most traditional waivers are effective in the face of a NOM clause o Reverses 2-209(2) for some situations Alaska Packers’ Association v. Domenico (1902) Facts: D contracted with a group of sailors to perform regular duties. Sailors stopped working and demanded more $. D signed new contract agreeing to higher pay. Upon returning, D paid only the original contract price. Rule: Pre-existing duty rule: Where parties enter a new agreement under which one party agrees to do no more than he was already obligated to do, the new agreement is unenforceable for lack of consideration. A party cannot benefit from his or her own bad faith by refusing to perform a contract in order to coerce another party relying on that performance into a new agreement for more beneficial terms. Notes: Should we enforce all consensual modifications? What about union strikes against current contract terms? Courts generally want modifications to be supported by new consideration (even a peppercorn). Exceptions which allow one-sided modifications (above). Johnson: Classic elucidation of the “hold-up” game. Like duress. To remedy, simply add some addition to performance: “and we’ll swab the deck”. Kelsey-Hayes Co. v. Galtaco Redlaw Castings Corp. (1990) Facts: D entered requirements contract to sell castings to P for use in brake assemblies. Due to monetary losses, D asked for price increase or would halt production. P unable to find an alternative supplier and feared injured business reputation and monetary damages. Agreed to terms, but refused to pay. Rule: Subsequent contract will not operate as a waiver if it was entered into under duress. A contract is voidable under the doctrine of duress “if a party’s manifestation of assent is induced by improper threat by another party that leaves the victim no reasonable alternative.” The doctrine does not require an illegal threat, but merely a wrongful threat. Buyer must at least show there was some protest against the higher price. UCC 2-209: Obligation of Good Faith Price increase modification unenforceable if procured by bad faith (coercion). Can still make duress argument even if modification done in good faith. Roth-Man Test: Good faith a limitation on modification under UCC, Article 2. Two-part test: 1. A party may seek good faith modification when economic exigencies exist prompting an ordinary merchant to seek a modification to avoid a loss on the contract. 2. Even where circumstances do justify asking for a modification, it is nevertheless bad faith conduct to try to coerce one, by threatening a breach. Brookside Farms v. Mama Rizzo’s Inc. (1995) Facts: P and D entered into a requirements contract whereby P promised to supply fresh basil. After entering into the contract, D requested P remove stems from the basil leaves. D agreed and P promised to pay more. D accepted orders and issued payment, but bank refused to honor the check due to insufficient funds. 41 Rule: Oral modifications of a contract that fall under SoF are enforceable (NOM clause of UCC §2-209). SoF requires that any contract for the sale of goods for the price of $500 or more must be evidenced by some writing sufficient to indicate the contract between the parties and must be signed by the party against whom enforcement is sought. Any oral agreement that materially modifies a contract under the Statute of Frauds is unenforceable. The doctrine of promissory estoppel may be invoked when one party reasonably relies on the oral promise of another to reduce the oral modification to writing. This writing need not be supplied to the other party to be enforceable. Regarding estoppel, MRI’s promise to note the original modification for the purpose of bringing it within the controlling language of the contract was reasonably relied upon by Brookside. It is immaterial that the notation was never delivered to Brookside. It is bad faith for MRI to now complain about a course of action that it willingly engaged in. No-waiver clause is equivalent to a private SoF, subject to the same exceptions, such as part performance. Notes: NOM (no oral modification) clause can usually be waived. Can be overcome by actual performance. Modification through settlement: offering to pay less to settle a debt now (discharge agreement). XXI. EXPRESS CONDITIONS Express condition: distinct term in a contract where duty of one party depends on the occurrence of an event (“squawk like a chicken”). Must emphasize that failure of satisfying condition will void the contract. An express condition must be stated in unambiguous language. Will not be found if there is another reasonable interpretation. Express conditions require strict compliance, but a promise only requires substantial performance. o Bias in favor of a promise rather than express condition. o Synonym for promise: constructive condition. Prevention of condition: condition excused if promisor wrongfully hinders/prevent