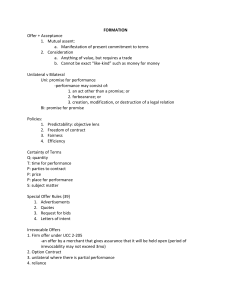

Contract, see §17(1), is a bargain with: o Generally A promise that the law enforces Vital to support the functioning of a market-based economy Background Covenant Enforce promises made under seal Only enforce when sufficient evidence that promise was made and promisor intended to be legally bound to promise Debt When wanting to recover sum of money Required quid pro quo; if the promisor got some sort of benefit of the promise Assumpsit Also where tort law comes from Liable to person for harm caused by breach of duty Misfeasance (initially), then extended to cases of nonfeasance Detriment to promisee, eventually came to recognize making a promise as a form of detriment Unilateral vs. bilateral Bilateral contract Acceptance by promise only OR acceptance by promise or performance Unilateral contract Acceptance by performance ONLY (NOT promise) Relationship between parties in unilateral/bilateral contracts can be analyzed in terms of "right" and "duty" A has a right to initiate legal proceedings against B for failure to do an act, and B has a duty to do that act In strict sense, there can never be a duty without a right and vice-versa Unilateral there is a duty on one side and right on the other Bilateral there is a duty and right on both sides o Manifestation of mutual assent, see §22(1): Manifestation Secret intentions that are not expressed are irrelevant w/r/t manifestation requirement Only outward expressions are considered Common to treat formation of K as two distinct steps (offer and acceptance) but the reality is that it can be muddled UCC "an agreement sufficient to make a contract for sale may be found even though the moment of its making is undetermined" Elements Offer (see §24) Offer is a promise (express or implied) Elements: Offeror manifests willingness for bargain (outward manifestation of intention) Offeree subjectively understands he has the last word Offeree's subjective belief is objectively justified NOT an offer: Invitations to deal Acts of preliminary negotiation, see §26 A manifestation of willingness to enter into a bargain is not an offer if the person to whom it is addressed knows or has reason to know that the person making it does not intend to conclude a bargain until he has made a further manifestation of assent i.e. no offer if recipient knows or has reason to know sender wants last word Acts evidently done in jest or without intent to create legal relations Price quote Typically not an offer because quantity is omitted (except in real estate cases in which quantity is usually not an issue) Advertisements are typically analogous to price quotes Offer vs. negotiation Technique in which you take purported offer language and change it such that it is clearly an offer and then clearly not an offer - which is it closer to? E.g. "lowest price is 900 pounds" Clear offer: "I will set to you for 900" Clear negotiation: "lowest price entertaining offers of 900" Since language can sometimes be construed either way, it's helpful to look at the surrounding circumstances If it's a close call, typically construe as not an offer (rule of thumb) Offeror is sticking their neck out by allowing the offeree to bind them into a K merely by accepting Avoid holding someone to a binding K and subjecting them to liability for damages unless there is a pretty good indication that they wanted to enter into a contract Want pretty unambiguous indication that there was an offer Advertisements Generally construed as not an offer but instead an invitation to deal First come, first served When specified in conjunction with a quantity, the seller has already had the last word: "the first person to take me up on the offer gets it" Similar language: "subject to prior sale" Such language is required for the ad to be construed as an offer Consumer protection Statutes that protect consumers against unfair/deceptive marketing practices Some states may have statutes which imply "first come, first served" term of advertisements, i.e. the seller must sell at the advertised price unless the buyer knew or had reason to know the price was a mistake But see Carbolic Ad's offer was limited to buyers (limiting language) Typical quantity sensitivity is not applicable Offering money, not a product The law assumes the offeror can get the money to pay (as opposed to being able to supply an indeterminate number of products) Besides, the ad noted they have the money Auctions Auctioneer not bound to accept an offer from a bidder unless described as "without reserve" Bidders are making offers which can be retracted/revoked until accepted by auctioneer (e.g. by hammer/gavel) Public bidding on construction Ks Similar to auctions but in reverse Sellers rather than buyers are making the offers Once offer is accepted, K is binding Unless recipient knew or had reason to know that there was a mistake Derives from §24, objective definition of assent Personality of offer No other person can interpose and adopt the K Formal contract contemplated Writing customary? Complex transaction? Agreement on all terms? Performance or substantial preparation for performance? Esp by promisor Big money? Terms Express Implied Implied in fact Based on the facts of the agreement Implied in law Based on legal rules AKA "constructive terms" or "default rules" If the parties don't express a position about a particular term, it may be filled by a default rule (if applicable) Constructive conditions of exchange (special class with bilateral Ks) If promises can be performed simultaneously, each promise is conditioned on performance of the other party's performance Promise is satisfied by tender of performance If simultaneous performance is not possible, and not agreed upon by the parties, the 2nd performance is conditioned on the 1st performance If not specified, the longer of the performances must go first E.g. mow yard in exchange for $50 "in exchange for promise to pay $50" - longer of the 2 is mowing the yard, so the mowing should come first "will pay $50 in advance" payment first is explicitly specified E.g. at-will employment has a constructive term of reasonable length of employment (unless otherwise agreed upon) Termination of Offer / termination of power of acceptance The power of acceptance is conferred by the offeree Lapse, see §41 Specified time in offer OR reasonable amount of time Depends on the circumstances E.g. typically an offer made by one to another in a face-to-face conversation is deemed to continue only to the close of their conversation and cannot be accepted thereafter E.g. things traded on open markets with wild price fluctuation - reasonable amount of time is short Offeree knows or has reason to know offer no longer in effect Subject matter of offer can give clues Means of transmission Whether there is or isn't urgency E.g. face-to-face convo or phone call, see above Late acceptance is a counter-offer Revocation Common law rule is that an offer is freely revocable until accepted In some civil law jurisdictions, offers are irrevocable for a reasonable amount of time unless otherwise specified Concerns Protecting the offeree and their reliance on the offer Protecting the offeror that the deal is freely revocable Give the offeree a reliable basis on which to continue the decision-making process Types Direct Communication, see §42 Offer terminated/revoked when offeree receives manifestation of offeror's intention not to enter into the proposed contract Indirect Communication, see §43 Offer is revoked if offeree acquires reliable information that offeror has taken definite action with an intention to enter into the proposed contract (with another party?) General Offer, see §46 An offer to the general public (e.g. advertisement) must be done in an equal (or similar) manner and does not require it be communicated directly to the potential offerees E.g. offer in an ad may be revoked by a notice in a similar ad in the same publication Other Rejection by offeree Exceptions Offeror has manifested a contrary intention (in the offer itself or otherwise) that the offer will stay open despite a rejection Offeree indicates otherwise (an intent to take it under further advisement) Option Ks (see below) Counter-offer has the same effect as a rejection Death or incapacity of offeror Relic of subjective theory of Ks (which has mostly been rejected) But death still serves to terminate an offer except in the case of option Ks Option Ks A fixed period specified directly or indirectly during which the offer stays open, i.e. the time during which the offeree must exercise or "pick up" the option Offeree may be called optionee Offer remains open for the period even if Rejected by the offeree Death (or incapacity?) of offeror Acceptance under option K not operative until received by offeror (exception to mailbox rule, see below in acceptance) How created Promise to hold the offer open which is supported by consideration This is a distinct promise from the underlying K connected to the offer which is to be left open Binding as an option K, see §87(1)(a) In writing and signed by offeror Recites purported consideration Proposes fair exchange within a reasonable amount of time A "firm offer" under UCC 2-205 Offer by merchant (any business person, see 2104(a), not consumers) In writing signed by offeror, within firm offer clause separately signed Irrevocable for the time stated If not stated, for a reasonable time Time never to exceed 3 months Unilateral K, commencement of invited performance, see §45 An offer seeking performance rather than a return promise which generates the beginning of the sought performance by the offeree Within the specified time limit or otherwise a reasonable amount of time Only unambiguous commencement of the bargained-for performance counts Preparation for performance is insufficient Was idealistic in R1 but was so persuasive that effectively became a restatement in R2 The option K is separate from the underlying K but makes that underlying K irrevocable! Reliance by the offeree AND Acceptance, see §50(1) Manifestation of assent in manner invited or required by offer Offeree manifests assent by promise or performance, see §18 Outward expressions determine whether promise has been made Actual intentions are only relevant to the extent in which they've been outwardly manifested, i.e. words/conduct Acceptance must comply with terms of offer, see §58 If offeror invites acceptance by promise OR performance, see §62 (1) beginning performance = acceptance (2) beginning performance = implied promise Necessarily a bilateral K If offeror invites acceptance ONLY by promise beginning performance is not acceptance because it is not what the offeror bargained for Necessarily a bilateral K If offeror invites acceptance ONLY by performance Tendering performance is the only manner to accept Necessarily a unilateral K Unless offer manifests a contrary intention, an offeree who learns of offer after rendering part of requested performance may accept by completing the requested performance, see §51 presumes all offeror is really bargaining for is completed performance, unless offer specifies otherwise Prescribed vs. suggested means of acceptance, see §60 Issue of interpretation whether the offer suggests or prescribes Unless "language or circumstances" indicate otherwise, offeree can accept in any reasonable manner, see §30(2) In cases of doubt, offer invites acceptance by promise OR performance, see §32 Rare that offeror only wants performance But sometimes a promise is difficult or worthless, e.g. offer of reward of $100 for return of lost pet snake Promise can be made by words or inferred wholly/partly by conduct, see §4 When actions are ambiguous, assume not acceptance (as a rule of thumb) E.g. office remodeling case: builder argued purchasing lumber for the job was acceptance, but he routinely purchases lumber so no way to know it was for the particular job Notice Acceptance by performance ONLY (unilateral contract), see §54 No notice of acceptance required, unless offer requests it (or unless offeror would not know or have reason to know that performance was completed?) Acceptance by promise (bilateral contract), see §56 Unless offer indicates otherwise: Offeree must notify offeror of acceptance with reasonable diligence OR Offeror must receive notice within reasonable time If no proper notice, offeror is discharged of contractual obligation When silent on the issue, notice is required Mailbox rule, see §63(a) Acceptance effective when it's put out of the offeree's possession Exceptions o The offer provides otherwise, i.e. the offeror can alter the mailbox rule Acceptance under option K not operative until received by offeror If communication is ambiguous, tend to say that it is not sufficient acceptance / notification of acceptance Acceptance and notice of acceptance are two different things Once accepted, the K is formed There may be an additional requirement of notice, and failing to do so will discharge the offeror's contractual obligations Court discussions often assume acceptance and notice of acceptance are one and the same, even though they are technically distinct Notice is only an issue when the offeror wants to back out Counter-offer Purported acceptance which adds qualifications (additional or different terms) is not acceptance but a counter-offer, see §59 Counter-offer: offeree proposes different bargain with respect to some subject matter, see §39(1) Mirror image rule Acceptance can't change the terms of the offer, therefore this would be a counter-offer But an inquiry about the possibility of changing the offer might not be considered a counter-offer (see p. 200) Silence is not acceptance, even if the offer says so, see §69 Exceptions Acceptance by implied promise Because of previous dealings or otherwise, it is reasonable that the offeree should notify the offeror if he does not intend to accept, see §69(1)(c) Accept offered services with reason to know offeror expects compensation and with reasonable opportunity to reject, see §69(1)(a) Acceptance of property §69(2) State and federal statutes limit this for unsolicited consumer merchandise E.g. book of the month club (unsolicited) But in commercial context, CL rule applies If the offer invites silence or inaction as acceptance, and offeree intends to accept by silence or inaction, No notice of acceptance necessary, see §56 AND Consideration Generally Not about the benefit to the promisor or detriment to the promisee Whether something is a benefit or detriment depends on perspective R2 does away with the concept of benefit/detriment w/r/t consideration, see §79(a) Benefit/detriment language sometimes pops up in opinions "legal benefit" or "legal detriment" essentially means it wasn't that but was sufficient to satisfy the consideration requirement Concept can be rigid, inflexible, and sometimes produce harsh results Overinclusive to some degree Capturing promises that should not be legally binding But these can be dealt with with K defenses Bigger problem is when underinclusive Existence of promise and intention is clear Instinctive reaction is promise should be enforced in one way or another Can take the form of, see §71(1): Performance (unilateral) Types Positive act (other than a promise) Forbearance (not doing something) The creation/modification/destruction of a legal relation Essentially anything the promisee does or refrains from doing can be consideration Presume that all promisor really cares about is the completed performance, see §51 i.e. partial performance prior to learning of offer will still allow for effective consideration on completion of performance E.g. bounty hunter who captures escaped convict then learns of reward offered for the capture AND return of the convict; promisor is really bargaining for the return of the convict Only one enforceable promise: only the promisor can be bound to a contractual obligation (but enforceable nonetheless) Much less common / economically significant than bilateral Ks Return promise (bilateral), see §71(2) Exchange of promise for a return promise Both promises are enforceable contractual promises Both promisors are bound to perform Encourages reliance on promises Facilitates complex business But do not need to show reliance-in-fact, why? Line-drawing problem: how much reliance is enough? Proof problem: how can it be proven there was actual reliance? Uncertainty: whether promise will be enforceable or not (as the promisor, you'd have to guess whether the promisee has/will rely on your promise) Reliance-in-fact rule would discourage actual reliance Not completely intuitive If it's not clear whether agreement if for performance or promise of performance, assume promisor will take either, see §32 Promise is preferred over performance only, so we presume promisor was bargaining for a promise Language and circumstances are used to determine whether the offer requires performance or promise, see §30(2) See also acceptance From the perspective of the parties: Promisor Consideration is the thing sought by the promisor in exchange for the promise, see §71(2) i.e. promisor makes the promise to get the thing The thing (which will serve as consideration) need only be ONE of the reasons to make the promise, see §81 The law generally does not second guess the promisor's reason for the making the promise Even if the promisor was bluffing or lying, he was using the promise to get the thing he wanted from the promisee Conditional promise is the first thing to look for when looking for consideration i.e. if you do this, I promise to do that Conditions placed on the promise A promise is conditional if its performance will become due only if a particular event occurs (the condition) Does not mean the promise is not binding, just that the event must happen before promisor must perform Court may impose conditions by implication, AKA "constructive condition of exchange" E.g. Lake Land, continued employment have to be for a reasonable period of time to serve as consideration E.g. for signing a noncompete agreement E.g. no consideration if employee asked to sign noncompete on last day Express terms trump implied terms But see conditional gift promise, infra Promisee Consideration is the thing given by the promisee in exchange for the promise, see §71(2) Only consideration if the promisee does it to get what's promised Something must be given by the promisee in exchange for the promise, see §81(2) The promise only has to be ONE of the reasons for doing the thing the promise aims to induce As long as the promisee does whatever the promisor wants w/r/t the promise, the law generally won't second guess the motive for doing so Third party, see §71(4) Consideration can be given by/to a 3rd party, so long as it is bargained-for Doesn’t matter who fulfills which piece of considerations as long as there is a BFE Still consideration even if… Mixed motives Motivation that satisfies consideration need not be the only, the primary, or even a significant motivation for engaging in the promise But making the promise does have to be one of the motivations Not a very hard standard to meet Courts only inquire into motive and purpose when they have to, because it's hard to figure out Imbalance of values exchanged No equivalence requirement, see §79(b) The focus is merely whether there was a BFE Doctrine not suited to evaluate the relation between the values of the exchanged things Law does doesn't entirely disregard unfair exchanges, but manifests in other doctrines NOT consideration Gratuitous promise A promise lacking consideration Not legally enforceable But a gift is irrevocable if and only if fully performed Property law requires delivery of the gift (the wretch of delivery) Evidentiary function Donor actually intended to make the gift irretrievably Cautionary function Should signal to donor that he is doing something significant, which probably cannot be undone The consideration requirement for a promise to be enforceable serves similar purpose to delivery requirement of gifts Evidentiary When made in the context of a BFE, there is more reason to believe promisor made the promise and intended to be bound by it Promisor wanted and got something in exchange for making the promise Cautionary Should signal to promisor that they are making more than a bare promise Why not enforce gratuitous promises? Administrative costs Who to believe? More lawsuits If any promise no matter how casually made could be enforced in a court of law, people would be overly cautious about making promises Would be detrimental to potential promisees We like to depend on promises even if not legally enforceable Is a legal apparatus necessary to hold ppl accountable to their gratuitous promises? Morality / social norms and pressures may be sufficient Especially outside of the market, there is less need for legal enforcement Some (all?) states allow binding gratuitous promises in writing by statute Trusts Wills Deed of future interest Must be in writing, lot's of formality to satisfy cautionary/evidentiary concerns Pretextual/nominal/sham consideration AKA a peppercorn The thing presented as consideration is merely there to satisfy the requirement, not something actually desired and inducing the promise If there is an extreme difference in value of the things exchanged, it could be an indicator that there is no BFE, but it is not the actual test for BFE R1 said a sham bargain is good enough, so long as the parties went through the motions of pretending it was a bargain But this is outdated and modern approach requires BFE If it were allowed, we might capture promises that one of the other party did not actually intend to be legally bound by Evidentiary/cautionary factor Arguably satisfied with a peppercorn b/c it is a charade specifically to satisfy this requirement, thus producing evidence and signaling caution to the parties Past consideration is no consideration Conditional gift promise There is a condition but it wasn't to induce the thing, it was just incidental to the thing E.g. retirement payments are conditioned upon the person being retired, but doesn't necessarily mean the payments were promised to induce retirement E.g. insurance: payout is conditioned on an accident, but the insurer is not inducing you to get into an accident; that is not what they are bargaining for Illusory promise For a K to bind both parties, when based on an exchange of promises, both must have assumed some legal obligations If one of the parties is free to back out at will, the promise is illusory and provides no consideration In other words, the promise is lacking mutuality of obligation Illusory promises are a sham, like peppercorns Perpetrated by the promisee, whereas peppercorn is perpetrated by promisor Easier to look at the definition of promise in §2(1) instead of the alternative analysis found in §77(a) for determining whether promise is legitimate or illusory Only illusory if so lacking in substance that no promise was made at all Satisfaction clause Could be construed as creating an illusory promise because the party has wide latitude to back out of the obligation Concerned that "satisfaction" is subjective and the party could say they are not satisfied even though they might be Condition could be used as a pretense for backing out of a deal for no legitimate reason Approaches for controlling the discretion of the promisor: Objective standard (objective satisfaction) Satisfactory according to recognized objective criteria E.g. where satisfaction pertains to commercial viability or the like If the subject matter lends itself to objective standard of satisfactory quality, it will be presumed unless otherwise made clear Lack of satisfaction cannot be founded capriciously However, when there are many factors, applying a reasonable person standard would be difficult Subjective standard (subjective satisfaction) Satisfaction is one of judgment made in good faith based on fancy, taste, or judgment Or anything else that doesn't lend itself to objective standards of what is good/bad, acceptable/unacceptable How to judge? Dissatisfaction is genuine When not satisfied in good faith, honestly Honestly and truly dissatisfied Objective standard of satisfaction can only be used when there are uniformly accepted, objective standards to use as a basis E.g. agreement to transfer real estate, if buyer gets enough satisfactory leases Whether a lease is good or bad is not subject to a defined objective standard; there are a lot of factors to consider E.g. how the store fits into the overall mix of offerings, business savvy of tenant, credit