other party from satisfying the condition (2nd Restatement §254). Johnson’s Performance Curve (0 100% Performance) o At what point would the court definitively say one party’s underperformance justifies the other party pulling out of the deal? Substantial performance Material breach Excuses for EC: forfeiture, impracticability, impossibility, etc. Attempt to use creepy cases too. Waiver and Estoppel of an Express Condition Obligor can waive the right to insist on fulfillment of the condition (waiver is effective without consideration or reliance if condition was not material (only minor)). If material condition, could still be overcome by an estoppel based on obligor’s expression of intention not to insist on it, followed by obligee’s prejudicial reliance. 2nd Restatement §224: a condition is an event, not certain to occur, which must occur before performance under a contract becomes due. Substantial performance will not suffice. enXco Development Corp. v. Northern States Power Co. (2014) Facts: Express condition in construction contract that P had to obtain certification by certain date. Failed to do so due to temporary delays, despite having 29 months to do so. Rule: A party to a contract may not use the defense of impracticability to excuse the performance of a condition precedent if the party’s own inaction caused the non-performance. P should have appreciated the risk it assumed by agreeing to obtain the certification by a certain date and was aware that D could terminate the contract if ailed. Delays foreseeable. 42 Notes: Express conditions not found if there is another reasonable interpretation (promise). Judges really only enforce serious, material conditions. “Squawk like a chicken” term not material – could be eliminated by the court. Waiver (minor conditions) vs. estoppel (major conditions). Johnson: Forfeiture argument can fail if we aren’t sympathetic to the party. If it was a fair fight, too bad. 2nd Restatement §229: Forfeiture refers to the denial of compensation that results when a party loses his right to a business arrangement after substantially relying on expected performance. (Only really applies in a court of equity.) JNA Realty Corp. v. Cross Bay Chelsea, Inc. (1977) Facts: D leased commercial property to restaurant for 10-year term, with option to renew. Lease required restaurant to inform D at least 6 months prior to the end of the lease term to exercise option. D informed P two weeks before the end of the lease that the option had expired and P would need to vacate the premises. P shortly after provided notice of its intention to exercise the option, but D refused to honor the option. Rule: When a tenant is likely to suffer forfeiture for negligently failing to exercise an option in the specified time period, that tenant is entitled to equitable relief if it would not prejudice the landlord. P only acted negligently here. P also made valuable improvements. Dissent: A tenant should not be awarded equitable relief when it has been careless with its obligations under the lease. The lease, as written, should be enforced. Equitable relief should be limited to fraud, mistake, an accident, or other excusable occurrence. Allowing a tenant equitable relief under the facts of this case permits tenants to take advantage of market fluctuation. Notes: At law, time is of the essence in lease renewal options: vital condition. But at equity, court is more concerned with unjust enrichment. Trend is towards equitable relief. Johnson: Should client notify? Implied obligation of good faith and fair dealing? 2-tenant risk. Damages for improvements. Specific performance; time and energy expenditure of finding new tenant wasted. Maybe tenant won’t be kind/respectful (vindictive). When do you have optimal leverage? After breach. Maybe during tenant’s busy season. For options to purchase real estate, courts uniformly deny equitable relief for failure to renew. Constructive Condition (Promise): doesn’t really exist, just a way of saying that exchanged promises depend on each other. Judicially-created to determine consequences of breach when not spelled out in an agreement. 3 categories of conditions: o express o implied-in-fact (from conduct of the parties) o constructive (created by court for reasons of justice) Requires substantial performance. o Courts sometimes turn ECs into CCs to get around them so that substantial performance is enough. o Minor or immaterial deviations from the contractual provisions do not amount to failure of a constructive condition. o What % do we want to see? o Substantially performed or materially breached? If breach uncured, other party excused. o Factors constituting substantial performance: Whether performance meets essential purpose of the contract (main concern). Extent of the contracted-for benefits received. If damages will be adequate compensation. If a forfeiture will