rating of tenant, etc. Examples "I promise to forbear until I don't want to forbear anymore" Not a promise at all; illusory Promising to continue employing as an at-will employee is no promise at all Implied promises/constructive terms of law Implied promises in all exclusive agency agreements Acceptance of exclusive agency is an assumption of its duties Codified in UCC 2-306 Good faith effort to make sales under the agreement Good faith meaning Objective standard for merchants (observance of reasonable commercial standards of fair dealings) Subjective standard for non-merchants (honesty) E.g. fashion designer case in which P would have exclusive right to mass market D's brand and designs, parties would split profits from all sales; without an implied promise that P would make reasonable efforts to sell wares, D would receive no benefit from the K Real estate purchase contract where buyer must secure financing Implied promise on the buyer's part to use reasonable efforts to secure financing Buyer would be in breach of the sales agreement if he did not use reasonable efforts Moral obligation A promise made in recognition of a moral obligation arising from a previously received benefit is generally not enforceable Exceptions: Contractual obligations that would otherwise be barred by SOL Debt discharged in bankruptcy Voidable contract obligation If promisor reaffirms the obligation with a new promise The new promise removes the rationale for not enforcing the old promise The promise essentially recognizes an unenforceable obligation to essentially reaffirm it Or it does away with the legal technicality which prevents enforcement, because just doesn't make sense anymore A subsequent promise weakens the need for protections when a benefit has been thrust upon a party without their consent They are essentially saying, "I don't want to be protected, I want to be bound" "Promissory restitution" (as described by Bru), see §86(1) This does not satisfy consideration, but it is a basis for enforcement Requirements: (a) promise (b) promisor must have previously received a benefit from the promisee (c) promise must have been made in recognition of that previous benefit (d) promise should be enforced to the extent necessary to prevent injustice Factors to satisfy evidentiary concern Promise was made in recognition of a benefit Extent of benefit (to promisor): the bigger and more concrete the benefit is, the more likely the promisor intended to make and be bound to the promise Extent of effort of promisee (or extent of detriment): the bigger, the more likely the promisor intended to make the promise in exchange for what the promisee did Substantial part performance Written promise Factors to satisfy cautionary concern Written promise Exception, see §86(2) A promise that otherwise satisfies §86(1) is not binding if: (a) the benefit conferred was a gift or promisor was otherwise not unjustly enriched Burden on D to show OR (b) the value of the promise is greatly disproportionate to the benefit received Not necessarily mathematically precise, because we might want to enforce the promise so as not to have to calculate the value of the benefit conferred o o o o Don't want to enforce restitution for more than the value of the benefit conferred This reverses all of the presumptions for ordinary restitution Makes it a lot easier for a promisee to recover in restitution when there is a subsequent promise Reverses the presumption that the benefit was conferred gratuitously As a restitution obligation, it cannot be used to recover restitution for a gift, even if the benefited party makes a subsequent promise NOT a majority approach! Distinct minority But this section recognizes the tendency for courts to want to enforce promises in these situations and provides a framework to do so There is a moral obligation to perform every promise If morality was the guide (or sufficient alone for consideration), every promise would be enforced AND Definiteness, §33(1) Even if otherwise an offer, cannot be accepted unless the terms are reasonably certain Terms are reasonably certain if they provide a basis for: Determining if there was a breach AND Giving an appropriate remedy Promises within a K can be enforced notwithstanding other promises within the same K that cannot be enforced for lack of definiteness Even if a K empowers one or more parties to make a selection of terms in the course of performance, it may still be sufficiently definite, see §34(1) E.g. range of quantity is OK AND Assent Intent to be bound Agreements to agree? What was intent wrt not being able to agree, e.g. on price, down the line? Gap-filler or no contract? What did the P know or have reason to know about the other party's intent to be bound? Precontractual liability o General rule of no liability until offer and acceptance o If an offer invites an offeree to accept by rendering a performance and does not invite a promissory acceptance, an option K is created when the offeree begins the invited performance, see §45 One cannot tender a performance that is to extend over a period of time (e.g. crossing the Brooklyn Bridge) Problem addressed by §45 can be avoided if the offer seeks a promise as acceptance and a promise is given or inferred Preparation for performance (but not unambiguous commencement of the actual invited performance) does not (yet) create the option K and thus no liability o Claimants seeking recovery for services performed during negotiations have rarely succeeded Restitution may be available, see §63 But a down payment for land in a failed negotiation should be returned Battle of the forms o Sequence Buyer's request for a quote Seller's quote o o o Buyer's purchase order (the offer) Seller's order agreement (change of terms, therefore it's a counter-offer) Seller ships Buyer takes delivery and pays (acceptance) Issues with CL mirror image rule A scoundrel could seize on a difference in fine print between purchase order and sales agreement (merely a technicality) on account of the mirror image rule to avoid obligation Not whether there was a contract, but what were the actual terms? The forms differ which causes a dispute as to what the terms are What's the answer under CL? Under the above sequence, seller's terms prevail as they were different from the purchase order and thus a counter-offer "last shot" rule, favors the seller This is arbitrary, because neither party really bargained over those disputed terms UCC sought to resolve this in 2-207 Only applies to the sale of goods! (like the rest of §2) Is there a K? see UCC 2-207(1) If there is a K, what are the terms? UCC Supplements CL rules Supplants in some areas, or falls back to CL Only applies to the sale of goods! Between merchants = both parties are chargeable with knowledge or skill of merchants Merchant = anyone who holds themselves out to have the knowledge or skills peculiar to the business, see 2-104(1) Warranty disclaimers and indemnity provisions systematically favor sellers Arbitration agreements don't inherently favor one party over the other Neutral generally As applied, might favor one party over the other in a particular context Question of fact re: who is favored and whether it could be a material alteration Drafting glitch? 2-207(2) only applies to additional terms, not different terms? Definite expression of acceptance Serves as acceptance even though it states terms additional to or different from those offered or agreed upon Replaces the mirror image rule in many cases Even if (form acceptance) Material alteration, see (2)(b) Offer expressly limits acceptance to the terms of the offer, see (2)(a) Different term E.g. buyer purchase order includes a broad warranty whereas seller's order acknowledgement includes a warrant disclaimer Ways to handle Fall out K is based on offeror's original terms If court interprets UCC as 2-207(2) does NOT apply OR it only applies to the different term in the acceptance Gives too much of an advantage to buyer's terms Reverse advantage of CL "last shot" rule Knock out Differing terms cancel If court interprets UCC as 2-207(2) applies to BOTH different terms UCC gap fillers are applied More neutral, more consistent with philosophy of 2207 Support in official comment 6 Most courts use knock out instead of fall out K with term If affirmative assent Additional term Ways to handle K with term If assent Between merchants Both parties are chargeable with knowledge or skill of merchants See 2-104(1), (3) Alternatives K with term Unless: Offer expressly limited, see 2207(2)(a) OR Objection, see 2-207(2)(c) E.g. "I object to additional terms" OR Material alteration, see 2-207(2)(b) See comment 4 re: unreasonable surprise or hardship Most courts don't apply the unreasonable hardship standard, only unreasonable surprise Non-merchant With no affirmative assent Alternatives Contract without term Unless (no form acceptance) When: Change in basic bargained-for term (price, quantity, etc.) OR Acceptance is expressly conditional, see 2-207(1) Ways to handle (differs per court) Counter-offer Defaults to CL rules Not acceptance but instead counter-offer Most courts do not go this route because it gives too much of an advantage to seller's terms K by conduct, see 2-207(3) Approach of most courts K with agreed terms + UCC gap-fillers K with term If assent Form confirmation of prior K One party confirms E.g. oral agreement over the phone, then seller sends over order acknowledgement form with additional terms Alternatives Additional term Jump over to "additional term" under form acceptance Different term (than expressly agreed) Alternatives Fallout K with expressly agreed term K with term If assent Both parties confirm Agreed terms Different terms Material alteration Most courts only apply "unreasonable surprise" Warranties Clause that negates customary warranties would be a material alteration Clause that turns 90 day warrant into unlimited would be material Arbitration clause would be a factual question whether it's material Not clear that it systematically favors one or the other Neutral on its face Buyer Wants to include expressly limited clause Seller Wants to include acceptance expressly conditional clause Their terms govern in a court that uses counter-offer theory Defenses o Won't enforce, even when there is a BFE o Concerns (interact no matter what K defense is at issue) Status (of one of the bargaining parties) Not responsible enough to engage in the promise Behavior (of one of the bargaining parties) Improper conduct in inducing promise Substance (of bargain) Usually don't care about the substance if there is a bargain But certain bargains won't be enforced for public policy reasons, e.g. illegal Ks Defense of unconscionability has fallen out of favor o Misc In some states there is a presumption to not enforce noncompete clauses In some they are effectively or actually unenforceable Not a matter of lacking BFE, just hostile to enforce agreements such as these which restrict free trade o Status Capacity Policy implications Protect party w/o capacity from his limitations Protect legitimate expectations of other party, that who is dealing with the incapacitated person Types Minor's Ks General rule: until person reaches age of majority, any K entered into is freely voidable at the option of the minor ONLY voidable by the minor, not the other party (cannot void the K after learning the other party is a minor) Minor can enforce the agreement if they do not want to get out of it Policy implications If minors cannot enter into Ks, merchants won't want to K with them at all If merchants don't know if a K would be enforceable upfront, they won't want to enter into the K To avoid uncertainty, bright line rule: K not enforceable Avoid messy factual determination about whether person is mature enough or whether seller engaged in unscrupulous behavior on account of them being a kid Having to include an adult in the K could deter such improper conduct on part of seller Age of majority is 18 Some states have emancipation statutes that allow minors to be declared emancipated and make legally binding Ks If the K is made as a minor, upon reaching the age of majority, person can ratify/affirm the K Minor becomes bound, can no longer void the K If person doesn't disaffirm or avoid within a reasonable