occur. If breach was wrongful, willful, or in bad faith. o Most courts will hold substantial performance for parties who have rendered more than 90% performance. Jacob & Youngs, Inc. v. Kent (1921) Facts: Contractor used pipe from wrong manufacturer, homeowner wants them to redo; he won’t because it’ll require ripping apart the house; homeowner withholds last payment. Rule (Cardozo): If a party substantially performs its obligations under a contract, that party will not be forced to bear the replacement cost needed to fully comply with the agreement but instead will owe the difference in value between full performance and the performance received. Court transforms EC (pipe brand) into CC because of 43 forfeiture: contractor rendered substantial performance. “Substantial performance” is a question of degree and is appropriate for determination by a trier of fact. Defect in the pipes supplied is insignificant in relation to the overall project. Even though full performance of the contract was not completed, principles of fairness and equity justify not penalizing SC. Dissent (McLaughlin): Because Kent contracted for Reading pipe, that is what he should have received. Notes: Breaching party who provides benefit to injured party has non-contract remedy: restitution argument to prevent unjust enrichment. Divisibility: way of compartmentalizing a transaction. Divide contract into parts and see which satisfied (10/25 houses built. Collect on those 10. See 10 as completed & paid. 15 as excused. May not be viable if partial completion harms value of the rest. Restitution vs. forfeiture. Result of breach is forfeiture. If that forfeiture leads to unjust enrichment, then restitution. No free 80% house completion. Remedy for substantial performance: difference between promise made and actual performance. Remedy for material breach: excused from performance. Can walk away. Distinction up to fact-finder. XXII. MATERIAL BREACH Is the breach material? Consider below factors. If so, suspension of performance of other party justified until breach is cured. 2nd Restatement §241: In determining whether a failure to render or to offer performance is material, considerer: Extent to which breaching party has already performed. Whether breach was willful, negligent, or the result of purely innocent behavior. Extent of uncertainty that breaching party will perform remainder of contract. Extent to which, despite the breach, the nonbreaching party will obtain the substantial benefit bargained for. Extent to which the nonbreaching party can be adequately compensated through damages. Degree of hardship that would be imposed on breaching party if breach were held to be material. Total Breach Material becomes total if uncured. Sufficiently serious to justify discharging obligations to perform. To determine totality, consider above factors, plus: o Extent to which further delay appears likely to prevent or hinder making substitute arrangements by nonbreaching party. o Degree of importance the terms of the agreement attach to performance without delay/ Effects of partial breach: o Immediate cause of action for damages caused by breach. o Suspends, but does not excuse other party’s duty of performance. Effects of total breach: o Immediate cause of action for breach of entire contract. o Excuses further performance by innocent party. Sackett v. Spindler (1967) Facts: D sold P shares in company. P delayed in paying multiple times after numerous opportunities to cure. Rule: If a party commits a total breach of the contract, then the other party is discharged from further performance. However, if a party commits only a partial breach of the contract, then the other party’s action in suspending further performance constitutes unlawful repudiation, which in turn constitutes a total breach of the 44 contract. Whether a breach is total or partial depends upon the materiality of the breach (consider above factors). Here, D justified in terminating contract because it was extremely uncertain that P would comply. Johnson: Innovation of some jurisdictions: material breach does NOT give injured party right to walk away. We need total breach which means material breach is uncured. Tables turn when repudiate other’s performance as inadequate. Made in the realm of substantial performance. XXIII. REMEDIES FOR BREACH (DAMAGES) Expectancy measure of damages: net value P expected from due performance (difference between contract price and market price). Restitution measure of damages: benefit you conferred upon breaching party. o Unjust enrichment – restitution – equitable recovery (leftover construction materials & plans). Reliance measure of damages: sunk expenses. Return of money put in before contract breached. Specific Performance: ordering D to cooperate with P to exchange performance as originally agreed. o Equitable remedy, not remedy at law. o Extraordinarily rare. 45