amount of time, same effect: K is ratified Reasonable amount of time could be very long All it takes to ratify is some manifestation to be bound by the K On avoidance: Minor has to give back whatever they got from the K Essentially undoing the K Minor only has to give back what the minor still has to give back and not liable for the value of anything he cannot give back (e.g. gone/damaged) Exceptions: If K was for necessaries, minor liable in restitution for any benefit received which cannot be returned Necessaries include: Food Shelter Clothing Anything basic for survival and proper functioning Necessity interpreted fairly broadly Evolves as society evolves E.g. car, esp. for working minors, could be considered a necessity Don't want merchants to deny minors basic necessary items for fear of avoidance of the K Seller would only have to pay anything back to the minor if the K price was higher than the FMV, i.e. if the seller had taken advantage of the minor So protects minors from unfair Ks E.g. sale of a car, minor avoids after 2 months Assuming it is construed as a necessity, minor is liable in restitution Must give back the car and pay seller the FMV of use of the car for that period, e.g. FMV of a rental of a similar car Could be liable under the tort of fraud Minors are generally liable for torts If they misrepresented that they were of legal age E.g. sale of a car: minor has to give back the car, seller has to give back to money If car is damaged, just have to give back the damaged car Don't have to pay for the damage Mental incapacity, see §15 Only considered mental incapacity if operating under mental illness or defect, see §15(1) Inherent mental disability Not carelessness or lack of sophistication: don't have to be very intelligent to have K capacity Necessary but not sufficient for avoidance: only voidable if the mental incapacity fulfills one of two tests (below) Tests to determine if mental incapacity makes K voidable Cognitive test: Unable to understand in a reasonable manner the nature and consequences of the transaction, §15(1)(a) Only looks at ability to understand Where K is made on fair terms, and other party is w/o knowledge of mental illness, the power to avoid terminates if the K has been so performed in whole/part or circumstances have so changed such that avoidance would be unjust, §15(2) Court may grant relief as justice requires Vague, open-ended, gives court a lot of flexibility Volitional test: Unable to act in a reasonable manner in relation to the transaction and the other party has reason to know of the condition, see §15(1)(b) Not the ability to understand but to control your actions in a reasonable way Only voidable if the other party had reason to know about the impairment Greater weight to the legitimate expectations of the other party On avoidance: If other party didn’t know of the impairment, they still have full right to restitution for benefits conferred that cannot be returned on avoidance More protective than with minor's Ks Full restitution on both sides Avoiding party is liable for full value of necessaries received that cannot be returned Other party would only have to pay back anything to the incapacitated party if the K was unfair in the first place, i.e. above FMV Protects mentally incapacitated from unfair Ks Intoxication, see §16 Similar to test for mental defects, but most courts don't allow the volitional test Cognitive test: so intoxicated that person was unable to understand what they were getting into Plus (unlike for mental), other party had reason to know the person was impaired Greater protection to other party Probably because courts are less sympathetic for intoxication, which is seen as self-induced Roughly similar to minor's K: undo the K, parties give back what they still have Improper behavior Bargaining pressure Pre-existing duty rule (PED), see §73 If all you do or agree to do is perform some legal duty already owed to the promisor, that is not consideration that will support enforcement of a new promise Any contract modification that changes only one party's obligations under the K, even if agreed to by both parties, is unenforceable under PED Purpose is to police against unfairly coerced modifications to existing Ks, but it's very blunt (leading to various exceptions, noted below) Problem with PED: it strikes down not only illegitimate modification induced by coercion or blackmail, it also strikes down legitimate, mutually desired modifications that are in the interest of both parties PED rule is a consideration doctrine, so it doesn't apply to a promise that has already been performed Mostly concerned with modifications to existing Ks Exceptions: escape hatches for when courts want to get around the PED (can only get out of the PED when you have a basis to argue that one of the following exceptions apply) Rescission of original agreement When there is still performance remaining on both sides of a K, the parties can agree to terminate the K This is a separate K known as a K of rescission Bilateral agreement effective to terminate the original K E.g. in the dress-designer case, there was no substantive change between a mere modification of the original K and the rescission and new K with altered terms Was not a complete rescission because the parties did not intend to be fully unbound, they intended to immediately re-enter into a new agreement (i.e. one of the parties really was not free to walk away upon the rescission, and it was not truly a rescission then) Court bought into the charade/fiction Courts will only apply when it does appear the modification was coercive As in the dress case, if the parties would only enter into the "rescission" K in conjunction with a new K, it may not even be truly a rescission K (it is instead a pretense of a rescission) Whether the court finds a valid exception has less (or none) to do with whether there was actually a rescission and whether there was Different or additional performance Which represents more than a pretense for a bargain, that will constitute consideration for a new promise Primary factor in whether the court is actually going to uphold the modification is usually not whether the different/additional performance bargained for by promisor is merely a peppercorn; instead, whether the new promise is being extracted by coercion / illegitimate bargaining pressure Note: The exceptions above are essentially legal fiction and give the courts a lot of flexibility to try to determine whether a modification of K is procured by improper coercion and do justice as they see fit However, if the parties are not sophisticated enough to engage in this sort of rescission or different/additional performance dance, there is no basis to get around the PED Disputed obligation (honest or good faith) Only applies if the original obligation is not doubtful or subject of an honest dispute Not really clear that there even was a preexisting duty If there is a dispute in good faith, the modification is essentially an agreement to settle the dispute BFE is performance of a disputed obligation Supports policy of encouraging private resolution of goodfaith disputes Courts even invoke this exception often only when not done in a coercive way Changed circumstances or promissory estoppel-esque reliance, see §89 Less technical or formalistic and more of a frontal attack on the PED itself, much more directed at what the other PED exceptions are really concerned with Much more directly addresses the question of whether the modifications were improperly coerced or not When K has performance remaining on either side (not necessarily both sides, despite what the language in R2 might suggest) Modification binding when: Fair because of changed circumstances not known at making of K OR To the extent that justice requires enforcement in view of material change of position in reliance on the new promise, §89(c) Employed when there really were no unforeseen changed circumstances but also there was no improper coercion involved in the modification, if there is reliance on the modification, i.e. continued performance Specialized application of promissory estoppel concepts in the context of K modification But-for causation test Observed in a substantial minority No PED at all This applies to a few states K for the sale of goods In every state because of UCC 2-209(1) PED is to a 3rd-party, not the promisor on the promise sought to be enforced This exception is merely an explicit reiteration of the rule itself, which already specifies the PED rule only applies when the PED is to that particular promisor Makes sense, bc opportunities to blackmail a 3rd party are much more limited Also reflects growing hostility to PED rule in general by courts Not all courts apply this exception, there is a split (notwithstanding the stance of R2) Promise has already been performed This wasn't discussed as an explicit exception, but it is inherent to the nature of the PED Because the PED merely provides an exception to otherwise valid consideration, but if the promise is already performed, consideration is not at issue Traditional PED and its 3 traditional exceptions survive in most states, i.e. majority view The 4th, from §89, is a substantial minority A few states have entirely abolished the PED Threat of breach, generally Under K law, breach is not inherently wrongful, and thus punitive damages are not awarded o You are free to breach, as long as you fully compensate for the breach o Therefore threatening to breach is not inherently improper Critical inquiry of whether a threat of breach is legitimate or illegitimate is the reason for the breach: prompted by change in circumstances (performance is harder or makes an alternative use of their time more valuable) Duress, see §175-76 More directly address the issue targeted by the PED, but requires a more specific test to distinguish between illegitimate coercion and mere honest, hard bargaining If a party's manifestation of assent is induced by an improper threat and leaves the other party with no reasonable alternative but to enter into the K, the contract voidable by victim, see §175(1) Elements (a) improper threat, see §176 Must be improper, bc nearly all bargaining involves threats Improper per se, bc so nasty and reprehensible, even if terms are otherwise fair, see §176(1) Crime or tort (including against property) Originally at CL, these were the only type recognized and only if GBH Or if the threat is in itself extortion Criminal prosecution Even if the person being threatened is guilty of the crime Civil process in bad faith A threat of civil process is legitimate if the party making the threat has a good faith belief in the validity or merits of their case Breach of duty of good faith and fair dealing under existing contract Threat to breach is not inherently improper, it's the motivating factor which determines whether such a threat is improper If the threat of breach or exercise of rights under an existing K is made for an improper/unrelated purpose of that K This category has expanded as the PED rule has contracted In some ways this category should fall under the "improper if unfair" category, as applied by the courts, so kind of straddles the two broader categories Especially in a case where the other party had no reasonable alternative, but there was a legitimate reason to demand a K modification (e.g. increase in material/labor costs) Improper if unfair contract, harder to draw the line for these categories, so only if the terms were unfair, see §176(2) Harm to victim, no independent benefit from threat (to the person making the threat) Threat is more effective because of prior unfair dealings Sort of a catch-all Otherwise a use of power for an illegitimate purpose Also a catch-all (b) no reasonable alternative (objective) / "free will" test (subjective) Recognizes the causation element of duress May have to take into account particular circumstances of that victim, e.g. age, intelligence, background, especially as compared to the threat-maker, etc. Objective test morphs a bit into subjective test Should/could they have done more to get around the threat? Some courts apply the more subjective test (free will) Only if consequences of the threat are so severe that they deprive the victim of their free will to exercise independent judgment about whether to enter into the K Difficult to apply, so modern test is the objective one (and advanced by R2) Since objective test veers into the realm of subjective, the difference in the tests in practice may not be all that much Both essentially trying to get at the same thing, but likely easier to meet the more subjective the test is If duress is established, victim can avoid the K Power of avoidance must be exercised within a reasonable time of duress removed Measured from when the circumstances producing duress are removed On avoidance: Full restitution to both parties Back in the position before the K was made True even if the K has been fully performed on both sides Duress and PED rule work in tandem w/r/t K modifications Duress can be used in cases where PED cannot, such as where a promise has been fully performed Misrepresentation (1) words or conduct which serves to misrepresent (a) affirmative misstatement OR (b) obligation to disclose Generally no obligation to disclose what you know, except in any of the cases below or in response to a direct question about the subject, i.e. caveat emptor (i) half-truths A technically true statement but lacking enough information to prevent misleading the other person to conclude something that is untrue What you don't say is just as important as what you do say (ii) affirmative concealment Preventing discovery of information (iii) correct prior statement that has become false or misleading (iv) relationship of trust or confidence Includes others beyond formal fiduciary relationships Where transaction involves a high level of trust, e.g. between family members, doctors and patients, clergy and congregation Not limited to a particular type of relationship, depends on the actual relationship between the parties (v) §161(b) modern trend, not yet majority, nondisclosure of known fact is equivalent to asserting the fact does not exist, when all of the following elements are met: Applies when a party knows about a particular fact Party knows other party mistaken about fact Party knows fact is basic assumption on which the other party is making the K Mistaken assumption which was integral to make the agreement More than material - very, very material (almost a but-for) Essential if the fact is a basic assumption, it should also fulfill the materiality requirement (below) Good faith and reasonable fair dealing require disclosure, based on: Defect (bad faith) vs. enhancement in value (not bad faith) E.g. not considered bad faith with a K to sell land in which buyer knew some information which makes the land more valuable than the seller believes it to be landowner had just as much ability to discover the enhanced value as the buyer useful for society for ppl to invest in research, so incentivizes this practice if you make your money off of information, you can't make any money by giving that information away (i.e. to the seller, in which case you would not be able to make enough money off the property which justified the research developments in the first place) less that the buyer was taking advantage of the seller's ignorance and more that the buyer was taking advantage of his own research efforts Protects buyers more than sellers Buyers against undisclosed defects, but not sellers against ignorance to qualities that make the item more value Relative ability to discover General market information vs. individualized latent defect of the particular property E.g. knowledge that the price of corn is going to drop dramatically and selling at the higher price is not a violation of good faith and fair dealing No requirement that the maker of the misrepresentation know that what they are saying is false or made with intent to deceive the other party Intent needed for tort of fraud, not for avoidance here Allows parties to allocate risk which can facilitate K making, e.g. in lieu of spending resources to discover information to be fully informed about details material to the K, you can make an uninformed statement, and if it turns out to be a misrepresentation, it simply allows the other party to avoid the K In most cases the risk won't materialize into anything, so doesn't make sense to compel parties to fully eliminate risk before making Ks Allows reactionary modifications in good faith as new information comes to light But more likely to allow the deceived party to avoid the K if there was indeed intent to deceive, even if the other elements are weak (reliance, justified, etc.) Sometimes said that you cannot get relief from a misrepresentation of law or an opinion, but that's not really true More so whether you can tell if the statement is true/false in the first place and reliance is justified (below) o However, when something is said so subjectively (e.g. "I think I can get the tax lien taken care of"), it's hard to tell whether there has even been a misrepresentation in the first place (2) misrepresentation is material, see §162(2) Likely to induce manifestation of assent/reliance In a reasonable person OR The maker knows it is likely for THIS person Basic assumption standard (above) is higher than the materiality standard (3) reliance (aka inducement), see §167 Causation If it substantially contributes to the decision to enter into the K Substantial factor causation Not as high as but-for (as in promissory estoppel) Not as low as BFE ("at least one of the reasons"), see §81 (4) reliance was justified Essentially no good reason NOT to rely on the misrepresentation Not a reasonable person standard, more subjective You're not required to make an independent investigation, even if a reasonable person would have and even if such an investigation would have been very easy You're entitled to take the maker of misrepresentations at their word Makes the K-ing process more streamlined The point is, we don't want to allow ppl to avoid Ks based on statements that, by their nature, ppl just don't rely on Depends on the statement itself and the context The party who has been misled has the option of avoiding the K Full restitution on both sides, even with part or full performance Must be within a reasonable time of learning of the misrepresentation Option to avoid is lost by ratifying the K, such as: Not acting within a reasonable amount of time Some affirmative action (e.g. after learning the truth, continuing to use property acquired under the K instead of attempting to avoid) Election of remedies: suing the other party for tort of fraud Statute of Frauds If SOF applies, it's called a "contract within the statute" Important note: It's not the writing that makes the contract, merely an additional requirement Categories Suretyship K Guaranteeing a loan is a type of suretyship promise Exceptions for certain types, e.g. if guarantor was getting paid "the promise to answer for the debt of another" K not to be performed within 1 year of its making "the one year clause" One of the most important to be aware of Measured from when K is made (when it comes into existence, i.e. offer accepted) Measured to when K will be fully performed on both sides Courts go out of their way to get around this K is within statute only if, by its express terms, performance CANNOT be completed within 1 year Terms of the K require performance of either side more than 1 yr from its making E.g. K to build a skyscraper within 3 years: not within 1yr bc, even though unlikely, it is within the realm of possibility to complete within 1 yr E.g. lifetime employment agreement: not within SOF bc employee might die or quit K for the sale of land Transfer of any sort of interest in real property (including a lease, which is a possessory interest) Many jurisdictions have a statutory exception for short-term leases (1yr or less) K for the sale of goods Now governed by the UCC, Art. 2 Has its own SOF in §2-201: applies to any K for sales of good with sales price of $500+ Contract of executor/administrator to be personally liable for administration of decedent's estate Similar to suretyship K K upon consideration of marriage Not very common anymore except in case of prenuptial agreements Some, not all jurisdictions: Agent's contracts E.g. K to hire a real estate broker K to make a will Will may not be enforceable otherwise Writing requirement Language of original SOF (still appears in most states' SOF): "promise or agreement or some memorandum or note thereof shall be in writing signed by the party to be charged or his agent" Only the party to be charged, the defendant, the party against whom the K is sought to be enforced Plaintiff, the party trying to enforce, need not to have signed Therefore a K may be enforceable against one party and not the other On the drafting end, be sure to have a written L On the litigation end, courts have been very liberal about what kind of writing will satisfy the SOF (bc they don't like it) Notes, receipts, electronic data, even a voice recording Any tangible embodiment of the terms of the K Does not matter when the writing was made, because it itself is NOT the contract Before or after K Does not have to be prepared for purposes of SOF Does not have to be delivered to the other party (or even made for the purpose of delivering) Even if you can prove that there once was writing, you can satisfy w/o producing the writing Question of fact to be resolved by fact finder Erosion of the formality of the writing requirement over time Due to judicial hostility to the SOF Courts don't really care about the cautionary aspect (in conjunction with SOF) Only concerned about evidentiary aspect: basic terms of K and that D assented Required components of the writing Identify subject matter of K Identify the parties Must contain the essential terms of unperformed promises (those sought to be enforced) Usually: price, quantity If a term has an implied/default term, it may not be essential (even price or quantity, if there is a default) Depends on the K at issue Signature of party to be charged Can be fulfilled by other means, e.g. if not signed by D but written on their personal stationery Just has to be enough to show that the party to be charged intended to authenticate and adopt that writing as their own expression Email considered signed by that person if it is their own personal email (but could litigate whether the person actually sent the email) Indication that signing party assented to the essential terms Flexibility / liberalness of the above requirements Easy to meet the writing requirement Definiteness of the terms (and other requirements for enforceability) does not have to be established by the writing, because the writing is not the K Other evidence may be introduced to flesh out the meaning of a term contained in the writing at issue, to establish sufficient definiteness to enforce E.g. even merely the parties' initials could satisfy the identification of parties Even if the writing shows only an offer, it could be sufficient to establish the terms and assent thereof, and the K could be enforced with additional evidence that there was acceptance SOF merely requires minimal corroborative written evidence of the most essential terms of the K and that the defendant assented to those terms Can use writings not signed by D to satisfy parts of the writing requirement if D signed at least one of them and there's some way to connect the unsigned to the signed writings (to show that D assented to the terms in the unsigned writings) Exceptions to the SOF (when a promise can still be enforced in spite of SOF) K is enforceable as BFE notwithstanding SOF Uses reliance to enforce the BFE Triggered by reliance in the form of performance under the K Types Full performance exception to 1yr clause A party who has fully performed under K, notwithstanding 1yr clause of SOF, can enforce Most courts would say that full performance by one party takes the K out of SOF, can get expectation damages Part performance doctrine as exception for sale of land If under oral K to purchase land If buyer relies by 1) taking possession AND 2) makes permanent improvements OR pays part of purchase price Only benefits purchaser of land and only with reliance as specified above Promissory estoppel notwithstanding SOF SOF is not a bar to promissory estoppel recovery Less widely accepted Many courts hesitant to expand promissory estoppel into that realm Back door / end run to formal limitations to BFE / SOF Theories of enforcement o Consideration/BFE This is the normal basis for enforcement for what are considered valid Ks o Reliance (hand in hand with PE) Background Enforced via assumpsit under CL (traditionally) Generally rejected in favor of BFE because it would be harder to enforce promises, thus makes it harder to rely on promises Paradox! Unfairness of consideration doctrine has not escaped attention of the courts, thus they have carved out some exceptions based on reliance Traditional exceptions to BFE Gratuitous promise to convey land Courts would enforce if promisee relied on the promise by moving onto land and making permanent improvements to land Both elements were required for gratuitous promise to be enforceable Gratuitous promise by bailee of personal property o Bailor gives to bailee temporary possession of property for some specified purpose Required actual possession of property at issue which promise is made in conjunction with If bailee did not take possession, no liability for promise Charitable pledge Might be able to find consideration in these promises (in which case reliance exception is unnecessary?) In many cases, the charitable gift is to induce something E.g. naming a building Courts may enforce when such promises became relied upon by the charity in some way Family promises BFEs in family context are sort of a rarity Even when promisor wants to induce an action, bargaining with a family member can be awkward Even when the promisor wants to induce the promisee to do something, will rarely couch with a proper bargain See e.g. Ricketts v. Scothorn Promissory Estoppel Background w/r/t equitable estoppel Has to do with representations of fact Doctrine of EE prevents person from changing representation of fact when other person has relied upon the fact as he believed it to be Estoppel based on a promise works essentially the same way Person relies upon a promise, which later is no longer able to be relied upon, to the person's detriment Can be difficult to distinguish between representations of fact and promises E.g. "I have no property rights in this area" vs. "I promise not to assert my property rights in this area" Makes sense to extend estoppel doctrine to promises as well, but initially had to fit a case into one of the 4 traditional reliance categories (supra) R1 included §90 which did not purport to restrict promissory estoppel to the 4 traditional categories; one of the rare cases R of K was not a restatement and rather an impetus for change Requirements, see §90 A promise that Promisor should reasonably expect to induce reliance (action or forbearance) of a character that is: Definite (a particular type of action or forbearance) AND Substantial (not insignificant action or forbearance) Which does induce such reliance (action or forbearance) Inducement standards for BFE from §81 do not apply here More of a but-for standard If the promise had not been made, what would the promisee have done? But for the promise…. Whether the promise induced reliance is an issue of fact Is binding if injustice can be avoided only be enforcement of the promise R2 omits "definite and substantial" but still implied to be required Speaks to the evidentiary and cautionary concerns Promisee is compensated for injury caused by reliance Thus the damages awarded are typically reliance damages If not trying to encourage reliance on the promise, we give reliance damages But the formulation implies that we have to give expectation damages Which is why some object to the term "promissory estoppel," which R does refrain from using Because what is being estopped is the defense that there is no consideration In effect, this treats the promise as though it had valid consideration And since the promise has valid consideration, the promise should be enforced and the promisee should be entitled to expectation damages (but generally they are not) Court may use discretion in deciding type and amount of damages Rule of thumb for deciding reliance vs. expectation Prefer the easier one to calculate (reliance vs. expectation) Malice or bad faith on part of promisor, prefer expectation Strong case, prefer expectation; weaker case, prefer reliance If there is a large disparity between expectation amount and reliance amount: Don't want to encourage reliance on promissory estoppel, so prefer compensatory amount Prefer reliance if expectation is much higher If reliance exceeds expectation, prefer expectation Restitution (cause of action) o Recover for benefit conferred that would be unjust for the receiving party to retain NOT a basis to enforce a promise, just to compensation from unjust enrichment o Background Debt - touchstone was not the promise to repay the debt but the promisor's receipt of something of value from promisee Promisor should not be able to keep the thing of value without compensating promisee Looking at the benefit to the promisor o Different senses of "restitution" Restitutionary measure of damages Restitution as a theory of recovery (claim of action) Restitution damages are not the same as a restitution claim of action But damages in a restitution claim will use the restitutionary measure o Theory is of "quasi contract" or K implied by law, AKA recovery in quantum meruit Class of obligations which are imposed or created by law without regard to the assent of the party bound, on the ground that they are dictated by reason and justice Legal fiction; not a true K, but clothed in the construct of a contract for the purposes of remedy Bound not by consent but by equity o Key elements are "enrich" and "unjustly" D in fact received a benefit And retention of that benefit without payment in return would be unjust o Factors for determining if keeping the benefit (without compensation) would be unjust Reasonable opportunity to decline benefit? Excuse for not offering contract? Not for officious intermeddler Emergency - encourage assistance No restitution for nonprofessional rescuers They render the service gratuitously, without expectation of compensation Presumption that the service is being done as a gift You can't make a gift and then change your mind and seek restitution No restitution for gifts Opposite presumption for professionals, because they don't generally give away their services for free Even if there was an opportunity to bargain (e.g. an injured person needing a ride to the hospital), most ppl would not engage in such bargaining Restitution damages to doctor If the person died, the services didn't end up enriching the beneficiary So cost avoided makes more sense than net enrichment If the person lived, the net enrichment is still hard to quantify Hard to put an accurate dollar figure on a person's life o Cannot seek restitution from 3rd party who happened to receive the benefit, because that party was not involved in the promise No restitution from 3rd party for performance under a K E.g. Callano shrubbery case Exception If plaintiff has exhausted all remedies under the K and still not made whole, can seek restitution from a 3rd party Basically a constructive guarantee assumed upon the 3rd party NOT followed in most jurisdictions (distinctly minority approach) E.g. Paschall bathroom construction case Person who contracted the construction went bankrupt and builder could not collect, so sought restitution from the homeowner who was enriched by the bathroom But if the homeowner had loaned the person money to have the bathroom built, no restitution bc they were not enriched If the person who had the person built gave it to the homeowner as a gift, no restitution, because we don't make people pay for gifts Builder could've gotten a guarantee from the homeowner but didn't, so why should we enforce a constructive guarantee? They chose not to negotiate with the homeowner even though they could have Indeed this is why most courts would not give restitution in this case See also, mechanic's liens statutes o Services in family context Must overcome legal presumption that the services were performed gratuitously Presumed unless circumstances are extraordinary Remedy (enforcement of a promise) o In choosing between the approaches (below), the normal goal is to protect the expectation interests of the promisee Give that party the full benefit of the bargain by putting him in the same position he would've been in had the K been fully performed Encourage ppl to rely on Ks, especially in the context of commercial Ks Expectation recovery encourages reliance better than reliance recovery does For some kinds of Ks, especially non-commercial, we're less concerned with reliance on the promise and more concerned with compensating an injured party (e.g. perhaps in the case of cosmetic surgery) §351(3) a court may limit damages for foreseeable loss by excluding recovery for loss of profits by allowing recovery only for loss incurred in reliance or otherwise, if the court concludes that under the circumstances, justice so requires in order to avoid disproportionate compensation Expectation damages are usually higher than reliance damages, except when the K as fully performed would have been a losing K In this case, the plaintiff shouldn't be awarded reliance damages because it would overcompensate them But the plaintiff can opt for reliance damages unless the D (breaching party) can prove that plaintiff would have lost money on the K (i.e. that they would have had a negative profit), see §349 o o But this involves uncertainty in terms of calculating how much the cost of full performance would have been, and showing such loss must be to a reasonable degree of certainty Burden is on D because they breached, and we wouldn't even be calculating damages if not for that §373(1) upon material breach, the injured party may cease further performance and is entitled to restitution for benefit conferred on the breaching party in the way of part performance or reliance Majority approach, but some courts bar restitution when it exceeds expectation damages (see restitution section below) See also full performance exception below Types of relief Specific relief / specific performance Not normally awarded; this is the exception It's rare that you can convince the court that there is no adequate alternative to the specific performance connected to the promise Reserved for special cases where monetary relief is considered inadequate, e.g.: K for sale of land Non-compete covenant (essentially a negative injunction: stop doing something) Release promise (promise not to sue) May be enforced by dismissing the lawsuit The examples above don't entwine the court in messy performance issues, i.e. they don't have to get in the middle of forcing a party to do an affirmative performance (noncompete is negative performance) Substitutionary relief Money damages as a substitute for actual performance Remedies seek to protect three different alternative interests of promisee (summarized in §344) Expectation Interest Goal Give party the benefit of the bargain, ergo AKA "benefit of the bargain" damages Put the promisee in as good of a position as he would have been if the K was fully performed Plaintiff is entitled to receive the value to them of the loss (e.g. home movies destroyed, award of ~$30k) Usually the remedy given for breach Just like why we use BFE to enforce promises rather than the reliance rule: it does a better job of encouraging reliance on promises than reliance damages Much more likely to implicitly rely on the promise if expected full amount of promise would be guaranteed Measuring expectation interest in awarding money damages, see §347 Generally the most generous measure of recovery Promisee typically has a right to receive expectation damages When expectation damages equate to a negative number, there are no expectation damages Components [+] Loss in Value (to injured party) Difference between what was promised and what was received [=] Value Promised [-] Value Received Value Promised should be measured at the time the promise is to be performed Which matters in the case of fluctuating prices from creation of K [-] Cost Avoided Cost avoided by not having to perform under the K Upon a material breach, the non-breaching party is released from the obligation to perform any further Excuses the injured party from any further performance Can immediately cease performance, treat it as a total breach, terminate the K, and immediately sue for breach When the injured party ceases performance, they save whatever cost would have been expended by continued performance Without factoring in this component, the injured party would receive more value than if the K had been fully performed; therefore this value must be deducted [=] cost of fully performance [-] cost of reliance Cost of reliance is the cost of what has already been performed by relying on the K [+] Other Loss Consequential or incidental loss E.g. additional cost to procure substitute performance, failure to perform causes the party to lose money on other Ks, or lose/breach other Ks There are limits on these indirect damages, i.e. emotional disturbance (see below) Recovery for emotional disturbance will be excluded, see §353, except where: There is also bodily harm OR K or breach is of the kind that serious emotional disturbance is a particularly likely result Type of K E.g. Ks dealing with dead bodies, messages pertaining to death Nature of the breach Breach in conjunction with conduct that is particularly likely to cause serious emotional disturbance E.g. kicking out everyone from an event space using foul language Emotional disturbance limitation is essentially a specific application of the foreseeability of loss limitation [-] Loss Avoided The result of the injured party minimizing adverse consequences of breach E.g. materials purchased for a project which can be reused for another project Alternative means to formulate / conceptualize (formula B) [=] Expected Profit [+] Cost of Reliance [-] Value Received [+] Other Loss [-] Loss Avoided [=] Expected Profit [+] Reliance Damages Reliance Interest Compensation for lost caused by reliance on the K Detriment to the promisee Restore the promisee to the position they would have been in had the K never been made o Have to think about the counterfactual of what plaintiff would have done had they not entered into this particular K (e.g. would they have merely entered into the same K with another?) [=] Cost of Reliance [-] Value Received [+] Other Loss [-] Loss Avoided As shown above, this is Expectation Damages less Expected Profit, and a plaintiff may elect to waive Expectation Damages in favor of Reliance Damages when the Expected Profit under a fully performed K is hard to prove E.g. the case of the botched nose job Reliance damages only plays a role when Expectation Damages just don't work for one reason or another, e.g.: Too hard to calculate Non-commercial kind of K where we don’t think profit makes sense in the first place Expectation damages are way too disproportionate to the K prices Plaintiff cannot recover reliance damages if D can prove (to a reasonable degree of certainty) that they would exceed expectation damages Restitution Interest, see §373(1) Compensating for any benefit conferred on the breaching party, the promisor Put the breaching promisor back in the position he would have been in had the K never been made, by taking away any benefit conferred Courts will still award the benefit conferred, even if the conferred benefit is no longer of any value to the breaching party (e.g. part performance of an abandoned construction project) Measurement Measuring benefit conferred Cost Avoided, see §371(a) Cost to acquire the benefit from someone similarly situated Not determined by the K price but the fair market value Net Enrichment Wealth or other welfare interests increased With either method, the value received by the injured party (i.e. value conferred by the breaching party) should be subtracted from the benefit conferred [=] Benefit Conferred [-] Value Received (by injured party) Which to choose? Choose the easier one: if one is relatively difficult or impossible to estimate/calculate/conceptualize, use the other one Choose smaller one Some courts would say that you cannot recover restitution damages if they would exceed expectation damages Except where the plaintiff is merely seeking the return of a definite sum of money already paid to the breaching party (in this case all courts would award restitution) But most courts follow R2 approach where injured party is always entitled to restitution No right to restitution if the injured party has performed all duties under the K and no performance by the other party remains other than payment of a definite sum of money for that full performance of the K, see §373(2) In this instance the calculations (and uncertainties involved in estimating values) can be fully avoided because the expectation measure is very simple: the payment required by the K Basically a rule of convenience/simplicity Many courts will limit restitution recovery to the K price, i.e. cap any restitution damages at the amount of the breaching party would've had to pay under the fully performed K General limitations on damages These limitations can affect other types of remedies (e.g. promissory estoppel) as well as alternative methods of measuring damages (e.g. reliance) Avoidability of Loss Damages are not recoverable for loss that the injured party could have avoided without undue risk, burden, or humiliation, see §350(1) Whether you acted reasonably in attempted to avoid unnecessary loss Typically turns on factual issues that would warrant a trial When it becomes clear that the other party is in breach or will not perform under the K, the nonbreaching party must take reasonable steps to minimize loss incurred by breach AKA "duty to mitigate damages" But misleading, because failure to perform duty does not come attached with legal liability; consequence is that you cannot recover for any losses that could have reasonably been avoided through mitigated When you do take reasonable steps to mitigate loss, any additional cost incurred in doing so may be recoverable as Other Loss Policy underlying the principle is to encourage parties to minimize adverse consequences of breach With the dead horse case, the P could have recovered the cost of boarding the horses as a means of mitigating damages; even though he did not do that, could he recover the cost that he would have incurred by boarding the horses to partly compensate for his loss caused by the breach? As noted by the UCC, even if a buyer repudiates the sale of goods, the seller may be able to (or expected to) continue manufacture of the goods Completed goods sold to another buyer may recoup more value than partially completed goods sold for scrap Therefore completion of the goods may be the expected route for the seller to take to best mitigate damages However, we will not reduce the seller's damage award as long as it was reasonable, at the time of breach, to take that course of action Injured party is not precluded from recovery under the avoidability principle, provided they made reasonable but unsuccessful efforts to avoid loss, see §350(2) Substitute contract Governing standard according to R2 is whether the injured party acted reasonably in refusing a substitute K in light of any undo risk, burden, or humiliation Differences from a financial standpoint are reasonable for the plaintiff to be expected to take on, because those can easily be compensated in a breach action Substantive differences re: undo risk, burden, or humiliation a plaintiff may not be expected to take on Conditional substitute K, conditioned on waiving right to breach claim makes the substitute K unduly risky/burdensome as a matter of law for most all courts Lost Volume If the breach means the injured party's volume of business is going to be smaller than if the K hadn't been breached, that loss is recoverable But if the total volume even after the breach is the same, i.e. the business is essentially operating at full capacity, then the later K which brings the volume up to the same level as it would have been w/o breach is considered a substitute The burden of proof w/r/t mitigation is on D If breaching party wants to prevent injured party from recovering their actual loss suffered by saying the party could have avoided some particular loss, it's the breaching party that has to prove that the injured party could have in fact avoided that loss w/o undo risk, burden, or humiliation Can you contract away avoidability requirement? Maybe, unless results in unreasonably high penalty Better to include K recitals that explain why certain types of mitigation strategies or other Ks may not be feasible Foreseeability of Loss, see §351 Damages are not recoverable for losses the breaching party did not have reason to foresee as a probably result of the breach *when the K was made* Universally accepted limitation "other loss" caused by breach includes "consequential loss" that is more remote but due to the breach "incidental loss" that is closely tied to the breach itself E.g. cost to mitigate, cost to find substitute Only consequences that were likely or probably when the K was made Loss is foreseeable when: It follows in the ordinary course of events This loss ordinarily follows from this breach of this type of K Usually picks up the loss in value from the K May also pick up certain other types of loss, e.g. the cost of going out and finding someone else to perform These are the "incidental losses" Loss is probable (not just possible) It follows as a result of special circumstances beyond the ordinary course of events that the breaching party had reason to know about Will occasionally apply to limit plaintiff's full loss in value, e.g. plaintiff attaches unique value to other party's performance, foreseeability might limit amount recoverable But by and large typically serves to limit what would fall into "other loss" Loss is probable (not just possible) Foreseeability is based off the information known to the breaching party at the making of the K Because additional details of probably consequences could factor into the K price or even the other party's decision to enter into it in the first place Unfair to expose a party to damage risks for something they had no knowledge (or reason to know) about when entering into the K Foreseeability is not based on the foreseeability of breach or a certain reason for breach but solely foreseeability of loss given that breach You can put the other party on notice about what types of loss may result from breach Special circumstances They become foreseeability Certainty of Loss Damages are not recoverable for loss beyond the amount the evidence permits to be established with reasonable certainty, see §352 Can only recover for those losses for which you can present evidence establishing the dollar amount of the loss with reasonable certainty If difficult to prove, plaintiff is allowed to show the amount of loss based on the methods set out in §348(2), i.e. diminution of FMV or cost to remedy/finish performance But these measures are still subject to the certainty requirement Reasonable certainty Does not require absolute mathematical precision; approximations are permissible Only requires whatever level of accuracy and definiteness the facts will permit Merely looking for a reasonable basis to estimate the dollar amount of loss Doubts about certainty of an estimate are usually resolved against the breaching party Especially if the breach was willful rather than inadvertent Because the alternative is that the plaintiff cannot recover for that loss at all Applies to any of the various damage components Applies with special force to attempts to prove the dollar amount of other loss Especially consequential damages E.g. can be hard to prove the profits that would have been made from a lost business opportunity resulting from a breach Often framed in terms of calculating or predicting loss as a dollar amount, but it also has a causation element embedded Have to establish that these are losses that would have occurred In terms of injury to professional reputation, courts often conclude that damages are too speculative to award Too many factors into how things play out But with enough creativity and diligence, the certainty limitation is surmountable, there just needs to be sufficient evidentiary basis for which the jury can conclude that but for the breach, these particular opportunities would have presented themselves Loss of goodwill for a business is similar to injury to professional reputation for an individual Rather than being completely barred, recovery can be discounted by chance of obtaining that value if not for the breach, see §348(3) More modern approach; traditional approach was no recovery for value that more than likely would not have been received, e.g. going on a gameshow with only a 2% chance to win $50k So breaching party does not get off scot-free Lost business opportunities Old approach was essentially a per se ban on recovery for new businesses, bc amount of loss would be just too speculative as a new business with nothing to compare to (but allowed recovery for established businesses which had data to support an estimate) Modern approach is to allow expert testimony to help support an estimate of lost business for new businesses, e.g. by looking at earnings once the business does open or looking at similarly situated businesses Factfinder sorts out from competing testimony, business models, etc. presented by both parties at trial In general, courts have become a lot more comfortable accepting statistical evidence to establish amount of other loss Courts may be reluctant to accept the certainty of lost royalties for a book, record, etc. bc of the many factors that affect appeal and sales, but the modern trend is allow both parties to submit evidence and expert witnesses to try to show what this figure would be Certainty is a question of law: whether the plaintiff has provided enough evidence for the question to go to a jury Liquidated Damages The extent to which the parties upfront as a part of their contractual promises also promise what they are going to pay as damages should they breach Principles of freedom of K say that if the parties agree to it then we should enforce it A good way to ensure you will be compensated for a loss that is likely to occur with a breach but whose amount would be difficult to prove is to specify the amount up front how much the breaching party would have to pay in damages Advantages Ensures that the injured party will be compensated Saves the parties and the court the difficult wrangling of estimating loss o o However, if the liquidated damages amount is set too high and overcompensates the injured party, that looks like punitive damages which punish and deter breach, which are not appropriate goals of K law Liquidated damages vs. alternative performance obligation? E.g. uphold the lease or pay a sum to cancel a lease: could be construed as either Would allow avoiding the enforceability limitation of liquidated damages provisions Principles of enforceability of liquidated damages provisions, see §356(1) Damages for breach by either party may be liquidated in the agreement but only an amount that is reasonable in light of the anticipated or actual loss caused by the breach and in light of the difficulty of proof of the dollar amount Anticipated loss Actual loss Difficulty of proof A term fixing unreasonably large damages is unenforceable on public policy grounds as a penalty If the amount is deemed unreasonably large, it is unenforceable as a penalty But the injured party can still recover under the normal damage rules As long as the amount appear reasonable and is not clearly disproportional and clearly punitive, it will likely be enforced This is an objective test due to the difficulties of proving whether the liquidated damages were meant to be punitive or not However, some courts will attach some weight to the purpose of such a provision (i.e. that it was meant to be punitive) Gross receipts formula is suspect on its face bc it doesn't directly reflect/tie-in to actual loss Shotgun/blunderbuss - fixed liquidated damages provision that applies to any kind of breach Dangerous Calling this a penalty is not controlling, but not a good idea Equitable Relief Injunction, e.g. non-compete Liquidated damages provision does not preclude equitable relief remedies May actual bolster But courts will often only grant with a proper showing that money damages are inadequate Contract recitals which help make out the case can be included Can you contract away the right to equitable relief? Probably, esp if there is liquidated damages in lieu of that Misc. o Breach Breach by anticipatory repudiation Statement or other manifestation evidencing a party's intention not to perform a K Treated as a present breach of the K even if the performance of the breaching party is not due until the future (even a long time into the future) Punitive damages are not recoverable for breach of K unless such conduct is also a tort, see §355 As long as we fully compensate the non-breaching party, the purpose of K is not to punish the breaching party Also why courts do not routinely give specific performance for breach bc it would prevent parties from breaching when it's economically sensible Breaching, in general, is not discouraged by K law Goal is not to be punitive, but if the choice is too hard to call on the merits, willfulness may be used as a "tie breaker" in favor of the non-breaching party But otherwise, willfulness should not have any independent significance in choosing the appropriate measure of damages The fact that a breach is willful does not make it a tortious breach Material breach (materiality of breach) Material breach treated as a total breach, i.e. a breach of the entire K Permits the injured party to immediately cease their obligation/performance i.e. Excuses the injured party from any further performance under the K Breaching party is typically entitled to a restitution cause of action But unlike the liberal use of cost avoided when measuring damages to nonbreaching party under a K claim of action, courts will typically use a net enrichment approach and also limit to overall K price Must also deduct any loss incurred by the injured party on account of the breach E.g. in pipe / house building case, net enrichment would be measured by the FMV of the house, capped at the K price In this case it may make little difference whether the breach is characterized as material or minor, because either the homeowner pays the K price (less loss due to breach) or pays the FMV price (less loss due to the breach), which may be roughly the same if the type of pipe used is not inferior to that specified in the K Non-material = trivial/innocent breach (in the words of Cardozo) = minor breach If the breach is minor/non-material, the breaching party has substantially performed, and the nonbreaching party is not excused from further performance But a breach is still a breach Injured party still has right to damages from minor breaches I.e. if the breach is non-material and further performance is not excused, it is still offset by any losses caused by the breach Materiality ONLY tells us whether the nonbreaching party is excused from further performance under the K Including performance in the way of monetary payments (in whole or in part) Materiality of the breach has NOTHING to do with measuring the loss in value caused by the breach, i.e. loss due to breach is measured exactly the same whether the breach was material or not When nonbreaching party has fully performed, materiality is out of the picture / completely irrelevant (since only relevance is whether nonbreaching party is excused from further performance) Materiality ONLY comes into play w/r/t to constructive/implied conditions of exchange No hard and fast formula for determining whether a breach is material Factors of determining materiality, see §241 Trivial vs. significant (extent of breach) I.e. extent of breach compared to entire contractual undertaking of breaching party Did the injured party still get essentially what they were bargaining for? (e.g. the brand of pipe case) i.e. the performance was "good enough" and a damages remedy is sufficient to compensate for the breach? Or has the breach been so significant that the injured party was essentially deprived of what they were bargaining for? Is just a damages remedy enough to make them whole? Damages are good enough to compensate? Possibility of forfeiture? E.g. a permanent structure on land vs. an RV which could simply be returned i.e. if the breaching party must forfeit what they had already performed, we are less likely to say that there was a material breach Innocent/unintentional vs. willful Likelihood that breaching party with cure the breach i.e. when cure is possible, less likely to call it a material breach o o Conditions A condition is an event that must occur before an obligation to perform arises You can condition your obligation to perform Failure to fully perform as promised is always a breach and always gives rise to an action for breach, even if minor/non-material breach And in the case of conditional performance obligations, the breach may also excuse the injured party from further performance (always with express, only material breaches with implied) (1) Extrinsic/incidental conditions Can be express or implied Failure to meet the condition does not give rise to an action for breach (2) Bargained-for performance obligation Failure to perform would give rise to an action for breach (a) Express condition (misleading, bc other types of conditions can be express) Strict compliance required for conditional performance obligation to arise, i.e. failure to perform in accordance with the condition means the condition performance obligation never arises Given the consequences of express conditions, courts require clear and unambiguous language before they will say there is an express condition The lesson is, with drafting Ks, if you want to condition performance on express conditions, it must be said very clearly and should be said several times e.g. buyer has no obligation to pay at all unless and until there is strict compliance with all specifications, and even minor/insignificant deviations will excuse the owner from paying anything Courts is unlikely to interpret this way unless said this way, i.e. even minor deviations excuse performance With an express condition, breaching party has no right to a restitution recovery Therefore, express conditions are "doubly harsh" and why courts are very particular about interpreting conditions as express (b) Constructive (implied) conditions of exchange Where one performance comes before another, it is an implied condition of the later performance Substantial performance / material breach ONLY apply to constructive/implied conditions of exchange Typically a restitution cause of action even if no K cause of action for breaching party, if nonbreaching party would be unjustly enriched by breaching party's performance and being excused from their performance under the K Courts usually liberal in awarding damages to nonbreaching party under K cause of action with cost avoided approach of restitution measure than with this type of restitution, which courts will typically limit to net enrichment approach and limit to the K price §348(2), If a breach results in unfinished or defective construction, and the loss to the injured party is not proved with sufficient certainty, the injured party may recover based on either: This is a measure of loss in value (a) Diminution in market value due to breach But if that amount is greater than the cost to remedy or complete, the mitigation principle may cap the loss in value figure OR (b) The reasonable cost to completing performance or remedying the defects, if that cost is not clearly disproportionate to the probable loss in value to the injured party A good heuristic is often to ask, if the injured party was awarded that amount of money, would they likely use it to remedy the defective performance? Economic waste is not really relevant, the question is whether the injured party would be overcompensated Exam o o o o o o o o o Legal analysis under current state of law Policy may help if it's a close call, but only if advances legal analysis Evidentiary Cautionary Focus on facts given Except if necessary to decide issues within those necessarily raised Use IRAC More important to cite to UCC Don't need to cite to R2 sections or cases Reciting a long R2 section verbatim can be counterproductive But citing can be shorthand way of demonstrating you recognized an issue Points for spotting and framing issue, stating rule, analysis, maybe some for conclusion